The wonders of the ‘wireless’ brought radio sets powered by pedalling to remote homesteads.

In the 1920s, the Western world started to get back on its feet after years of war-time suffering. For many reasons, it was a different world to the one people knew in 1914. Women had been doing ‘men’s work’ on Australian farms since European settlement but, once the men went to war, women all over the world began working in offices and factories. It was also a much more connected world, with radio messages flashing around the world, and aircraft and motor cars linking distant places. Science and technology had taken off as well.

The wonders of the ‘wireless’ brought radio sets powered by pedalling to remote homesteads.

Australians took to the skies.

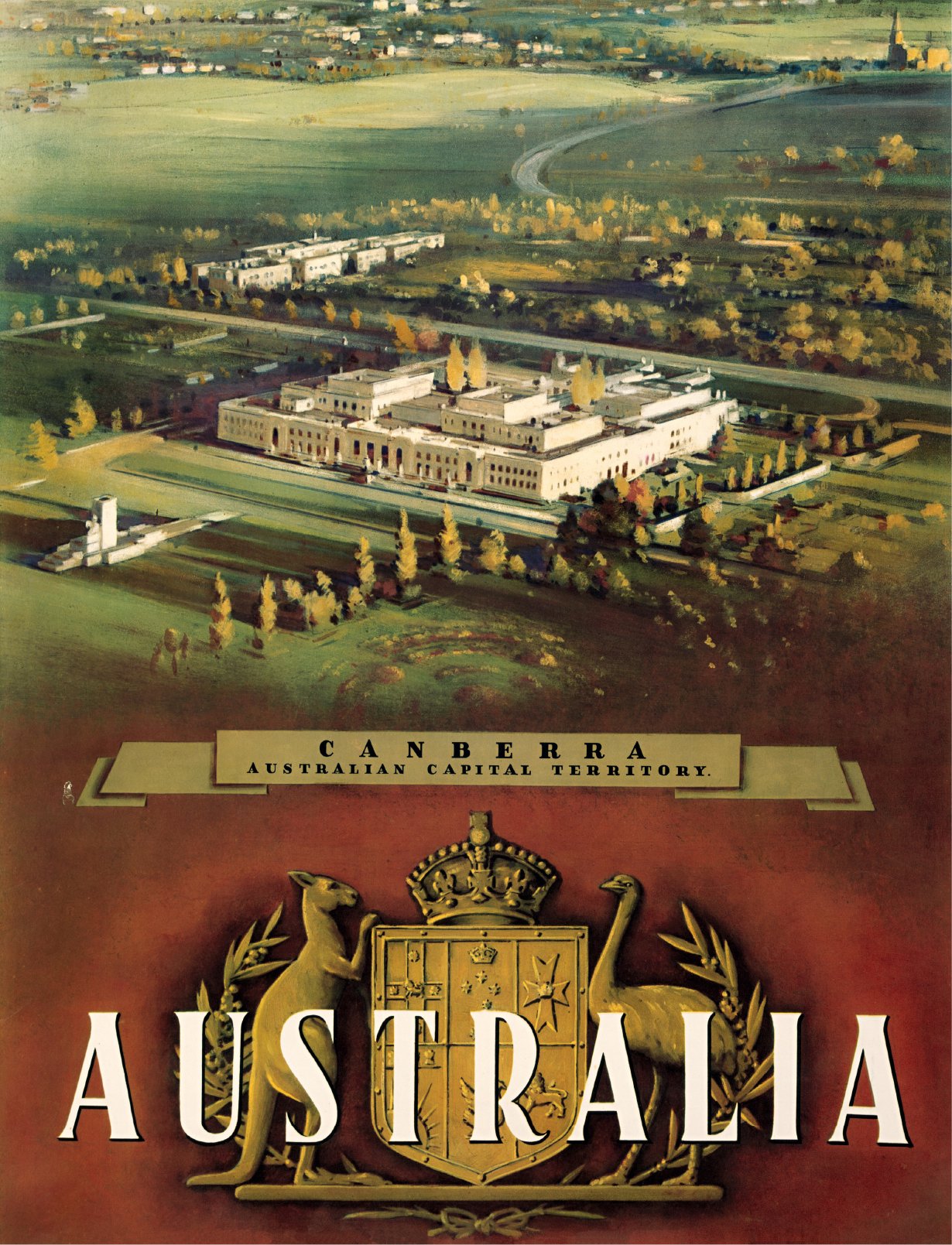

The 1920s saw the building of Australia’s own national capital, located between Sydney and Melbourne, the two biggest cities in the country.

