The news was grim, all over the world.

Through the 1920s, everything was going well, but the rich got greedy and the greedy got rich. People made the classic mistake of assuming prices would keep rising, but prices never do. Even before the Wall Street stock-market crash of 1929, the economies of the Western world were going sour. Wartime damage to economies, wartime debts, a welfare bill to care for widows and orphans, and the lack of fit working men all helped to make the inevitable Great Depression.

The news was grim, all over the world.

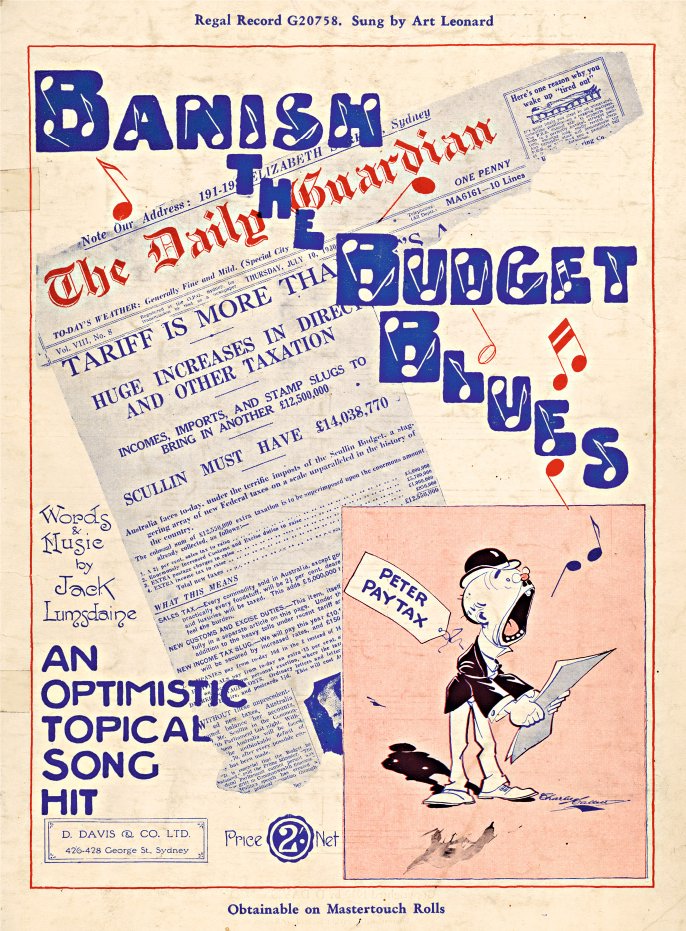

In much of Australia, men went ‘on the wallaby’ (wandering the bush) because they could not find work.

The opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 was a symbol of national hope.

Australia’s economy was at risk after the Great War. Some 60,000 young men had died and many Australians were unemployed. That caused unrest, and extremist groups formed. Their opponents called the left-wingers ‘Communists’, but they had no descriptive name for the right-wingers until later when they called them ‘Fascists’.

The extremists were mostly ex-servicemen who wanted somebody to blame for the state of the world and its economy. Nothing seemed to be getting better, so some people lost confidence in democracy and were attracted to more extreme views of the world.

People could cheer themselves up by buying this song as a gramophone record or as sheet music.

