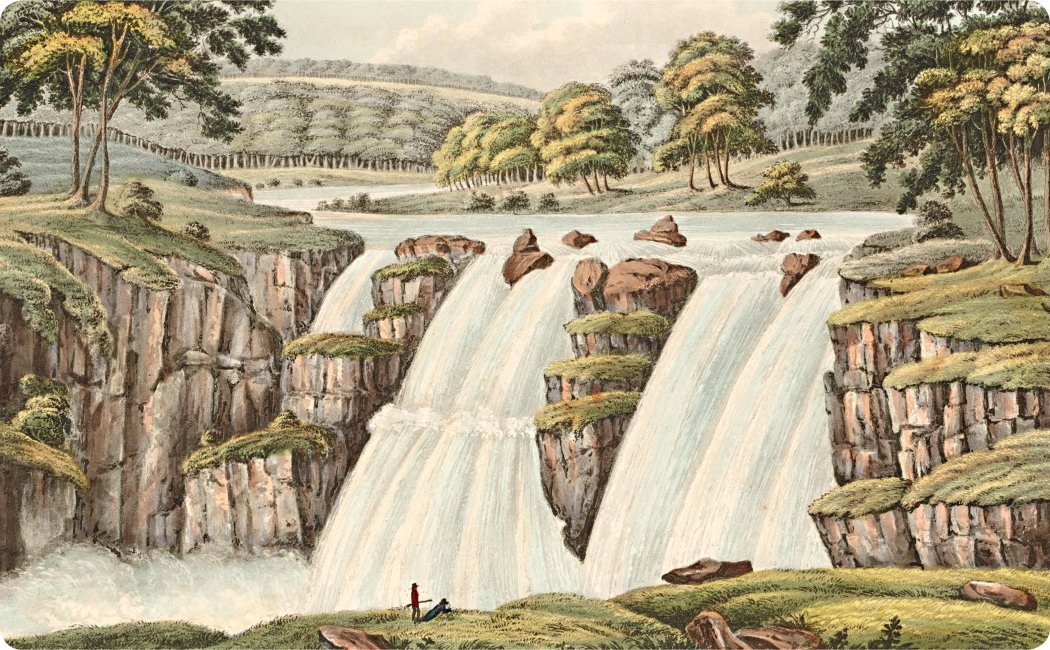

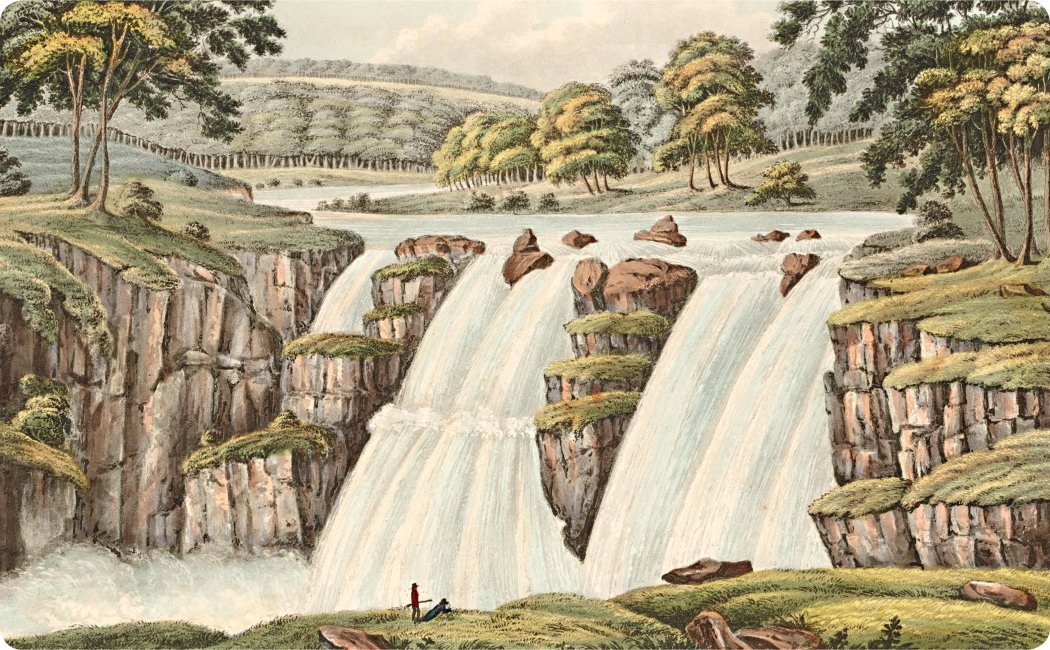

The Bathurst Cataract on the River Apsley in New South Wales in 1824.

Explorers were sent out to explore the land and make maps that showed where people could farm, cut timber, dig up minerals, build telegraph lines and start a settlement. Many explorers hoped to find the fabled ‘Inland Sea’ or to be the first to cross the continent. The most effective explorers were often bush trained. They knew how to follow the faint paths, or ‘native roads’, created by the Aboriginal people who had lived on the land for many thousands of years.

The Bathurst Cataract on the River Apsley in New South Wales in 1824.

Doomed explorer Ludwig Leichhardt.

A cartoon from 1860 of ‘The Great Australian Exploration Race’ between explorers Robert O’Hara Burke and John McDouall Stuart.

Explorer Charles Sturt leaving Adelaide in 1844.

Botany Bay was chosen for the first settlement in Australia because Joseph Banks was impressed with the number of new plant species there. He also thought he saw green fields in the distance. Unfortunately, what he saw were useless swamps on sandy soil. Worse, there was no good supply of fresh water around Botany Bay.

