DATE: 1642.

WHAT IT IS: The excised right middle finger of the Italian astronomer, Galileo Galilei.

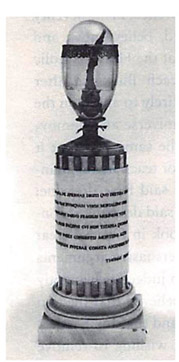

WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE: The preserved finger is gray and measures 3.5 inches long and .79 inches wide at its maximum width. The finger is contained in a glass casket set on a cylindrical alabaster base on which is an inscription in Latin by the eighteenth-century astronomer Tommaso Perelli that reads: “This is the finger with which the illustrious hand covered the heavens and indicated their immense space. It pointed to new stars with the marvelous instrument, made of glass, and revealed them to the senses. And thus it was able to reach what Titans could never attain.”

“E pur si muove! ” (And yet it does move!)

— Quote attributed to Galileo Galilei

after recanting his belief that

the earth revolves around the sun

Since ancient times, sages pondered the enigmas of the physical universe, but the idea that the earth moved in a circular orbit around the sun seemed preposterous to any logical mind. After all, people standing on the earth’s surface feel no such movement, and each morning the sun is seen to rise in the east, climb to the zenith, then move west where it sets in the afternoon. Moreover, any statement to the contrary would contradict the biblical notion of the earth as the center of creation. For making precisely such a statement, the tribunal responsible for promoting the Catholic faith, the Holy Office, put the seventeenth-century scientist Galileo on trial for heresy. After weighing the evidence, the cardinals rendered their condemnation:

We say, pronounce, sentence, and declare that you, Galileo, by reason of these things which have been detailed in the trial and which you have confessed already, have rendered yourself according to this Holy Office vehemently suspect of heresy, namely of having held and believed a doctrine that is false and contrary to the divine and Holy Scripture; namely that the Sun is the center of the world and does not move from east to west, and that one may hold and defend as probable an opinion after it has been declared and defined contrary to Holy Scripture. Consequently, you have incurred all the censures and penalties enjoined and promulgated by the sacred Canons and all particular and general laws against such delinquents. … We condemn you to formal imprisonment at our pleasure.

Facing life imprisonment, Galileo publicly recanted his alleged heresies and wisely avoided a lengthy sojourn in a dingy dungeon. His sentence was commuted to house arrest, carried out first at the home of his friend the archbishop at Siena and then at his villa at Arcetri, near Florence, where he died several years later, on January 8, 1642.

An artist's rendition of Galileo in prison.

For the scientist who endeavored to tear down the musty curtains of antiquated beliefs and let in the light of solid mathematical reasoning, Galileo’s condemnation was a fall from grace. But the great Renaissance man was a hapless victim of his times and locale; to publicly promote a scientific understanding of nature that was deemed contrary to the Bible could only invite the wrath of the Inquisition.

Galileo Galilei, the Italian astronomer, physicist, philosopher, and mathematician, was born on February 15, 1564. In 1588, at the age of twenty-four, he was appointed a professor of mathematics at the University of Pisa, then in 1592 received the same appointment at the University of Padua, where he remained until 1610. During the time he held chairs in mathematics, Galileo carried out pioneering work in mechanics, magnetism, thermometry, and astronomy. He devised the fundamental law of falling bodies, fabricated a compass, mathematically accounted for tides by applying certain concepts of Copernicus, and used a telescope he built to probe the heavens and make numerous discoveries about the planets, the Milky Way, and the moon. But around 1612, with his affirmation of Copernicus’s sun-centered universe, he began to stir the anger of philosophers and theologians and provoke a response that would culminate in a personal crisis.

Galileo lived during an era when reasoning and independent inquiry were beginning to supplant traditional religious dogma and superstition. With humanists, inventors, writers, artists, explorers, and scientists of the likes of Erasmus, Gutenberg, Shakespeare, da Vinci, Michelangelo, Columbus, and Copernicus carrying out important and revolutionary work, the Western world was aflame with invigorating ideas, exciting discoveries, and pioneering achievements. During this time of reawakening, known as the Renaissance, which began in Florence at the start of the fourteenth century and lasted through the end of the seventeenth century, people began to look at life in different ways, to question old sacrosanct doctrines of faith and attempt to comprehend nature in ways that seemed to blaspheme the Bible. Whereas the teachings of the Church had previously been accepted without question, the rebirth of free inquiry led people to question the Church’s teachings and search instead for truths based on empirical observation. After the long intellectual and creative dormancy that had characterized the Dark Ages, the free-thinking spirit that had animated ancient Rome and Greece was reinvigorated.

As a free-thinking and autonomous scientist, Galileo ran into problems through his investigations. He contradicted conventions such as the Aristotelian notion that bodies of different weights fall at a speed in proportion to their weight in favor of the conclusion that all bodies, no matter what their weight, fall to the ground at the same speed. His probing of the heavens—in which he observed sunspots, noted that the planets showed phases, and found that moonlight was not emitted by the heavenly body itself but was the reflection from its surface of the sun’s light—led him to affirm Copernicus’s heliocentric hypothesis.

