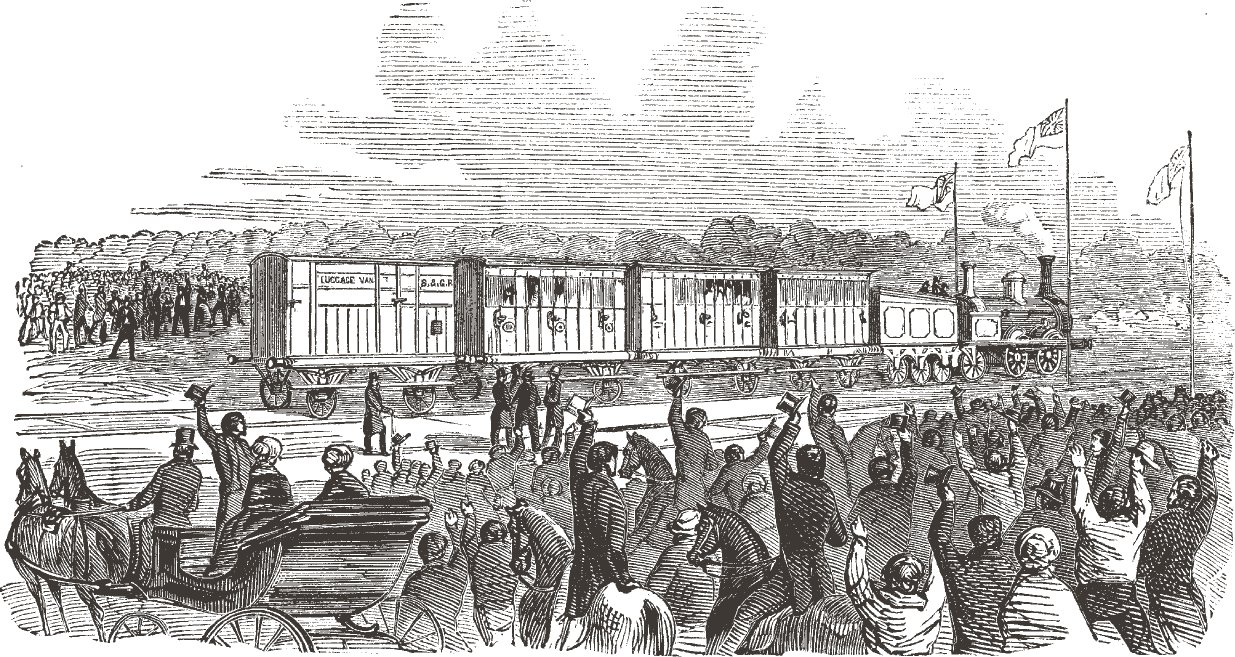

The arrival of the first Sydney train at Parramatta in the mid-1850s.

A number of factors drove the growth of Australian cities. More industry meant more jobs in the cities, and farmers were employing fewer workers. Better transport meant that city workers could get to and from their homes faster and that fresh food could be brought to the cities to feed them. Hygiene was also improving, which meant that cities were becoming healthier places to live in.

The arrival of the first Sydney train at Parramatta in the mid-1850s.

A birds-eye view of Sydney as it was in 1879, with Circular Quay at the bottom of the page, in the middle.

The first town-planning regulations were introduced in 1829 in New South Wales by Governor Ralph Darling, and most other colonies followed the same pattern.

While the majority of Australian towns were laid out by surveyors, others probably just grew by chance. A hotel would be built where a road crossed a river and water was available. A blacksmith would then set up a forge, or a store would open to sell food, nails, tools, cloth and other necessities, and a town would grow.

In the 1800s, Australian cities housed government departments, jails, churches, banks, ports, shops and factories. They also had newspapers, theatres, libraries, bookshops and schools. Later on, they had universities.

The future state capitals—Sydney, Melbourne, Hobart, Adelaide, Perth and Brisbane—were all built near good water supplies, or at least the supplies were good at first. So the location of the Tank Stream and the Yarra, Derwent, Torrens, Swan and Brisbane rivers influenced where these settlements sprang up. When they were first established, few people imagined that the population would ever be greater than a few thousand.

In country towns, rich people built grand homes on hills, away from the dust of the main road and the noise of the local hotel while, in cities, the rich often lived far away from the rush, bustle and smells of inner-city life.

Animals in the city

In 1803, people in Sydney were warned not to let pigs ‘run without being ringed, as they destroy the road’, as a pig cannot dig up the ground with a ring in its nose. In 1809, Sydneysiders who lived near the Tank Stream had to keep their fences repaired so their cattle and pigs would not dirty the water. And nobody was allowed to clean fish or wash in the stream—but they often did.

The Tank Stream, initially a source of pure water for Sydney Town, quickly became a stinking drain.

In 1840, only people wearing high boots could cross Melbourne’s Collins Street, while Sydney’s natural drainage patterns washed everything from the streets down into the Tank Stream, thus polluting the water supply.

In small towns, garbage was either burned, with the smoke blowing away into open country, or it was hauled out of town and left to rot. Human waste was dropped into pit toilets, where the liquids drained away and the solids slowly rotted. In the end, the hole would be filled in with the soil dug from a new pit. This was harder to do in a crowded city—and cities were always crowded, because people crammed into an area small enough for them all to get to work easily each day.

The pigs in the city streets ate some of the waste, and goats and stray dogs cleared away more of it. Then things slowly got better. By 1848, the Police Act in South Australia made it a crime to let pigs or goats stray, or even to tether them on public streets.

With no refrigeration, people often kept a cow for milking, but anyone with three cows or more had to be registered as a dairy. Others preferred to keep goats and, in Melbourne in the 1850s, there were even goat dairies.

