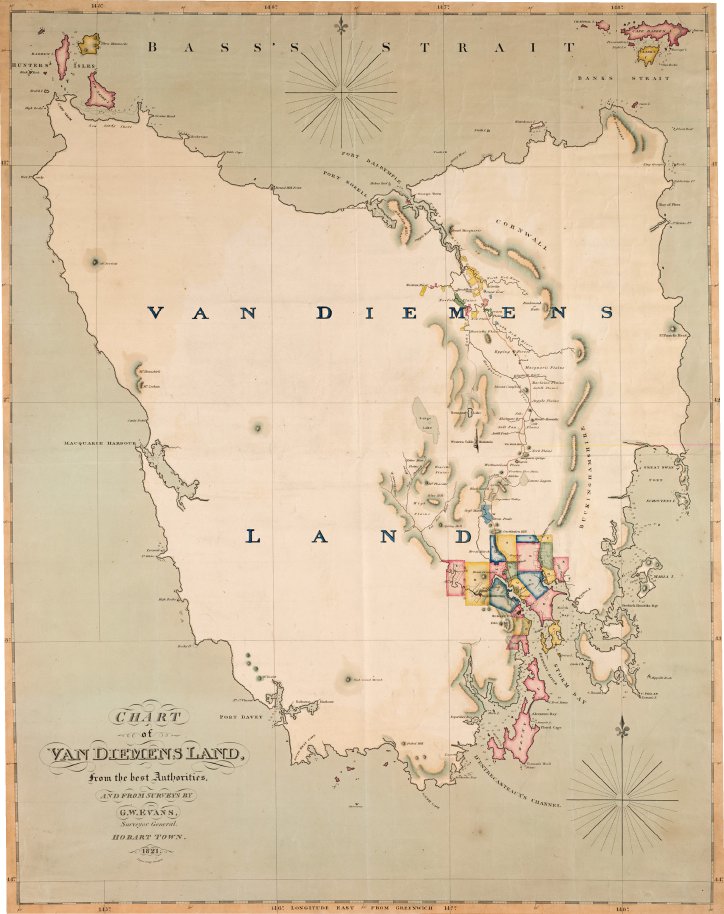

A map of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) in 1822.

There were no detailed plans for most of the Australian colonies. New South Wales began as a place to send convicts. Other parts of Australia were settled to provide somewhere for Britain to send the worst convicts. Others were started to provide a port for farmers, or to stop the French from settling on the continent. Every Australian colony had a different story.

A map of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) in 1822.

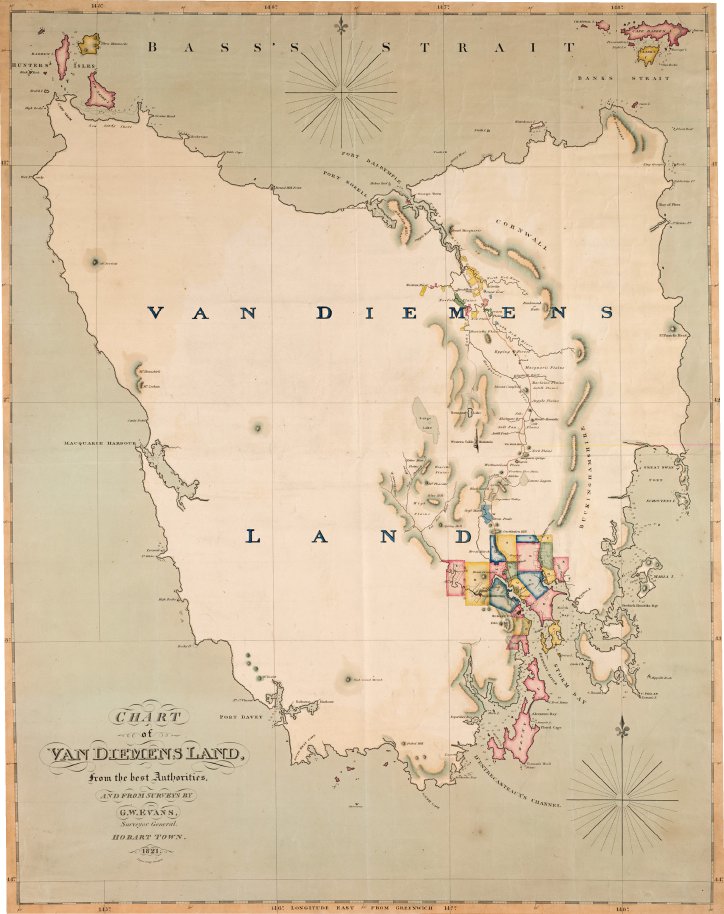

Convict John Appleby.

On 14 September 1786, The Times in London reported a plan for a colony (in what was then called New Holland) at ‘Botany Bay, on the west side of the island’.

People soon sang songs about Botany Bay, but no judge actually mentioned the place ‘Botany Bay’ in his sentencing of a prisoner until June 1791. By then, people knew that Botany Bay was actually on the eastern side of New Holland, but there was no settlement there in 1791. Nobody really cared where it was, so long as felons were being punished and sent somewhere far away from England.

The plan was for the fleet of ships to leave London in December 1786, but there were delays. On 10 January 1787, judges at the Old Bailey courthouse sentenced 15 women prisoners to be transported. Two of the women sentenced that day would become the oldest and the youngest female convicts in the First Fleet. Elizabeth Hayward was in her early teens, and Elizabeth Beckford was probably in her late 70s.

The First Fleet finally left on 13 May 1787. There were 11 ships carrying around 504 men and 192 women convicts, guarded by 212 marines, plus 136 ‘free’ people—a total of 1,044 people.

The First Fleet in Sydney Cove on 27 January 1788, painted in 1938 for Australia’s 150th birthday.

The jails of Britain were filled with deadly diseases like tuberculosis (a lung disease) and ‘jail fever’ (typhus), and so the two Elizabeths were probably fortunate to escape that fate. They both sailed on the Lady Penrhyn, which carried women convicts and their children. On that same day in January 1787, a number of other prisoners were also lucky, as their death sentences had been changed to transportation.

