Surfboards were very long in the 1940s.

Ask any Australian what we think about sport and the answer will be ‘sports-mad, mate!’. Australia has a good climate for sport, and no news program would be complete without sports news. We play sport and we spend a lot of time watching sport and admiring good players. We even say Australia punches above its weight (a boxing term!) to describe the way Australians have dominated world sports in the past, but will we do so in the future?

Surfboards were very long in the 1940s.

A commemorative carpet for the Melbourne Olympics, 1956.

In 1859, a grain merchant named Evangelos Zappas persuaded the Bavarian-born King Otto I of Greece to support an Olympic festival in Athens. The Greeks removed Otto from the throne in 1862, and so the second Olympiad in that series was never held. The games held in Athens in 1896 are now regarded as the first of the modern Olympics.

The Olympic Games were held in the Northern Hemisphere for many years, but they finally visited the Southern Hemisphere in 1956, when they were held in Melbourne. One reason for the delay was that most competitors came from the Northern Hemisphere and, while aircraft were getting faster in 1956, it still took two or more days to travel from Europe to Australia.

The Hungarians revolt

In 1956, the team from the USA flew to Melbourne by slow, propeller-driven planes, stopping at Hawaii and Fiji, but many other teams travelled by steamship. The Hungarian team, for example, travelled on a Russian steamer, unaware that, back in their capital city of Budapest, Soviet troops were killing unarmed Hungarians who wanted the troops to get out of Hungary.

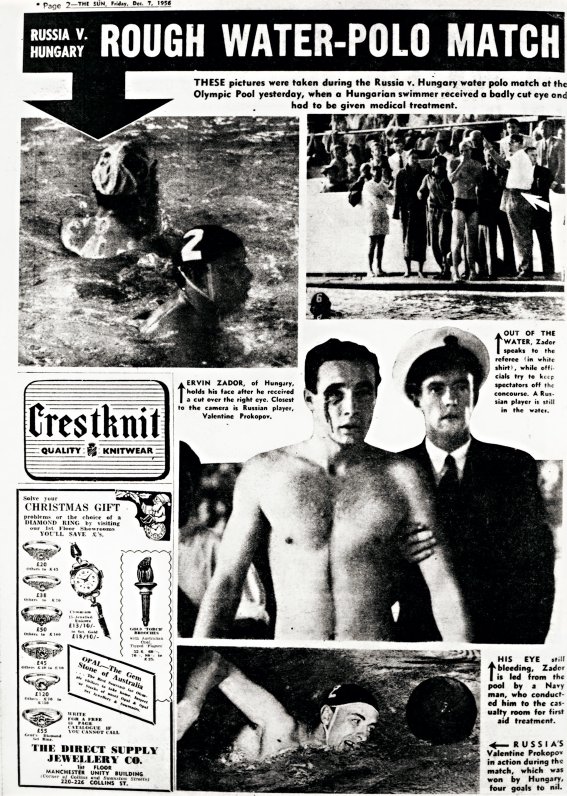

Newspaper coverage of the Hungary versus Russia water polo match in Melbourne in 1956.

The Olympic Games were held in the Northern Hemisphere for many years, but they finally visited the Southern Hemisphere in 1956, when they were held in Melbourne.

The Soviet Union, with a cooperative Hungarian Government, had largely controlled Hungary since 1945, but the Hungarian people were used to revolting against outsiders—Hungary had been an unwilling part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the 1800s. In 1956, the Hungarian Revolution or Uprising came at the end of October and, while it seemed to be successful at first, the Soviet army crushed it in early November. About 2,500 Hungarians and 700 Soviet troops died in the fighting, and almost 200,000 Hungarians fled their country.

In Melbourne, the Hungarian Olympic athletes received the devastating news about what was happening in their country. This led to some interesting incidents when Russia played against Hungary in water polo. Hungary was leading 2–0, when a Russian player hit a Hungarian player in the eye. General fighting broke out among the competitors.

At the end of the game, which the Russians lost 4–0, Valentin Prokopov gashed the eye of a Hungarian player named Ervin Zador with his elbow. That night, there were demonstrations in the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda, when Russian and Hungarian fencers met for a game. By the end of the Games, 34 members of the Hungarian Olympic team had decided not to go home. Some stayed on in Australia, while many ended up in the USA.

Boycotting the Games

Other political problems affected the Melbourne Olympic Games. British forces had occupied Egypt for many years before they withdrew in 1952. When the Egyptian dictator Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal in October 1956, British, French and Israeli troops invaded Egypt to try to topple him. The USA forced the invaders to leave.

Egypt had already withdrawn its Olympic team in August 1956 as a protest over British influence in the Olympic movement. Following Egypt’s lead, Lebanon and Iraq joined the boycott. Later, the Netherlands and Spain withdrew as a protest against the Soviet attack on Budapest.

Then the People’s Republic of China withdrew because athletes from Taiwan would be taking part, and the neutral Swiss boycotted on account of all the political interference! The Swiss later cancelled their boycott, but by then it was too late for them to send a team before the Games started on 22 November 1956.

The friendly Games

In spite of the squabbling, the Melbourne Olympic Games were referred to afterwards as ‘the friendly Games’, mostly because of an idealistic suggestion by 17-year-old Melburnian John Ian Wing. In 1956, he wrote to the Olympic organisers suggesting that the athletes should enter the closing ceremony not as nations but as a mixed group, all parading together.

The number of Australian athletes in the 1956 Olympic Games almost outnumbered the competitors in all our teams from the dozen Olympiads before it. It would be over 40 years before there was such a large Australian team again—at the Sydney Olympics in 2000.

