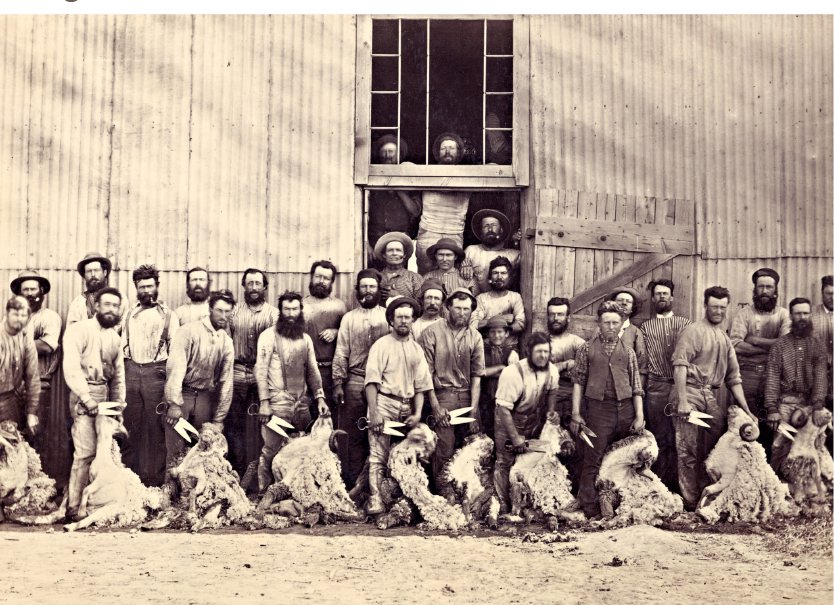

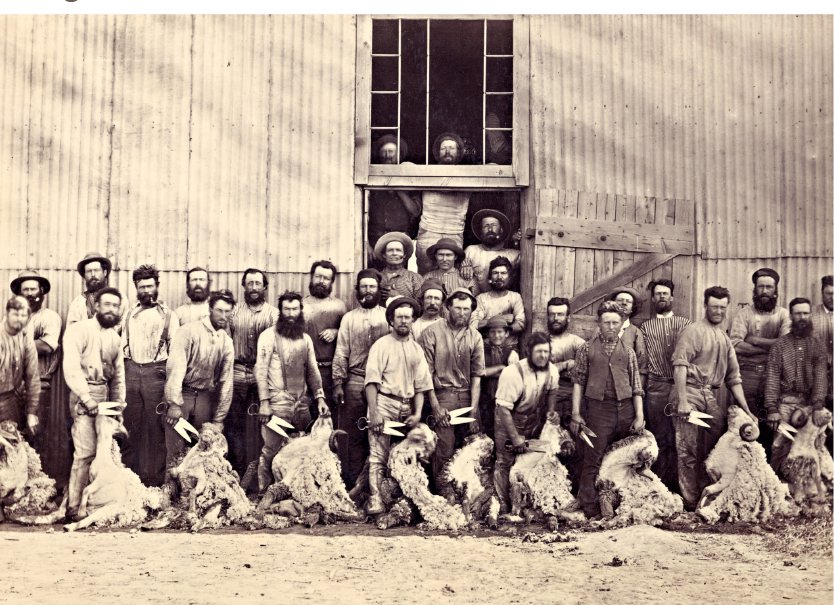

Sheep shearers in front of a woolshed in the 1870s. The shearers’ fight for better conditions led to the formation of the Australian Labor Party.

As more convicts and free settlers arrived in Australia, more of everything was needed. Most free settlers and freed convicts dreamed of owning land, and many thought it was there to be taken. This was not good for the Aboriginal people who inhabited the land. Many of the new farmers also suffered, as they did not know how to work their farms. When they failed, they either worked for wages on the land or drifted to the cities to find work. Australian society changed.

Sheep shearers in front of a woolshed in the 1870s. The shearers’ fight for better conditions led to the formation of the Australian Labor Party.

