18 Sensuous Memory, Materiality and History: Rethinking the ‘Rise of the Palaces’ on Bronze Age Crete

Abstract

The main thesis of this chapter is that sensuous, bodily memory and mnemonic history were fundamental in the constitution and materialisation of Bronze Age, or ‘Minoan’, Crete. By examining two contexts, the funerary arena of the Prepalatial period, and Palatial contexts at sites such as Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and Petras, it is argued that the interplay between remembering and forgetting, and the need to materialise ancestral, mnemonic links and associations, were responsible for many of the material and social practices witnessed by archaeologists. Furthermore, I maintain that remembering and forgetting – and the forging of mnemonic links – were played out in embodied ceremonies and rituals, in mortuary and other contexts, where commensality and drinking ceremonies in particular were central. The question of the ‘rise of the palaces’ is then revisited through this prism, and it is argued that a more fruitful explanation would be to see the phenomenon as the celebration, materialisation and glorification of indigenous, long-term history and memory, which took place in locales with a deep history, places that were special because of their ancestral, historical connotations, and their long-term association with rituals of commensality. Memory, however, has it own political economy, and this process of drawing on and materialising mnemonic links and associations was highly contested.

Introduction

An illustration in Renfrew’s influential and still valuable The Emergence of Civilisation is most telling with regard to the approach I take in this chapter: a Piet de Jong artistic image (after Evans) of a Late ‘Minoan bathroom’ from Knossos (Renfrew 1972: fig. 21.3). This is in fact the very last image in the book, located in the concluding chapter that deals with the ‘multiplier effect in action’: the assumed impact of processes such as Mediterranean ‘polyculture’ (following the introduction of grapevine and olives) and ‘redistribution’ in bringing about ‘civilisation’, which Renfrew equates with the development of ‘palaces’ in Bronze Age Crete. The message conveyed by this image is that only civilised society constructs lavish, elaborate baths. This recalls the popular fascination with the perceived sophistication of the Minoan sewage system, evoked by countless tourist guides to Cretan sites to the present day, but also the nineteenth-century advertising slogan by the Unilever company declaring that ‘soap is civilisation’ (McClintock 2000: 207).

It is this popular and academic notion of a developed, European, ‘civilised’ society which achieved olfactory neutrality (much like an early modernist world that ‘declared war on smells’; Bauman 1993: 24), and more broadly this modernist construction of a Bronze Age context, that I want to challenge here. Since its archaeological remake at the start of the twentieth century, this context has operated as the playground for all sorts of scholarly and popular fantasies: at times a peaceful ‘paradise lost’, a world of tolerance, sexual ambivalence and experimentation (e.g. papers in Hamilakis and Momigliano 2006, especially by Roessel); at other times and by other writers a highly organised ‘state’ society (or a proto-state, a segmentary state or a chiefdom, depending on the author), a ‘first level state civilisation’ with its clearly defined political-administrative territories and its hierarchical, multi-tier settlement pattern. We are thus left to choose between the western European escapist desire for a liberal, free-love utopia, and the neo-evolutionist fantasy and desire for order, hierarchy and administration. In this chapter, I attempt not so much to produce but rather evoke an alternative history of Bronze Age Crete, a history from below, one that puts at its centre sensorial experience and mnemonic recollection. Political economy and the dialectics of power are present throughout, but this is a political economy produced in the arena of sensory experience and sensuous memory.

Sensory and sensuous archaeologies are not representations of the past but rather evocations of its materiality and its affective impact. Evocation is not an easy task, especially through the medium of a chapter such as this one. While what follows is still a scholarly and academic account, it is also, at least in part, an experiment in sensuous archaeology. At certain moments, especially in the first part of this chapter, I attempt to combine academic essay and storytelling, sacrificing neither the rigour of scholarship involved in the former nor the immediacy and the evocative power of the latter (Jackson 1998). This study is not an attempt to write a rigid, chronologically complete and bounded, total and totalising history of Bronze Age Crete. Rather, it is an experiment in narrating a series of vignettes, fragments of material and sensuous lifeworlds, hopefully retaining and conveying the texture and carnality of intersubjective and inter-corporeal experience. The chronological framework for this enquiry is broad, ranging from the Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100/3000 BC) to the end of the ‘neopalatial’ periods (ca. 1500/1450 BC). Two main contexts are examined here: mortuary, and ‘palatial’.

The Smell of Death

If you come to my funeral, I will come to yours. (Yannis Varveris, Savoir Mourir)

Is there a more serious, more profound and more unsettling disruption of daily routine, of habitus, of temporality for a close-knit community than the death of a person? How does one deal with that disruption of temporality at the emotional, affective level? How does that rupture reorganise time, familial-social bonds and habitus? How does one deal with the embodiment of death, with its sensuous and sensory impact? Indeed, when is a person really dead, since the physical presence of that person, long after stopping breathing and talking, continues to act upon others, in a haptic, olfactory, multi-sensory and inevitably affective manner, its flesh transformed into something else?

For the people of the third and early second millennium BC Crete (roughly 3100–1700 BC, Early Minoan [EM] I–Middle Minoan [MM] II; see Table 18.1), these matters were of fundamental importance. Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to say that their communities were made and unmade in the arena of death. But we now know that these communities were regionally diverse, and their way of death and its aftermath were hardly singular and homogeneous (Legarra Herrero 2009). Take the people of the Mesara, for example, in the fertile, south-central part of the island, and the people living farther north, at Archanes, nearby Knossos (Figure 18.1). What did they do with their dead? It would be a misrepresentation to say that they buried them. That would imply distance, concealment and no directly embodied, visual, olfactory or tactile contact with the dead person. Instead, they built monumental, elaborate, stone and circular ‘houses for the dead’, arenas of communal gathering for dead and alive alike. They could have thrown the dead corpses into the sea, left them to be consumed by animals, abandoned them in remote places to vanish without a trace, as several societies do (Ucko 1969). But instead of dispersal, they chose accumulation and hoarding (Gamble 2004). Instead of solitary inhumations (as seen in other contemporary societies, for example in the Cycladic islands; Broodbank 2008: 59; Wilson 2008: 84–85), they chose public collective assembling, above ground. And they placed these monumental arenas at the centre of their social life, for several hundreds of years. These were places of return, of repetition, of citation, of recollection.

| Prepalatial | Early Minoan (EM) I | 3100–2700 |

| Early Minoan IIA | 2700–2400 | |

| Early Minoan IIB | 2400–2200 | |

| Early Minoan III | 2200–2000 | |

| Middle Minoan (MM) IA | 2000–1900 | |

| Protopalatial (‘Old Palace’ period) | Middle Minoan IB | 1900–1800 |

| Middle Minoan II | 1800–1700 | |

| Neopalatial (‘New Palace’ period) | Middle Minoan III | 1700–1600 |

| Late Minoan (LM) IA | 1600–1500 (in ‘high’, absolute chronology: 1700–1600) | |

| Late Minoan IB | 1500–1450 (1600–1500 in ‘high’ chronology) | |

| Late Minoan II–Late Minoan III | 1450–1100 (1500–1100 in ‘high’ chronology) |

Figure 18.1. Map of Crete with the sites mentioned in the text (adapted from Rehak and Younger 1998).