Providing goods and services

Those who did not own a milking animal relied on visits from the milkman’s cart. Milkmen collected large cans of milk from the dairies outside the city. In 1859, milkmen in Sydney were sometimes seen topping up the milk cans with ‘water taken from that filthy pond … at the junction of Newtown and Parramatta Roads’. Not surprisingly, Sydney had 124 deaths in November that year, and 75 of the dead were less than five years old.

A parliamentary inquiry in 1859 heard of houses in Woolloomooloo in Sydney where only one out of a hundred had a drain or a sink. Street drainage was another problem. In 1840, only people wearing high boots could cross Melbourne’s Collins Street, while Sydney’s natural drainage patterns washed everything from the streets down into the Tank Stream, thus polluting the water supply. Melbourne’s drains fed into the Yarra River.

Carters made money bringing clean water into the towns. In Sydney, Busby’s Bore delivered swamp water to Hyde Park, where water carts filled their containers by driving the cart under a spout. In other towns, carts were driven into a stream until the containers on the back went under the water and filled up.

Horse-drawn trams and omnibuses were slow, which limited how far a town could spread. However, once railways started running in the 1850s, people were able to move further out of town and escape the crowded and diseased city centres, where diphtheria, typhoid, scarlet fever, tuberculosis and gastric illnesses killed many people. Steam ferries ran in Sydney and, late in the 1800s, electric trams in the main cities helped people escape from the smells, the foul air, the unsanitary conditions and the filthy water.

Spreading disease

Getting away from unhealthy areas was no help when bubonic plague reached Australia early in 1900, first in Adelaide and a few days later in Sydney. Most of the cases occurred in Sydney over the next seven years. Scientists knew in 1899 that people caught the plague when infected rats died and the fleas on them, which carried the disease, moved onto humans and bit them.

Diseased rats often escaped from ships and spread out. When they died, their fleas moved to other rats. While many of the infections came from docks and warehouses near the wharves, other cases were found in distant suburbs. Nobody was safe, but everybody knew that the bubonic plague had come, indirectly, from unsanitary areas.

Infection spread all along the coast but, in Sydney, the government worried about the effects on the coming Federation celebrations. They quickly took over large areas of the dockland, demolishing, clearing and burning down slums and old buildings.

Like other growing Australian cities, Sydney had to clean up its act.

Dealing with disease

Patent medicines called Vitadatio and Dr Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People were advertised as cures for the plague. And, in an effort to fight disease, colonial governments bought all the bleaching powder they could find and spread it around as a ‘disinfectant’. In those days, ‘disinfection’ meant mainly getting rid of the bad smells!

Education

Solomon Wiseman, of Wiseman’s Ferry, near Sydney told Judge Roger Therry that he had given one of his sons a herd of cattle and another a flock of sheep. In five years, said Wiseman, who was a cunning but uneducated man, both boys were rich, and ‘that’s what I call education, for by it they acquire means to live’. However, by the time Therry left the colony, Wiseman’s four sons were bankrupt—they had nothing left.

Useful facts for children

QUESTION: How is Sydney lighted?

ANSWER: By coal gas, which is made at the works of a private company.

QUESTION: Where was the settlement made?

ANSWER: At the head of Sydney Cove on the Tank Stream, where the semi-Circular Quay now stands.

Questions and answers from Miss Johnson’s Geography with Useful Facts for the Junior Classes in Schools, 1859.

In the mid-1830s, Judge Therry supported Governor Richard Bourke’s proposal for state schools. In 1850, the judge was one of the original 16 members of the Senate of the University of Sydney. Things improved slowly but, for a long while, working in the real world was often the only sort of ‘education’ some children experienced.

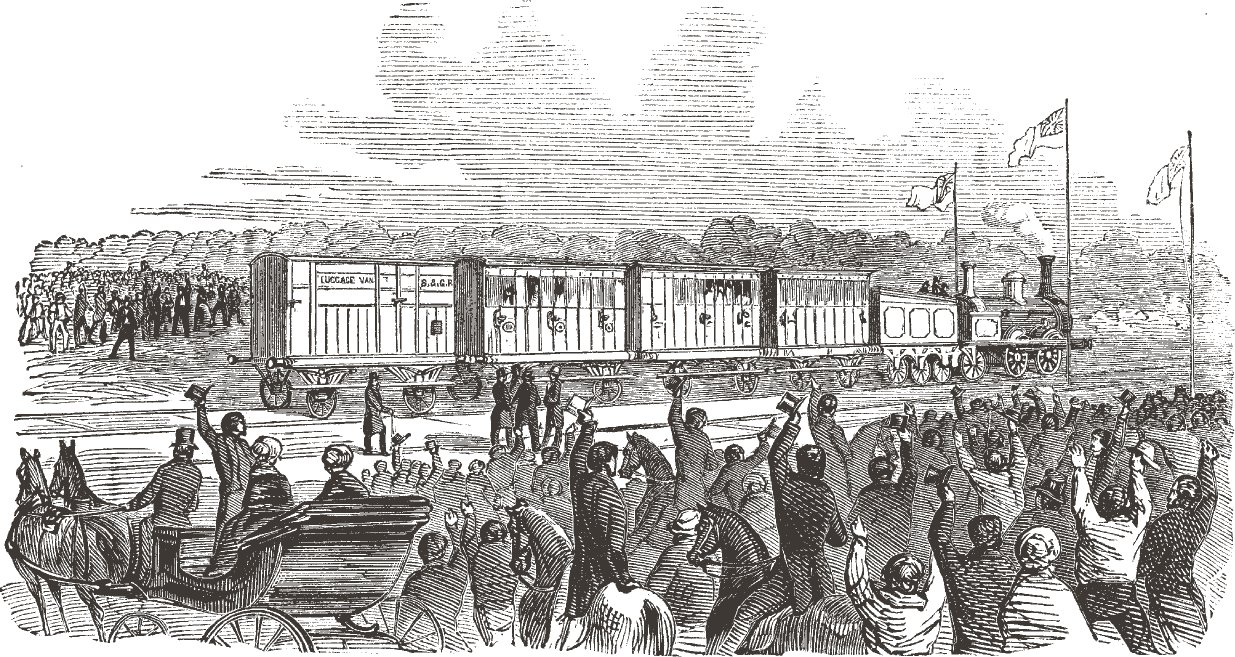

Others learned to read and write at home.