The journey

The First Fleet finally left on 13 May 1787. There were 11 ships carrying around 504 men and 192 women convicts, guarded by 212 marines, plus 136 ‘free’ people—a total of 1,044 people. The ships also had on board tools, equipment, tents and enough food to last for two years. It took more than eight months to reach Botany Bay, with three stops at ports along the way to take on supplies.

The 11 ships in the First Fleet included: two navy ships, Sirius and Supply; the store ships Fishburn, Golden Grove and Borrowdale; and the convict transports Alexander, Scarborough, Charlotte, Prince of Wales, Lady Penrhyn and Friendship.

The fleet called in at Tenerife in the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean to pick up missing supplies like musket balls— ammunition for their guns. The ships crossed the Equator on 14 July and reached Rio de Janeiro in Brazil on 4 August. The fleet’s commodore, Captain Arthur Phillip, who had served at one time in the Portuguese navy and spoke the language, was made welcome in Portuguese-speaking Brazil.

While in Rio, the people on board the ships were given fresh food, including vegetables and fruit. (By then, many sailors knew that fruit and vegetables prevented scurvy, a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C.) Records show that they also bought coffee, cocoa, cotton and some medicinal plants.

The First Fleet reached Cape Town in southern Africa on 13 October. There they bought figs, bamboo, sugarcane, vines, quinces, apples, pears, strawberries, oak and myrtle trees, rice, wheat, barley and corn. In addition, they purchased cattle, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, poultry and other stock for the new colony. And, once again, everyone was given fresh food.

On Christmas Day 1787, the First Fleet was sailing south of Perth. By 3 January, the fleet had passed Tasmania and turned north. Ten days later, they sailed into Botany Bay. Within a few days, on 26 January 1788 all the ships moved to Sydney Cove.

Over the next few days, the convicts who had survived the journey came ashore. Some of them, like the elderly Elizabeth Beckford, had died on the way, while a few babies had been born. Some of those who landed that day would die in Australia, but others would later return to Britain.

Many people on the First Fleet found a new and better life in what was to become Australia.

A portrait of Captain Arthur Phillip, as he appeared in 1788.

A teenage convict

Some of the convicts on the First Fleet were sent halfway across the world to the penal colony in Botany Bay for what would now be considered petty crimes such as theft. For example, teenager Elizabeth Hayward had stolen a gown, a bonnet and a cloak, with the total value of about 7 shillings. She was an apprentice who was accused of taking the items from her master, Thomas Crofts, and selling them to a pawn shop.

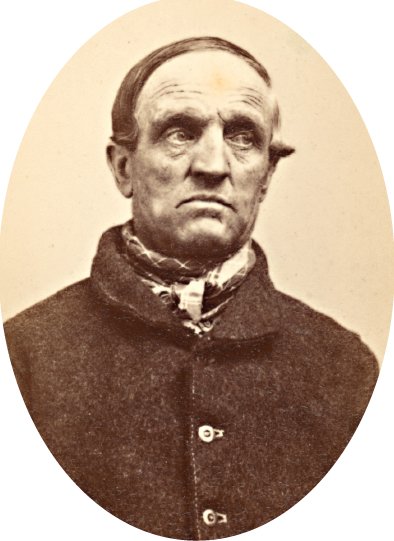

Over the next 80 years, from 1788 to 1868, some 162,000 convicts were sent to Australia. A few were innocent, a number were petty criminals who stole because they were poor and desperate, and some were real villains.

In history, there are many reasons why things happen, but often one cause may be more important than others. In the 1780s, England’s jails were overcrowded, and that was one of the main reasons for setting up a new penal colony in Botany Bay. There were several other reasons, as well.

The new country of the United States of America (USA) did not want Britain’s convicts. The courts in England were full of people who had been charged with thieving, poaching or doing something else that meant they would spend time in jail.

Portraits of convicts.

In the 1780s, England’s jails were overcrowded, and that was one of the main reasons for setting up a new penal colony in Botany Bay.

A hard life

Teenage apprentice Elizabeth Hayward stole 7 shillings worth of clothing and was sentenced to seven years in jail. The elderly woman Elizabeth Beckford got the same sentence for stealing cheese worth just 4 shillings.

At that time, there was no free education, making it hard for poor people, however clever they were, to escape poverty. Young people could be apprenticed to a tradesman at about the age of 12, but their families had to pay the master a fee called a ‘premium’.

An apprenticeship usually lasted for five years. For the first year or two, apprentices often just did menial tasks like sweeping and cleaning. They lived in their masters’ houses and were fed by their masters, but there was often very little joy in their lives.

It was even harder for older people. There was no old age pension, so an old man or woman with no family and no savings had little choice but to steal or to go into the workhouse. In such institutions, the inmates were not fed well, they were often mistreated and they were exposed to all sorts of diseases. Nobody lasted very long in a workhouse.

And so the jails were full mainly because of poverty and the very harsh laws that imposed severe sentences even for petty crimes.

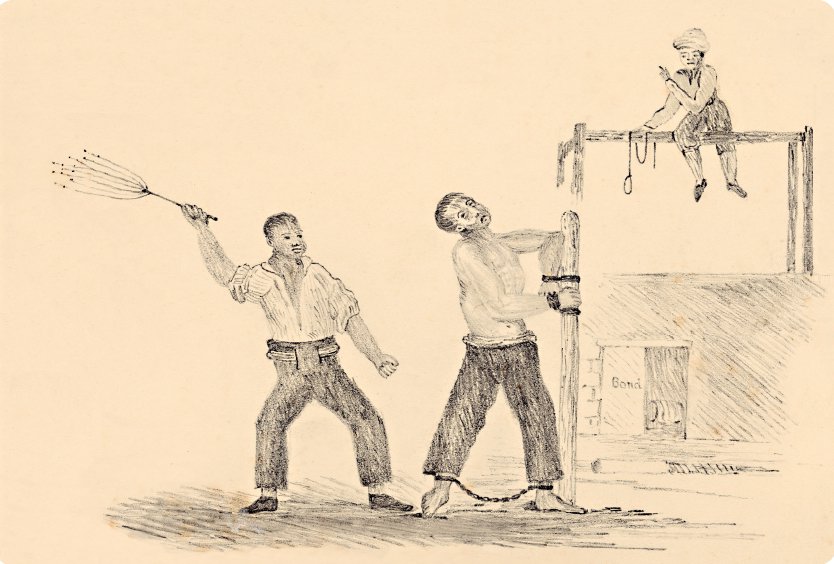

The distinctive clothing some convicts wore.

