Italian migrant market gardeners near Adelaide in 1960.

During the Great War, the only thought was to win but, in World War II, the government talked about what a postwar Australia should be like. It developed plans in many areas, such as education, employment, social welfare, health, conservation, industry organisation, town planning and regional development, and immigration—all to build a better Australia. In the years after the war, some of our dreams became real— we finally starting manufacturing an Australian car; we welcomed migrants from many lands, making Australia’s culture richer; we started constructing the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme; television arrived; and almost everyone who wanted a job had a job.

Italian migrant market gardeners near Adelaide in 1960.

Teaching materials used in 1949 to teach English to the people we now welcomed as ‘New Australians’.

By the end of World War II, much of Europe was in chaos. Hundreds of buildings, towns, cities, railways and roads had been destroyed, and refugees were everywhere.

Displaced persons

In late March 1945, five weeks before the war ended on 8 May, the Adelaide Advertiser reported that Europe had eight million ‘problems’—displaced persons. During the war, many of them had gone voluntarily to Germany seeking better pay, but others had been forced to go there. After the war, those from Belgium, the Netherlands and France were sent home so their police forces could work out who had collaborated with the Germans and punish them. However, the Russians and the Poles had all been forced to work in Germany.

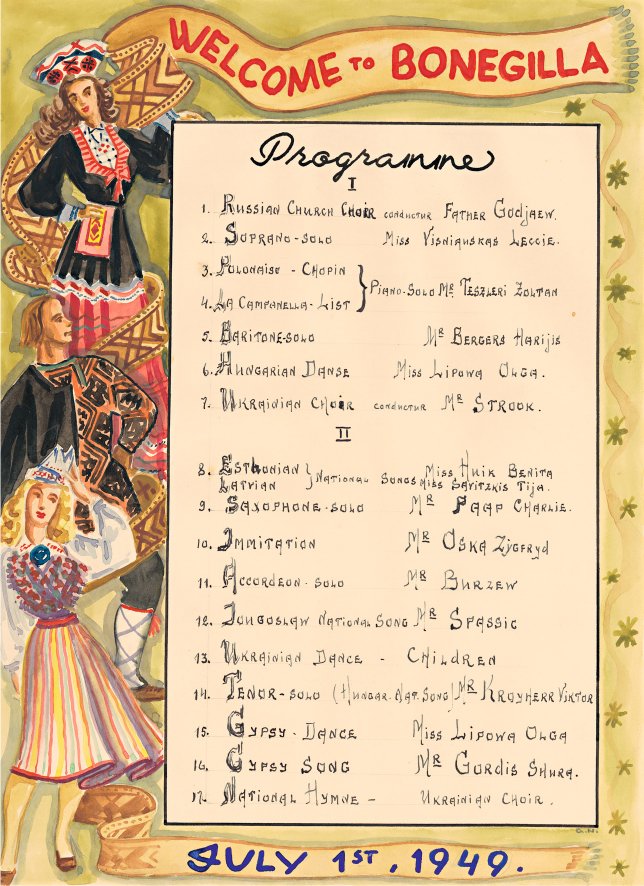

A program for a concert at Bonegilla, Victoria, a hostel for newly arrived migrants, 1949.

In late March 1945, five weeks before the war ended on 8 May, the Adelaide Advertiser reported that Europe had eight million ‘problems’—displaced persons.

Once Germany collapsed, Russian displaced persons could be sent home, but many of them did not want to live under Russian dictator Joseph Stalin. So, once the war ended, they sought safety in Western countries, such as Australia. Sadly, some of the Allies behaved treacherously, sending war heroes back to Russia, where many innocent people ended up in Russian prison camps.

Many of the survivors of the Polish air force had fought gallantly in other countries against Germany throughout the war. They did not want to return to Poland, which was now controlled by the Russians. The British Government did not want the Poles to stay in Britain, so they tried to persuade Australia to take some of them.

This couple arrived in Australia in 1948 on the Norwegian ship, the Svalbard.

Travel to Australia by steamship was cheaper than by aircraft. Today, a return flight to Europe costs about two weeks pay for an average worker, but in 1946 it cost more than two years pay! No wonder most migrants opted for the much longer and more uncomfortable sea voyage. But, even with the cheaper option, to help pay for their fare, migrants agreed to work for two years wherever they were sent to in Australia.