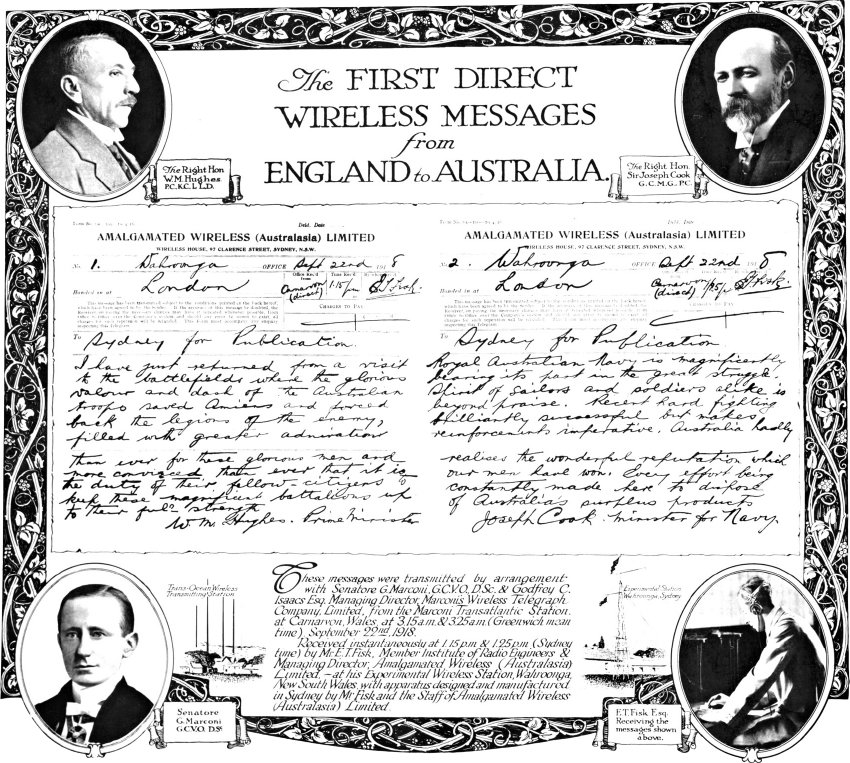

Around 1900, radio waves were called ‘Marconi waves’, after Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi, who worked out how to use them to send signals. The term ‘wireless telegraphy’ was then adopted because Morse signals were used as they were in a telegraph, but without wires. There were no voices, like on a telephone, just ‘dots’ and ‘dashes’.

The British army used radio signals in 1900 during the Boer War, and radio was first used in Australia to signal to ships at sea. That is why, when the Great War (World War I) broke out in August 1914, the Australian Government ordered all ‘wireless equipments’ to be dismantled and handed over to the navy.

Stars like singer Gladys Moncrieff known as ‘Our Glad’, could be heard on the ‘wireless’.

In 1932, Prime Minister Joseph Lyons started the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC), which was funded by the government and had no advertising.

Just a week after the Great War started, an officer raided premises in Melbourne and used wire cutters to destroy the large aerials—the long wires strung across high vantage points. Even radio receivers had to be handed in, in case spies found ways to use them.

Radio technology improved quickly. In September 1918, Australian businessman Ernest Fisk arranged for test transmissions to Australia from Prime Minister Billy Hughes, who was in Britain.

After the war, amateurs and those who had learned about wireless technology during the war started experimenting again. In September 1922, listeners in England heard a music concert from The Hague in The Netherlands. On 23 November 1923, Sydney radio station 2SB (later 2BL) broadcast the first music ever heard ‘over the air’ in Australia. Another Sydney station, 2FC, started two weeks later, and other radio stations soon followed around Australia.