After the USSR and the USA, Australia came third in the medal tally at the Melbourne Olympics, with Hungary fourth. Runners Betty Cuthbert and Shirley Strickland won three and two gold medals, respectively, swimmer Murray Rose won another three gold medals, and swimmer Dawn Fraser took two gold and one silver. Three other swimmers— Lorraine Crapp, Jon Henricks and David Theile— also won gold.

Most Australians loved sport, and Australia’s success at the Melbourne Olympics made them even more sports mad.

The horse events

One part of the Melbourne Olympic Games was actually held months before the Games proper, and in Sweden. Strict Australian quarantine laws meant that all the horse-related events, like show jumping and dressage, could not be held in Melbourne, and so they were held in Stockholm instead.

Cricket

Cricket was being played in the new colony of New South Wales as early as 1804, and there was a cricket ground by at least 1809. In 1810, Governor Lachlan Macquarie took charge of New South Wales and announced his plan to name the streets of Sydney. In the same notice, he gave an official name to what was then called the ‘exercising ground’, the ‘common’, the ‘race course’ or the ‘cricket ground’. It was now to be called Hyde Park.

Around 1825, merchants in Sydney offered cricket bats and balls for sale in the newspapers. Cricket was obviously a popular game by then and, on 2 May 1830, it was reported that ‘a well contested cricket match was played off on the Surry Hills, before a considerable crowd of spectators’.

A souvenir of an England versus Australia cricket match around 1900.

Early representative matches between colonies were difficult to plan. It took time for letters to go back and forth, and then for the teams to travel from one colony to another. The Melbourne Cricket Club and the Launceston Cricket Club played a match in Launceston in February 1851, and the locals won. Soon after, many young men in the colonies rushed off in search of gold, but a return match was played in Melbourne a year later, and Melbourne evened the score.

Shaun Marsh hits a six in the Prime Minister’s XI versus England match, Manuka Oval, Canberra, November 2006.

The first Victoria versus New South Wales cricket match was held in March 1856. Intercolonial matches became more common as steamships ran on fixed timetables between the colonies. By the end of the 1870s, there were regular matches between South Australian, Tasmanian, Victorian and New South Wales teams.

Sheffield Shield cricket

Touring English cricket teams in the 1860s and 1870s established another pattern. Then, in the 1891–92 season, an English team played three tests in Australia. The team was promoted by the Earl of Sheffield, who donated £150 for a trophy for an intercolonial competition, with only New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia involved at first. This became the Sheffield Shield, which has been played ever since, with one rather unfortunate break in tradition.

The break in tradition came in the 1990s. A milk vending company offered money to pay for a cup with the company’s name on it. Cricket traditionalists were appalled, and the non-commercial ABC radio referred to the competition as ‘interstate cricket’ until the name ‘Sheffield Shield’ was reinstated.

The modern game

The idea of a game taking four, five, or occasionally unlimited days, was difficult for some people to accept. This would not have mattered, but some of those people had lots of money and owned television stations, and they wanted to show cricket on their stations.

The Australian Cricket Board stuck with ABC Television, but media tycoon Kerry Packer ‘bought’ players and then set up an almost gladiatorial series of contests to show on his own network. Packer did not like spin bowling and, faced with a continual pace attack, batsmen started wearing helmets.

More and more, decisions were made based on increasing profits rather than benefiting the game of cricket.

Cricket players have a limited life at the top, so Packer’s money attracted many of them. He wanted to present the noise, colour and speed that are found in football matches. He was paying good money, so the players threw away tradition. They wore bright colours rather than whites, and they played in one-day and day–night matches. Audiences enjoyed the games.

Limited-overs matches actually have quite a long history. They date back to 65-overs-a-side matches played in England in 1962, but 50-overs format matches became popular. Because the teams now wore coloured shirts with players’ names on them, there were marketing opportunities of the sort found in baseball and football.

More and more, decisions were made based on increasing profits rather than benefiting the game of cricket. Loud music and often trivial game statistics were brought in. One result was that Packer’s money allowed him to buy the rights to the name ‘Test Cricket’, giving his television channel many more opportunities to sell related products and memorabilia.

Many cricket traditionalists took to watching matches on Packer’s television station with the sound turned off, while they listened to the ABC radio commentary. In recent years, there has been a move to Twenty20, or Big Bash, cricket, and there will probably continue to be changes as the marketers produce new mascots and more exciting team names.

Cricket, once a game played for the enjoyment of the players, is now often a game played for the money paid by live and television audiences. For the elite players at least, the modern game is a far better deal, financially.

The first Australian touring cricket team

The first organised group of Australian cricketers to travel overseas was an Aboriginal team which toured England between May and October 1868. They won or had a draw in 33 of the 47 matches they played in England.

The Aboriginal Australian cricketers who toured England in 1868.

Tennis

Preparing a cricket field in the colonies was easy. A few sheep, goats, or even cattle, were put onto the field to chew down the grass, and the result was a surface that was good enough to play cricket on.

Scythes were also used to cut the grass by hand. A scythe has a large flat blade, mounted on a bent handle. The blade is swept across the ground, neatly slicing off the grass. Few people had the skill to use a scythe reliably, so most of the ‘lawns’ before about 1865 were rough and bumpy, or they were ‘mowed’ by sheep and goats. Ground like that was good enough for cricket but not for tennis, because the ball would bounce at odd angles, and there was the added problem of slippery animal droppings!