A dead person is carried to a tholos tomb from a nearby village, along with objects, some belonging to or perhaps relating to the dead (sealstones, figurines, stone vases), many, perhaps most, for the funerary ceremonies. As you enter the dark, humid spaces of the tomb through the only opening (its small and low entrance), in some cases having to crawl in and even pull the corpse from inside, you are in a different world. You are disoriented, but only temporarily. Darkness, lack of space for movement and, above all perhaps, the strong odour of decomposing flesh, amplified by the enclosed, hemispherical space, transports you to a realm both spatially and temporality distinct, and markedly different from that of the everyday. Yet you have been here before. The smell is familiar, and the flickering light of the lamp aids the recognition of the micro-regions of the tomb. In some cases, you can even recognise distinctive objects, peculiar stone and clay vessels, and the odd sealstone, metal dagger or figurine. You recall persons long dead, you start making associations, you connect bones, skulls and objects with times, places, living persons.

With the rest of the congregation, you deposit your dead at a corner, a micro-locale identified by yourself and by others as the one that belongs to your side of the clan, next to familial dead. You take up some clay or stone vessels you brought with you; in this dark space, it is your touch that can see. Your hands can tell which vessels contain what, not only because of their visually distinctive shape but also because some of them carry plastic or incised patterns and decoration, thus enabling haptic recognition. You apply some of the perfume and unguent onto the dead body, and perhaps some onto the participants as well. Odour envelops and incorporates. It invades human bodies at will, and it is difficult to control and contain. Through the strong sense of smell, dead and alive become one, they become a trans-corporeal landscape. You deposit some objects next to the dead, and then perform a series of ceremonies, some inside, perhaps mostly outside in the open spaces around the tomb, which in some cases, most likely in the later stages of the tomb’s use, were especially landscaped with walls and terraces to accommodate the increasingly large number of participants (the case of Agia Kyriaki, for example; Blackman and Branigan 1982; for other cases, see Branigan 1993). There is drinking, in some cases eating, dancing and possibly music. Psychoactive substances could also have been used, as indicated by the vessels imitating, in some cases very closely, the pod of the opium poppy (e.g. EM I Koumasa; Xanthoudides 1971 [1924], pl. I). Eating and drinking together, becoming intoxicated together, strengthen the bonds that connect you with everybody else around you, including the non-breathing but still active and participating corpses.

Eating and drinking is an act of in-corporation itself, but commensality in-corporates you further into the collective body of the community. Intoxication and consumption of psychoactive substances transports you to other places and other times. You become a participant in a performative event. In this highly emotive setting, the sensory impact of materiality is stunning: it is the sensuous impact of eating, of drinking, of intoxication; of witnessing the corpses, and experiencing the odour of decomposing flesh, mixed up with the odour of perfumes and, in some cases, of cooked meat; of seeing and handling unusual objects, made of rare and exotic raw materials, in strange shapes and colours: multicoloured stone vases and beads, metal daggers and long, shiny obsidian blades, figurines, exquisitely carved seals made of ivory and rare stone, animal-shaped containers, painted and incised pots. The aesthetic impact of these objects would have been much more pronounced upon bodies in altered states of consciousness. Some of these objects possess long histories, embodying remote times and faraway places, objects often linked sensorially with their odorous, powerful and intoxicating content. This immense and dazzling sensorial-aesthetic impact produces strong and persistent memories, a type of prospective remembering (Sutton 2001), remembering for the future.

In this structured, heterotopic locale (a place of a different order, divorced from the rhythms of daily life; Foucault 1986), the temporality of everyday has been suspended. You, however, participate in the production of a temporality of a different kind and scale; you feel part of a long, ancestral lineage and continuity. Among the sensorially stunning and dazzling materials around you, the ones that have come from faraway are either complete objects or recognisably imported raw materials (e.g. obsidian, marble and silver from the Cyclades; occasionally exotic stones from Egypt; Bevan 2007: 98). Others would have been made of more familiar, Cretan materials, but would have pretended to have come from exotic places, citing and imitating, for example, Egyptian or other motifs (Bevan 2007: 99). Others still would be in familiar forms and materials, but due to the wide circulation and use outside the funerary arena, they would have accumulated a long history and pedigree. Given the use of the tomb for hundreds – in some cases many hundreds – of years, some of these objects would appear to you as heirlooms, if not as ‘archaeological’ objects (Lillios 1999). All these objects and artefacts thus condense time and space, materialise multiple spaces and times simultaneously, and embody an ancestral geography. This is a geography that is perhaps mnemonically linked to places of mythical ancestral origin, loosely corresponding to the potentially multiple regions whence successive waves of immigrants came to Crete (during the Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age) (Betancourt 2008: 93–94), and/or the regions and places that were now linked to Crete though long-distance travel and exchange. I have called these mortuary contexts ‘chronotopes’, a term proposed by the theorist Mikhail Bahktin (Hamilakis n.d.), or rather ‘chronotopic maps’, contexts where ‘time as it were thickens, takes on flesh, becomes … visible…’ (Bakhtin 1981: 84).

You leave, knowing that you will return, time and again, to visit the recently dead, but also when another person from the villages dies. And when you come back, the memories of your previous visits will come flooding back, not in a tightly organised, linear and chronological manner, but chaotically, mixed up, commingled, much like the commingled corpses you will meet inside and around the tombs. After a certain time, the non-breathing body that you carefully placed, on its own, inside the tomb, the person that was still part of the social unit, and which was still active together with you, by being there seemingly bounded, distinct and visible, by being materially transformed, by emitting strong odours, ceases to be. Or rather, it ceases to be a continually active social person. Whatever is left of the corpse is pushed aside, piled up with other bones, flesh still attached to some of them. It is time for new space to be created, so that the more recently deceased can find their place. New space needs to be created in social memory (Hamilakis 1998). Time for forgetting, or rather time for the creation of new, positively valued, space for remembering (Battaglia 1990). Time for remembering anew, recalling new persons, social actors, events and situations. Hence, all the practices denoting forgetting: the piling of previously distinct and bounded bodies into anonymous heaps, their disarticulation, their covering with a layer of soil, their breaking, their pounding, even the burning of what is left of the corpses (more characteristically, in the recently discovered cemetery at Livari in East Crete, where a significant part of the human bones were found burnt; Triantafyllou 2009). It is not that these persons will be forgotten as such; it is that they will now be remembered not as social actors still partaking in the rituals of social life, but as ancestors, defined by a different temporality.