Entertaining households

Until about 1939, the wireless used lots of stage and concert performers. Stage performers read scripted serials like Dad and Dave. This popular serial began in 1937 and was based on Steele Rudd’s On Our Selection, which was first published in 1899 in The Bulletin. Based on the story of a family living on the land, these entertaining serials celebrated Australianness.

Radios were huge, and owners had to buy expensive licences to use them.

Only a small number of performers could broadcast at one time, because they all had to stand very close to just one microphone. Families would also sit close to the wireless receiver in their lounge rooms at night to listen in.

In 1932, Prime Minister Joseph Lyons started the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC), which was funded by the government and had no advertising. The ABC took over existing radio stations, including 2FC and 2BL in Sydney. It started broadcasting on 1 July with 12 stations—two each in Sydney and Melbourne, one in each other state capital, and four regional stations. Originally, they all ran their own programs, but they were soon relaying programs by cable from one station to another (because only cable carried clear signals over long distances).

Synthetic cricket

In 1934, the ABC developed ‘synthetic cricket’. While it was possible to broadcast from England to Australia by ‘short wave’, the signals were often poor, so the ABC used coded telegrams to let commentators in Australia give a ball-by-ball description of the game over the radio. They used sound effects to simulate the sound of bat on ball or the applause of the crowd. Everybody knew they were simulations, but people still listened in all night, each night.

In 1918, the first direct wireless messages travelled from England to Australia. Unlike ‘cables’, messages reached their destination almost immediately.

By 1933, the ABC had created The Children’s Session, with its very popular Argonauts Club, which by 1950 had 50,000 dedicated and enthusiastic members. The program lasted until 1972.

The ABC also started broadcasting cricket matches, and it was immediately caught up in the controversy over the bodyline-bowling test cricket series that Australia played against the Marylebone Cricket Club (England) in 1932–33. The ABC commentary helped stir up Australian outrage at this sometimes dangerous variation on the game.

One important radio invention was the ‘pedal wireless’, which allowed people in remote parts of Australia to call the Flying Doctor in an emergency and to get education in remote areas through the School of the Air.

In many ways, access to the radio changed Australia forever.

Scientific advances

Breeding wheat

Englishman William Farrer came to Australia after contracting the lung disease tuberculosis (TB). Back then, people thought that Australia’s warm, dry climate was better for people who had TB. In Australia, Farrer worked as a surveyor, but then he became interested in breeding wheat that was resistant to ‘rust’ and other diseases that destroyed wheat crops.

In 1900, Farrer developed what was called ‘Federation wheat’. It resisted rust and gave a high yield. Three years later, enough seed had been produced to distribute to farmers. Over the next 20 years, Federation wheat trebled the Australian wheat harvest.

With that advance, and the massive increase in the size of the wool yield due to advances in sheep-breeding practices during the nineteenth century, many Australians were beginning to appreciate what science could do for them.

Groundbreaking research

In 1916, the Advisory Council of Science and Industry (ACSI) was set up in Australia as part of producing a national laboratory. Wartime developments in explosives, gas warfare, radio, submarine-detecting hydrophones and army tanks had demonstrated the importance of scientific research.

In May 1916, the ACSI advertised in the newspapers for a ‘Science Abstractor’. An abstractor read through the world’s scientific literature looking for reports that council researchers could use. Applicants needed to be able to read French and German, and the position was ‘open to women as well as men’. The world was definitely changing.

In 1920, the ACSI became the Commonwealth Institute of Science and Industry. Then, on 14 October 1926, the three members of the new Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) were announced. In November, the members of the state committees were named and, by March 1927, CSIR investigators were studying the underground grass grub, pea diseases, ‘sheep troubles’ and the shale-oil business. By July 1927, they were seeking ways to deal with salt blooms in irrigation areas.

Soon after, the CSIR played a part in using a moth from Argentina called Cactoblastis to control prickly pear—a noxious weed. The work was directed at agriculture, which was one of Australia’s main industries in the 1920s. The CSIR’s program expanded during the 1930s and 1940s, with plant and animal pests and diseases still the main concern of its scientists, and their attention also going to fuels, the cold storage of food and forestry.

