22 Stone Worlds: Technologies of Rock Carving and Place-Making in Anatolian Landscapes

Abstract

In this chapter, I explore practices of rock carving on the Anatolian peninsula from a diachronic perspective, with special emphasis on the Late Bronze Age and Early–Middle Iron Ages (ca. 1600–550 BC). Linking together the materiality of monuments, rock-carving technologies and issues of landscape imagination, I focus first on the commemorative rock reliefs across the Anatolian landscape, sponsored by the Hittite, Assyrian and Syro-Hittite states. Rock reliefs were carved at geologically prominent and culturally significant places such as springs, caves, sinkholes, rivers sources or along the river gorges. They constituted places for communicating with the underworld, the world of divinities and dead ancestors. I then venture into the Urartian and Paphlagonian rock-cut tomb-carving practices and Phrygian rock-cut sanctuaries of the Iron Age to argue for the broader dissemination of the idea of altering karstic landscapes for cultic and funerary purposes. I maintain that rock monuments can only be understood as always being part of a complex assemblage in the long-term history of places. Using a limited number of examples, this chapter contributes to studies of landscape and place in Mediterranean archaeology by promoting a shift of focus from macro-scale explanations of the environment to micro-scale engagement with located practices of place-making.

…the world into which we are thrown is always a built world … Building, which starts from the ground up, is where the fundamental ontology of our mundane lives both begins and ends … I intend the term ground both literally and nonliterally. Indeed it is because places come into being through acts of human grounding that the term possesses its literal and nonliteral senses. We know by now that the wherewithal of place does not preexist the act of building but it is created by humanity’s mark – its edified sign or signature – on the landscape.

Robert Pogue Harrison, The Dominion of the Dead (2003: 17–18)

As a child, whenever I was quizzed about my place of origin, I used to waver momentarily. This is because I have several that are mine. Ordinarily, I end up replying Ain-el-Qabou or, more accurately, in the local pronunciation, Ain-el-Abou, though the name doesn’t appear on any of my identity papers. Machrah is listed on these, a village very close to the first, but whose name is hardly ever used any more, possibly because the only road suitable for cars now turns away from Machrah and crosses the above-mentioned Ain-el-Qabou.

It is also true that this name has the advantage of corresponding to a concrete reality: ain is the Arabic word for ‘spring’, and qabou means ‘vaulted room’. When you visit the village, you see that there actually exists a gushing spring inside a man-made cavern of sorts with a vaulted roof. On the stone half-moon there is an ancient Greek inscription that was once deciphered by a Norwegian archaeologist: it is a biblical quote starting with ‘Flow, Jordan, flow on…’ The source of the Jordan River is about ten kilometers away, but in Byzantine times, these kinds of inscriptions were probably a traditional way of blessing the waters.

Amin Maalouf (Trans. Catherine Temerson), Origins: A Memoir (2008: 43–44)

Introduction: Springs, Rock Carving and İvriz as a Place of Deep History

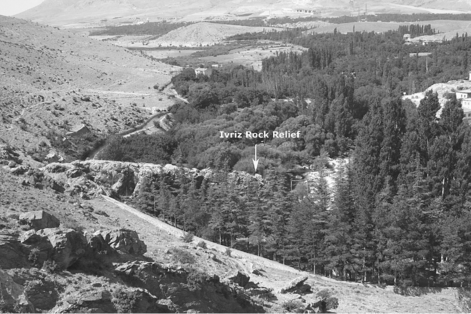

At a place called İvriz, in the northern foothills of the Taurus-Bolkar Dağ massif, near the modern town of Ereğli and close to the historical route that connects Cappadocia to the Adana Plain and the Mediterranean, there is a well-known spring. The seventeenth-century Turkish geographer and traveller Katip Çelebi, also known as Hajji Khalifah, gives a detailed description of the rock relief in his Cihannuma, where he identifies the place as Peygamber Pınarı (‘Spring of the Prophet’); he reports that its water and mud had healing qualities. Today, it is a pleasant and refreshing picnic spot visited by hundreds on any hot summer day. In addition to its gushing ice-cold water beneath tall walnut trees, İvriz is all the more powerful with its impressive vistas of the soaring limestone peaks and verdant valley of Ambarderesi, as well as its rock relief and ancient ruins. In antiquity, a series of rock reliefs and other monuments were carved into the living rock or raised in close proximity to each other, near the multiple mouths of the spring where fresh water pours from the rock. These monuments inscribed and re-inscribed this locality with multiple representations in text and image, grounding the place for cult activity and further animating an already eventful and geologically wondrous locale. The site is famous for its eighth-century BC rock relief depicting Warpalawa , ‘The King, the Hero, the Ruler’ of the regional kingdom of Tabal (Aro 1998; Hawkins 2000 [2]: 425–33) (Figures 22.1 and 22.2).

, ‘The King, the Hero, the Ruler’ of the regional kingdom of Tabal (Aro 1998; Hawkins 2000 [2]: 425–33) (Figures 22.1 and 22.2).

Figure 22.1. Rock relief of Warpalawaš, king of Tabal at İvriz, south-central Turkey (ca. eighth century BC). Photograph by Ömür Harmanşah.

Figure 22.2. Landscape at İvriz, south-central Turkey, with the view of Kocaburun Kayası, the site of the rock relief in the middle. Photograph by Ömür Harmanşah.