Sydney Cove was a better site because it had water in the Tank Stream and a large safe harbour, but the soil there was just as poor. The first farms at Farm Cove, where Sydney’s Botanic Gardens are today, failed because no introduced plants did well in such sandy soil.

Better soil was found near Rose Hill and Parramatta. Later, people found a few high hills with a cap of shale that made good soil and grew crops there, but many farmers chose to farm on the Hawkesbury river flats. There was just one problem: between 1795 and 1809, four serious floods hit the valley. Away from the flood plains, there was not much good land, but more free settlers were coming to Australia so more farmland was needed.

Along with old settlers and convicts who had served their time, these new settlers wanted farms and land for running sheep and cattle. There was not enough land close to a port where food could be loaded on ships and sent to Sydney.

The Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, provided both challenges for explorers and spectacular views for artists to paint.

Climbing, crossing and colonising

To the west of Sydney, the Blue Mountains were an impenetrable barrier. When people tried to find a way over them, they were always stopped by towering cliffs.

Three settlers—Gregory Blaxland, William Wentworth and William Lawson—are said to have followed the spurs and ridges up to the high ground in the mountains. However, it is more likely that they and their convict servants followed the faint tracks made by Aboriginal people. While Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson reached the top of the Blue Mountains in 1813, they did not go down the other side, so they never actually crossed the mountains.

The first explorer to cross the Blue Mountains was George Evans, in late 1813. On the orders of Governor Macquarie, he explored the land until early 1814. Evans was a good bushman and he found a way down the far side of the mountains.

Settlers soon poured over the Blue Mountains. The first road (called the Big Hill) down the other side was fearfully steep. Carts and drays had to tow a tree trunk behind them to stop the animals from being run over by their own wagons. Later, Major Thomas Mitchell improved the road. By 1815, there was a town at Bathurst.

Soon, more explorers followed, and behind them came wave after wave of settlers—and then came those seeking gold.

Searching for the ‘Inland Sea’

John Oxley

John Oxley had been a naval officer, so he had been trained to use navigational instruments and draw maps. He was appointed surveyor-general of New South Wales in 1812 which, in those days, included all of Australia, except ‘New Holland’ (now Western Australia).

Oxley had been in Australia mapping the coastal areas several times before his appointment, and he turned out to be highly competent at surveying and mapping areas previously unknown to Europeans.

Gangs of convicts built roads over the Blue Mountains to provide better access for settlers.

After five years in New South Wales, Oxley was sent out to find the fabled ‘Inland Sea’. People said it had to exist because west of the Blue Mountains there were many rivers running west, but ships sailing around the coast could find no large rivers flowing into the sea. They thought that meant the rivers must all run into a large lake or sea somewhere in the middle of the continent.

People thought that once boats and ships had access to this sea, most of Australia would be within easy reach, so search parties were sent out to find the Inland Sea. Oxley spent four months going down the Lachlan River from Bathurst in 1817. He returned to the same area past Bathurst in 1818 and headed downriver again.

Making discoveries

Oxley’s second expedition was a complete failure in one sense. He was supposed to find where the Lachlan and Macquarie rivers went, and he did not discover that. On the other hand, he did find plenty of excellent agricultural land.

Oxley was lucky that his party included George Evans, his assistant, the first man to cross the Blue Mountains and reach the Western Plains. At times, the party would divide in two, and Oxley’s and Evans’ parties would meet up again later. He also had with him a volunteer surgeon, or doctor, called John Harris, who came in handy later on.

Oxley’s expedition left on 6 June 1818. At the end of the month, they climbed a small granite hill poking out of the flat plain. Oxley named it Mount Harris, after the surgeon. From there, he saw some mountains that he called Arbuthnot’s Range, now called the Warrumbungle Range. Later, after Evans found the Castlereagh River, he decided to visit this mountain range.

On 8 August, Oxley climbed Mount Exmouth and saw the Great Dividing Range far away to the east. On 18 September, they were on the Apsley River, somewhere near modern Walcha. Oxley wrote that the river was running to the east, and he knew there was a harbour on the coast at about the same latitude.

The entry was marked on naval charts as a ‘bar harbour’, meaning a port where a bar of sand or gravel could be dangerous for shipping, but Oxley knew the marking might have been made only because a bar could be there, and that closer inspection might reveal no bar at all.

They were almost 1,000 metres above sea level, and they had to get their horses down steep slopes but, by 11 October, they had mapped the entrance to what is now Port Macquarie. A few days later, they were travelling along the coast to Newcastle. One man, William Blake, was speared by an Aboriginal man, but surgeon Dr Harris saved Blake’s life.

Oxley and his party were hindered by the many rivers that ran into the sea along the coast, but they found a wooden boat which had survived a wreck and carried it with them, using it to cross the rivers. Eventually, they got to Port Stephens where, on 5 November, Evans and three men went off in the boat to fetch a larger vessel from Newcastle. While Oxley did not find out where the western rivers flowed to, he added a great deal to the map.

In May 1819, Oxley sailed to Port Macquarie in the Lady Nelson, a small vessel well suited for the task. He made a detailed survey of Port Macquarie. Then, in 1823, he was sent out on the Mermaid to examine northern ports, including Port Bowen, Port Curtis (now Gladstone) and Moreton Bay. The report he wrote when he returned led to the creation of the city of Brisbane.

While Oxley died a poor man, he was a successful explorer.

One man, William Blake, was speared by an Aboriginal man, but surgeon Dr Harris saved Blake’s life.

Charles Sturt

Charles Sturt was an army captain when he reached Sydney in 1827. He arrived in charge of a group of convicts, and was made the military secretary of the colony of New South Wales in September of that year.

