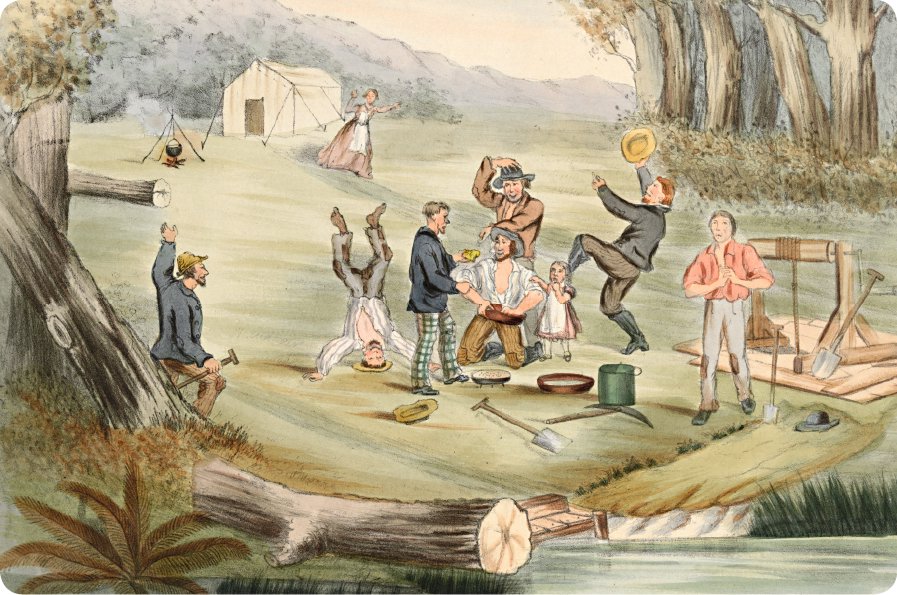

Diggers working with a cradle to find gold.

When it was announced that gold had been discovered in two Australian colonies in the 1850s, the rush was on. Large numbers of people arrived in Australia, with many believing that finding gold would be as easy as digging up potatoes. Some were lucky. They became rich and took their wealth back home. Others found enough gold to buy a farm and settle down in Australia. Others lost everything, but soon found jobs and stayed on. Australia’s economy boomed, and life in the colonies changed forever.

Diggers working with a cradle to find gold.

Excited diggers celebrate finding a gold nugget.

The gold rushes in Australia began in 1851, but people had often found gold before that time, so why did it take so long for a gold rush to begin?

Early discoveries

The first gold ‘discovery’ was faked by a First Fleet convict called James Daley in August 1788. The convicted burglar made his ‘gold’ with filings from a brass buckle and a gold coin. He was flogged for this, and after that people were suspicious of every ‘find’.

In 1824, legend says that an unnamed convict found a gold nugget on what was called the Big Hill—the steep slope on the western side of the Blue Mountains. He was flogged as well (people would have assumed the nugget was made artificially from stolen gold).

In the 1840s, a shepherd named Hugh M’Gregor often sold gold in Sydney. Most people knew he got it from the Wellington Valley, which was on the western edge of where the gold rush would eventually begin.

Gold was found in South Australia in 1843, and it was being mined by 1846. Though the find was not large, it might have started a gold rush but it did not. Neither did an 1847 report by a Cornish miner named John Phillips, who found more gold in South Australia.

In 1849, a shepherd found a large lump of gold, worth two years’ pay, in the Pyrenees Ranges near Melbourne. People rushed off to look for more, but they did not know how to find gold and the police chased them away.

