DATE: 1846.

WHAT IT IS: A sword used in a famous duel of the Mexican War.

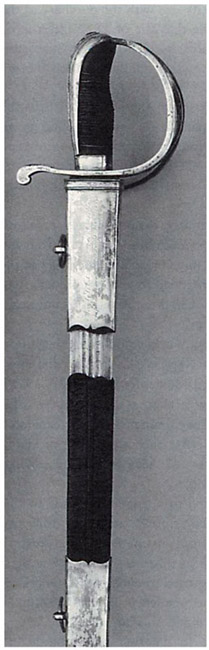

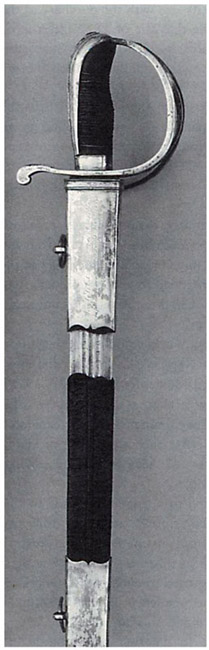

WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE: The sword measures 4½ inches; all its mountings, including the hilt and sheath fittings, are made of sterling silver. There are inscriptions on either side of the sheath’s upper ring, one side reading “Worn by Lt. Col. Nagera [sic], of the Mexican Lancers who fell in personal combat with Col. John C. Hays of the Texas Rangers,” the other side reading “Captured in the battle of Monterey/Septem.r 21st 1846.” The blade contains an engraving in Spanish (whose view is partly obstructed by the scabbard), which, roughly translated, reads, “Draw me not with anger, sheath me not without honor.”

Adventure-movie aficionados everywhere would immediately recognize this tense one-on-one battle scene: amid a throng of excited onlookers, an American swashbuckler faces off against an intimidating foreigner wielding a sharp saber. With his nemesis preparing to deliver a fatal blow, the American, empty-handed and apparently defenseless, simply reaches for his holstered pistol and pumps one fatal round into his challenger, felling him instantly.

The confrontation between Indiana Jones and the black-robed thug in Raiders of the Lost Ark? Well, let’s just say that history in all its sundry dramas has an uncanny way of anticipating fictionalized entertainment. Try the mid-nineteenth-century duel between the cool and intrepid Texas Ranger Jack Hays and a bold and little-known Mexican Army colonel!

It was the Mexican War that provided the setting for this real-life derring-do on an open range in Mexico in 1846. The war had its roots in the expansionist fever that began to sweep America around the turn of the nineteenth century. In 1803 the United States doubled its size with the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France, and while the War of 1812 interrupted U.S. plans to absorb northeastern Florida after its agents stirred Americans there into rebellion against the Spanish, America finally acquired Florida from Spain in 1819 with the Adams-Onis Treaty.

In the 1840s, the concept of Manifest Destiny—the idea that it was the natural course for the United States to expand its westward boundary all the way to the Pacific Ocean, so that the country’s borders would extend “from sea to shining sea”—emerged in full bloom. There were many provinces to the west that could be added to the United States, and Texas seemed a good first acquisition.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, major changes were also taking place in Mexico. Since Christopher Columbus had opened up the New World for Europe in 1492, Spain had mined its colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere, and Mexico had been added to that empire less than thirty years later, when Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztecs through campaigns that sometimes employed cruel tactics.

Najera's battle sword. Engraved on the upper section of the sheath on one side is the legend: "Worn by Lt. Col. Nagera, of the Mexican Lancers who fell in personal combat with Col. John C. Hays of the Texas Rangers."

Spain’s grasp on Mexico and its other New World colonies had been firm for almost three hundred years, until the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s weakened Spain, and France invaded Mexico (around 1808). With Spain’s power now eroded, Mexicans saw a chance to gain their independence and in 1810 began a revolution that culminated eleven years later, in 1821, with independence from Spain. Texas, once a province of Spain, became absorbed into the new Republic of Mexico, which invited Americans to settle in its new northern territory.