Facing south, the relief is carved on Kocaburun Kayası, an impressively prominent rock outcrop that extends into the space of the valley perpendicularly, long and thin. The ruler is depicted in veneration of ‘his’ Storm God Tarhunzas, and voiced in his monumental Luwian hieroglyphic inscription (Hawkins 2000 [1.2]: 516–18):

This (is) the great Tarhunzas of WarpalawaFor him let him/them put long(?) SAHANA(?)This (is) the image of Warpalawathe Hero…

Tiyamartus Warpalawa’s belo[ved?…] carved it…

In this chapter, I explore various practices of rock carving and the associated cultural practices on the Anatolian peninsula from a diachronic perspective, with special emphasis on the Late Bronze, Early and Middle Iron Ages (ca. 1600–550 BC). Looking across a variety of regional rock-carving practices in Anatolia, I aim to link together the material corpus of rock-cut monuments – such as the commemorative one of Warpalawa at İvriz – with broader practices of place-making and ontologies of place. While these monuments are either ritual, funerary or commemorative in nature (or serving more than one function at a time, which is arguably the case for most of them), it is argued that rock carving should first be understood as a technology of altering ‘natural’ places and has a lot to do with issues of the construction and inscription of places as culturally meaningful, politically contested locales. Bradley (2000: 33) refers to ‘votive deposits, rock art, production sites and the relationship between the monuments and the features of the natural terrain’, and states that they should be explored more carefully by archaeologists as a new form of landscape archaeology (see also Bradley 1993; 1998). Furthermore, the act of carving into the living rock is characterised as a direct encounter between cultural practices and the geomorphology of the terrain, which always provokes human imagination and storytelling in the most unexpected ways (for related ethnographic work, see, e.g., Sikkinka and Choque 1999; Cruikshank 2005). Rock carving, therefore, goes contrary to the compartmentalisation of landscapes into ‘natural’, ‘man-made’ and imagined components – it is all about the hybridisation of the three.

at İvriz – with broader practices of place-making and ontologies of place. While these monuments are either ritual, funerary or commemorative in nature (or serving more than one function at a time, which is arguably the case for most of them), it is argued that rock carving should first be understood as a technology of altering ‘natural’ places and has a lot to do with issues of the construction and inscription of places as culturally meaningful, politically contested locales. Bradley (2000: 33) refers to ‘votive deposits, rock art, production sites and the relationship between the monuments and the features of the natural terrain’, and states that they should be explored more carefully by archaeologists as a new form of landscape archaeology (see also Bradley 1993; 1998). Furthermore, the act of carving into the living rock is characterised as a direct encounter between cultural practices and the geomorphology of the terrain, which always provokes human imagination and storytelling in the most unexpected ways (for related ethnographic work, see, e.g., Sikkinka and Choque 1999; Cruikshank 2005). Rock carving, therefore, goes contrary to the compartmentalisation of landscapes into ‘natural’, ‘man-made’ and imagined components – it is all about the hybridisation of the three.

The monuments of concern here range from Hittite and post-Hittite (especially Syro-Hittite/Luwian and Assyrian) commemorative rock reliefs to Urartian, Phrygian and Paphlagonian practices of carving the living rock for cultic, commemorative and funerary purposes. Within the limits of this study, my intention is not to present a comprehensive survey or classification of such monuments. Instead, I emphasise the diachronic continuities (and discontinuities) in rock-cutting practices, assuming we can understand rock cutting as a cross-cultural technology of place-making in Anatolian landscapes. Especially within the karstic limestone geologies of the peninsula, I suggest that the heterogeneous practices of carving and inhabiting the rock are closely associated local, place-specific practices in long-term history. The making of such landscapes across the Anatolian peninsula can only be understood by drawing links between societies of different ethno-linguistic affiliations and emergent cultural identities.

The chapter also critiques the specialised art historical and epigraphic approaches to rock reliefs and rock-cut structures, which portray them as stand-alone monuments and show a certain disregard for their micro-geographical context. I argue that rock monuments can only be understood, always, as part of a complex assemblage in the long-term history of places. Within the last century, the archaeological richness and complexity of İvriz was slowly revealed through the discovery of new reliefs and rock features, documentation of an associated fortress and monumental buildings, and the excavation of a stele (Messerschmidt 1900–1906: 142–43, 320–23, table 34; Gelb 1939: 31 and pl. 46; Bier 1976; Rossner 1988: 103–15; Şahin 1999; on the bilingual Iron Age stele, Dinçol 1994; for a recent archaeological assessment of the area, Karauğuz and Kunt 2006). Immediately to the south of the main rock relief, archaeologists excavated a massive statue head and a fragmentary stele of the weather god with a bilingual Phoenician and Luwian inscription (Dinçol 1994). Slightly farther south, about 110 m from the major rock relief and on the very top of a rocky spur, is a small relief of a supplicant bringing a sacrificial animal, along with a series of stepped rock cuttings, and an offering platform (Bier 1976). Even in the absence of systematic archaeological work at İvriz, these finds alone suggest that in the 400–500 years following the fall of the Hittite Empire, the site continued to be an intensively used spring sanctuary.

From Site to Complex Landscape

Early in the twentieth century, along the now-dry river bed of Ambarderesi or Karanlıkdere, about one km from the well-known relief of Warpalawa , an almost identical rock relief was located. In order to get to this relief, one has to climb the steep saddle south of Warpalawa

, an almost identical rock relief was located. In order to get to this relief, one has to climb the steep saddle south of Warpalawa ’s relief in the slopes of the impressive Mt. Aydos. Climbing in the river bed of Ambarderesi, one enters a very narrow canyon, which used to be the other branch of the İvriz spring before its waters were diverted for a recent dam project. Halfway into this very steep and narrow gorge, one arrives at an area punctuated by a series of large caves. Two Late Antique/Byzantine monasteries (locally known as Oğlanlar Sarayı and Kızlar Sarayı) are constructed with mortared rubble masonry, right at the point where the canyon makes a sharp dog-leg turn. Facing northeast, one finds the second Warpalawa

