CHAPTER 6

Western Finance, SOE Reform and China’s Stock Markets

“The debut price [of my IPO] was within expectations, but I am still a wee bit disappointed.”

Chen Biting, Chairman, China Shenhua Energy

October 10, 2007

In capital-raising terms, China’s stock markets pale in comparison to the bank loan and bond markets, but they have been instrumental in creating the country’s companies and, at the same time, lending China the veneer of a modern capitalist economy. Without them, China would have remained for an even longer time without a truly national market for capital. More importantly, its ministries would not have learned at the knee of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley how to use international corporate law and complex transfers of equity shares to build the National Team, a group of state-controlled enterprises of an economic scale never before seen in China. When in 2006 and 2007 these companies began to return home to the Shanghai market for secondary listings, they were able to use their great wealth to reward “friends and family”, those other state enterprises and agencies closely associated with the Party and allowed to take profit from the listing as investors.

This explains the comment by Shenhua’s chairman: his company’s “poor” IPO performance was, perhaps, a disappointment to his supporters. In these listings, company valuations deliberately set too low, biased lottery allocations1 and the channeling of money among powerful state entities is clearly documented for all to see. It raises the question, however, of whether China is run, as people believe, by the Communist Party or whether the National Team has subsumed the Party and the government so that it can truly be said that “the business of China is business”. China’s stock markets are not really about money (that comes from the banks): they are about power.

On October 7, 1992, a small company that manufactured minibuses completed its IPO on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), raising $80 million. This would hardly have been a landmark event except that the company was Chinese and no Chinese company had ever listed its shares outside the country, much less on the NYSE.2 Wildly oversubscribed, Brilliance China Automotive singlehandedly put China—and most certainly not the People’s Republic of China—on the map of global capital. Since that time, the clamor surrounding China’s stock markets makes it seem that New York and London have long since been eclipsed as the world’s most significant markets for equity capital.

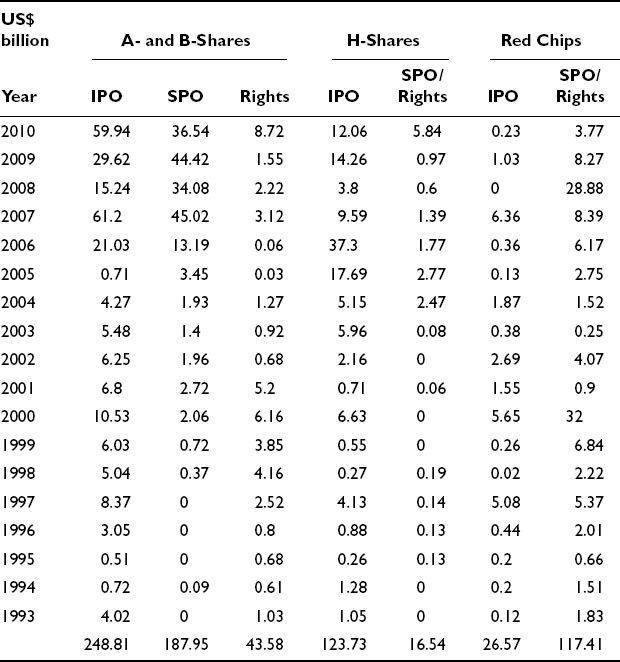

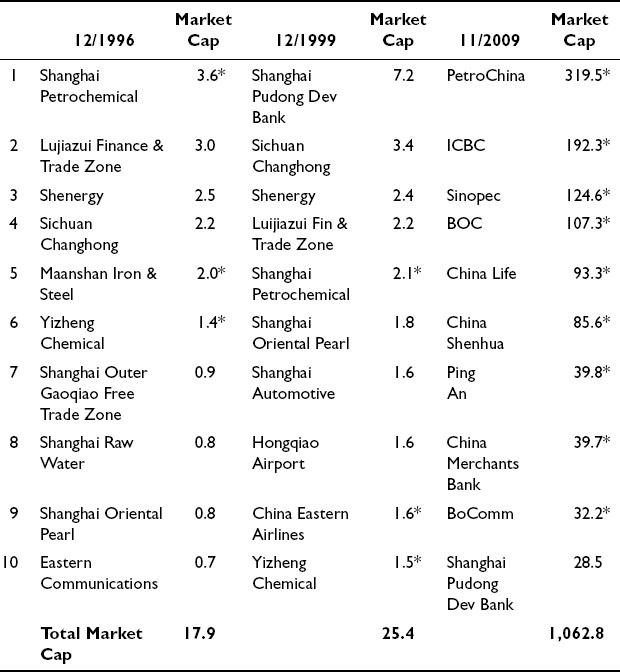

On their surface, China’s stock markets are the biggest in Asia, with many of the world’s largest companies, and more than 120 million separate accounts trading stocks in nearly 1,800 companies. Their capital-raising abilities are the stuff of legend (see Table 6.1). According to data from Bloomberg, since January 2006, half of the world’s top 10 IPOs were Chinese companies raising over US$45 billion. It is not uncommon for new issues in Shanghai to be 500 times oversubscribed, with more than US$400 billion pledged for a single offering. The scale of China’s companies since 1990 has increased exponentially. In 1996 the total market capitalization of the top 10 listed companies in Shanghai was US$17.9 billion; by year-end 1999, this was US$25.3 billion and, 10 years later, US$1.063 trillion! Like everything else about China, the simple scale of these offerings and the growth they represent at times seems staggering.

