An invitation for important citizens to meet the Duke and Duchess of York.

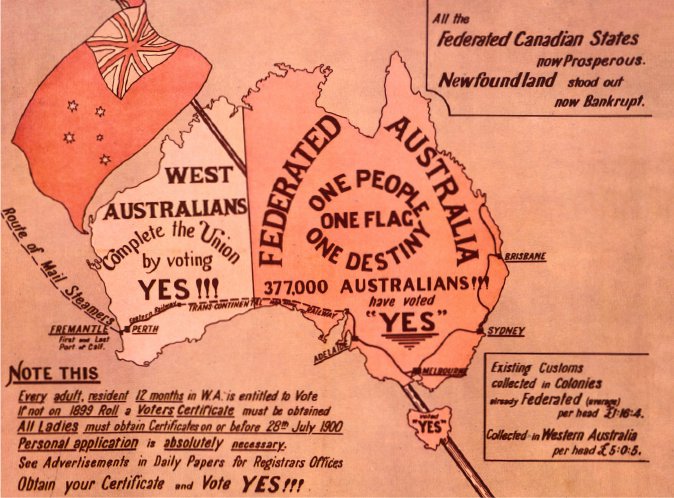

By 1901, Australia was ready to federate, and so six squabbling colonies united to make one nation. While most Australians had a real sense of being part of a single nation, some politicians feared losing their power and influence. Petty rivalries between sectional interests sometimes got in the way of the national interest. Issues like the site of the national capital, customs duties, subsidies, social welfare and immigration often divided the new nation.

An invitation for important citizens to meet the Duke and Duchess of York.

Painter Tom Roberts captured the moment when the Duke of Cornwall and York, later King George V, declared open the first Federal Parliament, in Melbourne, on 9 May 1901.

Moving towards Federation

The idea of a single Australian nation had been around for a long time before Federation. When Edward Trickett became the world sculling champion in 1876, Australian newspapers called him ‘the Australian Trickett’. They called a cricket match in March 1877 between an All-England team and a group of Victorian and New South Wales players ‘Australia v. England’ or ‘The International Cricket Match’.

Irish-Australian politician Charles Gavan Duffy was already talking about an Australian Federation in 1857. By 1877, Perth was connected by telegraph lines to the other capital cities and, during the 1880s, all the mainland colonial capitals except Perth were close to being connected by rail as well. In 1871, six out of ten white Australians had been born in Australia and, by 1888, it was seven out of ten people.

For and against

In 1883, Sir Samuel Griffith, the Queensland Premier, proposed a ‘Federal Council of Australasia’. This was not achieved, but at least it got people thinking. However, a number of politicians disliked the idea of a federation, perhaps because they could see no personal benefit in it. New South Wales never joined the council, and South Australia joined but later dropped out.

In 1889, Sir Henry Parkes, the Premier of New South Wales and a supporter of Federation since the 1850s, stopped at Tenterfield in northern New South Wales while riding the first train on a new line from Brisbane. He delivered what is now called the ‘Tenterfield Address’, calling for a conference to make Federation happen.

That conference was held in 1890. It achieved one significant thing: the Australasian Federation Convention of 1891. The convention had seven delegates from each colony and three from New Zealand. New Zealand later withdrew for a number of reasons, including the geographical distance between the two countries and the fear that the New Zealand Maoris would not be well treated in a federation with Australia. This was based on the way Australia treated Aboriginal and other non-European people at that time.

The parliament of Britain—ironically the only nation without a written constitution— passed the act that introduced the Australian Constitution.

When Parkes proposed a common navy and army for Australia and used the phrase ‘one nation, one destiny’, the other colonies finally came into line. This did not happen without the work of many dedicated people. For example, George Reid, premier from 1894 to 1899, was nicknamed ‘Yes-No Reid’ because of his balanced position on Federation, but he was instrumental in bringing New South Wales on board.

Alfred Deakin, who would later be one of Australia’s prime ministers, was a very active supporter and promoter of Federation. His hard work helped to secure the series of miracles that made it happen.

Developing a constitution

All nations except one have a written constitution. The exception is Great Britain, which instead has a very large collection of traditions and legal decisions. An independent Australia needed a constitution to set down who could legally do what, how and when.

One of the earliest and best-known written constitutions had emerged in 1787, after the USA had declared independence from Britain 11 years earlier. France adopted a constitution in 1791. The Australasian Federation Convention examined the Swiss and Canadian constitutions, and it also looked closely at the US constitution, but every part of the new document had to satisfy everyone.

The constitution also had to set rules for dealing with new inventions, thus providing rules for changing the rules. For example, the list of powers given to the Commonwealth in the Australian Constitution included section 51(v), which referred to ‘postal, telegraphic, telephonic, and other like services’. There was no radio or television in the 1890s, but this proviso in the Constitution allowed the High Court of Australia to look at the situation later and decide that ‘other like services’ included radio and television.

Tasmanian Andrew Inglis Clark, Queenslander Samuel Griffith and others looked at the Senate representation and then argued for the US model, in which each state had the same number of senators. That meant the smaller states could not be dominated by the larger ones. The main work on the proposed constitution was done during the three sittings of the second convention in 1897–98, in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne.