Migrants used to come to Australia on large ships.

A new word had come into popular usage in Australia during the war—‘reffo’. Short for ‘refugee’, it was not an offensive term when Australian poet Leon Gellert used it in a newspaper article in April 1945. However, by January 1947, politician Jack Lang clearly meant to be offensive when he referred to Arthur Calwell, the Minister for Immigration, as the ‘Minister for Reffos’.

On the surface, the governments in Canberra and London both emphasised the need to bring people to Australia from Britain but, while politicians said one thing, the planners said another. Australian politicians, from Joseph Cook onwards, used the catchcry ‘populate or perish’, but planners knew that Australia needed skilled people, not just people who could dig, cut and carry. Australia was moving into a world where machines did much of the hard work, and so the country needed people who could design and make machines, as well as people who could use, mend and repair them.

Engineers, scientists, machinists and other people with technical training were taken in, as Australia welcomed skilled workers from around the world—so long as they had ‘white skin’. The government thought that, coming from warmer places, southern Europeans would be able to work in the hotter parts of Australia, so Yugoslavs, Greeks and Italians were also welcomed.

Settling in Australia

Travel to Australia was as unpleasant for many of the migrants in the late 1940s as it had been in the 1800s, but at least steamships got to Australia faster than sailing ships. They found that the ships were still crowded and noisy, and food that suited migrants from one nation often did not suit those from another. So migrants suffered on the trip out to Australia and, when they arrived, they often suffered even more in the ‘migrant hostels’ where they were housed.

The biggest hostel was at Bonegilla, near Wodonga in Victoria. More than half the postwar migrants— around 300,000 of them—spent some time there. They learned to speak English, and they also gained a new name—‘New Australians’. On the other hand, migrants from Britain were labelled ‘Ten Pound Poms’ because they paid £10 each to migrate to Australia.

Once the migrants left the hostels, an ABC radio program called English for New Australians broadcast lessons for them. Bernhard Hammerman, a prewar refugee, played the part of ‘Paul’, a foreigner whose mistakes were corrected by the other radio actors. Hammerman lost the role when his pronunciation became insufficiently ‘foreign’!

The new arrivals did not have a lot of choice as to which jobs they worked in, and their qualifications were often ignored. Those who refused jobs were pressured until they accepted whatever was offered.

After two years, the migrants and their children were free to make their own lives, and many of them did very well. Migrants have made Australia a more diverse, richer and more interesting place.

Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme

‘Endless’ resources

Most of the first white settlers in Sydney regarded the land as a resource to be used. If it could not deliver a profit in some way then they thought it was being wasted. They cut down trees to build huts and quarried stone to make larger buildings. Clay was dug to make bricks, and the brick ovens were fired with local firewood.

On a new farm, trees were cut down for timber or firewood, or for bark to make huts, or to clear the ground so grass could grow. Rivers running down to the sea were dammed to supply water in times of drought, or used to turn millwheels, or channelled across paddocks to make crops grow. Rivers could also be stocked with fish to provide food.

The Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme opened up the high country for all Australians to enjoy.

People believed that the sand could be removed from beaches and dunes because more sand would wash in. They thought clay and mud from gold dredging could be dumped in rivers because the constant flow of water would carry it away, sooner or later.

In The West Australian newspaper in 1905, a scientist visiting Australia spoke of the ‘somewhat new science known as ecology’. However, it took the public a while to understand how species and the environment interact with each other, how cycles of floods and droughts affect the Murray Valley, or how dead trees in a forest are important parts of the natural ecosystem. They did not understand that, in nature, nothing is wasted.

Harnessing the mighty rivers

Australians had barely recovered from the shock of the Great War when the Great Depression arrived. Then came World War II, and even after the war they still had to put up with rationing and hard times. In the late 1940s, Australians needed some good news, and the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme looked like a positive plan towards recovery.