Sturt had served in Spain in 1813 against the French and in America against the Americans in 1814 but, by 1827, there were few opportunities for army officers to win glory. The world was at peace, so Sturt decided to try to be the first white person to reach the fabled Inland Sea.

Unfortunately, he was no bushman, but he got around that by inviting Hamilton Hume to go with him. Hume had been born in Australia and, as a child, his playmates had included Aboriginal boys. They had run around in the bush together, and so Hume felt at home there.

Heading west

Sturt knew that Oxley’s expedition had been beaten by the swampy ground of the marshes, so he headed out into western New South Wales during a drought. The drought had begun in 1826 and, by the time Sturt left in November 1828, he expected the marshes to have dried out.

On the way west, he visited Dr Harris to learn more about the conditions John Oxley had faced. In December, Sturt, Hume, two soldiers, eight convicts, 13 horses, ten bullocks and one boat travelled down the Macquarie River to Mount Harris. Where Oxley had avoided a swollen river, Sturt found no water. The other rivers were just chains of ponds.

Portrait of Captain Charles Sturt.

Explorers measuring the land and taking sightings in Central Australia in the 1840s.

There were enough waterholes for the party to reach the Darling River in February 1829. They discovered that the water in the river was too salty to drink, but Hume found fresh water nearby. Sturt wrote that Hume’s friendly manner with the Aboriginal people helped them but, further out, the Darling area was deserted. The Aboriginal people who lived there had moved, probably down towards the Murray River where there would be more food.

By late February, Sturt and his party were back at Mount Harris, low on supplies and short of water. They collected fresh supplies there, and then, in late March, they crossed the Darling River, found a ‘dismally brown’ plain, and turned back.

The glass water bottle, with fibre covering, used by Charles Sturt when he went exploring.

Rowing to South Australia

In Sydney, Sturt prepared to head out again. There had been rain, so the rivers were now flowing. Hume did not come, as he had to look after his farm, but Sturt had already learned bushcraft from him. He took a whaleboat that had been taken apart, planning to put it back together later and row down the Murrumbidgee River to find out where it went.

On the way, they called at Hume’s station near Lake George and then crossed the Yass Plains. In early December, they re-assembled the whaleboat and also built another smaller boat from local timber. Sturt sent some of the men back with the drays and then headed down the Murrumbidgee.

In December, Sturt, Hume, two soldiers, eight convicts, 13 horses, ten bullocks and one boat travelled down the Macquarie River to Mount Harris.

Sturt discovered that an ‘acid berry’ eaten by Aboriginal people was very useful for protection against scurvy. That knowledge helped keep Sturt and the members of his party alive when everyone thought they had perished. Even Sturt’s wife believed he was dead and so, when he walked into their house after 17 months away, she was so surprised to see him alive that she fainted, and he had to help her up off the floor.

Sturt and his party had many adventures. They found another river, which Sturt called the Murray. They followed that river to the Darling River junction, and then down to the river’s mouth in Lake Alexandrina in South Australia in early February 1830. They walked over sand hills to the sea, swam in the ocean and collected shellfish to eat.

The easy part was over, and now they had to row back up the Murray, past the Darling, then up the Murrumbidgee to where they had begun. It took them almost three months. After that, it took another month to get to Sydney, where they arrived on 25 May 1830. They had reached the ocean, and so they had shown that the main rivers drained into it and not into an inland sea.

Sturt waited until August 1844 before trying again to find a way through Central Australia. He took a boat, just in case there really was an inland sea that had not as yet been discovered. Instead of finding glory or wealth, he walked into a trap, as a vicious drought began to bite.

Trapped in the desert, Sturt and his party dug an ‘underground room’ and sheltered there until December 1845. Then, even though no rain had fallen, they fled, relying on finding small amounts of water along the way. It was a do-or-die effort, but it worked.

Sturt was one of the great explorers of Australia’s river systems.

Reaching westward

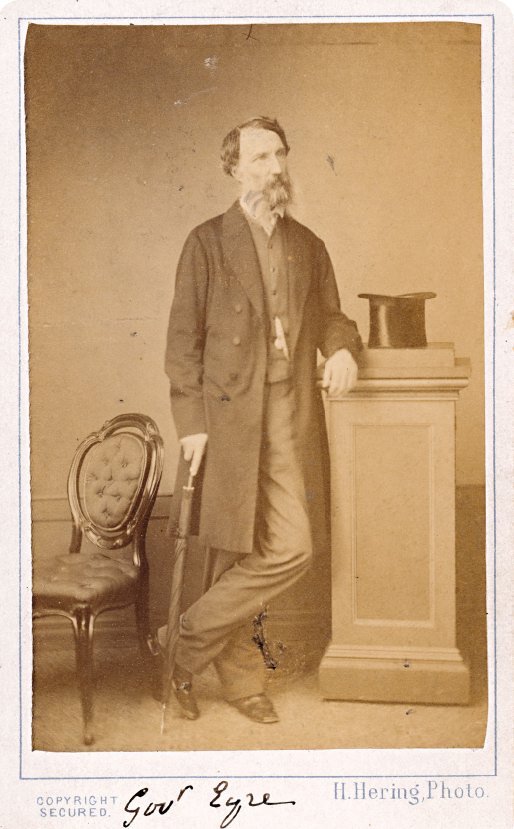

Edward John Eyre

In 1833, an 18-year-old named Edward Eyre slept in the open on his first night in the Australian bush. He had only basic food to eat, but it was enough, and it was more than he would have on many nights to come over the next eight years.