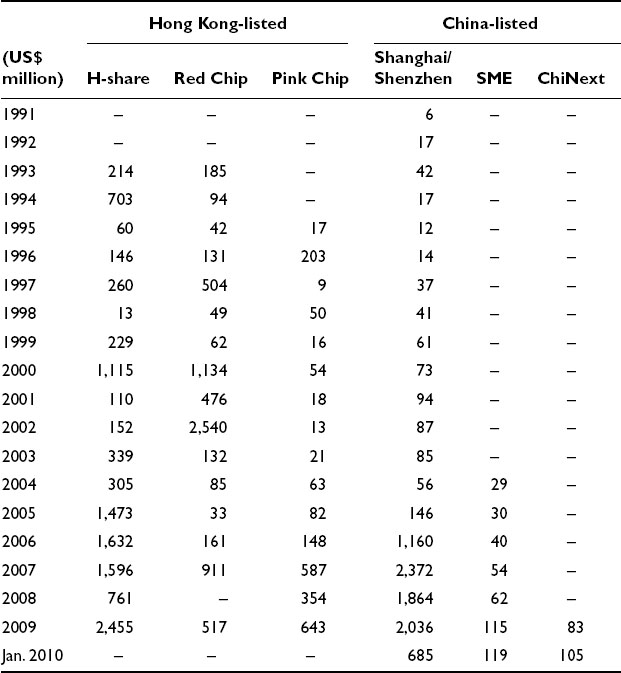

TABLE 6.1 Funds raised by Chinese companies, China and Hong Kong markets

Source: Wind Information and Hong Kong Stock Exchange to September 30, 2010

Note: US$ at prevailing rates; Hong Kong GEM listings not included; No B-share issuance since 2000.

Of course, the scale of the profit involved can also be huge. In 2009, Chinese companies raised some US$100 billion, of which 75 percent was completed in their domestic markets of Shanghai and Shenzhen. Underwriting fees in China are around two percent, suggesting that China’s investment banks (and only the top 10 at best participate in this lucrative business) earned fees totaling US$1.5 billion. This amount, as large as it, pales in comparison to the amount collected in brokerage fees. For example, on a single day, November 27, 2009, A-share trading on the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets reached a historic high of over RMB485 billion (US$70 billion) in value. For a market that doesn’t allow intra-day trading, that turnover is truly impressive—more than double the rest of Asia, including Japan, combined. Brokerage fees for that one day alone totaled around US$210 million, spread between 103 securities companies. With all that money up for grabs (and a clear preference for domestic over foreign markets by Chinese companies) it is no wonder that there is so much noise surrounding China’s stock markets—investment bankers anywhere are hardly known for being self-effacing and China’s are no different.

Observers are also very impressed with the market’s infrastructure. Like the inter-bank debt markets, the mechanics of the stock exchanges are state-of-the-art, with fully electronic trading platforms, efficient settlement and clearing systems and all the obvious metrics such as indices, disclosure, real-time price dissemination and corporate notices. The range of information provided on exchange websites is also impressive and completely accurate, but all of this is only a part of the picture. China’s stock exchanges are not founded on the concept of private companies or private property; they are based solely on the interests of the Party. Consequently, despite the infrastructure, the data and all the money raised, China’s stock markets are a triumph of form over substance. They give the country’s economy the look of modernity, but like the debt-capital markets, the reality is they have failed to develop as a genuine market for the ownership of companies.

The engine at the heart of the debt markets is the valuation of risk and this is missing in China because the Party controls interest rates. Similarly, the heart of a stock market is the valuation of companies and this is also missing in China because the Party controls the ownership of listed companies. Private property is not the central organizing concept of the Chinese economy; rather, the central organizing concept is tied to control and ownership by the Communist Party. Given this basic premise, markets cannot be used as the means to allocate scarce resources and drive economic development. This role belongs to the Party which, to achieve its own ends, actively manipulates both the stock and debt markets. As shown in the previous two chapters, the debt market cycle takes place within a regime of controlled interest rates and suppressed risk valuations that are the corollary to the Party’s control over the allocation of capital. The stock markets, in contrast, are vibrant, but do not trade securities that convey an ownership interest in companies. What these securities do represent is unclear, other than that they have a speculative quality that permits gains and losses from trading and IPOs.