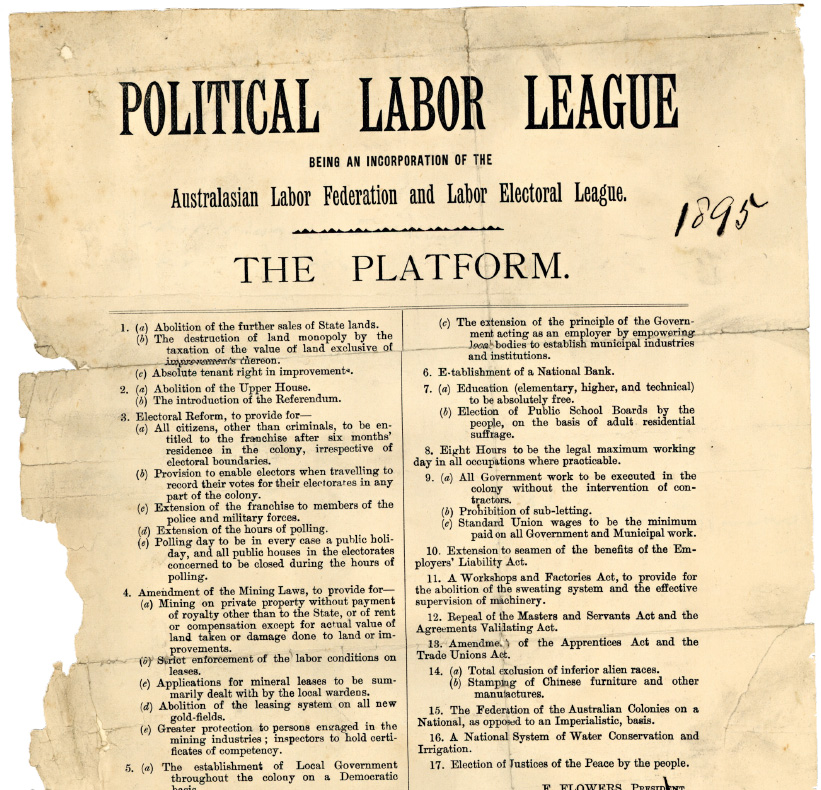

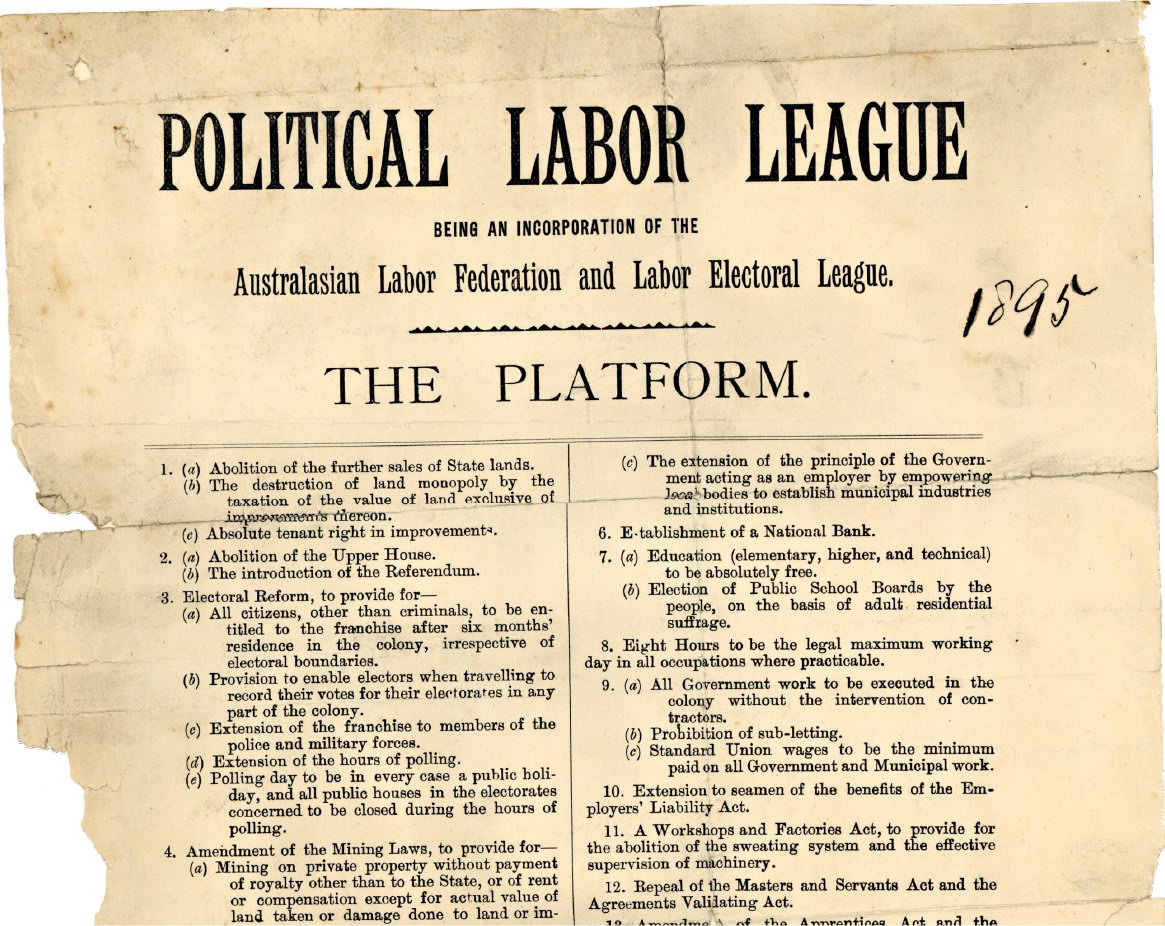

The political platform of what would become the Australian Labor Party.

Australia’s first sheep were bought in Cape Town in South Africa in 1787. There were 44 of them. After 11 weeks at sea, just 29 made it ashore from the First Fleet. A week later, some of them were killed by a lightning strike. Others ate poisonous plants, and convicts stole two and ate them in the bush. One way and another, Australia did not start out looking like a good place to raise sheep!

Sheep are usually chosen for wool or for meat, although you can get wool from a sheep grown for meat and you can eat a sheep that is bred for shearing. The Cape sheep had hairy rather than woolly fleeces, but they tasted good.

During the 1790s, John Macarthur imported Irish and Bengal sheep. Then, in 1797, a ship arrived with 13 merino sheep from Cape Town and John Macarthur took six of them. The breeding of sheep that took place on the Macarthurs’ farm at Camden, New South Wales, over the next 20 years laid the foundation for the Australian wool industry. However, it was mostly Elizabeth Macarthur who bred the sheep, as her husband, John, was out of the colony for almost half that time. Others helped as well, especially the Reverend Samuel Marsden, who some said was more devoted to his woolly flock than the human ‘flock’ in his church.

By 1813, most of the suitable paddocks on the coastal side of the Blue Mountains were full of animals. As soon as a way west was found, sheep, cattle and their attendant humans poured onto the Western Plains.

Keeping up appearances

In the late 1860s, English novelist Anthony Trollope noted the pretensions of the ‘squattocracy’—the wealthy landowners. He said that 100,000 sheep ‘require a professed man-cook and a butler to look after them; forty thousand sheep cannot be shorn without a piano; twenty thousand is the lowest number that renders napkins at dinner imperative’.

Later, as stations got bigger, more shearers were hired, shearing sheds were built to at least provide some shelter for the men while they worked, and rough huts were put up.