The interplay and the dialectic between remembering and forgetting, however, operated at different levels. Even after familial social persons had become ancestors, the need to maintain a link with them would have been present. Indeed, in many of the communal tholos tombs of the Mesara, we witness strategies that, within the shared and collective burial arena, attempt to compartmentalise and subdivide the burial space, to group, arrange and redeposit bones and skulls in discrete locales: internal, subdividing walls in Kaminospelio (Blackman and Branigan 1973), Merthies and Plakoura (Pendlebury 1935); a stone-built, niche-like compartment in Lebena-Yerokambos II (Alexiou and Warren 2004: 56) (Figure 18.2); a collection of skulls and bones and careful deposition outside the tomb at Archanes Tholos G (Papadatos 2005) and elsewhere; use of clay coffins (larnakes) as sub-compartments and subdivisions of the tomb, containing multiple bodies and body parts (examples from Archanes Tholos G and E, Vorou A, and several other sites; Branigan 1993) (Figure 18.3).

Figure 18.2. Plan of the Lebena Yerokampos II tomb, with the niche highlighted (modified from Alexiou and Warren 2004, fig. 12).

Figure 18.3. The interior of Tomb Gamma at Archanes (stratum II), from the west: larnakes after the removal of most of the bones (photo courtesy of Yiannis Papadatos).

Larnakes in particular are not only encountered towards the end of the Early Bronze Age, as conventionally thought. Rather, they are present from the start of the Early Bronze Age, as in the case of the Pyrgos cave, where 20 larnakes were found in an EM I–II context (Xanthoudides 1921). The use of larnakes has been linked (e.g. Branigan 1993: 66) to the emergence of the individual, but I have proposed instead (Hamilakis n.d.) that both the use of larnakes, and all the other compartmentalising material strategies outlined above, are not expressions of individualism but rather attempts to render discrete and thus recognisable and traceable the ancestral corpses. As such, they are materialisations of ancestral remembering, attempts to delay complete forgetting, to map, identify and materialise discrete ancestral links and associations.

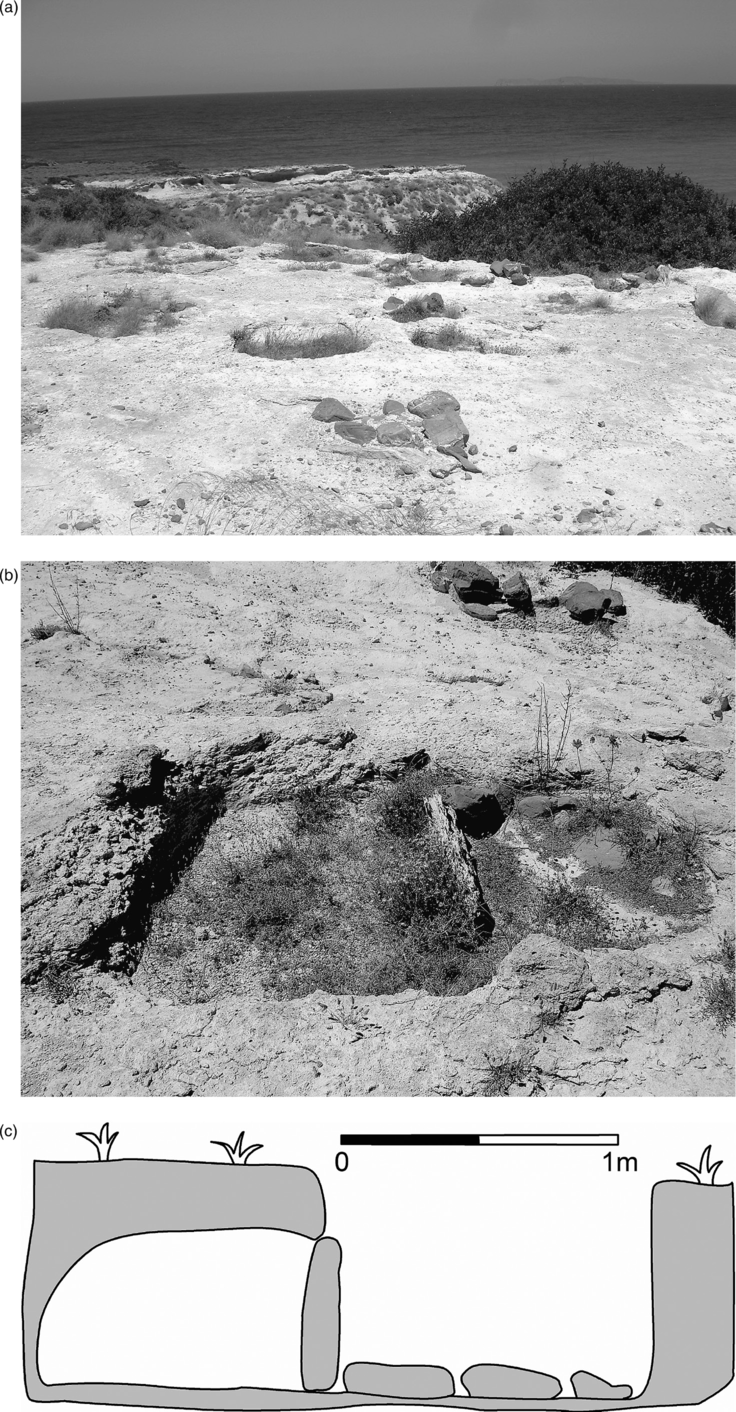

There was more than one sensory, experiential regime associated with the funerary arena in Early Bronze Age Crete. If you happened to live in the north or on the northeast coast of the island in EM I, and you were perhaps associated with communities that had distinct cultural identities, maybe emphasising an association with the Cycladic islands, then both as an alive and as a deceased person you would experience death differently from the rest of the island. Instead of the circular, built tholos tombs, you were likely to visit and eventually end up at a small, almost claustrophobic pit grave, shallow rock-cut tomb, or a slightly larger – but still tiny by the standards of the rest of the island – built tomb (e.g. Agia Photia cemetery in East Crete; Davaras and Betancourt 2004; Gournes cemetery in central Crete, near Irakleion; Galanaki 2006) (Figures 18.4a–c).

Figure 18.4. (a) The EM cemetery at Agia Photia (photo: the author, August 2011). (b) A tomb from the cemetery at Agia Photia (photo: the author, August 2011). (c) Section of tomb 218 at the Agia Photia cemetery (redrawn from Davaras and Betancourt 2004: fig. 493).

