(543–615)

November 23

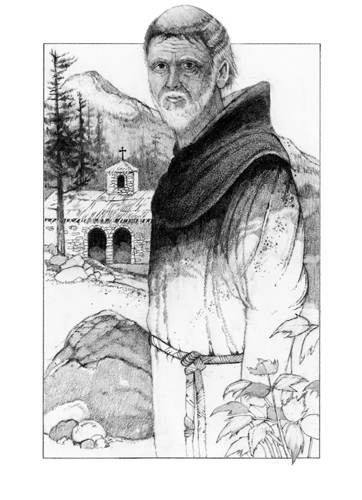

Autumn was at its peak. The elderly monk could feel its twinge in his bones. The trees were still too thick with leaves for him to see what was going on in the valley below, but Columban knew that his monks were there. Today they would be working in the vineyards and olive groves, getting ready for the days of icy winds and swirling snows that would soon be coming. There wouldn’t be much food this winter, but the monks fasted so often that their supplies were sure to last until spring.

How are the other monasteries, those beyond Italy, doing? the old man wondered. He thought of each one, hundreds of miles to the northwest, hidden among the forested mountains of Gaul. It had been years since he had seen them. The monk pondered his memories in silence, and then turned back into his cave. During the past two years he had spent many hours at prayer in this retreat. Now he felt he would soon leave the cave for good.

Columban had lived a long and active life. He thought back over the years to his youthful days in distant Ireland, the land of his birth. He remembered how difficult it had been to leave home. In his imagination, he heard again his mother’s tearful voice begging him not to go. He relived his journey to the island of Cluain, where he had continued his studies of Latin and Scripture at the monastery. Then he had decided to become a monk himself—a decision that had changed the course of his life.

Columban joined the monastery at Bangor and was ordained a priest. For nearly thirty years he tried as hard as he could to belong only to God. He finally realized that there was one more sacrifice that God was asking him to make. He went to his abbot and begged, “Father, please send me as a missionary to Gaul.”

“I would rather have you remain here, Columban,” Abbott Comghall replied. “But I’ll pray about it. I want you to do God’s will.”

Soon God did inspire Comghall to let Columban go to Gaul. The abbot even sent twelve monks with him!

Columban had lived a long and active life.

The little band of monks packed a few books and sacred vessels for Mass and set sail for the European continent. From Brittany, where more men joined them, they started out for eastern Gaul, trudging along crumbling Roman roads that were almost blocked by thick forests. The forests were dangerous for many reasons. Lurking in them were runaway soldiers and slaves, as well as gangs of thieves—not to mention wild animals. The once glorious Roman Empire had fallen into chaos. Gaul itself was divided among three kings who were Christian in name only. There were signs of war and destruction everywhere.

At last, Columban and his companions were welcomed into Burgundy, the territory of King Gunthram. There, in a wild and desolate valley, they converted an abandoned fort into a monastery and an old pagan temple into a chapel.

The monks soon became friends with the peasant farmers in the area. Several young men asked to enter the monastery and become monks.

The monks led a hard life. They spent long hours teaching and instructing the people. It had been many years since there had been any schools in that region. For food, the monks gathered wild plants, berries, and roots. They raised crops and fished in the nearby lakes. They spent hours praying together in the chapel or off alone on the hillsides. As a penance, they would often pray for long periods with their arms stretched out in the form of a cross.

Soon it was time to start another monastery. Columban and some of his monks followed the river downstream until he came to the ruins of Luxeuil, a Roman town that had been destroyed by the Huns. “Here is where we can build,” he told his companions.

The monks happily set to work. They cut away underbrush, felled trees, and hauled stones. They rebuilt the town walls and constructed a church, a school, and a number of little one-room houses in which the monks would live. Not long afterward, so many men began to join them that they had to build another monastery a short distance away, in Fontaines.

Soon the three communities in Gaul housed sixty monks and over two hundred students, mostly noblemen’s sons. The boys came to the monastery to be educated in the usual subjects, but they also learned self-discipline, honesty, and kindness. People from the surrounding villages would come to spend a few weeks with the monks too. They had the opportunity of receiving the sacrament of Reconciliation and learning more about living the Christian life. It had been many years since some of the peasants had talked to a priest!

Now, almost sixty years after St. Benedict had written his rule for monks, Columban wrote his own rule. Columban’s rule stressed the need for frequent fasting and other physical penances that the Irish monks and their disciples had always considered important. But the main purpose of monastic life, Columban wrote, was to learn to love God with all one’s mind, heart, and strength, and to love one’s neighbor as oneself for the love of God.

“We must think often about God and heaven,” Columban taught. “Everything that we have or do should help us to become more like Jesus.” Columban was convinced of the truth of his words. It had been a challenge his whole life to keep thinking and acting always more like Jesus. And with his stubbornness and hot temper, it hadn’t always been easy!

As abbot, Columban was the spiritual father of all the monks. He corrected them when necessary, just as a good father does. He watched over their spiritual life and their physical health. Above all, he grew to love them very deeply as his brothers in Christ.