The first patent for a mechanical lawnmower ran out in the early 1850s. After that, anybody could sell their version of the cylinder lawnmower, or ‘push’ mower. Once good mowers were available in the shops, people wanted a lawn, mainly because of the prestige. Having a lawn was a sign that you were rich, but boasting about being rich was considered vulgar. The ultimate show of wealth was a lawn tennis court.

In November 1877, an article in The Australian Town and Country Journal calls lawn tennis the ‘newest fashionable game’, adding that it is best played by six players.

The rules of lawn tennis were invented in 1859, just after effective mowers became common in England. The game reached Australia in about 1875 and quickly became popular. Croquet was already a popular sport and, just as British lawn tennis found a home at the All England Croquet Club at Wimbledon, early Australian tennis matches were also probably played on croquet lawns.

In November 1877, an article in The Australian Town and Country Journal calls lawn tennis the ‘newest fashionable game’, adding that it is best played by six players. The illustration above shows a game played with racquets and a ball, across a net higher than some of the players’ heads.

The Davis Cup

Tennis caught on very rapidly in Australia. The Davis Cup competition began in 1899 and, until 1919, Australians competed with New Zealanders as ‘Australasia’. They won the Davis Cup in 1907, 1908, 1909, 1911, 1914 and 1919. Then there was a lull, before Australia beat the USA in 1939. World War II then got in the way.

Sam Stosur in action in Melbourne in 2011.

Australia’s golden era of tennis was from 1950 to 1967. Australia won 15 of the 18 Davis Cups held during that time. Australia also won in 1973, 1977, 1983, 1986, 1999 and 2003, but since then there have been years when the Australian team has even failed to qualify to enter the main draw.

Australians have made their mark on world tennis. They have won Wimbledon many times: from Norman Brookes in 1907 to Lew Hoad in the 1950s; from Rod Laver, Roy Emerson and Margaret Court in the 1960s to John Newcombe and Evonne Goolagong in the 1970s; and from Pat Cash in the 1980s to Lleyton Hewitt in 2002.

In fact, in 1969, Australians won the men’s singles, the men’s and women’s doubles, and shared wins in the mixed doubles. In 1971, the ladies’ final was between two Australians, Margaret Court and Evonne Goolagong.

Over the years, Australia has had an impressive record in Grand Slam tennis tournaments around the world.

Swimming

In the nineteenth century, there were no swimming costumes. This explains why swimming in public between sunrise and sunset was banned until the early 1900s. In the early days of the colony of New South Wales, swimming naked was normal but not always acceptable. Governor Lachlan Macquarie made the following proclamation in 1810:

A very indecent and improper Custom having lately prevailed, of Soldiers, Sailors, and Inhabitants of the Town bathing themselves at all Hours of the Day at the Government Wharf, and also in the Dock-yard, His Excellency the Governor directs and commands, that no Person shall Bathe at either of those Places in future, at any Hour of the Day; and the Sentinels posted at the Government Wharf and in the Dock-yard are to receive strict Orders to apprehend and confine any Person transgressing this Order.

‘Bathing’ included washing, because few bathrooms or baths were available, so many people scrubbed themselves off in the sea, usually choosing a quiet beach. They stayed close to the shore, as many colonial Australians were scared of sharks.

By the 1830s, Sydney was getting larger and it was hard to find a private beach for naked bathing. In January 1833, a Mrs Biggs announced the establishment of her comfortable ‘bathing machine’—a wooden cart on wheels, which was rolled into the sea so the bathers could get changed and bathe in private. According to Mrs Biggs, it could accommodate families ‘on economical terms’. By February, the government forbade bathing in the public parts of the Domain, which would have assisted Mrs Biggs, whose machine was nearby.

At some point, ‘decent’ neck-to-knee costumes came into use, but a ban on daylight swimming remained in place.

Swimming races

The first swimming races held in Australia were called ‘swimming matches’, and they were run in bathing places such as the baths at Woolloomooloo in Sydney. These races were always single-sex events—perhaps because of the competitors’ nakedness. A Mr Robinson owned a bathing machine at Woolloomooloo baths in 1838, and by 1839 they were called Robinson’s Baths.

The very first swimming matches were held on Saturday, 1 March 1845. They included a junior race around two buoys over a distance of 70 yards (64 metres) held at 6.30 in the morning. There was also an all-ages match over 800 yards (730 metres) held at 7 am, which a Mr Burrowes won in 12 minutes and 25 seconds. Given the early starting times, the times recorded and the era, the swimmers were all probably naked.

Competitive swimming soon became popular, and it has remained so. At some point, ‘decent’ neck-to-knee costumes came into use, but a ban on daylight swimming remained in place.

By the early 1900s, a number of municipal councils had given up trying to stop people swimming during daylight hours, and the Bathing Bill of 1894 allowed for mixed bathing (males and females together) during daylight hours on some beaches.

In Victoria, as early as 1892, the people of Port Fairy allowed ‘bathing in company’, with suggestions that it was no more immodest than family bat-and-ball games such as tennis or rounders. The writer added that beachwear was usually far more modest than what you would see in a ballroom.

Swimming at the Olympics

In 1900, one Australian swimmer competed in the Olympic Games in Paris. Frederick Lane won two gold medals—one for the 200-metre freestyle and the other for a 200-metre obstacle race, which involved climbing up and down a pole, scrambling over a row of boats, and diving under another row of boats, as well as swimming 200 metres! By 2012, Australia had won a total of 143 Olympic gold medals, and 58 of them had been won in the pool.

Australians Dawn Fraser, Lorraine Crapp and Faith Leech took all three medals in the 100 metres freestyle in the 1956 Olympics.

