Chapter 6

There was an ant named Jerry Peters who lived in a big ant hill near the henhouse. Ants are worthy citizens, but they are not, as a rule, very much fun. They work hard from dawn to dusk seven days a week without even stopping for lunch, and they despise all creatures who do not work as hard as they do. Since there are no animals or insects that work as hard as they do, they despise nearly everybody. And as for games and jokes, I don’t suppose there is a man living who has ever seen an ant laugh.

But this Jerry Peters was different. On warm sunny days you would often find him lolling comfortably under the shade of a dandelion leaf, leaning back with his feelers clasped behind his head and his six legs crossed, and the little brown beetle which he kept as a pet, crouched at his feet. The beetle’s name was Fido, and he was devoted to his master. He was not much bigger than the head of a pin, but his heart belonged to Jerry.

Or sometimes Jerry would go off, with Fido at his heels, for a long aimless ramble about the farm. The other ants could not see that he brought back anything of practical value from these excursions, since to them the discovery of something new and different which could not be eaten, or an interesting exchange of experience with a chance-met grasshopper, was a complete waste of time. But though they considered him a loafer, they never argued with him, for argument too was a waste of time. And if they pushed him contemptuously aside when he got in the way, Jerry didn’t mind. He just went and took a nap somewhere else.

But Jerry was no fool. The summer before, in the course of his explorations, he had wandered into the pigpen, and had been very curious about the papers and books on Freddy’s desk. He had hidden in a crack and watched for a week. He had seen Freddy typewriting, and then heard him read over what was written, and then he had put two and two together and one day came up over the edge of the page and waved his feelers.

“Hey!” said Freddy. “Go away, ant, I’m busy. I … What is it?” he said, as Jerry continued to wave. “You want something? O. K. let’s have it.” And he put his ear down as close as he could get it. But all he could hear was a faint whispering.

“Sorry,” he said. “Your voice is too small. Wait a minute, though! We need a megaphone.” He took a sheet of paper and rolled it into a cone. Then he put the small end close to the ant and put the big end at his ear. And Jerry’s voice came quite clearly. “I want to learn to read,” he said.

“You want—what?” said Freddy. “Learn to read? What on earth for?”

“So I can read, stupid,” said Jerry. “What else would I want to learn for?”

“H’m,” said Freddy; “well, I suppose that is a good reason. But—”

“Now don’t give me a lot of stuff about what use will it be for me,” interrupted Jerry. “Because I like things that aren’t any use to me. Such as watching the clouds on a summer day, or taking walks to nowhere in particular, or listening to the wind in the grass. And as far as I can see, reading is just another of those things.”

“Not at all,” said Freddy rather stiffly. “Reading is the—h’m, the gateway to knowledge. It opens up the—ha, the portals of wisdom. It permits you to share the thoughts of all great thinkers of the past—”

“Such as what?” said the ant.

“Eh?” said Freddy.

“What thoughts?” said Jerry. “What are some of these great thoughts? You read a lot. Give me just one great thought you’ve got out of your reading.”

“Well, naturally,” said Freddy, “you can’t just offhand pick out one. There’s Shakespeare, for instance, whose Complete-Works-in-One-Volume I possess. Shakespeare is full of great thoughts—”

“Such as?” said the ant.

“See here,” said Freddy, “you—whatever your name is—I’m not going to be cross-examined by an ant. You say you want to learn to read. Very good, very praiseworthy. But you can’t ex pect me to give you the results of my wide reading in two minutes. If you want to know these things, learn to read and then read them for yourself.”

“That’s just what I want to do,” said Jerry. “Look, I didn’t mean to be fresh. I’ve just got the idea from watching you that reading was fun, and I thought I’d like it. I don’t want to work. I don’t like work. And what’s more, I don’t see that it gets you anything, either. Look at my family. Work, work, work—and what has it ever got them? Just more work, that’s all. Well, what fun is there in that?”

“None,” said Freddy. “I quite agree with you. And yet, there’s something wrong about your argument, too. For instance, I write poetry.” He paused a moment for Jerry to express gratification at meeting so distinguished a pig, but as the ant didn’t say anything, he went on. “Now that is work, and pretty hard work, too. And yet it’s fun. Eh? How about that?”

Freddy always liked this kind of argument, and could go on for hours without ever getting anywhere. Which was an advantage in a way, because if it had ever got anywhere it would have to stop. But in Jerry he had met someone who was just as good as he was.

