DATE: 1885.

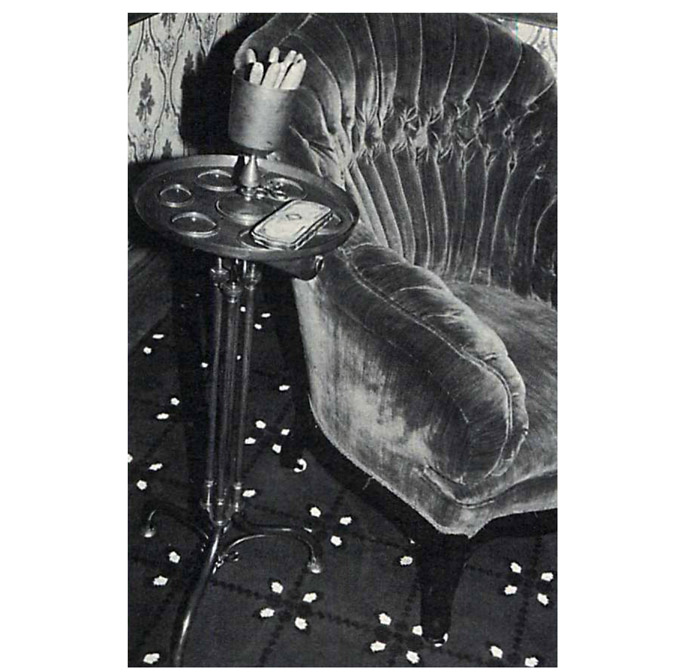

WHAT IT IS: A decorative piece of furniture designed to hold cigars that belonged to the Civil War general and eighteenth president of the United States

WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE: The stand has a three-pronged footed pedestal and a rounded top with indentations on which to put cigars; it is 38¾ inches high. It is made of brass, and in the center at the top is a removable goblet used to hold cigars that bears the initials “USG” on one side and an etching of a horse in mid-leap on the other. The goblet sits on a tray that is 13 inches in diameter; under the tray is a drawer in which reading glasses could be placed.

As its shrewd military leader, Ulysses S. Grant was instrumental in guiding the Union to victory in the American Civil War. He planned and led daring campaigns and forced Confederate strongholds to surrender, surviving it all with such heroic aplomb that he was elected by popular vote to lead the nation he helped reunify. Yet his most perilous battle was against the army of stogies he encountered almost daily during his military and political leadership, a continuing engagement in which the toxins in the dark tobacco cylinders ravaged his body and inflicted torturous pain upon him until he eventually succumbed.

Perhaps it was a combination of the Victorian times he lived in and his own fame that launched the American soldier onto this path of self-destruction, because prior to the 1862 battle at Fort Donelson on the Cumberland in western Tennessee, Ulysses S. Grant was merely an occasional pipe smoker. But with his victory over the Confederates at Fort Donelson—in which he responded to Brigadier General Simon B. Buckner’s proposal for an armistice by making his celebrated written stipulation, “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted”—his admirers honored him, as was customary, with gifts, in his case cigars and related paraphernalia, as a token of their appreciation. Grant would often take the time to thank his admirers, as he did in this letter of June 5, 1863, to Mrs. Mary Duncan of New York City: “My Dear Madam I have just received your beautiful present of a Cigar Case and will continue to carry and, appreciate it, long after I could have done ‘smoked’ any number of cigars the Express company are capable of transmitting. …”

Indeed, by the time of the Battle of the Wilderness in Virginia in May 1864, in which Grant was attacked hard by Confederate forces but valiantly held his ground, the general was a heavy smoker—thanks in no small part to those who continued to ply him with cigars. In early October 1864, Grant thanked U.S. Representative John Bidwell in a letter: “I have the pleasure of acknowledging the receipt of two boxes of very superior segars sent by you. Please accept my thanks for this mark of your esteem and recollection of your visit to this Army.”

The tobacco continued to roll his way until the general had become thoroughly addicted. Here’s Grant himself in 1865, recalling how he had developed a fondness for cheroots:

I had been a very light smoker previous to the attack on Fort Donelson, and after that battle I acquired a fondness for cigars by reason of a purely accidental circumstance. Admiral Foote, commanding the fleet of gunboats which were cooperating with the army, had been wounded, and at his request I had gone aboard his flag-ship to confer with him. The admiral offered me a cigar, which I smoked on my way back to headquarters. On the road I was met by a staff-officer, who announced that the enemy were making a vigorous attack. I galloped forward at once, and while riding among the troops giving the directions for repulsing the assault I carried the cigar in my hand. It had done out, but it seems that I continued to hold the stump between my fingers throughout the battle. In the accounts published in the papers I was represented as smoking a cigar in the midst of the conflict; and many persons, thinking, no doubt, that tobacco was my chief solace, sent me boxes of the choicest brands from everywhere in the North. As many as ten thousand were soon received, I gave away all I could get rid of, but having such a quantity on hand, I naturally smoked more than I would have done under ordinary circumstances, and I have continued the habit ever since.