Formal schooling

In the early years of settlement, there were some church schools and a few small private schools but their students were the lucky ones whose parents could afford to pay for the privilege.

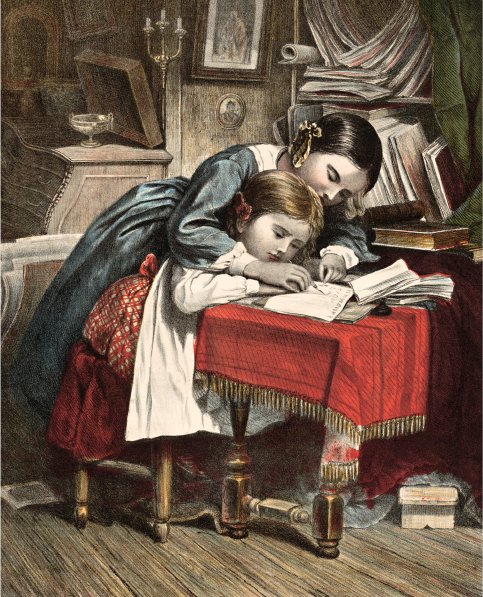

By the 1840s, the first education acts were passed in some colonies. Under the right conditions, a teacher could get a salary from the government, but, in some areas, parents had to pay. The school syllabus included basics like reading, writing and arithmetic, but girls spent 80 minutes a day learning needlework—patching, darning and sewing. During that time, the boys learned geography, geometry and more advanced arithmetic.

The main aim of education then was ‘moral improvement’. The idea was that, if the children of convicts were educated, they would make more of themselves than their parents had done.

Attendance at school was often unreliable. In South Australia, one teacher said in 1848 that, with days off to help on the farm, on average, children attended school for only about 14 days a month. This often meant that there was not enough money to pay the teacher.

The main aim of education then was ‘moral improvement’. The idea was that, if the children of convicts were educated, they would make more of themselves than their parents had done. Most schooling involved the students memorising lists of things like rivers, towns, monarchs or times tables.

In 1872, the wealthy colony of Victoria led the way to something much better, calling for ‘free compulsory and secular’ education. While the education was non-religious, members of the clergy were allowed to enter schools and instruct children in religion.

Newspaper illustrations showing children attending state schools in 1878.

In 1880, New South Wales followed Victoria’s lead, with a legal minimum requirement for attendance at school between the ages of 6 and 14. By then, few children were being born to ex-convicts, so there was less need for ‘moral improvement’, but people had started to care about nation-building and planning for the future. Education mattered.

The skills taught were fairly basic and sometimes not very relevant to children living in Australia. In the second-last year of school in 1885, geography included knowing the chief towns of North America and outlines of the geography of Africa, South America and the West Indies.

In the first five years, pupils were allowed to write only on slates—small hand-held blackboards. Later, children learnt to write neatly with pen and ink on paper, because employers expected it.

Australian literacy rates were on the rise, and literacy could open the door to all sorts of achievements.

Catholic convicts

When the First Fleet sailed for Australia, there was a lot of religious hatred in Britain. Most people from Ireland were Catholics, known as ‘Roman Catholics’ or ‘RCs’. Most Englishmen and Scotsmen were Protestants of one sort or another, and they made life difficult for the Catholics.

Until 1791, Catholics could not practise law in Britain. Before 1829, they could not be members of parliament and, before 1871, only Anglicans could study at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. But the Catholics were not alone, as Jews, Hindus, Muslims, plus some other Protestant denominations such as Baptists and Congregationalists—known as ‘Dissenters’—were also barred.

Some 23 per cent of the convict population of the First Fleet were Catholics, but very few of them were Irish. It is possible that, for transportation, the authorities deliberately selected Catholics, Jews, members of Protestant minorities and people of African descent, because all these groups were over-represented among the convict population, as compared to the general population in England.

After 1800, many Irish Catholic convicts were transported. Even though they were Catholic, they had to attend Anglican Divine Service, as there were no priests and the only clergymen in the colony were Anglican.

Cardinal versus archbishop

In 1901, Catholic Cardinal Patrick Moran argued that a cardinal outranked an archbishop, and so he should ride in front of the Anglican Archbishop of Sydney in the parade celebrating the inauguration of Federation. The authorities in London agreed, but the New South Wales Premier, William Lyne, refused to allow it. Cardinal Moran withdrew from the ceremony. But he did arrange for a choir to appear outside St Mary’s Cathedral to greet the procession with patriotic songs and cheers as it passed by.

The first Catholic priest to arrive in 1800 was Father James Dixon. He was one of a small number of Irish convicts sent to Australia on political charges after an attempt by the Irish to rid themselves of English control in 1798.

