(1873–1897)

October 1

Thérèse Martin, born in Alençon, France, on January 2, 1873, was the youngest in a family of five girls. Zelie Martin, her mother, died of cancer when Thérèse was only four years old. To be closer to their mother’s family, the Martins moved to the town of Lisieux soon after Zelie’s death. Little Thérèse was raised by her older sisters, Pauline and Marie.

One day, Pauline showed Thérèse how all the people in heaven are completely happy even though some have more glory than others. She did this by taking a cup and a thimble and filling each with water. “Now,” she asked, “which is the fullest?” Thérèse was puzzled, for neither of them could have held another drop. “That’s how it will be in heaven,” Pauline said. “Every soul will be completely filled with happiness, but some will have more room for it, because they had a greater love of God when they lived on earth.” Then and there, little Thérèse decided to let herself be filled with a great love of God.

Pauline also taught her younger sister all about the religious feasts. Thérèse’s favorite was Corpus Christi, when the Blessed Sacrament was carried in procession through the streets of the town. The children would spread flowers along the road in front of it. Thérèse thought that each flower was like a kiss to Jesus in the Eucharist.

When Thérèse was ten years old, her beloved sister Pauline left the family to become a Carmelite nun in the monastery at Lisieux. Carmelite nuns are cloistered, which means they spend all of their days, and part of their nights, too, in prayer and meditation, and they don’t leave their monastery. Thérèse was terribly upset that Pauline wouldn’t be at home with her any more, acting as her “second mother.” But Pauline explained, “Thérèse, the sisters at Carmel live for God alone. This is what I want to do with my whole heart. It will make me very happy.”

At that moment, Thérèse knew that she, too, wanted to live for God alone, and that someday she would enter religious life as a Carmelite.

The following year, on the day of her First Holy Communion, Thérèse told Jesus that she was entirely his. She was crying for joy. That day she listed her resolutions for progress: “I will never let myself become discouraged. I will say the Memorare daily. I will try to be humble.”

When the Holy Spirit came to her in Confirmation, Thérèse felt great joy. She understood that she was receiving strength for the spiritual battles that would come in her life.

Thérèse couldn’t bear the thought of anyone going to hell. She knew that Jesus wanted everyone to be happy with him forever in heaven. She prayed often for the conversion of those people who refused to love God and obey the commandments.

When Thérèse was fourteen, the newspapers were filled with reports about a murderer named Pranzini who was going to be executed but wouldn’t repent of his crime. This was her chance to pray for a particular sinner! “Dear God,” she prayed, “send Pranzini the grace of repentance, because of the merits of the passion of Jesus!” She prayed long and hard for that man, and offered sacrifices for his conversion. At the same time, she confided to Jesus: “He’s my first sinner, so please give me a sign that he’s been converted—any little sign.”

The day of the execution came. And what did the newspapers say about the criminal’s death? Just before he died, the murderer had asked for a priest, whom he had ignored until then. The priest held up a crucifix, and Pranzini kissed it three times. He was sorry for what he had done! Thérèse had her sign. She knew that her “first sinner” had been converted.

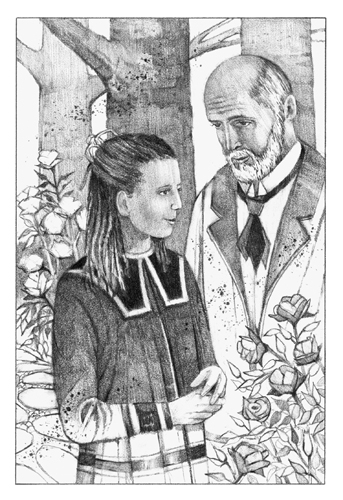

By this time, Marie had joined Pauline at the Carmelite monastery, and Thérèse’s sister Leonie had become a Poor Clare nun. Only Celine and Thérèse were left at home. Thérèse still wanted to enter Carmel. She wasn’t sure how she should tell her father, because he loved her very much. Now that he was growing old, he would feel so lonely without her! But Jesus was calling her, and she had to answer. Thérèse chose a beautiful spring evening, the feast of Pentecost 1887, to break the news to her father. “Papa,” she began as they walked together in the garden, “I want to enter Carmel.”

Mr. Martin had suspected that Thérèse wanted to give her life to God. Although it was a great sacrifice to let his daughters go, Mr. Martin felt privileged to have them serve God as sisters. But Thérèse was so young…only fourteen. With tears in his eyes, Mr. Martin hugged Thérèse after she told him how strong her desire was. “You have my permission,” he quietly told her.