The first referendum on the new constitution was passed in 1898 in New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, while Western Australia and Queensland did not vote. The New South Wales majority was narrow. It was not enough, because a rule had been brought in that at least 80,000 people had to vote ‘yes’.

A second referendum in 1899 was passed in every colony except Western Australia, which still did not vote because Premier Sir John Forrest was still a ‘reluctant Federalist’. He had attended every convention held during the 1890s, each time arguing for greater concessions for Western Australia. He was keen to ensure that his state was not disadvantaged in any way.

Then the goldminers of the eastern goldfields in Western Australia threatened to form a new colony called Auralia that would join the Commonwealth. The British Government told Forrest this would be approved unless he held a vote. Forrest knew there were very few women on the goldfields, where he presumed that everyone would vote ‘yes’. To influence the poll, he gave women the vote, hoping that people in areas other than the goldfields, especially women, would vote ‘no’. He was wrong.

The parliament of Britain—ironically the only nation without a written constitution—passed the act that introduced the Australian Constitution. It was written by Australians, with Britain trying to ‘water it down’, but because Australia moved peacefully to independence, that is how it was done. The bill for the Constitution was passed on 5 July 1900 and the Western Australian ‘yes’ vote took place on 31 July 1900. That is why, in the first few lines of the preamble of the Constitution of Australia, there is no mention of Western Australia.

Pressure was placed on Western Australians to vote ‘yes’.

Forming a federal government

There was one final step: the creation of a government to run the first elections. The new Governor-General of Australia, Lord Hopetoun, had to choose one of the colonial premiers to form a government. Hopetoun had been ill, which may explain why he agreed that Sir William Lyne of New South Wales, as premier of the senior colony, should get the job of selecting a cabinet.

Alfred Deakin of Victoria called Lyne ‘a crude, sleek, suspicious, blundering, short-sighted, backblocks politician’! Everybody else refused to serve under him, as they knew that Lyne was a strong opponent of Federation.

And so it was that Edmund Barton took the job and became Australia’s first Prime Minister on 1 January 1901. He did not win a majority in the elections in March 1901 but, with the support of the Australian Labor Party, he remained Prime Minister until 1903.

Australia had become a nation.

Celebrating the new nation

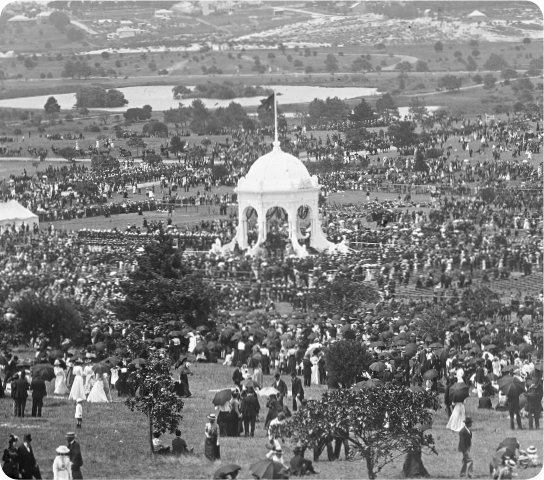

The Commonwealth of Australia began with a proclamation from Governor-General Lord Hopetoun on 1 January 1901—the first day of the twentieth century. The ceremony that made Australia an independent nation was enacted in Sydney’s Centennial Park.

There was a grand parade featuring decorated floats, soldiers and marching bands. Eight days of official and unofficial celebrations followed, with church services, military displays, sporting carnivals, concerts, banquets, fireworks and illuminations.

Recording the event

Before 1901, many other nations had begun with a ceremony, and many more have done so since, but Australia was well placed for a ‘first’—the recording of the opening ceremony using a recent invention, the movie camera.

Movies were so new that, when the plan was mentioned in September 1900, the film was referred to in The Sydney Morning Herald as a ‘living picture’. By 1901, there was just one well-known Australian expert in making ‘living pictures’—Captain Joseph Perry of the Salvation Army’s Limelight Department—so he was given the task.

There was a grand parade featuring decorated floats, soldiers and marching bands. Eight days of official and unofficial celebrations followed, with church services, military displays, sporting carnivals, concerts, banquets, fireworks and illuminations.

Perry built high timber platforms at five vantage points and mounted a fixed camera on each one. On the day, Perry rushed from camera to camera on a horse-drawn fire-engine. Afterwards, footage from just three of the five cameras was used to make a 30-minute film, which had its premiere in Sydney on 19 January 1901.

Unfortunately, the premiere was not a grand celebration of the emergence of a triumphant new nation. The film was sandwiched between Professor Godfrey’s ‘Wonderful Troupe of Trained Dogs and Monkeys’, a ballet, patriotic songs and a pantomime called Australis that offered views of Sydney in the far future.

The nation of Australia had been born, and there were ‘living pictures’ to prove it.

Crowds of people celebrating the beginning of their new nation in Centennial Park, Sydney.

The first Federal Parliament

The Sydney–Melbourne rivalry continued. Australia may have been proclaimed in Sydney but, until a national capital was built, it was agreed that Federal Parliament would meet in Melbourne. The leading citizens of Melbourne were determined to outshine Sydney when the first Federal Parliament met in their city.