In 1912, at the Stockholm Olympics, Australians— competing as Australasia, which included New Zealand— did well in the swimming, although the 100 metres was won by ‘Kahanamoku, a Hawaii island native’ who represented the USA, beating Australian Cecil Healy. Wilhelmina Wylie and Fanny Durack, both of Sydney, took gold and silver, respectively, in the women’s 100 metres. The men’s Australasian team won the four by 100-metre freestyle relay.

Fanny Durack and Wilhelmina Wylie were at first refused permission to go to the 1912 Olympics because the New South Wales Ladies Amateur Swimming Association had banned women from appearing in competitions where men were present. They were finally allowed to go, but Fanny and Wilhelmina had to pay their own way there and back again!

Fanny Durack, a great Australian champion.

Australia began to take notice of its medal-winning swimmers. Frank Beaurepaire, who later became Lord Mayor of Melbourne, would have been a medallist at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm if he had not been disqualified for being a ‘professional’ because he was a physical education teacher. This decision was later overturned, and he won three silver and three bronze medals in the Games of 1908, 1920 and 1924. There were no Olympic Games in 1916 because of the Great War (World War I).

No medallist has appeared at more than three games. Dawn Fraser won four gold and four silver medals in 1956, 1960 and 1964, while Ian Thorpe won five gold, three silver and one bronze in 2000 and 2004. Murray Rose won four gold, a silver and a bronze, while Australia’s other great swimmers include Shane Gould, Leisel Jones, Petria Thomas, Grant Hackett, Libby Trickett, Jodie Henry and Stephanie Rice.

Other Australian Olympic swimmers who became household names in their eras include ‘Boy’ Charlton, John and Ilsa Konrads, Lorraine Crapp, Jon Henricks, Susie O’Neill and Michael Klim.

Australians have certainly made a splash in the swimming pool!

Surfboats were used long before people thought of surfing as a sport. In 1839, the Illawarra Steam Packet Company called tenders for building a surfboat to use for landing passengers and cargo on beaches to the south of Sydney.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, surfboats were often used to get to wrecked ships, and occasionally to land troops on beaches lying between enemy forts. By 1886, a surfboat race was held near Ballina in New South Wales, with four oars and a cox—the person who stands at the back of the boat and steers.

Surf carnivals

Manly, a seaside suburb of Sydney, held what it called its ‘first annual surf carnival’ in March 1907, with ‘shooting the breakers’ (body surfing), fancy diving and ‘other aquatic sports’. The club’s second carnival in December 1907 offered a fancy-dress competition, wading and swimming races, a tug-of-war and a lifeboat demonstration. Another Manly carnival on 25 January 1908 drew an estimated 40,000 spectators, causing traffic jams at the ferry wharf!

By 1919, the surf lifesaving movement was well established and, in November, a postwar ‘Victory Carnival’ at Manly offered events both on the harbour and in the surf. These events included a surfboat race with a prize of 5 guineas (about a week’s pay) for the champion crew. There was also a surfboard exhibition and a display of ‘aquaplaning behind motor speed launches’ on the harbour.

Surfboats heading out through the breakers in a race at Bondi, Sydney.

In 1919, there were no board-riding competitions as we know them today, although first and second places were awarded in a ‘surf board display’ four weeks after the Victory Carnival on the North Steyne section of Manly Beach. The 1919 board was little better than a plank of wood, and it was harder to control than a surfboat.

Surfboards

Surfboards were first mentioned in Australian newspapers in 1840 in an article about Pitcairn Islanders, who rode waves with the help of boards. In 1854, The Sydney Morning Herald mentioned Sandwich Islanders (now called Hawaiians) riding their boards, lying, kneeling or even standing. A Hawaiian surfboard was displayed in Sydney in 1888 but, even in 1911, using a surfboard was still banned on Sydney’s beaches.

A 1913 Sydney Morning Herald article describes the Hawaiian board as being ‘about seven feet long, and eighteen inches wide’ (about 2 metres by 45 centimetres), with a ‘convex top’. The same article mentions that Duke Kahanamoku, the famous Hawaiian sprint swimmer, wanted to visit Australia. He arrived in December 1914.

In January 1915, Sam Walker gave a surfboard demonstration at Yamba, in northern New South Wales. He stood up and even stood on his head on his long, redwood board as he rode in on the waves. Board-riding as we know it had finally reached Australia, but this was during World War I, and so very little happened over the next few years.

On Australia Day 1920, a surf carnival at Manly used no surfboards, but it had two other notable features. First, there was a ladies’ surf race, won by a Miss Andrews of Bondi, with Miss Sly and Mrs Park, both of Manly, taking second and third places. But the great excitement of the day came when Douglas Arkell, captain of the Newcastle Surf Club, lined up for the surf race.

Arkell had been attacked by a shark a year before, and surgeons had amputated what remained of one of his legs. The other swimmers agreed that he should start at the water’s edge, while they began the race at the back of the beach. His final position was not mentioned, but Arkell finished in the first 12!

Women surfers

Between the wars, surfboards became lighter. They were now made from plywood moulded to timber frames, which were shaped and bent in the family copper— a large boiler heated by either a wood fire or gas, which was used for washing clothes. The boards were still very heavy, and the few Australian women who rode surfboards usually did so only as tandem riders, even though women had always ridden boards in Hawaii.

The very first Australian woman to play the passenger role was 15-year-old Isabel Letham. Her father had helped Duke Kahanamoku make a board for demonstrations at Freshwater Beach in late 1914, and Duke took her on several waves, after which she was ‘hooked for life’.