Working for freedom

As a rule, once they arrived in Australia, convicts were set to work doing useful things, especially if they had a trade. Some worked on farms, or caught fish, or built roads and bridges. Others were what were called ‘assigned servants’. They were allocated to free settlers as unpaid labourers. If they behaved well and worked hard, they could be granted their freedom.

Once their 7- or 14-year sentences expired, the convicts were then free to do as they wished. They could return to England; but, as that required a great deal of money, many of them settled in Australia.

Robert Johnston Batty showed how ‘old lags’, or convicts, could be real survivors. Born in 1796, he was orphaned at a very young age. When he was a small child in London, a gang of burglars made him crawl through windows to open the doors of the houses they were robbing. He was transported to Australia for life in 1811 when he was just 15. He was assigned to Solomon Wiseman, of Wisemans Ferry, in New South Wales. Robert lived a long life, dying in December 1899 at the age of 103!

Even those with a life sentence could gain their freedom through a ticket-of-leave. With a ticket-of-leave, convicts were still convicts, but they could work for wages or at a trade—unless they committed another crime.

Some convicts were given a conditional pardon. That meant they could not return to Britain, but they were otherwise free to live in Australia. An absolute pardon gave the lucky owner freedom to work anywhere, even back in England.

Many ex-convicts—or ‘emancipists’, as they were called—were not very successful in later life. This was because the ‘exclusives’ or the ‘pure merinos’— people with no convict connections—looked down on them. For example, scientist William Sharp Macleay resigned from the Board of National Education because the attorney-general suggested that Dr William Bland, who had once been convicted for fighting in a duel, should be appointed to the senate of the proposed University of Sydney.

People were not always negative towards ex-convicts. Although explorer and scientist Major Thomas Mitchell once paid a fine rather than sit on a jury that included emancipated convicts, he also believed that convicts were the best people to take on an expedition.

Transportation to New South Wales ended in 1840 and to Van Diemen’s Land in 1853. The Swan River settlement (now Perth) began as a free settlement in 1829, but later accepted convicts as labourers.

Transportation now seems very cruel, but back then people thought it was an acceptable form of punishment.

Convict leg-irons.

Aboriginal resistance

Most Aboriginal people in the southern part of Australia tolerated the presence of the white people who had invaded their lands. Perhaps one of the reasons for this was their belief that white people were the spirits of their relatives who had died and had now returned. In 1790, for example, when John Tarwood and four other convicts found refuge with the Aboriginal people at Port Stephens, north of Sydney, their Aboriginal hosts treated them as returning dead spirits and took them in. They lived in freedom for five years, before the four who were still alive gave themselves up.

It was different in northern Australia, where the Aboriginal people were more likely to attack the foreigners, perhaps because they had already had problems with the fishermen who sometimes visited from Indonesia. Or perhaps Aboriginal culture and beliefs in northern Australia did not include the idea that the newcomers were dead family members.

Ritual spearing

One of the earliest recorded cases of Aboriginal resistance happened near Manly, on the north side of Sydney Harbour, in September 1790, when Governor Arthur Phillip was speared. By 1790, the Aboriginal people were annoyed with the white men because, if the white men found spears or nets on a beach, they would steal them. This was against Aboriginal custom. Historian Inga Clendinnen says that everything in the accounts of the spearing of Governor Phillip points to a ritual spearing, in which Phillip was being punished for crimes committed by members of his ‘tribe’.

Phillip may not have understood this, but it is interesting that he did not order any retaliation after he was wounded. Soon after, one of Phillip’s game hunters, a convict named John McEntire, was speared by an Aboriginal warrior named Pemulwuy. This was almost certainly in retaliation for McEntire’s attacks on the Eora people of the Sydney region.

Unaware of what McEntire had done, Phillip sent out 50 marines, with three days worth of rations, to capture six members of Pemulwuy’s tribe. They took no captives then or in a second attempt, probably because the Aboriginal people in Sydney had sent out warnings about the expedition to those in the bush. Some six weeks after he was speared, McEntire died.

In May 1795, Pemulwuy speared a convict ‘within half a mile of the brickfield huts’—800 metres from where Sydney Town Hall stands today—and got away. Soon after, a convict known as Black Caesar claimed to have killed him. However, in March 1797, Pemulwuy was shot and wounded. He was put in hospital, recovered, and then escaped with an iron shackle still on his leg.

Yagan’s head has since been returned to Australia and buried, but nobody has been able to find the heads of Pemulwuy or Jandamarra.

Pemulwuy now believed that muskets could not kill him, so he led even more attacks, mainly to steal corn from the fields. This suggests that he was not a bloodthirsty killer but a man concerned with providing food for his people, in accordance with their customs. In 1802, Pemulwuy was ambushed and killed. His head was cut off, preserved and sent to London.

Massacres and murders

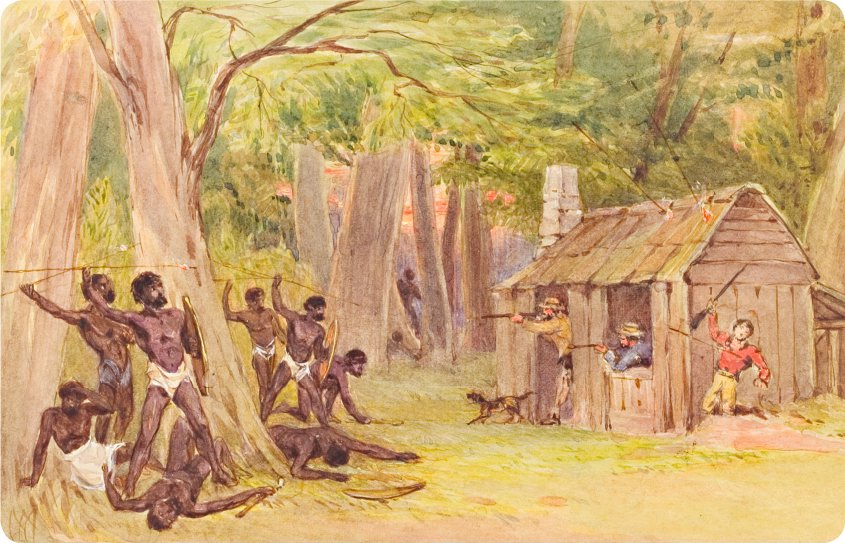

As white settlers moved over the Blue Mountains, they encountered resistance from the original inhabitants. Sheep were kept out in the open in flocks of 400 or 500. Not unreasonably, the Aboriginal people whose land the sheep were on believed they were entitled to spear a few to eat. As the shepherds could be punished for losing sheep, they often retaliated with gunfire. The Aboriginal people then ambushed the shepherds and speared them.