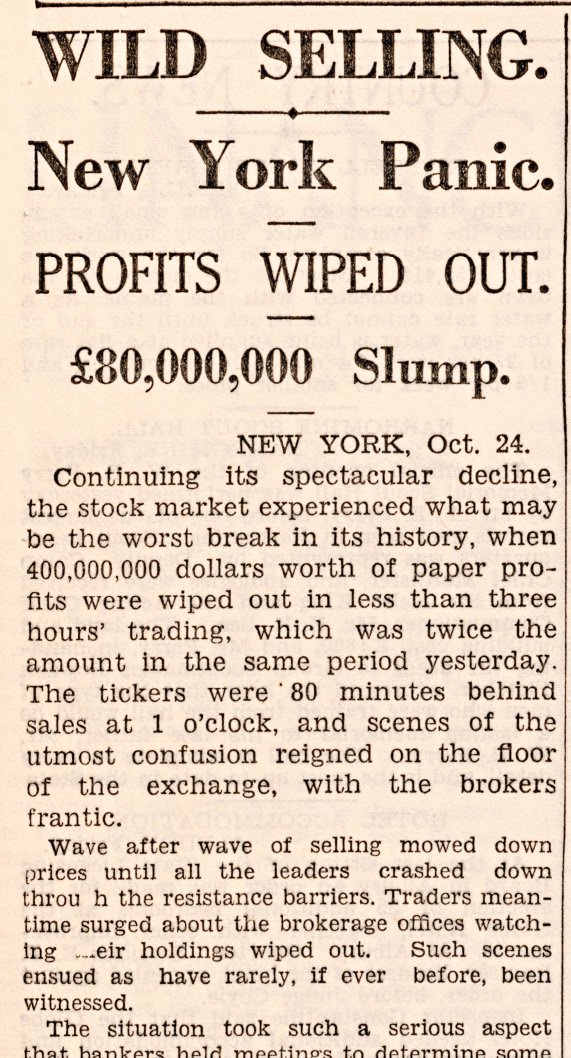

The markets crash

The Great Depression was triggered by a stock-market crash on Wall Street, the centre of stock-market trading in New York in the USA. Unemployment was already going up in Australia before 24 October 1929, when the US market dropped by 11 per cent in one day.

The depression in the USA spread across the world. When the stock market crashed, unemployment in Australia was already at around 10 per cent. By the middle of 1930, 21 per cent of the workforce was unemployed. By the middle of 1932, it was one-third. Things slowly got better, but some Australians remained out of work until 1939.

After the stock-market crash, the US Government needed money, so it asked Britain to pay its debts from the Great War. To raise money, the British Government then asked Australia to repay its loans. Some of those loans had funded Australia’s war effort—a war fought largely for the benefit of Britain. Other loans were the result of often irresponsible borrowing during the 1920s. Australia’s debts were so high that even paying the interest owed on them became difficult.

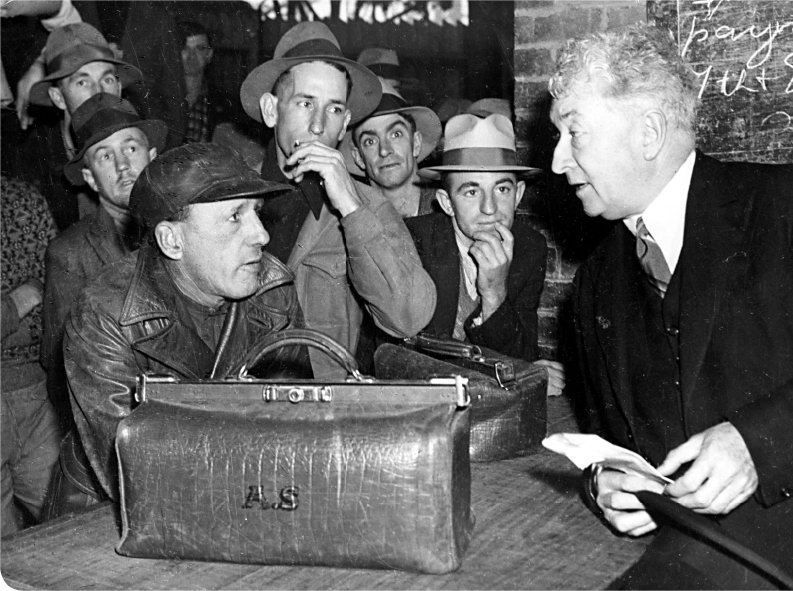

Niemeyer lays down the law

Australia wanted to delay paying Britain back for the war loans for the time being. On 14 July 1930, Otto Niemeyer of the Bank of England arrived in Australia. He had come to ‘examine’ Australia and its financial situation.

Niemeyer said Australia was overconfident and living beyond its means. He declared that Australia must accept a lower standard of living and do its duty as an obedient colony by supplying Britain with raw materials and goods, and buying British goods in return. He demanded that the Australian Government meet its loan obligations to Britain.

Niemeyer had supposedly been invited to Australia as an observer by Labor Prime Minister James Scullin, but that did not stop him commanding the state premiers to balance their budgets immediately. This caused a lot of argument.

The views of the conservative side of politics were summed up by Robert Menzies, a Victorian Nationalist politician, in an address on 3 May 1931 as part of the ‘A Pleasant Sunday Afternoon’ series of talks. He praised traditional British standards of honesty, justice, fair play and resolute endeavour, adding that, rather than give that away, ‘it would be better for Australia that every citizen within her boundaries should die of starvation’!

Joseph Lyons, who became Prime Minister in 1931.

Most of the premiers agreed with Menzies. On 25 May, they and the Commonwealth Government agreed to the ‘Premiers’ Plan’, which ordered higher taxes and a 20 per cent drop in government spending, including all wages, salaries, pensions and awards controlled by governments.

Prime Minister James Scullin and Treasurer Edward Theodore—who was known as ‘Red Ted’—wanted to print more money and spend it on public works to create jobs. The scheme put forward by Labor’s deputy leader, Joseph Lyons, was closer to the Premiers’ Plan.