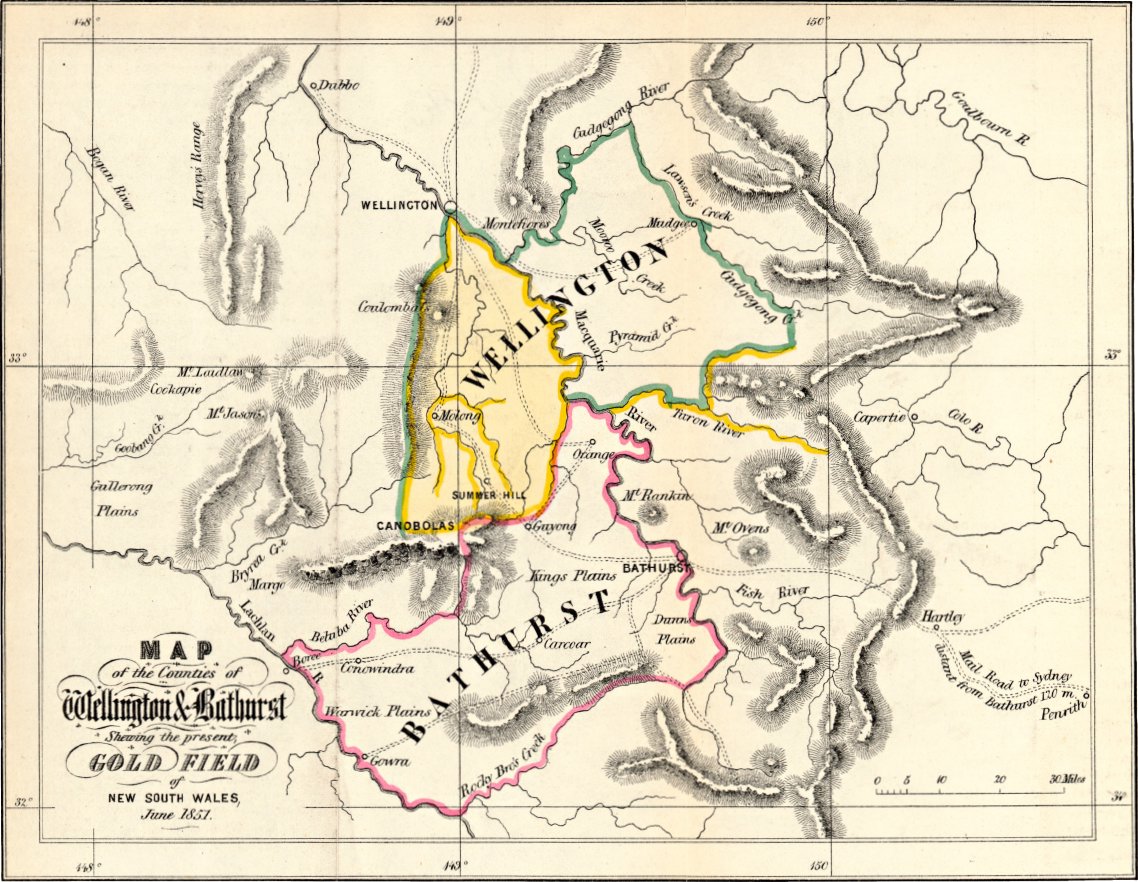

Diggers rushed to buy this 1852 map of the ‘Gold Field’ announced by Edward Hargraves.

The government did not want a gold rush in 1849, but by then news had reached Australia about the gold rush in California, and many adventurous people from Australia sailed off to America. They came back knowing how to look for gold and how to find it.

One of those people was Edward Hammond Hargraves. He had a friend who knew all about the shepherd M’Gregor and his gold. Hargraves had also heard about how the Californian gold rush had started.

When a few nuggets were found on the American River in California, an old miner made a device used to separate gold from dirt. It was called a ‘cradle’, and he showed other people how to make and use it. Some months later, a merchant bought up all the equipment that gold diggers would need. He rode through the streets of San Francisco waving a bottle full of gold shouting, ‘Gold! Gold from the American River!’ The rush began and the merchant made a fortune.

Rushing to the diggings

Many Australian and English geologists knew there was gold in Australia. They even said so, but still there was no gold rush here.

Hargraves knew where the gold was because others had found it. He knew that people coming back from California knew how to use a cradle to get gold. So the trick was to get people excited, and then to stop the government from blocking a gold rush, as they had done in Victoria. He also wanted the credit and any rewards for ‘finding’ gold.

Hargraves wrote a letter to the colonial secretary in April 1851 about his ‘discovery’ of gold between Wellington Valley and the Big Hill but, on the same day, his friend Enoch Rudder wrote to the newspapers declaring that Hargraves had found a large goldfield.

Globetrotters

People rushed to the Australian goldfields from almost every land on the Earth. There are accounts of life on the goldfields from Poles, Americans, Danes, Germans, Italians and Frenchmen. And they all mention seeing people from a multitude of nations, ranging from China to India, New Zealand, Scotland and Africa.

