Chapter 8

In the next issue of the Bean Home News Freddy printed the whole story of his disagreement with Mrs. Humphrey Underdunk, as the sheriff had suggested. He also printed a spirited defense of the sheriff, and of the management of the jail. The result was better than he had hoped. A hundred and fifty of the Centerboro people subscribed to the paper the following day, and for a week it was the talk of the town.

But the sheriff pointed out to Freddy that he mustn’t count too much on that. “Lots of people don’t like Mrs. Underdunk,” he said, “but not likin’ her and not doin’ what she wants ’em to are different. You can get ’em to agree that’s she’s mean and unfair, but they’ll keep right on doin’ what she asks ’em to because they’re afraid of her. Take Henry Weezer, president of the bank. He don’t like her a little bit. But she has a big account at his bank, and he’ll try to please her so she’ll keep her money there. Same with Lieber & Wingus at the hardware store, and Harry Ketcham at the grocery, and Dr. Winterpool. They don’t want to lose her trade.”

“You mean you don’t think it did any good?” asked Freddy.

“I don’t mean that at all,” said the sheriff. “You gave ’em your side of it, and it’s funny, Freddy, but they believe you instead of her. I don’t mean it’s funny to laugh, I mean it’s funny-queer. And maybe not so queer, either. Because they like you, and you’d always rather believe people you like. No, you keep right on. And thanks for that piece about me. The boys at the jail have had it framed and hung up in the music room.”

The Guardian came right back the following week with another attack on the sheriff, criticizing his management of the jail, and also his failure to enforce the laws against animals which ran wild and made nuisances of themselves. “Not only are we continually subjected to the attacks of wild pigs,” Mr. Garble wrote, “but recently our nights have been made hideous by a plague of howling cats. We have frequently taken occasion to suggest that a sheriff whose bosom friends are pigs and other of the lower animals is a disgrace to a thriving town like Centerboro, the garden spot of Oneida County. But are we to have no protection, Mr. Sheriff, from these animal friends of yours? Beware, Mr. Sheriff! If such conditions are permitted to continue, an enraged citizenry will some day rise and drive you and your four-footed accomplices from the sacred soil of our community.”

At a meeting in the barn when these developments were discussed, Jinx said that he guessed they’d better not make any more midnight trips into town for scrap. “We’ve skimmed off the cream, anyway,” he said. “Five trips, and more than half a ton of stuff we’ve brought in. Guess we’ll have to think of something else. Gosh, I wish we could get that iron deer Mrs. Underdunk has on her lawn. It must weigh an awful lot.”

“She and her brother hate animals so much,” said Robert, “I’m surprised she’d even have an iron animal on her lawn.”

“She’s an iron woman,” said Freddy, and Mrs. Wiggins said: “My land, what does that Garble man mean, talking about that nice sheriff being a disgrace because he’s friends with animals? Lower animals, indeed! I’ll lower him if he ever comes around here!”

“I think,” said Jinx slowly, “that I’m going to have me some fun with Mr. Herbert Garble. I think some of these dark nights I’m going to pay him a little call.”

“You’d better lay off him, cat,” said Freddy. “Keep this a newspaper fight. We’re ahead now, and so long as we can fight him with printed words we’ll stay ahead, because we’re smarter than he is. But once we get down to a real rough-house—”

“I completely disagree,” said Charles in a loud voice. He hopped up on the dashboard of the phaeton. “My friends, lower animals all,” he said, “you will agree, I think, that we have been grossly insulted. My friend, Freddy, counsels us to reply to these insults—but with what? With blows? No, with further insults. As an editor, as a master of insult and invective, I respect his advice. But I, as a rooster, as a bird of spirit, beneath whose feathered bosom beats the stout heart of a long line of warriors—I reject his counsel. For my friends, it is a counsel of appeasement. No, no—rather let us perish nobly on a stricken field, than sit back and reply to these foul insinuations only with words. Let us strike! Who will follow me?” And he jumped down and strutted towards the door.

There was some applause, but it was rather for the fine words than for the sentiments expressed.

“Where do you want us to follow you to?” said Jinx, and Freddy said: “Come back here, Charles. We can’t tackle Mr. Garble, and you know it.”

Charles turned upon them contemptuously. “Cowards!” he exclaimed witheringly. “Very well then, I will go alone,” and he left the barn.

“Hey, come back here!” shouted Freddy, but Jinx said: “Oh, let him go. He won’t get any further than the henhouse.”