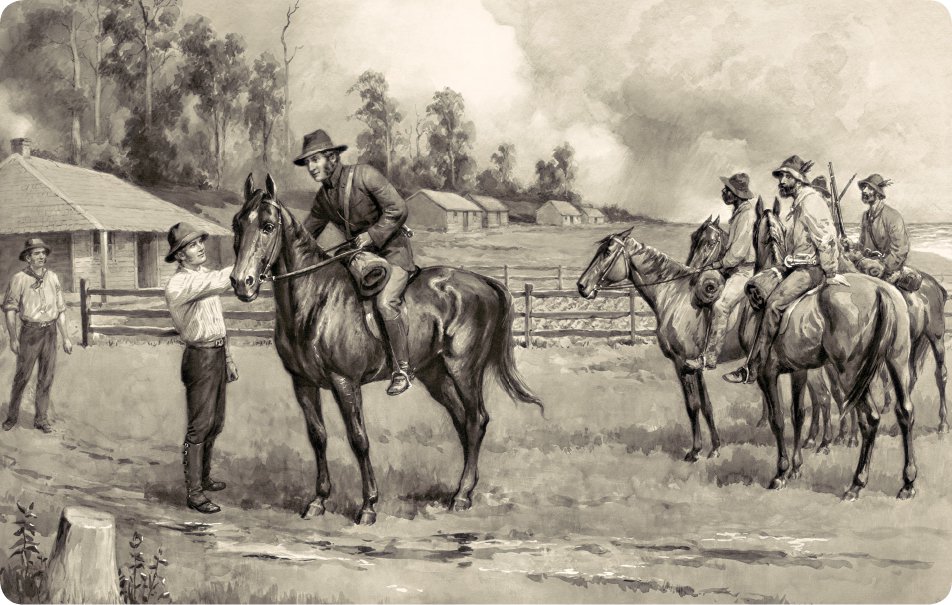

New colonies meant new farms, and farms need animals. When the settlements of Melbourne and Adelaide began in 1836, the men of the Yass Plains knew the lay of the land, thanks to Charles Sturt and Major Mitchell. They started ‘overlanding’—taking stock to the new colonies, trampling down the bush and making tracks that others could follow.

Edward John Eyre’s photographic ‘visiting card’ from the 1860s.

Eyre became an overlander, developing his skills on a trip to Port Phillip. He returned to Sydney, hoping to be the first to move stock overland to Adelaide but, because he could find no water, he arrived second, after Joseph Hawdon and Charles Bonney. He went back to Sydney and took 600 cattle and 1,000 sheep across with him.

He might have become rich in that way but, instead, he chose to go exploring in 1839, looking for useful land. Unfortunately, he had little luck. In 1840, he took sheep and cattle by ship to King George Sound (now Albany), and then overlanded them to the Swan River settlement.

Go west, young man

Eyre took a King George Sound Aboriginal man named Wylie back to Adelaide with him. Eyre wanted to open up an overland route from Adelaide to the west, but Governor George Gawler wanted an expedition to go north, looking for more farming land and a way north out of Adelaide.

Working his way up through the Flinders Ranges in the winter of 1840, Eyre discovered what he took to be a ‘horseshoe lake’ blocking any travel north. He was, in fact, seeing separate lakes but, from a distance, they a way through. appeared to be continuous. He could see no sign of fresh water or grass, so it seemed there was no hope of finding a way through.

Overlanders like these moved stock from station to station over huge distances.

Eyre then said he would go west and try to find a way north around the outside of the lake. Luckily, the governor agreed that he should go west. Eyre had commanded a large party in the Flinders Ranges, but now he reduced it to just John Baxter, his overseer; two Aboriginal men from New South Wales called Joey and Yarry (or Cootachah and Neramberein); and Wylie.

On 7 July, Eyre and Wylie walked into King George Sound, where they found they had long since been given up for dead.

Eyre had become good friends with Sturt, and he must have learned from him about getting on with Aboriginal people, because he certainly got a lot of help from the people he met along the way. He met quite a few because he followed ‘native roads’—well-trodden tracks along the coast.

The local Aboriginal people showed him where to dig for water in the sand dunes. Eyre commented that their ‘language was nearly the same as that of Port Lincoln, intermixed with a few words in use at King George’s Sound’. Obviously, he had come prepared.

As the party of five made their way along the coast, problems developed with the two Aboriginal men from New South Wales. They knew that Eyre had left stores buried at places behind them but, as strangers in that land, they would still have been worried about what lay ahead. Local Aboriginal people had told Eyre about water supplies, but perhaps he did not explain this well enough to his Aboriginal assistants.

Something went wrong and, on 29 April 1841, the two Aboriginal men killed Baxter and then fled with some stolen items. Eyre and Wylie were left to push on alone. Two days later, Eyre saw a Banksia species which he recognised as one that grew at King George Sound.

They might not have made it but, on 2 June, close to Esperance, they came across French whalers who were anchored in Thistle Cove. The whalers looked after them for several days and gave them stores to help them on their way.

On 7 July, Eyre and Wylie walked into King George Sound, where they found they had long since been given up for dead. Eyre, who later became a colonial administrator in South Australia, New Zealand and Jamaica, never went exploring again.

Criss-crossing the country

Thomas Livingstone Mitchell

There are many reasons why we should remember Major Sir Thomas Mitchell. He was an inventor, famous for making a propeller for ships that was based on the shape of a boomerang. He also invented the canvas waterbag. He was a scholar and translator who spoke fluent Portuguese, which he had learned while fighting against Napoleon’s armies in Portugal.

He was also a scientist who found amazing fossils in the Wellington Caves, not far from Dubbo in New South Wales. He was a surveyor who made roads and bridges for the colony. And he gave his name to Mitchell grass and Major Mitchell’s cockatoo. However, he is probably best known in Australia as an explorer.