Indeed, efforts had already been mounted to attract Americans to this vast area when Moses Austin, in 1820, tried to create an Anglo-American colony there by obtaining a land grant from Spain. Following Austin’s death in 1821, his son, Stephen, continued his mission to bring in settlers, an effort so successful that in 1830 Mexico tried to curb further immigration. But the settlers desired their own independence—not to mention a continuation of slavery, which Mexico wanted to end—and the Texans eventually rebelled against the Mexicans. In the first major battle, on October 2, 1835, the Americans defeated Mexican soldiers at the Guadalupe River; but the next year, after Texas had declared its independence, the Mexican Army defeated the Texans at the Alamo in San Antonio.

With the Alamo massacre burning in their minds, the Texans retaliated at San Jacinto and drove the Mexican Army out of their territory. The Texans formed the Lone Star Republic, an independent political entity that became a focal point of interest for many countries. European powers wanted it to remain independent to prevent America from expanding. For the United States, the Texas Republic was controversial; southern and western states favored its annexation, while northern states resisted, not wanting to add another slave state. In early 1845, however, after an unsuccessful attempt in the Senate to establish a treaty providing for Texas’s annexation, Texas was finally admitted to the Union when Congress passed a joint resolution.

Mexico’s outrage at this action was further exacerbated by the United States’ claim that the Rio Grande was the international border between the United States and Mexico (Mexico contended the Texan border was the Nueces River) and by American intentions to claim more northern Mexican lands. After John Slidell, who had been dispatched to Mexico by President James Polk in November 1845 to try to purchase New Mexico and California and settle the border dispute, failed in his mission, Polk sent soldiers to the area of the border dispute.

On April 25, 1846, a battle erupted between forces of the two countries when a Mexican regiment crossed the Rio Grande to engage a waiting American cavalry led by General Zachary Taylor. President Polk asked Congress to declare war, arguing that Mexico had “shed American blood on American soil.” Within a few weeks Congress authorized the president to recruit volunteers into the army and granted $10 million for the United States to attack Mexico. The southern states embraced the war, while the northern states opposed it on the grounds that Mexico, which had become an independent country only twenty-five years previously, was a weak country, and that annexing Texas would inflame the slavery issue.

Meanwhile, on May 8, 1846, another battle erupted at Palo Alto, Texas, in which Zachary Taylor led the Americans to their first major victory in the then-undeclared war. War officially came shortly after, however; the United States made its declaration on May 13, and Mexico reciprocated against its northern neighbor ten days later. Thus the Mexican War was official, with many new battles to be fought and much more blood to be spilled.

In the early morning hours of September 21, 1846, Zachary Taylor received a note from General W. J. Worth recommending that the enemy be diverted at the eastern end of Monterrey. Taylor concurred. While it was still dark, Colonel John Coffee Hays, a Texas Ranger who had received a commission in the army, led a scouting party to determine if the enemy was preparing to ambush Worth’s camp. Through the night it had been raining, and Hays’s rangers had had to sleep on the wet ground without blankets to protect them from the cold air. After riding about a mile, Hays stopped his unit, deciding to wait until dawn broke; his men dismounted and made camp, some falling immediately to sleep.

When sunlight broke through the darkness, it revealed a stunning sight—a Mexican cavalry brandishing lances with flapping pennons six hundred feet away. The Mexican cavalry’s leader ordered his men into formation. Colonel Hays issued an order for his rangers to prepare themselves for battle, then mounted his horse and headed out to meet the enemy.

After riding a couple of hundred feet, Hays, an experienced Indian fighter, confronted the Mexican leader, also on horseback. Hays bowed. The Mexican colonel, whose name was Juan N. Najera, returned the gesture by removing his headgear. Hays, wearing a bandanna and holding a saber, challenged his counterpart to a duel, and Najera accepted. Hays’s men, now awake and watching, wondered about their leader’s intentions, since he was not known to be an adept swordsman.

