A huge crowd crossing the Sydney Harbour Bridge during a Walk for Reconciliation, 2000.

Many factors drove the social changes of the 1960s—fear of atomic bombs, desire for better education, awareness of the importance of the natural environment and, most importantly, the sudden understanding that, if enough people stood together and demanded the same thing, governments could be forced to change their minds. People could hear about issues on the radio or read about them in a newspaper, but the impact of actually seeing events on television was huge. Australia changed.

A huge crowd crossing the Sydney Harbour Bridge during a Walk for Reconciliation, 2000.

Singer Paul Kelly, writer of protest songs.

Seeking independence

In the 1850s, Napoléon III of France was the ruler of a small empire. His uncle, Napoléon Bonaparte, had sold a large slice of North America, called ‘The Louisiana Purchase’, to the USA in 1803. After Bonaparte was defeated in 1815, the other European powers acted to try to stop France from ever again becoming a major power.

In 1854, many Australian colonists were upset that the French had seized New Caledonia and sent convicts there. But, in 1859, most Australians were not particularly interested when the French began taking over Cochin China, part of what was later called Indochina, which now includes Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam.

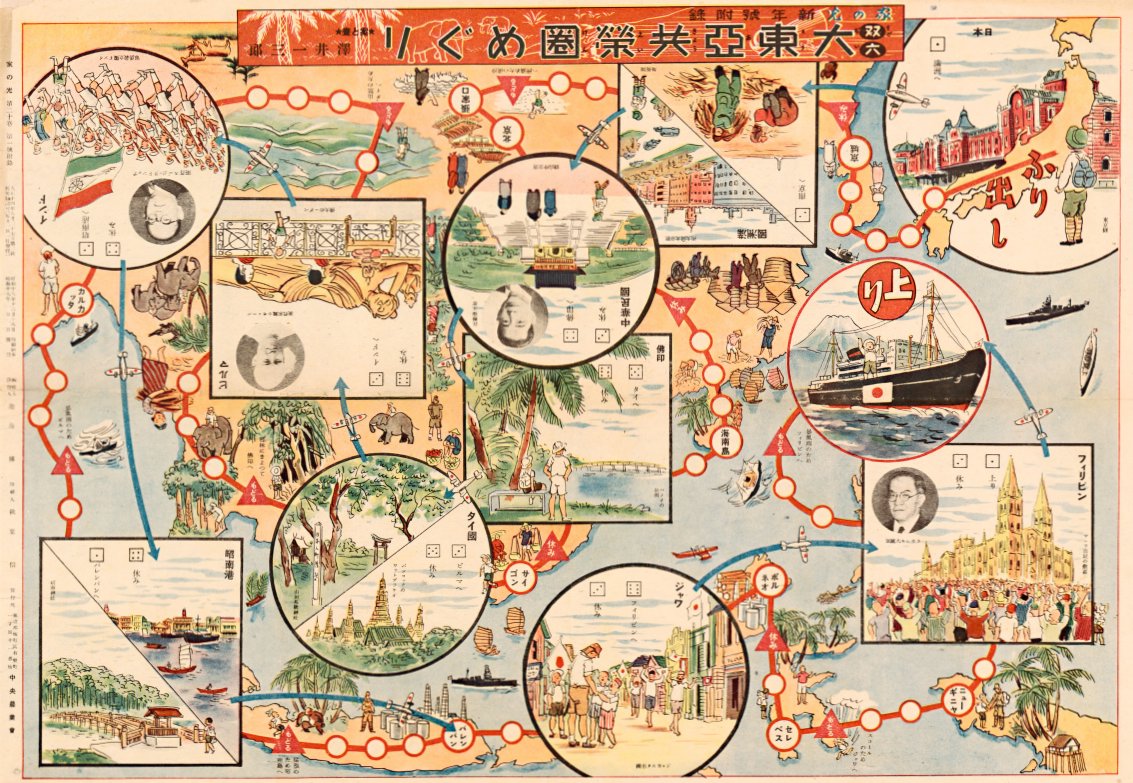

When the Japanese proclaimed the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and then invaded most of South-East Asia during World War II, they said it was time for Asians to stand together against the exploitation of the colonialists. In reality, the main aim of the Japanese was probably to have colonies of their own.

In 1945, as the Japanese began to lose the war, the Asian nations sought independence from them. In China, the nationalists and the communists had been allies against Japan but, after Japan was defeated, they began to fight each other. America supported the nationalists, while Russia, keen to promote international communism, supported the communists.

In this 1944 Japanese board game, players travel to other countries of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Communist theory says that revolution can come about only when the people rise up against their oppressors, and not through a war. In real life, such grand theories do not always work and so, through war, the communists took over China and international communism seemed to have won.