Before refrigeration made it possible to freeze meat, the big profit was in wool, which could be baled up and taken to market in wagons hauled by bullocks. Meat sheep were driven to the city to be slaughtered, with the waste going into Darling Harbour in Sydney and, later, into the Yarra River in Melbourne, with other cities acting in a similar way.

A tough job

A sheep farm needed at least 2,000 sheep if it was to make a profit. A grazier with sheep on unfenced country with trees needed workers. One shepherd could mind 500 sheep and, with no fences, shepherds were essential. So were shearers, although at first some of them were drawn from the station staff, with others being hired for the ‘shearing season’.

Shepherds usually used bark huts for shelter, although early Victorian squatter Edward Curr often made his shepherds stay with the sheep overnight. He gave them tarpaulins and forked sticks with which to make tents.

Later, as stations got bigger, more shearers were hired, shearing sheds were built to at least provide some shelter for the men while they worked, and rough huts were put up. The profits poured in and the sheds got bigger. So did the pride of the graziers.

And yet it was not all profits. There could also be disasters, such as when bushfires swept through paddocks or dingoes took the sheep. And, in the early years at least, ‘wild blacks’—who were entitled to be upset at the sheep eating the kangaroos’ fodder—speared the sheep. On the Murray River, the Aboriginal people gave this new food a name—‘jumbuck’.

Then there were the diseases a sheep could get, like catarrh, which was a type of pneumonia caused by a virus. This caused a discharge from the eyes and nose, and later the sheep’s wool fell out. The only treatment was to kill the infected sheep and burn its carcass.

The disease they called ‘scab’ was caused by a mite that burrowed under the skin of the sheep. It made them so itchy that they scratched themselves on rocks, bushes, fences or each other, thus spreading the mites. Some graziers tried killing the sheep and burning their carcasses, but that did not work. Others tried a mercury-and-arsenic-based sheep dip, which poisoned the mites but also killed the sheep. From the 1860s, a solution of tobacco and sulfur was used to kill the mites. The graziers also had to deal with footrot, flystrike and other parasite infestations.