“You say your work is fun,” said the ant. “But if it’s fun then it can’t be work. It can’t be both.”

Well, the argument went on for a long time, but I don’t know that we need to follow it any further. In the end, Freddy agreed to teach Jerry to read, and the lessons began that day. Freddy had taught most of the Bean animals, and was a pretty good teacher, and Jerry could learn when he put his mind to it, and whether it was work or fun, by the end of the summer he could read almost anything. Freddy would open a book and Jerry would walk along the line of print. When he came to a word he didn’t understand, Freddy would tell him what it meant, and Jerry would go on. Often Freddy would leave a book or a magazine open on the desk, when he was going out, and Jerry would read along until he got to a word he didn’t know, and then he would just lie down on it and go to sleep till Freddy came back. Or if he wasn’t very sleepy, he would try to teach Fido to read. But it wasn’t much use. I guess anybody as small as Fido is too small to be a very good student.

Freddy got very fond of Jerry Peters. They spent hours arguing about nothing much, and talking about nothing in particular. Freddy made a big funnel out of brown paper and hung it up on the wall, and when they wanted to talk, Jerry would go down into the little end of the funnel and then his voice would come out almost as loud as Freddy’s. And at last, along in the fall, Jerry asked if he and Fido couldn’t come and live in the pigpen that winter.

“You see,” he said, “in winter the ants all stay underground. It’s dark and gloomy, and there’s nothing to read, and there’s a kind of general atmosphere at work that’s very depressing. We wouldn’t take up much room. And of course we wouldn’t expect you to entertain us or anything; you’d just go your way and we’d go ours.”

Freddy’s experience with guests had been that they expected to be entertained a lot, and that when they weren’t being entertained, they expected you to be feeding them. But Jerry didn’t care about parties, and feeding him was no problem, for one gumdrop would keep him going for six months. As for Fido, I guess food rationing wouldn’t have bothered him much either, for it would probably have taken him his entire lifetime to work through a jelly bean. As it turned out, they both lived very well on the crumbs they found in Freddy’s old armchair, which of course had never had a cleaning since Freddy got it. In fact, Jerry said afterwards that he had never had such a variety of good meals before, for there were crumbs of all sorts of cookies and cake, and bits of pie and candy.… He said if the other ants found out about it they would certainly leave their hill and move into the armchair. Freddy said it made him itch just to think of it.

Of course Jerry had to stay indoors all winter, but as soon as spring came and it began to get warm, he was anxious to get out. It was still too wet underfoot for an ant to go anywhere, so Freddy took him. He rode on the tip of Freddy’s ear, and when he wanted to say anything, he would shout it down the ear, and then Freddy would answer him. At first it seemed pretty funny to the other animals to see Freddy walking around, apparently talking to himself, and some of his friends thought he was getting queer and began worrying about him. And as often happens in such cases, they were so worried that they just talked among themselves about it and didn’t say anything to Freddy.

One morning—it was the day after the second issue of the Bean Home News came out—Freddy and Jerry were coming down past the back porch of the farmhouse, busily discussing an idea Freddy was working out for his paper. Freddy thought he would take some of the old familiar poems, and rewrite them for animals. He had started to rewrite one:

Breathes there a pig with soul so dead

Who never to himself hath said:

“This is my own, my native pen?”

Whose heart has ne’er within him burned

As home his trotters he has turned

From wandering in the world of men?

Jerry didn’t like the idea. He thought Freddy ought to write original poems, his own poems,—not try to fix up something that had been written by someone else. He thought Freddy’s poems were much finer than those he wanted to rewrite.

“Nonsense!” said Freddy modestly. “That poem is by Sir Walter Scott. I may be good, but I’m not as good as Scott and Longfellow and Shakespeare. No, no, my dear fellow,” he said, “you have much too high an opinion of my feeble verses.”

“Oh, I wouldn’t say that, pig,” said a sarcastic voice. “What’s Shakespeare got that you haven’t got, hey?”

