Cervical spine

Analysis: the checklists

Injuries are most often missed because of poor radiographic technique and/or inaccurate film interpretation1,2,4–6. Most errors are avoidable5. Missed C-spine abnormalities occur most commonly at the top or at the bottom of the C-spine1,2.

□ Whatever the level of violence, C-spine injuries frequently occur at the C1–C2 level1,3,4,6.

□ The most common fracture in elderly patients following a fall is a high cervical injury1,3.

□ Between 9% and 26% of patients with one fracture or dislocation of the spine will have further fractures demonstrable radiographically at other levels5.

□ If you have detected one injury you must still complete the checklists, in order to find any additional abnormalities.

Priority 1: Lateral view checklist

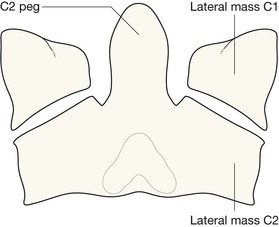

Identify the odontoid peg and assess its position and anatomical relationship to the C1 vertebra. Overlapping structures (eg mastoid, ear lobes, C1 vertebra) can make this difficult. Questions 1–5 will help you to overcome this.

Ask yourself ten important questions:

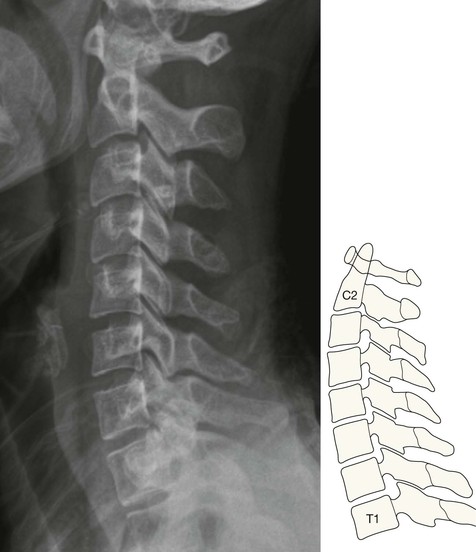

1. Is the radiograph technically adequate? Ensure that the C1–C2 articulation and the superior surface of the T1 vertebra are clearly seen.

2. Have I identified the anterior arch of the C1 vertebra (the “coffee bean”)?

3. Is the anterior cortex of the odontoid peg (the Peg) closely apposed to the “coffee bean”?

4. Is the line of the anterior cortex of the Peg continuous with the anterior cortex of the body of C2? Any displacement implies a Peg fracture or fracture of C2 body.

5. Is the line of the posterior cortex of the Peg continuous with the posterior cortex of the body of C2? Any displacement or break indicates a Peg fracture.

6. Is Harris' ring7 normal? A break in either the anterior or posterior margin of the ring indicates the high probability of a fracture of the Peg/body of C2 (p. 176).