Father Dixon was probably convicted because the authorities confused him with his brother, who was definitely a rebel. After he gained a conditional pardon in 1803, Father Dixon was allowed to hold a Catholic religious service each Sunday in Sydney, Liverpool or Parramatta.

This was stopped after ten months. Irish convicts rebelled at Castle Hill in Sydney in 1804 and, after they were defeated, Governor Philip Gidley King forced them to attend Anglican services again, even though Father Dixon had willingly asked the rebels to lay down their arms.

An 1834 painting of the Roman Catholic Chapel in Sydney.

The first official Catholic priests arrived in Sydney in 1820, but by then dislike of Catholics was well in place. The jostling and squabbling between Protestants and Catholics carried on into the twentieth century, although it is rare now.

Politics and religion

Partly because of their origins, either as convicts or as poor immigrants, most (but not all) Irish Catholics were working class, so a large number of the members of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) were Irish Catholics. The party also had quite a few Protestant members, along with agnostics and atheists—people who doubted or did not believe in the existence of God.

In 1916, just as the ALP became used to being in government, its members split over the question of military conscription during the Great War (World War I). Religion also played a part in that division. An Irish rebellion in Dublin in Ireland in April 1916 had been brutally crushed by the British, and so people in Australia with Irish-Catholic roots were unwilling to agree to conscripting soldiers to help the British Empire. The pro-British, pro-conscription members of parliament walked out with Prime Minister Billy Hughes, leaving behind left-wing activists and conservative Irish Catholics.

Soon, the two factions of the ALP fought, and they kept on fighting for most of the twentieth century. Finally, in the 1950s, some of the more extreme Catholic conservatives left the ALP and formed the Democratic Labor Party, which supported the Liberal–Country Party Coalition in successive elections. The conservatives feared that communists, who held power in a number of key unions, would become stronger.

The ALP had lost the one thing that its founders knew a party of mixed religious background had to have— solidarity. Today, religion usually plays little part in Australian politics.

Some 23 per cent of the convict population of the First Fleet were Catholics, but very few of them were Irish.

Communications

Until about the 1880s, most educated people living in Australia called themselves ‘English’ or ‘British’. Even in the 1940s, some Australians saw their country as a ‘branch office’ of England—or, if they had Scottish or Welsh ancestry, as a branch office of Great Britain.

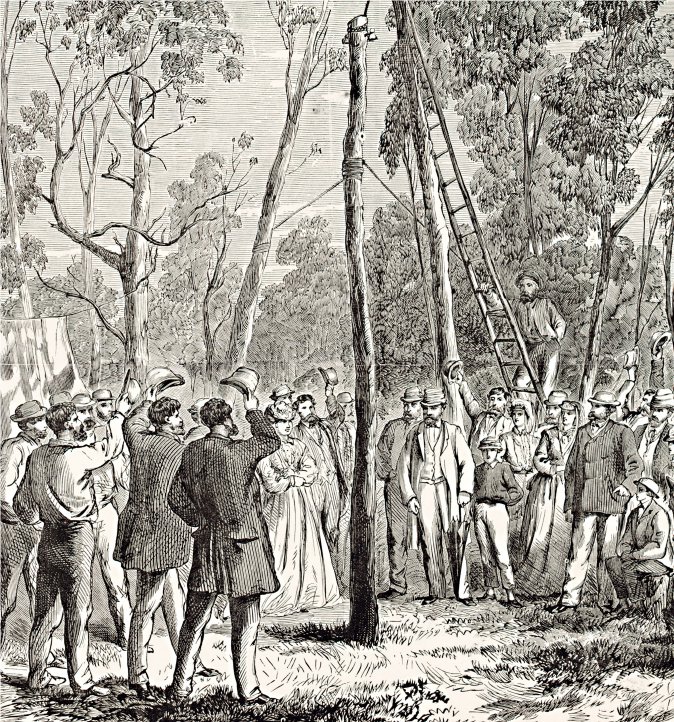

Miss Douglas ‘plants’ the first pole for the Overland Telegraph in September 1870.

The readers of early Australian newspapers often hungered for news of ‘Home’. Writing in the 1890s, journalist Nat Gould told how, before the telegraph cable, pressmen would row down Sydney Harbour to meet the ships, jostling to be first on board to snap up any newspapers.

American Samuel Morse invented the telegraph code in the 1840s and, by 1850, a cable under the sea linked Britain to France. Some fishermen damaged it, but it was soon replaced. By 1858, a cable joined Britain and America. It failed before long, but it was replaced as well.

Communicating across Australia

In 1852, an American writer predicted that undersea cables would one day reach Europe, China and Australia—but, first, telegraph lines were needed in Australia itself.

On 29 October 1858, explorer William Hovell sent the first telegram on the new Sydney-to-Melbourne line. Hovell lived to see Australia’s telegraph system linked to London, but sending a message cost a lot of money. Getting messages to London involved many people and constructing the telegraph line had been very expensive.

By 1855, Britain decided to connect the members of its Empire. A telegraph link from London to India began then, but when what the British called the ‘Indian Mutiny’ and Indians called the ‘First War of Indian Independence’ broke out in 1857, news of the fighting took a long time to reach London. The link between India and London was finally completed in 1859, running sometimes through overland wires on poles and sometimes through undersea cables.

Melbourne was linked by telegraph to Williamstown and Geelong in 1854, and to the main Victorian goldfields by 1857. By 1858, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide were all connected. Soon, the workers who strung the wires were back adding more lines to the poles. A second line soon went from Sydney, through Deniliquin, to Melbourne and Adelaide. In 1859, a cable under the sea from Cape Otway linked Victoria to Tasmania.