Edward Hargraves, who was celebrated as a hero for ‘finding’ gold.

Now everybody knew, and a few people set off for Bathurst, hunting for gold. The area covered in Hargraves’ letter was too large for the government to be able to stop prospectors. By early May, the first gold hunters reported finding gold, and so the rush began. By mid-May, Sydney’s merchants were clamouring to sell diggers everything they needed. Like the Californian merchant, they knew an easy way to get rich from gold.

In Melbourne, the government was worried about losing workers. They sent a scientist to look for gold in the Pyrenees Ranges, in the central highlands of Victoria. Soon there were goldfields everywhere.

In those days, news spread slowly. A very fast ship might make a one-way trip between Australia and Europe in three months, but four was more usual, and six months was not uncommon. So people in England first heard about the Australian gold rushes in The Times newspaper on 2 September 1851.

Searching for gold

There are two kinds of gold. The easy-to-find gold is loose alluvial gold that has come out of weathered rocks. Alluvial gold gets trapped in creek and river beds, because even a small piece of gold is very heavy. While sand and mud wash away in running water, even tiny bits of gold are left behind, and even tiny bits are worth money.

This sort of gold goes quickly in a gold rush. After that, gold diggers need to crush rocks to get the gold out of them, which is much harder work. That is why people rushed to get to the goldfields quickly.

Families headed to the goldfields, often towing a heavy cart loaded with tools, food and possessions. Each family member was eager to work hard together to win a fortune—or at least to get enough money to buy a farm, animals and seed, with some left over to live on until the farm got going.

Some gold diggers succeeded, some lost all their money, some caught diseases in the unhealthy conditions on the goldfields, and some died of those diseases or were crushed when holes caved in. Most of the gold was under the soil in old, buried creek beds, and so they had to dig down to get it.

The only ones sure to make a profit were storekeepers and sellers of ‘sly grog’—illegal alcohol—along with butchers, bakers, blacksmiths and people who sold ‘medicines’ that claimed to cure everything but usually cured nothing.

And bushrangers did very well too.

Some gold diggers succeeded, some lost all their money, some caught diseases in the unhealthy conditions on the goldfields, and some died of those diseases or were crushed when holes caved in.

Between the start of 1842 and the end of 1851, immigrants and immigration were the subject of numerous articles in Australian newspapers.

Sydney stopped receiving convicts in 1840—although one more convict ship, the Hashemy, arrived in 1849 amid great protests by people against transportation. While the other colonies were still getting fresh convict labour, squatters in New South Wales knew that the supply of cheap labour was drying up.

People tried bringing in ‘coolies’—indentured labourers from China and India who were contracted to work for an employer. In South Australia, some German settlers imported indentured workers from Germany, but this did not work particularly well.

Many people braved the long, tiring and sometimes dangerous voyage to Australia.

Attracting migrants

Some of the squatters wanted to bring back the convict system, but the anti-transportation people had the upper hand. The only solution was to get more immigrants to come to Australia, mainly from Britain. However, Australia was competing with America and Canada, which were closer to Britain, and so the ocean voyage for immigrants was cheaper and shorter. And, if people were going to travel all the way to Australia, they could also go on to New Zealand, which had a cooler climate.

Streets lined with gold

In an article in his newspaper, The Empire, Henry Parkes welcomed the discovery of gold in Australia as a way of stopping the transportation of convicts. He argued that the politicians in Downing Street in London would not want to send burglars and highwaymen to a land full of gold!

This helps to explain the glee with which the start of the gold rush in Australia was greeted. The hope of many colonists was that people would come to dig for gold, and either do well and buy a farm here, or do poorly and settle in Australia anyway to work as labourers. They were right.

Australia benefited from the bad luck of poorly prepared diggers. These people not only found very little gold, but they also had to pay high prices for everything on the goldfields—butchers, bakers, publicans, doctors, blacksmiths and bullock drivers all made huge profits from selling their goods and services.

People who had had a bad experience during their voyage to Australia were also tempted to settle. Between 1851 and 1860, more than 600,000 people reached Australia, with most of them ending up in Victoria.

Some of the gold diggers kept on mining, working underground in the hard-rock mines that replaced alluvial mining. By the time that gold started to run out, many of them were too used to living in Australia to ever want to go back home.