In the 1840s, there was a bad drought and graziers began ‘boiling down’—killing their flocks and boiling them down to get the fat. Sheep fat, called tallow, cost £28 a ton in London. That meant every sheep was worth seven shillings, which was better than nothing.

The good news was that fleeces were getting thicker—in the early 1800s, the Macarthurs got about 1.1 kilograms of fleece per sheep but, by the 1890s, the fleeces weighed about 3.2 kilograms. That was just as well, because the price of wool was falling.

The life of a settler

Finding land

In the 1860s, some of the many land-hungry people who came from the goldfields were allowed to select small portions of a squatter’s run—a part that was leased but not purchased. They were known as ‘selectors’. Where they could, settlers took up land along rivers, so they had water for themselves and their stock and, later on, for limited irrigation. Many of these small farms failed because of the poor, phosphate-deficient Australian soil and so, at the end of the 1800s, many people moved back to the cities.

Building shelter

The first thing any settler did was to build a shelter. Rich settlers might have a tent to sleep in, but putting up a bark hut came high on their list. This involved cutting two zigzag lines around the trunks of a number of trees. The lines were as far apart on the tree as the cutter could reach with an axe. They then used a spade to peel the bark off each tree in a sheet, which they dried over a fire, then laid on the ground under logs to flatten it.

A selector’s bark hut in Gippsland, Victoria, in the 1880s, made from bark sheets and rough timber frames.

The settlers attached the bark to a framework of posts and poles with whatever was handy: wire and greenhide—animal skin—were common. The door might be a flap of canvas or an old sack tacked to the frame, while more bark made a roof.

Clearing the land

Trees close to the hut were cut down to make a firebreak. The land was usually covered in trees or bushes that shaded it and stopped crops or grass from growing. If the farm was a cattle or sheep station, the trees would be ringbarked—deeply cut around the trunk to cut off the water and food supply. This killed them, thus letting sunlight onto the ground beneath.

Many of these small farms failed because of the poor, phosphate-deficient Australian soil and so, at the end of the 1800s, many people moved back to the cities.

If the settler wanted to plant crops, the trees were cut down and the roots dug out. Even those who had stock still needed five acres or so of wheat or maize to provide flour and horse feed. Five acres was two hectares— equivalent to the area covered by 20 Olympic swimming pools—so there was a lot of clearing to do.

During the first year or more, the settler needed enough cash to buy food and feed. The alternative was to go into debt with the local storekeeper. If the settler failed, the storekeeper then took the land as payment and so grew rich.

The Squatting Act of 1836 set a licence fee of £10 to hold a run, added to which was an annual fee of a halfpenny for each animal pastured. Later, the rules became more complicated and the charges went higher.

Surviving in the bush

There were very few doctors then. They were expensive and often not very well trained, and it was only midwives who made urgent house calls to deliver babies. Most householders relied on a book with lists of symptoms and suggested remedies, along with helpful advice on how to pull out an aching tooth or treat a broken bone.

People relied on patent medicines like Davis’ Pain Killer and Porter’s Family Aperient Antibilious Pills. A lady travelling in remote parts of New Zealand was told that if there was no Davis’ Pain Killer, the men used Worcestershire sauce mixed with cayenne pepper. They said it burned just as much, so it had to be doing them good!

Bush people had hundreds of simple solutions to everyday needs. An early Victorian squatter, Edward Curr, described a ‘fat lamp’. It was an old dish with clay in the bottom. The wick was a stick poking out of the clay, with a piece of shirt wrapped around it, and the wick sat in mutton fat from the frying pan.

Schools were scattered around to meet local needs, and children often rode, with several on the same horse, to school each day or walked, barefoot, long distances. The regulations issued to teachers included the specifications for a paddock for the teacher’s horse and the amount of quicklime to be shovelled into the school’s pit toilets.