That often led to one-sided war, where white men with guns would wipe out as many Aboriginal people as they could. In the Myall Creek massacre of 1838, an unknown number of Aboriginal people—possibly as many as 30—were killed near Bingara in the New England region of New South Wales. There were 12 attackers. The leader, John Fleming, disappeared, but the other 11 were arrested and put on trial.

A jury of white men found them not guilty, but the law was not finished with them. Seven were put on trial again and, at the end of 1838, they went to the gallows. The other four were not tried a second time.

There were other massacres before and after Myall Creek. There were also some spearings, but through all the killings of Aboriginal people, only a few white men were ever charged and found guilty.

Aboriginal fighters were often killed. Yagan, a Noongar man from near Perth, robbed and killed settlers for several years after the Swan River settlement was set up. He was shot and killed in 1833. The man who killed him cut off Yagan’s head so he could claim a reward, and the head was later sent to England, just like Pemulwuy’s.

Jandamarra was a police tracker in the Kimberley region of Western Australia in the 1890s. After a white policeman arrested some of his Bunuba people, Jandamarra shot the policeman. He then waged a guerrilla war for several years before a tracker from another tribe was forced by the police to hunt him down and kill him. The police then hacked off Jandamarra’s head, leaving his body for his people to bury. His head was also sent to England as a trophy.

Yagan’s head has since been returned to Australia and buried, but nobody has been able to find the heads of Pemulwuy or Jandamarra.

This was a shameful part of Australia’s history.

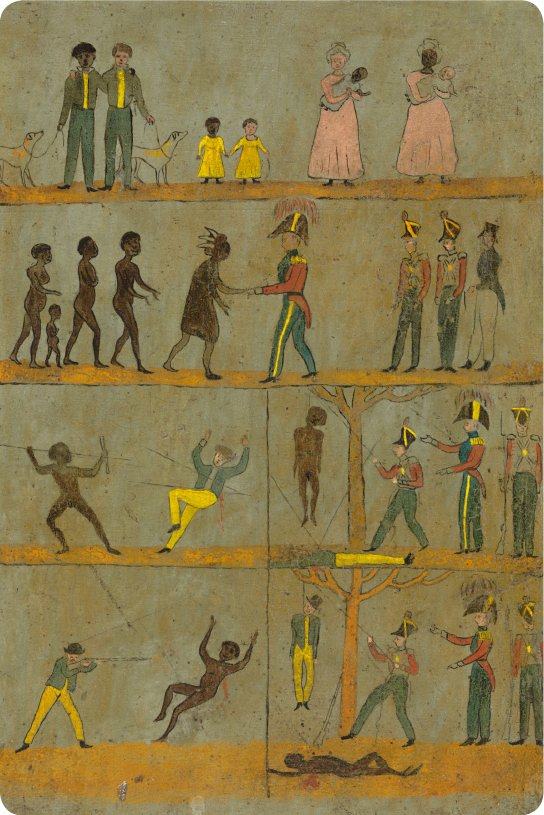

Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur used these pictures to show Aboriginal people how to live peacefully with settlers.

Settling Tasmania

The authorities in the colonies feared Britain’s traditional enemies, the French. The Peace of Amiens ran from March 1802 to May 1803 but, long before it ran out, the British knew war would return. Worse, while French navigator and explorer Nicolas Baudin and his ships had left Sydney in November 1802, it was rumoured that one of his crew had boasted, while drunk, that the French were planning to found a colony in or near Tasmania.

Governor King sent a small vessel to shadow the French ship, and to raise the British flag on King Island, off the north-western tip of Tasmania. Even so, the British still feared that the French would claim part of Australia.

English naval officer and explorer John Hayes mapped the Derwent River in 1793 while on a private exploration paid for by merchants from Calcutta, India. He formally claimed what he called New Albion, but could not get his journal published in India, so he took it to London. His ship was captured by the French, who may have seen his journal. Even if they had not, Frenchman Joseph-Antoine Raymond Bruny d’Entrecasteaux had already visited the Derwent just before Hayes.

In wartime, scientific expeditions were protected, thanks to Sir Joseph Banks, but it was not unreasonable to suspect that some of the French scientists were also looking for places to set up a colony. So action was needed!

Claiming territory

In September 1803, a party of 50 men, under Lieutenant John Bowen, landed at Risdon on the Derwent River, where they struggled to establish a settlement. A few weeks later, Lieutenant-Governor David Collins landed at Sullivan Bay on Port Phillip in Victoria. His party included marines, free settlers and convicts.

The Port Phillip settlement had problems and, in January 1804, Collins took a group to the Derwent River, realised that Risdon was unsuitable and, instead, settled at Sullivans Cove, naming the town Hobart. A second group followed, crossing Bass Strait in May 1804.

In November 1803, The Sydney Gazette reported that war with the French had broken out again, but it was not until December 1804 that Colonel William Paterson settled at Port Dalrymple, near the mouth of the Tamar River in the north. In 1806, Launceston was established further up the Tamar. The Bass Strait area was now fairly safely marked out as British.

In wartime, scientific expeditions were protected, thanks to Sir Joseph Banks, but it was not unreasonable to suspect that some of the French scientists were also looking for places to set up a colony.

Population growth was slow at first, and there were only 1,500 non-Aboriginal people in Van Diemen’s Land (now called Tasmania) in 1816. This figure would have been lower if the settlement at Norfolk Island had not been closed down, with more than 600 people moving from the island to Van Diemen’s Land.

A convict being flogged in the 1850s.

Aboriginal people attacking a settler’s hut in the 1860s.