In moments the duel was ready to commence. The Jalisco cavalry (part of General Manuel Romero’s brigade) and the Texas Rangers, situated on opposite sides, fixed on the two combatants. As Hays slowly advanced, without warning the Mexican colonel suddenly charged, swinging his sword. Hays swerved, losing his grip on his own sword, which fell to the ground. But Najera had turned and was bearing down on his now-unarmed adversary. Before his nemesis could cut him down, Hays drew one of his pair of six-shooters and fired a shot into Najera, dropping him from his horse and killing him instantly.

Hays bolted toward his men, who were now on their horses, and shouted for them to get off and take cover behind their mounts. The Mexican cavalry charged, but the rangers held them off, killing dozens but losing only one of their own men. The Americans knew their death toll would have been much higher save for the order by Hays to dismount and take cover.

The Americans continued to defeat the Mexicans in battle after battle until even the American pioneers in California forced Mexican officers out. In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided for settlement of the war, with Mexico to cede California and New Mexico to the United States and recognize the Rio Grande as Texas’s southern border, in return for a U.S. payment of $15 million to Mexico.

When the Mexican War finally ended in 1848, John Coffee Hays decided to pursue a career outside the military. But he was to be no ordinary civilian. The reputation of the Texas Rangers from the Mexican War had spread far and wide, with Hays perhaps the most famous of this stalwart bunch.

Hays’s fame is a typical example of the larger-than-life esteem in which mid-nineteenth-century easterners held their western heroes. In 1853, for example, Hays wanted to attend the presidential inauguration of his old friend and fellow Mexican War officer, Franklin Pierce, in a bid to be appointed California’s surveyor general. Before arriving in the nation’s capital he stopped off in New York, where one day he was recognized by a man talking in the street with an acquaintance. The man remarked to his friend, “That’s Colonel Jack Hays, the famous Texas Ranger,” whereupon his friend shouted, “My God, hurry up and catch him. I’d rather be introduced to him than any man in the world.”

The man accosted Hays and introduced his friend. The man later wrote, “After the interview I had hard work convincing my friend that the modest, unpretentious, mild, quiet-toned gentleman he talked with was the world-renowned Jack Hays, the Texas Ranger. He had expected to see a man breathing fire and with the war over look conspicuous and overpowering in every feature.”

Hays’s presence at Pierce’s inauguration and at the celebration that followed drew the attention of the public and the newspapers. One reporter wrote that of all the people in the capital for the inauguration, the center of interest was the Texas Ranger, Jack Hays, about whom “it may be safely asserted that no man in America … since the great John Smith explored the primeval forests of Virginia … has run a career of such boldness, daring and adventure. His frontier defence of the Texas Republic constitutes one of the most remarkable pages in the history of the American character.” Needless to say, Hays was awarded the federal surveyor-general post that he had come to Washington to seek.

While he was a ranger, Hays had befriended a Comanche chief named Buffalo Hump, and one day he had idly promised to name his first son after the Native American. When his first son was born in California, Hays made good on his promise. Hays’s uncle sent word to Buffalo Hump that his old friend from Texas had a son, and that Hays had given his son the chief’s name for a nickname. Buffalo Hump promptly purchased two gold-washed silver spoons (one is engraved “Buffalo Hump Hays,” the other “BHH”) and a matching cup, and had a friend deliver these items to the Hays family in San Francisco.

After the duel in which Hays shot and killed Najera, either Hays recovered the Mexican colonel’s sword from the battlefield as a souvenir or one of his men retrieved it to present to him as a gift. It stayed in Hays’s family until about 1989, when John Hays, a direct descendant and namesake of the celebrated “Captain Jack,” and his mother donated the sword along with other original John Hays artifacts, including the Buffalo Hump Hays silver spoons, to its present home. Today the sword serves as a symbol not only of gallant duels fought with pride and courage in the interests of national ambition, but of a historic struggle in which Texans fought hard for their independence.

LOCATION: Autry Museum of Western Heritage, Los Angeles, California.