Communicating with the world

Overseas news often spread fast once it got to Australia, but it usually took a while to get here. In fact, it could take nearly three months for important news from Europe to reach Australia.

By 1859, international agreements were in place. Britain would run a cable from India to Singapore. Then the Dutch, who controlled Indonesia, would lay a line from Singapore to Banyuwangi in eastern Java, just across the water from Bali. The Australian colonies would pay for the next link to the Australian coast, and also for the wiring to hook up with the Australian system. However, first they needed a route for what became known as the Overland Telegraph.

‘The cable flashes the latest intelligence from one side of the world to the other, and anything of importance that has taken place in the old world is soon learned in the new.’

The Overland Telegraph

In 1859, the South Australian Government offered £2,000 to the first person to cross the continent and reach the north coast. John McDouall Stuart took up the challenge and triumphed in 1862. His route passed through timbered areas where telegraph poles could be cut. It also went past water sources where telegraph stations could be set up, and where staff would receive and send on messages. It was also a route for supply parties to travel along.

Until that was done, important news from ‘Home’—Great Britain—came very slowly. For example, Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, died of typhoid fever on 14 December 1861, but his death was not announced in the Australian newspapers until 28 February 1862.

By January 1872, a telegraph cable linked Britain to America, and cables crossed the USA, so news could come to Australia by steamer from San Francisco in barely six weeks, about half the time for news to come by ship from Britain. In January 1872, Australians received the alarming news via steamer that the Prince of Wales was dying of typhoid fever. Luckily, a cable linking Java to Port Darwin had been finished two months earlier, and so the cheering news that the Prince of Wales was recovering was received at almost the same time via a telegram from the Suez Canal. The good news was reported in The Illustrated Sydney News of 20 January 1872.

First with the news

We have this day, within two years, completed a line of communications two thousand miles long through the very centre of Australia, until a few years ago a Terra Incognita believed to be a desert.

The contents of the first telegraph sent on the completed Overland Telegraph by Charles Todd, 22 August 1872.

Australia was still three or four weeks behind the rest of the globe in receiving news from Europe, but that would change once the colony of South Australia completed the link. The final work took longer than expected, but the first message was sent on 22 August 1872 by Charles Todd, who had directed the building of the telegraph lines.

In 1896, journalist Nat Gould described the Overland Telegraph as a wonder: ‘The cable flashes the latest intelligence from one side of the world to the other, and anything of importance that has taken place in the old world is soon learned in the new’.

Communication with the rest of the world was now a reality. News now took just hours to reach Australia.

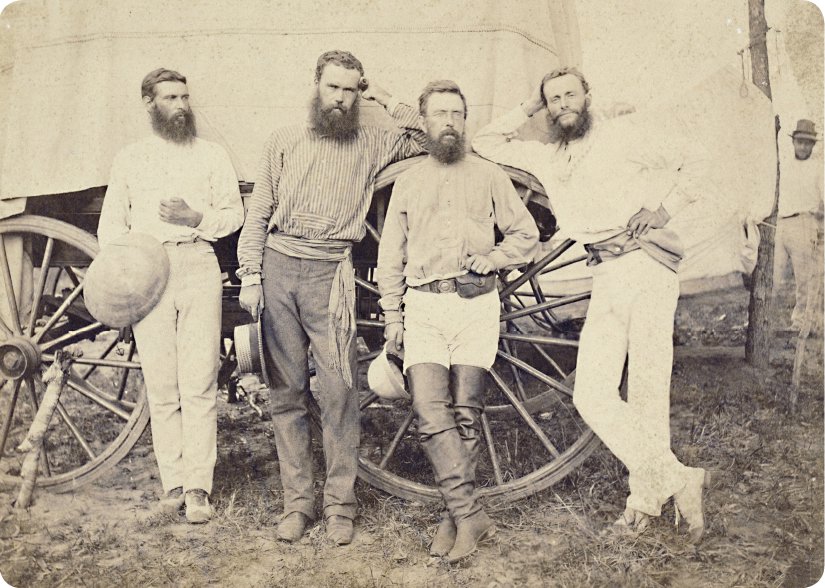

A party of Overland Telegraph workers, with Charles Todd second from right.

Obtaining sources of power was a problem for the early settlers. The First Fleet brought just seven horses and seven cattle so, in the first few years, all the pulling, hauling and timber-sawing was done by humans. Even in 1839, while Mr W. Cooper’s Brisbane Steam Mill did most of the flour-milling in Sydney, there was also a treadmill or ‘discipline mill’—a form of hard labour for convicts. Still, human labour had been replaced for most things by then.

Harnessing steam power

The first steam engine in Australia drove a flour mill, which was set up at Sydney’s Cockle Bay (now Darling Harbour) in 1815. Owned by John Dickson—whose name lives on, although misspelt, in Dixon Street in Sydney’s Chinatown—the mill could grind 10 bushels (272 kilograms) of wheat in an hour. The Sydney Gazette praised it because, unlike windmills, a steam mill could operate whenever it was needed.

During the 1820s, a number of steam engineers arrived in Australia. They usually came when somebody ordered a new steam engine from Britain. Each new owner imported one, or even two, engineers—two was better, just in case one got sick or died. Once they had completed their contracts, the engineers would look around for other work in the colony.

A stationary steam engine pulling a plough towards it across a paddock in the 1880s.

Stationary engines

Many country museums today have at least one ‘stationary’ steam engine. Some of these engines could actually move around slowly, using steam power, while others were towed to where they were needed. They were used to operate sawmills, pull ploughs or run the machines in a shearing shed.