After World War II, the old style of hollow board was replaced by a shorter and lighter one, where a foam or balsa core was covered in fibreglass cloth and resin. Fins were added to give the rider more control of their board, so they could dart in and out of waves, and perform tricks that their parents would have thought impossible.

More girls began to ride boards as well, although Isabel Letham had now been doing so for years. Australian women were soon riding well enough to win competitions. Phyllis O’Donnell won the first women’s World Championship Surfing Title at Manly Beach in 1964, Layne Beachley was seven times Association of Surfing Professionals (ASP) World Champion, and Wendy Botha was ASP Women’s World Champion four times.

Stephanie Gilmore competing at Bells Beach, Victoria, 2010.

The same year that O’Donnell was women’s champion, Australian Midget Farrelly took the first men’s World Surfing Championship, while Nat Young won the world championship in 1966 and 1970. Young was later the ASP World Longboard Tour Champion in 1986 and from 1988 to 1990.

Other outstanding Australian surfers include Simon Anderson, Mick Fanning, Stephanie Gilmore, Taj Burrow, Damian Hardman, Barton Lynch and Mark Occhilupo.

Nat Young is said to have tried to register surfing as an official religion. This says a lot about the way many Australians view the surf.

Nat Young is said to have tried to register surfing as an official religion.

One of the earliest newspaper references to organised athletics in Australia described the ‘Border Games’ in August 1850 on a Melbourne racecourse. The events included standing and running jumps, quoit throwing, a sprint, a hurdle race, ‘putting the heavy stone’ and hammer throws. However, after the light hammer flew into the crowd, the stewards stopped that event.

The Bendigo Easter Sports in 1856 included running races, with prizes of £2 and £5 (one or two weeks pay), watches and rings. There was also wrestling, ‘the manly art of self-defence’ (boxing), catching greased pigs and climbing greased poles!

Spot the people getting in free to the first gathering of the Bendigo Caledonian Society, 2 January 1860.

As well as the usual running races, Melbourne’s ‘Caledonian Gathering’ in 1859 included playing the bagpipes, stone throwing and Highland dancing. And, in 1862, the games at the Copenhagen Grounds in Ballarat featured a novelty race over 100 yards (91 metres) between two ladies in voluminous crinoline dresses!

‘Pedestrians’

In the 1840s and 1850s, the term ‘pedestrian’ referred to athletes like the ‘Flying Pieman’, who performed challenges such as ‘walking 100 miles in 22 hours’.

The Flying Pieman was William Francis King. He once accepted a bet to walk from Sydney to a mile beyond Parramatta and back again—a distance of 32 miles (51 kilometres)—in six hours. He finished in five hours and 59 minutes, and observers said that he was ‘in no way distressed’. Another time, he carried a dog that weighed 70 pounds (32 kilograms) from Campbelltown to Sydney between the hours of 12.30 am and 8.40 am, finishing at 8.20 am, with 20 minutes to spare.

The Flying Pieman

Sydney’s ‘Flying Pieman’, William Francis King, died in 1873. His memory lives on in the legends about his athletic ‘pedestrian’ feats. There is an unlikely legend that he sold pies to ferry passengers at Circular Quay, and then walked fast enough to welcome them at the end of their journey to Parramatta, 25 kilometres away, and sold them more pies!

Australia has had other ‘eccentric’ athletes, including Cliff Young, who started running ultra-marathons in his sixties. He trained in overalls and gumboots, and claimed to have developed his shuffling style of running while chasing sheep, sometimes day and night, on the family farm. He won the first Sydney to Melbourne race over 875 kilometres in 1983, mainly because he went without sleep and overtook the other runners as they slept. He took five days, 15 hours and 4 minutes to complete the run.

Young was from Victoria, and many of Australia’s best runners have been Victorians. That state also offers the richest race for men sprinters, the Stawell Gift. Originally run over 130 yards (118.9 metres), it is now run over 120 metres, and it uses a complicated handicap system. Betting is allowed, as it was on the first women’s running championship held in Victoria in 1908, 30 years after the first Stawell Gift.

Robert de Castella winning the Commonwealth Games Marathon, Brisbane, 1982.

Female athletes

Women athletes had to wear clothing that was regarded as decent by polite society, so at first it was hard for them to record fast race times. In April 1908, Ivy Evans of Bendigo was declared the ‘champion lady pedestrian of the Commonwealth’ after she beat Mrs Isa Bell of Albert Park in Victoria in a number of running races.

A women’s hurdles race, Sydney, March 1931.

Women did not represent Australia in athletics at any Olympic Games until 1936, when high jumper Doris Carter took part. In 1948, Australian women won one silver and two bronze medals on the track, while in 1952 they won three gold medals and one bronze and, in 1956, four gold medals and three bronze.

There have been a number of successful Australian male runners, including marathon runner Robert de Castella, long-distance runners Ron Clarke and Steve Moneghetti, and middle-distance runners Herb Elliott and John Landy.

Women athletes had to wear clothing that was regarded as decent by polite society, so at first it was hard for them to record fast race times.

Outstanding Australian female sprinters include Betty Cuthbert, Marjorie Jackson and Shirley Strickland, who each won two or more Olympic gold medals in individual events; as well as Melinda Gainsford-Taylor and Olympic gold medallist Cathy Freeman.

Over the years, Australia has had many Aboriginal sporting champions. Nova Peris-Kneebone won Olympic gold as a hockey player in 1996, as well as gold in a World Cup and two Champions Trophy hockey competitions. She also won two gold medals in the 1998 Commonwealth Games as a sprinter.