Queen Victoria still ruled when the proclamation was read, but she died on 22 January 1901. The Queen’s grandson, the Duke of York, was asked to open parliament. By the time parliament opened on 9 May, he was the heir apparent, as his father was now King Edward VII. The Duke of York later became King George V. Now Melbourne could really shine!

Opening celebrations

In 1901, it took a lot longer to travel to Australia than it does now, so the sovereign’s son was the best royal representative Australia could hope for, and so the Duke of York opened parliament. When the sovereign is not available, the Governor-General opens parliament because he or she represents the sovereign. In 1954, 1974, 1977 and 1988, Queen Elizabeth II was able to come to Australia to open parliament.

Between March and July 1900, Britain’s Colonial Office fought hard to have the Australian Parliament made answerable to the British Parliament, with Britain controlling Australia’s foreign policy. The four representatives of Australia’s colonies— Edmund Barton, Alfred Deakin, James Dickson and Charles Kingston—successfully defended Australia against this attack.

Fighting for independence

Some people in Britain did not like Australia being an independent country and making its own decisions. In 1908, Prime Minister Alfred Deakin invited the American ‘Great White Fleet’—a naval battle fleet that was circumnavigating the world—to visit Australia. British politician Winston Churchill tried very hard to have the visit blocked. Luckily, he was unsuccessful, and Britain did not formally object.

The result was that the future king opened an independent nation’s parliament. However, the celebrations were muted because most people were still in mourning for Queen Victoria.

Representatives of other nations came to the party. A fleet of British, American, German, Russian and Dutch warships was anchored in Port Phillip Bay. Foreign consuls, army and navy officers in uniforms with gold braid added some colour, and so did judges and church dignitaries dressed in their robes. Three of the Labor representatives chose to wear ordinary suits and ‘boxer hats’, making a small statement about ‘equality’.

The opening ceremony finished with the stirring sounds of the Hallelujah Chorus to general cheers, as ladies stood on chairs and waved their handkerchiefs.

The Duke and Duchess of York drove past the cheering crowds, who were sitting on rough wooden seats, for which they had each paid 5 to 40 shillings. The royal couple drove through decorated streets to the Exhibition Building, which had the only hall large enough to hold all 12,000 guests. The senators-elect were in their seats and, at noon, the Duke of York arrived. The Usher of the Black Rod—the Senate official who keeps order in the Parliament—then brought in the members-elect of the House of Representatives.

First, Letters Patent were read out. This document from King Edward authorised his son to open the Parliament. Then the Duke made a short speech declaring the Australian Parliament open, after which he withdrew to a fanfare of trumpets. The Governor-General then administered the Oath of Allegiance to each member.

Now they were real members and not just members-elect. The senators and representatives went off in coaches to meet at Victoria’s Parliament House to elect a President of the Senate and a Speaker of the House of Representatives. The opening ceremony finished with the stirring sounds of the Hallelujah Chorus to general cheers, as ladies stood on chairs and waved their handkerchiefs.

The deed was done, and Australia was now an independent nation with its own parliament.

