Robert Thorne was an early enthusiast for English exploration to the north. His portrait is owned by Bristol Grammar School, which he founded after his return to England.

English trade in the first half of the sixteenth century was dominated by wealthy foreign merchants such as George Gisze, shown here in a portrait by Holbein.

As a young man, the great polymath John Dee was an expert adviser to the organisers and leaders of the 1553 expedition.

Seville was awarded exclusive rights to trade with the New World. It was here that Sebastian Cabot lived and worked for much of his career before he returned to England.

Sebastian Cabot, the brilliant, enigmatic and divisive navigator, was the driving force behind the 1553 expedition.

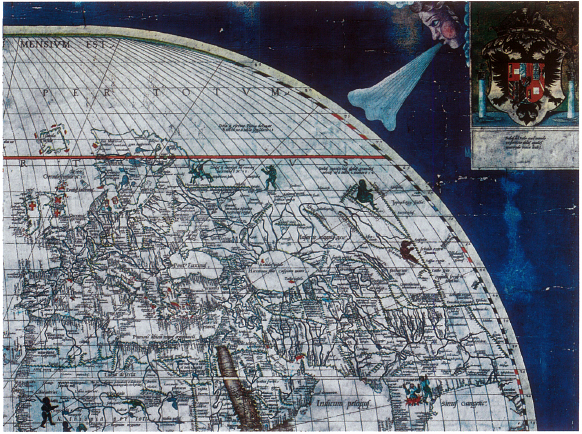

Cabot worked on this map in 1544 before republishing it in England. The north-eastern corner shown here refers to Indians allegedly shipwrecked above Asia in classical times: proof to some of the existence of a north-eastern passage.

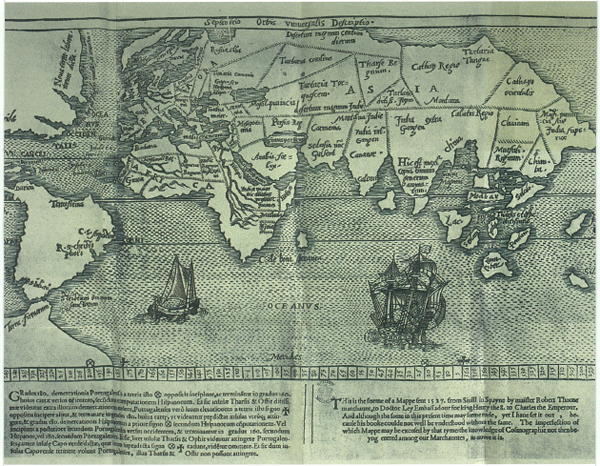

This map, which was attached to Robert Thorne’s letter advocating a northern discovery, shows both the passage he believed to exist directly over the Pole, and the limits of European knowledge.

For navigators like Richard Chancellor, the sighting of astronomical objects offered the key to pinpointing a location on the earth’s surface. Here an astrolabe is used to measure the altitude of the sun at midday while a cross-staff is used to sight the Pole Star.

This world map was made by a French cartographer for Henry VIII. The empty spaces along the north of Asia reveal the lack of knowledge about this part of the globe.

Sir Hugh Willoughby was a fearless gentleman soldier who volunreered to lead the I 553 expedition, despite limited navigational knowledge or experience.

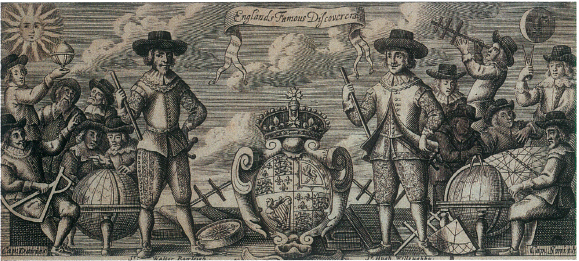

This late sixteenth-cenrury engraving showing ‘England’s Famous Discoverers’ features Willoughby alongside other explorers made famous by Richard Hakluyt’s histories.

The Lartique was a naval ship, comparable in size to the ships of I 553, but much more heavily manned and gunned.