Moving produce

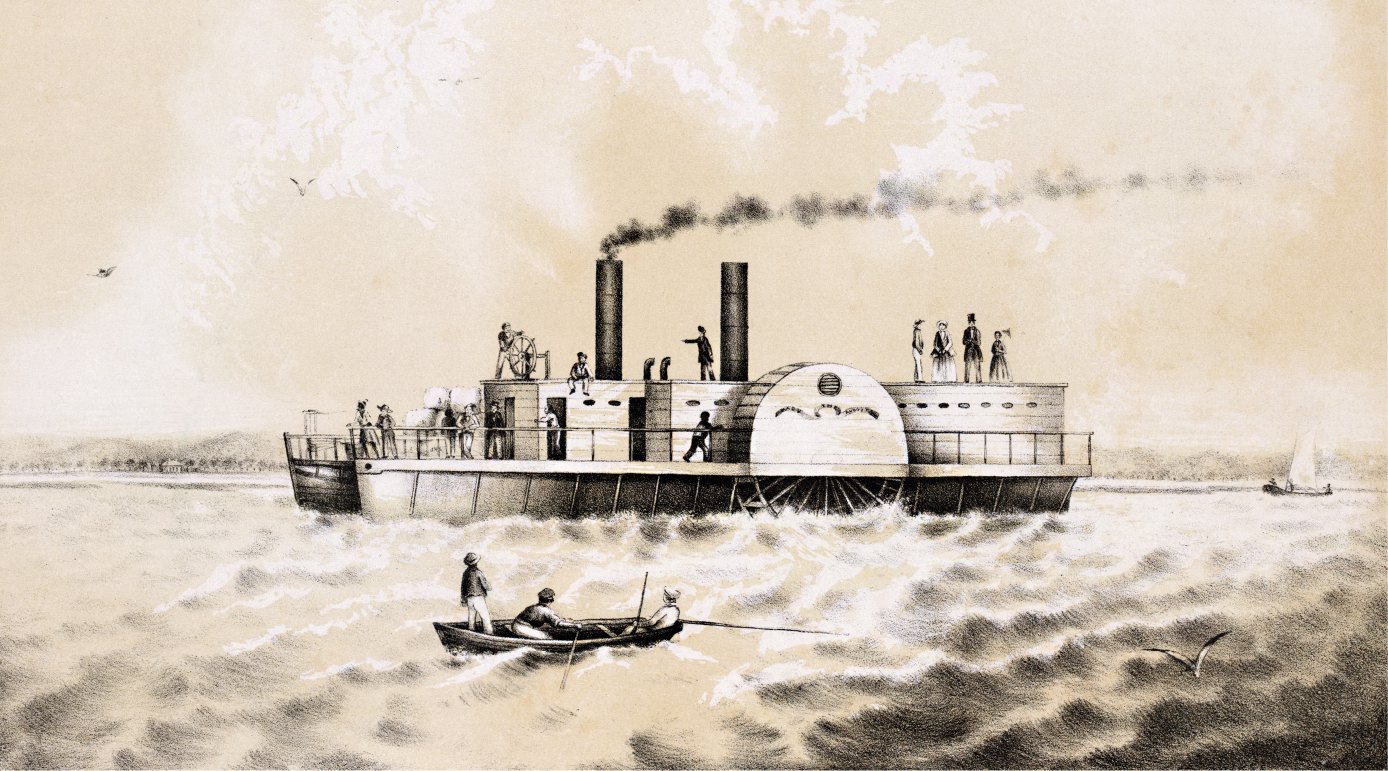

Settlers on the Hunter and Hawkesbury rivers sent produce, including perishables like butter, to large markets by boat in the 1830s. In the early 1850s, a couple of paddle-steamers appeared on the Murray River, and then more entered the Darling and Murrumbidgee rivers.

Australian river boats usually towed one or more barges. When the towing vessel stopped, the heavy barges would often run into the back of the vessel while going downstream or on still water. That is why Australian river boats were usually side-wheelers, not the stern-wheelers used on the Mississippi River in the USA. Wheat and wool used to be taken to Sydney and Melbourne, but now the paddle-steamers took it to Goolwa and then overland to Adelaide to be sold.

Once Sydney and Melbourne realised that their profits were being ‘stolen’ by Adelaide, they quickly built railways to open up the more isolated parts of their states.

The Lady Augusta and the Eureka, the first two vessels to work on the Murray River, in 1854.

Australian agricultural inventions

British soil had been ploughed for hundreds of years and so there were usually no underground surprises in British fields. Australian paddocks were different. Even after the ground was cleared for the plough, even when all the tree stumps had been pulled, burned or blasted out, there was often a tangle of fragments, roots and even rocks lurking in the soil.

A family putting a harvester into storage in the 1890s.

The horse-drawn plough was like a spike that was pulled, point-first, through the soil, opening up the ground so seeds could be dropped in. The ploughman walked behind, holding a handle that kept the plough on line next to the previous furrow and stopping it from tipping forward.

The horse and the operator were both strong and, unless the operator was careful, the plough could break when it hit an obstacle. It was easy to repair, but time was lost, trudging back to the shed—and time was something farmers could not spare during the sowing season.