’s relief in the slopes of the impressive Mt. Aydos. Climbing in the river bed of Ambarderesi, one enters a very narrow canyon, which used to be the other branch of the İvriz spring before its waters were diverted for a recent dam project. Halfway into this very steep and narrow gorge, one arrives at an area punctuated by a series of large caves. Two Late Antique/Byzantine monasteries (locally known as Oğlanlar Sarayı and Kızlar Sarayı) are constructed with mortared rubble masonry, right at the point where the canyon makes a sharp dog-leg turn. Facing northeast, one finds the second Warpalawa relief, an approximate but unfortunately badly weathered copy of the original presenting the same composition, only without the inscription and with certain minor differences in detail (Figure 22.3). This relief was noticed by E. Herzfeld in 1905 (Messerschmidt 1900–1906: 335–36) and visited by Gertrude Bell in 1907 (Barnett 1983: 73; Karauğuz and Kunt 2006: 29–30, nn. 23–27).

relief, an approximate but unfortunately badly weathered copy of the original presenting the same composition, only without the inscription and with certain minor differences in detail (Figure 22.3). This relief was noticed by E. Herzfeld in 1905 (Messerschmidt 1900–1906: 335–36) and visited by Gertrude Bell in 1907 (Barnett 1983: 73; Karauğuz and Kunt 2006: 29–30, nn. 23–27).

Figure 22.3. Second rock relief of Warpalawaš, king of Tabal at İvriz, Turkey, Ambarderesi valley. Photograph by Ömür Harmanşah.

This rare practice of carving the same composition at another important locale deserves close scrutiny through new fieldwork in order to address issues of re-inscription and associated site-specific practices. Finally, and most recently, on the high saddle that separates the two valleys, İvriz and Ambarderesi, archaeologists Karauğuz and Kunt (2006) surveyed the remains of a sizeable ancient fortress, for which they provided a possible, Late Iron Age date of 750–300 BC. The fortress seems to have seen continued use in the late antique and Seljuk periods.

Although often construed as a single rock relief in traditional art historical and philological scholarship, the site of İvriz embeds a complex landscape, a locale of deep history, a place of memory and imagination similar to Maalouf’s Ain-el-Qabou. It is not a unique example: every single one of the Late Bronze and early Iron Age rock monuments I have visited or studied appears to have existed within an intricate web of geological and archaeological features that unquestionably testify to long-term engagements of heterogeneous nature with places.

Perhaps two of the most fascinating examples of multiple inscriptions of place in the form of rock-cut images and monumental inscriptions over a long period of time in the Near East are the sites of Nahr al-Kalb in Lebanon and Bīsōtūn in Iran. At Nahr al-Kalb, 22 recorded inscriptions and reliefs were carved at the site, starting with one commemorating the Egyptian Pharoah Ramesses II (ca. 1270 BC), right next to numerous monuments of the Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian rulers (Volk 2008). The practice of carving reliefs and inscriptions was continued by the Mamluk Sultan Barquq in the fourteenth century AD, by Napoleon Bonaparte III in 1860–61 and by Lebanese president Alfred Naqqash in 1942. At Bīsōtūn, the famous Achaemenid-Persian relief of Darius I was later accompanied by Seleukid Herakles and Arsacid reliefs of military victory (Canepa 2010).

Rock carvings and their monumental inscriptions form only one component of a constellation of material features and residues that make up the places of long-term cultural practice in which they exist. This study approaches sites of this nature, where place-making practices by a variety of cultural groups in ancient Anatolia intimately engaged with the bedrock of places and left durable marks or shaped them within the social contexts of ritual, funerary and commemorative events and practices.

Karst Landscapes, Rock Carving and the Long Term

The middle and western Taurus Mountains, the southern parts of central Anatolia and some in the southeast feature karstic landscapes composed of Mesozoic and Tertiary limestones (Atalay 1998). These landscapes carry a wealth of ‘…karstic features such as karrens, dissolution dolines, collapse dolines, blind valleys, karstic springs, swallow holes, caves, unroofed caves, natural bridges, gorges and poljes’ (Doğan and Özel 2005). Karstic aquifers and other features that involve moving water, gushing springs and disappearing streams always provoked the imagination of local communities in antiquity; they were believed to connect the everyday world physically to the underground world (of the dead, the ancestors), thereby inviting and stimulating the inscription of such sites (Gordon 1967). Such meaningful interaction with the mineral world transforms eventful places into dynamic sites where geological and cultural processes are entangled in the long term.

The assumption here is that a spring is already an eventful place by virtue not only of the geological spectacle of water pouring out of the bedrock but also of the very basic human engagement in securing drinking water; this water is often regarded as sacred and healing, as it was at İvriz (Håland 2009). The frequently visited sacred places at springs, caves and sinkholes take on distinct social associations and highly specific cultural significance through sustained practices in the landscape, thus becoming sites of concentrated local knowledge and social memory (Boivin and Owoc 2004). When local bodies of knowledge are involved in exploring the stratified history and the significance of places, it is intriguing that geological formations themselves appear as actors (Cruikshank 2005: 1), or as animate beings – e.g. the mountains, rivers, springs, rock outcrops and ‘eternal peaks’ in Hittite Anatolia (Bryce 2002: 135).

From a long-term regional perspective, practices of rock carving offer substantial evidence for continuity across the Anatolian peninsula during the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. As argued in detail below, rock reliefs, inscriptions and other kinds of rock-cut monuments were always built at various geologically distinct locales: springs, caves, steep river gorges, sinkholes and rocky mountain peaks and passes – which by definition are places of sustained social practices. With respect to the early Iron Age, Syro-Hittite and Assyrian rock reliefs and inscriptions, as well as Phrygian rock-cut sanctuaries, we are on safe ground to suggest an Iron Age inheritance of Late Bronze Age technologies of inscribing rocky places with commemorative monuments.

Urartian, Paphlagonian and southern Anatolian rock-cut tomb carving provides another distinct yet related practice and relates to the broader dissemination of the idea of altering karstic landscapes for cultic and funerary purposes. The practice of embedding these rock locations with rupestral monuments to dead ancestors and local divinities is maintained right through the Hellenistic and Roman periods, even into late antiquity. The next section offers some critical insight into the particularities of such practices in their regional context and seeks to link them to the longer-term landscape imagination in ancient Anatolia. The discussion is intended to contribute to studies of landscape and place in Mediterranean archaeology by promoting a shift of focus from macro-scale explanations of the environment to micro-scale engagement with located practices of place-making. At the same time, it advocates further empirical research on places, to address the ontological nature of places rather than limiting ourselves to issues of representation and symbolism (Merrifield 1993).