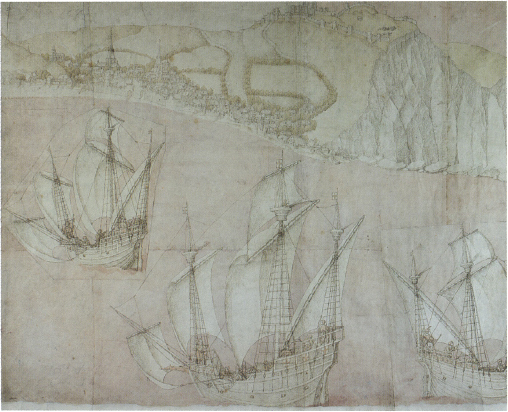

Ships off Dover, by John Thompson. Early sixteenth-century English ships, as seen here, rose high above the waterline in a manner that was better suited to conflict in European waters than to long-distance navigation.

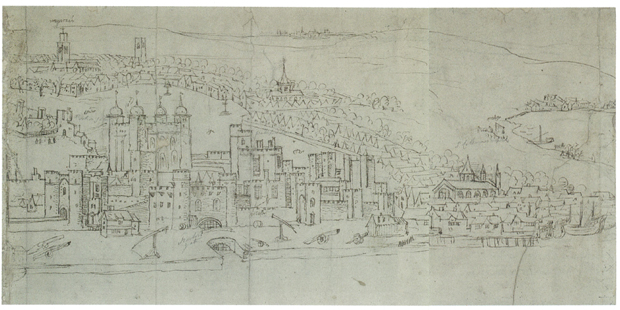

In these contemporary illustrations of London, the small shipbuilding community of Ratcliffe, from which the expedition departed, can be seen downstream of the Tower (left), as can the old Greenwich Palace, further downstream on the south bank. It was from here that Edward VI’s court watched the ships sail past (below) in May 1553.

William Borough sailed under Chancellor as a teenager and returned to this northern region repeatedly. He carefully mapped the northern coasts he knew, and marked the river where Willoughby’s ship was found.

One of the earliest maps of the Scandinavian peninsula, the Carta Marina shows many of the dangers, real and imagined, which Willoughby, Chancellor and their crews would face.

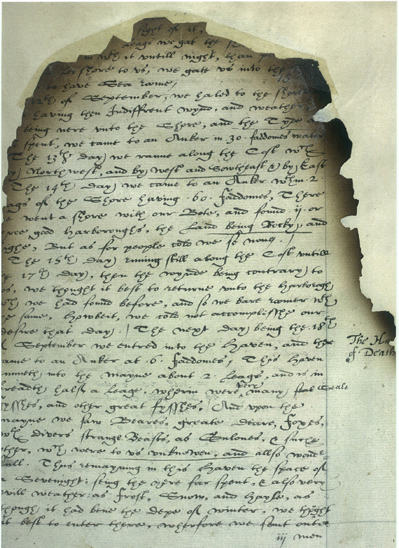

This final page of Willoughby’s log has, still just legible in the margin, the phrase ‘Haven of Death’.

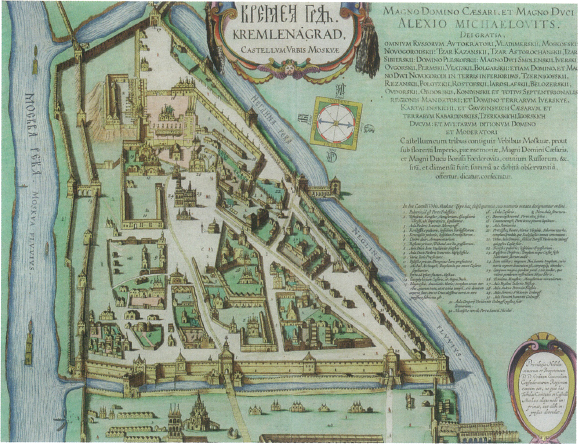

Chancellor and leading merchants paid a visit to Ivan IV (known as ‘the Terrible’) in the Moscow Kremlin in late 1553 and early 1554. The Englishmen were impressed by the clothing of individuals but not by the buildings.