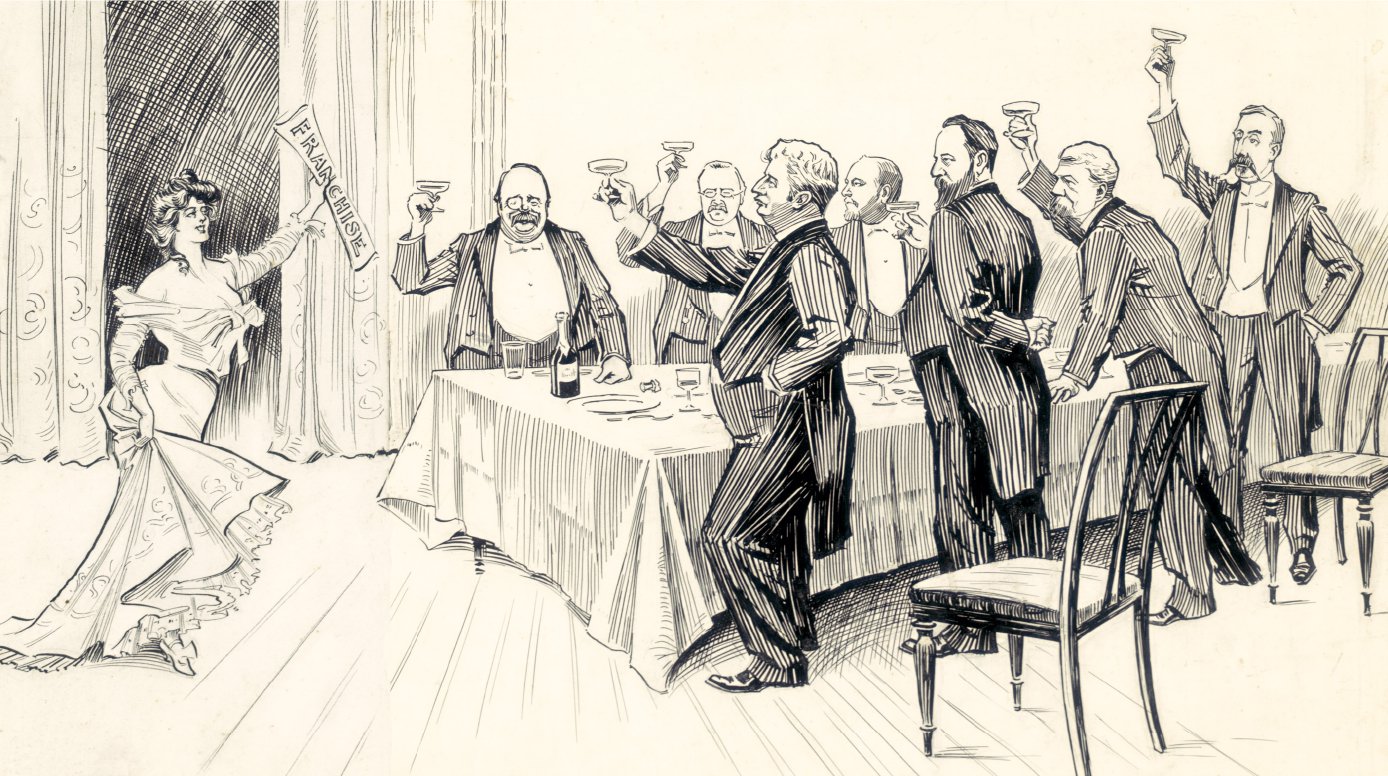

As responsible government came to the older colonies in the 1850s, the principle of ‘one man, one vote’ was seen as fair and reasonable. Unfortunately, it only applied to men— but giving women the vote was really just a matter of time.

Australian women, especially in rural areas, had to be tough. Most of them had large families, they often managed without servants, and even simple everyday chores like washing and cleaning were physically hard and time consuming.

Many poor women were left at home for months while their husbands went shearing or droving to make money. Even educated women had to get their hands dirty, digging gardens, chopping wood, hauling water, and caring for their children and their farms. In the cities, conditions were not much better.

South Australia leads the way

Australian women lived in a country that valued democracy and championed democratic rights, and so their struggle to get the vote was in some ways easier than it was for women in Britain, America and other parts of the world.

Australian suffragettes—women who actively campaigned for women to have the vote—used mainly persuasion, not demonstrations, to win their democratic rights. However, there were arguments and delays.

Newspapers reported on ‘women’s suffrage’ from about 1868 onwards, but it was not until the 1890s that women got the vote. The South Australian Government was the first in Australia, and the second in the world after New Zealand, to give women the right to vote.

Even in South Australia, the Adult Suffrage Bill failed in 1893, but it passed successfully a year later after the Legislative Assembly was bombarded with petitions from women supporting the bill. The new law was passed in 1894, and women in South Australia voted for the first time in 1896. It was another milestone for democracy in Australia.

The South Australian bill was a first in another way, by allowing women to stand for election. Catherine Spence stood for a place as a delegate to the Australasian Federation Convention in 1897. She was not selected, but at least she was able to try.

Women were also missing out in Western Australia, where they had been able to vote in local council elections since 1876, but they lost the vote when Western Australia became self-governing in 1890. A bill to give women the vote in 1893 was opposed by the Premier, Sir John Forrest, who said that the proper place for a woman was ‘to look after her home and not be running all over the place’.

A cartoon celebrating women gaining the vote.

Forrest gave women the vote before the constitutional referendum in 1900, but only because the eastern goldfields were very strongly in favour of a ‘yes’ vote, and he hoped that women would vote ‘no’ in the referendum. Forrest was wrong, but he did not dare to take away the right of women to vote once he had given it to them.

Who could vote?

Before Federation in 1901, women could vote in South Australia and Western Australia, while in the rest of Australia all male British subjects—including Aboriginal men—could vote. The 1902 Commonwealth Franchise Act gave women the vote throughout Australia but, at the same time, it took the vote away from Aboriginal people, with some complicated rules for those who were already registered to vote in the states.

The clause, labelled ‘Disqualification of coloured races’ said:

No aboriginal native of Australia, Asia, Africa or the Islands of the Pacific except New Zealand shall be entitled to have his name placed on an Electoral Roll unless so entitled under section forty-one of the Constitution.

Apart from that restriction, all British citizens could vote if they had lived in Australia for six months and had their names on the electoral roll, and if they were ‘not under twenty-one years of age whether male or female, married or unmarried’.

In 1902, New South Wales also gave the vote to women over 21, and the other colonies slowly came into line. It took even longer for women to be allowed to stand for a Commonwealth election, and it was 1943 before the first woman, Dame Enid Lyons, was elected to the House of Representatives.

In contrast, it took Great Britain until 1918 to give all men the vote, and even longer to give it to women. Australia was, indeed, a democratic country.

Enid Lyons, the first female member of parliament.

What’s in a name?

The word ‘Kanaka’ is now often regarded as offensive in Australian English. In Hawaiian, it means ‘man’, but in Australia it was used to refer to any Pacific Islander working in Australia. Most were Melanesian, some were Polynesian, and the more acceptable term today is ‘South Sea Islander’.