‘Pleasant’ Van Diemen’s Land

Van Diemen’s Land was a pleasant place where villainy was normal. Even the chaplain was a heavy drinker who ‘played around with the ladies’ and was probably involved in smuggling rum into the colony on the ship Argo.

The pleasantness did not last. Over half a century, Van Diemen’s Land received more than 70,000 convicts, and it became the place where secondary offenders— convicts who had committed another crime after being transported to Australia—were sent. Some 72 such convicts were transported to Van Diemen’s Land from New South Wales in 1845 and 1846. A place was needed where such villains could be punished harshly.

The first place in Van Diemen’s Land to receive convicts was Sarah Island in Macquarie Harbour, on the west coast, in 1822. Between then and its closure 11 years later, about 1,200 prisoners served there, building boats from Huon pine. There are stories of convicts committing another crime in order to be sent there, where they could at least learn a trade.

In 1833, the remaining Sarah Island convicts were transferred to Port Arthur, where conditions were savage. Maria Island on Tasmania’s east coast was intended as a place for rehabilitating convicts, but those prisoners were also sent to Port Arthur. In most people’s minds, ‘Van Diemen’s Land’ meant ‘vicious convicts’.

Aboriginal ‘extinction’

Convicts were not the only people who were ill-treated in the early days of white settlement in Van Diemen’s Land.

Aboriginal people fought the white settlers who were taking over the land where their people had been hunters and gatherers for many thousands of years. They raided white settlements, often in search of food. Many white settlers retaliated by killing or wounding them.

After many years of such guerrilla warfare, martial law was declared between 1828 and 1832 to deal with the ‘black problem’. This period, and the years leading up to it, is often known as the Black War, during which, according to some accounts, many Aboriginal people were massacred.

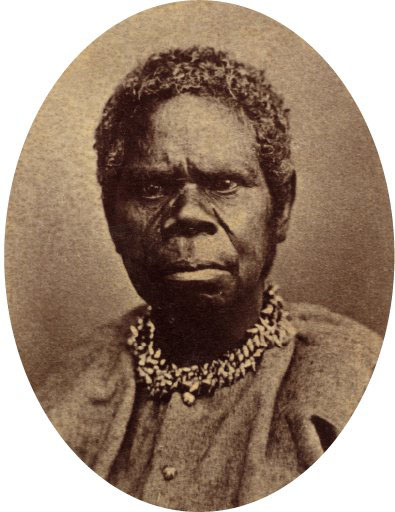

In what is now regarded as a very disrespectful act, after the Tasmanian Aboriginal woman Truganini (above) died and was buried in 1876, her body was dug up. Her skeleton was given to the Royal Society Museum in Hobart, and later displayed there as a scientific curiosity. In 1976, Truganini’s remains were finally given back to her descendants, who had her cremated and scattered her ashes.

In 1830, Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur decided that the only way to stop Aboriginal raids on settlers’ huts was to round up the remaining Aboriginal people and resettle them in one area. Using the same method as for hunting and trapping animals, over 1,000 soldiers and armed settlers swept across the settled areas in what was known as the Black Line. They moved south and east for several weeks in an attempt to herd the Aboriginal people onto the Tasman Peninsula.

While this action was not a great success for the colonists, with only two Aboriginal people captured and three killed, it had such a negative effect on the Aboriginal population at large that many of them later surrendered to Aboriginal ‘protector’ and ‘pacifier’ George Augustus Robinson. They were then taken to a new Aboriginal settlement called Wybalenna, on Flinders Island in Bass Strait.

One of the Aboriginal people who helped Robinson was a Palawa woman known as Truganini. However, she soon realised that this sort of resettlement was not the best thing for her people, and she watched with great sadness as their numbers slowly diminished, with many succumbing to European-introduced diseases such as influenza.

When Truganini died in 1876, the government of Tasmania claimed that she was the last full-blooded Aboriginal person in Tasmania. They officially declared the Aboriginal people of Tasmania ‘extinct’ and no longer a ‘problem’.

It is now acknowledged that some Aboriginal people from Tasmania, including those who had moved to other colonies, outlived Truganini. Many of their descendants, as well as the descendants of Aboriginal people from the Wybalenna settlement, still live in Tasmania today.

The Rum Rebellion

Governor Arthur Phillip arrived in Australia with 696 convicts and 212 marines, including officers. The marines guarded the convicts until 1791, when many of them sailed away and were replaced by an army unit, the New South Wales Corps, better known today as the ‘Rum Corps’.

The Corps’ officers were on half-pay. Like many members of the British army at that time, they were typically trouble-makers, men on parole from military prisons and other undesirables. Three companies came from the army, many arriving as guards with the Second Fleet, and a fourth company came from marines who wanted to stay.

When Governor Phillip left the colony, Major Francis Grose took over. He started changing Phillip’s fair rule. He favoured the Corps and so, by the time Governor John Hunter arrived, the soldiers were in control. Hunter and his successor, Philip Gidley King, were both naval officers, and the army officers of the Corps chose which orders from the governors they would accept and which they would ignore, arguing that naval officers had no authority over them.

When the governors contested this, the Corps’ officers complained about them and had them recalled to England. The members of the Corps kept building up their monopoly control on trade, taking first choice of ships’ cargoes and selling the goods later at a far higher price. They also took over the rum trade and began making rum, distilling it locally—in those days, just about any alcoholic drink was called ‘rum’. They also insisted on paying for goods with rum. No wonder they were later called the Rum Corps.

Breaking Governor Bligh

Governor William Bligh

William Bligh was the next governor of New South Wales. He had clear instructions to break the Corps’ monopoly, because its members were getting rich while the settlers were falling into poverty. Bligh had been a naval captain for about 25 years, and he had been praised by Admiral Lord Nelson for contributing to Britain’s victory in the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801.

Hide and seek

The members of the Rum Corps marched to Government House to arrest Bligh. They were hindered by his daughter, who attacked them with her umbrella. It is said that they then found Bligh under his bed. He claimed he was hiding papers there. He may have been trying to evade capture so he could escape and seek the support of those who opposed the Rum Corps. However, a picture (above) at the time showed a cowardly Bligh hiding under his bed.