But there was a problem. Thérèse’s uncle Isidore was her legal guardian, and he insisted that she was too young to enter such a strict Order. Thérèse cried, but then she prayed for a miracle—and waited.

Three painful days passed, and Thérèse went back to her uncle’s house. “Thérèse,” began Uncle Isidore, “I’ve been praying about your request—and God has let me know that it’s right for you to enter Carmel.” Thérèse had her miracle!

On a spring night when she and her father were walking together in the garden, Thérèse forced herself to speak.

Thérèse applied for admission to the convent. The nuns were willing to accept her, but Father Delatroette, the priest who supervised the monastery, wasn’t. “She’s too young for this demanding way of life,” he insisted. “She can’t be accepted until she’s twenty-one!” Not ready to give up, Thérèse appealed to the bishop. But he didn’t want to make a decision until he had discussed the matter with Father Delatroette. Thérèse left the bishop’s house in tears.

Three days after the visit to the bishop, Mr. Martin, Celine, and Thérèse set out for Rome with a pilgrimage group from their diocese. Thérèse planned to bring her case to the Holy Father. After all, if he said that she could enter the monastery, everyone else would have to agree! On the way, the pilgrims visited many beautiful and holy places, including the House of Loreto, where, according to legend, the Holy Family had lived when at Nazareth, and which had been carried to Loretto, Italy, by angels hundreds of years before.

The pilgrims finally reached Rome, and the day for their audience with the Pope arrived. Everyone was told not to speak to the Holy Father. But Thérèse had to! So when her turn came to kneel and kiss his ring, she bravely asked, “Holy Father, in honor of your jubilee, allow me to enter Carmel at fifteen.” Pope Leo XIII bent toward her and kindly replied, “You will enter if it is God’s will.” Then two papal guards lifted Thérèse to her feet and led her away.

Poor Thérèse! It seemed that the journey had been in vain! She, Celine, and their father were very sad as they began their return trip to France. But Thérèse kept on praying. About a month after she returned home, the bishop unexpectedly agreed to let her enter the Carmelite monastery after Lent the following year!

Thérèse entered Carmel on April 9, 1888, which was the feast of the Annunciation that year. She began her religious life by offering her prayers, works, and sacrifices especially for priests. When the time came to receive her religious name, she received the name Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus of the Holy Face.

Thérèse had a strong desire to become a saint, and she asked God’s help to do each duty in the best way possible out of love for him. Her famous “little way” to God was made up of prayer, humility, and love. Thérèse was convinced that anyone could become holy by simply loving God and doing even the smallest action well for the love of God. Whether it was time to sweep the hall, pray, or help care for a sick sister, Thérèse did it as if it were the most important thing in the world.

Thinking of this “little way” of holiness helped Thérèse to give an extra bright smile to the sister who annoyed her the most. When someone didn’t approve of the way Thérèse did something, she would do it all over again in the way the other person suggested. She accepted the cold in the winter and the heat in the summer without complaining. Sometimes it was difficult, because her cell was terribly cold in wintertime, and often she hardly slept at all. But she never let the other sisters know about it, and she tried to be as cheerful and full of energy in the daytime as she would have been after a full night’s rest.

One Christmas, Thérèse’s sister Pauline, who was now the prioress of the monastery, asked Thérèse if she would write down the story of her life. Thérèse was surprised. She couldn’t imagine why anyone would be interested! But she did as she was asked. She called her autobiography The Story of a Soul. Thérèse also wrote poetry and prayers.

Sister Thérèse was developing a troublesome cough. Eventually she became very sick, and started to cough up blood. She became weaker and weaker. When the doctor was called in, there was nothing he could do to save her. She had a very painful, fatal form of tuberculosis.

Thérèse’s final days were filled with almost unbearable pain. Thérèse knew she wasn’t suffering by herself. She felt herself united to Jesus on the cross. Like Jesus, she offered all her pain to God in reparation for sin, and so that sinners would repent and return to God’s love. She also prayed in a special way for priests and missionaries, that they would always know how much love God has for them. She was only twenty-four years old when she died in 1897.

A year after her death, the bishop gave permission to publish Thérèse’s autobiography, The Story of a Soul. Soon the book had been translated into thirty-five languages! People all over the world have learned about her “little way.” In 1925, Thérèse was declared a saint. In 1997, a hundred years after her death, Pope John Paul II named her a “Doctor of the Church,” which means that her writings have helped people everywhere to learn about what we believe and how we live as Catholics.

To St. Thérèse, “little things” were what mattered. She never did anything special or outstanding, but she did everything with great love. Thérèse shows us that love is what brings us very close to God.