Restricting immigration

When Salvation Army Captain Joseph Perry’s film of the inauguration of Federation was shown, together with dogs, monkeys, a ballet and a pantomime, there was one item on the bill that would be considered offensive today: ‘Dainty Irene Franklin in her Charming Coon Songs’. In those days ‘coon’ was a term used to describe an African-American or, by extension, any dark-skinned person.

This reflected the attitude of white Australians to other races in 1901, when The Bulletin newspaper had the slogan ‘Australia for the White Man’. However, while many workers feared losing their jobs to cheap labour from overseas, others were worried that foreign workers would be exploited and abused—and with good reason.

Exploiting foreign workers

In December 1837, 42 ‘hill coolies’ from India landed in Sydney. Two months later, 15 of them escaped from their employers and headed for the Blue Mountains. They were arrested near Wentworth Falls, taken to Sydney and charged with ‘absconding’—running away.

The Indian workers had signed an agreement to work for five years, but they said they had not been given enough food or clothing and had not been paid. The contractor, a Mr Mackay, said that their pay was being used, under their contract, to pay for their fares to Australia. Before they arrived, Mackay had wrongly asserted that Indians ate the beef that Europeans refused to eat, only ate once every 24 hours, and wore little clothing.

The evidence in court showed that the Indians were being treated cruelly, but Mackay was never charged. In other words, those people were treated little better than slaves.

In 1852, the citizens of the New South Wales town of Goulburn learned that 30 Chinese labourers were being made to walk from Sydney to Wagga Wagga. One man, who had a scalded foot, had been chained to a dray, dragged along and beaten. Their only food was about one cup of flour a day—far less than the standard issue for bush workers. Angry local residents complained, but they got little justice for the men.

It was clear that foreign workers were regarded as cheap labour. At the end of the nineteenth century, Chinese shearers were often used as strike breakers. No wonder some Australian workers thought that foreign workers were ‘bad news’.

The Kanakas

By the late nineteenth century, Pacific Islanders, known as Kanakas, were being brought to Australia. While many came as indentured labourers on contracts, some were brought to Australia by ‘blackbirders’—men who kidnapped people from the Pacific Islands to use as labourers in other countries. They were often brought to Australia to cut sugarcane on the Queensland cane fields. This was hot, dirty work, and the canegrowers claimed that it was ‘not suitable work for a white man’.

Sugarcane had traditionally been cut by slaves because it was very hard work. After slaves in the USA were freed, they worked for wages in cotton fields, but many refused to cut cane and so America stopped growing sugarcane. In Fiji, Mauritius and the British Caribbean islands, Chinese and Indian labourers were brought in under contract, while Argentina imported Italian workers to cut cane.

People from the New Hebrides on their way to Queensland to cut sugarcane in the 1890s.

Some employers made good money from exploiting the Kanakas who came to work on contract in Queensland. Their contracts included payment for them to be taken home again at the end of the job, but some of them decided to stay.

However, while many workers feared losing their jobs to cheap labour from overseas, others were worried that foreign workers would be exploited and abused—and with good reason.

Some concerned citizens campaigned against the ‘Kanaka trade’, describing it as ‘disguised slavery’. It is difficult to know now what was true and what was propaganda. It was certainly not always an easy issue, and many people in other parts of Australia joined together to stop these foreigners from ‘flooding Australia’.

Chinese carpenters

Woodworking tools are the same the world over and so, when the gold ran out, many Chinese gold diggers turned to making furniture. At times, they dominated the trade. Some people claimed that the workers were ‘sweated’—overworked and underpaid—but there was no real evidence of this.

The furniture was well made, so the Chinese workers were seen as a threat to other woodworkers. In the late nineteenth century, laws required Chinese-made and ‘part-Chinese-made’ furniture to carry a stamp stating this. Some manufacturers went further, adding stamps stating that no Chinese labour had been used in the manufacture of their furniture.

Introducing the ‘White Australia Policy’

This racial attitude shaped some of the negotiations about Federation. Section 51(xxvi) of the Australian Constitution originally gave the Commonwealth powers to make laws regarding the ‘people of any race, other than the aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws’. The part regarding ‘aboriginal race’ was repealed in 1967.

Under that power, Federal Parliament passed the Immigration Restriction Act 1901. The main effect of the Act was to control further entry into Australia by certain races. For example, under the Act, Chinese-Australian import-export businesses could bring in Chinese workers to replace staff who died or left, but furniture factories could not.

The Act also brought in a dictation test, which involved having a new arrival write down a passage of 50 words or more in any European language that the testing officer chose. This meant it could be in a language which the migrant was not familiar with. Officially, there never actually was a ‘White Australia Policy’. However, the dictation test was usually applied by officers who knew what was expected of them.

The dictation test was abolished in 1958. The ‘nonexistent’ White Australia Policy largely faded away after that.

Providing social welfare

Advertisements for old age pensions appeared in Australian newspapers in 1856, but they were actually what are called ‘deferred annuities’—people bought an insurance policy that would give them a weekly payment (an annuity) until they died.