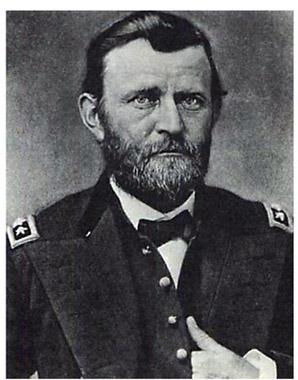

Despite warnings that cigars could adversely affect his health, Ulysses S. Grant, pictured above, was an inveterate cigar smoker.

Horace Porter, an aide to Grant who chronicled some of the general’s later military campaigns, reported that after breakfast Grant’s servant would bring the general two dozen cigars, one of which he would smoke immediately; the others he would stuff in his pockets to give out to others or puff on later in the day, whether in the heat of battle or while relaxing. Porter noted that “a lighted cigar was in his mouth almost constantly.” Indeed, Grant smoked from morning to night. As Porter described one memorable day, “Deducting the number he had given away from the supply he had started out with in the morning showed that he had smoked that day about twenty, all very strong and of formidable size. But it must be remembered that it was a particularly long day. He never afterward equaled that record in the use of tobacco.”

In January 1865 Porter wrote, “When the chief had lighted his cigar after the morning meal, and taken his place by the camp-fire, a staff-officer said: ‘General, I never saw cigars consumed quite so rapidly as those you smoked last night when you were writing despatches to head off the ironclads.’ He smiled, and remarked: ‘No; when I come to think of it, those cigars didn’t last very long, did they?’”

When the Civil War ended in 1865, Grant was a war hero, and he would soon find that his admirers’ desire to honor him was insatiable. Private citizens, soldiers, businesspersons, politicians, and others relentlessly imparted to him all types of gifts, and there seemed to be no limit to the expense to which they would go. In August 1865, Grant was given a hero’s welcome in a gala celebration that included a parade and fireworks when he returned to Galena, Illinois, where his family had settled five years earlier, and some citizens of the town bequeathed him a two-story furnished brick house, not the first such gift, which he would only occasionally visit.

After the war Grant determined to moderate his cigar habit. In a newspaper interview that took place in May 1866, during a sitting for noted Maine sculptor Franklin Simmons, Grant said, “I am breaking off from smoking. When I was in the field I smoked eighteen or twenty cigars a day, but now I smoke only nine or ten.”

But aware of his fondness for stogies, soldiers were adamant in lavishing upon Grant, now General of the U.S. Army (the first to hold that rank), a veritable torrent of cigars. Shortly after the USS Susquehanna anchored in Havana harbor in mid-November 1866, Lieutenant General William Tecumseh Sherman, famous for leading the “March to the Sea” in which his soldiers destroyed rail lines and supplies from Atlanta to the Atlantic Ocean, remarked in a letter to Grant, “I will be sure to lay in for you five thousand cigars of good quality trusting to bring them to you in due season.” Sherman made good on his word, writing Grant just three weeks later from Brazos Santiago, Texas: “When at Havannah I bought you five thousand segars, three thousand at $57, and two thousand at $34.” These notes about the cigars were embedded in detailed reports Sherman made about his military mission to Mexico. Grant himself was not too preoccupied to acknowledge Sherman’s kind interest, as Bvt. Brigadier General Cyrus B. Comstock shortly wrote to Sherman, “General Grant requests me to enclose the within check for the cigars, for $210 in coin. The cigars have arrived but I don’t believe the general who has been under the weather has opened them yet. He sends his thanks.”

Grant continued diligently to thank those who bestowed cigars and related paraphernalia on him. Here’s Grant in a letter of January 21, 1867, to Miss Mary Jane Safford:

I owe you an apology for not earlyer acknowedeing the beautiful token of remembrance which you were so kind as to send me about one month ago. The box containing it came duly to hand and supposing it to be a box of cigars, a present which I often get, it was sent to the house where I have several dozen boxes just like it, though with different contents. I supposed that a letter would come along through the Mail announcing who had favored me, as is usually the case. But no letter came and the matter was forgotten until last evening I had occasion to open a fresh box of cigars, and accidentally opened the one you sent me, and there found your letter and beautiful present. It was the first I knew of your return from Europe. I was indeed glad to hear from you and shall also prize most highly both your letter and the cigar holder which I shall preserve in remembrance of the donor.

