DATE: 1744-1748.

WHAT THEY ARE: Three bound journals containing learning exercises written by George Washington when he was between the ages of twelve and sixteen.

WHAT THEY LOOK LIKE: The cover of the “School Copybook” is dark blue with gold tooling and measures 15⅛ inches long by 10⁵/₈ inches wide; its folios measure 14⁷/₈ inches long by 10 inches wide. The cover of George Washington’s “Second School Copy Book” is red and measures 12⅛ inches long by 9 inches wide; its folios measure 11⁹/₁₆ inches long by 7⁵/₁₆ inches wide. The front cover of the “Forms of Writing” copybook is black with gold tooling and measures 10³/₁₆ inches wide by 14¹³/₁₆ inches long; its folios measure 8³/₁₆ inches wide by 12½ inches long. The pages of the “School Copybook” and “Forms of Writing” copybook are inlaid (set inside cutout pages that are overlaid by sheer silk glued on both sides); those of the “Second School Copy Book” are hinged (attached with a folded piece of paper to a support sheet). Much of the print in the journals appears faded, and some of the words are no longer visible on the leaves.

He trekked through the wilderness, braved the harsh elements, met nature head-on in carrying out missions of vital importance to his fledgling nation in the New World, the mostly uncharted land on which English settlers had first set foot little more than a century earlier. But before he thrashed through the frontier, trained soldiers in the art of warfare, led militias over mountains and across rivers, engaged in fierce battles, and took the reins of a newly independent nation—indeed, long before, as he was developing his emotional and intellectual character while a raw lad—George Washington set himself to becoming a colonial gentleman and wrote out exercises that addressed such vexing social issues as these:

Is it proper to clean one’s teeth with a tablecloth? Speak out loud while yawning? Drum one’s fingers in the presence of others? Rinse one’s mouth in company? Point one’s finger when talking? Use reproachful language? Touch any part of one’s body that is not usually observed?

Welcome to George Washington’s “Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior In Company and Conversation,” a fascinating, if sometimes amusing (at least by our modern frame of reference) guide to good manners, etiquette, and moral behavior. Occupying the last several pages in Washington’s “Forms of Writing” copybook, “The Rules of Civility” were derived from ethical precepts formulated by sixteenth-century French Jesuits. The influence of the rules on young George is apparent in the character of his later life.

There are three surviving compilations of what are referred to as George Washington’s schoolboy copybooks. Many writings of the first U.S. president exist, such as letters, notes, instructions, and ledgers, but the schoolboy copybooks are special for various reasons: little is known about George Washington’s early years, so they shed light on his youth; they open a window on colonial education and social etiquette; and they show young Washington to be meticulous and hard-driven, traits evident in the man who led the American Army to victory over the British Redcoats in the Revolutionary War, presided over the Constitutional Convention, and was unanimously voted by electors to be the first president of the United States of America. In his adult years Washington was conscientious in his personal life and professional career, and consequently he was a prolific writer of letters, messages, accountings, and other items. He wrote lucidly and eloquently, and his schoolboy copybooks evince the man who would become such a fastidious, careful, and dignified individual.

Like his “Forms of Writing,” George Washington’s “School Copybook” and “Second School Copy Book” contain a potpourri of writings, but these latter volumes concentrate more on learning exercises, particularly in the areas of mathematics and geography. The “School Copybook,” dated 1745, contains numerous exercises with titles such as “Geometrical Definitions,” “Geometrical Theorems,” “Surveying,” “Solid Measure,” “Gauging,” and “Geographical Definitions.” On one page of this volume young George wrote out the definitions of such geometric concepts as straight and obtuse angles, as well as drawing a variety of geometrical shapes to illustrate the definitions. On other pages he worked out geometrical problems such as “How to measure a piece of land on the form of a circle.”

There are pages headed “Memorial Verses” that are divided into several boxes with definitions and mathematical exercises related to the calendar. Mathematical exercises in the “Memorial Verses” pages include “What is the golden number for the present year 1746,” “What was the cycle of the sun for the year 1707,” and “What will be Easter Day Anno 1749.” On other pages of the “School Copybook,” Washington wrote out definitions of geographical terms such as island, peninsula, isthmus, promontory, sea, strait, creek, and bay, named the bodies of water surrounding Africa and America, and listed the provinces of North and South America.