Four Aboriginal men have won the Stawell Gift sprinting race, while Percy Hobson won a gold medal for high jumping at the Commonwealth Games in 1962, and Benn Harradine won gold in the 2010 Commonwealth Games in the discus event.

In 1971, Evonne Goolagong won her first Grand Slam tennis championship. Five years later, she had another 11 Grand Slams to her credit, and was the world’s top woman tennis player. By the end of her career, she had won 13 Grand Slam titles—seven individual titles and six titles in mixed or women’s doubles events.

There have been many famous Aboriginal boxers, including Tony Mundine, his son Anthony Mundine, and Lionel Rose. Rose became world bantamweight champion in 1968, but he refused to fight in South Africa in 1970 because, under South Africa’s apartheid rules which discriminated against black people, he could only be admitted into the country as an ‘honorary white person’.

Another Aboriginal sportsman who spoke out against racism was Charles Perkins, who led the 1965 freedom ride. He was a professional soccer player who had turned down an offer from the British team Manchester United. Instead, he returned to Australia and played for the Adelaide Croatia Soccer Club, before becoming captain-coach of the Pan-Hellenic team in Sydney. Later, he was a senior public servant and public figure.

Cathy Freeman

Cathy Freeman is one of the best known and most admired of Australia’s Aboriginal sporting stars. She was only 16 when she won her first Commonwealth Games gold medal in Auckland in 1990. Freeman was the first Aboriginal person to win gold at a Commonwealth Games, and one of the youngest medallists.

She had always been a sprinter as a girl growing up in Mackay in Queensland, but at 14 she moved to Brisbane and then, on a scholarship, to Toowoomba, before playing her part in the four by 100-metre relay in the 1990 Commonwealth Games. She ran well, but not at medal standard, at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992, but at the 1994 Commonwealth Games she took gold in the 200- and 400-metre sprints, and silver in the four by 100-metre relay. While her team came first in the four by 400-metre relay, it was later disqualified.

Cathy Freeman is one of the best known and most admired of Australia’s Aboriginal sporting stars.

Cathy Freeman on the blocks at the start of a race in 1997.

At the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, Freeman took silver behind France’s Marie-José Pérec in the 400 metres. Her times improved as the Sydney Olympics got closer, but she was troubled by injuries, and there was also the pressure of being the home-town favourite.

Freeman had one very stressful moment at the start of the Sydney Olympic Games. She had been selected to light the flame in the Olympic cauldron. The torch was passed to her by six women, all former gold medallists. Freeman stepped forward as required, and then the machinery that was designed to lift her up to the cauldron ground to a halt. The official explanation was that there was a computer glitch. For four minutes, Cathy Freeman kept her cool as Australians, and television viewers watching the opening ceremony around the world, held their breath until the cauldron was finally lit.

Pérec pulled out of the 400-metre race, claiming to have been harassed. Then, on 25 September 2000, Australians again held their breath for the 49.11 seconds it took Cathy Freeman to win Olympic gold.

Freeman ran a lap of victory carrying both the Australian and the Aboriginal flags—a fitting gesture of reconciliation.

By 1829, members of the military garrison in Sydney were playing football in the barracks square. According to The Sydney Monitor, this was an old Leicestershire custom. It clearly caught on, because in 1832 an angry citizen complained to The Sydney Herald about youths playing football in Hyde Park on a Sunday ‘during the hours set aside for Divine Service’.

In 1837, merchants were selling ‘Foot Balls’ in George Street in Sydney. By the 1850s, the churches were praising the idea of having ‘a healthy mind in a healthy body’, and so playing sport on a Sunday became acceptable.

‘Aussie Rules’

Only one successful sport has been invented in Australia. Australians in states where it is less popular often call the game ‘Rules’ or ‘Aussie Rules’, or even ‘aerial ping-pong’. In states where the game is popular, it is often just called ‘footie’. Officially, it is AFL—after its governing body, the Australian Football League.

A cricketer named Tom Wills started the game in 1858 in Melbourne. By year’s end, there were rules and a number of games had been played, although there was a fair amount of adjustment later. At first, there was no time limit, and the first team to score two goals was declared the winner.

A 1908 souvenir program from a carnival.

The earliest references to Aussie Rules football clubs appeared in Australian newspapers in 1858, and by 1859 there was enough interest in the game for a sample of the rules-in-progress to be published in The Argus. These rules included: scoring by passing the ball between the posts without touching either one; scoring a fair goal by forcing a ball between the goalposts in a scrimmage; and prohibiting tripping, holding and hacking, but allowing pushing with the hands or body when a player was moving fast.

Other rules said that the ball might be picked up at any time, but could not be carried further than necessary for a kick and that, in the absence of umpires, the two captains were the sole judges of infringements.

By 1866, the rules had been revised several times, clubs had been started in South Australia, Queensland and Tasmania, and an oval ball was being used rather than the round ball favoured in the rather similar Gaelic Football. The first Australian Rules competition was based in Melbourne and was called the Victorian Football Association, after it was formed in 1877.

Old-style ‘Aussie Rules’: an 1880s player and ball.

In September 1869, a match between 16 members of the North Adelaide Club and 16 from the Woodville Club ran from early in the afternoon until sundown. It seems they did not change ends, because a very strong wind favoured North Adelaide all afternoon, and the only goal of the match went to them.

After a reasonably successful visit by an English team in 1888, the game might have gone international, but that failed. The Victorian Football League formed as a breakaway group in 1896, and their competition started in 1897.