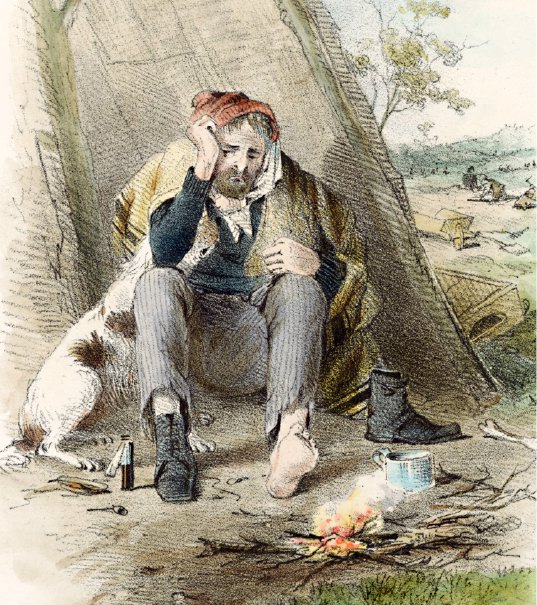

Such pensions were fine for those who had the money to pay for the insurance, but this was not the case for people who were old, too worn-out to work and had no money. In Britain, even in the twentieth century, paupers were often put in a workhouse for the poor and left to die, but democratic Australia had no workhouses.

Sick or injured people often died before help arrived.

In 1891 and 1892, Europeans were talking about introducing old age pensions, and people in Australia and New Zealand were interested in the idea. In 1893, women in New Zealand had the vote, and people predicted that there would also be old age pensions there before long.

Social conditions were changing in Australia. The economic depression of the 1890s meant there were fewer jobs and more poor people. But, public health services were getting better and so people were living longer. This created a growing demand for pensions. Between 1891 and 1901, the number of Australians aged over 65 increased by about 60 per cent.

Magistrates and state politicians threatened to take away the pensions of any pensioner who got drunk, but even a harshly controlled pension was better than no pension at all.

Introducing pensions

In 1896, a parliamentary select committee in New South Wales recommended the introduction of an old age pension, but with a number of restrictions. However, nothing came of it.

In January 1898, a South Australian delegate at the Australasian Federation Convention suggested giving the Commonwealth the power to pay age and invalid pensions. This was voted against, but it was later included as section 51(xxiii) of the Australian Constitution.

In 1898, New Zealand introduced a pension. In September 1899, in New South Wales, William Lyne replaced Sir George Reid as Premier. Reid had already promised to bring in old age pensions, and Lyne said he would do the same, but the bill to make this law did not come before the New South Wales Parliament until November 1900. The new Act came into force on 1 January 1901, with the first payments made in July.

Victoria’s Act was passed in the last days of 1900 and, on 5 January 1901, Victorian newspapers told would-be pensioners how to apply for a pension. The rate was the same as in New South Wales, but only a few Victorians received the full amount. The Queensland Government brought in a pension soon after that, but at a lower rate of payment than in New South Wales.

A poetic ending

Australian nurse and poet Jennings Carmichael lived in poverty in a workhouse in England with her sons, after her husband deserted them. After she died of pneumonia in 1904, an appeal was launched by admirers of her poetry to bring her boys back to Australia, where they were looked after in private homes.

Magistrates and state politicians threatened to take away the pensions of any pensioner who got drunk, but even a harshly controlled pension was better than no pension at all.

During the parliamentary debates, the opponents of pensions had argued that the pension was going to be a Commonwealth responsibility, but this showed that the opponents did not quite understand how the new Constitution worked. In areas where the Commonwealth had the power to do something, the states could still make laws, but section 109 of the Constitution said that, where state and Commonwealth laws disagreed, Commonwealth law overruled state law.

On 10 May 1901, the first full day of federal parliamentary sittings, a Tasmanian member of parliament, King O’Malley, gave notice of a motion that would start the process to create national old age and invalid pensions. The laws were passed in June 1908, but pensions were only paid from July 1909 (old age) and December 1910 (invalid). A Commonwealth maternity allowance also began in 1912.

Australia had really started to look after its people.

Life was hard for many old people, even in the early twentieth century.

Formulating the Australian Constitution was always a matter of compromise. After 60 years of sniping and squabbling, neither Sydney nor Melbourne would let the other be the national capital, so yet another compromise was needed. That is why section 125 of the Constitution reads:

The seat of Government … shall be within territory which shall have been granted to or acquired by the Commonwealth … in the State of New South Wales … distant not less than one hundred miles from Sydney.

‘Seat of government’ means capital city, and there was nothing to say it could not be a lot further from Sydney than a hundred miles. Many country towns and districts could see the excellent business prospects of having the capital city nearby.

Behind the scenes, Victorian politicians were trying to get a national capital as close as possible to Melbourne, while New South Wales politicians wanted it to be as close as possible to Sydney.

Possible sites

The President of the New South Wales Land Appeal Court, Alexander Oliver, was appointed in October 1899 to assess the different possibilities. Offers poured in from Queanbeyan, Yass, Corowa, Albury, Nowra, the Dorrigo plateau, Orange, Bathurst, Armidale, Tumut, Delegate, Young, Bombala and Eden. Six months into his work, Oliver said he would select six sites and recommend three.