India and Pakistan became independent from Britain in 1947, but the Dutch wanted to keep Indonesia as their colony. The PKI—the Indonesian Communist Party— formed a peaceful coalition with other parties that were trying to win control, and then waited for the right time to act. Gaining independence from the Netherlands took four years, and it happened because of strong support from India, Australia and the USA. In late December 1949, the Dutch recognised Indonesian independence and withdrew their troops. The USA and Australia immediately recognised the new nation.

Vietnam

The situation with Vietnam was different. The Vichy French Government effectively gave Indochina to the Japanese in 1940. Throughout World War II, the USA supported the Viet Minh—a coalition of Vietnamese nationalists and communists.

In September 1945, British and French troops invaded Vietnam. This was the beginning of the First Indochina War, in which France was supported by the USA. The French were beaten at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, and Vietnam was divided into a communist north backed by China, and a non-communist south backed by the USA.

The first US military advisers appeared in South Vietnam in 1950, their numbers increasing after 1954. In 1965, the first US troops went to South Vietnam, and the USA then asked its allies to help. Britain and Canada, who were members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), refused; however, the United States’ allies in the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) agreed, with Australia, New Zealand, Korea, Thailand and the Philippines all sending troops.

These countries agreed to do this because they feared that recent history would be repeated. Japanese troops had invaded much of Asia in the 1940s, and now politicians painted a fearful image of international communism moving south in the same way. Each nation was seen as a potential domino which, in falling to communism, would knock the next nation down. It was a simple theory and, in hindsight, it was wrong, but it was accepted by many at that time.

In Sydney, the anti-war protests got larger and larger.

Moratorium marches

Unlike many of the earlier wars in which Australia was involved, there was strong opposition at home to Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. There were huge antiwar ‘Moratorium’ marches around the country. This was partly because it was the first war that people saw firsthand on their television screens. The opposition to the war was often hard for Australian troops fighting in Vietnam to accept—either then or now.

Conscripting Australian troops

Australia lacked the troops needed to provide a battalion in 1965 and a full task force in 1966, so the government introduced conscription. All 20-year-old men had to register, and then there was a ballot based on date of birth. If their birth dates were selected and the young men passed a medical test, they had to leave their jobs and join the army. They were given military training and some were sent to serve in Vietnam.

If their birth dates were selected and the young men passed a medical test, they had to leave their jobs and join the army.

There were various ways to avoid conscription, including claiming to be a pacifist, but objections on political grounds were not accepted, despite a growing groundswell of political opposition to Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Those who tried to ‘dodge the draft’ risked being sent to jail.

In the end, the communists won in Vietnam, but the tide of international communism had run out of momentum and no more ‘dominoes’ fell. By then, more than 3,000 Australian troops were wounded fighting in the Vietnam War, and 500 men died, including 200 conscripts.

Dismissing a government

The election of a Labor government at the end of 1972 came as a shock to the Liberal–Country Party coalition, which had been in government for 23 years.

Labor Party leader Gough Whitlam had led his party into power with one of the greatest Australian political slogans—‘It’s time!’—and promises of change. Twenty-three years is a long time in opposition and the members of the new Labor government had no previous experience as ministers. That inevitably caused problems. Once in opposition, the Liberal–Country Party coalition pursued a blistering campaign of negativity—as every opposition does.

Governments can be defeated if the opposition can force enough government members out or get them to change sides. Oppositions try to force an election when the government is unpopular. Governments stay in power by keeping their allies close and by holding an election when the government is popular.

Only the governor-general officially has the power to call an election. However, according to Australian parliamentary conventions and the Constitution, the governor-general can call an election only when advised to do so by the government.

Australia has two houses of parliament—the House of Representatives and the Senate. The Senate can defeat or change any bill, but it cannot introduce ‘money bills’—the bills that provide the government with money to spend on running the country. This leaves the Senate with a negative role, because it can still veto a money bill—called ‘refusing supply’. If supply is refused, the government has no money to keep going and it must call an election.

The election slogan ‘It’s time’.

The rules for electing senators are complicated, and usually neither side wins a majority. The final decision, the balance of power, often lies with a handful of independents and members of minority parties.

If the Senate continues to refuse to pass legislation, the Australian Constitution says that the prime minister can advise the governor-general to call a ‘double dissolution’. This means that all positions in both houses of parliament are declared vacant and all members and senators must face re-election.

If the Senate still refuses to pass legislation after a double dissolution, a joint sitting of both parliamentary houses is held, with a simple majority deciding the outcome. In 1974, the opposition’s refusal of supply was dealt with in this way. In politics, many rules are set out in the Constitution, but other rules exist as unwritten rules called conventions. These are usually based on courtesy and decency.

To gain a small advantage in the next election, due in 1977, the Labor government appointed lawyer and Labor Senator Lionel Murphy to a vacant place as a judge on the High Court. This annoyed the opposition, but it was within the rules.