A cartoon about prickly pear taking over the land.

The first prickly pear plant was brought into Australia on the First Fleet to breed the cochineal insects that lived on it. These insects produced a dye that was used to colour the red coats worn by British soldiers. By the 1920s, the prickly pear cactus had infested 60 million acres (about 24 million hectares) of land in New South Wales and Queensland. The CSIR’s Cactoblastis caterpillars were definitely needed to help wipe out this pest!

Researchers had been trying to control Australia’s rabbit plague for many years. They had thought about using chicken cholera to kill rabbits, but that scheme had been dropped because it was too dangerous.

During World War II, radar was important, so the CSIR hired physicists and technicians. After the war, as well as agriculture and forestry, efforts were concentrated on new scientific areas like building materials, atmospheric physics (weather), metallurgy and land resources.

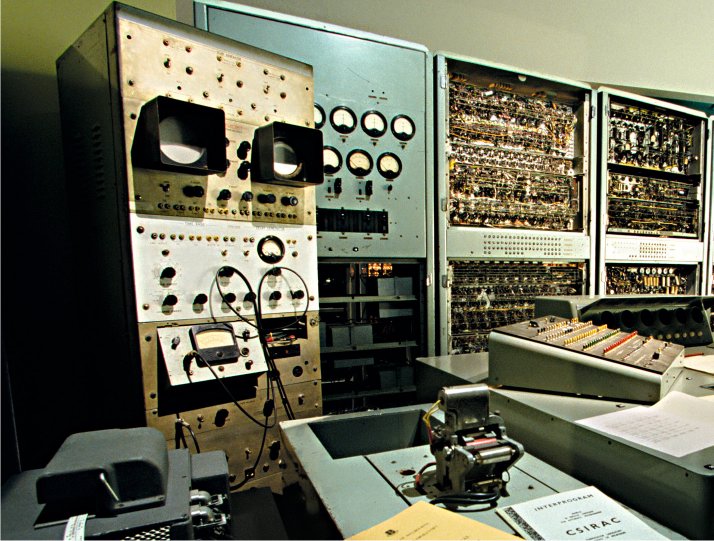

During the 1940s, the CSIR’s achievements included developing an insect-repellent, investigating cloud-seeding to produce rain, and building Australia’s first computer, CSIRAC. The CSIR became the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in 1949.

Researchers had been trying to control Australia’s rabbit plague for many years. They had thought about using chicken cholera to kill rabbits, but that scheme had been dropped because it was too dangerous. From 1919, people wondered whether a Brazilian rabbit disease called myxomatosis might reduce the number of rabbits (it did, for a while). In the last days of the CSIR, plans were put in place, and the first major achievement of the new CSIRO was the release of the myxoma virus in 1950.

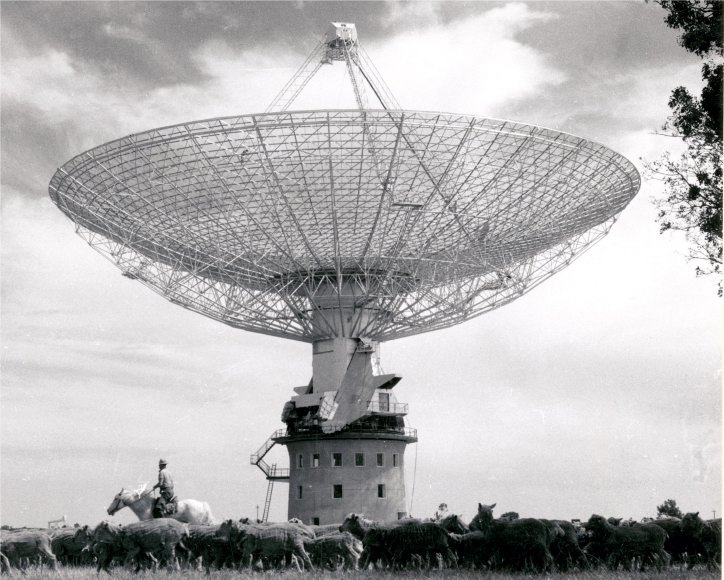

During the 1950s, Australia became a world leader in radio astronomy—a term coined by CSIRO scientist Joe Pawsey. The CSIRO also pioneered solar hot water; developed Siroset—a way of getting permanent creases in wool fabrics; built the Parkes radio telescope, better known as ‘the Dish’; and developed atomic absorption spectroscopy.