Much of Washington’s “Second School Copy Book” is devoted to mathematical exercises. For instance, the first entry is entitled “Multiplication of Feet, Inches & Parts.” Other entries include “Notation of Decimals,” “Addition of Decimals,” “Subtraction of Decimals,” “Multiplication of Decimals,” “Division of Decimals,” “Reduction of Decimals,” “Concerning Simple Interest,” “Plain Trigonometry Geometrical and Logarithmetical,” “Plain Trigonometry Oblique,” and “Surveying of Land.”

Here are examples of actual entries:

Notation of Decimals: Example: This decimal fraction 25/100 may be written thus .25; its denominator being known to be a unit with two cyphers [zeroes] because there are two figures in it. Numerator in … like manner 125/1000 may thus be written .125; and 3575/10000 thus .3575 and 75/1000 thus .075 and 65/10000 thus .0065.

Another entry reads:

Concerning Simple Interest: 1st. When money pertaining or belonging to the person is in the hands, possession or keeping, or is lent to another, & the debtor payeth or alloweth to the creditor, a certain sum in consideration for forbearance for certain time; such consideration for forbearance is called interest, loan, or use money; & the money so lent, & forborne … is called the principal. 2. Interest is either simple or compound. 3. When for a sum of money lent there is a loan or interest allowed. And the same is not paid, when it becomes due; & if such interest doth not then become a part of the principal it is called simple interest.

There are also many mathematical computations the young Washington carried out, such as 3.1252 x 2.75, or the interest on a sum of money for one year at 6 pounds.

The entries in the “Forms of Writing” copybook begin with a promissory note dated March 12, 1744/45, and a Bill of Exchange dated May 27, 1745, and end with “The Rules of Civility.” In between are entries with titles such as “An Arbitration Bond,” “Form of a Servants Indenture,” “A Bill of Sale,” “Deed or Conveyance for land by a man and his wife,” “Lease of Land,” “Form of a Virginia Patent for land,” “Form of a Virginia warrant,” “To Keep Ink from Freezing or Moulding,” and “Christmas Day” (a poem).

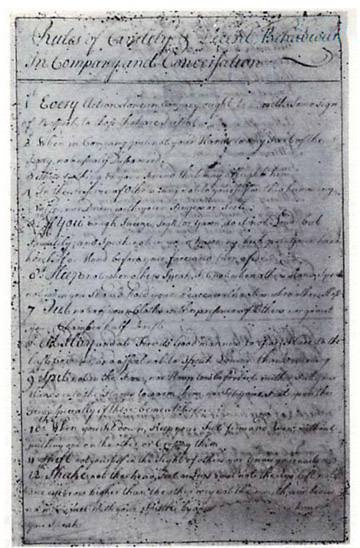

“The Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior In Company and Conversation,” the best-known entry in Washington’s school copybooks, consists of 110 numbered maxims written on ten pages. The handwriting is in the old style, in which the letter s looks like an f, so that the word presence seems to be spelled prefence, and discourse, difcourfe. Not all the rules concern manners; many concern religious and moral behavior. Here are some of the rules Washington wrote out (with their designated numbers):

2. When in company put not your hands to any part of the body not usually discovered.

4. In the presence of others sing not to yourself with a humming, noise, nor drum with your fingers or feet.

5. If you cough, sneeze, sigh, or yawn, do it not loud but privately, and speak not in your yawning, but put your handkerchief or hand before your face and turn aside.

7. Put not off your cloths in the presence of others, nor go out your chamber half dressed.

58. Let your conversation be without malice or envy, for ’tis a sign of a tractable and commendable nature.

76. While you are talking, point not with your finger at him of whom you discourse nor approach too near him to whom you talk especially to his face.

100. Cleanse not your teeth with the table cloth, napkin, fork, or knife but if others do it let it be done with a pick tooth.