With a horse ploughing a single furrow, breakage could usually be avoided but, by the 1870s, steam power was replacing horses. Ploughs could now dig multiple furrows, but the operator had lost the ability to stop the plough getting damaged.

The stump-jump plough

Farmers knew it was often just one bolt that broke on a plough, and many must have wondered if the bolt could be replaced by a spring. In 1876, a South Australian named Richard Bowyer Smith worked out a system of weights and levers which allowed a plough to ride up over a rock or a root, and then return to the ploughing position.

Most farmers rejected Smith’s stump-jump plough, saying farmers ought to clear their fields properly in the first place! Richard Smith took out a provisional patent in South Australia for his invention, but he wilted under the criticism and let the patent lapse. Others took up his invention and made a fortune from it, as farmers finally realised they were wrong. In September 1882, Smith was given a £500 ‘bonus’ by the South Australian Legislative Assembly for inventing the stump-jump plough.

In 1876, a South Australian named Richard Bowyer Smith worked out a system of weights and levers which allowed a plough to ride up over a rock or a root, and then return to the ploughing position.

The Ridley stripper

At the same time, a Mr J.W. Bull was awarded £250 for ‘improvements to agricultural machinery’. This was for what is often called the ‘Ridley stripper’, because a man called John Ridley made it using Bull’s design.

In the 1840s, labour was scarce and wheat was harvested by cutting the stalks with a handheld scythe, loading it on wagons and hauling it away for threshing—removing the wheat grains from the stalk. With a scythe, a skilled worker could clear an acre of wheat in a day. The Ridley stripper was a lot cheaper to use than employing workers, but it took off the whole head of wheat, so it still needed to be threshed.

The combine harvester

When H.V. McKay developed his combine harvester in 1884—which threshed as well as stripped the wheat— the entire wheat-harvesting process went from costing 14 pence a bushel to just 4 pence. That meant a big profit for the farmer. Sadly, it also meant less work for labourers, and so many of them drifted to the city.

It also meant farms needed to be larger to justify the cost of buying the machinery, and so many of those on smaller farms also moved off the land.

Bushrangers and outlaws

In the early days of the colony, Governor Philip Gidley King sent men out to find a way over the Blue Mountains. In a report sent to London, he said that they were known locally as ‘bushrangers’. These men were usually not thieves, but just people who ‘ranged’ the bush.

When convicts escaped, a few were cared for by Aboriginal people, but the rest either had to learn how to feed themselves or else rob people. Robbery was easier, and soon many of those who ranged the bush really were thieves.

Black Caesar

Some said bushranger John Black Caesar came from the West Indies, while others said he was born in Madagascar, but nobody really knew. He was transported in the First Fleet for theft, and everybody called him Black Caesar because of his skin colour.

Caesar was a big man who needed more food than he could get from his rations. When he was working, he would steal food and run off into the bush to eat it, and then stay in the bush to avoid punishment. He tried to join Aboriginal groups, but they did not trust him, so he stole food from people’s gardens at night.

When he was caught, he told stories of seeing Aboriginal people herding lost cattle. He also claimed to have killed the Aboriginal warrior Pemulwuy.

But this could not have been true because Caesar was shot by a reward-hunter called John Wimbow in 1796, while Pemulwuy was killed in 1802.

Bold Jack Donohoe

Caesar was never regarded as a hero, but Bold Jack Donohoe was well regarded by other convicts. When he was shot in the forehead and killed in 1830, Major Thomas Mitchell did a delicate pencil drawing of him as he lay in the morgue. Such drawings of dead people were quite common then. A Sydney tobacconist even sold clay pipes with the bowl of the pipe modelled on Donohoe’s head, bullet-hole and all!

Bold Jack was probably also the inspiration for the popular song, The Wild Colonial Boy. Convicts and ex-convicts liked to sing such songs in shanties and pubs, but the owners were warned that they could lose their licences if they did not stop the singing.

A horse saves the day

Sometimes bushrangers did not always get the gold. A man was carrying 800 ounces of gold in his saddlebags when he was bailed up near the Black Forest in Victoria. There was a struggle, and he was dragged from his horse. The horse bolted back to the inn where it was normally stabled. The robbers searched the man and let him go. When he got back to the inn, he found both his horse and his gold safe and sound.

Bushranging on the goldfields

Bushrangers were often seen as heroes because they robbed the rich, but they became less popular in the gold-rush days, when even a poor man might have enough gold to be worth robbing. Many people on the Victorian goldfields were rich, and there were good places on isolated Victorian roads for bushrangers to rob them. Other bushrangers worked the lonely track that went through dry, scrubby bush to Adelaide.