Each spring, melting snow in the high country of the Australian Alps, the Snowy Mountains, fed into the Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers, then finally flowed ‘unused’ into the Southern Ocean. When people recognised this in the early 1900s, blocks of irrigated land were opened up near the Murrumbidgee River. There was just one problem: in some years, there was not enough water during summer.

Each spring, melting snow in the high country of the Australian Alps, the Snowy Mountains, fed into the Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers, then finally flowed ‘unused’ into the Southern Ocean.

Even in a drought, some water trickled out of the mountains, all summer. It flowed north and then west in the Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers, or down the Snowy River, south to Victoria’s Gippsland region and into Bass Strait. The water came from a giant mountain-top ‘sponge’ of sphagnum moss. People thought dams in the high mountains could hold the spring floods, and release the water when farmers needed it. Then engineers asked about all the ‘wasted’ water in the Snowy River. They dammed the Snowy and sent its water north through tunnels to the Murray-side of the alps where it could be used for growing crops and generating clean, free hydro-electricity.

Once a project has begun, a new government cannot usually stop it completely. On 17 October 1949, just eight weeks before the December federal election, the Labor government began work on the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. They probably wanted to lock the project in place, as well as wanting to be seen to be doing something positive.

When a new government was elected, the work continued. And it kept going throughout the 23 years of Liberal Party rule, finishing on time and on budget in 1974 under the Labor Party government of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.

More than 100,000 people from 30 countries, living in over 100 camps and seven new towns, completed 1,600 kilometres of roads and tracks, 145 kilometres of tunnels, 16 dams and seven hydro-electricity stations. Over 25 years, 121 workers died building the project.

Then, as the last workers moved on, the area was opened up for a new Australian winter pastime— snow sports, mainly skiing and later snowboarding. In summer, many tourists also arrived, keen to walk or mountain bike in the high country. Others rode the chairlifts to the ridges, before following level walking tracks.

The Snowy River Hydro-Electric Scheme proved that Australia was a ‘can-do’ nation. However, there were environmental costs. Many animal breeding cycles are triggered by floods but, with dams, floods are rare, and today there are still discussions about the importance of environmental flows (the amount of water rivers need to stay healthy).

Even the carbon cost of such a project is now thought to be higher than people expected. On average, it takes about 400 years for a hydro-electric scheme to cover all of the carbon costs associated with its development.

Despite this, the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme was a significant achievement.

Australia’s own car

Originally, motor vehicles were entirely made and assembled in Australia, like the Thomson steam car. Then vehicles were imported whole, but later the main parts—engines, chassis and wheels—came by ship and the bodywork was made in Australia. The car bodies were done by people already familiar with making vehicles— carriage-makers.

The Holden company

James Alexander Holden sold harnesses and saddles in Adelaide in 1856. In 1885, he joined forces with Henry Frost, a carriage-builder. In 1905, James’ grandson Edward joined the firm of Holden and Frost and, by 1908, the company was involved in repairing the upholstery in motor cars.

Car bodies being made at the Holden and Frost Motor Body Works, Adelaide, about 1925.

Among the names which were considered for Australia’s first car were ‘Melba’, ‘Emu’, ‘GeM’, ‘Austral’, ‘Woomerah’, ‘Canbra’ and ‘Boomerang’! The name finally chosen was ‘Holden’, after the founder of the company that developed it.

During the Great War, German submarines tried to sink as many cargo ships as possible. So, to reduce the number of ships sailing, overseas car-makers started sending just chassis and engines, instead of whole cars, to Australia. The local importers needed people who could make car bodies on a large scale. Holden and Frost took up the challenge, and kept going after 1918.

The company changed its name to Holden’s Motor Body Builders (HMBB), and it was making 12,000 car bodies a year in 1923. In 1924, HMBB began making car bodies for General Motors—an American company which bought HMBB in 1931, thus creating General Motors Holden (GMH).

During World War II, the company’s factories switched to war work. Then, towards the end of the war, the government started looking around for somebody to make an all-Australian car.

In November 1944, both Ford and GMH were interested in the idea. By March 1945, discussions were getting serious and the government had received proposals from both companies. It also expected to get at least one proposal from a British manufacturer.