By the middle of June 1931, the federal Labor government was falling apart due to arguments within its ranks. In the election on 19 December 1931, the United Australia Party—which later re-formed as the Liberal Party of Australia—won in a landslide, with former Labor deputy leader Joseph Lyons as prime minister. He had resigned from the Labor Party in March 1931.

One act in this drama was still to be played out. In New South Wales, Premier Jack Lang, a firm social reformer, would have nothing to do with a scheme that he thought deprived widows and orphans just to help rich English bondholders. Lang also wanted to reduce the interest on loans in Australia to a low 3 per cent.

The right-wing New Guard was plotting to depose Lang, the communists were making a noise, and Lang held the state’s Treasury, as cash, at the Trades Hall to stop the Commonwealth Government seizing it.

In the end, Governor of New South Wales Sir Philip Game dismissed Lang as premier, the opposition won the following New South Wales election, and austerity was enforced.

The Great Depression deepened.

Niemeyer said Australia was overconfident and living beyond its means.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge

Brisbane, Perth, Hobart and Sydney were all built beside bodies of water. In each case, that created problems as the small settlements became large cities. Sydney had the worst problems because the harbour, a drowned river valley, is shaped like a fern leaf..

At the end of the last ice age, the glaciers in the Northern Hemisphere melted, the melt-water ran into the oceans and sea levels rose. The ocean pushed up along river valleys and flooded across coastal plains, but it did not rise high enough to cover the tough sandstone ridges of Sydney. To cross the drowned river valley, Sydneysiders needed lots of bridges—even more than the other state capitals.

In 1815, Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s architect, Francis Greenway, suggested building a bridge from the south shore to the north shore of Sydney Harbour, but there was no real need for one then. Later, when all the good farmland at Parramatta had been taken up, a few people discovered that the sandstone ridges running north had small caps of shale that made the soil good enough for market gardens, and so settlements developed along what is now the North Shore railway line.

That railway line opened in 1890. As soon as it did, people began building houses along it. After 1893, they could catch a train to Milsons Point and cross the harbour by steam ferry. People began talking about having a harbour crossing.

In 1900, a group of politicians tried to get agreement to a proposal that the Duke of York would lay the foundation stone for a harbour crossing while he was visiting Sydney for the inauguration of Federation, but the proposal was not successful.

The talk in Sydney in 1900 was mainly about a railway bridge, high enough so that ships could go underneath it. A plan was in place by 1911, and John Bradfield was appointed chief engineer of the project in 1912. By 1916, his design was ready, but it was the middle of the Great War, so the work was delayed.

‘In the name of the loyal and decent citizens of New South Wales, I declare this bridge open!’

The Sydney Harbour Bridge was known as the ‘Iron Lung’ during the Great Depression, because it kept so many people in work. Its ‘curved’ arch is actually made from straight pieces of steel. It took nine years to build and cost over half a billion dollars in today’s money. The four pylons, which do not actually support the structure of the bridge, are covered in 40,000 pieces of granite from Moruya on the New South Wales South Coast. Almost six million rivets hold it together.

From 1900 on, motor cars, motor lorries and motor omnibuses had all become important forms of transport, as had trams. It was decided that the new bridge needed two train lines, two tram lines, and as many lanes for road traffic as possible. In the end, Bradfield allowed for what then seemed like the huge number of six traffic lanes!

Building begins

Parts of The Rocks area in Sydney had been torn down in the clean-up after the plague epidemic of 1900. Another 800 homes were demolished to make way for the bridge. However, between April 1923 and when the bridge opened in March 1932, its construction kept many Sydneysiders in work. During the Great Depression, a time of great misery for many people, the Sydney Harbour Bridge was a symbol of hope.

The two arms of the bridge’s arch began to move out over the water in March 1929, with an arm coming from each side of the harbour, reaching towards each other across the gap. Until the two sides met in August 1930, hidden cables stopped them from crashing down into the water.

While the bridge was being built, 16 workers were killed on the job or died later as a result of their injuries. The bridge was finally opened to great fanfare in March 1932, with a parade and much celebration.

A grand opening

The one event most people still know about from the day the bridge opened was completely unofficial.

Some conservative people were offended that Premier Jack Lang was opening the bridge rather than a member of Britain’s royal family or the king’s representative, New South Wales Governor Sir Philip Game. On 19 March 1932, as Premier Lang stepped forward to cut the ribbon, Captain Francis De Groot, a member of the right-wing New Guard, rode forward on horseback and slashed the ribbon with his sword, shouting: ‘In the name of the loyal and decent citizens of New South Wales, I declare this bridge open!’

De Groot was arrested, the severed ends of the ribbon were tied back together, and Lang performed the official opening ceremony.

Everyone who crossed the bridge on its opening day in 1932 received this special certificate.