When Mitchell arrived in Sydney in 1827 as assistant surveyor-general of New South Wales, he was authorised to succeed John Oxley, and so, when Oxley died in May 1828, Mitchell was ready to take over. Because Oxley had been an explorer, Mitchell was keen to go exploring as well.

As an ex-soldier, Mitchell ran his exploration parties along military lines, which made good sense when going out into strange territory. He undertook two minor expeditions and two major ones.

Following ‘the Major’s Line’

In 1831, a runaway convict known as ‘Clarke the Barber’ was captured after having lived for some years with the Kamilaroi people in northern New South Wales. Clarke had a tale to tell. It involved a river called the ‘Kindur’, a fine broad river that flowed to the north-west all the way to the sea. Ships could sail on it, he said.

The pink cockatoo, Lophochroa leadbeateri, often called Major Mitchell’s cockatoo after the explorer.

A navigable river would be better than an inland sea, so Mitchell set off to find the Kindur. He failed, of course, as Clarke had made the whole thing up in an attempt to get a lighter sentence for escaping. Still, Mitchell found some interesting country and filled in some blank areas on the map.

Mitchell’s next expedition was in 1835. He went out to the Darling River and down to somewhere near Menindee. When he clashed with the Aboriginal people there, he backed off.

Misleading information

When explorer Thomas Mitchell reached the junction of the Darling and Murray rivers, he said that he recognised the place right away from an illustration in Sturt’s journal. Interestingly, in 1848, Sturt confessed that he had been almost blind from disease and the illustration was done by a friend based on Sturt’s description. Later, when his eyes were cured, he saw that it looked nothing like the real thing.

On reaching the Victorian coast in 1836, Major Mitchell found the Henty family already settled there.

In 1836, Mitchell began his first major expedition. Starting at Menindee, he planned to go down the Darling and on to either the Murray River or the sea. Because the Darling River was almost dry, he went down the Lachlan River to the Murrumbidgee River.

He reached the Murrumbidgee on 12 May and followed it to the Murray, and then on to where the Darling joined the Murray at Wentworth. Mitchell was now supposed to return, but instead he chose to cross the Murray River because the country looked promising. He found an area that he called ‘Australia Felix’—‘Fortunate Australia’. Even after Port Phillip became a separate colony, it often carried that name. Continuing on down to the coast, Mitchell was surprised to find the Henty family, who had been living there for almost 20 months.

By the time Mitchell returned to Sydney in November 1836, settlers were already landing at Port Phillip and the first overlanders were headed for Melbourne with stock. Soon new arrivals started to go north following Mitchell’s tracks, which were known for many years as ‘the Major’s Line’.

Mitchell went on one more long trip. Like Eyre, he wanted to lead the expedition to Port Essington that was being planned, but Ludwig Leichhardt had beaten him into the field. Instead, Mitchell explored the area near the Maranoa, Warrego and Belyando rivers, hoping to find a good way to Port Essington, some 300 kilometres from modern-day Darwin. He probably still hoped to find Clarke’s imaginary Kindur River. He did not find either Port Essington or the Kindur River.

In many ways, Mitchell was an unusual man. His men probably killed more Aboriginal people, especially near Mount Dispersion, than any other party of explorers, and yet he preferred to use Aboriginal placenames on the maps he drew.

It is hard for us to judge whether the killings were Mitchell’s fault, but he was blamed for them in an inquiry that was completed just after he died.

In 1831, a runaway convict known as ‘Clarke the Barber’ was captured after having lived for some years with the Kamilaroi people in northern New South Wales. Clarke had a tale to tell. It involved a river called the ‘Kindur’, a fine broad river that flowed to the north-west all the way to the sea. Ships could sail on it, he said.

Ludwig Leichhardt

Ludwig Leichhardt arrived in Sydney in 1842. In a technical sense, he was a fugitive from justice because he had not done military service in his native Prussia, as Prussian law required. After his first expedition, he was given a royal pardon by the King of Prussia for serving science so well. The news of this pardon arrived too late, because Leichhardt had gone into the wilderness again and he never returned.

Ludwig Leichhardt and a map of his 1844–45 route from the Darling Downs to Port Essington.

Leichhardt spent two years studying Australian plants, animals and geology—he had previously studied science in Berlin, Paris and London. He learned how to live in the bush, and he wanted to be the first person to find a way from the southern colonies to the small settlement at Port Essington in what is now the Northern Territory.

Heading north

Experienced explorers Sturt, Eyre and Mitchell were all possible leaders of the proposed expedition, so inexperienced Leichhardt had no chance of getting government funding. Instead, he managed to arrange a team of volunteers, funded by private citizens. Leichhardt’s party left Sydney in August 1844.

Leichhardt’s party included a convict, a teenage boy, a bird collector, two Aboriginal men, as well as an African-American and a squatter.

While Major Mitchell was planning to leave from Bourke in New South Wales, Leichhardt made his way from Brisbane through settled districts in the Darling Downs to Jimbour in what is now Queensland, and he left from there in October 1844.

Leichhardt took just enough equipment, using bullocks to carry the load and then eating the bullocks when their cargo was used up. He started with one cart, but it was a nuisance, and when it was damaged in an accident he swapped it at an outstation for three bullocks.

He had a compass, a sextant to calculate latitude and a one-page Arrowsmith’s Map. This simple map was enough, because it gave an accurate depiction of the coastline, mapped from ships by experts. Once he had measured the latitude, he just had to look at the map to see what rivers, mountains or bays were in that latitude, and then he knew where he was.