The GMH plan assumed a delay of about two years after the war finished. As that was promised in March 1945 and the war looked like ending soon, it was accepted. In May 1945, just days before the Germans surrendered, GMH said that the delay would now be a mere six months.

On 8 May, the day the Germans surrendered, laws were passed to make an Australian car possible. An opposition speaker in the Federal Parliament said that he hoped the result would be tractors costing just £200 and cars and utilities costing £300. Soon after, GMH went back to predicting a likely delay of two years.

By late July 1945, overseas companies Chrysler-Dodge and Nuffield were interested in making an Australian car as well but, a year later, only GMH was still in the race, and the company was ‘tooling up’. In April 1947, newspapers reported that the cars were being secretly road-tested. By February 1948, the promise was for ‘late this year’ and, on 2 September, a completed model was finally shown to the press. It was to be named the Holden and would probably cost £600 (nearly twice the annual basic wage for men and three times for women).

It had been 92 years since James Holden had started his business, 43 years since the company started working on cars, and three-and-a-half years since the idea was first floated for an Australian car, but Australia now finally had its very own car.

By the 1950s, people began to fly to their holiday destination and then rent a car.

Striking workers

By 1949, Australia was ready for political change. The British Government had demanded that Australia keep rationing petrol to help Britain’s economy. At the same time, Australian unions were getting ‘Bolshie’—a British term, based on the word ‘Bolshevik’, the old Russian name for communists. There were communists in many of Australia’s unions, but they were in a minority. Saying ‘the unions are getting Bolshie’ was a way of attacking the unions.

Coalminers went on strike in the winter of 1949, at a time when people relied on coal fires, gas made from coal, and electricity generated by steam, in turn made by burning coal. On the docks, waterside workers went on strike without warning, holding up the mail and the delivery of goods.

In fairness to the strikers, coalmining was a difficult and dangerous job, and many miners died of ‘black lung’ from coal dust, or in explosions or cave-ins. It was hard, physical work. Working on the wharves was just as dangerous. Most goods were in bales or boxes that had to be hauled by hand or using small cranes.

The workers wanted more money to compensate for their dangerous jobs. Because their work was vital, their strikes were effective. Not surprisingly, people were fed up with the shortages caused by strikes and rationing. They were ready for a change, and they thought a new government would make a difference.

Robert Gordon Menzies (later Sir Robert), Australia’s longest-serving prime minister. He stayed in power because he was a very skilful politician who knew how to deliver a simple message.

Menzies takes control

Led by Menzies, the Liberal Party swept into power in 1949 and immediately abolished petrol rationing.

The United Australia Party (UAP) had collapsed in 1941 after Menzies was deposed as leader, but he was re-elected as leader after Labor’s landslide win in 1943. He reconstructed the UAP as the Liberal Party of Australia in 1945, but lost the 1946 election and considered leaving politics altogether.

Then Ben Chifley, who had become prime minister when John Curtin died in July 1945, decided in 1947 that the government should take control of the banks. Menzies, who was against this, had found a cause to fight for, and so he stayed in politics.

Menzies had been in Europe, where the Cold War between Russia and Western Europe had started and another real war seemed likely to break out. He argued that the Labor Party’s union allies were sympathetic to the communist Russians and that the government taking over the banks was a socialist act— and communists liked socialism!

His logic was poor, and the members of the left-wing parties said he was ‘kicking the Commo can’, but the tactic worked. Once he was prime minister, Menzies introduced a bill to outlaw the Communist Party of Australia. Labor still had a majority in the Senate and so they amended Menzies’ bill but, with the Korean War under way, Menzies put the bill forward again.

If Labor had rejected the bill twice, Menzies would have gone to an election and probably won again, so the Senate passed the bill and it became law. Then, in March 1951, the High Court declared the law unconstitutional and, in September, the Australian people narrowly defeated a referendum to amend the Australian Constitution to make banning the Communist Party lawful. So, the Communist Party still legally existed.

Once he was prime minister, Menzies introduced a bill to outlaw the Communist Party of Australia.

Australians survived with the Communist Party in their midst, although there were ongoing effects such as the ‘Petrov Affair’, when two Soviet diplomats defected to Australia. Later, the Democratic Labor Party was formed by those who split from the Australian Labor Party, because right-wing union organisations in the Labor Party thought that there was undue left-wing influence from communist union leaders.