Bligh came up against John Macarthur, the son of a draper—a seller of clothing material—from Portsmouth, who bought a commission in the army. Macarthur wanted to be someone important, but he was the sort of person who fought with almost everybody. He went too far when he wounded his commanding officer in a duel, and so he was sent to England to stand trial. After the convenient ‘disappearance’ of all three sets of official papers, the charges against him were dismissed for lack of evidence. Macarthur resigned his army commission and returned to Australia. But, even as a civilian, he was the one who led the people who controlled trade—the monopolists.

The Corps set out to break Governor Bligh as they had broken the previous governors, Hunter and King, but he was ready for them. He visited the settlers, with whom he was popular, and arranged for them to get what they needed from the government stores on credit against the beef, pork, wheat or corn the settlers would later deliver to the stores. Prices at the stores were about a quarter of those charged by the monopolists, and no payments were made in rum.

John Macarthur

The Corps set out to break Governor Bligh as they had broken the previous governors, Hunter and King, but he was ready for them.

Macarthur was both cunning and vindictive. He tried to illegally import stills for making alcohol. When they were seized, he had the man who was sent to seize them, Robert Campbell, charged with theft. Tried under a court made up of Rum Corps officers, Campbell was found guilty. Clearly, this was a challenge to see whether the governor would pardon Campbell, who had been carrying out a legal order. Bligh bided his time.

Then Governor Bligh impounded a ship owned by Macarthur because a convict had escaped on it. Legal wrangling followed, but Macarthur finally went to trial, created an uproar and walked out, thus breaching his bail conditions. He was arrested, but Major Johnston of the New South Wales Corps ordered his release, signing the release papers as ‘Lieutenant-Governor’—a position that he did not hold! After Macarthur was freed, Johnston moved, on 26 January 1808, to depose Governor Bligh in order to ‘restore law and order’.

Bligh was placed under house arrest and ordered to leave for England, which he at first refused to do. In the end, he was allowed to leave on HMS Porpoise, but he had gone only as far as Hobart when the next governor of New South Wales, Lachlan Macquarie, reached Sydney.

A new age had begun.

Macquarie’s legacy

Governor Lachlan Macquarie came with an advantage that the naval governors lacked. He commanded the 73rd Regiment and his soldiers came with him, so he had complete control of law enforcement. As well, John Macarthur had been sent to England for trial and did not return to Australia until 1817, and without Macarthur—or ‘the Perturbator’ as he was called—to lead the monopolists and the Rum Corps who backed them, Macquarie was able to make changes.

Macquarie’s towns

The colony was growing and, until a way was found over the Blue Mountains, Macquarie concentrated on settling the Cumberland Plain in the western area of Sydney. In particular, he set up the five ‘Macquarie towns’ in 1810: Windsor, Richmond, Wilberforce, Pitt Town and Castlereagh.

The towns were all on high ground as a response to a serious flood in the Hawkesbury area in late May 1809. No lives had been lost, but the water had risen 34 feet (10 metres), and an even worse flood had been experienced earlier, so new higher locations were established and laid out. The towns of Newcastle and Parramatta were realigned and expanded during Macquarie’s rule, but his greatest contributions were establishing the town of Bathurst and Sydney’s Macquarie Street precinct.

Bathurst proudly describes itself as Australia’s oldest inland settlement. Its name commemorates the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Bathurst. Few buildings survive from that time, but the overall city plan can still be seen.

After 1814, Macquarie had the help of an architect, Francis Greenway. Greenway had been convicted of forgery and given a sentence of death, which was commuted to 14 years transportation. Within a month of arriving in the colony, Greenway had a ticket-of-leave and was hard at work designing Sydney buildings like the Hyde Park Barracks and St James Church, as well as the Supreme Court just across the road.

Greenway would have loved to have designed a new government house, but Macquarie and his family lived at Government House in Parramatta. Still, Greenway created magnificent stables for the original Sydney Government House, on Bridge Street. Those stables ultimately contributed to Macquarie’s downfall.

The towns of Newcastle and Parramatta were realigned and expanded during Macquarie’s rule, but his greatest contributions were establishing the town of Bathurst and Sydney’s Macquarie Street precinct.

Macquarie also influenced the colony of Van Diemen’s Land. David Collins, the island’s first lieutenant-governor, died in March 1810 and his successor did not take up duty until 1813. In 1811, Macquarie arrived on a tour of inspection.

He ordered James Meehan, the deputy surveyor-general, to lay out a street plan. This covered an area bounded by Sullivans Cove to Liverpool Street, and from Harrington Street to the City Hall. Within this area, buildings still exist in Hobart that were built in Macquarie’s time.

An etching of Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

Just as John Macarthur’s wife, Elizabeth, supervised much of the breeding of merino sheep that her husband claimed to have done, so too Lachlan Macquarie’s wife, also Elizabeth, contributed a great deal to buildings like the Greenway-designed stables for Government House, which are now part of the much-admired Sydney Conservatorium of Music. This building has crenellations—the feature on castles that provide archers with shelter while they are shooting at attackers.

Judge John Bigge was sent from England to look into Macquarie’s greatest gift to the colony—his humane approach to convicts. Macquarie gave convicts a chance to prosper when they had finished their sentences, rather than grinding them down as the ‘pure merinos’, or free settlers, wanted. In other words, Bigge was sent to destroy Macquarie’s reputation, which he did very well.

Little-known architect Henry Kitchen denounced the stables as an ‘egregious folly’—an extremely silly mistake—in his evidence to Commissioner Bigge. Bigge used a number of complaints of this sort to recommend Macquarie’s removal from office.

However, while Bigge is forgotten today by most Australians, Macquarie’s name endures.

Saved for posterity!

There was a scheme in the 1930s to replace the Macquarie Street precinct in Sydney with a modern building that would loom high over the city. Popular legend says that the razing and rebuilding was repeatedly delayed by an unnamed civil servant, who used delaying tactics such as losing the file. Later, World War II made such an ambitious project impossible. So, luckily, we can still admire the beautiful lines of the old ‘Rum Hospital’, the New South Wales Parliament and the Mint.

Establishing Brisbane and Perth

Two new colonies that were later to become state capitals were established in the 1820s, but for very different reasons. As more convicts arrived, new settlements were needed. Some were required to house convicts who had committed extra offences. Ideally, these settlements needed to be far away from other settlements so escapees could not rob free settlers of food and supplies.