Leichhardt’s party included a convict, a teenage boy, a bird collector, two Aboriginal men, as well as an African-American and a squatter. The last two turned back soon after they started, but the rest—except for the bird collector, John Gilbert, who was speared to death in an attack by Aboriginal people—reached Port Essington.

What’s for dinner?

Leichhardt and his party ate ‘iguanas, opossums and birds of all kinds’, including rainbow lorikeets. They put the lorikeets in a pot with dried emu, cockatoos and an eagle-hawk. Leichhardt described flying foxes as ‘most delicate eating’, and he also enjoyed eating the feet of young emus. By the end of the journey, they had lost most of their packhorses and so they could no longer carry the botanical specimens they had collected. Leichhardt dumped them but, because they were so desperately hungry, the members of the expedition ate the greenhide case that had contained the specimens!

The attack on John Gilbert was later the subject of gossip among explorers. John Macgillivray, a zoologist, said he had been told that ‘a gross outrage had been committed upon an aboriginal woman a day or two previously, by the two blacks belonging to the expedition’.

We will never know the truth, but Leichhardt usually got on well with Aboriginal people. His party once found themselves among 200 men, women and children, and felt no fear. The Aboriginal people were equally accepting of the strangers, and the key, it seems, was that Leichhardt respected them.

The public had given his party up as lost before news of their success reached the southern colonies. By the time he arrived on 17 December 1845, Leichhardt had travelled around 4,800 kilometres from Brisbane to Port Essington. On their return to Sydney, Leichhardt and his party were cheered loudly and later rewarded.

This determined Prussian adventurer headed out again, this time to cross Australia from east to west. After a false start, he set off once more, but he was never seen again.

Exploring the interior

Burke and Wills

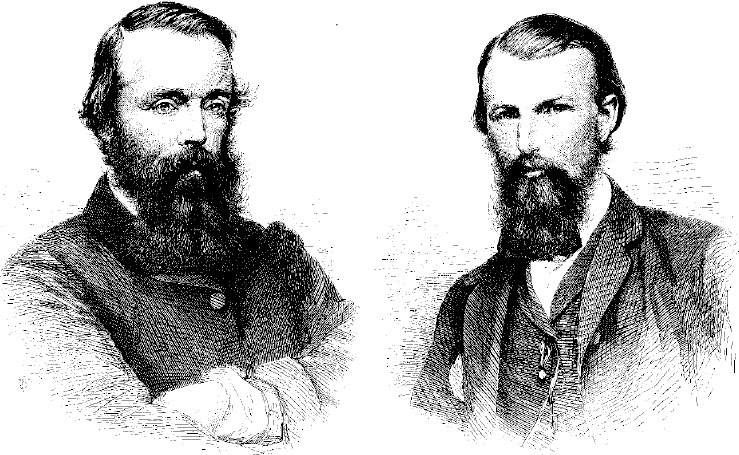

Most explorers knew what they were doing and planned well. However, the people behind the Victorian Exploring Expedition were not well prepared. Today, we call their exploration the ‘Burke and Wills Expedition’, but that is only because William John Wills’ father called it that in a book he wrote after most of the party had died or were scattered across the country.

William John Wills was a competent scientist but he was no bushman, while Robert O’Hara Burke was a police inspector. The planning committee was made up of prominent Melbourne citizens—businessmen not bushmen—who wanted a telegraph line built to link Melbourne to northern Australia and undersea cables to connect Australia to the rest of the world.

Businessmen make profits based on information. The committee wanted a telegraph line built far from either Sydney or Adelaide so that commercial news would go to Melbourne first. Unfortunately for them, the land the Victorian Exploring Expedition had to cross was unknown, and the expedition was competing with the party of John McDouall Stuart, who was seeking a route that ran to Adelaide for Adelaide businessmen.

Most explorers read each other’s published journals and looked at each other’s maps, and many of them knew each other. That was how new explorers learned what to take with them and what to watch out for. There is no evidence that Burke did any of this. Wills might have done so, but he was not involved in the planning. The committee of businessmen made the plans.

A doomed expedition

Burke was told to head north-west from Melbourne and set up a base at Cooper Creek, and then head north, deliberately avoiding country that was already known. The instructions even included a suggestion that the expedition might go right across Australia to the west coast and down to Perth! These orders were completely impractical, and an experienced explorer would have refused to accept them. However, Robert O’Hara Burke was not experienced and did accept them.

The ill-fated explorers, Robert O’Hara Burke (left) and William John Wills (right).

These orders were completely impractical, and an experienced explorer would have refused to accept them. However, Robert O’Hara Burke was not experienced and did accept them.

Despite the fact that the Burke and Wills expedition was largely a disaster, Wills’ father, William, edited and published a one-sided version of his son’s notes and journals as the book, A Successful Exploration through the Interior of Australia (1863).

When they set off on 20 August 1860, it was quite a spectacle, with camels, horses, overloaded carts and people everywhere. And, before long, their troubles began. The expedition had too many supplies, so Burke threw a lot of things away, including the lime juice that would have prevented scurvy. Then his deputy, George Landells, resigned because of Burke’s bad decisions. Wills now became Burke’s deputy.

Burke left half his party behind at Menindee, telling them to take their time moving up to Cooper Creek, where they were to wait. The lead party now had too few competent men in it, but they continued on. They set up a base camp at Cooper Creek, just over the New South Wales border in Queensland.

Stuart planting the British flag on top of the mountain closest to the middle of Australia.

Then, on 16 December 1860, four of them—Burke, Wills, John King and Charles Gray—moved north with six camels, one horse and three months worth of provisions. They pushed on into dry country, but luckily found water and met Aboriginal people, with whom they exchanged beads for fish.