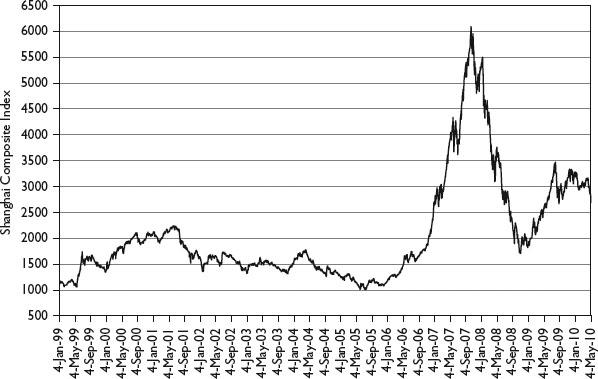

In China, the stock and the real-estate markets have evolved into controlled outlets for surplus capital seeking a real return and, for the most part, this capital is controlled by agencies of the state. Stocks and real estate are the only two arenas in China that, although subject to frequent administrative interference, can produce rates of return greater than inflation. The huge run-up in the Shanghai Index in 2007 is an example of this (see Figure 6.1): the significant appreciation of the RMB that year drew in large volumes of “hot money” that was then parked in stocks, drawing the index ever higher. Like developed markets, China’s stock markets operate rationally, but only within a framework shaped by the distorted and biased initial conditions set by the state. Their substance cannot and will not change unless these boundary conditions change. This would require outright and publicly accepted privatization—a highly unlikely prospect in any prognosticator’s near- or medium-term futures.

WHY DOES CHINA HAVE STOCK MARKETS?

Why would China’s government in 1990 of all times decide to create stock markets? The decision to open the Shanghai exchange was made in June 1990, just a year after Tiananmen, and it opened at year-end in the midst of malicious political mudslinging concerning whether the reforms of the 1980s belonged to what are commonly referred to in China as “Mr. Capitalism” or “Mr. Socialism.” The markets were not needed from the viewpoint of capital allocation. Then, as now, the Big 4 banks provided all the funds the state-owned sector could possibly want. The reason for establishing stock markets was not related to political expediency or the capital requirements of SOEs. Rather, Beijing decided to establish stock markets in 1990 largely from an urge to control sources of social unrest and, in part, because of the inability of its SOEs to operate efficiently and competitively. The stock-market solution to both issues was purely fortuitous. If there had not been a small group of people sponsored by Zhu Rongji who had plans for stock markets already drawn up, China today could have been quite different. Moreover, had these people retained authority over market development into the new century, China could have been quite different in yet another way.

“Share fever” and social “unrest”

In the 1980s, China’s stock markets arose for the same reasons as stock markets in Western private economies: small, private and state-owned companies were starved of capital and small household investors were seeking a return. The idea of using shares to raise money sprang up simultaneously in many parts of the country and, given the relaxed political atmosphere of the times, the ideas were allowed to take shape.3 Despite Shanghai’s raucous claims to be the country’s financial center, there is no argument but that Shenzhen was the catalyst to all that has come after. Its proximity and cultural similarity to Hong Kong were major factors behind this. The key year was 1987, when five Shenzhen SOEs offered shares to the public. Shenzhen Development Bank (SDB), China’s first financial institution (and first major SOE) limited by shares, led off in May and was followed in December by Vanke, now a leading property developer. Their IPOs were undersubscribed and drew no interest. The retail public’s indifference to SDB’s IPO even forced the Party organization in Shenzhen to mobilize its members to buy shares. Despite this support, only 50 percent of its issue was subscribed.

The fact is that after more than 30 years of central planning, near-civil war and state ownership, the understanding of what exactly an equity share was had been lost in the mists of pre-revolution history. Where securities called “shares” existed, investors thought of them as valuable only for the “dividends” paid; people bought them to hold for the cash flow. There was no awareness that shares might appreciate (or depreciate) in value, and so yield up a capital gain (or loss). So the market was understandably tepid for the bank’s IPO and it was also unprepared for events that followed payment of the first dividend in early 1989.

The SDB’s dividend announcement in early 1989 marked a major turning point in China’s economic history and it should be recognized as such. The bank was very generous, awarding its shareholders—largely state and Party investors—a cash dividend of RMB10 per share and a two-for-one stock dividend. In the blink of an eye, those who had bought the bank’s shares in 1988 for about RMB20 enjoyed a profit several times their original investment. Even so, a small number of shareholders failed to claim their stock dividends and the bank followed procedures to auction them off publicly. The story goes that when one individual suddenly appeared at the auction, offered RMB120 per share, and bought the whole lot, people got the point: shares were worth something more than simple face value. As this news spread in Shenzhen, a fire began to blaze. The bank’s shares, as well as the few other stocks available, sky rocketed in wild street trading. SDB’s shares jumped from a year-end price of RMB40 to RMB120 just before June 4, 1989, and despite the political trouble up north, ended the year at RMB90.

Armed with this new insight, China’s retail investors set off a period of “share fever” centering on Shenzhen and gradually extending to Shanghai and other cities such as Chengdu, Wuhan and Shenyang where shares were traded. In the end, Beijing forced local governments to take steps to cool things down. Restrictions eventually took hold, leading to a market collapse in late 1990. Even so, investors had learned the lesson of equity investing: stocks can appreciate. But Beijing had also learned a lesson: stock trading could lead to social unrest. The decision to establish formal stock exchanges was made in the midst of “share fever” in June 1990 and the Shenzhen and Shanghai exchanges opened later the same year.