Since a movie was made about it in 2000, the Parkes radio telescope in New South Wales has been called ‘the Dish’.

In the 1960s, CSIRO researchers worked out how to wipe out a forest pest called the Sirex wasp. They also introduced dung beetles to control bushfly populations. The 1970s saw work on the greenhouse effect and climate change, and the Interscan aircraft landing system, while the 1980s brought polymer banknotes, the wireless internet and gene shears (a way of ‘snipping’ a gene out of a chromosome). Their important work continues.

One thing is certain: CSIRO research has helped to improve the quality of life in Australia and the world.

Australia’s first electronic computer, CSIRAC, was used by scientists from 1949 to 1964.

It took nine years, from 1899 to 1908, to choose a site for Australia’s new capital, and another four years to choose an architect and start a survey of the area. It was another 14 years before Canberra was established enough for at least some public servants to move there from other parts of Australia.

Accessing Canberra

In the 1920s, a telephone call from one capital city to another went from a local exchange to a ‘trunk line’, and then to an exchange near the person being called. Trunk calls were very expensive, and this made communicating with places like Canberra difficult. Airmail deliveries were rare, so mail communication was slow. All transport was slow as well, including air travel, which was also very expensive. This made getting to Canberra difficult.

Progress on the site itself was even slower. The main delay came from bureaucrats interfering with the plans of architect Walter Burley Griffin, and his wife and partner, Marion Mahony Griffin. By December 1913, the Griffins had amended their award-winning design slightly, but people were already questioning it. In July 1914, Walter Griffin said that the families of officials who were expected to live in the capital could start ‘packing their trunks’ in about three years time.

The Canberra Federal Capital of Australia Preliminary Plan.

At a royal commission in 1916, Walter Burley Griffin complained that protecting his reputation and position against attacks by ‘Federal officers’ had wasted nine-tenths of the time he had spent in Australia.

Bureaucratic wars

Then came two wars—the Great War and a bureaucratic war. The Town Planning Association of New South Wales called the bureaucratic war an ‘attempt to sidetrack the plan of Mr. Walter Burley Griffin and substitute the discredited departmental plan’.

The architects who created the plan—Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin.

This departmental plan was mainly the work of surveyor Charles Scrivener. Called The Design of the Layout of the Federal Capital City of Australia as Projected by the Departmental Board, the departmental plan was attached to the program for Canberra’s naming ceremony on 12 March 1913. The plan was a combination of some of the design entries, plus a few of the Departmental Board’s own ideas, and it was said to be cheaper. Luckily for Griffin’s vision, an election came soon after and the new government, led by Prime Minister Joseph Cook, dismissed the board. However, that did not bring an end to the fighting.

At a royal commission in 1916, Walter Burley Griffin complained that protecting his reputation and position against attacks by ‘Federal officers’ had wasted nine-tenths of the time he had spent in Australia. In late 1920, an advisory committee was appointed to supervise the work, but it contained some of the troublemakers. And so, in January 1921, Griffin walked away from the project. Earlier delays could be blamed on wartime problems, but those which came later were mainly caused by the committee’s decisions.

Providing a home for Federal Parliament

One of the major projects that did go ahead at this time was the building of what was called the Provisional Parliament House. This ‘temporary’ building, now known as Old Parliament House, housed Australia’s Federal parliaments from 1927 until 1988, when it was replaced by the present Parliament House.

The Provisional Parliament House was designed by the Commonwealth’s Chief Architect, John Smith Murdoch, and his advisers in a style known as ‘stripped classical’ or ‘modern renaissance’.