Inscribed Landscapes

Hittite and early Iron Age rock reliefs in Anatolia are often seen to be politically motivated monuments that deliberately marked or guarded the territorial borders or important highways of antiquity (mountain passes, river valleys, etc.; see, e.g., Bonatz 2007; Seeher 2009; Glatz 2009 for important recent contributions). This standard commemorative reading of the monuments as imperial interventions to landscape derives from the long tradition of locating, ‘discovering’ and ‘deciphering’ these monuments – especially from the nineteenth century onwards – by renown travellers, antiquarians and Classical epigraphers of the last two centuries (most prominently in the late nineteenth century; Hirschfeld 1887). Such epigraphic and art historical studies of rock reliefs and extra-urban monuments have been instrumental for imagining ancient landscapes.

Reconstructing the historical geography of the Hittite Empire and the Iron Age polities of the Anatolian peninsula benefitted tremendously from ‘reading’ these firmly located monuments with inscriptions and images. Consider, for instance, the recent debate over the geographical definition of Tarhuntašša and the Hulaya River Land provoked by the discovery and publication of the rock relief at Hatip at an abundant spring near modern Konya (Bahar 1998; 2005; Dinçol 1998a; 1998b; for speculations on the geography of Tahuntašša in the light of landscape monuments, see Dinçol et al. 2000; Karauğuz 2005; Melchert 2007). In these debates, this commemorative monument of Kurunta, king of Tarhuntašša, became a boundary marker of sorts between that Mediterranean kingdom and the Hittite ‘Lower Land’. By virtue of their subject matter and the inscriptions permanently carved onto the living rock, such reliefs are seen as authentic sites to which ancient political geographies can be anchored.

The relationship of Hittite monuments and geography – especially in south-central Turkey – has thus been a major scholarly concern (Hawkins 1995: 49–65; see also Gordon 1967). In the case of lengthy royal inscriptions such as those in Hieroglyphic Luwian at the Yalburt Sacred Pool complex or in Hattuša’s Südburg, where many place names are recorded, the debate over the political geography is even more complex and heated. Shafer (1998) similarly explores Neo-Assyrian ‘border’ steles and rock reliefs as monuments that defined the periphery of the empire.

This methodology and the historical conceptualisation of rock reliefs and other extra-urban monuments have a number of limitations. First and foremost, the specific scholarly obsession with the internal elements of the monuments – e.g. dating, composition, iconography and philological content – led to the relative neglect of the specific locales, the micro-landscapes, the places in which such monuments serving collective memory are carved or set up. Notable exceptions to this trend are Ehringhaus’s (2005) volume on Hittite rock reliefs (with excellent photographs of the landscape) and Schachner’s recent survey of Source of the Tigris (Birklinçay) monuments in their geoarchaeological context (Schachner et al. 2009). By advocating an archaeology of place and place-making, I propose that it would be possible to get a contextualised and balanced understanding of these monuments as places where specific practices are exercised and as places with active roles in the everyday life of the local communities.

Second, a sharp contrast is usually assumed between these explicitly political commemorative monuments of the Late Bronze and early Iron Ages vis-à-vis the more funerary nature of Urartian, Paphlagonian and south Anatolian rock-cut architecture of later periods (Middle Iron Age to Late Roman); in turn, Phrygian rock-cut architecture is heavily associated with cult rituals. This implies a discontinuity in the nature of human engagements with the living rock. My intention here is to show that the evidence is far more complex. On the one hand, we see continuity in the commemorative and broadly politicised nature of rock carving in Anatolia; on the other hand, Hittitologists are increasingly convinced of the possible funerary functions of Hittite rock reliefs. I attempt to unpack these two issues below.

During the Late Bronze and early Iron Ages, ‘landscape monuments’ of the Anatolian peninsula often feature monumental inscriptions sponsored by a variety of regional powers, including the Hittite state and various Anatolian vassal states of the Late Bronze Age, and the Assyrian empire and the Syro-Hittite regional states in the Iron Age. I borrow the term ‘landscape monuments’ from Glatz (2009), with reference to Hittite rock reliefs, spring monuments, dams and quarries (see also Kohlmeyer 1983; Ehringhaus 2005; Bonatz 2007; Seeher 2009). In Anatolian and Near Eastern archaeology, Hittite rock reliefs are almost never discussed in relation to similar monuments dated to the Iron Age, even though there are strong indications for the uninterrupted continuity of the practice from the Late Bronze into the early Iron Age.

Many of the well-known rock reliefs were carved at liminal mountainous locations, overwhelmingly at geologically prominent and culturally significant places outside the cities – e.g. at springs and river sources, along the river gorges or on prominent rock outcrops. There are many instances where rock monuments also appear in urban contexts – e.g. at Boğazköy/Hattuša, Gavurkalesi and Kızıldağ. These reliefs and monuments created places of unusual human interaction, particularly places for communicating with the underworld, the ‘other worlds’ of divinities and dead ancestors. Hittitologists have recently pointed out a possible association of such monuments with a number of expressions in Hittite texts, especially in Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions, as well as in treaties and ritual texts. ‘Eternal Peak’ (NA4.HEKUR.SAG.UŠ) in the Hittite texts, for instance, is understood as a commemorative rock-cut monument (such as Nişantaş at Boğazköy), a memorial posthumously dedicated to a royal ancestor but not necessarily comprising a burial (Taracha 2009: 134; see also Van den Hout 2002: 74–75; on the etymology of hekur, see Puhvel 1991: 287–89). Rock-hekur has also been translated as ‘rock sanctuary’ and associated with sites such as Yazılıkaya (Puhvel 1991: 287; it is often compared to ‘Divine Stone House’ [É.NA4 DINGIR.LIM] or the hesti-house, both clearly associated with funerary installations; Hawkins 1998: 71).