When people are out of work and barely have enough money to buy basic food and clothing, paying the rent comes low on their list of priorities. During the Great Depression, landlords wanted to be paid first. When they were not paid, they evicted the tenants from their houses. In some cases, people banded together to fight the police who came to force the tenants out but, in the end, the tenants had to go—the landlords had the law on their side.

Those who were evicted accused the landlords of being greedy, and perhaps some of them were. However, some landlords were retired people who had put their savings into buying a house and so, when the rent was not paid, they did not have enough money for food or clothing.

Scraping a living

When money was tight, people often lived on bread and ‘dripping’—the animal fat that their grandparents had burnt in lamps. Others ate food like damper and ‘cocky’s joy’—golden syrup. Rabbits were also very welcome when they were available.

‘Roof rabbits’

During the Great Depression, people bought rabbits from the ‘rabbitohs’—street vendors. But they made sure the rabbitohs had skinned and dressed the rabbit carcasses with the paws still in place, because a cat without skin or paws looks very much like a rabbit, and nobody wanted to eat what they called ‘roof rabbit’!

Some people went fishing, while those with fruit trees in their backyards made sure none of the fruit was wasted. They would scrimp and save to buy enough sugar to make jam with the fallen fruit.

Sydney’s sandstone cliffs offered dry shelters that people could enclose, like this one at Kurnell.

In winter, those who were lucky enough to have a wood stove would burn anything they could find. People also put sheets of newspaper between their blankets and sheets to help them keep warm.

Young people left school as early as they could because it was easier for 14-year-olds to get jobs because they were paid less. Sadly, when they got older, they were sacked because they then cost too much.

On the wallaby track

Men trudged the city streets looking for work, but those who went ‘on the wallaby’ had it hardest of all. ‘On the wallaby’ probably originally meant living on wallaby stew, but it came to mean walking ‘on the wallaby track’—the faint paths made by animals hopping through the bush. These men went from farm to farm, hoping to get work, or at least a feed.

In country areas, food was easier to get, even if money was short, so country people did not usually go hungry. However, when they went to the dentist or the doctor they had to pay with eggs or a leg of lamb.

In the cities, some out-of-work and homeless people moved into caves, or nearby bush or paddocks, where they set up tents or rough huts made from any building materials they could find.

Men headed for farming areas, hoping to get work, if only to earn their ‘tucker’.

Others fished for their supper.

A glimmer of hope

With gold at £5 an ounce, all the state governments, except that of South Australia, provided assistance to experienced prospectors—usually £2 a week for married men and £1 for unmarried men. In South Australia, one lucky worker at a married men’s relief camp found a nugget worth about £60 while planting pines for the government.

In winter, those who were lucky enough to have a wood stove would burn anything they could find. People also put sheets of newspaper between their blankets and sheets to help them keep warm.

In 1931, 2,000 men were prospecting in Queensland alone. The gold hunters were encouraged by the tale of the ‘Golden Eagle’—a gold nugget worth almost £6,000—found by Jim Larcombe and his son near Kalgoorlie in 1931.

A few prospectors in Queensland found deposits of tin or silver, but gold was the main target because, even in a depression, there was always a market for gold.

Gold brought hope and, during the Great Depression, people welcomed even the faintest whiff of hope.

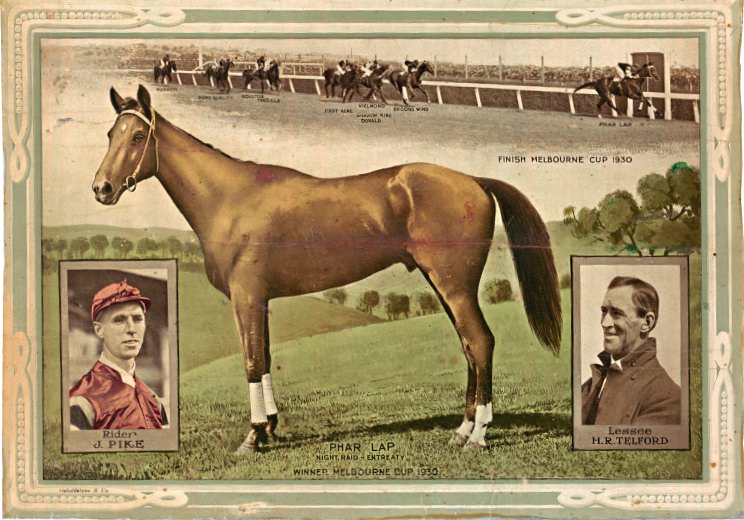

The mighty Phar Lap

Many Australians love their sporting heroes, and one of the greatest in the 1930s was Phar Lap, a chestnut gelding foaled in New Zealand. Phar Lap began racing in Australia in January 1929, and he was a symbol of hope in hard times.