Building began in 1923, when a large group of tradesmen converged on Canberra to construct the parliament and other public buildings. They lived in tents, huts or cottages provided by the government. The building site was supplied with material by trains running on two railway tracks—one to Kingston Railway Station and the other to the Commonwealth Brickworks at Yarralumla.

Too many pies!

To celebrate the opening of Parliament House, an official lunch was held for the Duke and Duchess of York and other dignitaries. They dined on turtle soup, poached salmon and ‘Canberra pudding’. The large crowd outside was not forgotten, and they lunched on meat pies and scones. However, the organisers had over-catered, and so two truckloads of meat pies, sausage rolls, prawns and fish were later buried at the nearby Queanbeyan rubbish tip.

The grand opening of Parliament House was held on 9 May 1927. In preparation, fully grown trees were cut down from surrounding areas, carried to the site on horse-drawn wagons, and then planted to give the building an instant garden.

The flags of the United Kingdom and Australia hung side by side on the building, along with brightly coloured bunting. Royal Australian Air Force planes performed a flyover, although their timing was apparently a little out, and so they drowned out the sound of Dame Nellie Melba singing the national anthem, God Save the King. Sadly, one of the pilots died in an air crash later that day.

The Duke and Duchess of York arrived in an open carriage, and they were greeted by Prime Minister Stanley Bruce and other dignitaries, as well as by four-year-old Gwen Pinner, who presented the Duchess with a bouquet of flowers. Some 15,000 members of the public attended the celebrations, with many camping in tents or sleeping in their cars in the empty paddocks that surrounded the new building.

The Duke of York opened the doors of Parliament House with a key made of gold, and then presided over the first parliamentary sitting in the new Senate Chamber.

When the Great Depression hit in 1929, Canberra had a population of 7,000 people. Building work in the capital had stopped, but Federal Parliament now had a permanent home.

Motoring across Australia

Early attempts

In 1900, Herbert Thomson and E.L. Holmes had an incident-free drive from Bathurst to Melbourne in a Thomson steam car. They spent a total of 56 hours and 36 minutes on the road, at an average speed of about 14 kilometres per hour—about the same as a horse-drawn Cobb & Co coach. Back in Melbourne, Holmes commented that the rise of the motor car would surely lead to better roads—and it eventually did. The car could get faster, but the Cobb & Co coach could not.

In late 1901, a motor car made the trip from Sydney to Broken Hill, taking a month to get there. The longest day’s travel by car was 80 miles (130 kilometres) from Euston to Wentworth in south-western New South Wales. That took six hours, and the average speed was over 20 kilometres per hour.

Driving further and faster

The headstone on the grave of Francis Birtles at Waverley Cemetery in Sydney describes him as an ‘explorer and photographer’. After serving in the Boer War, Birtles returned to Australia and began adventuring. In 1907, he rode a bicycle from Sydney to Charters Towers, Darwin, Adelaide and Melbourne, and then back to Sydney.

Living off the land

Like the early explorers, Francis Birtles lived off the land on his journeys around Australia by bicycle and motor vehicle. His bicycle was fitted with a holster to carry his hunting rifle, and so on many of his trips he shot and ate rabbits. He even found them on the treeless Nullarbor Plain.

In 1908, Harry James and Charles Kellow completed a Sydney to Melbourne drive in a car in 25 hours and 40 minutes. Then, in 1909, Birtles rode his bicycle from Perth to Sydney to check if it was possible to drive a car across Australia. He decided to use a car with wooden axles so that when they broke—as they surely would—he could make new ones. He drove across the Nullarbor about four years later. Then, in 1917, Birtles, his brother Clive and historian M.H. Ellis drove from Brisbane to Sydney in 29 hours and 10 minutes. Cars were getting faster.

In the 1920s, the motor vehicle was still a luxury item, but as roads got better and time became more precious, people welcomed the independence that motor vehicles brought them. In country areas, the dray and the lorry pulled by horses were replaced by ‘motor lorries’—trucks. Crops and produce were soon taken to market on trucks, not trains.

There had been another development well before World War II—the invention of the ‘ute’, or utility vehicle.