There are a series of Imperial Hittite rock reliefs found along the Zamantı Su valley in the province of Kayseri in southeast-central Anatolia. Among these, the well-known rock relief at Fıraktın is carved on a volcanic bedrock façade, immediately above one of the tributaries of Zamantı Su; it overlooks a very green plain, has a spectacular view of the Erciyes Mountain and is immediately below an ignimbrite pumice-flow platform (Figure 22.4). Walking on the bedrock plateau immediately above the relief, one comes across several cup marks and circular basins, related to extensive quarrying activity. Only a few hundred metres northeast of the relief, there is a prominent rock promontory where one sees a dense artefact cluster and surface remains of a monumental building, at least 30×28 m in size. Cup marks and circular basins also cluster near this building. The thirteenth-century BC Hittite relief itself depicts the Hittite king Hattušili III and Puduhepa pouring libations in front of the Storm God Tarhunzas and the seated Hepat respectively. The hieroglyphic inscription identifies all of them by name, and Puduhepa is singled out as the ‘great queen, daughter of Kizzuwatna, having become god’, a well-known Hittite euphemism for being deceased. Similar associations of various rock-relief monuments of the Hittites may suggest that at least some of them could be associated with the ‘Eternal Peak’ (NA4.HEKUR.SAG.UŠ) or the ‘Divine Stone House’ (É.NA4 DINGIR.LIM), monuments to dead royal ancestors. These were not simply tombs or commemorative monuments but ‘large self-supporting institutions employing cultic, administrative and other personnel, and mostly enjoying some kind of tax exemption’ (Van den Hout 2002: 91).

Figure 22.4. Hittite rock relief at Fıraktın on the Zamantı Su river basin near Develi (Kayseri Province). Photograph by Ömür Harmanşah.

Rock reliefs and rock-cut monuments are commemorative in their often overtly political disposition: embedded in the geological temporality of the living rock, they act as a means of naturalising state power. While they attempt to construct territories of power, they connect political spectacles with the supernatural world of ancestors and cultivate grounds for everyday ritual practice, funerary or otherwise. While they appropriate existing local and located practices, geological wonders and symbolically charged landscapes into state discourse, they intervene in everyday practices that constitute the ontologies of place and processes of place-making. Those place ontologies and processes both involve discursive, programmatic interventions, directed inscriptions of place as well as residual assemblages and archaeological depositions that constitute localities of human practice and dwelling.

If rock reliefs can be considered as temporally specific and spatially situated inscriptions of place, they are thus constituted by hybrid temporalities: durable and long-term by virtue of their incorporation into geological processes, and spectacular and animating for the long-term maintenance of site-specific practices. The inscriptional practices involve the embedding of state narratives in the form of formulaic, discursive and annalistic texts as well as pictorial statements. Once they become entrenched in the bedrock of place, the materiality of the rock reliefs, their political and cultural significance, and their agency over the culture of place do not remain inert but evolve with the landscape in which they exist. Today, as modified geologies and cultural landscapes of antiquity, they link contemporary communities with the past through their poetic and mysterious aura as ruins, and the spectacle of their antiquity. Because they speak so concretely to the geneaologies of locales, whichever way they are understood and interpreted, they evoke and provoke cultural imagination and take part in the collective memory and shared senses of belonging to a place.

The rock reliefs set up in the frontiers of the Assyrian empire during the Iron Age are excellent examples of such blending of political ideologies, local cult practices and the colonial appropriation of culturally meaningful places. During their military campaigns, a series of Assyrian rulers carved their images and inscriptions on the walls of two caves at the source of Birkleyn Çay in the Korha Mountain, near the modern town of Lice in southeastern Turkey (Harmanşah 2007; see also Schachner et al. 2009; Shafer 1998: 182–88). The site and the monuments, known in Assyriological circles as the ‘Source of the Tigris’ or the ‘Tigris Tunnel’, were visited repeatedly by the Assyrian kings and their army (Figures 22.5–22.7). Based on Assyrian annalistic texts and pictorial representations of the event such as those on the Balawat Gate bronze bands, the carving of the images into the living rock seems to have been part of a series of commemorative and ritual activities at this sacred spot, including animal sacrifices, celebration banquets, the washing and raising of Aššur’s weapons, and the Assyrian king’s reception of tributes and offerings.1 Judging from the textual, pictorial and archaeological evidence, it is possible to argue that the Birkleyn caves were already a place of cultic significance and political contestation as a symbolic landscape even prior to the carving of the rock reliefs. Elsewhere I have argued that Assyrians were appropriating a local Hurrian/Anatolian practice of venerating DINGIR.KAŠKAL.KUR, ‘The Divine Road of the Earth’, associated with entrances to the underworld (Harmanşah 2007; on the ritual significance of Assyrian rock reliefs in general, see Shafer 2007).

Figure 22.5. ‘Source of the Tigris’ or ‘Tigris Tunnel’ site, Cave I entrance. Photograph by Ömür Harmanşah.

Figure 22.6. ‘Source of the Tigris’ or ‘Tigris Tunnel’ site, Birkleyn Çay gorge. Photograph by Ömür Harmanşah.

Figure 22.7. Relief image of Tiglath-pileser I on the Tigris Tunnel (Cave I) walls, with Tigris 1 cuneiform inscription to his left. Photograph by Ömür Harmanşah.