Two things changed over the years: the rules and the methods of play. A writer in The Argus in 1910 commented that there was little that was original in the game at that time. He continued:

The first code of rules was drawn up in 1866, but there have been many changes since then … though it may seem strange to speak thus of ‘ football,’ it is possible for a man to be a good player without kicking the ball at all. Handball has been developed to such an extent that the ball frequently travels between half a dozen players without reaching the foot at all.

Very few people questioned the changes, because they made for a more exciting game and that brought the crowds in.

Rugby

At the very end of 1863, news reached Australia that British public schools Eton, Harrow, Westminster, Winchester and Rugby had agreed to have one general set of rules for ‘football’. They intended to play on Saturday afternoons.

By 1866, a fierce match—with mauls, touchdowns and kicked goals—took place in Sydney between two teams called ‘University’ and ‘Military and Civil’. The game, in late August, would be the last of the season, as the ground was to be prepared for the coming cricket season. This must have been a Rugby Union game, as Rugby League did not break away from Rugby Union until 1908.

Before long, watching football became a popular spectator sport. By 1884, the term ‘barracker’ was known, and the first person described as a barracker was a retired team vice-captain. For a few years, ‘barracker’ seems to have been a popular Victorian term, but it slowly found its way to Tasmania and South Australia and, by 1889, ‘barracking’ at the cricket was heard of in the Hunter Valley in New South Wales.

Lucas Neill in action for the Socceroos in a match against Malaysia, Canberra, 2011.

The modern game

Modern football, whatever the code—Australian Rules, Rugby Union, Rugby League or soccer—is quite unlike what it was in the past, even as late as 1970. The changes have mainly involved money and marketing, and began when Kerry Packer started luring English and Australian test cricketers by offering them more than ten times what they had been paid for a series of five test matches.

If football players wanted professional pay, the clubs had to be run professionally. The rights for everything from media coverage to team shirts and memorabilia also had to be managed professionally. Teams based on suburbs became franchises that could be moved around, and leagues became national institutions. The VFL became the AFL in 1990, and the South Melbourne team became the Sydney Swans, while Fitzroy became the Brisbane Lions.

Tradition and nostalgia may have been ignored, but the football codes continued to thrive.

Before long, watching football became a popular spectator sport.

There are two ways to win a yacht race: by being the most skilled sailor and/or by having the best boat. Yachting has always been a sport for the rich because, at the extremes of big-boat yacht racing, rich men ‘buy’ their designers, their skippers and their crews.

The America’s Cup was named after the schooner America, the first vessel to win the race, in 1851. A syndicate from the New York Yacht Club (NYYC) built the schooner and took her to England to race against British yachts. In a race against the entire Royal Yacht Squadron around the Isle of Wight, America won by eight minutes and the syndicate took the Cup back to New York.

In 1857, they donated it to the NYYC under a deed of gift, which was amended in 1881 to make it very hard for foreigners to ever win the Cup. Challengers had to sail their yachts to where the race was held, and there were other restrictions on the length of yachts and the sail area. In the 24 challenges before 1983, careful use of the rules had ensured that every foreign challenger lost.

Australia was extremely pleased with the result of their 1983 challenge for the America’s Cup.

In 1887, Scottish challenger Thistle was made to a secret design. When the vessel was dry-docked before the race, her hull was draped with cloth to hide the details. In 1895, the Americans had their new boat Defender built inside a hangar, and launched it at night to keep its design secret.

Between 1899 and 1930, Sir Thomas Lipton, a very rich tea merchant, made five unsuccessful challenges, but he made his brand of tea popular in Britain! There were challenges in 1934 and 1937, before a gap of 21 years. By 1958, a new standard for yachts had been established, and the British challenger that year was in the new 12-metre class. And, by then, challengers did not have to sail all the way to America!

Australian challengers

A yachting ‘class’ is a set of rules, limits and specifications, inside which boats may be designed. That means a naval architect anywhere can look at the rules and make a design that is within them. All of a sudden, Australia was knocking at the door of the NYYC. The 1962 and 1970 challenges were funded by Sir Frank Packer, a rich publisher and the father of media mogul Kerry Packer. Another Sydney-based challenge was sailed in 1967. All three failed.

Alan Bond now entered the competition. Bond was an extremely rich and controversial Western Australian entrepreneur, who would later go bankrupt and serve time in jail for fraud. Many Australians now regard him as a rascal, and some did even then.

Bond’s team launched unsuccessful America’s Cup challenges in 1974, 1977 and 1980, winning just one race and losing 12. Each challenge was a ‘best-of-seven’ competition. With that history, the Americans were probably not very worried about the 1983 challenge. However, Bond arrived with a golden spanner that he said would be used to unbolt the cup. He was playing mind games—but the Americans were better at it!

The Americans discovered that Bond’s yacht, Australia II, featured marine architect and designer Ben Lexcen’s winged keel, and they began to worry. They complained that the Australians were hiding their design, despite the precedents set by Thistle and Defender.

Australia II crossed the line 41 seconds ahead of the American boat, with the boxing kangaroo flag flying and Australian band Men at Work’s song Down Under belting out.

The gentlemen of the NYYC could not get the design thrown out, the media were not allowed to examine the keel, and scuba-divers failed to photograph it. The NYYC had no alternative but to start sailing. A few days later, Australia II was down three races to one.

Dennis Conner, the American skipper of Australia’s rival Liberty, was not the only one playing games now, but he hardly needed to. He just needed one more win and it would all be over. The Australians had suffered equipment failures early on, but they were now on top of those issues, and they soon levelled the score at three wins each.

Conner was still feeling good when he took a lead of two minutes in the final race on 26 September 1983. Then things came unstuck. By the next mark, he was less than a minute ahead and, at the final mark, he trailed by 21 seconds, and Australia II was pulling away.