While at least on some occasions these tombs were used more than once, the regular pattern of visitation, of repetition, of continuous accumulation and hoarding of corpses and objects that we saw above were absent. After you placed the corpse inside these small spaces, along with clay pyxides (small pottery containers), some obsidian blades and perhaps a few other artefacts, you would drink, mostly from the communal drinking vessel of the time, the chalice (as you would have done in other burial contexts at the same time), passing it round among your fellow participants, although in some cases you would pour your drink from a jug into individual cups. You would not be able to experience the monumentality of the tomb, as you would have done in the Mesara for example, walking from the open air to the enclosed and dark space of the tholos tomb. You would not have been able to move insidethe tomb, often passing through various compartments, or touch and smell the hundreds of corpses, at various stages of decomposition, as you would have done in the tholoi. The funeral would have been probably attended only by a handful of people (judging by the quantity of pottery). When you left, you would have sealed the doorway of these small tombs with stones (Davaras and Betancourt 2004: 240–41), you would have left the dead behind, breaking your link with them. In these contexts, forgetting seems to have been more important, and long-term history and ancestral heritage does not seem to have been valorised. Here, your dead seem really to die, both as a physical and a social person, at the end of the funeral. You want to ‘kill’ the memory of that person, by rendering the objects associated with them redundant, devoid of their agency: by bending a dagger or by smashing the chalice that served the drink during their funeral (Davaras and Betancourt 2004: 240).

It would be a mistake to say that memory was not important for the communities that used these ‘Cycladic’ Cretan cemeteries. It was – otherwise they would not have gone to the trouble to construct these tombs, to perform these ceremonies and to deposit these objects along with the corpses. It was, however, a different perception and enactment of memory, one that places more emphasis on forgetting and on closure, one that does not require constant activation through repetition, citation and retracing of ancestral links and continuities, as happened with the tholos tombs. These two different perceptual modes of memory may correspond to the different histories of habitation and attachment to landscape, juxtaposing the relatively short-lived ‘Cycladic’ presence on the north coast with the long-lived engagement with place in the south-central part of the island.

Caves were used in some cases, continuing the Neolithic tradition (Zois 1973: 85), where practices similar to ones witnessed in other types of funerary contexts (especially in tholos tombs) were taking place: intense and repetitive ceremonies, eating and drinking, moving and mixing the skeletons, use of larnakes to subdivide the space (e.g. the most striking example of the EM I–II Pyrgos cave, mentioned above; Xanthoudides 1921). Phenomenologically, the funerary ceremonies inside a cave or rock shelter (unlike the small, cave-like rock-cut tombs) resemble very closely the experience of the built, circular tholos tomb. Indeed, Branigan (1993: 38–39) has suggested that the built tholos tomb imitates or replicates caves. Assuming that this observation is valid, two important points offer themselves: the first is that we witness here a mnemonic citation of a long ancestral tradition that goes back to the Neolithic; the second is that in building the tholos tomb, the replication of the sensory experience of the cave was more important than, say, functionality or hygiene (as we today perceive it); otherwise, why would you leave no openings? The dead, in a sense, were taken on a journey that led back to ancestral places – a journey, however, that both dead and living needed to make regularly, in order to retrace links and reactivate mnemonic connections.

From the EM II period onwards, rectangular, built tombs (sometimes called ‘house tombs’), with no apparent openings other than the entrance (sometime accessed through the roof), become prominent, especially in the north coast of eastern Crete (e.g. Mochlos, Gournia, Palaikastro, Petras, Sissi), but also elsewhere (e.g. Archanes, Koumasa in the Mesara; Soles 1992: 114–201). These too are regularly visited, communal mortuary spaces, often involving the post-funeral selection, grouping and rearrangement of bone and skulls. These combine, in a hybridised manner, elements found in other mortuary traditions of Crete and the southern Aegean at the time (rectangular shape, built form, as in the Cyclades, but also communal, largely above ground, and large enough to allow the movement of people through them, as in south-central Crete). In some cases, they have also been characterised as ‘organic’ (Soles 1992: 210–11), since they incorporate the natural bedrock into their architecture and they use local stone for the rest of the building, thus giving the visual and tactile impression of being part of the wider natural landscape, not a human-made addition to it. These features bring them closer, phenomenologically, to caves, citing thus again older ancestral traditions that originated in the Neolithic. At the very least, here too as in the Mesara tholoi, revisiting and enacting the past materially was the crucial feature, evident not only in the regular visits and rearrangement of the bones, but also in the hoarding and curation of heirlooms: in at least one case, at Gournia, EM II vessels were found placed in a pit, inside tomb I, thought to have been built in MM I (Soles 1992: 9). These EM II vessels are believed to originate from the EM II tomb III, which collapsed. People took care to redeposit these in the later tomb. Even if tomb I was built in EM II and continued to be used through to MM I, the existence side by side of material that would have been clearly identified as coming from another time would have materialised and embodied strong mnemonic connections.

In the routine sensorial habitus of the everyday, all these funerary locales provided an extremely intense aesthetic stimulation, a multi-sensory phantasmagoria. Every visit to such as heterotopic mortuary space was an event of special significance, a break from the temporality of daily life. The emotive and highly charged ceremonies around death provided opportunities for people and communities to come together, to engage in commensal practices involving food, drink and psychoactive substances, to witness rare and exotic artefacts and objects, but at the same time to move, collect, recollect and arrange skulls, bones and objects. They would have left with strong emotions, and even stronger memories, having traced and retraced geographical and chronological links, having mapped and remapped genealogical connections and associations. These were mnemo-scapes, places where people produced their own history and temporality, through strong sensory and sensuous experiences.

Through these contexts and events, time as memory – as ancestral links and associations, as mnemonic connections to places and past people, but also evocation, citation and recall of geographically remote places – became important political resources. Such resources were unequally distributed, as not all persons and clans, not all communities and regions, could have demonstrated the same richness and intensity in these mnemonic connections and links, the same time depth and longevity. Not everybody would have been able to amass the same material resources that could produce strong emotive and aesthetic-sensory impact upon the bodies of the participants. There are at times significant differences in the type and quantity of precious, exotic material found in different tombs, and the same asymmetry is witnessed in the time depth of use. The pattern is also regionally diverse, with the Mesara demonstrating a remarkable persistence and time depth in material practices and ceremonies, in comparison to, say, the northeastern part of the island.

Asymmetries bring tensions, especially at a time, such as the end of the Bronze Age, when some mortuary contexts become the gathering places of a larger congregation than before (Hamilakis 1998). The attempt to prolong ancestral remembering of specific people and groups within the communal space of the tombs through the various strategies of compartmentalisation and separation described above would have elicited opposition by others who would have insisted on the communal, shared ancestral memory. Finally, the nature of mnemonic recollection itself – its at times involuntary, spontaneous character, its ability and agency to spring up unexpectedly and disrupt the created mnemonic consensus – would have produced further tensions (Hamilakis 2010). The omens were not good.

‘Palaces’? A Mnemonic Approach to the Question of the ‘Emergence’

Conventional approaches to Bronze Age Crete have been fixated with the question of the so-called palaces. Why did they emerge? Who was involved? Who lived in them? What was their function? Why in Crete and not in other regions, e.g. in mainland Greece which has far greater agricultural potential? Why Crete and not other Mediterranean islands of comparable or greater size? Increasingly, it has been realised that while some of these questions are still valid, others have exhausted their interpretative potential. Any attempt at an explanation will have to start by defining what is to be explained in the first place. If change is what we are trying to understand, what exactly has changed and in what direction? In this case, it is rarely clear what the entity to be explained actually is: is it a series of monumental buildings located at certain sites? If so, which phase of that building and which architectural structure exactly, given the continuous destructions and rebuildings of monumental edifices on the very same spot? Is it a novel centralised institution that, supposedly, exercised political, economic-managerial/redistributive, and administrative (not to mention ideological) control over its region, if not over the island as a whole?