About twenty years after Father Columban’s arrival in Gaul, he got himself into deep trouble. Until that time, he had been friendly with the kings of Burgundy, even with those who were leading evil lives. Columban had often urged the young King Theodoric to change his sinful ways.

Then one day Columban paid a visit to Queen Brunhilda, Theodoric’s grandmother. The two had always been on good terms. But this time Columban said something in his usual honest way that offended Brunhilda deeply. After the abbot left, the queen began to urge the king and the local bishop to drive Columban and his monks out of Gaul!

Not long after that, Theodoric rode to Columban’s monastery with a band of soldiers. He had the abbot seized and taken to Besancon, a city forty miles to the south. He permitted only one monk to go with Columban. Although Columban and his companion could to walk freely around the city, the bridge and road leading back to Luxeuil were always guarded.

Then, one Sunday morning, Columban looked out over the river and saw no guards on the bridge. He and his companion quickly set out for home.

Hardly had Father Columban returned to Luxeuil when a band of horsemen thundered up to the monastery gates. They had come for him again. The soldiers searched the monastery, but all the monks looked alike to them. Only the captain recognized Columban, who was sitting by the church door reading a book as if nothing were happening. The captain pretended not to see him. “Let’s go,” he told his men. “This man is hidden by divine power.”

The soldiers got back on their horses and rode off.

A few days later, while they were singing the psalms, Columban and his monks once more heard the clattering of horses’ hooves and the clash of steel weapons. Soldiers poured into the church. “Man of God,” called one of them, “we beg you to obey the king’s command. Leave this land and go back where you came from.”

Columban replied slowly, “I don’t think it would please the Creator if a man were to return to his homeland once he has left it for the love of Christ.”

The soldiers understood. But they knew that Theodoric could have them killed if they didn’t obey his orders. “Father, take pity on us,” they begged. “We don’t want to take you away by force, but if you don’t leave Luxeuil, we’ll all die!”

Columban was moved with compassion. Turning to his monks, he said, “I’ll go with them.” He began to walk out of the church, then suddenly stopped and prayed, “O eternal Creator, prepare a place where we, your people, may serve you forever.” The monks gathered about him. “Don’t lose hope,” Columban quietly told them. “Continue to sing the praises of almighty God. The sacrifice we’re making will be rewarded by many more young men coming to join us.” He paused. “If any of you wish to come with me, you may.”

An uproar followed. All the monks wanted to come!

“No,” replied the soldiers. “The king has ordered that only the monks from Ireland and Brittany may accompany the abbot.”

And so Columban left his beloved Luxeuil with only a few of his monks. The soldiers went with them all the way down to the River Loire, where they all boarded a small boat bound toward the sea. It was, in all, a journey of about 600 miles. In the cities where they stopped, many people came out to greet the monks because they had heard about their holiness. Finally the little group reached Nantes, the port from which they were to sail for Ireland.

Columban sat down and wrote a long, anxious letter to his community at Luxeuil and their new abbot. He urged them to preserve their unity of spirit and their love for one another. He reminded the monks that their own sufferings were a share in the passion of Christ.

Confident that they had accomplished their mission, Columban’s guards had left him. They weren’t there to witness the fierce storm that blew up and caught the little ship just before it was to set sail for Ireland. The winds were so strong that the ship was lifted right out of the water and set down on dry ground! The superstitious captain and crew unloaded the monks and their baggage at once, and immediately the winds died down. The next day the ship sailed away—without Columban and his men!

To Columban, this was a sign that God didn’t want him to return to Ireland. Almost at once he and his monks were on the road again, heading northeast toward the safety of the kingdom of Theodoric’s brother—and enemy—Theodebert. They moved quickly and secretly. It was a tiring march of hundreds of miles over rough roads.

In Metz, King Theodebert welcomed Columban kindly. He was only too happy to help the monks whom his brother had exiled. He offered them land on which to build a new monastery.

“Since I’ve decided to journey to Italy, Your Majesty,” replied Columban, “I’ll look for a suitable place along the route and build there.”

After settling down in two different locations and being sent away twice by the non-Christian people of the area, Columban and most of his monks finally moved on to Italy. There, in the city of Bobbio, Columban built his last monastery on land given him by the Lombard king of northern Italy.

Columban had no way of knowing that the monastery of Bobbio would become one of the greatest cultural centers of Europe, preserving for future generations the treasures of the Italian and Irish civilizations. He didn’t know that within fifty years his few monasteries would have multiplied into almost a hundred, and that many bishops would receive their early training within those walls. What Columban did know was that it was time to meet the Lord whom he had served faithfully for so long. One chilly November day, supported by the prayers of his monks, he peacefully went to his true homeland—heaven.

Sometimes we’re faced with a choice between something we know we should do and something we’d like to do. When that happens, let’s remember St. Columban and the many sacrifices he made in his life. Let’s ask God to give us the courage to do what’s right, no matter the cost.