State-owned enterprise reform via incorporation

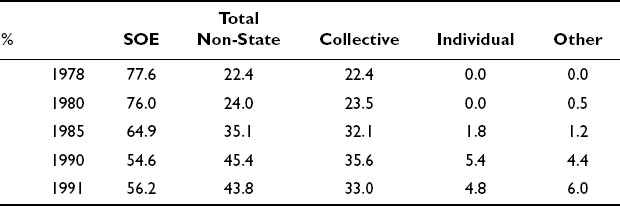

Of course, Beijing could simply have forbidden stocks and all associated activity, but it didn’t. The reason for this can be found in a policy debate about the sources of dismal SOE performance. Despite the government’s lavishing of resources and special policies of all kinds on SOEs during the 1980s, China’s emerging private sector had left them in the dust.

The annual growth rates of private industry exceeded 16 percent as against only seven percent for the state sector (see Table 6.2). As a consequence, the private sector had increased its share of industrial output nationally from 22 percent to more than 43 percent during the decade. For the Party, this was simply not acceptable and, in fact, it is still not acceptable. Then (as now) the Party expected the state sector to dominate, and in the late 1980s, it desperately needed to find an effective way to strengthen the sector, if not to stimulate better SOE performance.

TABLE 6.2 Share of total industrial output by ownership

Source: China Statistical Yearbook, various

From 1985, a group of research students and staff at the State Committee for the Reform of the Economic System (SCRES) had developed a critique of state planning and state ownership of all aspects of industrial production. This group provides a clear insight into who among today’s Party leadership belong to the market reformers. The SCRES group included Guo Shuqing (now Chairman of CCB), Lou Jiwei (now Chairman of CIC), Zhou Xiaochuan (now Governor of the PBOC), Li Jiange (now Chairman of CICC and previously Zhu Rongji’s personal assistant) and Wu Jinglian (Zhu Rongji’s favorite economist), all of whom today continue to make contributions to China’s market-reform effort. Based on their work, as well as on ideas brought back from New York by Gao Xiqing (now CEO of CIC), Wang Boming (Founder and Publisher of Caijing  magazine) and others, by late 1988, the State Council and SCRES had initiated a project that would lead Beijing to co-opt the 1980s experiment with stocks for the benefit of SOEs.

magazine) and others, by late 1988, the State Council and SCRES had initiated a project that would lead Beijing to co-opt the 1980s experiment with stocks for the benefit of SOEs.

At the historic Xizhimen Hotel Conference of December 1988, the framework for China’s future stock markets was set. Discussion centered only on the question of how to improve the performance of SOEs and the recommendations related only to SOEs. The conference report concluded that the critical conditions to proceed with what was called the “shareholding system experiment” included: 1) avoidance of privatization; 2) avoidance of the loss of state assets; and 3) the guarantee of the primacy of the state-owned economy. If such objectives could be achieved, the conference concluded, the new form of companies limited by shares was attractive for two reasons. First, the corporate structure of a company limited by shares could address the perceived problem of excessive government involvement in enterprise management. Second, if properly managed, the sale of a minority stake in such a company could raise capital from sources other than the state budget and the PBOC printing press.

Efforts to obtain State Council approval of the conference’s proposal prepared by the SCRES came to nothing in 1989, but a year later, the “social unrest” generated by a populace trying to get rich revived the reformers’ suggestions. The government in Beijing saw exchanges as a way to close the street markets by moving them “inside the walls.” In May 1990, the State Council approved an updated version of the SCRES recommendations that included: 1) no individual investors; only enterprise investment in the share capital of other enterprises; 2) no further sale of shares to employees; 3) development of OTC markets limited to Shanghai and Shenzhen alone; and 4) no new public offerings. On June 2, just a month later, the State Council gave the go-ahead to the formal establishment of the two securities exchanges.

So the opening of the Shanghai Stock Exchange in December 1990 and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange in July 1991 were highly symbolic historical events—but not for the reasons usually given. Outside observers saw them as signs that China had shrugged off the disaster of Tiananmen, picked up the torch of reform and was again embarking on the brave new world of capitalism when, in fact, the exchanges were opened to put an end to free private-capital markets. In their place, the exchanges and entire experiment were harnessed in support of the development of state enterprises only. What China got as a result, however, was of historical importance, but not in the way the Party had foreseen at the time.

Had it not been for two events in 1992, however, even this state-centric version of stock markets might not have eventuated and China might have developed in a very different direction. First, Deng Xiaoping in early 1992 affirmed the value of stock markets, which gave rise to the country’s first huge equity boom. The political cover Deng gave for supporters of this experiment with modified capitalism was perhaps the critical political decision that led to the China we know today. But Zhu Rongji, then vice-premier in charge of banking and finance, also contributed greatly to China’s future development when he agreed to open international markets and their limitless capital to China’s SOEs. The first decision led to China’s first truly national capital market; the second let in the ideas and financial technologies that created its great National Champions. Together, these decisions led to a centralization of financial power in Beijing that it had never had before, and changed—if not destroyed—old government institutions.