Then the Premier of New South Wales, Liberal politician Tom Lewis, decided to ignore a longstanding convention. This convention was that a state government appoints a replacement senator who has been nominated by that senator’s party.

Instead, Lewis appointed the Mayor of Albury, Cleaver Bunton, who was not aligned to any party, to replace Senator Murphy. This outraged both the Labor Party and the executive of Lewis’ Liberal Party. Bunton understood the convention and, while he was a Liberal appointee, he supported the Labor government on all the 1975 money bills.

Australia’s new national anthem, Advance Australia Fair.

Advancing Australia

During the short time it was in government, Gough Whitlam’s Labor government made some significant changes. Among many other initiatives, it abolished the death penalty, introduced legal aid for those who could not otherwise afford a lawyer, made tertiary education free, and introduced a new national anthem, Advance Australia Fair.

The next break with convention came when a Queensland Labor senator died and, instead of appointing the person the Labor Party had nominated, Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen appointed Albert Field. Although Field was a member of the Labor Party, he was an opponent of the Whitlam government.

The Dismissal

Field had not yet taken his seat when the crisis that led to ‘the Dismissal’ emerged, so the Senate was still one member short. When a senator from one party is absent, it is the convention that the other party arranges for one of its senators to also be absent from the Senate. This makes sure that when the senators have to vote on legislation, the results are fair. Because the federal opposition knew it could probably win an election as the government was unpopular, it ignored the convention and did not withdraw one of its senators. As a result, the opposition now had a majority in the Senate and refused supply, which meant that the government could not do anything and would have to call an election.

While negotiations were going on to persuade the opposition to grant supply, Governor-General Sir John Kerr joined in secret discussions with the opposition and conservative lawyers. On 11 November 1975, he dismissed the Labor government, appointed Liberal opposition leader Malcolm Fraser as prime minister, and accepted Fraser’s advice to call an election.

Labor was swept out of office in the election, and Australian political life reached a new low from which it has probably yet to recover.

Conserving the Tasmanian wilderness

In the 1960s, people started thinking differently about the Australian environment and how to protect it for the future. The world population was growing fast, air and water quality was getting worse in many cities, fisheries were failing and desert areas were getting larger. Television programs were showing graphically what was happening in other countries with droughts, famines, floods and other natural disasters.

Australians started questioning the old idea that the environment was only important if it could be used for growing food or making money. Sandmining was stopped in New South Wales and Queensland, and people even began asking whether building dams was always a good idea.

Campaigns for the environment started being organised by ‘greenies’—people who believed that the natural environment was valuable even if governments and companies could not make any money from them. A forest is not just a collection of trees—it is a web of living things that need and support each other. With ecosystems, all species are important, but without wiping them out, it is very hard to identify the most important ones—the keystone species.

Environmental education

By the 1970s, environmental educators were encouraging their students to learn about the environment, care about it and take action to protect it. They said that if any two of these things happened then the third would follow.

This photograph of the Franklin river, called Morning Mist by Peter Dombrovskis, helped the campaign against the Gordon-below-Franklin Dam, in Tasmania, to be successful.

Television programs showed what would be lost to the world if action was not taken to protect their environment. These programs gave people knowledge and made them care: action soon followed.

Scientists began to build up case studies. For example, on poor-quality land in the Myall Lakes National Park, Macrozamia plants—cycads—often grow near the Sydney red gum (Angophora costata) rather than with the more common Eucalyptus trees. Angophora trees have holes and hollows where branches have broken off. Termites live in the trees and hollow out the insides. Brushtail possums live in the hollows. They eat the orange outside coverings of the Macrozamia seeds and drop the rest of the seeds near the trees, where they germinate. Macrozamia roots ‘fix’ nitrogen, improving the sandy soil. The trees grow better, providing more heartwood for the termites, and more hollows for the possums. So a forest is definitely much more than just a bunch of trees! When people knew that, they campaigned to stop sandmining there.

Opposing the Gordon-below-Franklin Dam

In the 1980s, an educated environmental movement confronted the Tasmanian Government’s plan to dam the Gordon River in Tasmania. It was proposed that two dams, including the Gordon-below-Franklin Dam, would generate 180 megawatts of hydro-electricity. While this scheme was described as being ‘clean and green’, it would in fact be neither. At the very least, new roads would divide animal habitats, which can lead to extinction of species. Roads also cause erosion and the silting-up of rivers, and they introduce weed seeds.

The new, educated opposition knew about the damage caused by an earlier scheme on Lake Pedder in Tasmania. They had opposed that and lost, but they were determined not to let it happen again. The supporters of the proposed Gordon-below-Franklin Dam knew that if they could get work started, it would be harder to stop and, if they got the work completed, it could never be undone. The stakes were high.

Television programs showed what would be lost to the world if action was not taken to protect their environment.