Engineer Daniel Matthew was brought to Australia to set up merchant John Raine’s Darling Mill at Parramatta in 1826, close to George Howell’s watermill. Both these mills made flour, but the choice of power depended on what was available. Horse, bullock, wind, human, steam and water power were all possible. People chose the most practical form of power available, and steam was not always the best answer.

Daniel Matthew built a sawmill near the northern Sydney suburb of Pymble in 1827 and, even though he was a steam engineer, he used bullocks to power his sawmill to cut locally felled hardwood timber. This mill drove the saw teeth at around 95 miles (150 kilometres) per hour and it could cut 450 feet (140 metres) of floorboards in an hour. When Matthew offered the mill for sale in 1848, he said it could be run by either eight horses or eight pairs of bullocks.

Matthew’s sawmill was a bit of a ‘fossil’, as forward-thinking people had moved on to doing everything by steam. In 1840, a long essay in The Sydney Morning Herald discussed using steam engines to irrigate farms. A 10-horsepower engine, working ten hours a day, could raise enough water some 40 feet (12 metres) to irrigate 60 acres (24 hectares) of crops. When it was not pumping, the engine could be used to power a flourmill, a sawmill or a machine that threshed wheat (separating the grains from the stalks).

Knowledge of steam engines had also spread out into country areas, as steam engines were simple enough for most practical men to operate, and even to maintain and repair—in fact, in Adelaide, which was founded less than seven years earlier, young George Wyatt made a steam engine called Cyclops in 1843.

Although knowledge of steam engines was becoming common, it was not universal. For example, a Cornish mining engineer named John Phillips offered a quartz crusher for sale in 1855. He lived in Castlemaine in Victoria and he knew the goldfields well, so he chose horses to drive the crusher. He had made it very simple so that ‘the roughest hand of a carpenter and blacksmith could repair any part of it’.

As far back as 1844, Australian newspapers wrote about a new invention called the ‘ignition engine’. This was probably one of the earliest references to the internal combustion engine that runs most vehicles today, but the first patents were still 15 years away.

In the cities, until electricity took over, many factories had a boiler-house where a steam engine drove a long shaft that machines could draw power from. That was the way things were done in the 1800s.

Knowledge of steam engines had also spread out into country areas, as steam engines were simple enough for most practical men to operate, and even to maintain and repair—in fact, in Adelaide, which was founded less than seven years earlier, young George Wyatt made a steam engine called Cyclops in 1843.

Transport

Sailing ships

Until the 1850s, only sailing ships came to Australia. A steamship named the Sophia Jane arrived from England in 1831, but she was an auxiliary steamer which meant that she only used her engines when the wind was in the wrong direction. In the early days, no ship could carry enough fuel to steam all the way to Australia, but later engines got better and ships got bigger.

Sailing ships could not go anywhere without wind and, if the wind blew in the wrong direction, they had trouble going against it. In open water, a ship could tack, zigzagging its way against the wind. This was a slow way to get to where you wanted to go.

Sailing ships’ times were unpredictable. In the Tamar River in Tasmania or at Port Adelaide in South Australia, wind from the wrong direction could stop ships putting out to sea for weeks and weeks. The Brisbane River in Queensland twists and turns all over the place so, whatever direction the wind went, it always blew a ship backwards, somewhere on the river.

In a narrow river, ships cannot tack, so some of the earliest steamers in Australian waters were steam-tugs that were used to haul sailing ships in and out of ports. Out at sea, ships could tack, but they could still be slowed down by headwinds.

Steamships

The first ship to steam from Europe to Australia was the P&O mail ship Chusan. It carried 40 passengers and took 80 days to get here in 1852. Sailing ships carrying the mail took about 120 days.

Steamships could keep to a timetable. However, the design of sailing ships also improved and, in 1859, the clipper Lightning sailed from Melbourne to Liverpool in 63 days. In that year, the P&O shipping company signed a contract to deliver mail between Britain and Australia in 55 days.

By the 1880s, the Murray River was a busy waterway.

Before that, smaller steamers had worked along parts of the Australian coast. Most people travelled from Sydney to Newcastle and Maitland in the Hunter Valley by steamer. Steamers also went to Morpeth (also in the Hunter Valley) where, for a short while, they were met by the horse-boat Experiment, which began operating in 1832. This flat-bottomed river boat was powered by horses driving the paddlewheels by walking on a treadmill. Experiment took goods and passengers up into shallow waters.

Experiment was towed to Sydney in 1833 and worked as a Parramatta ferry, but later the horses were replaced by a steam engine. By 1843, a steamer service connected Geelong, in Victoria, to Melbourne every day, and there were more steamers trading along the coast.

In the nineteenth century, people went from colony to colony by steamer. These were slow journeys, but they were more comfortable and faster than travelling by road.

Road travel improved when Cobb & Co started a coach service. They used American ‘Concord’ coaches, which had leather straps instead of iron springs. This gave a softer, rolling ride, but it made some passengers seasick! Pulled by eight horses, the coaches often carried as many as 40 or 50 passengers, with 12 to 18 people inside and many more outside.

An uncomfortable journey

German adventurer Friedrich Gerstäcker went from Sydney to Albury by mail cart in 1851. He then paddled a dugout canoe to a place near Echuca, where the canoe sank. Next, Gerstäcker walked most of the way to Adelaide, before riding in a cart on what he said was called the ‘nut-cracker road’ because, when a traveller with a nut in his pocket arrived at his destination, he would find that the nut had cracked. He also said that the passengers on that rough road did not speak for fear of biting their tongues!

With good horses and on a good road, coaches could reach around 12 miles (20 kilometres) per hour, but they often stopped to change horses and for passengers to take ‘comfort’ breaks, so coaches usually averaged only about 8 miles (13 kilometres) per hour. The coastal steamer made quicker progress and it was more comfortable, as long as you did not get seasick—but then that could happen on a coach as well!