In October 1900, Oliver explained that the capital city might have a population of 40,000. Based on figures he had gathered from the USA’s capital city, Washington DC, those people would probably need 150 gallons (about 700 litres) of water each day. Just three rivers could reliably deliver that much water— the Murray, the Murrumbidgee and the Snowy—as all received snowmelt water each spring. However, he thought the area around Orange might also be suitable.

Later, Oliver recommended that a choice be made between sites near Eden-Bombala, Yass and Orange. He added that the southern Monaro, the region near Yass and where Canberra is now, was the best choice. The politicians started to argue about it, and a Royal Commission in 1903 recommended Albury or Tumut.

District Surveyor Charles Scrivener reported on the options and recommended Dalgety, about 22 miles (35 kilometres) from Jindabyne. In August 1904, the Seat of Government Act named Dalgety as the site for the federal capital.

A 1909 map of a proposed site for Australia’s capital, complete with ornamental lake.

Behind the scenes, Victorian politicians were trying to get a national capital as close as possible to Melbourne, while New South Wales politicians wanted it to be as close as possible to Sydney. In the end, the New South Wales Government would have to agree to release the land, so New South Wales had an effective veto.

Choosing Canberra

By 1908, the choice was between Dalgety and Canberra. The supporters of Canberra called Dalgety ‘blizzard-swept’. They were in a slight minority in the House of Representatives, but the Senate appeared to favour the Canberra site. There were, however, nine other sites still in the ballot on 6 October—Albury, Armidale, Bombala, Orange, Lyndhurst, Lake George, Tooma, Tumut and ‘Yass-Canberra’. Three of the 11 choices were close to where Canberra is today.

A 1910 photograph including four of the surveyors who planned the site for the capital.

In the final round of voting, the votes in the House of Representatives showed that the smaller states were worried about being dominated by New South Wales. A month later, the Senate was deadlocked at 18-all between Tumut—which never got more than four votes out of 72 in the House of Representatives—and Yass-Canberra, until a Victorian senator switched his vote to support Yass-Canberra. The bill was passed, assented to, and the Yass-Canberra area was chosen.

Capital names

There must have been sighs of relief as Lady Denman, the wife of the Governor-General, revealed that the name of Australia’s new capital city was ‘Canberra’. Suggestions had come in from near and far for names for the new capital. They ranged from the interesting—Shakespeare, Myola, Austral City—to the bizarre— Eucalypta, Kangaremu, Eros, Thirstyville and Cookaburra. And then there was Sydmeladperbrisho, which was obviously designed to try to keep all the states happy!

‘Yass-Canberra’ was between Yass, Lake George, the current site of Canberra and the Murrumbidgee River. As one newspaper noted, Yass-Canberra was a district, not a site for a capital city. When surveyor Charles Scrivener examined the area in 1909, he recommended the Canberra valley as the best city site, partly because the Molonglo River could be dammed, making an ornamental lake, and also because it had a good water supply from the Cotter River. That recommendation was accepted.

The Federal Capital Territory was created on 1 January 1911, on the nation’s tenth birthday. At the end of April 1911, a competition was launched to design the new capital. In May 1912, the design presented by American architect Walter Burley Griffin and his wife Marian Mahony Griffin was named the winner.

In February 1913, the Minister for Home Affairs, King O’Malley, drove in the first survey peg. A month later, O’Malley, Attorney-General Billy Hughes and Prime Minister Andrew Fisher laid the foundation stones, and Lady Denman, the wife of the Governor-General, named the capital Canberra. It is said that nobody knew how to pronounce the name until she said it, but Canberra had been on the map for many years.

In 1927, the Federal Parliament moved to Canberra. The capital city was open for business.