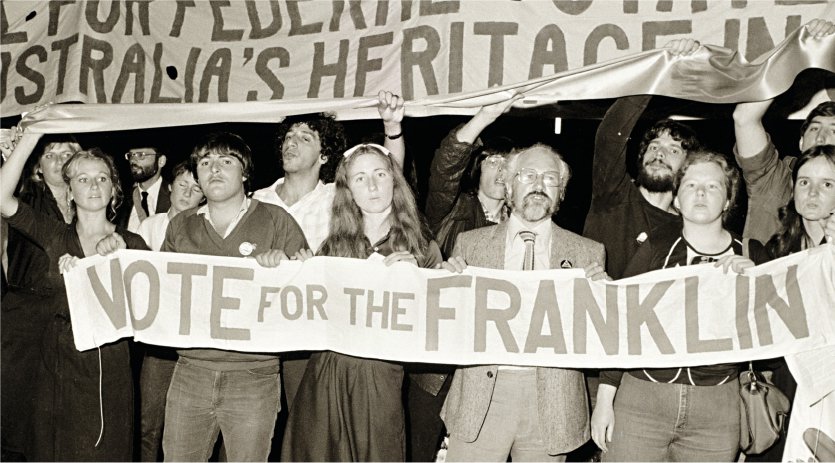

Protesters against the damming of the Gordon River and its effect on the Franklin River, at the opening of a federal Liberal Party election campaign, 1983.

The planned dam would give work to unemployed people, and its continuing operation would provide more jobs. Because of this, about 70 per cent of Tasmanians at first supported building the dam. However, when the film The Last Wild River was shown on Tasmania’s two commercial television stations, and the magical photographs of Peter Dombrovskis and Olegas Truchanas were published, the mood soon changed.

Heavy machinery was being moved in even as a committee of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Paris declared the area a World Heritage site in November 1982. Protesters blockaded the area and, on 14 December 1982, the arrests began. More than 1,200 protesters were arrested and more than 500 were jailed.

With a federal election due on 5 March 1983, action escalated on 1 March. The next day, Dombrovskis’ photograph Morning Mist appeared in mainland newspapers, with the caption: ‘Could you vote for a party that would destroy this?’

The federal Labor Party had promised to preserve the area, and it was swept into power in Canberra. The new Federal Government ordered work on the dam to stop, but the Tasmanian Liberal government kept it going, saying that the Commonwealth had no power to stop it. Finally, on 1 July 1983, the Australian High Court found, by a margin of 4 to 3, that the Commonwealth had the power to prevent work in a World Heritage area.

The environmental scene had changed forever.

Claiming terra nullius

The original justification for British settlers taking up land in Australia was that they thought nobody owned the land. There were no fences, no farms, no boundary markers and no rulers saying, ‘This is my land, go away!’ So the British said it was terra nullius— a Latin phrase meaning ‘land belonging to nobody’.

Did terra nullius apply in Australia? After sailing along the coast with James Cook and landing at only two places—Botany Bay and Cooktown—botanist Joseph Banks concluded that the continent was ‘thinly inhabited’, and so he recommended that a settlement party be sent to Botany Bay.

The first white settlers to arrive in Australia in 1788 encountered a few Aboriginal people living along the coast. When they travelled inland, they did not recognise any plants or animals as bush tucker. Based on their scant explorations, the early explorers decided that the Aboriginal population was very small and lived only on the coastal fringe. In other words, they were convinced there was plenty of terra nullius land for them to use for farming.

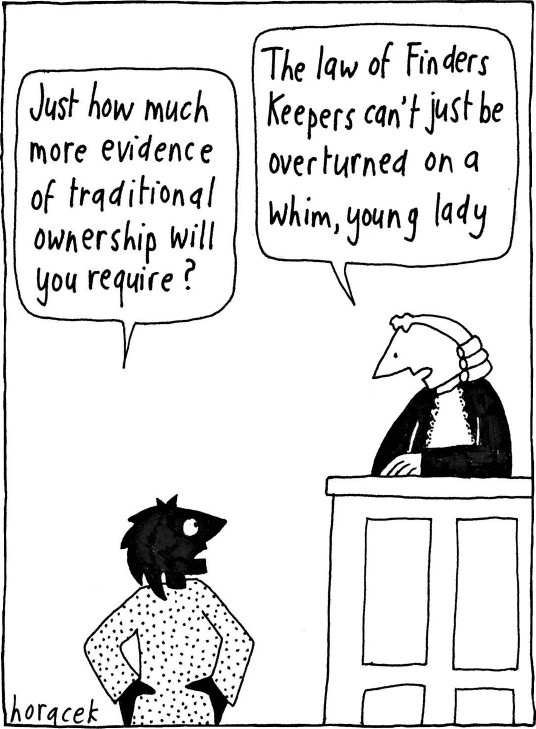

Cartoonists like Judy Horacek helped Australians to see the unfair treatment of Aboriginal people.