These two issues are often conflated, but it is the latter that many cultural-evolutionist discourses advocate, having imported wholesale ideas developed by Service (1962) and other authors, complete with a typology of social forms (tribe, chiefdom, state) and a checklist of attributes to go with each type (urbanism, administration, ranking, subsistence redistribution, craft specialisation, and so on). Only models such as Service’s on subsistence redistribution as a path to centralised authority have been discredited (e.g. Earle 1977; Pauketat 2007); as shown below, they also lack any firm empirical support on Bronze Age Crete. The often anachronistic use of Linear B data and the political organisation they imply (themselves a matter of considerable debate) to interpret the ‘palatial’ question many hundred years earlier is symptomatic of the confusion.

Other forms of homogenising and anachronistic thinking are evident in the discussion of the palatial phenomenon in the MM and Late Minoan (LM) I periods. Court-centred, monumental buildings are at the centre of attention, and the assumption is often made that the neopalatial ones are a further development of more or less the same form to be found in the protopalatial, court-centred buildings. But we now know that these complexes, despite certain similarities, are regionally diverse and did not develop at the same time everywhere, whilst the ones associated with the protopalatial period are very different from the neopalatial and much more archaeologically visible ones. The protopalatial complexes are smaller but more accessible than the neopalatial ones; they lack architectural features commonly associated with palaces, such as ashlar masonry, lustral basins and elaborate second floors, features that, interestingly, at sites such as Malia, are found in elite residencies in the town, not in the palace (Schoep 2004; 2006). In general, major innovations in architecture, administration and writing, pottery styles and long-distance movement of objects, often attributed to the agency of the palatial authorities in the protopalatial period, are now shown to be the outcome of diffuse social actors and groups, often residing outside palatial buildings (as in Malia), and being possibly in competition with palatial elites (Schoep 2006).

A striking feature of the neopalatial court-centred buildings is their proliferation, especially with the discoveries announced in recent years (see reports in Driessen et al. 2002), but also the replication of certain features commonly associated with palaces in elite monumental buildings, sometimes in very close proximity to the palace, making any discussion of settlement hierarchy, territorial control and allocation of roles problematic (Hamilakis 2002). Even the first appearance of central courts themselves has become a much more complicated matter, and it cannot be linked chronologically or functionally to the conventional understanding of the palatial phenomenon. These seem to appear much earlier than originally thought: at Knossos, reorganisation of space and terracing took place in EM IIA (Wilson 1994; 2008: 87), and a central court was possibly created in EM IIB (Manning 2008: 109), about 500 years before the early palaces proper (conventionally considered to be MM IB). At Phaistos, the area that would become the central court in the protopalatial period had been a major arena for ceremonies since the Neolithic (Todaro 2009: 142), and the building activity associated with the first palace did not signal a sharp change, save for the addition of a monumental façade (Todaro 2009). At Malia, a monumental building with a court was built in EM IIB and, interestingly, was intentionally incorporated in the later, EM III/MM IA monumental structure (Schoep 2004: 245).

As for other features commonly associated with the palatial phenomenon, recent discussions and revisions render them equally problematic. Knossos was comparatively very large already in EM II (a minimum of 5 ha at the time; Wilson 2008: 88), although it grew much larger in EM III–MM IA (Whitelaw 2004: 243). Phaistos also increased considerably in size during the protopalatial period (Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou 2004: 443). Asymmetrical access to resources, objects and materials was evident in the mortuary record from the beginning of the Bronze Age (Soles 1988). Co-ordinated building and terracing projects involving the mobilisation of a large number of people are also evident from the start of the Bronze Age in at least some of the very large tholos tombs, and in EM II monumental buildings and terrace walls at Knossos, Malia and elsewhere. Some sort of ‘administrative’ technologies and practices were present from at least EM II in the form of object sealings (Schoep and Knappett 2004: 26), and as for the earliest undeciphered forms of writing technologies (hieroglyphic, Linear A), these have shown no clear links with centralised authorities, given the date of their introduction, their diversity and their dispersal in many different contexts (Schoep 1999; Schoep and Knappett 2004).

Craft specialisation and extensive networks of exchange were also present even in the Neolithic (Tomkins 2004), let alone the Early Bronze Age (e.g. Day and Wilson 2002; Whitelaw et al. 1997). As Whitelaw (2004: 236) notes, however, ‘there is no evidence that either production or distribution was centrally organised, and there is no evidence for redistribution’ (see also Day et al. 2010). The absence of clear signs of a leader or head of a state is now widely recognised (e.g. Driessen 2002; Manning 2008: 199), and an increasing number of researchers accept the possibility of factional corporate groups, unified by shared ideological and cosmological beliefs, including perhaps shared notions of ancestral time and origin, but engaging in intense conspicuous consumption and material, competitive ‘wars’ (Hamilakis 2002; Schoep 2004; Manning 2008: 199), not only in the neopalatial period, for which this idea was originally proposed (Hamilakis 2002), but also for the protopalatial as well, as least in contexts such as Malia (Schoep 2002). Crop specialisation and subsistence redistribution lack any empirical support in Bronze Age Crete (Hamilakis 1995; 1996). As for centralised storage, and thus the ability of the assumed palatial authorities to act as redistributive agents, the data are rather dismissive: both the early palaces (of the protopalatial period) (Manning 2008: 118), and the later palaces (of the neopalatial era) (Christakis 2008: 120; 2011) had, comparatively speaking, rather limited storage capacity in staple agricultural products.

It is thus surprising that even scholars who acknowledge this lack of evidence are reluctant to let go of cultural evolutionist typologies, perhaps because the use of terms such as states provides the illusion of an explanation, or at least conjures up an image of a seemingly familiar entity. Research in the last 15 years or so, however, has shown that the court-centred buildings and their associated structures, rather than being centres of political authority, large-scale production of commodities, administration and subsistence redistribution, seem to be primarily centres of consumption, feasting and drinking, elaborate ceremony and performance (Day and Wilson 1998; Driessen 2002; Hamilakis 1995; 1996; 1999; 2002). Wine and olive oil, central to ideas of Mediterranean polyculture and subsistence redistribution, far from being staple subsistence commodities, were rather key substances linked to embodied ceremonies and sensuous interaction: wine due to its alcoholic properties, and olive oil as a base for perfumes and unguents (Hamilakis 1999).