Developing the Aussie ‘ute’

There had been another development well before World War II—the invention of the ute, or utility vehicle. The Ford Motor Company is said to have received a letter from a country woman in Gippsland, in Victoria. As the banks would lend money for farm vehicles but not for private vehicles, she asked:

Why don’t you build people like us a vehicle to go to church in on a Sunday, and which can carry our pigs to market on Mondays?

John Flynn (known as ‘Flynn of the Inland’) travelled the outback in northern Australia in a ute, often filled with passengers.

According to Ford, motoring engineer Lewis Bandt then designed a vehicle with a tray that could carry a 550-kilogram load, but also had a weatherproof cabin. It went on sale in 1934.

Others had already thought of such a design. The Willys Utility Truck was available in 1913, but it did not have a weatherproof cabin. And James Freeland Leacock had patented a similar design to Ford’s in 1930. However, it was the Ford utility truck, or ute, that was available for people to buy.

Cars for the masses

World War II was the first war in which armies did not rely mainly on horses. After 1945, ordinary people wanted motor vehicles, so a new mass market developed. It was a mass market that in many ways changed Australia.

On average, small towns had been settled around 60 miles (100 kilometres) apart. They needed to be close enough for farming families to get to them, do their shopping and get home, all in one day. Later, the introduction of motor vehicles meant that farmers could now drive past small towns to get to larger regional towns. A number of small towns lost shops, then banks, then the post office and the doctor, and soon some of those towns were no more.

In the cities, suburban areas had ‘corner shops’— family-run businesses that sold milk, bread and other essential food items. After the war, shopping centres and supermarkets were also established, and they forced many corner shops out of business. Many people now had refrigerators and freezers at home, so they could buy larger amounts of food. But that meant they needed a car to carry it home.

In the end, the motor vehicle significantly changed life as it had existed before World War II.

Many young Australian men had learned to fly aeroplanes during the Great War and, before long, some Australian women also learned those skills.

Australia is a land where distance can be the great enemy, but such distances can be overcome using aircraft. In 1859, Maurice Reynolds claimed that railways would make it possible for a city to have suburbs 100 kilometres from its centre, but people now realised that planes would make even the Australian outback more accessible.

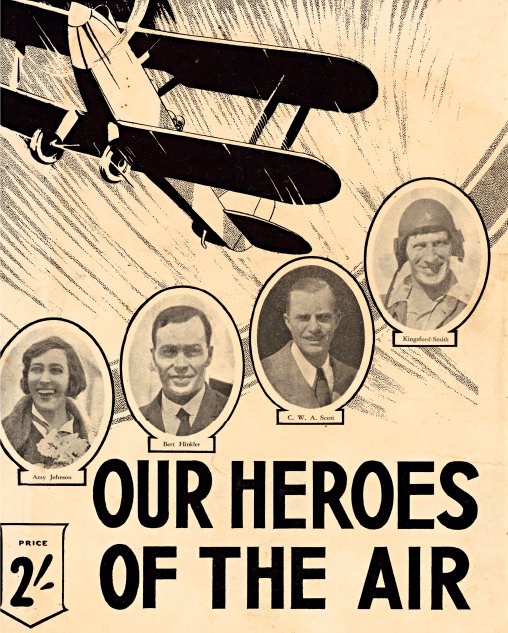

This song celebrated Amy Johnson, Bert Hinkler, C.W.A. Scott and Charles Kingsford Smith.

Nancy Bird went on to fly an air ambulance in outback New South Wales and to set up the Australian Women Pilots Association, while Lores Bonney flew solo from Brisbane to London in 1933.

Establishing Qantas

Paul McGinness and Hudson Fysh both transferred from Australian Light Horse regiments to the Australian Flying Corps. They flew together in No. 1 Squadron as pilot and observer. After the war, Fysh got his pilot’s wings, qualifying in February 1919.

In August and September of 1919, the two men surveyed part of an air race route from Katherine in the Northern Territory to Longreach in Queensland. They did this in a Model T Ford—the first mass-produced motor car.

McGinness and Fysh realised that air transport would be much quicker, so they started a company called Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services Ltd—QANTAS—in 1920.