A national financial market and beyond

What did Beijing own in 1979? The answer is, everything and nothing. In some sense, it owned the entire economy, with an estimated official GDP that year of RMB406.2 billion (US$261 billion). The country’s industrial landscape, however, was bare of anything resembling enterprises with economies of scale and China had extremely limited financial resources to invest. Over the course of the 1980s, neither the national budget nor the banking system could adequately support even the 22 major industrial projects designated in state plans as critical national investments. Given the dearth of state-supplied capital, it is no wonder that other ideas emerged.

Aside from the national budget, the banks were the primary providers of capital, but their capacity was very limited. Organized on the lines of the administrative hierarchy reaching to Beijing, the provincial branch bank was the key to this system and it operated independently of other provincial branches. Limited to a single province, its deposit base was geographically circumscribed, forcing it to rely either on a slowly growing national inter-bank market from 1986 and central budget grants, or on intra-provincial government, retail and SOE deposits. The central government for its part had limited taxable resources and also lacked the financial technology that would help it raise large amounts of capital by issuing bonds: a functioning bond market did not exist, nor was one permitted.

The Yizheng Chemical Fiber project in Jiangsu, one of the 22 key projects, is a case in point. This ambitious project became famous in 1980 when its sponsor, the Ministry of Textiles, approached China International Trust and Investment (CITIC) for funding it could not source elsewhere, either from banks or from the MOF. CITIC, led by Rong Yiren (its founder and the survivor of a successful pre-revolution Shanghai industrial family), proposed an international bond issue in Japan to raise 10 billion yen (US$50 million). This novel—many said counter-revolutionary—idea caused a political furor. Ultra-nationalists claimed it was a disgrace to rely on capitalist countries, much less Japan, to fund Chinese projects. It took an entire year for the political finger-pointing to die down and only after it had become clear that the money, in truth, could be found nowhere else in the country. The State Council approved the bond and it was successfully issued in 1981. The point is that such a small amount could not be sourced domestically even for a critically needed project. Yizheng was later one of the first nine candidates for overseas listing chosen by Zhu Rongji in 1993.

Several years later, the MOF was able to sell limited amounts of “special” bonds to fund similar industrial projects. For example, in 1987, it raised US$1.5 billion in support of new refinery projects at five centrally owned enterprises and, in 1988, another US$1 billion equivalent for projects at seven steel companies. Again the funds were limited in scale, especially given the capital intensity of such industries. The inability of central government, at this point 30 years into its revolution, to raise large amounts of capital is not unique to modern China. One scholar argues persuasively that the very absence of a national capital market and its ability to mobilize large amounts of money explains China’s historical inability to develop economically beyond small-scale manufacturing.4

Given this dearth of capital, it is easy to understand why, despite ideological compunctions, local governments from the early 1980s were so attracted to the idea of stock markets. The image of Zhu Rongji finding the treasury bare on his appointment as Mayor of Shanghai in 1988 is priceless; he rapidly became the political godfather to the movement to establish formal stock exchanges. But like the banking system, the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges at their inception were geographically limited to listing local companies and relying on local retail investors. This changed rapidly, however, and by 1994, both had become markets open to issuers and investors on a national basis. This made it possible for provincial governments to raise incremental amounts of capital on top of what local banks and taxes could provide. Although small by international standards, the top 10 listed companies in Shanghai were by 1996 larger than any of their predecessors (see Table 6.3) and three years later larger still. It is noteworthy, in light of the discussion later in this chapter, that the top 10 companies in 2009 were all financial institutions and oil companies.

TABLE 6.3 Top 10 Shanghai-listed companies: Then and now (US$ billion)

Source: Shanghai Stock Exchange and Wind Information

Note: Capitalization calculated based on domestic market practice, which includes all domestic company shares but excludes overseas-listed shares; *denotes additional overseas listing in Hong Kong or New York.

These companies, however, are the exception; the vast majority of companies listed on the domestic exchanges were tiny, with market capitalizations of under US$500 million. In the primary markets, as well, A-share IPOs on the whole remained small throughout the 1990s. With the exchanges operating only from 1992, one could hardly expect Chinese markets to reach their full size overnight or even by the end of their first 10 years. Nonetheless, the domestic markets would have remained sideshows for far longer had Zhu Rongji not permitted Chinese companies to list their shares on overseas markets.