The colonial governments created gold escorts— groups of armed men in blue uniforms, usually retired soldiers, who accompanied sturdy carts filled with gold. On each trip, they were usually joined by a number of armed gold diggers, who saved money by riding with them and not having to pay for the gold escort.

Few bushrangers were as unlucky as the man they called Sam Poo, Australia’s only Chinese bushranger. He started a life of crime in January 1865, but by March of that year he had been shot in the thigh and his skull had been fractured by a blow to the head. He had recovered by year’s end, but he was hanged at Bathurst on 19 December.

In April 1865, ‘Mad Dog’ Daniel Morgan was shot from behind. Many people had worked as his informants, who were able to tell the bushranger which gold diggers were carrying money.

Bushranger ‘Mad Dog’ Daniel Morgan, who was shot dead in 1865.

On one occasion, when a victim claimed he had no money, bushranger Frank Gardiner, who knew for a fact that he did have money, told him that he had received so-much in so-and-so’s bar and had put it into such-and-such a pocket.

Gardiner was one of the few bushrangers to die peacefully as a free man. He was given a pardon on the condition that he left Australia and never returned. He sailed to America and opened a bar in San Francisco, before dropping out of public view.

Ned Kelly

Australia’s best known bushranger, Ned Kelly, dropped from view in a different way in June 1880—through the gallows’ trapdoor and into an unmarked grave. His body, minus its skull, has since been identified and reburied.

The Kelly gang understood technology enough to know that the telegraph was its enemy. The gang’s exploits marked the end of bushranging, because now police reinforcements could be called in by telegraph and they could arrive by train.

The gang planned to derail a police train coming to Glenrowan, but a schoolteacher called Thomas Curnow signalled the train to stop outside the town. The police left the train and surrounded the hotel where the members of the Kelly gang were holed up. Three gang members died in the shootout and in the fire that followed.

After that, thieves looked for safer ways of robbing people. The bushranging era had ended.

Bushrangers were often seen as heroes because they robbed the rich, but they became less popular in the gold-rush days, when even a poor man might have enough gold to be worth robbing.

Boom and bust

The boom of the 1880s

In the 1880s, Australia developed a sense of national pride. In Melbourne, in particular, an economic boom saw the rise of many grand buildings.

The standard of living was higher in Australia than in most other countries in the world. There was low unemployment, wages were rising and many Australians owned their own homes—or hoped to do so before they died.

In 1880, The Bulletin was first published. This was a journal that author Joseph Furphy described in 1897 as ‘temper, democratic; bias, offensively Australian’. It featured Australian writers like Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson, Mary Gilmore, Breaker Morant and C.J. Dennis. Known as the ‘bushman’s bible’, it was the sort of publication that could only have started in prosperous times.

Melbourne held international exhibitions in the new Royal Exhibition Building in 1880 and 1888. Life was good. By 1890, most of the colonies wanted a federated nation, and Melbourne hosted the Australasian Federation Conference in that year.

Money was available to erect many other buildings and, once Ned Kelly was dead, citizens slept soundly at night.

There was a drought in 1883, but in Melbourne things went on as usual. Everybody was sure land prices would keep rising forever, even in 1889 when blocks of land in central Melbourne were nearly the same price as similar blocks in London.

Busy Collins Street, Melbourne, in the 1880s.

The financial scene was dominated by men who were mostly the sons of gold-rush immigrants, and their success was fuelled by suburban train and tram lines, which opened up new suburbs for development.

The depression of the 1890s

Ordinary people and investors got caught up in the excitement of prosperity and began putting their money into building societies and investment companies that offered high interest rates. They did not heed the old warning that when something sounds too good to be true, it usually is.

The financial scene was dominated by men who were mostly the sons of gold-rush immigrants, and their success was fuelled by suburban train and tram lines, which opened up new suburbs for development.

Everybody was supremely confident. But, as victims can always see after the event, there came a time when a few people started to lose confidence and, when that happened, the whole boom collapsed like a house of cards. That happened in late 1891.

The result was a depression that hit hard and lasted for a long time. Most of the investors lost everything, and the people who had caused the depression took refuge in bankruptcy. Some even escaped the embarrassment of bankruptcy by coming to arrangements that were approved by the courts. They paid off their debts at the very low rate of a halfpenny in the pound, which was equivalent to giving creditors $1 for every $480 that they owed them. The ‘boomers’ were free to go on trading through any other firms they happened to own.