Newcastle, called ‘the Coal River’ at first, was set up as a punishment place for secondary offenders but, as settlers moved into the Hunter Valley, the convicts had to move on. In 1823, Moreton Bay was identified as a penal colony but, like ‘Botany Bay’, this was more a label than a location.

Building Brisbane

The original 1824 colony was indeed on Moreton Bay, at Redcliffe but, in 1825, it moved to a site on the Brisbane River, now the city of Brisbane. The commandant until 1830, Patrick Logan, was extremely cruel, and the convicts were very relieved when he was killed by Aboriginal people.

Moreton Bay remained a penal colony until 1839 but, by then, the settlers were closing in again, and the town was opened for free settlement in 1842. Convicts continued to be sent there until 1850 and, in 1859, Queensland became an independent colony.

On the other hand, the Swan River colony in Western Australia was free of convicts for two decades. Some convicts had been sent to Albany in 1826 but, like Adelaide, the settlement that would become Perth was intended to be ‘free’.

The French had been interested in the area. Louis de Freycinet had visited the coast with explorer Nicolas Baudin in 1802 and, in 1818, he was back on the coast of what was then called New Holland. He landed at Shark Bay and took away the plate which Willem de Vlamingh had put up (to show that he had been there) in place of Dirk Hartog’s plate.

The expedition’s papers claimed that it was a purely scientific visit but, even without knowing about the theft of the plate, the British Government suspected the worst and wanted to make a territorial claim. Further south, King George Sound was a known safe harbour, so Albany was established there first, but it often appears in the records under the older name of King George Sound.

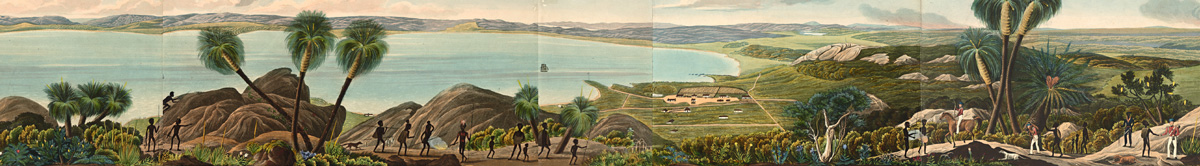

A panorama of the first white settlement in Western Australia, at King George Sound (now Albany).

A cruel commandant

Francis MacNamara—‘Frank the Poet’— wrote about cruel Commandant Patrick Logan in the song, Moreton Bay. The ‘triangle’ mentioned in the lyrics is the frame used to hold convicts while they were being flogged.

For three long years I was beastly treated,

And heavy irons on my legs I wore,

My back with flogging is lacerated,

And often painted with my crimson gore;

And many a man from downright starvation,

Lies mouldering now underneath the clay,

And Captain Logan he had us mangled

At the triangles of Moreton Bay.

Representatives of the British Empire had now grabbed all the best ports and established enough settlements to stop any other European power moving in.

Too many settlers at the Swan River wished to be masters, and too few cared to be servants working for others, so every ship that arrived was met by would-be employers, who usually went away disappointed. Those who settled further down the coast near Margaret River had even more trouble finding people to work for them.

The small colony struggled along, even with a lack of labourers. However, in the 1840s, they asked for convicts as a solution to the labour problem and, between 1850 and 1868, about 9,700 of them reached the colony.

By 1868, the eastern colonies thought themselves ‘pure’. Novelist Anthony Trollope reported that, when he sailed from Fremantle in the late 1860s, he needed to have a certificate, issued and signed by a resident magistrate at the cost of one shilling. Without it, he could not enter South Australia. The certificate read:

I hereby certify that the bearer, A. Trollope, about to proceed to Adelaide per A.S.S. Co.’s steamer, is not and never has been a prisoner of the Crown in Western Australia.

Representatives of the British Empire had now grabbed all the best ports and established enough settlements to stop any other European power moving in. There were unsettled places, but no good sites for colonies.

The making of Adelaide and Melbourne

Two future state capitals seem to have been started without any real intention of marking out territory as British. Adelaide was started to make a dream come true; Melbourne was started by people who just decided it would be a nice place to live.

Both towns began in the mid-1830s, and both were surveyed and planned before any real development happened—unlike Sydney, which just grew in an unplanned way and so stayed crooked, or Hobart, which had to be realigned in 1811. Aside from that, Adelaide and Melbourne were very different.

Laying out Adelaide

Adelaide could have missed out on being South Australia’s capital, because the first governor, naval officer John Hindmarsh, wanted the new town to be on the coast, in an area that would have been flooded regularly.

Luckily, a practical man was on the spot. Colonel William Light had travelled widely and seen a great deal. Appointed as surveyor-general by Hindmarsh, Light gave the city its neat and tidy layout. He selected the Adelaide site because it had running water. When the landholders were called on to vote, Light’s choice won.