The horse cost American businessman David Davis less than he expected, but he bought the horse based on its pedigree. However, when Davis saw the gangly horse with warts on its face, he refused to pay for its training. Harry Telford, the trainer, offered to lease and train the horse in exchange for two-thirds of any winnings. For a while, it looked as if Telford had the bad end of the deal, but he had faith in the ugly horse. That faith contributed to the legend that grew up around Phar Lap.

Phar Lap had his first win in April 1929. He was then spelled, before winning again in September. Racing journalists were now taking notice of the horse, and he was soon the favourite for the 1929 Melbourne Cup, which was run in November. He came third.

Phar Lap raced in the Melbourne Cup again in 1930 and won—his 14th win in a row! In the 1931 Melbourne Cup he came eighth, but he was carrying the very heavy weight of 68 kilograms.

Phar Lap after winning the 1930 Melbourne Cup.

Telford’s lease on the horse ran out, so he used some of his winnings to buy a share in Phar Lap, and thus became the horse’s joint owner. Davis insisted on taking Phar Lap to America by ship and, on 20 March 1932, Phar Lap won North America’s richest race, the Agua Caliente Handicap.

Then, on 5 April 1932, the magnificent horse collapsed and died in California.

In 1930, just before the running of the Melbourne Cup, a car with paper covering its numberplates had narrowly missed hitting the horse as it walked along a road. A few days later, two men in a car tried to shoot Phar Lap. They missed and drove away at high speed. People remembered these attempts to kill the horse and so, when Phar Lap died in the USA, people thought the worst. The rumour quickly spread that ‘our horse’ had been ‘poisoned by the Yanks’.

Many Australians already believed that the Americans had poisoned champion Australian boxer Les Darcy in 1917. Darcy did indeed die in the USA and, in a sense, he was poisoned, but it was by bacteria. He was suffering from bacteraemia, or blood poisoning, which was caused by an unknown bacterial infection. However, he probably actually died from pneumonia.

Phar Lap’s death may have been accidental. People who claimed to be ‘in the know’ said later that the horse was regularly dosed with a ‘medicinal’ tonic which contained either strychnine or arsenic.

Parts of Phar Lap are now held in museums. His heart is in Canberra, his skeleton is in New Zealand and his stuffed hide is in Melbourne. Forensic examination of the hide recently showed that Phar Lap was given a large dose of arsenic 30 to 40 hours before he died.

We do not know if that was what killed him, and we probably never will. But that did not matter to Australians during the Great Depression. As far as they were concerned, Phar Lap—their hero, their hope— had been ‘poisoned by the Yanks’.

Phar Lap raced in the Melbourne Cup again in 1930 and won—his 14th win in a row!

Toxic tonics

It seems strange to use poisons like strychnine and arsenic in medicinal tonics, but in the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century they were thought to be good for the blood and the heart. As well as being used as a tonic for racehorses, sportsmen such as marathon runners used tonics with strychnine in them. The trick was to use very small doses—but, if they got the dose wrong, they died.

Although the first Melbourne Cup race was in 1861, the actual trophy (the ‘cup’) was not awarded until four years later.

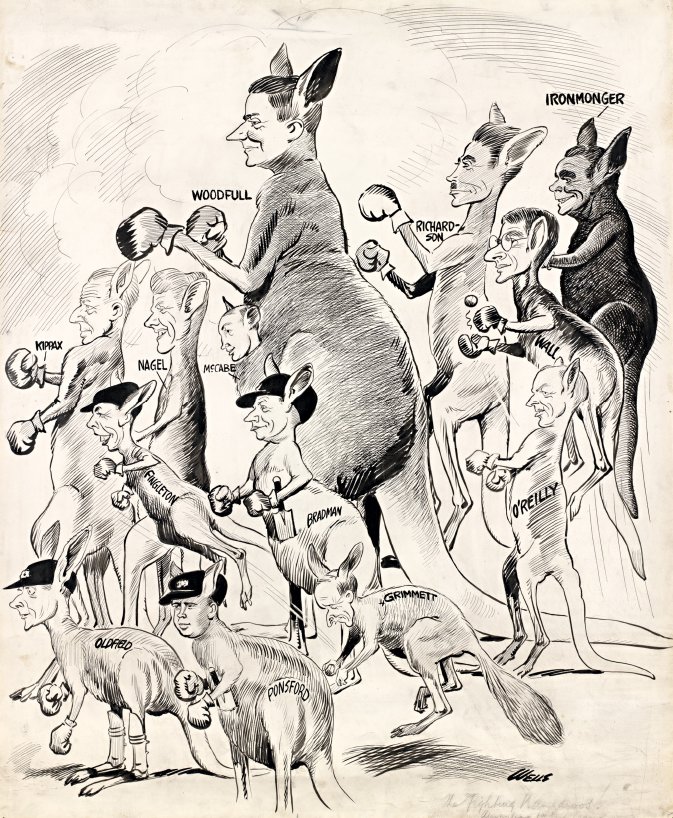

People often describe unsporting behaviour as being ‘not cricket’, but high-level cricket has always been about winning. The England–Australia test matches, known as ‘the Ashes’ series, were played in the 1930s in the summer in England, then two summers after that in Australia, then 18 months after that in England again. so there were two series every four years.