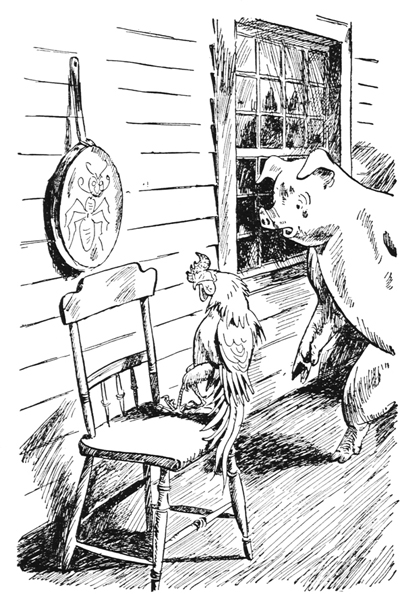

Freddy turned sharply. Neither he nor Jerry had noticed Charles, who was standing on the porch. He spent most of his time there nowadays, admiring himself, when he thought nobody was looking, in the shiny bottom of the iron frying pan.

“Can’t you get anybody else to tell you how smart you are, that you have to walk along, telling it to yourself?” continued Charles.

Freddy laughed. “I don’t know that it’s any worse than your telling your reflection in a mirror how handsome you are all day long.”

“Oh, is that so!” said Charles. “Well, I guess if you’d look in a mirror once in a while, you wouldn’t always be going around shaking hands with yourself. I guess you wouldn’t be so pleased with what a pig looks like.”

“What’s all the row?” asked Jinx, coming out from under the porch where he had been annoying a beetle. “Great Scott, Charley, are you still up there making noble faces at yourself? You know, Freddy, we’ve got to do something about Charles. He’s falling in love with himself. He does nothing but strut up and down in front of this frying pan all day long, looking magnificent.”

“I do not!” said Charles. “I come to look at myself in it once in a while—sure, I do. I’m not like some of you animals that don’t care how they look. Mr. Bean expects us to look nice, and how can you tell if everything is all right unless you take a look at yourself once in a while?”

“That’s all right,” said Freddy, “but you’ve been looking at yourself for two weeks, and if you can’t tell what’s wrong in that time, you’d better give up.”

“You’d better ask me,” said Jinx. “I can tell you what’s wrong in two seconds.”

“Aw, you make me sick,” said Charles, and walked to the other end of the porch and turned his back.

Freddy and Jerry went down to the bank to see if Ernest, Jr. was awake, and then they went home.

“I suppose it is a good thing to know what you look like,” said Jerry. “You know, Freddy, I’ve never seen myself.”

“You look just like other ants,” said Freddy.

“You don’t look like other pigs,” said Jerry.

“That doesn’t sound like a compliment,” said Freddy. “Well, let’s see.” He looked at a small mirror which hung on the wall, but, like his window panes, it hadn’t been cleaned in several years, and all he could see in it was just sort of a faint shadow of a pig. He wiped a cloth across it, but that only made it worse. What he saw then was the shadow of a pig with zebra stripes and one black eye. “I guess you couldn’t get much idea what you look like from that,” he said. “Maybe I could draw your picture. I’m pretty good with a pencil. Only your face is so small. I don’t think I know really what you look like myself.”

He rummaged around in the drawer of his desk and brought out a large magnifying glass. Then Jerry got down on a sheet of white paper and Freddy held the magnifying glass over him—and gave a loud cry of dismay. “Good gracious, Jerry, you’ve got an awfully ferocious looking face!”

“Have I?” said Jerry in a pleased voice. “I wish I was bigger. Maybe I could scare people. I never can scare anybody—even Fido. Where is Fido, anyway? Didn’t he go with us? Here, Fido! Fid—oh, there you are, you bad beetle! Hiding behind me like that!”

Fido rolled over on his back to show he was sorry and waved all six legs in the air, and Jerry patted him with his feeler and told him to lie down and keep quiet. For Freddy had begun to draw.

Freddy erased a good deal when he drew, and on the difficult parts it seemed to help him to stick his tongue out and move it around as if he was drawing with it and not with his pencil. He was fond of Jerry and wanted to give him a pleasant expression, but the harder he worked the more terrifying the portrait looked. Ants haven’t much expression anyway, except a sort of dragon-like ferocity. They don’t mean anything by it; it’s just the way their faces are put together.

“Well,” said Freddy at last, “I guess this is the best I can do.” And he held the drawing up for Jerry to see.

The ant looked at it for a long time, then he climbed up on Freddy’s ear. “Do I really look like that?” he said. “Golly, I’d hate to meet myself on a dark night.”

“Well, as Mrs. Bean says, you’ll never be hung for your good looks,” said Freddy. “But for that matter, neither will I. If the Bean farm ever has a beauty show, you and I had better be the judges.”