Iron lace

A lasting feature of the boom of the 1880s was the cast-iron decoration on many of Melbourne’s buildings. British art critic John Ruskin denounced ‘iron lace’ as cheap and vulgar, but nobody in booming Melbourne cared.

Looking after the workers

In the nineteenth century, even ‘free’ workers had little freedom. The Master and Servant Act let an employer make complaints against employees and have them sentenced to jail for three months. There were few chances for employees to charge an employer, and the magistrates, appointed for their wealth, were unlikely to listen anyway. In theory, the Act was about both sides honouring a contract, but in practice there was little that was honourable.

The thinking of the 1800s is shown by businessman James Macarthur, who told a parliamentary select committee in 1847 that high wages would unsettle the workers, making them less steady and more extravagant. This, he stated, would be against the ‘natural order’. The solution was to bring in more workers, the employers said. Another witness called for 20,000 extra immigrants to be brought to Sydney to bring wages down.

Soon after, Governor Frederick Robe in South Australia gave low-paid work to starving Irish migrants. Employers were furious because they wanted the migrants to be desperate, so they would have to accept much lower pay than the governor was offering.

The name ‘Australian Labor Party’ came after policies such at these below had been developed to help the workers.

The rise of the unions

In a British law passed in 1861, any attempt on the part of workers to form an ‘unlawful Combination or Conspiracy to raise the Rate of Wages’ was an offence, with a penalty of two years in jail. The Combination Act of 1825 was also used to convict and send a group of unionists, known as the Tolpuddle Martyrs, from Dorset in England to Australia in the 1830s.

In Australia, workers wanted things to be different. There were craft unions covering bootmakers, bricklayers, plasterers, qualified butchers, stonemasons and other craftsmen. These unions had achieved an eight-hour day in some trades in both New South Wales and Victoria in 1856. It took longer to achieve in the other colonies, but the bargaining power of the unions was clear to all.

The problem for employers in Australia was that they were faced with all men—but not women—having the vote after 1856. In Britain, the workers most likely to join unions did not get the vote until 1918, so it was easier to pass laws there to stop unions acting effectively.

Striking shearers

The eight-hour day gave city-based unions a better basis on which to negotiate overtime rates. However, workers in the bush were too scattered to organise. Wool prices fell by half from 1875 to 1893, and squatters started cutting shearers’ pay, often by devious means. These included marking sheep with dye to indicate that they had not been properly shorn, or claiming that a shearer’s work was below standard.

The ‘boss’ had the final say. Any shearer who objected and walked off was in breach of his contract and was at the mercy of the law. Under the contract, shearers could be dismissed but they could not leave. Worse, if there was a strike, all the shearers in that shed lost their money.

The troubles that led to the Shearers’ Strike of 1891 began in Victoria in 1886, when some squatters reduced the rate per 100 sheep by about a third. A union was formed and there were several years of skirmishes. While the scab disease was once the sheep farmers’ enemy, farmers now relied on ‘scabs’—non-union labourers. The skirmishes became rougher as unionists began to use force to discourage non-union workers.

By 1889, the Amalgamated Shearers Union had 20,000 members and controlled 2,500 sheds. The pastoralists stood up to the union at Jondaryan on the Darling Downs in Queensland, but they backed down when Rockhampton waterside workers agreed to declare the wool ‘black’ and not load it. Now the police and troops entered the fray.

Twelve union leaders were arrested, charged under the 1825 Combination Act, and sent to jail for three years. In the end, the strikers failed, mainly because their opponents controlled the parliaments, made the laws and decided how to apply these laws.

The Australian Labor Party is born

However, by 1889, a number of union-oriented candidates had stood for parliament, and moves were under way for more to join them. Then, under the ‘Tree of Knowledge’ at Barcaldine in Queensland, a meeting was held that is regarded as the first meeting of the Australian Labor Party. Soon the other colonies formed branches of the Labor Party.

In the middle of 1891, 35 Labor candidates held the balance of power in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly. In 1898, in Queensland, a Labor government held office for one week and, in 1904, there was a Federal Labor government.

The political game had changed.

The pastoralists stood up to the union at Jondaryan on the Darling Downs in Queensland, but they backed down when Rockhampton waterside workers agreed to declare the wool ‘black’ and not load it.

Related newspaper articles of the time

Tales of settlement on the Mornington Peninsula in the 1840s.

The rabbit problem: a history with some key names and dates.

The Rodier method of rabbit control.

A contemporary account of the case of 'Yankee Jack', bushranger.

The trial of the 'Melbourne bushrangers'.

Explore more