In mid-1930, a young cricketer called Donald Bradman played a major part in defeating the English team based at the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) in England. As they prepared for the 1932–33 season in Australia, members of the English team were worried because they thought England would not be able to win until Bradman retired.

The Australian crowd, who were well known for their barracking, did not like the new MCC captain, Douglas Jardine—and he probably did not like them. The Australians thought he was ‘posh’. Once, as he came in to bat, a barracker shouted, ‘Where’s the butler to carry the bat for you?’ Not surprisingly, Jardine thought the rude colonials did not show him the respect he deserved, so he was very keen to captain a winning MCC team.

Beating Bradman

After watching film of Bradman batting in the previous Ashes series, Jardine thought he had found a way to beat him. The aim was to use ‘leg theory’. When a batsman faces up to bat, the way he stands defines the ‘leg’ and ‘off’ sides of the pitch—the leg side is where his legs are and the other side is the off side.

Leg theory requires the bowler to aim at the leg stump. This makes it hard for a batsman to hit scoring strokes to the off side of the field, so more fielders are placed on the leg side. This slows down the run rate, and so most batsmen will take risks. It is legal, but it sometimes produces boring cricket.

Jardine observed that Bradman appeared uncomfortable with fast-rising balls down the leg side. He summed this up by saying, ‘He’s yellow!’—a coward. So Jardine had his bowlers aim the ball, hard and fast, at the body or the head of the batsman rather than at the wicket. The Australian press called this approach ‘bodyline bowling’ According to them, it was intimidation, not leg theory.

‘The Fighting Kangaroos’—caricatures of Australia’s 1932 test cricket team, a symbol of hope for Australia.

After watching film of Bradman batting in the previous Ashes series, Jardine thought he had found a way to beat him.

Batsmen did not wear helmets then, and the skull of Australian cricketer Bert Oldfield was fractured during one game. To be fair, the ball had come off his bat. However, bodyline bowling had been used to unsettle the batsmen and make them use their bats to protect themselves, so it was probably bodyline tactics that caused Oldfield’s injury.

One of our greatest batsmen, Don Bradman, in 1934.

After the bodyline series, Don Bradman went on to become one of Australia’s greatest cricketers. He collected an impressive list of achievements, including:

• averaging a test batting

score of 99.94 runs

• scoring 500 or more runs

in seven test series

• scoring 309 runs in a

single day’s play.

Many Australians had listened to the game on the wireless and they were outraged. One delegate to the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket wanted to appeal to the MCC to act ‘in the best interests of the game’. Other delegates argued that the captain and team managers should deal with it. In the end, no action was taken.

After the next West Indies tour, when the English players had bodyline bowling used against them, the laws of cricket were changed by the MCC to make sure that nobody ever again used the tactics that Jardine and his team had used in Australia. Many Australian sporting fans saw this as evidence that the English could dish it out but could not take it.

Some members of the Australian public were now a little less impressed with everything British.

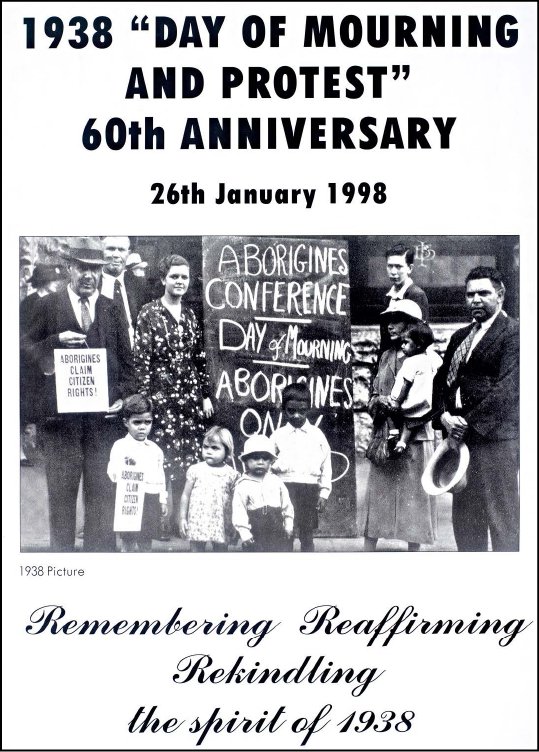

Aboriginal Day of Mourning

Because the Rum Rebellion happened on 26 January 1808, people talked about that day long afterwards. So we know that the colony’s birthday was celebrated with a holiday, but nobody knows when that habit had begun. By 1818, the 30th anniversary of settlement, 26 January was a public holiday. For a long time it was known as ‘Foundation Day’ or ‘First Landing Day’.