A consummate politician

Menzies probably believed all the scare stories about international communism, but he was also a very astute planner. At that time, politicians who were good orators and could deliver a convincing speech were admired.

People said that Menzies responded to interjectors with quick, witty answers. His replies were certainly clever, but they were not necessarily quick. When he was interrupted, he would stop, begin the sentence again, finish it, and then respond to the interjector.

To deter competition, Menzies found ways to remove rivals for the prime-ministership. He offered them high offices so that they would no longer be competitors. For example, Sir Garfield Barwick became a chief justice and Richard (Lord) Casey became governor-general.

Menzies was lucky to lead Australia in a time of growth and prosperity. One of his greatest achievements was creating the Murray Committee. Its 1957 report recommended opening new universities and granting more scholarships so that many young Australians could be the first in their families to get a university education. Menzies had always cared passionately about Australian education. Even when his party’s fortunes were at their lowest, in 1944, he argued that Australia needed more universities.

Expansion of the suburbs

In the early days of settlement, the size of a city or town was limited by the need to get supplies of food and water in and waste out. On top of that, everybody needed to live near where they worked, so people packed in close together. Unfortunately, this meant it was easier for diseases to spread. When modern forms of transport were developed, people could live further away in what are called suburbs.

Living on a quarter-acre block

The picket fence on a quarter-acre block (photo taken between 1964 and 1970).

At the end of World War II, the suburban dream involved a nuclear family—two parents and several children—living in a home on a quarter-acre (about 1,000 square metres) block, often with a car in the garage and a white picket fence. This ‘paradise’ offered room to breathe, with perhaps a small vegetable garden and a few fruit trees. People wanted to live ‘the good life’.

Most suburban blocks were smaller than a quarter of an acre, but they were still large enough to cause ‘urban sprawl’ as the suburbs spread out from city centres. That brought all sorts of problems. As new land was opened up, councils and government authorities struggled to provide services—roads, parks, libraries, schools, power, gas, water, drainage, sewerage and public transport.

The milkman delivering milk to suburban homes (photo taken between 1964 and 1970).

Public transport was a major problem. The very first arrivals found no public transport, so they bought cars. This meant that there was no demand for public transport. Later, as more people moved into the suburbs, they had to buy cars as well. Later still, when people asked for public transport, they were told that everybody had cars, so there was no need for buses and trains.

The dream of living in a home on its own block remained popular, but often each new suburb would be filled with families of much the same age. Schools had to be built to accommodate the children of these, often young, families. Then the demand for schools shrank as the children grew up but stayed in the area with their parents. When the parents retired and moved out of the area, new families moved in and the number of school-age children went up again.

Older suburbs usually had a better mix of age groups because, over time, the cycles evened out. However, in the newest areas—the furthest-out suburbs—the age balance was still often missing.

The standard of medical treatment improved during the twentieth century. Hygiene was better and children were inoculated against a number of killer diseases, so young children were much less likely to die. Parents began to have fewer children, and that left them with more money to spend on making a better life for both themselves and their children.

More children stayed at school for longer, more went to university, and more learned skills. Most of the hard physical work had once been done by unskilled labourers, but now there were machines to dig ditches and holes or move heavy loads around. Australia needed trained workers who could make, look after, use and repair those machines. Skilled people earned more money, and so people grew richer and moved out into the suburbs.

The milkman called each morning to deliver milk in glass bottles, a butcher’s boy collected orders and delivered the meat, the grocer did the same, and even fruit was sold from carts.

The corner shop

With families getting smaller and building blocks getting larger, the population density—the number of people to each hectare—fell. The old retail model in a suburb involved a number of corner shops, plus the occasional cluster of shops with a greengrocer, a butcher, a grocer, a chemist and a few other specialty shops like hardware, clothing and shoes.

Corner shops like this one used to be common (photo taken between 1964 and 1970).

In the 1940s, small children were often sent to the corner shop to buy groceries, and they could usually get there without crossing a road. If they had to cross a road, there were not many cars and so children would usually hear them well before the cars got too close.