Later, when the European settlers realised that Aboriginal people lived throughout Australia, it was too late for them to turn around and go home. An alternative translation of terra nullius could perhaps be ‘finders keepers’—the settlers had found the land and now they were going to keep it.

Even in the early days of white settlement, a few white people sympathised with the Aboriginal people. In October 1840, explorer Edward John Eyre wrote in his journal about the spearing of a white youth by an Aboriginal man:

We should remember … that our being in their country at all is, so far as their ideas of right and wrong are concerned, altogether an act of intrusion and aggression … they cannot comprehend our motives for coming amongst them, or … in remaining, and may very naturally imagine that it can only be for the purpose of dispossessing them … our presence and settlement, in any particular locality, do … dispossess the aboriginal inhabitants.

Very few white Australians in the first 150 years of settlement saw the issues that clearly. An Aboriginal man who spoke in 1853 about going to England to ‘turn em Queen out’ was greeted with smiles but not with nods of agreement. Queen Victoria had the title deeds to her property, but the Aboriginal people had no title deeds to their land—the white people had them instead.

In 1938, a few white Australians, mainly churchmen and academics, supported a Day of Mourning to mark the day in 1788 when the arrival of white settlers changed the lives of Aboriginal people forever. However, most Australians did not think there was a problem. Then, in the 1960s, some white people found their consciences and their voices. Their opponents called them ‘rent-a-crowd’, because the same faces often turned up at protest demonstrations, or ‘demos’, for different causes. That was probably because those same people were protesting about different aspects of a single problem—social injustice.

An alternative translation of terra nullius could perhaps be ‘finders keepers’—the settlers had found the land and now they were going to keep it.

The generation that grew up after World War II lived daily with the fear of nuclear war. The world was interconnected, and ideas and images flowed from one side of it to the other. These young people had seen former colonies win their freedom after World War II, and they saw new hope, new successes—and sometimes new injustices.

They could also see how other countries were fighting old injustices. In the USA, white and black students starting travelling on buses together into the south of the country where there was segregation of African-Americans from white Americans and other racist behaviour. These bus trips were called ‘freedom rides’ because the students were campaigning for the rights of African-Americans. In 1965, a group of students from the University of Sydney decided to organise Australia’s first freedom ride. They travelled in a bus through towns in north-western New South Wales where segregation was practised against Aboriginal people, including barring them from entering cafes, cinemas, theatres, hotels and swimming pools.

At first, the freedom rides and demonstrations changed little, but people were often shocked to find out about the inequalities that Aboriginal people lived under. Change had to come.

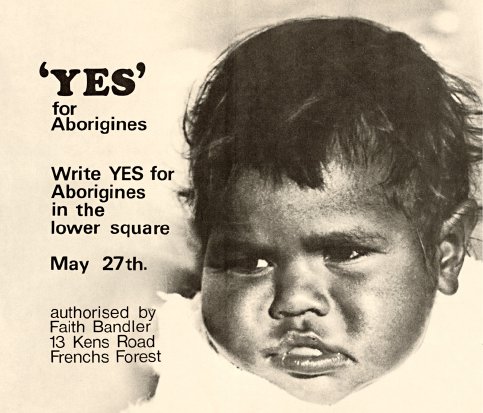

A poster for the 1967 referendum.

From little things

Australian musicians Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody wrote and performed the protest song From Little Things Big Things Grow in the early 1990s. It tells the story of Vincent Lingiari and the Gurindji people’s fight for land rights, reconciliation and a ‘fair go’ for Aboriginal people.

The first step was to make it possible for the Commonwealth to make laws to help Aboriginal people. So, in 1967, the government held a referendum, in which 90 per cent of voters supported the necessary changes to the Constitution.

One of the events that influenced the granting of land rights to Aboriginal people happened at Wave Hill Station in the Northern Territory in 1966. A British pastoral company called Vesteys delayed paying a fair wage to the Aboriginal stockmen and servants who worked on the station. Stockman Vincent Lingiari led 200 of Vesteys’ Aboriginal workers in a walk-off to Wattie Creek. Vesteys finally returned 90 square kilometres of Gurindji land to its traditional owners in 1972.

In 1975, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam symbolically poured soil into Vincent Lingiari’s hands—as well as giving him the title deeds to land at Wattie Creek (Daguragu). The position of many Aboriginal people improved after that.

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pouring soil into Vincent Lingiari’s hands at Wattie Creek, Northern Territory, 1975.

The Aboriginal Land Rights Act (Northern Territory) 1976 set the scene. Then came the Mabo case. This attacked the terra nullius provision. Under terra nullius, the land rights of hunter-gatherers and nomads like the Australian Aboriginal people were regarded as being weaker than the land rights of those who occupied the land and used it for farms and gardens.