This decision led to the dramatic growth of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKSE) from its position as a small regional exchange in 1993 to a global giant in the twenty-first century. From its boast in 1993 of hosting IPOs of as much as US$100 million for local taipans within 10 years, thanks to Zhu, it was raising billions of dollars for Chinese SOEs. By approving the first batch of nine so-called H-share companies, Zhu changed Hong Kong’s game entirely. His internationalism accounts for the huge capital raisings and market capitalizations of the top 10 listed companies in 2009. Of these companies, nine were also listed either in Hong Kong or New York. In the period 1993–2009, Chinese SOEs raised US$262 billion in new capital from the international markets, with the year 2000 marking the turning point (see Table 6.4). For the first time in its history, China and its companies had access to the financial techniques and markets that enabled them to raise meaningful amounts of capital. They took these techniques and brought them back at last to Shanghai.

TABLE 6.4 Average IPO size per listing class

Source: Wind Information and Hong Kong Stock Exchange

China Telecom: God’s work by Goldman Sachs

How did China go from having small-scale companies that banks would hardly look at to ones raising billions of dollars in New York in just 10 years? If there is a single reason, it is the persistent enthusiasm for the China story among international money managers combined with their willingness to put vast amounts of money down on it. Their response to the tiny (and bankrupt) Brilliance China US$80 million IPO in 1992 was just as wild as that for China Telecom’s US$4.2 billion IPO in 1997, but the scale of the two companies and the money couldn’t have been more different. International markets introduced Chinese companies to world-class investment bankers, lawyers and accountants and brought their legal and financial technologies—the entire panoply of corporate finance, legal and accounting concepts and treatments that underpin international financial markets—to bear on China’s SOE-reform effort. What happened when aggressive and highly motivated investment bankers and lawyers interacted with government officials at all levels up to and including the State Council altered the course of China’s economic and political history and is the subject of a different book.

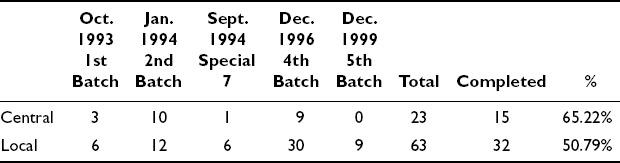

This technology transfer greatly strengthened Beijing’s control over the money-raising process, but, strangely enough, in the end weakened the government by strengthening its companies. In 1993, at the start of China’s IPO fever, Beijing was only one of many government entities owning companies competing for the right to raise capital overseas. There was a bureaucratic process at the center of which was the newly established China Securities Regulatory Commission. This heavily lobbied agency screened the listing applications of all local governments and central ministries to come up with an approved list of candidates for which foreign investment banks were allowed to compete for IPO mandates (see Table 6.5).

TABLE 6.5 Ownership of listing candidates for overseas IPOs

The early batches included what were then, in fact, China’s best enterprises (for example, First Auto Works, Tsingtao Beer and Shandong Power). None, with the exception of the beer company, had any international brand recognition. The truth is that no one outside of China had ever heard of these companies, knew what they did, or where they were located: China’s SOEs were completely virgin territory for the world’s investment banks. Had anyone ever heard of Beiren Printing, Dongfeng Auto or Panzhihua Steel? Not only were these companies unknown, there were not many of them. By the time calls went out for the fourth and fifth batches, provincial governments came up empty-handed; there simply were very few companies with the economic scale and profitability required for raising international capital. The fourth batch consisted largely of highway and other so-called infrastructure companies, while the fifth batch introduced farmland into the mix. Even Wall Street bankers could not find a way to list what was not even a working farm.

The fact of the matter was that there were few good IPO candidates. Enterprises owned by the central government had enjoyed access to the best financial and policy support since 1979 and this accounts for their reasonably high IPO completion rates. Even so, for the period from 1993 to 1999, they accounted for only one-third of the total of 86 candidates. There were very few that could, even with the best financial advice, meet the requirements of even the most enthusiastic international money managers and only 51 percent of the candidate companies succeeded in listing overseas. By 1996, China’s effort to use stock-market listings to reform its SOEs seemed to have hit the wall. Then came the IPO of China Telecom (now known as China Mobile).

In October 1997, and despite the evolving Asian Financial Crisis, China Mobile (HK) Co. Ltd. completed its dual New York/Hong Kong IPO, raising US$4.5 billion—some 25 times the average size of the 47 overseas-listed companies that had gone before. This kind of money made everyone sit up and pay attention: underwriting fees alone were said to be over US$200 million. If China was, in fact, full of small companies, as the earlier international and domestic listings show, then where had this one come from? The answer is simple, yet complicated: China Mobile represented the consolidation of provincially owned and run industrial assets into what is now commonly called a “National Champion.” This transaction demonstrated to Beijing how it could overcome the regional fragmentation of its industrial sector and, with huge amounts of cash raised internationally, create powerful companies with national markets.

The creation of such new companies out of the grist of the old SOEs would have been impossible without the legal concepts and financial constructs of international finance and corporate law that are the foundation of all modern corporations and the capitalist system itself. In fact, while the capital raised was important in building today’s China, the most important thing of all was the organizational concept that permitted true centralization of ownership and control. The New China of the twenty-first century is a creation of the Goldman Sachs and Linklaters & Paines of the world, just as surely as the Cultural Revolution flowed from Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book.