On land, the horse was the main form of transport. In 1860, Australia had around 430,000 horses and, by 1900, there were about 1.6 million, with one horse for every two people. Horses pulled trams, omnibuses, carts, drays, ploughs, lawnmowers—almost anything that moved. However, over time they were replaced.

The rise of the railway

South Australia had a railway near the mouth of the Murray River in 1854. Horses pulled the wagons until steam took over in 1856. Victoria opened a short railway between Flinders Street Station and Port Melbourne in 1854 and, in 1855, Sydney opened a railway line to Parramatta that was 13 miles (21 kilometres) long.

The other colonies built railways a little later, but these small beginnings prepared the way for Federation in 1901, because train lines would spread and make travel between the colonies faster and easier.

Some people reacted in odd ways to railways, according to Sydney solicitor Maurice Reynolds. The Commissioner for Railways, Captain Martindale, apparently worried that trains would disturb cattle and annoy sheep. Worse, Morris Pell, the University of Sydney’s Professor of Mathematics, recommended high train fares because ‘otherwise every man, woman, and child would lose all their time and money running up and down the line continually’.

There would have been little chance of that, even in 1859, because just two morning trains arrived in Sydney, one at 8.30 and one at 9.30, while the afternoon trains left Sydney at 4.30 and 5.45.

By 1872, railways reached out into rural areas, rushing fresh food to the city and fresh news to the country, thus bringing the nation together. And sick people in the bush could now travel more easily to the cities for treatment.

More unusual forms of transport

Out in the pioneering districts, other forms of transport were popular. It would have been a lot harder to build the Overland Telegraph and the Trans-Australian Railway without the help of the Afghans—who actually came from Pakistan—and the camels they managed and taught others how to use.

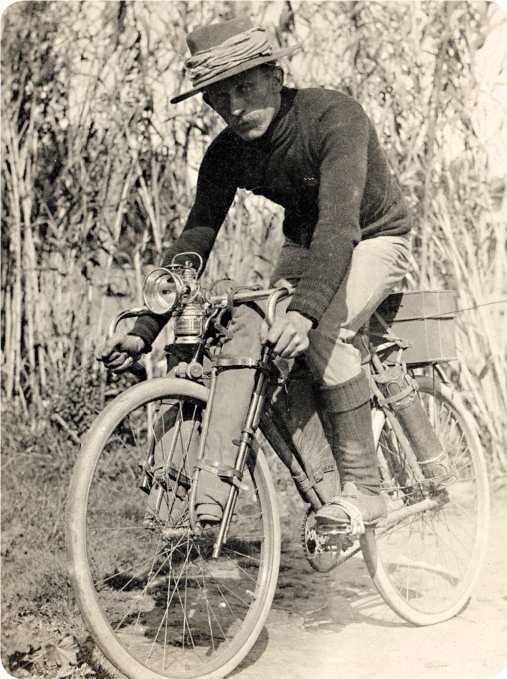

In the early 1900s, Francis Birtles, perhaps our last explorer, travelled around Australia by bicycle.

However, camels were slow and needed feeding so, on the eastern goldfields of Western Australia, bicycle messengers earned good money carrying telegrams out from Coolgardie. Except where the ground was sandy, hundreds of camel feet had made a firm, flat track, and so cyclists could easily cover 100 miles (160 kilometres) in a day. The cyclists travelled light, relying on the people to whom they took messages to provide them with food and a bed for the night.

In the early 1900s, Francis Birtles crossed the Nullarbor Plain on a bicycle because he was surveying the ‘road’ for the first crossing by car, which he made soon after.

Paddle-steamers

Spare a thought, though, for the people who made paddle-steamer traffic possible on the Murray, Darling and Murrumbidgee rivers. One of these intrepid explorers was Friedrich Gerstäcker, who went down the Murray River in a dugout canoe.

Another was an American named Augustus Baker Peirce, who took a 15-foot (5-metre) boat from Albury in New South Wales to Goolwa in South Australia, accompanied by a man who was a dancing master and fiddler, and an Aboriginal boy. They carefully mapped every feature on the river for paddle-steamer captains. Peirce marked dangerous snags and rocks with painted symbols on riverside trees, adding depth markers in a few places. He then made a continuous map ‘nearly an eighth of a mile long’ (200 metres). Copies were placed on rollers under glass on the paddle-steamers for the skippers to use.

One way or another, Australians were finding it easier to get around.

Electrification

Arc lighting

In late 1858, the world’s first electric lighthouse was built in England. There were no light bulbs then, so the light came from a giant electric spark called an ‘arc’. Wires were attached to two pieces of carbon that were kept a specific distance apart, and electricity came to the wires from a generator powered by a steam engine.

In June 1863, ‘electric light’ shone over Sydney. It was part of the ‘illuminations’ provided to celebrate the wedding of Edward, Prince of Wales, to Alexandra, which had happened three months earlier in England. The light came from two arc lamps on Observatory Hill—one red, the other white.

These sorts of lights were not suitable for homes, partly because the light was too bright, but also because the power source consisted of 100 large ‘voltaic cells’, or batteries. Three things were needed to provide electricity to homes: a way of generating and delivering electricity; meters to measure the amount of electricity people used so they could pay for it; and a safe, gentle light source. Until then, people mainly used gaslights or candles.

In 1879, the site of the new Garden Palace in Sydney’s Botanic Gardens had no gas supply, so the building work was completed in just eight months by workmen using arc lights until midnight each night. With no generators, the electricity again came from a large collection of batteries.