However, the Meriam people of Murray Island had gardens, recognised property and had clear boundary markers. So Murray Islander Eddie Koiki Mabo had a winning case: there was no way anybody could claim rights over his people’s land by using the arguments of terra nullius.

The key feature of the case was the decision that the Crown (originally Britain, but now the Commonwealth of Australia and/or the state) held sovereignty and could make rules and laws. All the same, pre-existing ownership could not be wiped out.

In October 2012, the Wik case, which had started in 1993, ended when Federal Court judge Andrew Greenwood granted native title to a 5,000-square-kilometre area of land and waterways in the Aurukun-Weipa area, on the western side of Cape York in Queensland. The decision recognised the rights of the Wik and Wik Way people to camp, hunt and conduct ceremonies across that area. At the same time, they could not stop pastoralists from running their cattle there.

Fighting overseas

Anti-war protests

When Australian troops were sent to the Sudan in 1885, most people agreed with the decision. In 1899, when Australian troops volunteered and were sent to fight in the Boer War, not everybody approved. Australians of German or Dutch origin sometimes spoke out for the Boers, and so did some clergymen, pacifists and a few political radicals. Ordinary Australians sang patriotic songs very loudly, and called the peace-lovers cowards and traitors.

Between 1914 and 1918, pacifists and socialists were treated in the same way as the opponents to the Boer War had been, but there was a lot more opposition to World War I, which helps explain why Australians voted twice against conscription during that time.

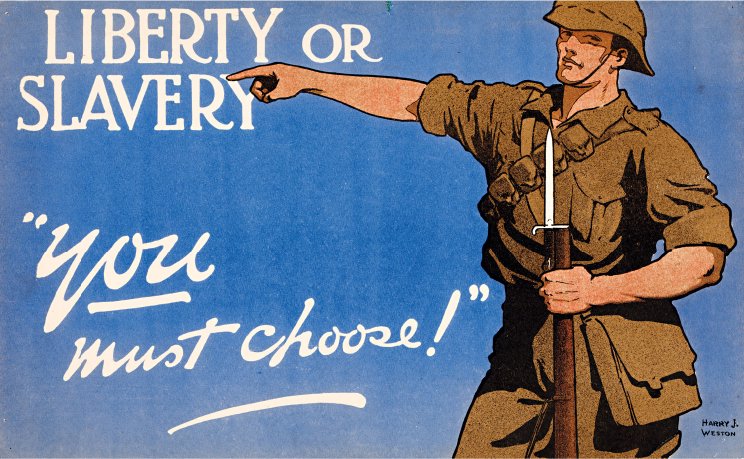

Those who favour war use the loss of freedom as a threat to get the public’s support.

World War II was more complicated. Germany and Russia had signed a peace pact, so Australian communists were told to oppose the war. When Germany invaded Russia in June 1941, the communists suddenly changed sides and supported the war. Most Australians knew about the atrocities committed by the German and Japanese armies, so very few of them opposed the war—and wartime propaganda helped.

The Korean War was fought at a time when many ordinary Australians feared a communist invasion. There was not much opposition to the war in Korea, but the Vietnam War was a very different matter. In that case, it was easy for opponents to say that Australian troops were being used to fight someone else’s civil war. There was also evidence of Australia’s allies committing atrocities, and conscripts were dying in a war which seemed to have little to do with Australia’s needs or welfare.

It was easy to object to the Vietnam War and hard to support it, so supporters fell back on calling the antiwar people ‘traitors’. The main victims were the troops who went, willingly or unwillingly, to Vietnam. They knew they were fighting an unpopular war that many people called ‘dirty’.

The simple fact was that, as in most wars Australia has been involved in, Australia had little choice but to support its allies—in this case America. The argument was that if we did not support our allies, then how could we expect them to support us if we were invaded?

The Gulf Wars

The First Gulf War began in August 1990 when Iraqi troops invaded the small but oil-rich state of Kuwait, on Iraq’s southern border, at the top of the Persian Gulf. The invasion was about oil, power and money, and the USA acted promptly, bringing a large force into Saudi Arabia to help if, as everybody expected, Iraq invaded that country as well.

Unlike the Vietnam War, the coalition troops came from 30 different nations, and their involvement was authorised by the United Nations. While protests against the Vietnam War were fuelled by the fact that it was the first ‘television war’, coverage of the Gulf War was carefully stage-managed. Cameras from US television station CNN recorded and shared images of allied ‘successes’ on the one hand and Iraqi ‘atrocities’ on the other.

Most people in Australia thought their troops were fighting a just war. Fighting in the First Gulf War was well managed, the Iraqis made some tactical errors which could be exploited for public relations purposes, and the war was over too quickly for anybody to organise protests.