Feasting and drinking ceremonies but also public consumption of material culture, especially that associated with the serving of food and drink, seem to become intense and conspicuous during the period we call protopalatial, compared to what was happening before (Hamilakis 1995; 1999). It is no accident that the pottery style most closely associated with the palatial phenomenon in the protopalatial period (although its introduction precedes the emergence of the palaces as conventionally understood; Momigliano 2007), the lavish, technically elaborate and aesthetically stunning Kamares ware, was produced mostly outside the palaces, and was linked to drinking ceremonies (Day and Wilson 1998). Equally, the introduction of the pottery wheel at the end of the Prepalatial period and the intensification in its use during the protopalatial period (Day and Wilson 1998: 352) to produce mostly drinking vessels (other shapes were wheel-thrown much later), often imitating metal forms (Knappett 1999; 2005: 156–62), coincides with intensified drinking ceremonies, possibly denoting a specific etiquette and aesthetic of drinking.

In other words, the prime concern of elites at the time was not a centralised administration and control of production, but a strong aesthetic and sensuous impact in ceremonial occasions. Power dynamics were played out in the arena of corporeal flows. While in the first century of the archaeology of Bronze Age Crete the question of the palaces was framed as a problem of hierarchy, leadership, territorial control, and accumulation and redistribution of material and symbolic resources, in this second century the question increasingly is being reframed in a rather more productive manner. Why the huge emphasis on and the intensification of ceremony, mass commensality, elaboration, conspicuous consumption and performance at certain moments? Why did certain places become the focal points for such elaborate, ceremonial activity, and not others? From where do these ceremonies and performances acquire their material resources and their potency, and what was their experiential import, their social consequences and effects?

It is my contention here that collective memory – produced, activated and reproduced through bodily, sensorial experience – may provide a more fruitful answer to these questions. We saw above how mnemonic, sensuous practices were performed in the mortuary arena. In discussing mortuary practices, I emphasised mostly the creation and reproduction of mnemonic links at the level of familial, generational and ancestral ties. I now wish to expand the argument further, and argue that sensuous practices can also contribute to the production, reproduction and commemoration of long-term mnemonic history. I would thus propose that what we see in the palatial phenomenon, in other words monumentalisation, intensification of ceremony, elaboration and conspicuous consumption, can be viewed more fruitfully as the materialisation, glorification and celebration of ancestral time, of long-term, mnemonic history. In explaining this argument further, there are three components I would emphasise.

(1) Sense of Place

Phenomenological philosophers, with Edward Casey (e.g. 1996) the most prominent, but also anthropologists (e.g. papers in Feld and Basso 1996), and some archaeologists have argued that a crucial property of remembering is its emplacement, its connection to specific locales that harbour remembering. Places and specific locales are constructed as special through bodily, collective experience. Places gather and hoard the memories from these experiences, memories that can be recollected and reactivated at a later time, during a return visit to the same place, or evoked elsewhere. Repetition and citation of collective embodied experiences in specific locales create a mnemonic weight that can be given duration and further agency through materiality.

The places we associate with the palatial phenomenon in Bronze Age Crete – Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and possibly Petras (to stay only in the protopalatial period) – were special locales long before the monumentalisation and conspicuous consumption we associate with the palaces. Knossos is, to date, the oldest settlement on the island, and although its size and status in the Neolithic may have been exaggerated (e.g. Tomkins 2008), it was the largest settlement already in the Early Bronze Age. It also has a long history of ceremonial activity centred around commensality that goes back to the Neolithic (Tomkins 2007), activity that became more prominent from EM I, as indicated by the hoarding of large quantities of communal drinking (chalices) and food-serving vessels in a deep well (Wilson 2008: 83), but also other feasting pottery from EM II.

Phaistos also has a long history of occupation going back to the Neolithic, and in the Final Neolithic the site stood out in the region, not only because of its long history but also because of its association with pottery linked to the serving of liquids and with other ceremonial activity (Relaki 2004: 177; Todaro and Di Tonto 2008). The most striking materialisation of mnemonic links at the site is the recent suggestion that the building activity considered to have initiated the ‘first palace’ at Phaistos (phase XI – MM II) involved not only the clearance of the previous buildings but also the reuse of old walls as foundations for new ones, the respect of location and the reuse of open communal areas established in EM II, and more importantly the ‘re-deposition of part of their floor assemblages in purposely made pits’ (Todaro 2009: 141).

Other sites in the region that would become prominent in the Palatial periods, such as Agia Triada, also offer plenty of evidence for ceremonial eating and drinking from the Early Bronze Age (Wilson 2008). Malia was occupied at least since the EM II, not to mention the tantalising hints for a much earlier, Neolithic occupation in the immediate vicinity (Tomkins 2008: 28–29). Petras was already an extensive settlement by EM IIB (Tsipopoulou 2002: 136), but the site seems to have drawn on a longer and deeper history. The protopalatial court-centred building at Petras is located on a hillside that faces, on the opposite hill to the east and only a few hundred metres from it, a Final Neolithic–EM I settlement (Papadatos 2008). Interestingly, it is on this same hill, and in the immediate vicinity of this Neolithic hilltop settlement, that the Prepalatial period people of Petras, who had since EM II established a settlement on the opposite hill, decided to ‘return’ their dead, a practice that included both house tombs and a rock shelter, and lasted right up to the foundation of the court-centred building in MM IIA. The burial rock shelter was not forgotten even in the neopalatial (LM IA) period, as finds of drinking vessels indicate (http://www.petras-excavations.gr).

All these places had become special through their long history of occupation and the repeated ceremonies of hospitality. In some instances, the successive occupation over many hundreds of years would have created an artificial mound (Knossos being the most prominent), a monumental, visible and tactile reminder of the long history of the site; in others, ruins of previous buildings would have served the same function. Moreover, we have become increasingly aware of deliberate attempts to create a mnemonic record of special events and ceremonies, by gathering, hoarding and thus preserving the material remnants, in pits, special deposits, wells and so on, a practice that aimed at materialising and making durable time and experience, thus creating material history (see Hamilakis [2008] for examples, and above, in relation to Phaistos).

(2) Sense of Embodied Commensality

It is no accident that the focal point of palatial buildings is the court, a place of gathering and ceremony, a place that acts as the arena for face-to-face, large-scale, embodied social interaction and public performance. At the same time, by being situated at the centre of the palatial structure, by being paved and adorned and so on, the space of the court itself commemorates the act of gathering and of communal interaction (Palyvou 2002; Vansteenhuyse 2002). Other courts and open spaces are also prominent. Paradoxically, it is the apparent emptiness of the court (especially the central court) that makes it easier for subsequent generations to incorporate it into their own architectural design. This emptiness, however, is more apparent that real, since the void of the central courts is replete with memories: memories of past events and ceremonies and of communal and performative interactions.