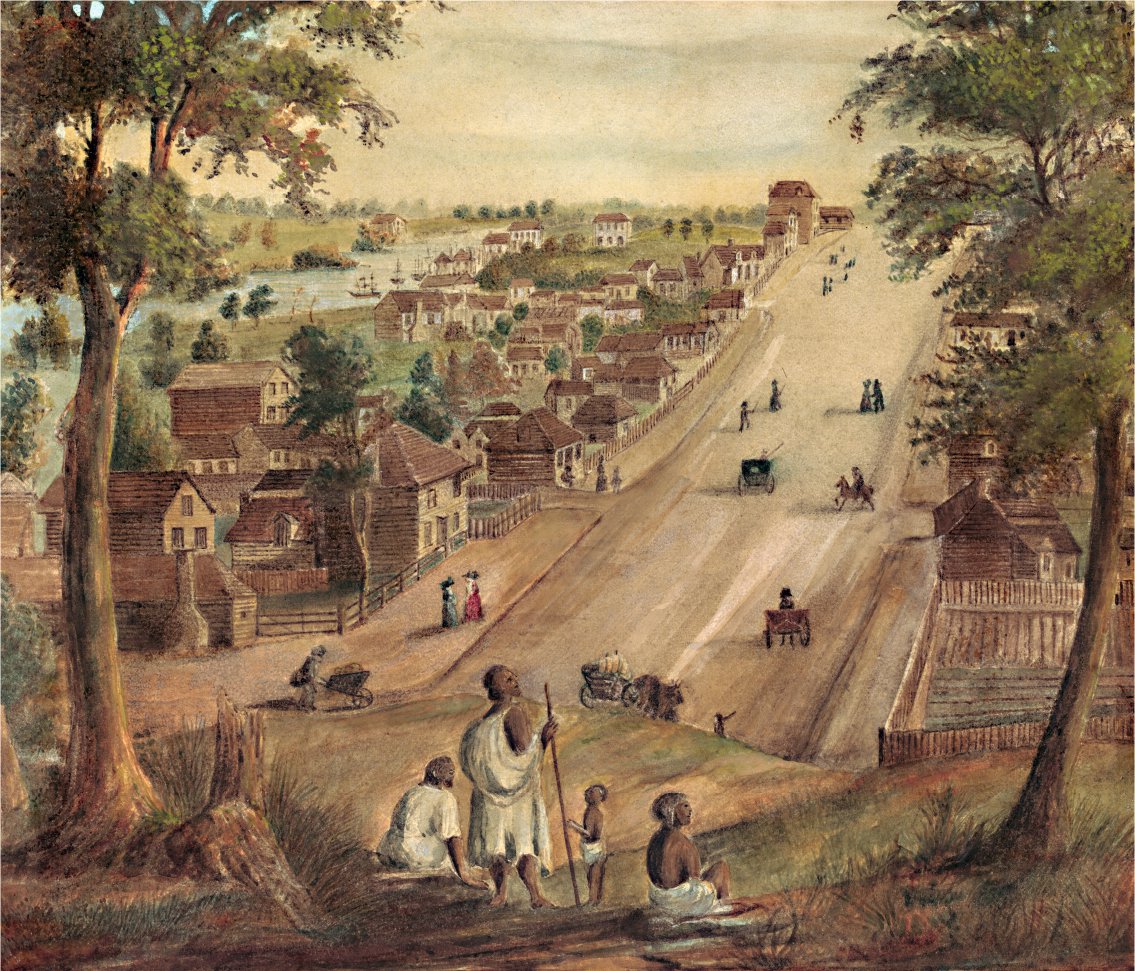

William Knight’s painting of Collins Street, Melbourne, in 1839.

Those migrants who arrived in Adelaide knew nothing about Victoria but, logically, nobody should have gone to Adelaide when land was available at Port Phillip because it was far cheaper there—in fact, often land was just being taken and not paid for.

Light had once seen the city of Catania in Sicily. It was beautiful, with broad streets at right angles to each other. Light’s chosen site, while high enough to be safe from flooding, was flat enough to allow a similar layout, with parkland along the River Torrens forming a green belt around the city area.

South Australia was planned to be free of convicts, and it was. Later, it was proud of its ‘stainless’ foundations. But knowledgeable outsiders grinned at this because the inventor of the whole idea, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, was in jail when he devised his plan.

The colony was established in late December 1836, and by mid-1837 people began to notice that ex-convicts were reaching Adelaide, one way or another. So much for social theory and grand plans!

In the 1850s, Chinese gold-seekers arrived in South Australia to avoid a head tax by landing there and walking to the Victorian goldfields. Former convicts from Western Australia, who were barred from entering Melbourne, followed the same route.

Wakefield’s idea (which did not work) was to survey the land and then sell it at a price that was too high for labourers to afford. The labourers would not totally lose out as they would be given a free passage so they could work hard for the gentry, who could afford to buy the land. That way, after three or four years, the ‘deserving’ among the workers would be able to buy land, while the less ambitious would keep labouring.

Making Melbourne

Those migrants who arrived in Adelaide knew nothing about Victoria but, logically, nobody should have gone to Adelaide when land was available at Port Phillip because it was far cheaper there—in fact, often land was just being taken and not paid for.

The settlement of Victoria began because there were no more free land grants on offer in Van Diemen’s Land. When Thomas Henty arrived in Launceston and learned this in 1832, he asked for 20,000 acres at Portland Bay, across Bass Strait. When he got no answer, he set off across the strait and squatted there in November 1834.

Others, including Melbourne’s founder John Batman, followed and settled on the same bay that Lieutenant-Governor David Collins had tried to settle in 1803, but this time on the Yarra River, where Melbourne is today. By Christmas Day 1836, there were a few slab and weatherboard buildings, some turf huts and many, many tents. That day, the first overlanders brought stock from north of the Murray River into Toorak.

The 180 settlers called their settlement Glenelg, Dutigalla, Beargrass or Bearbrass. The advantage of a private settlement was that you could call it what you liked! In Sydney, Governor Richard Bourke called it illegal, but he sent a small army detachment to Port Phillip, including a surveyor, Robert Russell. Russell drew up a city plan that took no note of existing dwellings, which were then demolished. The City of Melbourne was named by Governor Bourke in 1837 after the British Prime Minister at the time, Lord Melbourne.

In London, the intention was that Port Phillip should be free of convicts, but by the time that news reached Australia, it was far too late. Aside from unofficial convict arrivals, Bourke had sent a five-man convict road-gang to Port Phillip.

In late 1838, the population of Melbourne was more than 2,000, and it was 3,000 by 1839. The number of sheep rocketed from about 300,000 in 1838 to 800,000 in 1840. Australia was growing.

A convicted planner

When Edward Wakefield devised his plan for Adelaide, he was in jail for what was then regarded as the ‘genteel’ crime of attempting to abduct an heiress. He had abducted an heiress before and only got away with it by marrying her. When she died, he tried again. People hinted that he may also have forged documents and perjured himself, but he was never charged with those offences. He was, however, undoubtedly a convict.

Related newspaper articles of the time

No pardons or tickets of leave to be granted at the end of 1816

David Collins plans a survey of Port Dalrymple.

In December 1823, reports were received of abundant fresh water at Moreton Bay.

By June 1824, plans for a settlement were in place.

By 1834, there was a 'South Australian Association'.

In November 1834, people spoke of the 'new colony'.

In December 1834, Colonel Torrens was named as the new governor.

Explore more