Balls, parties and other social functions in the country were often held at full moon, so people could drive home by moonlight. However, there were kerosene or gas lamps in some streets in towns and cities to help people find their way around at night.

There would be no electric cables until there were generators to feed them, and no generators until there were wires to carry the electricity, so how could electrification begin?

Turning on the lights

Electrification began with electric street lights. In 1888, Tamworth in New South Wales lit its streets with newly invented light globes, plus arc lights powered by a local generator. It claimed to have ‘outstripped all competitors in the race for colonial progress’.

In Tasmania, Launceston used hydro-electric power from the nearby South Esk River in 1895. Before long, a few households started to use electric current. Because electrification was used only in small areas, it could happen almost anywhere, even in outback areas—even out beyond the ‘black stump’!

Thomas Carrington’s 1882 illustration of some of the ways to use electric lights.

Powerhouse

By coincidence, the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, which is built around the Ultimo Power Station that used to power Sydney’s electric tram system, holds the parts of the Garden Palace exhibits which survived when the ornate palace in Sydney’s Botanic Gardens, which the workmen had built using arc lights, mysteriously burnt down in 1882.

Balls, parties and other social functions in the country were often held at full moon, so people could drive home by moonlight. However, there were kerosene or gas lamps in some streets in towns and cities to help people find their way around at night.

About 300 kilometres east of where explorers Burke and Wills died is the Queensland town of Thargomindah. It lies in dry country, and water was hauled into the town from Bourke, in New South Wales, in old ships’ water tanks until a bore found water at a depth of 800 metres.

In 1893 or 1894, a Thargomindah sawmill owner set up a steam-powered generator, which the local council bought in 1898. Two tenders were submitted to operate the generator. The cheaper tender came from a local blacksmith, who mounted a waterwheel in a casing made from an old water tank.

A waterwheel may seem unlikely in flat, dry country, but Thargomindah’s bore delivered hot water under such high pressure that, uncontrolled, the water spouted more than 20 metres into the air, and this pressure was enough to spin the wheel and generate electricity.

Powering the nation

By 1906, Australia had 46 power stations generating 23,000 kilowatts for domestic and industrial use. While dedicated generators delivered another 13,000 kilowatts for powering electric trams, electric trains were still years away.

In Sydney, the Ultimo Power Station was built in 1899 to power Sydney’s electric trams. It is now the site of the Powerhouse Museum. By 1901, all six capitals of the new states had electric trams, and only Sydney and Hobart had no electric street lights.

By 1927, a third of Australian homes had electricity, with lighting and electric irons using most of the current. Later, home appliances such as radios, toasters, electric jugs, power tools and radiators increased the demand for electricity.

Large authorities were formed in each state to manage the electricity supply. Rather than set up more inefficient, small generators, these operators installed very large generators near the coalfields, with wires carrying high voltages across the country. The Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme began in 1949 and was completed in 1972, but ‘Snowy hydro-electricity’ has never kept up with Australia’s needs.

An electric tram in Perth in the 1890s, with a cowcatcher to protect pedestrians.

The era of steam-driven power shafts, which ran through the centre of factories, was at an end.

The world’s first feature film

In the 1890s and 1900s, a stage play called The Kelly Gang toured Australia and New Zealand, where it was very popular. This play was probably one of the inspirations for the world’s first feature-length film, The Story of the Kelly Gang, which was made in Australia in 1906.

The film was shown just 26 years after the death of Australia’s ‘last bushranger’, Ned Kelly. Kelly’s mother and brother Jim were still alive when the film was released. Created by theatre-owners the Taits, the 60-minute-long silent movie was filmed largely at the Chartersville estate at Heidelberg, which is now a suburb of Melbourne.

An image of Ned Kelly in his armour, probably from the 1906 movie The Story of the Kelly Gang.

The Story of the Kelly Gang was very much a family affair. John and Nevin Tait wrote the script, their brother Charles directed the film, and Lizzie Tait was a stunt double. John and Nevin produced the film in association with William Gibson and Millard Johnson.

‘The longest film ever made’

Bailed up!

It is claimed that The Story of the Kelly Gang inspired five children in Ballarat in Victoria to break into a photography studio and steal money. The children then bailed up a group of schoolchildren at gunpoint. No wonder that, in 1912, the Victorian Chief Secretary banned the film from being shown in towns, including Benalla and Wangaratta, that had a strong connection with the Kelly family.

The Story of the Kelly Gang opened in Melbourne on 26 December 1906. It was shown there for seven weeks, before going on a long and very successful national tour. In 1907, it was screened in New Zealand and England, where it was billed as ‘the longest film ever made’. The film, which cost £1,000 to make, apparently made its producers £25,000—a very large sum in those days.

The film itself was silent, but a ‘lecturer’ explained what was happening while the film was being shown, and there were sound effects from behind the screen, including gunshots and hoof beats. Apparently, these were so loud at one screening that a film reviewer complained about the ‘Kelly Bellowgraph’!

The Kelly gang

From the fragments of film that have survived and from a copy of the program, we know that the film tells the story of the Kelly gang and its various run-ins with the police. The film ends with an image of Ned in full homemade armour, including his now iconic helmet, being repeatedly shot at by the police as he staggers towards them, guns blazing.

The film was criticised at the time by some politicians and policemen for ‘glorifying criminals’. The producers also had to apologise to the public for a ‘lack of authenticity’ in the film, because it showed policemen wearing their blue uniforms in the bush—which they would not usually have done. However, such ‘artistic licence’ was necessary in the film so that viewers could tell who was who.

At that time, Australia might have gone on to develop a thriving film industry, but the pressure from overseas film distributors was too great.