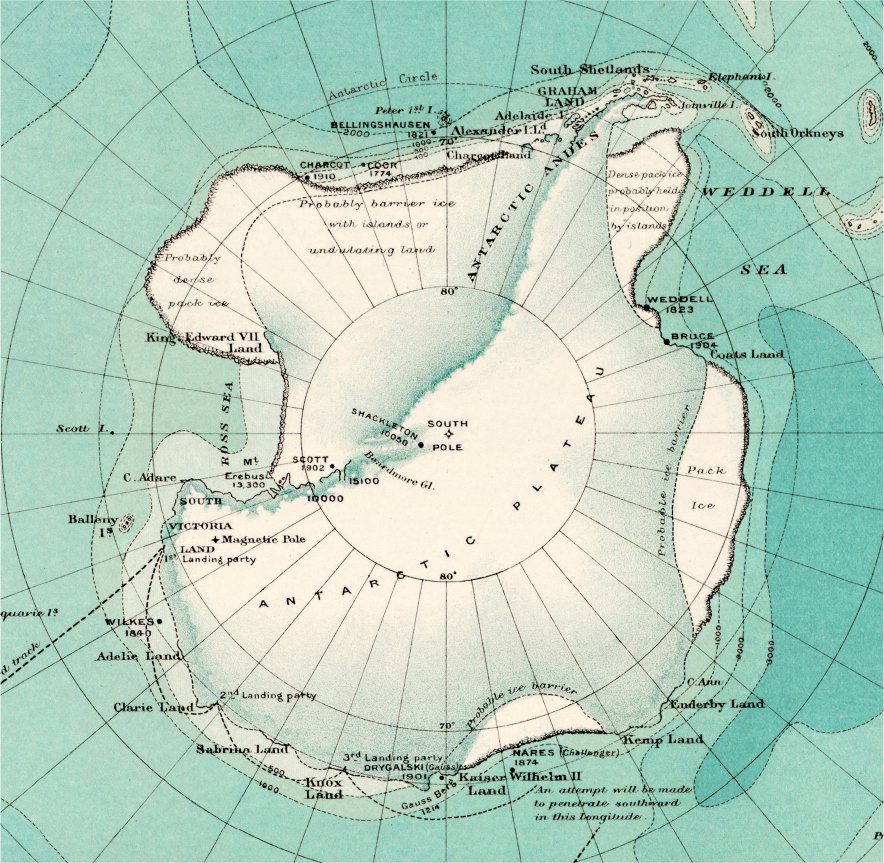

Travelling south with Mawson

Australia has strong links to Antarctic exploration. James Cook visited Australia’s east coast on his first voyage in 1769–70, but he explored southern waters in his next two voyages. James Weddell, Charles Wilkes and James Clark Ross—after whom the Weddell Sea, Wilkes Land and the Ross Sea in the Antarctic were named—all visited Australia.

These men usually visited the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, Sir John Franklin, before or after cruising in the Antarctic. Franklin was a famous polar explorer, who later died while searching for the Northwest Passage, north of Canada.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the mapping of Australia was almost complete, so anybody wanting to explore had to travel further south. And that is just what Douglas Mawson did.

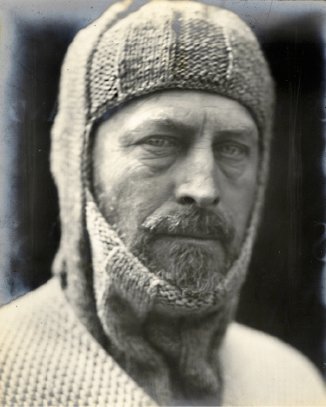

South with Shackleton

People speak of those who travelled with Mawson as ‘Mawson’s young men’. But Mawson himself was also a young man when he travelled south with British explorer Ernest Shackleton as a geologist in 1907 at the age of 25. And, when he led his own expedition in 1911, he was only 29.

Before he joined Shackleton’s expedition, Mawson had been appointed as a lecturer in geology at the University of Adelaide. He had discovered tillite—a rock made of glacial sediments—near Olary in South Australia and Broken Hill in New South Wales. That set him thinking about icy conditions, which is one of the reasons why he joined Shackleton’s expedition.

After the Shackleton trip, Mawson wanted to mount an Australian expedition, and so he helped to raise the large sum of £46,000 to fund it. That was a lot of money in those days—in comparison, the process of selecting the site for Australia’s national capital, which was described at the time as ‘a massive waste of money’, had cost £15,000.

Surviving Antarctica

Once they were ready, Mawson and his party of scientists sailed south. Then, using sledges pulled by husky dogs, they explored a lot of the ice. In December 1912, Mawson was out exploring with two other men, Belgrave Ninnis and Xavier Mertz, when Ninnis—along with his sledge, most of their food and some of their dogs— disappeared into a deep crack in the ice called a crevasse.

Mertz and Mawson were 300 miles (500 kilometres) from their base, with enough food for themselves and their dogs to last just 10 days. The travel time back to base was about a month. As each dog weakened, they killed it and ate it, but the liver of huskies is dangerously rich in vitamin A, and Mertz died—most probably of a vitamin A overdose.

Mawson struggled on, hoping to get close enough to the hut at Adelie Land so his body and papers might be found later. Luckily, he found a food store left by a search party, and so he made it back to the hut. There, he and six other men waited out the winter before being rescued in the spring. The rescue ship had actually left, believing that Mawson was lost in the snow, but a radio message soon cleared that up.

Australians were pleased that Mawson and his men had survived. As happened to heroes in those days, he was knighted, and so he became Sir Douglas Mawson. Mawson and his ‘young men’ performed important work in the areas of geology, biology, chemistry and physics. They extended our knowledge of Antarctica, that extreme and in many ways very non-Australian part of the world.

Mawson and his ‘young men’ performed important work in the areas of geology, biology, chemistry and physics.

After the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, Mawson returned to Britain, where he was born, and worked on high explosives and chemical warfare. And then, in 1929, Mawson led another group of young men south.

The tradition of Australian Antarctic research continues to this day.

A portrait of Sir Douglas Mawson, similar to the one on the $100 note.

A map of Antarctica.

Related newspaper articles of the time

An 1891 Victorian petition to grant women the vote.

Female suffrage edges closer in NSW, 1900.

An argument levelled at conservative women who feared being made to vote.

Carruthers' plan and promise in NSW on pensions

Albury's Expression of interest.

Bathurst's Expression of interest.

Bombala's Expression of interest.

Bombala and Delegate's Expression of interest.

Dorrigo and Young's Expression of interest.

Eden's Expression of interest.

Goulburn's Expression of interest.

Goulburn, Orange and Molong's Expression of interest.

Nowra's Expression of interest.

Nowra's Expression of interest.

Queanbeyan's Expression of interest.

Yass and Armidale's Expression of interest.

Governor-General to visit Canberra.

Explore more