DATE: 1918.

WHAT IT IS: A fragment of the cloth that was carried as a truce flag by German soldiers to the armistice ending World War I.

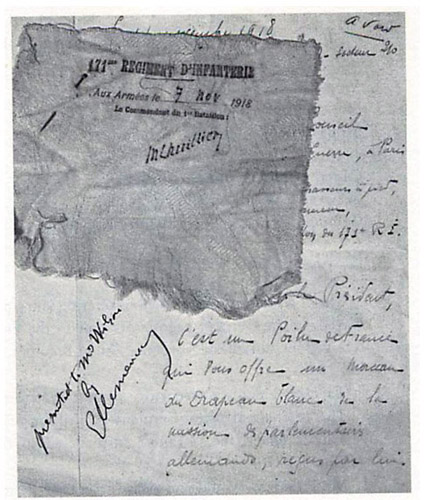

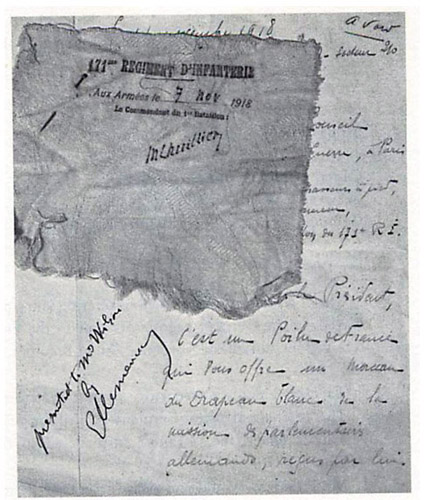

WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE: The rectangular fragment is white and measures 5 inches long and 4½ inches wide; its edges are tattered. The cloth, which has printed on it the military unit and name of the soldier who received it, as well as the date on which it was received, is pinned to a letter.

It was the first monumental conflict of modern warfare. Armies swept into combat carrying new types of sophisticated weapons. Agile submarines navigated the ocean depths, destroying in their unrestricted warfare battleships and passenger ships alike. Airplanes for the first time in war unleashed terror and death from the sky. Some 60 million soldiers from all over the globe were deployed; approximately 10 million lost their lives, with another 29 million injured, taken prisoner, or reported missing.* Warring nations wreaked havoc on one another on an unprecedented scale, and civilian populations were further devastated by rampant disease and hunger. More than four years after the commencement of World War I, the most massive international conflict in the history of humankind up to that time, its hostilities came mercifully to an end, symbolically brought to a halt by a beat-up old tablecloth.

Armistice Day was the day armies ceased their advances, the cannons stopped thundering, the bloodshed ended. It transpired on the 11th of November, 1918, pursuant to French Marshal Ferdinand Foch’s announcement to the Allied commanders that hostilities would cease on that date at eleven o’clock in the morning, and that there would be no movement of Allied troops beyond their positions on that date until further orders. For people in every corner of the globe, the long-hoped-for Armistice Day, which just a few weeks earlier had seemed impossibly far away, came into reality.

Indeed, by the end of October 1918 the Central Powers’ alliance had crumbled. Turkey and Bulgaria had already had enough of the war and wanted to negotiate a treaty with the Allies. Austria-Hungary had accepted Woodrow Wilson’s proposal to negotiate peace and in early November was given treaty terms from the Allies. The surrender of its partners was a severe blow to Germany, as the Allies could now launch attacks from inside the borders of the fallen countries.

In its weakened position, Germany’s descent to defeat came quickly. Soon the Kaiser, informed that German soldiers would no longer carry out his orders, abdicated, and the crown prince announced that he would not succeed him (both would flee to Holland). Groups of working-class people and soldiers commenced a movement that flourished across Germany and took over Berlin. The war was still being waged on the Western Front, but the Allies fought aggressively, forcing the German armies to retreat.

A patch of the World War I truce flag pinned to the letter to Georges Clemenceau that accompanied it.

The German government corresponded with the Allies on a peace negotiation. The Allies informed the Germans that Wilson’s Fourteen Points would be the foundation of peace, and that Marshal Ferdinand Foch of France would provide their representatives with the armistice terms. The world awaited the outcome of the armistice.

Four German envoys carrying a “surrender flag,” an old, stained tablecloth improvised to appear as a white flag of capitulation, were received by a French Army unit shortly after 8 P.M. on November 7 and were taken to La Capelle, where they were put on a train that took them to Rethondes. Soon after their arrival, the Germans were greeted by Allied commander in chief Marshal Foch and other high-ranking Allied commanders. The armistice terms were presented to the German delegates, who, because of the terms’ harshness—among other conditions the terms required evacuation of all occupied territories and the surrender of submarines and war supplies—requested permission to transmit them to their provisional government in Berlin, whose members convened and approved the terms on November 10. The German government informed their delegates, and at 5 o’clock the next morning, on November 11, 1918, they signed the armistice. As of that day, per Marshal Foch’s instructions to the Allied armies, hostilities ended.