101. Rinse not your mouth in the presence of others.

108. Honour and obey your natural parents altho they may be poor.

110. Labour to keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience.

“The Rules of Civility” contain some precepts that might now seem outdated, but many of the rules hold up well. People of any age can take a lesson from “In visiting the sick, do not presently play the physician if you be not knowing,” and can surely apply the admonition not to dispense advice if one is not an authority on a particular subject. Indeed, as archaic as the language in which the rules are couched may sound, their content makes the point that good manners never become outdated.

The first page of the "Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior In Company and Conversation" in Washington's hand. The printing is faded but still legible.

In his copybooks, George Washington’s script is neat and flowing, almost calligraphic; his drawings of geometrical shapes are precise and artistic. Although his education was limited, Washington’s penmanship and drawings show a student who took care and pride in his work.

The original order of the pages is not known; in the mid-nineteenth century, the U.S. government purchased the exercise pages from a Washington family descendant, and sorted and bound the leaves into copybooks.

Little is known about George Washington’s education. He once indicated that he had been principally instructed by a private tutor. On the other hand, he may have had some institutional schooling in the last years of his education, as fellow Virginian George Mason, in a mid-1750s letter to Washington, noted that he had run into an “old schoolfellow” of Washington. In any case, whether by private tutor or in school, Washington’s academic education ended when he was about sixteen years old.

While the original documents from which “The Rules of Civility” were derived may have been intended for use in the schooling of aristocratic children, George Washington’s education in itself was weak by standards of the day for children from families of means. With the inheritances he received at a young age, however, George Washington had financial subsistence, at least in terms of property.

Washington’s father, Augustine, had four children by his first wife and six by his second. George was the first offspring of his father’s second marriage, to Mary Ball in 1731. Augustine Washington died in 1743, but George, who was eleven at the time, was close to some of his half-siblings, including Lawrence, with whom he traveled to the West Indies and whose Mount Vernon estate eventually passed to George. But it was while living with Lawrence, who became his guardian after his father died, that young George was introduced to the profession of surveying. Lord Fairfax, the cousin of Lawrence’s wife, had massive landholdings in Virginia and dispatched parties to survey his land so squatters could pay taxes. As a teenager, George would sometimes accompany these expeditions, receiving land as compensation for his services. By the time he was seventeen, he was appointed a county surveyor, learning much as he journeyed into the wilderness of the westward land. His youthful experience in the wilderness no doubt aided him later when he commanded the Continental Army and, along with his men, endured great hardships in fighting the British, from fiercely cold winters to meager supplies of food.

A nineteenth-century illustration of George Washington playing as a youth. While young Washington was becoming acquainted with the vast wilderness, he was also studying to become a proper colonial gentleman.

Washington’s lack of formal education by no means impeded him from gaining an elevated station in life, which he achieved via his self-confidence, physical strength, natural intelligence, curiosity, and ability to absorb information from people, nature, and the totality of his outside world. While contemporaries like Thomas Jefferson, who became the third U.S. president, and John Adams, Washington’s vice president and presidential successor, were known as great intellects, Washington’s self-determination, resoluteness, and practical abilities no doubt not only allowed him to excel at whatever endeavors he undertook, but enabled him to lead a fledgling nation to heights greater than those to which it might have risen under a genuine scholar. He did make grave military blunders on occasion, and there were bleak times when his armies came close to falling apart, but his strong nature kept his soldiers together.

Washington heeded well his early lessons on etiquette, because he did indeed grow into a proper colonial gentleman. He was courteous and possessed of great integrity, although he may have been a little too straitlaced. Charles Biddle, the acting chief executive of Pennsylvania, said of him, “He was a most elegant figure of a man, with so much dignity of manners that no person whatever could take any improper liberties with him.”

As a soldier during the Revolutionary War, Washington was naturally itinerant and was known to have accepted hospitality in many a dwelling in the northeast United States; the familiar phrase “George Washington slept here” derives from his nomadic military life. And through it all Washington maintained his propriety. One might even hazard a guess that in his frequent intercourse with colonial folk, the hero of the emerging nation never took out his false teeth at the dinner table to clean them with the tablecloth, never spoke while he yawned or rinsed his mouth in the company of others, and never put his hands to a part of his body not usually observed. Washington seemed to carry for life the honorable precepts he set down in the 1740s in his schoolboy copybooks.

LOCATION: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.