The Second Gulf War was different. Australia’s involvement in this war began in 2003. The USA asserted that Iraq was still concealing ‘weapons of mass destruction’, such as nuclear or biological weapons, despite the fact that United Nations Security Council inspectors had not found any. The USA also accused Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein of helping terrorist groups such as al Qaeda, which was linked to the devastating terrorist attacks in New York on 11 September 2001.

When the USA, led by President George W. Bush, could not get backing from the United Nations to overthrow Saddam Hussein, it pushed ahead anyway with a ‘coalition of the willing’, which included Britain and Australia. Many Australians were not so willing to support Prime Minister John Howard involving Australia in what its opponents called an ‘illegal’ war.

Saddam Hussein was deposed and executed, and over 100,000 other Iraqis died, including many civilians. The Second Gulf War officially ended in 2009.

The argument was that if we did not support our allies, then how could we expect them to support us if we were invaded?

The Stolen Generations were Aboriginal children taken away from their parents and families. The people taking the children away believed that Aboriginal culture was inferior to European culture. Many of the children they took away grew up feeling that they had no people, no family, no country and no place. These are all a central part of a continuing culture in Aboriginal society.

Most of the people who took the children of the Stolen Generations from their parents believed they were doing the right thing. When the truth came out, the few participants who were still alive were upset to learn what they had really done.

Looking back now, it seems very cruel to take children away from their parents, so why did white people do it? As well as wrongly believing that Aboriginal people were inferior, many thought that the Aboriginal race would die out. They also believed, again wrongly, that all Aboriginal people had black skin, like many of those in the Northern Territory. So they assumed that any pale-skinned Aboriginal children had ‘white blood’ and therefore needed to be ‘rescued’.

Crowds watching Prime Minister Kevin Rudd giving the Apology to the Stolen Generations, Melbourne, 2008.

The word ‘sorry’ written in the sky during National Reconciliation Week, Sydney, 2000

There is no such thing as an inferior race. Every human race has evolved certain genes that help them to survive in the area in which they live. For example, Europeans have pale skins, which help them to make more vitamin D in the sunless far north of Europe. This vitamin helps our bodies to grow strong bones. However, in Australia, that same pale skin means that white people are more likely to suffer from deadly skin cancers.

There are certainly cultural differences, and cultures are easier to change. There are no inferior cultures and no superior cultures, but some cultural habits also help people to survive in a particular place.

Many white Australians learned the truth about the Stolen Generations from Geoffrey Atherden’s 1986 film Babakiueria, which looked at a world in which the social positions of black and white Australians were changed around. It was gentle satire with a ferocious bite.

A belated apology

On 10 December 1992, a political leader admitted for the first time the truth about what had happened to Aboriginal people in ‘the land of the fair go’. In his ‘Redfern Speech’, Prime Minister Paul Keating spoke of devastation and demoralisation, of dispossession, of the diseases and alcohol that white men had brought, and of the murders white settlers had committed. He celebrated a people who had lived in Australia for about 50,000 years, and who had survived two centuries of abuse.

But Keating stopped short of what was expected in Aboriginal culture: a formal apology for the way in which children were stolen from their families. In 1996, John Howard replaced Keating as prime minister. Howard feared that a formal apology—saying sorry—would start a flood of lawsuits for monetary compensation.

In May 1997, a report called Bringing Them Home was tabled in Federal Parliament, but the Liberal government offered no apology. On 28 May 2000, in the run-up to the Sydney Olympics, 250,000 Sydneysiders walked over the Sydney Harbour Bridge during the Walk for Reconciliation. They hoped to shame the government into action. This was ‘middle Australia’ speaking— ordinary suburban Australians who had learned enough of the harsh truth about the Stolen Generations to know what needed to happen.

Saving the children

Some Aboriginal adults worked out ways to stop the government from taking their children away. For example, children would be encouraged to sit quietly in a hole in the ground, covered by a piece of corrugated iron, when the ‘welfare people’ came to take them away.

In his ‘Redfern Speech’, Prime Minister Paul Keating spoke of devastation and demoralisation, of dispossession, of the diseases and alcohol that white men had brought, and of the murders white settlers had committed.

It should have been enough, but it was not until 13 February 2008 that the next prime minister, Kevin Rudd, tabled a motion in parliament that apologised to Australia’s Indigenous peoples. Rudd publicly apologised to the Stolen Generations, their families and communities, for the laws and policies which he said had ‘inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on these our fellow Australians’.

In many ways, a wrong had finally been righted.

Australians of all ages supported the Apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008.

Changes in political leadership in Australia have often involved claims of treachery. Billy Hughes was a master of the art, and there are still unanswered questions about why Andrew Fisher resigned as prime minister in 1915. There are plenty of similar cases.