Somewhere near Normanton in Queensland, Burke and Wills left Gray and King at camp 119 and went north until they found a tidal creek. Satisfied that they had found the sea, they turned back. On 13 February 1861, the men headed south.

By 6 March, all four were feeling ill and their food was running out. They began eating the camels, but on 17 April Gray died. The other three all had scurvy, and so did those in the party at Cooper Creek. On 21 April, the men waiting in the base camp at Cooper Creek packed up and left. That very same evening, Burke, Wills and King arrived at the camp and found it deserted.

Burke and Wills died in late June, and only King was alive when a rescue party finally arrived. He lived until 1872.

Burke and Wills had failed to find a good route for a telegraph line, and many men had either died or damaged their health in the attempt.

Crossing the continent

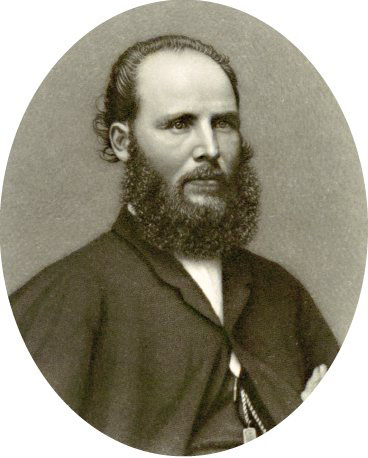

John McDouall Stuart

John McDouall Stuart learned the art of exploring during Charles Sturt’s 1844–45 expedition. Sturt had learned from others, including his good friend, Edward John Eyre.

From working as a surveyor in the outback, Stuart knew how Aboriginal people caught different animals and which desert plants they ate. Clearly, Stuart was well prepared to survive in harsh conditions.

Every year from 1858 to 1862, Stuart probed northwards, identifying routes and water supplies in six attempts to find a way to the northern coast of Australia. On his fourth try, he reached what he believed was the centre of Australia in April 1860. He named a nearby mountain ‘Central Mount Sturt’ after his old leader, but it is now called ‘Central Mount Stuart’. This was caused by a mix-up—a parliamentary paper gave the name as ‘Stuart’ in 1861, but the explorer’s notebooks show that he wrote the name ‘Sturt’. Stuart was extremely loyal, and he received the same loyalty from those who went exploring with him, especially on his last two journeys after he had learned more about selecting the right people. One man, William Kekwick, accompanied Stuart on his last four expeditions, and he was second-in-command in the last three.

Portrait of John McDouall Stuart.

On 11 July 1861, Stuart and his men reached the furthest point in their travels so far. They were only about 600 kilometres from the sea to the north of Australia. Stuart had an idea of where he might head, but no time and no supplies to get there. Their clothes were in tatters, their boots were worn out, and they were running out of tarpaulin to repair their bags.

Stuart had begun his journey with 30 weeks worth of flour. He now had only four weeks worth left, and it was a ten-week long trip to get back to the nearest station in South Australia, Moolooloo. So he had gone two-thirds of the way but had to turn back. He did so knowing where to find water all the way to the northern coast, and which tracks not to follow.

It took eight weeks to get back to Moolooloo. After a short rest, Stuart and his men rode on to Port Augusta and took a steamer to Adelaide, arriving there on 23 September.

Just four weeks later, they headed north again. The trip was not easy for Stuart. He tried to help a horse that had been choked by a rope but the frightened animal reared, knocking him unconscious and crushing his hand. The pain in his hand dogged him throughout his travels. Worse, he knew the symptoms of scurvy and, in late June, it struck him on the Roper River. But the prize was so close that they pushed on despite it.

The trip was not easy for Stuart. He tried to help a horse that had been choked by a rope but the frightened animal reared, knocking him unconscious and crushing his hand.

On 24 July 1862, the front member of the party saw the sea. Stuart had known they were very close but had said nothing, wanting the others to get a nice surprise. Now they had it!

Later that day, they were on the beach at Chambers Bay, east of where Darwin is today, at the very top of the Top End, about 12 degrees south of the Equator. It was low tide, but Stuart walked out to the water.

‘I dipped my feet, and washed my face and hands in the sea, as I promised the late Governor Sir Richard McDonnell I would do if I reached it,’ he wrote in his journal.

They gathered a few shells, looked for and failed to find any seaweed, and then turned around and headed back to Adelaide. They had found a route that provided trees for making telegraph poles and springs for providing water for telegraph stations.

Stuart had succeeded in crossing the continent from south to north.

Read this!

Stuart left a notice in a sealed tin, buried near a marked tree. It said:

The exploring party, under the command of John McDouall Stuart, arrived at this spot on the 25th day of July, 1862, having crossed the entire Continent of Australia from the Southern to the Indian Ocean, passing through the centre.

Botanists and bird collectors

When HM Bark Endeavour dropped anchor in what James Cook later called Botany Bay, there were two botanists on board. They collected plants and animals, including a kangaroo that they shot later in Queensland.

One of Cook’s botanists, Joseph Banks, became President of the Royal Society when he returned to England. He was a powerful man who could get his ideas carried out. As one of his ideas was to settle New South Wales, we could say that Australia was founded on the science of botany!

Banks was aided by naturalist Daniel Solander, but most of the early collectors were medical men (only men because women were not allowed to study medicine at that time). These men knew something about identifying plants and animals, but they were not experts.

There were no scientists in the First Fleet but, as happened during the years of exploration by sea, quite a few people collected specimens. The first real scientist to come to Australia was Robert Brown, a botanist who was sent out to Australia by Banks to go exploring with Matthew Flinders in July 1801. He reached Western Australia in December 1801, and stayed in Australia until 1805.

