Chapter 15

The animals dragged the deer home right through the main street of Centerboro, and almost the whole town turned out to cheer and congratulate them. Weighing the deer when they finally got it home, was quite a job. They got it on one end of the plank all right, and then Mrs. Wurzburger and Mrs. Wogus got on the other end, and as many of the smaller animals as could stand under the cows got on, and at last Mr. Bean got up and sat on Mrs. Wiggins’ back. The deer began to go up off the ground, and then there was a sharp crack, the plank broke, and Mr. Bean and the animals went down into a struggling heap. The other animals sorted themselves out and got up slowly, but Mr. Bean and Mrs. Wiggins remained on the ground. They sat there and just looked at each other, and then the cow began to laugh.

When Mrs. Wiggins laughed you could hear her halfway to Centerboro. You’d have thought somebody was tickling a giant. And pretty soon Mr. Bean began to laugh too. They sat there just looking at each other and laughing, and the animals, who had never heard Mr. Bean laugh before, stared and stared. And then they began.

When Mrs. Wiggins had started laughing, Mrs. Bean hadn’t even looked up from her work in the kitchen, because she had heard that sound often enough. But when Mr. Bean started, it was a sound the like of which she had never heard before in her life, and she ran to the door.

“Good grief, Mr. B.,” she called, “what ails you? You sound like an old rusty gate.”

Mr. Bean stopped laughing and got up, and his expression might have been a little sheepish if anybody could have seen it.

“I was taking a cake out of the oven,” said Mrs. Bean, “and when you made that noise it just fell flat.”

“What’s the harm?” said Mr. Bean. “Cakes are better that way; got more body to ’em.”

Mrs. Bean smiled and went back in the house.

“Got to get the chores done,” said Mr. Bean, and went off to the barn. But every now and then as he worked he kept making strange fizzing noises in his beard, and the animals decided he was still laughing.

“Got started and can’t stop,” said Mrs. Wogus. “But how he holds it in, I can’t see. Land of love, if I tried to hold in when I wanted to laugh, I’d burst wide open.”

Two days later the heap of scrap iron was hauled away, and then the next day the sheriff came out and presented Mr. Bean with the pennant and the box of cigars. For the deer had won the prize for the Bean farm, whose pile was just ten pounds heavier than the next highest contestant, Zenas Witherspoon, whose farm was over the hill. Mr. Bean didn’t put the pennant on the house; he said the animals had won it, so he put up a little flagpole on the gable end of the barn, and the animals were pretty proud when they saw the blue pennant with its white S flying gaily in the breeze.

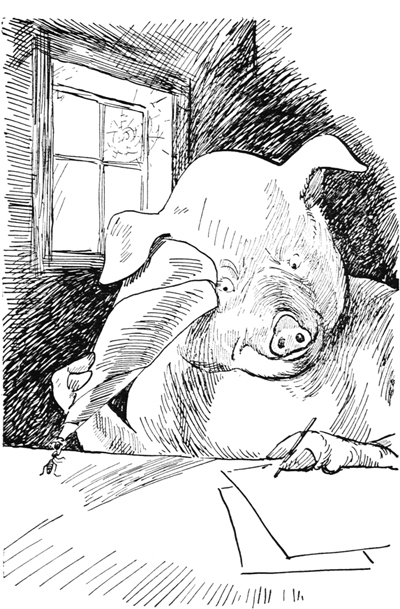

Late one afternoon Freddy was busy in his study. He was writing a poem for the Guardian & Bean Home News, and Jerry Peters was helping him. It went this way:

“Little sparrow, wren or crow,

Little singing vireo,

Little robin on a twig,

Don’t you wish you were a pig?

You can fly among the trees,

Chase the buzzing bumblebees;

You can swoop about the sky,

Very low or very high.

Such a life is very fine,

But it’s not as nice as mine.

Don’t you sometimes wish that you

Had four legs instead of two?

You have bugs and things to eat;

I am fed on proper meat.

You must live—”

“Hey, Freddy,” said Jerry, “don’t you ever write about anything but yourself?”

“H’m,” said Freddy. “I don’t know why it is that almost every poem I write, no matter what I start with, does seem to be mostly about me.”

“Well, I know,” said Jerry. “It’s because you’re stuck on yourself.”

“Well, I know,” said Jerry. “It’s because you’re stuck on yourself.”

“I don’t think that’s a very nice thing to say,” said Freddy. “I write about myself because—well, I know more about myself than anything else.” He thought a minute. “I’ll try another and keep myself out of it. Let’s see—

“Under the spreading maple tree

The Bean farm scrap pile stands.

Indeed, a mighty pile to see

Of wheels and frying pans,

Of stoves and horseshoes, nails and bolts,

Of springs and iron bands.