“Yes, I know, Freddy,” said the ant, “but you’re nice looking. You’re not handsome, but you look pleasant. But I look—well, I wonder how Fido stands it.” Then he laughed. “Though I will say that when I was looking up at you through that magnifying glass, you were pretty scary yourself.”

“Say, I’ve got an idea,” said Freddy. He took the drawing and some colored crayons and went out and across the barnyard to the back porch, where Charles was still strutting up and down.

“Hey, Charles,” he said, “Henrietta wants you.” And as soon as the rooster had hurried off he took his crayons and copied his picture of Jerry’s face on the bottom of the frying pan. Then he sat down and waited.

He had barely finished when Charles came running back. “Say, what’s the idea?” he demanded. “Henrietta didn’t want me.”

“Of course she didn’t,” said Freddy. “I just wanted to pry you loose from that frying pan for a few minutes. What you said a while ago about how we ought to try to look our best—well, I guess I’ve been kind of careless of my appearance and I thought I’d take a look at myself and see if anything needed to be done.”

“There’s plenty to be done, all right,” said Charles, looking at him scornfully. “But if you can do it to that face, you’re a wonder.”

“You don’t have to be unpleasant about it,” said Freddy humbly. “I know I’m not as handsome as you are. You’ve got a fine, noble profile, Charles—there’s something of the eagle in it, proud and haughty, but with more dash, somehow, than an eagle. No, I wouldn’t kid you; take a look in the frying pan yourself.”

Charles was suspicious, but he could not resist a quick glance, for Freddy had edged him around until he was directly in front of the frying pan. He looked, then his head darted forward and he stared. And then he gave a faint gurgle and fell over in a dead faint.

And then—he fell over in a dead faint.

“Golly,” said Freddy. “I didn’t think he’d take it that hard!” He called Jinx out from under the porch, and they were working over Charles to bring him around, when a big car drove into the barnyard. “Wow!” said Freddy. “Mrs. Underdunk!” And he dove off the porch into the bushes.

The chauffeur held the door open, and Mrs. Underdunk got out just as Mrs. Bean came to the door to see who her visitor was.

“How do you do,” said Mrs. Bean pleasantly.

Mrs. Underdunk did not reply. She looked Mrs. Bean up and down through a little pair of glasses which she held up to her eyes on a stick. “I am Mrs. Humphrey Underdunk,” she said. “I understand you are the owner of a pig.”

“Why, yes,” said Mrs. Bean. “Won’t you come in?”

Mrs. Underdunk came up on the porch. “I can say what I have to say here,” she said. “I wish merely to warn you that you will have to keep your pig tied up. He has been running wild and causing disturbances in Centerboro. We are not going to allow that.”

“Why, dear me,” said Mrs. Bean. “Do you mean our Freddy? Freddy wouldn’t cause disturbances.”

“The fact remains that he did,” said Mrs. Underdunk. “If he is found in the village again, I have given orders—”

“Excuse me, ma’am,” said Mr. Bean, appearing beside Mrs. Bean in the doorway, “but who are you to give orders about my pig?”

“I have given orders,” said Mrs. Underdunk calmly, “that he is to be shot.”

Freddy, peering out through the bushes, couldn’t tell whether Mr. Bean was angry or whether he was smiling. Or maybe both. Behind all those whiskers, you couldn’t tell much more about his expression than you could about an ant’s, Freddy thought.

“So he’s to be shot,” said Mr. Bean. “Well, now I’ll give some orders. I’ll order you, ma’am, to kindly get in your car and drive back home. If my pig has trespassed on your land or uprooted your garden, you can go to law about it. You can make me pay for any damage he’s done. Bring your proofs into court, ma’am, and I’ll meet you there. But don’t come out here with threats about shooting my pig.”

Mrs. Underdunk glared at him and pressed her lips tight together. “Very well, then,” she said. “If you choose to be stubborn about it, you’ll have only yourself to blame. I warn you again: if that pig is allowed to run wild, he—will—be shot!” She emphasized each word with a nod of her head, and on the last nod her hat slipped down over her nose. As she turned to go, she stooped to straighten her hat in the shiny bottom of the frying pan, which had caught her eye. She had put her hands up to her head; they stayed there a moment, poised; then they dropped slowly, and with a gurgle which was exactly like the one Charles had given, she fainted away.

“Boy!” said Freddy in an awed tone. “Am I a good artist!” And while the Beans were sprinkling water on Mrs. Underdunk and slapping her hands to bring her to, he quickly erased the picture from the bottom of the frying pan.