Assyrian rock reliefs in other frontier landscapes similarly adopt novel geological and locally sacred spots. Another excellent example is the site of Karabur where Taşyürek (1975) located four Neo-Assyrian reliefs (Figures 22.8 and 22.9). Karabur is a granite outcropping with conical bodies of bedrock about 25 km southeast of Antakya near the village of Çatbaşı (Karsabul). On the granite bedrock, Taşyürek (1979: 47) identified four distinct reliefs of divine and royal beings with no apparent coherent order in relation to each other, although he suggested the possibility of understanding the site as ‘an open air sanctuary’. What is fascinating here is the gathering of other archaeological features and the contemporary significance of the place, beautifully described by Taşyürek (1975: 174):

The importance of this monument lies not only with the Assyrian reliefs but also in a tradition of sanctity which even today attaches to the spot. As at Ferhatlı, the outer parts of the locality were used as a necropolis in Roman times. A rock-cut burial chamber of a characteristic Cilician type on the southern edge of the area suggested the possibility of the presence of further tombs, and in fact some questioning soon served to locate many other Roman graves. Another point of interest is a wall, probably Roman, found c. 100 m. north of the area of the reliefs at a spot surrounded by fir trees. The villagers of Çatbaşı, who speak Arabic as their mother-tongue and belong to the Alawite sect, regard this as a place of pilgrimage and name it Seyh ul Kal’a (‘Sheikh of the Fortress’). Around the Roman wall, which they regard as a tomb, and where on certain religious days they burn various kinds of incense, there are stones in the shape of orthostats, and about 7 m. to the north, there is an undamaged marble pool, probably also of the Roman period.

This rich multi-temporal engagement with rock-relief sites during the subsequent periods of antiquity is evident in the very material corpus of the place. The new meanings and associations linked to the rock monuments among the ancient medieval and contemporary inhabitants of the locales is a fairly common aspect of rock reliefs usually ignored in contemporary scholarship. The Late Bronze and Iron Age rock-cut monuments often drew Hellenistic graffiti, Roman quarries and rock-cut cemeteries, as well as Byzantine monastic establishments to the place; these associations are significant in arguing for the continuity of rock-carving practices on the Anatolian peninsula and for the cultural biography of places.

Figure 22.8. The site of Karabur with Neo-Assyrian rock reliefs near Antakya. Photograph courtesy of Elif Denel.

Figure 22.9. Karabur Neo-Assyrian rock relief near Antakya. Photograph courtesy of Elif Denel.

The Rocks of Phrygian Matar

Cult places associated with Phrygian deities, specifically the rock-cut monuments linked with the cult of Matar, have recently been subject to much archaeological work.2 Roller (2009: 1–2) notes that there is substantial evidence for the existence of deities other than the well-known Matar, usually referred to as the Phrygian ‘Mother’, but she is cautious to associate all rock-cut sanctuaries with Matar (see also Berndt-Ersöz 2006: 170–72 who suggested evidence for ‘the Male Superior God’).

Phrygian rock-cut monuments cluster in and around the Phrygian highlands bordered by the modern towns of Eskişehir, Kütahya and Afyon: this is a mountainous and verdant landscape whose valleys are watered by the meandering Sakarya (Sangarius) River and its tributary Porsuk (Tembris) around Türkmen Dağ. It is a region of (Tertiary Period) volcanic tuff resulting in high perpendicular outcrops of soft, easily workable bedrock, and valleys with rich alluvial soils such as the archaeologically well-known Göynüş (Köhnüş) valley. It is frequently pointed out that Matar’s association with mountains and rocky landscapes may be evident in her epithet ‘kubileya’, suggested to denote ‘a natural feature of the landscape, probably a mountain’ or a specific mountain (Roller 1999: 68; Berndt-Ersöz 2006: 83; Işık 2008: 40–47, with refs.). The epithet kubileya appears twice: once on a step monument in the Köhnüş valley in the Phrygian highlands (Berndt-Ersöz 2006: cat. no. 56; Brixhe and Lejeune 1984: inscription W-04), and once on an inscription right next to a triangular rock-cut niche at Germanos (Soğukçam)/Türbe Önü-Yazılıkaya, 26 km south of Göynük in Bithynia (Berndt-Ersöz 2006: cat. no. 40; Brixhe and Lejeune 1984: inscription B-01). Vasilieva (2001: 53) points out that: ‘according to one linguistic hypothesis, matar kubileya of these Old Phrygian inscriptions is an exact equation of meter oreia, i.e. the epithet had not been derived from the name of a certain mountain, but just from the word for mountain – her privileged dwelling’. In consultation with Old Phrygian as well as Greek literary and archaeological evidence, Vassileva (2001: 53, with ref. to Zgusta 1982: 171–72) has aptly summarised this association: ‘Kybele is the mountain that bears a cave, either natural or artificial’.

Phrygian rock-cut monuments are usually discussed as open-air sanctuaries involving cult façades and niches, stepped monuments with thrones, aniconic idols and altars, and sometimes even tombs and wine presses (Haspels 1971). Yet, our knowledge of the function and meaning of these monuments, features and sites is relatively meagre despite the growing amount of archaeological work on them (for various readings of the monuments, see Vassileva 2001; Berndt-Ersöz 2009: 11, 143–205). The great majority of the monuments are uninscribed and aniconic, especially those dated to the early Iron Age, whereas only with the Middle Phrygian period (800–550 BC) do we begin to see inscribed monuments and figurative representations of Matar (Berndt-Ersöz 2006: 142). The choice of rocky landscapes and hilltops, locations with impressive vistas, and the environs of springs and rivers for these monuments suggest that this was a ubiquitous place-making practice in extra-urban contexts in Phrygian Anatolia at this time.