Celebrating ‘Australia Day’

By 1826, the 38th birthday of the colony of New South Wales, a toast was made to ‘Australia’ at the anniversary dinner, but it was a long time before it was officially called Australia Day.

In 1837, for the 49th birthday, a small regatta was held, with races for yachts, whaleboats, rowing boats called ‘gigs’, and ‘watermen’s sculls’—small racing boats. There were money prizes for first and second placegetters.

That set the scene for future Australia Days as a day of celebration and fun, although complaints in the newspapers about drunkenness were a feature of the day as far back as 1808. There was a bigger celebration in 1888, when the settlement reached its centenary, and it was even bigger for the sesquicentenary in 1938—the 150th anniversary of the first landings of white settlers.

Aboriginal concerns

People had been questioning the celebrations for some time. An official, Rudston Read, noted a conversation that he overheard in 1853:

I heard a native in the town of Sofala … chaffing a sergeant of mounted police … asking him what business had he or any other white fellow to come and take his land, and rob him of his gold? What would he … say, if black fellow went to England and ‘turn em Queen out’?

Read said this caused plenty of laughter from the gold diggers who were listening. Obviously, none of them took it seriously but, by 1938, some Aboriginal people had decided it was time to get serious.

Rather than joining in the sesquicentenary celebrations, they said that on 26 January 1938 they wanted a national Day of Mourning. Jack Patten, President of the Aborigines Progressive Association, put it well:

[W]e mourn over the frightful conditions under which the aboriginal has existed and is existing to-day in the continent which once belonged to our forefathers. We want ordinary citizen rights— old-age pensions, the maternity bonus, relief work when unemployed, and full rights to education for our children. We do not want to be herded in Government reserves and treated as a special class … we do not forget the bad deal we have had from the white man.

There are few accounts of the 1938 Day of Mourning and Protest, but it was remembered in 1998.

On 1 January 1938, anthropologist Professor Peter Elkin praised the Day of Mourning, saying that a great deal needed to be done. ‘All who are familiar with the history of the contact of black and white in Australia must sympathise with both the protest and the appeal,’ he said.

In 1967, Australians voted overwhelmingly in a constitutional referendum to give the Commonwealth the power to make laws to help Aboriginal people and prevent discrimination.

Members of churches and teachers of Aboriginal people related how the ‘natives’ often had trouble accessing their own money, did not have the vote and were sometimes refused permission to marry.

Aboriginal author and journalist David Unaipon, whose image adorns Australia’s $50 note, wrote that he thought the Day of Mourning was a bad idea because things were improving. It is likely that his disapproval may have been intended to make people think about the issue, and the Day of Mourning debate certainly raised awareness about the treatment of Aboriginal people in Australia. However, while Unaipon mentioned the improvements in conditions that he saw coming for Aboriginal people, there were actually very few improvements over the next 30 years.

Aboriginal groups gained the right to vote at different times, but all Aboriginal people had gained this right, in both state and federal elections, by 1965. In 1967, Australians voted overwhelmingly in a constitutional referendum to give the Commonwealth the power to make laws to help Aboriginal people and prevent discrimination. Australians also voted to finally count Aboriginal people in the official census.

From about 1936 onwards, a number of people realised that Germany was rebuilding its armed forces and so they began speaking about ‘the coming war’. Some preferred a policy of ‘appeasement’. They said that Germany had been harshly treated after the Great War and that anything was better than another war like the Great War.

Others thought there was no threat at all, including former President of the United States of America Herbert Hoover. ‘Statesmen are more generally alive to the dangers than they were in 1914,’ he explained. As he was a former US President, some people took notice of his words.

By January 1939, the New South Wales Government introduced planning and training for ‘air raid precautions’. In Adelaide, the Defence Society offered lectures on the care and use of gasmasks. In February, The Courier-Mail in Brisbane ran an article on gas-proof kennels because, it said, gasmasks did not fit dogs. Australia and the world were getting ready for the war that they knew was coming.