An aerial view of Australia II off Fremantle during trials for the America’s Cup in 1983.

Australia II crossed the line 41 seconds ahead of the American boat, with the boxing kangaroo flag flying and Australian band Men at Work’s song Down Under belting out. In Perth, Prime Minister Bob Hawke declared, ‘I tell you what, any boss who sacks anyone for not turning up today is a bum!’

It was a day for sports-mad Australians to rejoice.

Sailing solo around the world

Most people say that the first person to sail around the world was Ferdinand Magellan, but he died in the Philippines and just four out of the 55 crewmen from his ship Trinidad actually made it all the way back to Portugal in 1522. Sailing around the world was a dangerous business in the 1500s.

By 1589, Martin Ignacio de Loyola had gone around the world twice, and by 1711 Englishman William Dampier had been around the world three times, including two visits to Australia. The cook from Dampier’s ship died near Shark Bay and was buried there: sailing around the world was still pretty dangerous.

Joshua Slocum started the new and more dangerous tradition in the 1890s of sailing around the world alone, and over 200 people have done so since then.

Between 1766 and 1769, a Frenchwoman named Jeanne Baret sailed most of the way around the world on Louis Antoine de Bougainville’s Étoile. She was disguised as a boy, as women were not welcome on sailing ships at that time. She left the ship in Mauritius and reached Paris, probably in 1775.

In the 1800s, more ships sailed to Australia, and sailing around the world became more common and much safer. Joshua Slocum started the new and more dangerous tradition in the 1890s of sailing around the world alone, and over 200 people have done so since then.

In 1988, Australian Kay Cottee did it the hard way, by going the whole way without calling into any ports, and thus becoming the first woman to sail non-stop around the world. Then in 1999, Jesse Martin sailed back into Melbourne after a trip around the world. He was just 18.

Jessica Watson on her yacht after completing her solo voyage around the world, 15 May 2010.

Jessica Watson was 11 when she decided to be the youngest person to sail alone, non-stop and unassisted, around the world. She completed her journey on 15 May 2010, and she turned 17 just three days later. She was later made the 2011 Young Australian of the Year.

At the end of 2011, Watson skippered the yacht Another Challenge in the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race with the youngest-ever crew, none of whom was over 22.

Other sporting highlights

From archery to zorbing, there are many sports in which Australia has produced champions. Some make the headlines and become household names, but many others do not.

Team sports

Australian basketball gets good media coverage, partly because of the way it is presented and sold to the public. Australia’s male basketball team, the Boomers, have struggled to reach medal level at the Olympics, but the women’s team, the Opals, won bronze in London in 2012, after winning silver at three earlier Olympic Games.

Australia’s hockey players have achieved even more impressive results. Both the Australian women’s and men’s hockey teams regularly play in the finals at the Olympic and Commonwealth Games, and also in world-class events such as the Hockey Champions Trophy. The men have won six bronze, three silver and one gold medal at the Olympics, as well as the last five Champions Trophies. The women have won three Olympic gold medals and six Champions Trophies.

The Australian men’s water polo team finished seventh at the London Olympics in 2012, while the women’s team came fourth at the Athens Olympics and won bronze medals at both the Beijing and London Olympics.

Australia’s netball teams have also dominated the world in the game for many years. Netball has a huge following in Australia, both as a spectator sport and as a highly popular recreational game. Perhaps because it is a sport predominantly played by women, it does not get the recognition or coverage that men’s sports such as the various codes of football receive.

Individual sports

Another sometimes underrated sport is squash. Australian squash player Heather McKay won 16 British Open and two World Open championships between 1962 and 1979. Five of her British Open wins were against other Australians.

And cycling in Australia goes back at least to the 1890s, when people realised that a bicycle needed less space to store and was easier to keep than a horse. Many people regularly travelled long distances by bicycle, and some bush workers used their bicycles to carry heavy loads, and then had races on them when they got to their destination.

‘Oppy’ in his prime in the 1920s.

Francis Birtles rode bicycles all around Australia but, while Birtles was no racer, Hubert Opperman was. ‘Oppy’ began his working life delivering telegrams by bicycle, and he went on to win many endurance races. He was later knighted, and he served as a federal cabinet minister in the Menzies government. Like Opperman, Cadel Evans has competed in the Tour de France but, unlike Opperman, Evans won the event, in 2011. Anna Meares, Robbie McEwen and Ryan Bayley are also high-achieving Australian cyclists.

Australia has also produced champion motorcyclists, rally drivers and racing drivers, all of whom learned their skills on Australian roads. They include Formula One racing champion Sir Jack Brabham, and world champion motorcycle riders Casey Stoner and Mick Doohan.

Despite its mainly warm climate, Australia has also bred winter sports champions such as snowboarder, Torah Bright, who won a gold medal in the 2010 Winter Olympics, and the very lucky and tenacious Steven Bradbury, who won a gold medal in the 1,000-metre short-track speed-skating event at the 2002 Winter Olympics.

This is just a small selection of some of Australia’s outstanding sporting achievements.

Last man standing

Australian speed skater Steven Bradbury won his gold medal at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City in the USA in unusual circumstances. When all of the skaters in front of Bradbury fell over, one after another, all he had to do was to stay on his feet and glide past the finishing line. His win, which showed that persistence pays off and that sometimes it is enough just to be the last man standing, led to the introduction of a new Australian phrase— ‘doing a Bradbury’!

Related newspaper articles of the time

Near the end, descriptions of swimming costumes on sale in 1950.

Some early history of surfing and the use of boards in rescues.

Explore more