Robert Menzies switched to federal politics in 1934 on the promise that Joseph Lyons would resign the leadership to him, but ‘Honest Joe’ Lyons was still leader of the UAP in 1937. Menzies took over when Lyons died in 1939, but Sir Earle Page of the Country Party refused his party’s support to Menzies—a man who had resigned his commission as a militia officer during World War I.

After 1949, Menzies kept his position as prime minister by sidelining those likely to seek the Liberal leadership. William McMahon was blocked by John McEwen, the then Country Party leader, from the Liberal leadership when Harold Holt drowned in 1967. John Gorton won, but then he was beaten by McMahon after McEwen retired. Gorton was elected deputy leader, but was sacked by McMahon for disloyalty just five months later.

After Malcolm Fraser became Liberal leader in 1975, Gorton became an independent politician. He attacked Fraser and denounced the dismissal of the Whitlam government and, in 1983, he congratulated Labor’s Bob Hawke for ‘rolling that bastard Fraser’. Still, politics can sometimes be a funny game and, in the last few years, Malcolm Fraser and Gough Whitlam have become allies in their positions as Australia’s elder statesmen.

Hawke replaced the dumped Labor leader Bill Hayden and then, as when Paul Keating replaced Hawke, there were ill feelings on both sides. Meanwhile, in the Liberal Party, there was continual squabbling between John Howard and Andrew Peacock.

Howard eventually won, and he went on to become a long-serving prime minister, but he and Peter Costello also fought over the leadership during Howard’s later years in office. Life at the top end of politics can sometimes offer very little in the way of trust, honour or loyalty in any party.

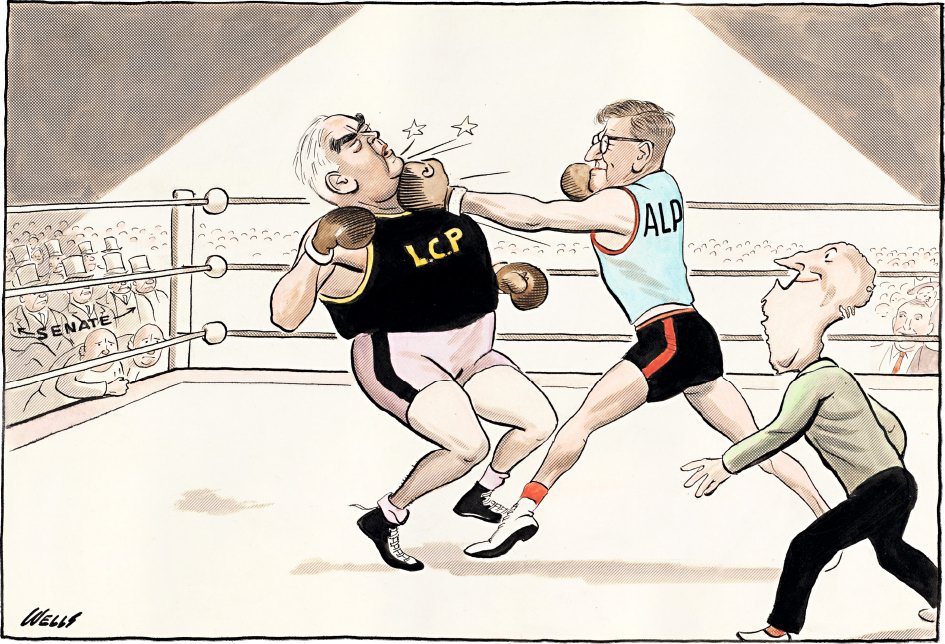

This 1950s cartoon is commenting on the battles between political parties; people within the same party also have fights.

Australia’s first female prime minister

Between 1996 and early 2005, the Labor Party was led by a number of different people—Kim Beazley, Simon Crean and Mark Latham. Then Beazley took over again when the front-runners, Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd, withdrew after Latham resigned as leader.

Kevin Rudd, leader of the opposition, answering questions at the National Press Club in April 2007, a few months before becoming prime minister.

After further squabbling about leadership, Beazley threw all positions open in December 2006. Kevin Rudd was elected leader, with Julia Gillard as deputy leader. A year later, the Labor Party won office. However, nothing else had changed and, before long, leaks and destabilisation were the order of the day.

In hindsight, Kevin Rudd failed to ‘sell’ his policies and to contain the claims of the opposition. Politics is often driven by polls and short-term impressions, and he was seen as a certain loser in the coming August 2010 elections. So, in June 2010, the Labor Party replaced Rudd with Julia Gillard, who became prime minister.

After the August election, Gillard formed a minority government. Three years later, in June 2013, Rudd won back the Labor leadership and again became prime minister, in the lead-up to the 2013 election. Even though she lost the political battle, Gillard will always be celebrated as Australia’s first female prime minister.

Changes in political leadership in Australia have often involved claims of treachery.