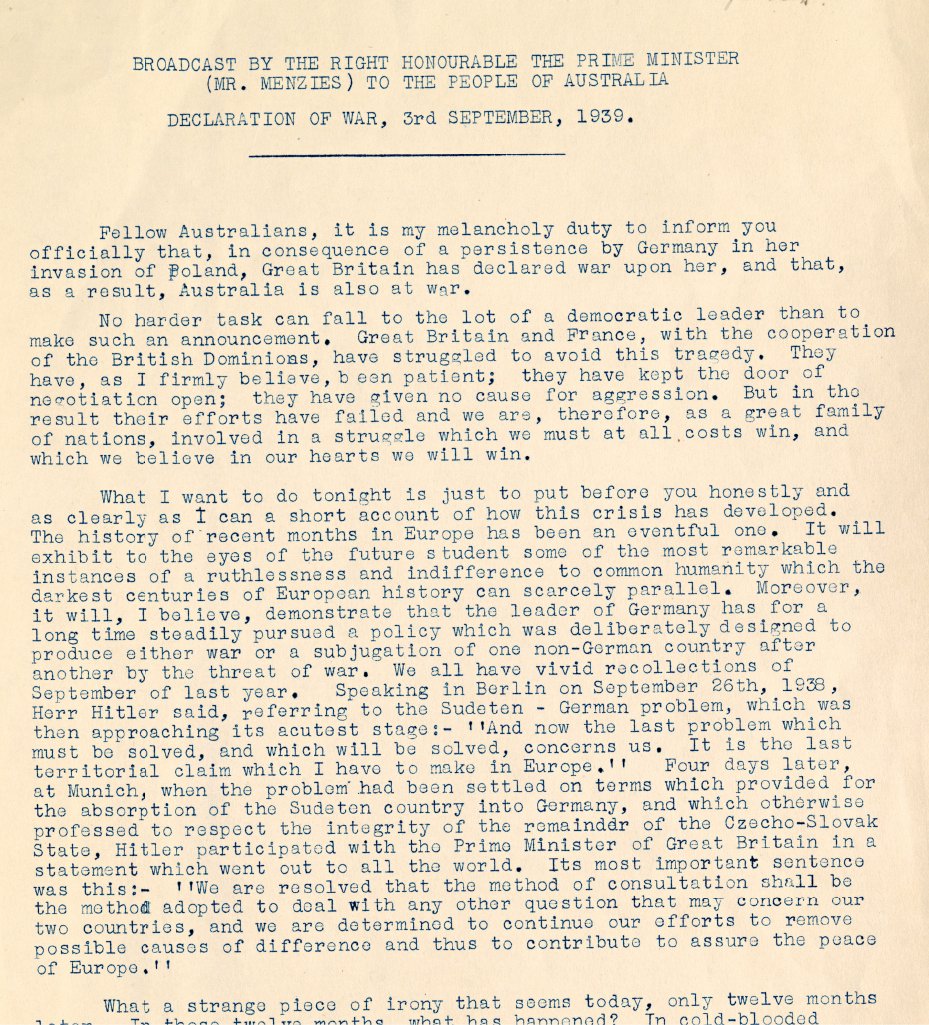

A ‘melancholy duty’

Because Australia followed Britain’s lead, with no questions asked by either our leaders or the Australian people, World War II began for us in the same way as the Great War had. Prime Minister Robert Menzies addressed the nation on 3 September 1939:

Fellow Australians, it is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that, in consequence of the persistence of Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.

Prime Minister Robert Menzies in a broadcast to the Australian people, announcing that the nation was at war.

The first page of the broadcast—it was three pages long.

Earlier in 1939, Menzies still did not think there was any threat to Australia. While other Australians were worried about Japan, Menzies had approved the sale of scrap iron to Japan in 1938. His opponents nicknamed him ‘Pig Iron Bob’.

Five days after the war started, the British Government asked for Australian troops to help defend Britain. As a very ‘British’ Australian, Menzies drew up plans to send Australian forces, including aircrew, to Singapore and North Africa to support Britain.

A very different war

World War II was a very different war to the Great War. Air power changed everything. People understood this when they read how German pilots used dive-bombers to destroy cities and blast troops. There would be no trench warfare this time: bombers in the air as well as tanks on the ground meant there would be no getting bogged down in trench warfare as the armies had been in the Great War.

The new war was also a very different war because almost no horses were used. A few horses and mules carried supplies up the Kokoda Track in Papua New Guinea, where vehicles could not go, but that was unusual.

Because Australia followed Britain’s lead, with no questions asked by either our leaders or the Australian people, World War II began for us in the same way as the Great War had.

It was a very different war because women played a larger part. In the Great War, women had worked as nurses, but in World War II they also did clerical work and drove trucks, as well as many other tasks.

And it was a very different war because the Australian mainland came under direct attack.