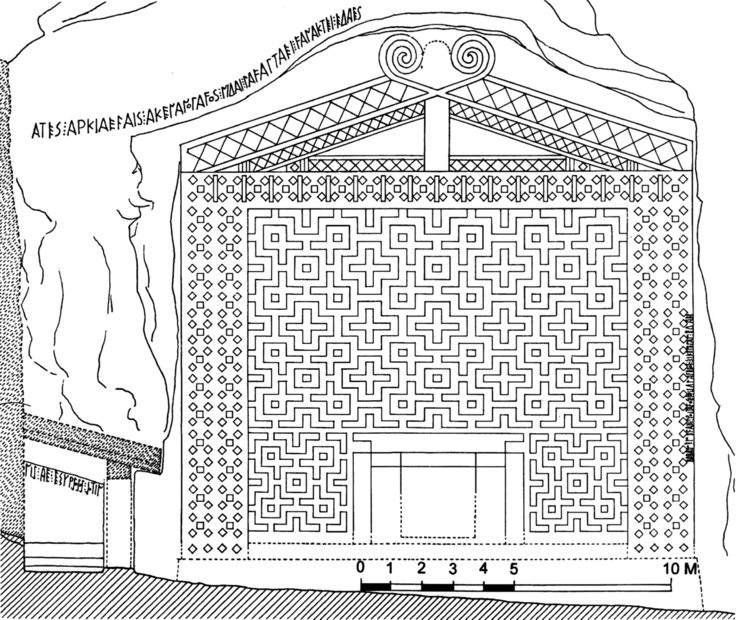

The three major rock-cut Phrygian sites – Dümrek, Fındık and Midas City (Yazılıkaya) – offer a complex variety of rock façades with niches and step monuments with culminating thrones or crescent-shaped discs as backrests. Among these, the evidence for cultic activity at Dümrek, 40 km northwest of Gordion and overlooking the Sakarya River, is considered the earliest, because of its overwhelming Early Phrygian pottery assemblage (Grave et al. 2005; Berndt-Ersöz 2009: 12). At Dümrek, on the one hand, one finds a fascinating clustering of about 15 rock-cut step monuments of various sizes (Berndt-Ersöz 2006: cat. nos. 101–107). On the other hand, Midas City as a sacred landscape offers a wealth of elaborately carved rock-cut façades, such as the so-called Midas Monument (Figure 22.10), the Areyastis Monument (Hasan Bey Kaya) or the ‘Broken Monument’.

Figure 22.10. Phrygian ‘Midas Monument’ at Yazılıkaya/Midas City, from Berndt-Ersöz (2006: fig. 50).

The designs are composed of an architectural façade with a pediment and acroteria, a framed surface reminiscent of a substantial post-and-lintel system, a central door-like niche and dazzling geometric patterns on all surfaces. Many of the façades have flattened, semi-enclosed, open-air platforms and subsidiary architectural spaces in front of them, possibly for specific ritual gatherings. Certain rock-cut monuments of the façade type, located in different valleys, have associated with them deep vertical shafts descending from the top surface of the bedrock behind the façade, and connecting horizontally to the niche in the bottom through a small window opening. Some scholars have associated the shaft monuments with oracular activities and communication with the world of ancestors (Özkaya 1997; Berndt-Ersöz 1998). The shaft monuments are rather broadly distributed and built away from each other: Maltaş in the Göynüş valley, Bakşeyiş/Bahşış Monument in Kümbet Valley, Değirmen Yeri in Karababa Valley, Delikli Taş near Tavşanlı and Fındık Asar Kaya northeast of Kütahya.

The political aspect of rock carving is apparent at sites such as Midas city where several monumental rock-cut façades with spectacular architectural designs and iconographic language suggest Phrygian royal patronage. Rock-cut monuments are particularly powerful tools for political elites to appropriate and colonise sacred landscapes and holy places. Spectacular, almost dazzling designs of the Midas city monuments carved into the living rock at previously venerated sites of Matar’s divine epiphany bring political power and local cult practices together for the negotiation of cultural meanings and symbolisms of a place. Political discourse here uses ‘nature’ (specifically the bedrock that is holy to Matar) as a grounding of place, in a way perhaps annihilating traces of previous micro-practices. One has to be cautious, however, in seeing the cult(s) of Matar as a unifying, state-sponsored deity of politically (read ‘artificially’) elevated status, similar to the Assyrian ‘Aššur’ or Urartian ‘Haldi’, as there is little or no evidence to make such a suggestion (contra Roller 2009: 8, who writes ‘the patronage of the goddess by Phrygian rulers in the first half of the first millennium BC gave the Mother unusual prominence as a symbol of Phrygian culture…’).

Rock-cut tombs are not unknown in Phrygia either, although oddly enough they seem to be excluded consistently from the study of Phrygian rock-cut monuments (e.g. Berndt-Ersöz 2006: 152–57). Finely decorated tomb monuments such as Aslantaş and Yılan Taş in the Göynüş valley are built facing the Göynüş Kale Fortress and in close association with other rock-cut monuments such as façades, cult niches, step monuments and smaller rock-cut tombs (see Berndt-Ersöz 2006: fig. 5 for a map of the Göynüş valley). The Aslantaş tomb is protected by ferocious rampant and couchant lions arranged on the tomb façade in relief around a central flat ‘pillar’ (Johnson 2010: 227–28). The nearby shaft monument and elaborately carved façade known as Maltaş, to the south of the two monumental tombs, was built immediately above a spring (Berndt-Ersöz 2006: cat. no. 24, fig. 33; Johnson 2010: 230–31). The Maltaş monument has an inscription under the lintel of its doorway that reads ‘[s/he] dedicated [the ritual façade] to Pormates/Mater’ (e[daespormaptẹỵ]) (Johnson 2010: 231; Brixhe and Lejeune 1984: 47–49, no. W-05 a, b). Such a gathering of rock-cut features with various functions and a multiplicity of designs presents a complex landscape that cannot simply be explained with one practice or another. It is only possible to understand the place as a complex assemblage of rock-cutting practices that share a common semantic field associated with the cult of Matar, the creation and articulation of thresholds to the underworld and the world of the ancestors, and the powerful significations associated with the act of carving the living rock.