In 1836, Charles Darwin was the first well-known scientist to reach Australia, although his visit was not noted at the time because it was not until 1859 that he published his iconic book on evolution, The Origin of Species, and became famous.

During his stay, Brown collected around 3,400 species of plants, some 2,000 of which were new to European botanists. He collected plants in many parts of Australia, including Tasmania. He was the first scientist to describe a koala, which he did in a letter to Sir Joseph Banks in 1803. He also took home a live wombat and collected or studied fish, crabs, birds, the platypus and lizards.

In 1836, Charles Darwin was the first well-known scientist to reach Australia, although his visit was not noted at the time because it was not until 1859 that he published his iconic book on evolution, The Origin of Species, and became famous. Then, in 1837, bird enthusiast John Gould reported to the Zoological Society in London on the finches that Darwin had collected in the Galapagos Islands. These finches were to become the cornerstone of Darwin’s groundbreaking explanation of how species evolve.

By 1838, John Gould and his wife Elizabeth were in Hobart. They collected birds themselves, as well as hiring other people to collect birds for them. Gould stuffed the dead birds and sketched them, and then his wife painted pictures of them. Elizabeth Gould was the first of a long line of women painters of Australian animals and flowers.

Exploring caves

Around 1826, artist Augustus Earle painted a picture of the entrance to what he called Mosman’s Cave. It was actually Cathedral Cave, one of the Wellington Caves in the Wellington Valley, New South Wales, named by explorer John Oxley after the Duke of Wellington. Two years later, in 1828, Hamilton Hume, who went exploring with Charles Sturt, wrote a description of the caves and, in 1831, Major Mitchell was in London showing off the bones he had collected in those same caves.

The limestone of the Wellington Caves is from the Devonian period, about 400 million years ago. The stone has only a few fossils in it, but the caves held the bones of many animals that had fallen or wandered in over the last 40,000 years and had not been able to get out. Many of these animals are now extinct, like the marsupial lion, the giant kangaroo and a large relative of the wombat called the Diprotodon.

In 1866, the first proper scientific study was made of the caves. It took Gerard Krefft from the Australian Museum seven days to ride there from Sydney in a horse and cart. It was hard and dusty work in the caves. Krefft’s candles were sometimes smothered by the the choking dust that filled the air, but he still managed to retrieve many fossils.

Others followed Krefft, and 58 species have now been found in the caves. Of these, 30 are now extinct and another 12 are no longer found in the Wellington area. Krefft was also the first to describe the Queensland lungfish. And, because he was bitten so often, he became something of an expert on the symptoms of snakebite.

A kangaroo and her joey from The Mammals of Australia by Gerard Krefft, published in 1871.

Krefft was unusual among Australia’s biologists and naturalists in the 1800s because he accepted Darwin’s theory of evolution. Other biologists were still able to do good work collecting and dissecting new species without accepting the new theory.

When the board of trustees of the Australian Museum sacked Krefft, he said it was a plot by the anti-Darwinists, but anti-Darwin trustee Dr George Bennett resigned to protest against the way Krefft had been treated.

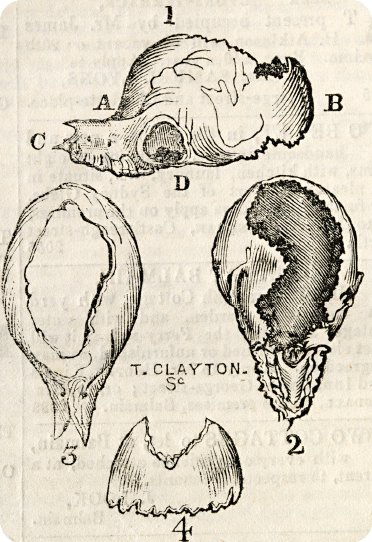

‘Bunyip’ bones, as depicted in The Sydney Morning Herald in 1847.

English scholar and naturalist William Sharp Macleay arrived in Sydney in 1839. While he did not make any great scientific discoveries while in Australia, he did prove that an alleged bunyip skull was nothing of the sort: it was actually the skull of a deformed horse. Despite this, some people continued to believe that the mythical bunyip existed.

Animals laying eggs

Bennett was a very good friend of Sir Richard Owen, the man Krefft accused of engineering the plot against him. Bennett had come to Australia in the 1830s and, for almost 50 years, he tried to establish the truth of something that many colonists already believed—that monotremes, the platypus and the echidna, laid eggs.

In 1883, a young Scotsman, William Hay Caldwell, came to Sydney. He planned to unravel the mysteries of the lungfish, discover if monotremes laid eggs, and find out how marsupials like the kangaroo reproduced. Any one of these would have been enough to make a scientist famous, and yet Caldwell achieved all three—though two of them attracted little interest in Australia.

In 1884, Caldwell proved that monotremes laid eggs. Some people just nodded and said that the Aboriginal people had been telling them that for ages. Caldwell also confirmed what Krefft said about the lungfish, and he added some extra details.

It was his explanation about how marsupials reproduced that really upset people then. He said that a baby kangaroo was born as a tiny embryo. It then made its way into the mother’s pouch, attached itself to the teat and grew there. Bushmen were outraged. They said that the joey began as a bud on the teat. The scientists disagreed with the bushmen, and the scientists were right.

From 1850, Australia started establishing its own universities and, as time went by, training its own scientists. So, in the nineteenth century, Australia not only had biologists, but also chemists, physicists, geologists, engineers, veterinarians and members of all the branches of science that the new nation, which was founded in 1901, would need to prosper.

Related newspaper articles of the time

Death of Mr Ernest Giles. COOLGARDIE, November 14.

References to Georgiana Molloy and her family.

Explore more