Central among the communal ceremonies and performances taking place in these courts were the rituals of eating and drinking, embodied events where taste and smell were of paramount importance. It was these in-corporating acts that brought all other sensorial experiences together. It was the mnemonic effects of eating and drinking that produced embodied remembering, linking people with each other and with the locales, spaces, objects and artefacts that partook of these ceremonies. The places that we call palatial have not only had a long history of habitation and use, but also a long history of communal eating and drinking, a long history of embodied commensality. Interestingly, from the EM II onwards, these commensal events, through the proliferation of jugs and other serving pots, and vessels such as ‘teapots’ with their elongated spouts, increasingly seem to emphasise the role of the host, and his/her ability to provide for the guests, rendering the act of drinking in particular more theatrical and performative (Catapoti 2005; Day and Wilson 2004).

(3) Sense of Ancestral Lineage and Continuity

In the first part of this chapter, it was shown how in the Early Bronze and first part of the Middle Bronze Ages sensuous and embodied memory in the mortuary arena was crucial in establishing familial links and ancestral connections. From the end of the Early Bronze Age onwards, I would argue, claims to ancestral lineages were performed much more intensely and competitively, both in the now transformed mortuary arena and in key settlement sites, which now acquire roles similar to the ones previously enacted by large communal tombs.

How is the mortuary arena now being transformed? We saw earlier that the communal tombs of the Prepalatial period enacted a dialectic between remembering and forgetting, between being able to trace lines of continuity with specific dead persons, and being able to relate to them only as the abstract collective of the ancestors. The arrangement of bones and skulls into piles, and the use of dividing walls, niches and larnakes to subdivide the communal space of the tomb, are indicative of this interplay. Towards the end of the Early Bronze and the beginning of the Middle Bronze Ages, however, such practices become more widespread and take more permanent and imposing material forms: larnakes are now used more often; small antechambers, creating many more compartments, are added to the tholos; and many late tombs are built with these antechambers as part of the original design (Branigan 1993). At the same time, some large tombs have paved areas and plazas added on to them, and judging by the ratio of cups to jugs where quantification is possible, more people participate in the drinking ceremonies (Branigan 1993: 27; Hamilakis 1998).

Some caves are used as ossuaries, and Agios Charalambos in the Lasithi mountains in east Crete is a characteristic and well-studied example. This important site seems to have received in MM IIB a deposition of a huge number of earlier skeletons and objects, spanning a long sequence going back to the Neolithic. These skeletons were sorted and carefully deposited, often arranged into separate groups within the cave, and were clearly at the centre of ceremonies involving eating, drinking and possibly music, as indicated by the presence of six sistra (a small percussion instrument) (Betancourt et al. 2008). If the tholos tombs of the Early Bronze Age can be seen as chrono-topic maps, as claimed above, this cave can be seen as a long-term mnemonic archive that hoards and celebrates (as it seems from the finds, literally) long-term history and ancestral memory. An effort to trace links to specific individuals would have been futile, but the attempt to sort bones and skulls, and subdivide the space by building walls inside the cave and using its natural niches and galleries, thus keeping some bones separate from others, speaks of a need to trace and maintain links not with specific persons but perhaps with clans, and specific places of origin.

What do all these changes indicate? That ancestral memory and long-term history become at this time more important resources in the arena of political economy and competitive power dynamics. The embodied and sensuous rituals of commemorating the dead, combined with the embodied rituals of eating and drinking in the mortuary arena, attracted more people than before, making the stakes higher and allowing for more intense competitive performances of ancestral authority and long-term history and continuity to be played out. In some cases, such as Malia, it was the mortuary arena, and more specifically the EM III/MM IA–MM II monumental enclosure of Chrysolakkos with its palatial features such as ashlar masonry (Schoep and Knappett 2004), built not far from the early court-centred building, that materialised in the most direct manner the sense of ancestral lineage and continuity, a sense indirectly commemorated in the court-centred building. In other cases, however, it was the non-mortuary, palatial site itself in general, and the monumental court-centred buildings in particular, that embodied that sense of ancestral power and long-term history. I argue that it is the eventual transformation of direct, embodied familial links (expressed in the identification, handling and manipulation of bones) into more abstract but still embodied ancestral-historical links with places of deep history that allowed specific sites such as Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and possibly Petras to act as monumental places, foci of elaborate ceremony, commensality and performance, and locales towards which many people gravitated.

Embodied, mnemonic weight and history and its political deployment would not have been enough. Other aspects of the phenomenon need to be taken into consideration. For example, palatial sites, especially during the protopalatial period, relied on an extensive hinterland of good quality agricultural land, whilst other sites, such as Mochlos, which in the Early Bronze Age had accumulated enormous material wealth through external contacts, lacked such hinterlands (Whitelaw 2004). Towards the end of the Prepalatial period, moreover, links with the eastern Mediterranean seem to become intensified, facilitated by improved navigational technology (Broodbank 2000; Manning 2008: 115). But these factors would not have been enough to explain the palatial phenomenon had it not been for the generation and deployment of long-term ancestral memory and history. Availability of agricultural resources or exotica on their own would have been inadequate without the symbolic resource of ancestral memory and history, and without the sensuous embodied collective rituals. Rituals of commensality and drinking events on a large scale were facilitated by access to prime agricultural resources; they produced new memories, but at the same time provided the performative, highly emotive environment for claims to power to be generated, epic journeys and ancestral feats to be narrated and orally transmitted, and exotic knowledge and objects to be exhibited, thus staging claims not only to remote times but also to remote places.

In a sense, however, the palatial phenomenon in Bronze Age Crete signified a victory of ‘indigenism’ and ancestral power over external contacts and externally generated senses of identity (see Robb [2001] for a similar argument regarding Maltese ‘temples’). While for much of the Early Bronze Age, Crete appeared to be extremely diverse in terms of material culture, hinting perhaps at diverse groups, or at least at diverse projections of identity, towards the end of the Prepalatial period, there is more homogeneity and an emphasis and celebration of the local past of the island, as opposed to its external contacts and links. Interestingly, while links with the east intensify at this time, the actual number of finished imported exotic objects is relatively small. With the exception of some raw materials, it is rather ideas and technologies that seem to have been imported (writing, faience, possibly the fast pottery wheel) rather than objects. Moreover, these ideas were adapted to suit the Cretan context and its history (Schoep 2006: 52–57). Exotica nevertheless would have been important as embodiments of geographical knowledge (Helms 1988), but given the highly competitiveclimate at the time, they were perhaps employed as part of competing discourses of power by groups that had access to long-distance travel, knowledge and acquisition. In fact, it may have been the intensification of external contacts, undoubtedly benefiting only certain groups, that would have led other groups and social agents to place more effort into the valorisation, celebration and monumentalisation of locality and its long-term history.

The palatial phenomenon therefore can be seen as the celebration, materialisation and monumentalisation of long-term, mnemonic ancestral history; this process, however, was highly contested. The phenomenon took its particular form through processes of competitive emulation (Hamilakis 2002; Schoep 2002; 2004) at a time when land (pack animals, carts) and sea (sailing) transport technologies facilitated further, intra-island communication.

