Part One

THE HEAVENS AND THE EARTH

What indeed is more beautiful than heaven, which of course contains all things of beauty?

– Nicholas Copernicus, On the Revolutions (1543)1

The two chapters of Part One address three intellectual revolutions which transformed the way in which the cosmos was conceived. The first argues that before Columbus discovered America in 1492 there was no clear-cut and well-established idea of discovery; the idea of discovery is, as will become apparent, a precondition for the invention of science. The second shows that the discovery of America disproved a central claim about the world which had been generally accepted before 1492, that there could be no antipodean land masses, for South America lay halfway around the globe from parts of the Old World. An immediate consequence, therefore, which is the subject of Chapter 4, was a radical transformation in the understanding of how the Earth is constructed: the emergence of the concept of the terraqueous globe. This was a crucial precondition for the astronomical revolution which followed. The chapter goes on to reappraise what Thomas Kuhn called the Copernican revolution. As we will see, the Copernican revolution was delayed until the seventeenth century: very few sixteenth-century astronomers accepted Copernicus’s claim that the Earth revolves around the sun instead of standing still at the centre of the cosmos. The real revolution in astronomy came with Tycho Brahe’s nova, with the abandonment of belief in the crystalline spheres, and with the invention of the telescope. The key date is not 1543 but 1611.

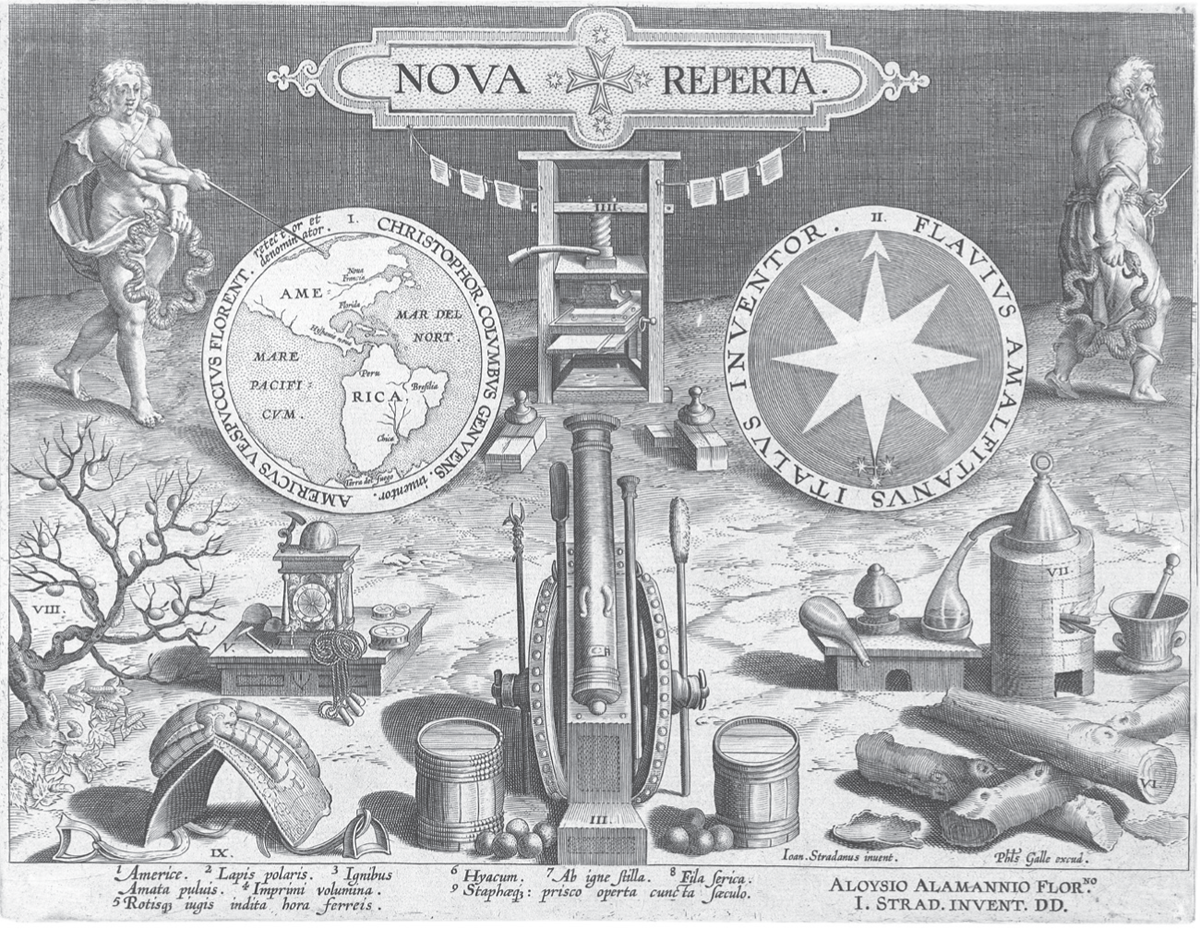

The title page of Johannes Stradanus’s New Discoveries (Nova reperta, c.1591) summarizes the knowledge that marks off the modern world from the ancient. Pride of place is given to the discovery of America and the invention of the compass, with, between them, the printing press. Also present are gunpowder, the clock, silk weaving, distillation and the saddle with stirrups.