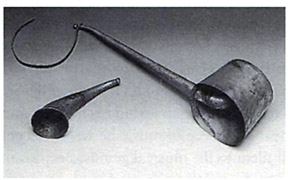

DATE: circa 1812-1813.

WHAT THEY ARE: Two pairs of “listening tubes” that were designed to improve the composer’s hearing.

WHAT THEY LOOK LIKE: The hearing aids consist of long tubes connected to funnels and are made of brass.

Of all the musical sounds ever produced by humans, from the first babbled melody to the latest chart-topper’s catchy chorus, the most famous, enduring, and universally recognizable motif is arguably the simple but arresting sequence of notes that opens Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Indeed, the sublime genius of Beethoven, with his oeuvre of nine symphonies, thirty-two piano sonatas, and numerous orchestral, chamber, choral, and other works, has been recognized for two centuries both by common folk and by celebrated musicians alike. But fate dealt a cruel hand to the prodigious composer when he was a young man by robbing him of a vital sense. Before 1800, when he was not yet thirty, the maestro began losing his hearing and eventually became deaf, unable to hear any piece of music he wrote except in his mind. As the outside world fell silent to the musical genius, Beethoven withdrew from society and plunged into his work, immersed in his own private torment.

When Beethoven realized his ability to hear was fading—noticing that he had to draw his head closer to the piano to hear when he played—he tried everything he could think of to ameliorate his condition, from visiting physicians to applying salves and other remedies, all to no avail. The composer despaired at his lack of success and was embarrassed by his condition, letting few of his friends know at first. Despite his growing deafness, he still carried on his life as best he could. “To give you an idea of this curious condition,” he wrote to a friend, “I must tell you that in the theater I must get close to the stage in order to hear the actors. If I am at a slight distance then the high notes of instruments and singers I do not hear at all. I can often hear the low tones of a conversation but I cannot make out the words. It is strange that in conversation people do not notice my lack of hearing but they seem to attribute my behavior to my absence of mind. When people speak softly I hear tones but not the words. I cannot bear to be yelled at. Heaven knows what will come of this.”

But as the sounds of life faded over the years, Beethoven (who was born in Bonn, Germany, in 1770 but spent most of his professional life in Vienna) even contemplated suicide. He agonized over his hearing loss and became more impatient and short-tempered with those around him. “For me there can be no recreation in the society of my fellows, refined intercourse, mutual exchange of thought,” the composer wrote in 1802. “Only just as little as the greatest needs command may I mix with society. I must live like an exile.”

It is not known whether it was at the composer’s behest or the maker’s initiative, but around 1812 or 1813, Johann Nepomuk Mälzel made four brass “Horinstrumente,” or listening instruments, for the maestro. Beethoven was acquainted with Mälzel (1772-1838), having composed his op. 91, “Wellington’s Victory,” for Mälzel’s mechanical musical instrument, the Panharmonikon, in 1813; in later years Beethoven used a metronome developed by Mälzel for tempo markings.

Beethoven hoped that Johann Nepomuk Mälzel's ear trumpets, pictured above, might enable him to better hear the music he composed. But the primitive hearing aids did not help Beethoven and the composer's hearing loss continued to grow worse over time.

Mälzel intended that as sounds passed from the funnel through the tubes of his ear trumpet, their volume would increase, and when they made direct contact with the listener’s ear on the other end, the person would be able to hear them more clearly. Unfortunately, Mälzel’s ear trumpets didn’t help Beethoven much, if at all, and the composer’s hearing continued to worsen. By 1818 Beethoven was totally deaf and could not communicate orally. Visitors to his home used “conversation books” to write their communications to him. When he could no longer hear, Beethoven relied on his auditory memory to compose. The composer, whom Mozart praised and Vienna’s nobility embraced admiringly, was condemned to an existence of external silence.

Poor Beethoven! His music was timeless, but the technology of his day was too primitive to remedy his physical impairment. But his condition gives rise to an intriguing question: If Beethoven had lived at a later time, say the late twentieth century, would technology have been able to help him hear, or even to cure his deafness?

Whether Beethoven’s condition could have been improved or cured would have depended on the etiology of his deafness, which is uncertain. However, from a description of his condition written to his friend Karl Amende, it appears that he had a progressive sensorineural hearing loss (a hearing loss derived from a problem in the inner ear). Initially, Beethoven experienced a “whistle and buzz continually” in his ears. This tinnitus may have been due to the degeneration of hair cells in the cochlea. High-frequency sounds were lost first, and then the low tones.

Modern technology probably could have improved Beethoven’s condition. Once his deafness was diagnosed, he would have been fitted with hearing aids. These would have made sounds louder, so he would not have needed to get so close to his piano keys to hear. He could also have utilized an FM system in the concert auditorium so that sounds from the orchestra would be delivered into his hearing aid directly, like a personal radio station. This system would have also eliminated the distracting background mumble of the audience. With special frequency-transposing hearing aids, his speech discrimination would have been improved, so in conversations he would have been able not only to detect voices but also to discriminate some spoken words as well.

With modern developments in assistive technology, he might have been a candidate for a cochlear implant when his hearing loss became profound. With his excellent auditory memory, the implant would have allowed him to hear with an internal coil inserted into his cochlea to substitute for the missing hair cells. This coil would receive sound information from an external ear-level microphone and speech processor that Beethoven would have worn at his waist or behind his ear.

In this nineteenth-century painting by A. Grafle, Beethoven plays for a small but appreciative audience.

The speech processor, a tiny computer, would have had several programs to choose from. The composer could have selected the best one depending on the environment he was in. One setting would allow him to hear better in conversation, one at a noisy gathering, and another when listening to music. He would have needed to relearn sounds, however, because the new signals he received would have sounded different from what he had heard in the past. Once his brain had made the switch, he probably would not have lapsed into the despair he felt at the end of his life.

One can only dream of what music the highly original Beethoven, who diverged from Mozart’s and Haydn’s pure classical form and initiated the Romantic period, might have composed had he had access to modern hearing-device technology. Then again, it could have been his deafness that drove him to create the masterpieces he did once he became isolated in the sanctum of his own inner voices.

Beethoven didn’t even complete his famous Symphony no. 5 in C Minor with its stirring opening theme until around 1808, when his hearing loss was marked and he was well acquainted with despondency.* Had they worked, the ear trumpets Mälzel made for Beethoven could have spared one of history’s greatest musical geniuses the physical and emotional torment that ravaged his life; perhaps they could have enabled him to give to the world an even more glorious body of music. But besides the immortal music he did compose, among the items Beethoven left to posterity are two sets of ear trumpets, which, in their futility, demonstrate that despite a debilitating physical handicap, Beethoven’s genius and determination prevailed, enabling the great maestro to enrich the ages.

LOCATION: Beethoven House, Bonn, Germany.*

*The first four notes of Symphony no. 5 were used during World War II as the station identification signal by the BBC European Service and as an Allied signal meaning “Victory”; in Morse code, the sequence of three shorts and a long stands for V.

*Beethoven’s hearing aids came into the possession of his clerk, Anton Schindler, probably as an inheritance from the composer. Schindler donated the hearing aids to the Königliche Bibliothek in Berlin, which in 1889 presented them to the Beethoven House on the recommendation of the king of Prussia.