7. Are the posterior arches of C1 and C2 intact?

8. Are the other vertebrae (C3–C7) intact (p. 192)?

Priority 2: AP Peg view checklist

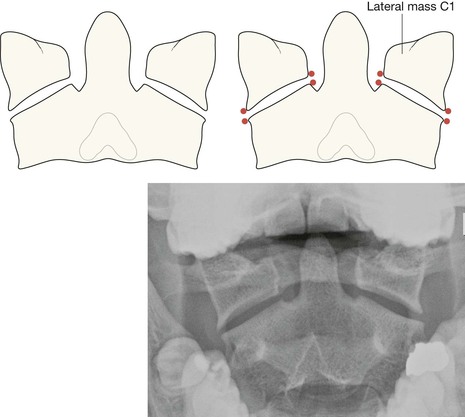

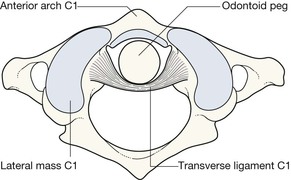

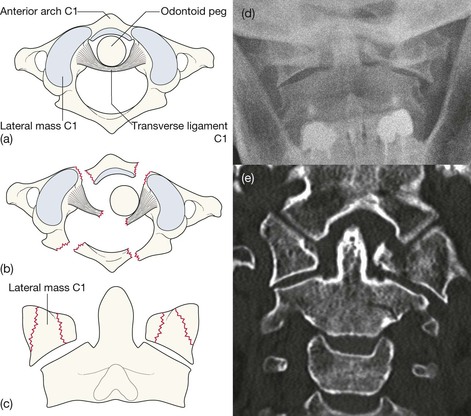

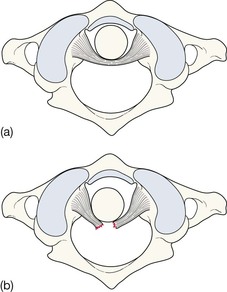

The anatomical arrangement of the C1–C2 articulation allows extensive neck rotation whilst providing maximum stability. This stability depends on the integrity of the ligaments, particularly the C2 transverse ligament. Various other ligaments enable C1 vertebra to be held in the optimal position above the body of C2 vertebra. Any deviation from this alignment indicates either ligamentous disruption or a broken vertebra.

Ask yourself three important questions:

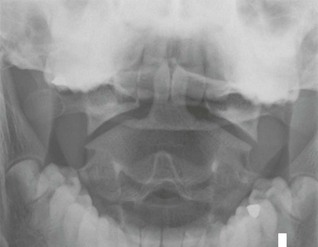

1. Do the lateral margins of C1 align vertically with the adjacent lateral margins of C2?

2. Are the spaces on each side of the Peg approximately equal?

Priority 3: Long AP view checklist

The lateral and Peg views are the most useful images. The diagnostic return from the long AP view, in terms of abnormalities detected, will be considerably less. In addition, it is easy for the unwary to read too much into the AP view.

Ask yourself two questions:

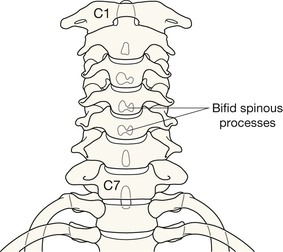

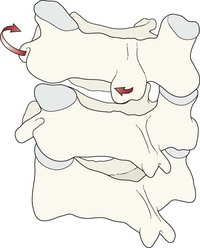

1. Are the spinous processes in a straight line?

If not, consider unilateral facet joint dislocation (see p. 194).

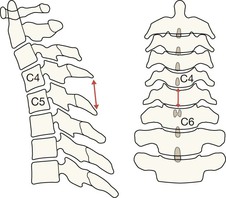

2. Is the space between adjacent spinous processes approximately equal?

A warning: if a space is more than 50% wider than the space immediately above or below, this is highly suggestive of an anterior cervical dislocation16. In practice this observation is most useful in the severely injured patient whose shoulders have obscured some of the vertebrae on the lateral radiograph17. It can provide an important warning that the neck must be managed very carefully until a lateral view or CT has accurately defined the alignment of the vertebrae.

The common injuries

Injuries at C1

Fractures C3–C7

Including spinous process fracture, vertebral body compression fracture, and hyperflexion teardrop fracture.

The cardinal rule: The lateral radiograph must always, always, include a well visualised superior surface of the T1 vertebra. Many errors1,3,5 occur because the top of T1 has not been included on the radiograph. Check the lateral view as described on p. 174.

Pitfalls

On the AP Peg view

▪ An unequal space on each side of the Peg is commonly due to patient positioning with the neck slightly rotated. All the same, such a finding necessitates very careful inspection of the alignment of the lateral masses (see p. 180).

▪ A black line across the Peg might be a Mach effect or tooth artefact (p. 183) rather than a fracture. Evaluation of the lateral view is then the important next step.

Spasm related—delayed instability

Following trauma, severe pain and spasm may make it difficult to exclude a significant injury to the posterior ligament complex. Muscle spasm can hold the neck in an anatomical position and mask ligamentous rupture. Instability may only become evident after a few days when the spasm has reduced.

It is therefore important that any patient with severe pain and spasm who appears fit for discharge and is put in a collar should be asked to attend again in a few days for further evaluation. Lateral views in flexion and extension might form part of that evaluation. These additional radiographs must be taken under close clinical supervision. If they remain at all equivocal, an MRI examination should be obtained in order to exclude a ligamentous injury.

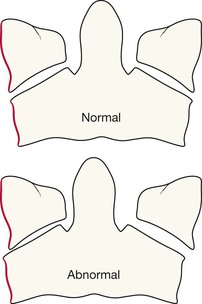

Age related changes

Age related degenerative changes are very common over the age of 40. Distinguishing between changes due to cervical spondylosis and those resulting from an acute injury is not always easy.

The age related appearances shown below are frequently present in the middle-aged and the elderly.