Week in, week out, from morn to night

You see the scrap pile grow.

One brings an iron bed, one a sledge,

One brings a rusty hoe.

And the pig, he weighs them carefully

When the evening sun is low.”

“There you are in it again,” said Jerry.

“Isn’t that funny!” said Freddy. “Let’s see …”

“The shades of night were falling fast

When up through Centerboro passed

A pig, who bore ’mid shouts and cheers,

A banner on which this appears: The Bean Home News.

“No, there I am again. Well, by gracious, I’m going to get one that I don’t come into.

“Oh, the bulldog on the bank,

And the bulfinch on the twig;

The bulldog called the bulfinch

A green old water—”

I guess it was a good thing that somebody called him at that minute, for he was certainly just about to come into that verse, too. He and Jerry went to the door of the pigpen to see a long black car drawn up in the barnyard, and Mrs. Bean talking to someone on the back porch. She beckoned to him, and he ran over, to find that the arrival was Mrs. Underdunk.

“Here is Freddy, Mrs. Underdunk,” said Mrs. Bean.

“Yes, I see,” said Mrs. Underdunk, and she looked at Freddy but didn’t say anything more. Mrs. Bean smiled at the pig and turned and went into the house.

“Don’t let her put anything over, now, Freddy,” Jerry cautioned him. The ant was sitting on the tip of the pig’s ear.

“You—you wanted to see me, ma’am?” asked Freddy.

“Yes. I have come to tell you that you need not be afraid that any member of my family will interfere with you again. I have learned what happened at the Cassoway farm. I find that I am indebted to you, since it was at your suggestion that my brother was not arrested. So you have nothing to fear from us in the future.”

“Why, thank you,” said Freddy. “That is very fair-minded of you.”

“No, it is not,” said Mrs. Underdunk stiffly. “I am not a fair-minded woman. It is simply that I dislike being indebted to a—to a pig.”

“I don’t think anybody likes being indebted to anybody else,” said Freddy. “But I still think you’re fair-minded. Because you just said you weren’t, and that shows that you are.”

“I have said that I’m not, and if that shows anything, it shows that I’m not,” said Mrs. Underdunk firmly. “Furthermore, I am not accustomed to having my statements questioned.”

“Oh, dear,” said Freddy; “I’m not questioning your statement, honestly. But look, Mrs. Underdunk. Some statements mean just the opposite of what they say. Suppose I say that I never tell the truth. Well, if that is true, then I always lie. But if I always lie, then I’m lying when I say I never tell the truth. So my statement really means that I am truthful.”

But Mrs. Underdunk was not entertained by this notion. “I daresay,” she said coldly. “However, it is not necessary to apologize to me for your untruthfulness.”

“You misunderstand me,” said Freddy. “I’m not apologizing for anything. I was just—oh, well, never mind.”

There seemed to be nothing further to say, but Mrs. Underdunk did not go. She appeared to have something on her mind. And finally she said: “I came out to see you today partly at Senator Blunder’s request. He is anxious to meet you, and—well, he has asked me to invite you to dinner. Tonight, if it is convenient.”

Freddy saw that she was greatly embarrassed at having to invite a pig to dinner, and he thought maybe he ought to be angry. But he was pretty kind-hearted, and when people were embarrassed he was always sorry for them, even if they were enemies. So he thanked her in a dignified way and said he was sorry he wouldn’t be able to come.

“The senator will be disappointed,” said Mrs. Underdunk, but she looked relieved.

“I don’t see why he wants to meet me,” said Freddy.

Mrs. Underdunk hesitated a moment, then she said: “Perhaps he had better tell you that.” She turned and beckoned towards her car, and the senator himself got out and came over to the porch.

“Ah, my young friend,” he said cordially. “A great pleasure to meet you. A great piece of work you did the other night, getting around our good friend Mrs. Underdunk and making her give up her iron deer.” He laughed a deep, well-oiled laugh. “Well, well, I am glad to see that there are no hard feelings between you. Everything all pleasant now, eh? And you’re coming to dinner, I hope? I think it will be to your advantage.”

“Well,” said Freddy, “I’m afraid—”

“Wait!” said the senator. “Don’t decide till you’ve heard more. You see, I am planning to run for governor next year, and I’d like to have you with me. I’d like the support of your newspaper, of course, but there’s more than that. You’ve the makings of a good politician. I could offer you a good position.”

“I couldn’t support you in the campaign,” said Freddy. “There won’t be any politics in my newspaper; Mr. Bean doesn’t approve of it.”

“It seems to me you have had nothing but politics in it,” said the senator. “No doubt that could be arranged. But I think very highly of your ability, and—well, I might as well tell you now—I might even consider you for a position on my staff.”