Racing through the air

Prime Minister Billy Hughes had organised a prize of £10,000 (equal to about $2 million today) for the first Australians to fly in less than 30 days from England to Australia—around 8,400 miles (13,500 kilometres).

The winners of the race were brothers Captain Ross Smith of the Australian Flying Corps and Lieutenant Keith Smith of the Royal Air Force, along with two of their sergeants, Walter Shiers and James Bennett. The Smiths were knighted, and the sergeants were both made air force officers for their efforts.

Some other Australians missed out because the race was held under the rules of the Royal Aero Club in Britain. Aviator Bert Hinkler, who had been flying with the Royal Naval Air Service, wanted to fly in the race alone. The Aero Club decided that was unsafe.

Charles Kingsford Smith had a team of four, but they were not allowed to take part because none of them was a good enough navigator. Most pilots navigated by following roads, rivers or railway lines, but for travelling long distances, especially over the sea, somebody on the plane had to be able to navigate by taking sightings from the stars or the Sun.

The Smith brothers made it from London to Darwin on 10 December 1919, after flying for just over 27 days. One expert said that, if they used teams of crews and planes, the flight could be done in five days, but that never worked. Even in 1938, Dutch airline KLM took seven days to get from Sydney to Amsterdam.

Bert Hinkler resented missing out on the race. He bought an Avro Avian aeroplane and, in 1928, he flew the same route as the Smiths, reaching Darwin in just 15½ days, flying solo.

Flying into history

Australian Charles Kingsford Smith had flown with the British Royal Flying Corps and, like Hinkler, he wanted to set a record. He decided to fly a plane across the Pacific Ocean, so he teamed up with another Australian aviator, Charles Ulm.

Harry Lyon (navigator), Charles Ulm and Charles Kingsford Smith (aviators) and James Warner (radio operator) in front of Southern Cross, Los Angeles, California, 1928.

In an attempt to attract sponsors, they set a record for flying around Australia, taking 10 days and 5½ hours in 1927. The New South Wales Premier, Jack Lang, offered them £3,500 (equal to about $700,000 today) towards their trip across the Pacific.

Lang lost an election just after that and the sponsorship fell through, but Kingsford Smith and Ulm found another sponsor. They selected a ship’s captain to be their navigator, and took on a radio operator from Kansas in the USA. On 31 May 1928, ‘Smithy’ and his crew left Oakland near San Francisco in California in the three-engine Fokker the Southern Cross. They flew first to Hawaii, then Fiji, then Brisbane, making the trip in a flying time of just over 83 hours.

In October 1930, Smithy flew solo from London to Australia in 9 days and 22 hours and, in 1934, he and P.G. Taylor flew from Sydney to San Francisco. Then in 1935, Smithy and a copilot crashed in a storm over the Bay of Bengal. Parts of their plane were found, but there was no trace of either man.

Daring women pilots

By 1934, when another London to Melbourne air race was being planned, several women pilots were likely starters. Nineteen-year-old Nancy Bird (later Nancy Bird Walton) wanted to participate but, at that time, lacked the experience, and Lores Bonney (who preferred to be called Mrs Harry Bonney) had plenty of experience but did not have the right plane.

Nancy Bird went on to fly an air ambulance in outback New South Wales and to set up the Australian Women Pilots Association, while Lores Bonney flew solo from Brisbane to London in 1933.

One way and another, Australia produced some very resourceful pioneering aviators.

Family connections

Lores Bonney—who flew as ‘Mrs Harry Bonney’ because she wanted her husband’s name to live on after he died—was taken on her first flight by her cousin, aviator Bert Hinkler. He also bought her a plane. When she flew solo from Brisbane to London in 1933, she was photographed looking down her nose at something. She explained: ‘The man asked me where I was from, and I was thinking, “Don’t you know that VH on the fuselage means Australia?”’

Related newspaper articles of the time

In 1910, people had a very narrow view of what "wireless" might do.

Another 1910 vision of the future of "wireless".

The use of wireless by steamships, 1919.

The quality of jokes about "wireless" wasn't high in 1925.

The effect of radio ("wireless") on copyright owners.

Some people were not happy with the radio service they got.

Explore more