In the absence of new listing candidates and in the midst of the ongoing technological revolution in the US, Goldman Sachs aggressively lobbied Beijing using the very simple but powerful idea of creating a truly national telecommunications company. Such a company, it was argued, could raise sufficient capital to develop into a leading global telecommunications technology company. The ideas had already been used for the so-called Red Chips that were briefly all the rage among investment bankers in early 1997. Instead of creating holding companies owned by single municipal governments that held its breweries, ice-cream plants, auto companies and, in the famous instance of Beijing Enterprise, the Badaling section of the Great Wall of China, why not acquire and merge provincial telecom entities into a single company owned by the central government?

Given the strong centrifugal forces in the country, this required real political will and power that the imperious Minister of Posts and Telecommunications (MPT), Wu Jichuan, could supply in full. It also required the support of a central government that saw economic scale as a critically important building block to international competitiveness and that was also comfortable with the legal enforceability of shareholder rights (at least its own) in Western courts. China Mobile’s wildly successful IPO catalyzed a series of blockbuster transactions that put Beijing front and center in the world’s capital markets. If there is a single reason why the world is in awe of China’s economic miracle today, it is because international bankers have worked so well to build its image so that minority stakes in its companies could be sold at high prices, with the Party and its friends and families profiting handsomely. The China Mobile transaction was the first big step in this direction.

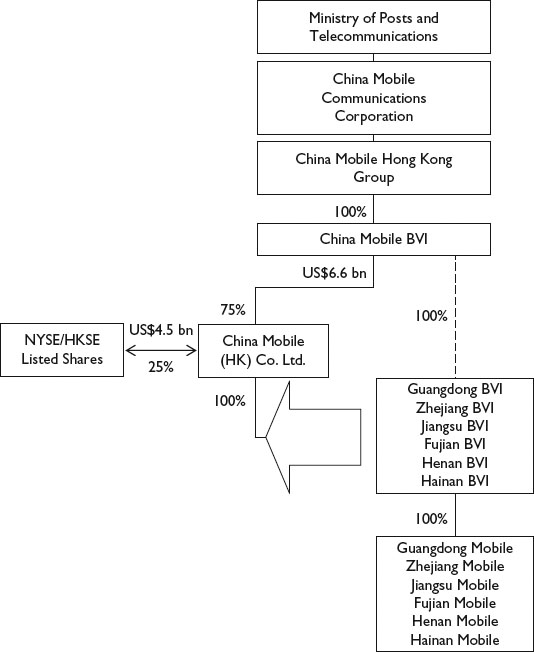

How this historic US$4.5 billion IPO was put together is shown in Figure 6.2. Simply put, a series of shell companies were created under the MPT, the most important of which was China Mobile Hong Kong (CMHK). CMHK was the company that sold its shares to international investors, listed on the New York and Hong Kong stock exchanges, and used the capital plus bank loans to buy from its own parent, China Mobile (British Virgin Islands) Ltd. (CM BVI), telecom companies operating in six provinces.

FIGURE 6.2 China Mobile’s 1997 IPO structure

The key point that stands out in this transaction is that a subsidiary raised capital to acquire from its parent certain assets by leveraging the future value of those same assets as if the entire entity—subsidiary plus parent assets—existed and operated as a real company. The value of the provincial assets, as far as the IPO goes, was based on projected estimates of their future profitability as part of a notional company that was compared to the financial performance of existing national telecoms companies operating elsewhere in the world. In other words, the estimates were based on the assumption that CMHK was already a unitary operating company comparable to international telecom companies elsewhere. This most certainly was not the case in China: prior to its IPO, CMHK was a shell holding company that existed only on the spreadsheets of Goldman’s bankers. The IPO, gave it the capital to acquire six independently operating, but as yet unmerged, subsidiaries. So even at this point, China Mobile could be said to exist only as a paper company, but with a very real bank account.

This was not the IPO of an existing company with a proven management team in place with a strategic plan to expand operations. It would be much closer to the truth to say that this was an IPO of the Ministry of Post and Telecommunications itself! But international investors loved it and two years later, in 2000, a similar transaction was carried out in which CMHK raised a total of $32.8 billion from a combination of share placement ($10.2 billion) and issuance of new shares ($22.6 billion). This massive injection of capital was used to acquire the MPT’s telecom assets in a further seven provinces. As a result of these two transactions, China Mobile had reassembled the MPT’s mobile communications business in 13 of China’s most prosperous provinces in the form of a corporation that replaced a government agency. What happened to the US$37 billion raised after CMBVI was paid is unknowable since it is a so-called private unlisted entity and is not required to make public its financial statements.

The significance of this deal ripples down to this day over a decade later. First, as was the case for the original 86 H-share companies, the government could have simply incorporated each provincial telecom authority (PTA) and sought to do an IPO for each. This would no doubt have greatly benefited local interests and ended up creating many regional companies. The amount of money to be raised in aggregate, however, would in all probability have paled in comparison with China Mobile and there was no certainty that any local firm would have developed a national network. More importantly, the new structure conceptually enabled the potential consolidation of entire industries, making possible the creation of large-scale companies that might someday be globally competitive. Today, China Mobile is the largest mobile-phone operator in the world, with over 300 million subscribers and operating a network that is the envy of operators in developed markets.