The idea of a sun-centered world in which the planets revolve around the bright celestial body was actually a Pythagorean doctrine that the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus had taken up in his posthumously published De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Concerning the Revolutions of the Heavenly Bodies). After Galileo embraced the sun-centered hypothesis, it spread through the Western world. Proponents of the Aristotelian system, in which a fixed earth stood as the center of the universe, were now in danger of being discredited, and they conspired to condemn Galileo as a promulgator of blasphemy. Galileo warned that if people were made to feel that belief in the laws revealed by science was sinful, it would ultimately be harmful, and he zealously attempted to convince Church authorities that his theories did not endanger ecclesiastical beliefs because they were only theories. Acting in his own best interests, however, he denounced Copernicus’s writings, which the Holy Office put on the list of prohibited material until its “errors” could be removed. Galileo continued to devote himself to further scientific study though, and in 1632, his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems was published, which was in effect a renewed argument for the Copernican heliocentric system. Although the Roman Catholic censors gave Galileo their consent to publish the book, its support of the Copernican system caused an uproar. The Pope charged that he had been deceived into allowing its publication, and this accusation ultimately led to Galileo’s prosecution by the Inquisition. The Inquisition held that a 1616 decree forbade Galileo from expounding on the theories of Copernicus, and it produced a document (whose authenticity has been the subject of debate) stating the proscription. The Inquisition banned all Galileo’s works and ordered him imprisoned. Forced to betray his own knowledge and acknowledge a false truth, Galileo formally recanted:

I, Galileo, son of the late Vincenzo Galilei of Florence, being seventy years old … swear that I have always believed, believe now, and with God’s help, will in the future believe all that the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church doth hold, preach, and teach. But since, after having been admonished by this Holy Office entirely to abandon the false opinion that the Sun is the center of the universe and immovable, and that the Earth is not the center of the same and that it moves, and that I was neither to hold, defend, nor teach in any manner whatsoever, either orally or in writing, the said false doctrine; and after having received a notification that the said doctrine is contrary to Holy Writ, I wrote and published a book in which I treat this condemned doctrine and bring forth very persuasive arguments in its favor without answering them. I have been judged vehemently suspected of heresy, that is of having held and believed that the Sun is at the center of the universe and immovable, and that the Earth is not at the center and that it moves. Therefore, wishing to remove from the minds of your Eminences and all faithful Christians this vehement suspicion reasonably conceived against me, I abjure with a sincere heart and unfeigned faith all these errors and heresies, and I curse and detest them as well as any other error, heresy, or sect contrary to the Holy Catholic Church. And I swear that for the future I shall neither say nor assert orally or in writing such things as may bring upon me similar suspicions; and if I know any heretic, or one suspected of heresy, I will denounce him to this Holy Office, or to the Inquisitor or Ordinary of the place in which I may be.

The middle finger of Galileo's right hand set in a glass bowl mounted on an alabaster stand.

Although his voice in scientific matters continued through his writing—his treatise on solid bodies and accelerated motion, Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Concerning Two New Sciences, was published in Holland in 1638—Galileo Galilei was physically set apart from the world, symbolically banished from civilization in the commutation of his prison sentence to house arrest. After eight long years of confinement at his Arcetri villa, Galileo died on January 8, 1642, at the age of seventy-seven. For a scientist who was instrumental in vanquishing antiquated ideas about the world and supporting scientifically based theories that attempted to explain the world rationally, Galileo’s last years were a sad chapter in a great life. His body was placed in a small room in the Chapel of Saints Cosmas and Damian, but a quirky fate awaited the corpse.

The ecclesiastical condemnation precluded Galileo from having a proper funeral in the main chapel of the church where he was buried, and this later, evidently, caused some of his compatriots to feel remorseful. Vincenzo Viviani, who as a teenager attended Galileo in the last few years of his life and went on to become an engineer, provided in his will for a tomb to be built in the main chapel as a fitting sanctuary for the ostracized scientist, and on March 12, 1737, Galileo’s remains were moved to the more appropriate spot for re-interment. During the transport a scholar, Anton Francesco Gori, severed the right middle finger of Galileo. The corporeal relic, which became an object of veneration, was later displayed at the Laurenziana Library, then, for a period of time beginning in 1842, in a Galilean rotunda inside the Museum of Physics and Natural History along with other artifacts related to Galileo’s life and work.

Galileo had led a very distinguished and troubled life. He made numerous extraordinary scientific contributions, among them discovering four of the satellites of Jupiter and improving the telescope. But for defying convention, for favoring science over Scripture, he was persecuted and made to suffer, isolated from society in his advanced years when he was debilitated and blind.

That Galileo did not see justice served upon him in his own lifetime is historically moot. A papal apology for the Holy Office’s condemnation of the scientist was offered in 1992. Although official vindication for the brilliant Renaissance physicist did not come until three centuries after his death, he didn’t have to wait so long for payback.

It is crudely apropos that nearly a century after his death, when his writings were gaining credence and stirring the imaginations of other bright successors, he had plucked from him a particular anatomical vestige. For his allegedly radical ideas and discoveries, Galileo’s contemporaries gave him a hard time. In return, the esteemed and exonerated scientist gave history his middle finger.

LOCATION: Institute and Museum of the History of Science, Florence, Italy.