The Paris Peace Conference would follow in January 1919, attended by Woodrow Wilson for the purpose of incorporating as much of his Fourteen Points as possible into the Treaty of Versailles that would be drafted at the conference. Wilson arrived in France on December 13, 1918, meeting with the premier of France and then traveling to England and Rome before the conference began the following month.

Shortly after his arrival in Paris in December, President Wilson made an official call on Georges Clemenceau at the War Office. Jubilant at the Allied victory, which the United States had greatly facilitated with its entrance into the war, the premier greeted Wilson with outstretched arms, saying, “I’m so glad to see you, Mr. President. It is so good of you to come to see me. I want to say to you right here that I am going to swear eternal friendship to you.”

During the meeting Clemenceau presumably presented the German truce flag fragment to Wilson as a token of friendship. Pinned to the flag was a letter detailing the provenance of the cloth, which had accompanied the truce fragment when it was originally given to Clemenceau. On the first page of this letter, the French premier wrote an inscription: “Presented to M. Wilson by Clemenceau.” The letter, written in French in a formal military style, reads in translation:

November 11th, 1918

La Fortelle (Belgium) Sector 210

Monsieur G. Clemenceau,

President of the Council

Minister of War, in Paris

Captain Chuillier, Infantry Officer

“Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur,”*

Commander of the 171st Infantry Regiment

Mr. President,

This is a French “Poilu”** who is offering you a piece of the white flag waved by the German negotiators sent to the French front lines and received by himself on November 7th at 8:20 PM, east of “la Capelle,” hill 234.

This was already a precursory symbol of victory.

This is where arrogant Germany begged for peace.

This is where the “Krauts” surrendered to the immortal French “Poilu.”

Mr. President, would you please accept this gesture of gratitude from the last remaining “Poilu” and last souvenir of war.

The happiest officer in France,

M. Chuillier

It was with no small measure of pride that the Wilsons received the World War I truce flag. In a letter to her family from Paris, dated Tuesday, December 17, 1918, Edith Wilson wrote of receiving the fragment. After mentioning her husband’s busy schedule and that he had rid himself of his cold, she then noted, “Yesterday he called on M. Clemenceau & when he left M. C. gave him a piece of the German flag of truce—to give to me. It looks like an old piece of table cloth, but it is such an interesting thing to have. I must stop now & write him a note to thank him.”

Edith Wilson again called attention to the World War I armistice artifact in her 1938 autobiography, My Memoir. Reminiscing about her 1918 visit to Paris, she wrote:

That same morning M. Clemenceau brought me a small piece of the flag of truce which the Germans had carried when they came to sign the Armistice terms. It is a square about two and one half inches large of what looks like an old piece of damask tablecloth. The French premier wrote a few lines on a sheet of paper and pinned the bit of cloth to it: a very gracious thought on the part of this old man. …*

While the armistice ended the hostilities of World War I, peace treaties still needed to be carved out. This would be effected through the Treaty of Versailles and other subsequent treaties, but the fealty pledged to Wilson by Clemenceau seemed to dissolve as the French premier (along with other Allied leaders) declined to support Wilson’s Fourteen Points as a foundation for peace. But Armistice Day in effect was the end of the war, and the truce flag is a symbol of the surrender of Germany, the last nation to hold out against the Allies, and the paving of the way for peace.

The truce flag returned to the White House with the Wilsons. Woodrow Wilson collapsed in 1919 after giving a speech in Pueblo, Colorado, to rally public support for his proposed League of Nations. His health in decline, he stepped down after his second term as president ended in 1921. Soon thereafter the Wilsons moved into a home at 2340 S Street, N.W., in Washington, D.C., taking with them the truce flag fragment. Woodrow Wilson died in February 1924, and his wife continued to keep the truce cloth at her home until she died in 1961, when it became a part of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Artifacts of momentous chapters of history are often simple, seemingly innocuous, everyday sorts of things. But of course it is the actions behind them that turn them into the special objects they are, extraordinary emblems of past events. In this sense, the countless human dramas, the remarkable heroism and untold suffering of a global catastrophe the likes of which had never been seen before, are invisibly woven into the extant piece of the truce flag that ended World War I.

LOCATION: The Woodrow Wilson House, Washington, D.C.

*Estimates of fatal casualties range from a few million less to a few million more.

*Cavalier of the Legion of Honor, a military award reserved for exceptional service in the armed forces, as well as for dignitaries and political figures.

**“Poilu” literally means “hairy man”; it was a term for French soldiers of World War I.

*Edith Wilson miscalculated the actual size of the small piece of cloth. She also wrote that “the French premier wrote a few lines on a sheet of paper,” when Clemenceau, in fact, wrote a brief inscription on the first page of the letter written by Chuillier.