Second, and equally important, the money raised was new money, not re-circulated Chinese money from the budget, the banks, or the domestic stock markets. Third, the creation of this structure made possible the raising of further massive amounts of capital simply by injecting new PTAs (or any other “asset”). The valuation of such assets was purely a matter of China’s negotiating skills, flexible valuation methodologies employed by the investment banks and demand in the international capital market. In the case of the acquisition in 2000, foreign investors paid a premium of 40–101 times the projected future value of China Mobile Hong Kong’s earnings and cash flow. This was truly pulling capital out of the air! Fourth, this new capital was without doubt paid back into the ultimate Chinese parent, CMCC, giving it vast amounts of new funding independent of budgets or banks. More importantly, the restructuring took what were relatively independent provincial telecom agencies originally invested in by a combination of national and local budgets and allowed China Mobile to monetize them by means of an IPO priced at a huge multiple of the original value. The ability to deploy such capital at once transformed CMCC into a potent force—political as well as economic.

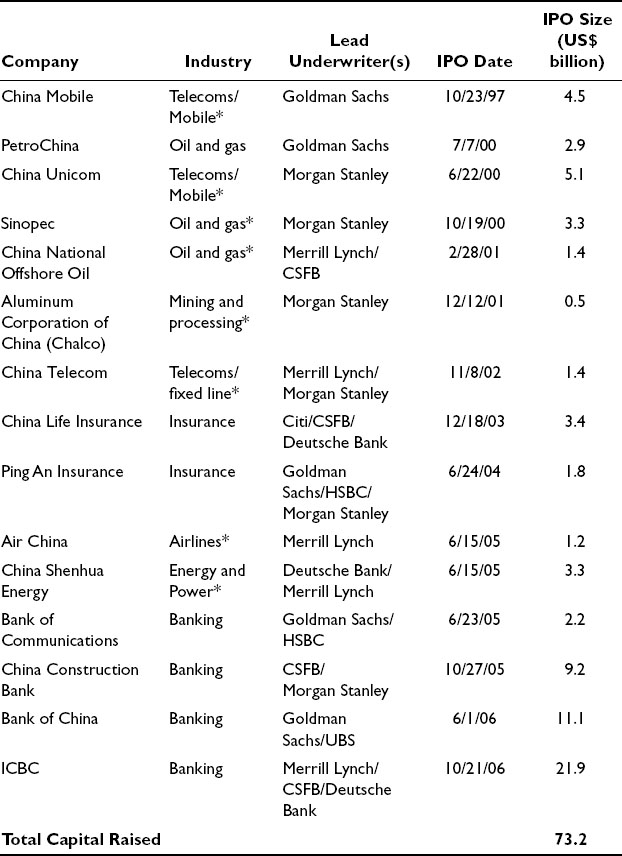

Why wouldn’t Beijing enthusiastically embrace these Western financial techniques when the foreigners were making the Party rich and China seem omnipotent? In the ensuing years, China’s “National Team” was rapidly assembled (see Table 6.6) and a similar approach was used to restructure and recapitalize China’s major banks, as described earlier. It need hardly be said that this list includes only central government-controlled companies: Beijing kept the goodies for itself.

TABLE 6.6 The National Team: Overseas IPOs, 1997–2006

Source: Wind Information

Note: * denotes company parent Chairman is on the central nomenklatura list of the Organization Department of the Communist Party of China.

None of this would have been possible if it had not been for international, particularly American, investment bankers. Over the period 1997–2006, bankers and professionals from a small number of international legal and accounting companies played major roles in the creation of entire new companies. These companies were created out of industries that were fragmented, lacking economies of scale, or, in the case of the banks, even publicly acknowledged as being bankrupt. The investment banks put their reputations on the line by sponsoring these companies in the global capital markets, introducing them to money managers, pension funds and a myriad of other institutional investors. Supported by global sales forces, industry analysts, equity analysts and economists, the banks sold these companies for China. Sometimes investors were so excited they didn’t even have to: for the first time, global investors had the opportunity to invest in true proxies of China’s national economy.

Simply put, international financial, legal and accounting rules provided the creative catalyst for China’s vaunted National Team. Even more important, their professional expertise and skills put Beijing and the Communist Party of China in the driver’s seat for a strategic piece of the Chinese economy for the first time ever: the central government and the Party’s Organization Department own the National Team.

1 Shares in the public offering are allocated to investors by means of a lottery process.

2 Of course, the authors are well aware that the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank and AIG are companies with deep Chinese roots, but they were not Chinese owned.

3 For more details on how the demand for capital gave rise to stock markets spontaneously in China during the early 1980s, see Walter and Howie 2006: Chapter 1.

4 See David Faure, China and Capitalism: A history of business enterprise in modern China. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006.