“My goodness!” said Freddy. He saw himself, sitting behind a large mahogany desk in the state capitol in Albany, pressing buttons for subordinates at whom he barked a string of crisp orders, and no nonsense, either! He would have a uniform—dignified, not too fancy; a blue uniform with epaulettes and a sword and a medal or two; with perhaps just a touch of red. Major Freddy, of the governor’s staff! And at banquets, he would sit at the governor’s right …

But this vision was interfered with by Jerry, who was pouring excited advice into Freddy’s ear. “The senator’s playing you for an easy mark. He just wants you to print nice things about him in your paper. You don’t think he’d really put a pig on his staff, do you?”

But Freddy didn’t stop to think whether he would or not. All his thoughts were taken up with the glittering picture of himself as Major Freddy. Perhaps even Colonel Freddy. Standing on a platform beside the governor, facing the cheering populace. He signaled with a wave of his trotter, and at once the massed bands crashed into the national anthem. And Brigadier General Freddy led the singing …

The senator, who had been waiting for his answer, smiled. “Well, well, I think we can come to an agreement.” And Mrs. Underdunk said: “We’ll expect you for dinner, then.” “We can talk over the staff appointment,” added the senator.

“For goodness’ sake, Freddy,” pleaded Jerry, “don’t accept. They’re just trying to make a fool of you.”

Freddy shook his head irritably. “I’m not as easy to make a fool of as all that,” he said crossly. “I wish you’d shut up and keep your long nose out of my affairs.” Unfortunately he forgot that the others could neither see nor hear Jerry, and he said it out loud.

Of course Jerry didn’t have a long nose, and for that matter, neither did Senator Blunder, but the senator very naturally thought Freddy was addressing him. “Well, of all the impertinence!” exclaimed Mrs. Underdunk. And the senator scowled. “Of course,” he said stiffly, “if you feel that way about it—”

It suddenly came to Freddy that he did feel that way about it. Jerry was right; they were trying to make a fool of him. “I’m sorry to have put it just that way,” he said, “for my remark wasn’t really intended for you. I thank you for your dinner invitation, but I really can’t accept. And as for the position on your staff—well, I have a position on Mr. Bean’s staff, and that’s all I want.”

Mrs. Underdunk was going down the steps, sputtering like a pack of firecrackers, and the senator followed her.

When the car had gone, Jinx came out from under the porch. “Well, pig,” he said, “you’re moving in high society these days, I must say. What’s the matter—you look as if you’d swallowed a moth ball.”

“I’ve just turned down a chance to be a brigadier general,” said Freddy.

“Pooh! Who wants to be a general? Generals can’t lie around in the shade all day, and write poetry, and take naps. Generals have to get up early in the morning—my goodness, they have to fight battles!”

“Well, I guess it wasn’t much of a chance anyway,” said Freddy. “I guess the senator just wanted me to print his speeches in the Bean Home News. And when it came to putting me on his staff, he’d have sneaked out of it. Even if he hadn’t, I’d have been sick of it in a week. I have a pretty nice life here on the farm. I wonder why I’m always wanting something different?”

Jinx, who didn’t enjoy discussing such questions, said he didn’t know and didn’t care. The two friends walked together up along the brook. They waved to Alice and Emma, who were doing their usual imitation of two powder puffs on the glassy surface of the duck pond, then found a cool fence corner under the shadow of the woods and stretched out in the long grass.

“Ah!” said Jinx, yawning luxuriously, “this is the life! Bet you don’t want anything different now.” And he began to purr.

“No,” said Freddy, “I don’t want a thing.” For a little while neither of them said anything. Then Jinx raised his head and looked curiously at the pig, who was making a sort of snoring noise. “For Pete’s sake, Freddy! I thought you’d gone to sleep, but your eyes are open. Do you have to make that racket?”

Freddy stopped it and sat up. “I was just thinking,” he said, “how nice it would be if I could purr like you do. It’s such a comfortable happy sound—”

“Well, that snorting you were doing isn’t very happy,” said the cat. “Sounds like somebody tearing up carpets.”

“I never tried it before,” said Freddy. “Maybe I need practice. Maybe you could give me purring lessons, Jinx. How about it?”

“Oh, for goodness’ sake!” said the cat exasperatedly. “Can’t you be quiet ten minutes? You just said you didn’t want anything different, and then you suddenly aren’t happy because you can’t purr. Now pipe down.”

So Freddy put his nose down and closed his eyes. But he went right on thinking. And half an hour later, when Jinx woke up from his nap, Freddy was gone. He was down at the duck pond, trying to get Emma to teach him how to quack.