“I’m not so sure,” said the pig. “Ever since he licked that rat in fair fight, he’s had these spells of thinking he can lick the whole world. And another thing; he thinks he’s pretty ferocious looking ever since he saw the ant’s picture in the bottom of the frying pan. He thinks he can scare Mr. Garble. I wish Henrietta was here. He may do something foolish.”

Unfortunately Henrietta had gone over to the Schermerhorn farm to see her married daughter that afternoon, and before they could think of any way to stop him, Charles was nearly out of sight down the Centerboro road.

What happened the animals later learned from Jinx, who was chosen to follow the rooster and see that he came to no harm. Charles, still inspired by his own warlike words, trotted along steadily, up hill and down dale, until he reached town. He perched for a few minutes on the watering trough in front of the bank to get his breath and arrange his feathers, and then he walked straight up the stairs to the Guardian office, and tapped on the door with his beak.

“Come in!” shouted an irritable voice, but of course Charles couldn’t open the door, so he tapped again.

There was the grate of a chair being pushed back and then the door was flung open.

“Well, who—” said Mr. Garble, looking around; then he glanced down. “Great jumping peacocks, a chicken!” he exclaimed. “Shoo! Scat! Get out of here!”

He made shooing motions with his hands, but Charles slid past him into the office and perched on the desk. Jinx said afterwards that he thought Charles’s nerve was just about to give out, and that in another moment he would have turned and flown squawking down the stairs. But the word “chicken” was a fighting word with the rooster. Like most big talkers, he usually backed down more or less gracefully before the first blow. But the word “chicken” made him see red.

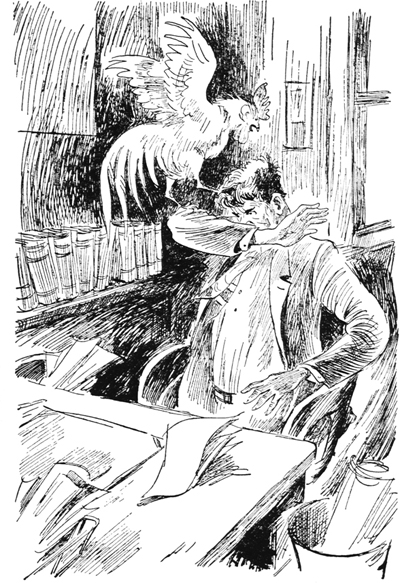

“‘Chicken,’ is it?” he squawked. “I’ll show you who’s a chicken.” And he flew at Mr. Garble, who was reaching for his ruler, and pecked him sharply on the hand, so that the editor dropped the ruler with a yell and put his finger in his mouth. And while he was sucking his finger, Charles went for him again. Jinx said Mr. Garble never had a chance. With one arm across his face, to protect his eyes, he stumbled about the office, reaching for something to strike the rooster with. But Charles’s claws were in his hair, and Charles’s wings beat across his eyes and blinded him, and Charles’s sharp beak was pinching his ears and his nose till he yelled with pain. “Chicken, hey?” Charles yelled. “Lower animals, hey? I’ll teach you to call respectable people names in your paper. I’ll give you a lesson you won’t forget!” And he seized Mr. Garble’s nose, which was large and so offered an excellent hold, and gave it a half twist. And yelling for help, Mr. Garble blundered out of the office and went stumbling down stairs.

Jinx said Mr. Garble never had a chance.

Charles would have followed, but Jinx caught him by the wing. “Hold it, old boy,” he said. “You’ve won. But don’t go out in the street, or he’ll get you. Out the window, now, quick, before he comes back with a gun. I’ll meet you on the edge of town.”

Charles leaned against the desk panting. “Why … I did win, Jinx!” he exclaimed. Then a look of horror came over his face. “Good gracious, what will Henrietta say? What on earth got into me?”

“One of your brave fits, I guess,” said the cat. “But come on, get going. Great Scott, don’t faint away now!” he said, as the rooster began to tremble at the thought of the danger that he had faced. “Come on, will you?”

“Golly, yes,” said Charles, and hopped up on the windowsill and fluttered down into the back yard.

They got away safely after that. Charles was a good deal worried on the way home about what Henrietta would think. But as frequently happens in such cases, Henrietta, when she learned of it, was pretty proud of him. Of course she gave him a good scolding, but Charles wasn’t upset about that, because she always scolded him three times a day whether he had done anything or not.