The milkman called each morning to deliver milk in glass bottles, a butcher’s boy collected orders and delivered the meat, the grocer did the same, and even fruit was sold from carts. A baker’s cart came each weekday with bread, and the iceman delivered large blocks of ice for the ice chests that would soon be replaced by gas and electric refrigerators.

Another corner shop (photo taken between 1964 and 1970).

Selling the dream of eventually owning your own home—an advertisement for a new suburb in Newcastle.

These systems did not work very well in thinly populated new suburbs, which had few homes per hectare and few people per home. There were not enough people within walking distance of a corner shop and the delivery people had to travel too far. The corner shops survived for longer in the old, heavily populated inner suburbs, but the small groups of shops either became shopping centres or were bulldozed and replaced with home units, from which people drove to large shopping centres.

About the 1970s, town planners and architects started arguing for more compact living to reduce the urban sprawl. Once again, the suburbs and people’s lifestyles changed.

Television comes to Australia

Early attempts

As early as 1885, inventor Henry Sutton had tested the ‘telephane’, a system for sending images of the Melbourne Cup race to Ballarat. Australia’s first experimental television transmission happened in Melbourne in 1929. It was called ‘radiovision’. There were serious television trials in 1934 using radio station VK4CM, broadcasting to 18 receivers in Brisbane. However, none of these trials led to further developments.

After World War II, many trained radio and radar technicians had the skills to work in television. With the Olympics being held in Melbourne in 1956, the time seemed right to introduce television.

Decisions had to be made about technical standards, but many of these standards had disadvantages. If Australia adopted American standards, more programming would come from America. If British standards were used, then British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) material would be favoured. There were no commercial television stations in Britain in the 1950s.

Not surprisingly, British standards were adopted for transmission, but the Liberal government wanted to allow commercial television. By 1956, American programs could be delivered in a format that all the Australian channels could use. The government was worried that television might fail, and so it allocated commercial licences to established newspaper publishers.

Broadcasting to the nation

Early television sets had a small screen in a large box that contained the circuits and a giant cathode-ray tube. They were called ‘black-and-white’ TVs, but they were really dark grey and either greenish or bluish. The early electronics used thermionic valves—thumb-sized tubes that did the same work as a transistor but gave out more heat.

Men on TV appeared to be wearing white shirts, but actually they wore blue, because white looked grubby in the transmission. Fabrics were plain, with no stripes or fine checks because they caused ‘strobing’ when the scan lines of the camera interacted with the pattern in the fabric, and that was hard on the eye.

Where possible, scenes were taken in a single shot, and a lot of programs were broadcast live. Footage could be inserted into a program but, in the earliest days, there was no videotape, so the footage came from movie film fed through a machine that turned the film into a television signal.

Early television sets had a small screen in a large box that contained the circuits and a giant cathode-ray tube.

Many people around the world became aware of fictional versions of Australian life through television programs like the children’s drama Skippy the Bush Kangaroo, and popular ‘soapies’ like Home and Away and Neighbours.

When wireless began, stations hired stage performers, and a few of them succeeded in the new medium. With the arrival of television, radio performers and programs were often poached, although only radio quiz shows seemed to survive the shift to television.

The take-up of television was slow. At the end of the 1950s, less than 5 per cent of homes in Melbourne and 1 per cent in Sydney had a TV set. The 1956 Olympics were available on TV in Melbourne but, until a coaxial cable was laid in 1963, there was no transmission from state to state. By 1967, television stations could get satellite links to overseas and, in 1975, colour television reached Australia.

A rehearsal for a television program in the late 1960s.

From the 1980s on, multiculturalism was promoted on television with the establishment of the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS), which brought Australians a wide range of television programs from around the world.

Two victims of television were suburban cinemas and drive-in theatres, because many people now stayed at home to watch ‘the box’ rather than going out to see a movie.

Television continues to evolve, with analogue broadcasts now replaced by digital transmission.

Through television, well-known people became more recognisable, including politicians such as Prime Minister John Gorton, seen here watching television in 1968.

Related newspaper articles of the time

The state of television in 1928 (overseas).

In 1932, progress with television was slow.

An early test of television was being planned in 1949.

Explore more