Even in Grant’s time, the dangers of tobacco were suspected, and some didn’t hold back in letting the general know it. In an open letter to Grant that appeared in the Chicago Times in April 1867, George Trask, a Massachusetts gentleman who railed against the health risks of smoking, took him to task for his habit and the example he set:

Public men we regard as public property; hence their public acts are legitimate subjects of public animadversion. Newspaper reporters … identify you with your cigar, and find pleasure in proclaiming … that you are a great smoker as well as a great general. Whether they report you in one battle or another, in the siege of Richmond or the capitulation of Lee, receiving the homage of fair women or the noisy applause of men, they “ring the changes” on “Grant and the inevitable cigar.” You conquered, general, in spite of your cigar. … We address you, general, with sincere respect and gratitude; still … we make no apologies for assaulting a vice which you persistently obtrude upon public notice. The war we wage is simply defensive. Your habit is contagious, and, associated with your powerful name, is doing irreparable mischief in the great community. … Dear general, we ask you to set a better example to our military and naval schools, to our army and nation. You have conquered a city; the world calls it a great achievement. We ask you to conquer a despotic habit … and God’s Word will justify us in calling it a great achievement.

Evidently, this warning, and others that he undoubtedly received, did not deter Grant. In May 1868, Grant wrote to H. Bernd of Danbury, Connecticut, “Please forward to my address, pr. Adams Ex. One Thousand ‘Colfax’ segars to collect on delivery.”

Grant was elected president in 1868, and when he took office the following year for the first of two terms, he continued his cigar smoking in the Executive Mansion (later officially called the White House), spending considerable amounts on orders for new cigars. In the early 1870s, for example, he sent checks to John Wagner, a Philadelphia cigar dealer, in the amounts of $118, $182, and $240, not insubstantial sums at the time, and on several occasions ordered a thousand or two thousand cigars at a time. The fact that he was president did not deter people from continuing to bestow stogies upon Grant. In February 1873, William Gouverneur Morris, the U.S. marshal for California, wrote to Grant’s private secretary, Orville Babcock, “I send to your address a couple of boxes of Manillas, commonly called ‘Philopenas’ which I imported myself from the Phillipine Islands, and beg to request, you will ask the President if he will honor me by accepting them.”

Grant was reelected in 1872, and the Republican Old Guard tried to have him nominated for a third run in 1880, after the intervening term of Rutherford B. Hayes. On June 3, 1880, he was waiting anxiously in an office in Galena when a convention wire arrived reporting that James Garfield had received the Republican nomination for president. Disappointed, Grant strode out of the office and threw to the ground what was left of the stogie he had been puffing, then extracted a new one. Leo LeBron, looking out the window of his jewelry store across the street, attentively observed this scene and sent a boy to retrieve the butt the former president had just dropped. Even as mundane an object as a cigar butt was appreciated by LeBron because of its association with the celebrated Civil War general and president of the United States, and LeBron determined to save Grant’s cigar butt (Galena-Jo Daviess County Historical Society & Museum, Galena, Illinois).

Ulysses S. Grant's smoking stand at this home in Galena, Illinois.

The years of continuous cigar smoking took their toll on Grant’s health; by the mid-1880s, when he was retired from public life, he was a dying man. But unfortunately, even in his last years, his health wasn’t the only thing in his life in ruins. He was also at this time insolvent after investing with a Wall Street swindler. Out of desperation he pledged all his possessions of value, including medals, swords, proclamations, and commissions as collateral against a loan from the industrialist William Vanderbilt, who was embarrassed about receiving these items and later offered them to Grant’s wife, but finally gave them to the Smithsonian Institution.

In the fall of 1884, Grant’s physicians did not expect him to live past the following April. Grant was dying from cancer and in great pain—he was being administered cocaine and morphine—but did live to see the following April, and beyond. He was believed to have kept himself alive by sheer will, determined to finish the personal memoirs he was writing to provide some money for his wife and children.

On July 23, 1885, the former Civil War general and U.S. president succumbed to throat cancer at the age of sixty-three at Mount McGregor in upstate New York. Just days before, however, Grant had finished his two-volume Memoirs, which became a valuable work of literature and a great historical contribution, not to mention a commercial triumph that provided substantial income for his family.

As a result of his habit of smoking cigars, Ulysses S. Grant was defeated by carcinogenic toxins in his ultimate battle, but we have today a grim reminder of his insidious habit, a brass smoking stand with the Civil War hero’s initials inscribed on the goblet that rests on top of it.

LOCATION: U. S. Grant Home State Historic Site, Galena, Illinois.