The cities and towns which had been briefly drained of their populations during the gold rushes grew even larger than would have been dreamed of in 1851—and the colonies were also far more democratic, because Australia had the highest quality of life of any nation and, in prosperous times, nobody minded giving the vote to more citizens.

Thanks to the gold rushes, Australia would never be the same again.

Back home, the families of gold diggers hoped for good news from Australia.

The Eureka Stockade

There had been successful revolutions in America and France in the later 1700s and, by the 1840s and 1850s, more people could read, paper was cheaper, printing was faster, and steam transport enabled ideas to spread more quickly. Soon, telegraph wires would link nations and ideas would spread even faster. The desire for change was in the air.

Europe had had a number of failed revolutions in 1848, and refugees had scattered, some of them to the goldfields of Australia. The Victorian colonial government had heard about these revolutions, and Victorian Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe feared what he called the ‘red republicans’.

The wise move would have been to avoid repression, but the squatters wanted the gold diggers back at work on low wages. They wanted to increase the fee for the miner’s licence that everyone on the goldfields had to have—even storekeepers and blacksmiths.

Stoking the fire

In June 1852, La Trobe doubled the licence fee from 30 shillings a month to £3 a month, arguing that it had to go up because of an increase in the cost of administration. But because people were refusing to pay for their licences, the police were sent on ‘digger hunts’. They often robbed their prisoners, and new gold diggers were arrested as they reached the fields, before they could even get a licence.

When a drunken Scot called James Scobie offended publican James Bentley on 7 October 1854, Bentley and his henchmen chased the Scotsman and beat him to death. A corrupt magistrate let Bentley off. On 17 October, a crowd of about 10,000 miners gathered and, in the presence of troopers and a goldfields’ commissioner named Robert Rede, they burned down Bentley’s Eureka Hotel. Bentley had already fled.

On 18 November, Bentley and two accomplices were sentenced to three years of ‘hard labour on the roads’ for Scobie’s death. This might have helped settle things down, but Charles Hotham, who had replaced La Trobe as lieutenant-governor, wanted the ringleaders who burnt down the hotel arrested, and some of them were.

There were more digger hunts, and John D’Ewes, the corrupt magistrate, was dismissed. Then armed troops were sent in. The diggers stopped one group of troops and tipped their carts over. The troops’ drummer boy, John Egan, was shot in the leg. In the commissioner’s camp, people believed Egan was dead, so the soldiers went looking for revenge.

The authorities were alarmed by the demands of the diggers’ Ballarat Reform League. The League wanted things that we now take for granted, such as everyone having the right to vote but, in 1854, that was regarded as a dangerous notion.

Flying the flag

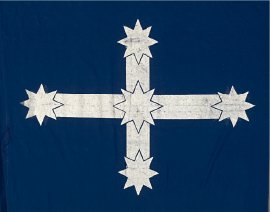

On 30 November 1854, Commissioner Rede sent troops out to check licences, but the diggers had voted not to show their licences, and the troopers were jeered at and stoned. Some arrests were made, but more diggers gathered, the Eureka flag appeared and, beneath it, the diggers swore to uphold their rights and liberties. They started erecting a stockade—a small wooden fort.

A few years later, Victoria was a democratic colony, and two of the Eureka Stockade leaders had become members of parliament.

On Sunday 3 December, thinking there would be no attack on the holy Sabbath, many of those in the stockade drifted away. At 3 am, the troops moved in and, when a shot was heard, their commander, Captain Thomas, shouted: ‘The Queen’s troops have been fired upon. Fire!’

Six troopers and 22 diggers died, and several of those diggers were deliberately murdered, perhaps as revenge for the drummer boy, John Egan. Another 12 diggers were wounded.

Out of 120 prisoners, 13 were charged with high treason, but they were all found not guilty. A few years later, Victoria was a democratic colony, and two of the Eureka Stockade leaders had become members of parliament. The gold diggers won in the end.

A replica of the Eureka flag, which features the Southern Cross.

Related newspaper articles of the time

Calvert's Gold -The tale of a con-man: list of articles.

Wildman's Gold - The tale of a con-man: list of articles.

Daily life, ophthalmia, Bell's Flat, entertainment, coaching, rumours.

The need for sanitation, daily life, coaches.

Chinese goldfield walkers - in that article, look for the 'tag', which will bring up more hits

Explore more