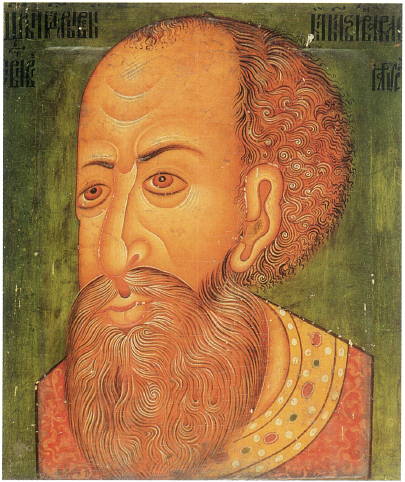

Ivan the Terrible, seen in an icon from about 1600 portrayed as an older man than when he was visited by Richard Chancellor, after his decline into bloodthirsty madness.

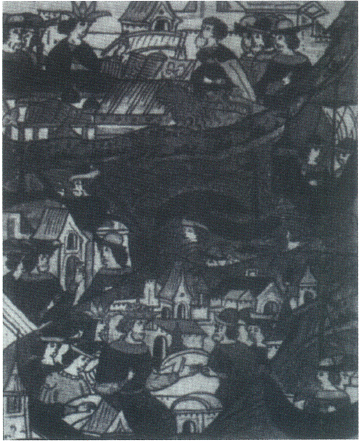

An illustration from a Russian chronicle shows (from top to bottom) Ivan bidding farewell to Chancellor and Napea, their shipwreck, and Napea greeting the King and Queen of England, Philip and Mary.

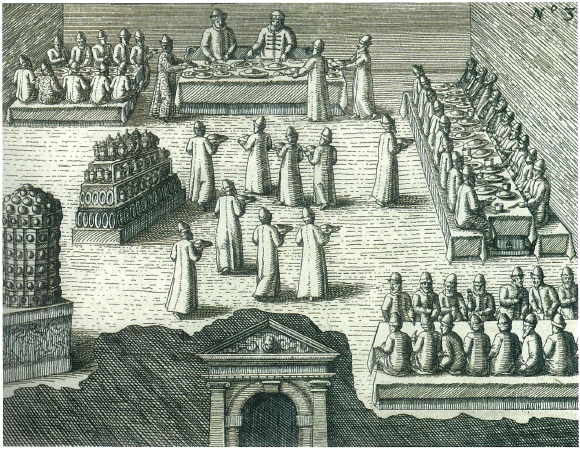

Foreign ambassadors being received at the court of Ivan the Terrible in 1578. Like the English before them, they were treated to dinner and (many) drinks at the Kremlin.

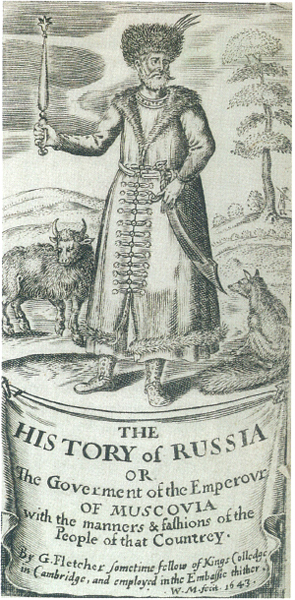

Giles Fletcher was a vicar’s son and MP who travelled to Moscow in the late 1580s to meet a later Tsar. His History of Russia was the best study yet made of government and customs in Russia.

A stamp or ‘seal die’ used by the Muscovy Company to fix its seal in wax to documents, and showing the date of its charter.

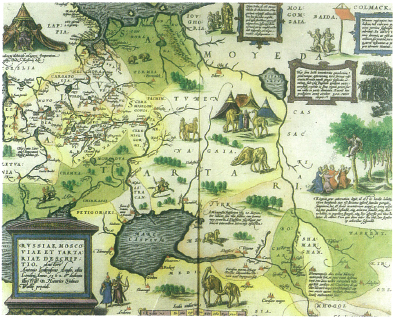

Anthony Jenkinson’s ‘Description of Russia, Muscovy and Tartary’ was printed in the first modern atlas, published by Abraham Orte1ius.