Regimenting and Regulating Sensory Experience

The material effects of the ‘palatial’ phenomenon, the extreme elaboration and the conspicuous consumption and generosity, especially in the neopalatial period, more likely a by-product of intense competition among factions, created a material reality that transformed further the embodied and mnemonic experience of the people who participated in these intense ceremonial occasions. In the neopalatial period in particular (an extremely diverse material phenomenon), the sensory and sensuous experience of participating in ceremonies and gatherings in the palatial settings would have been dramatic due to the monumental scale of the buildings, the aesthetic impact of elaborate material culture, the multi-sensorial experiential import and effects of the ceremonies, and the number of people participating in the gatherings which, judging by the number of drinking vessels, and especially conical cups deposited (very often in a formalised manner), would have been very high. Feasting and drinking reach immense heights (Hamilakis 1999), and there is plentiful evidence for the consumption of psychoactive substances, such as the large numbers of so-called ‘incense burners’. Deliberate deposition and hoarding of material culture, very often involving paraphernalia of eating and drinking, now becomes a more widespread phenomenon than before, acquiring at the same time a more formalised and ritualised character (Hamilakis 2008; Hatzaki 2009; and for the deposition and hoarding of animal bones at Nopigeia-Drapanias, see Hamilakis and Harris 2011). The intensification of this phenomenon, which I have termed the production of a ‘mnemonic record’ on the ground (in addition to the bodily mnemonic record), speaks of an intensified effort to preserve the material remnants of collective ceremonial gatherings, to fix and objectify intense sensorial experiences.

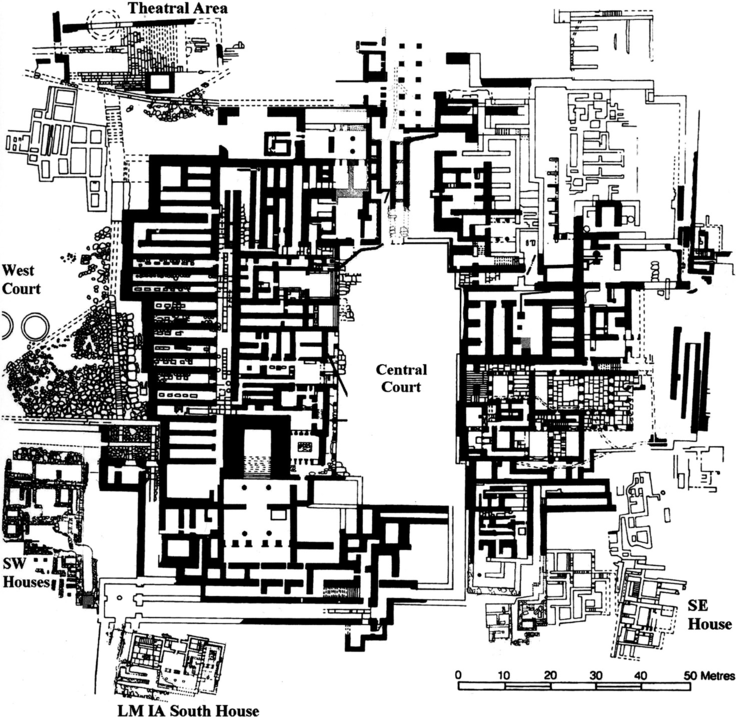

In the neopalatial period, therefore, ceremonial gatherings and events become much more ritualised, controlled and regulated, and human action and movement much more regimented, as a simple look at any architectural plan of a neopalatial, court-centred building with its labyrinthine human circulation patterns would reveal (Figure 18.5). As in previous examples and periods, however, there would have been a recurrent tension between the fluidity and ambiguity of sensory engagements and involuntary memory, on the one hand (how do you control smells? how do you tame memories?), and the attempt to regulate them and to fix meanings and bodily memories, on the other. The development of the palatial phenomenon signalled an intensification of this tension, one that reaches a new height during the neopalatial period. In that respect, the elaboration of architecture and its monumentality were not simply attempts to impress, to show off through conspicuous consumption. More importantly, they were attempts to regulate sensory modalities, to manage attention, through the regulated movement and conduct of the body, and the controlled sensory interactions that this entailed. As the stakes in the political arena increased, feasting intensified, with more people taking part in the embodied, fluid, sensory rituals of eating and drinking. At the same time, the need to regulate and fix meanings and memories became more important than before. Yet these sensory experiences would not necessarily have had the intended outcomes and effects, and their fluidity and unpredictability are perhaps hinted in the deliberate, successive and often selective destructions that we witness in Bronze Age Crete.

Figure 18.5. Plan of the Knossos ‘palace’ emphasising neopalatial (mostly MM IIIB) elements (modified from MacDonald 2002, pl. II).

Concluding Thoughts

Specialists on the Bronze Age of Crete often complain that in a number of key sites, successive rebuildings on the very same spot throughout the duration of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age obscure the archaeological visibility of earlier periods. They are, of course, right. But perhaps we should turn this phenomenon on its head and ask why there was this obsession with specific locales and why the same spaces, and in some cases, the same buildings and objects, were continuously reused.

I have attempted to evoke here the power of ancestral links and associations, and of long-term mnemonic history, as important features in the social life of Bronze Age Crete. These ancestral and historical links and associations were constructed through intense, sensory, bodily engagements, through sensuous bodily memory. And while one could say that individual or even collective, familial or generational memory, seen as an abstract, cognitive and mental process, may not extend back beyond a few generations, it is materiality itself that provides duration (Bergson 1991 [1908]), enacts time as co-existence and produces long-term mnemonic effects: places and landscapes that were visited and revisited, and where ceremonies were performed, leaving material traces; buildings, the remnants of which were visible and tactile for centuries; artefacts that were found when digging for the foundations of new buildings; objects that were circulating across inter-generational time, accumulating historical and mnemonic value on the way. This materiality, however, acquires its mnemonic and historical weight through intense sensuous and multi-sensory experiences, the handling and manipulation of bones, the taste and smells of food and drink in commensal events, the multi-sensory and kinaesthetic impact of moving through a ‘palatial’ building.

This is not an argument for an ancestor cult, nor for static attachment to locales and places, nor for essentialist, genetic links and continuities on behalf of Bronze Age Cretans. In effect, this chapter attempts to reinstate the people of Bronze Age Crete as fully embodied, corporeal, experiential beings, but also to grant them the right to produce their own mnemonic histories (or their own archaeologies?), based on existing or assumed and materially manufactured links, histories that were, of course, subject to various political deployments by diverse social actors.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the editors for the invitation to contribute to this volume and for their helpful comments, to Nicoletta Momigliano, to the participants of the 2011 Heidelberg ‘Minoan’ conference for feedback and reactions, and to C. for help in preparing the location map (and for everything else). All remaining errors are my own. Sections of this chapter, in a modified form, appear in Hamilakis (2013).