The continuity of the cult of Matar in the Late Iron Age, Hellenistic and Roman periods in the Phrygian highlands, at least at certain sites, is particularly important. At sites such as Kapıkaya near Pergamum, at Aizonai and at the Angdistis sanctuary in Midas City itself, the ritual practices associated with the Phrygian Matar seem to have been active; they had a special revival in the later first and second centuries AD, evident in multiple votive dedications and their associated inscriptions (Roller 2009: 6–7). Monumental rock-cut tombs with columnar and pedimented façades – such as the Gerdek Kaya monument in the Yazılıkaya-Midas Valley or the Kilise Mevkii tomb southwest of Eskişehir – continued to be built in Phrygia, particularly during the Hellenistic period, and were possibly affiliated with the Paphlagonian rock-cut tombs of the Achaemenid period (Tüfekçi Sivas and Sivas 2007: 58–60).

A common scholarly mistake about rock-cut monuments is the tendency to isolate each one as a solitary structure with a clearly definable, single and unchanging function and meaning associated with it. Such an approach typically fails to grasp the monument in its spatially and temporally situated, site-specific, historically nuanced context in relation to what is adjacent to it. As Vassileva (2001: 55) perceptively discussed, rock-cut landscapes are composed of complex places where several carved features and other structures are intimately linked through specific rituals, processions and a complex set of procedures involving the mountain setting and the water sources. Typological studies of rock-cut monuments unfortunately tend to dissect places into their features and components in meticulously prepared catalogues, where the coherence of culturally meaningful places is inevitably lost. I suggest that this approach must be replaced with what I term ‘an archaeology of place’, where understanding the complexity of places in a diachronic perspective is not sacrificed to the typological and chronological parsing of its constituents.3 This is almost a proposal to return to approaches such as that of Emilie Haspels, whose intimate engagement with the Phrygian Highlands in the years of 1937–39 and 1946–58 admirably stands closer to a place-oriented archaeology (see now Haspels 2009).

Burying the Dead

While we have increasingly rich literary and archaeological evidence for the close association of Hittite royal burial practices with rock-cut tombs and memorials (Van den Hout 2002), it is only during the Anatolian Iron Ages that the practice of burying the dead in rock-cut chambers became a widespread, inter-regional practice. Rock-cut tombs appear at this time as one of the many forms of burial, alongside other monumental funerary structures such as the tumulus or the tower tomb. Such tombs are prominently attested in Urartu in the Lake Van Basin and the Upper Euphrates valley (Işık 1995; Köroğlu 2008), in Paphlagonia and especially in the modern provinces of Kastamonu and Amasya (Johnson 2010), and in Lydia during the Late Iron Age. This practice seems to have spread throughout much of the limestone landscapes of southern Anatolia, particularly Lycia, Cilicia and Caria in the Hellenistic and Roman periods (Işık 1995; Cormack 2004: 17).

In the Lake Van basin and the Upper Euphrates valley in eastern Anatolia, as well as broadly in Iranian Azerbaijan and the Transcaucasus, Urartian settlement landscapes of the eighth and seventh centuries BC feature a full flourishing of carving, inscribing and shaping the bedrock as a form of dwelling and building. Urartian fortresses are built on soaring rocky hills with major interventions made in the shape of the bedrock by creating stepped surfaces for constructing cut-stone masonry fortification walls, for making staircases, terraces and platforms, and for carving rupestral tombs and open-air sanctuaries as well as cuneiform inscriptions on the living rock. Rather than isolated monuments in the landscape, Urartian rock-cut architecture presents us with a complex worldview of building and dwelling.

Rock-cut tombs in Urartu are known from various citadels of the state, including its long-term capital city at Tušpa-Van Kalesi (on Urartian rock-cut shrines and tombs, see Forbes 1983: 100–13; Işık 1995; Çevik 2000; Köroğlu 2008). The royal tombs at Tušpa (‘Doğu Odaları’) were built in massive proportions, both in terms of the ceremonial platforms in front of them and the interior of the tomb chambers. Entry to the tomb chambers is gained through raised monumental entrances, accessed through rock-cut staircases and carved into very steep flattened façades. On the façade of the south/southwestern ‘Horhor Odaları’ tombs at Tušpa, a large commemorative inscription of Argišti I (Köroğlu 2008: 25) is somehow reminiscent of the Achaemenid royal tombs at Naqsh-i Rustam near Persepolis in the Fars province of Iran. Similarly, at the frontier fortress of Palu on the Euphrates, a large commemorative inscription of Menua on the very top of the fortress is accompanied by a series of rock-cut, multi-chamber tombs, while the Doğubeyazıt tomb features relief imagery (Forbes 1983: 104–105). The interiors of the tombs feature several niches for offerings and imitation structural members, such as roof beams shown in relief.

Thinking through such a broad and long-term perspective on the Anatolian peninsula, the rock-cut tombs of Achaemenid Paphlagonia present a fascinating case of places where local, Greek and satrapal Persian identities were negotiated through the practices of rock carving (Johnson 2010). During the Achaemenid period, Paphlagonian elites seem to have built a series of funerary monuments in the landscape closely associated with settlements. Iconographic analysis of the tombs that feature columnar temple façades with gabled roofs, and representations of Greek mythological subjects, as well as Achaemenid fabulous beings, suggest a complex hybridisation of visual culture in this mountainous region of the peninsula. The inheritance that this micro-regional development owes to the long-term technologies and practices of rock carving and place-making in the Anatolian peninsula is well balanced with the local innovations in rupestral funerary monuments.

Conclusion

In discussing the making of rock-cut monuments as a place-making practice, one has to be sceptical of the common modernist understanding of landscape and place. According to this view, landscape appears as an unaltered natural environment, a background or undifferentiated space into which ‘socially constructed’ places or ‘state-sponsored’ monuments are inserted. In this world view, places appear as islands or as clearly delineated ‘sites’, if you will. Here, I intended to critique this modernist notion of space as a noiseless, uniform background, and replace it with a complex notion of landscape, a rich topographical texture, infinitely differentiated, chaotic and continuously altered.

Landscapes are not measurable voids or vast open spaces, but rather form a hybrid product of natural and cultural processes that often mix into each other. Ontologies of places are such that specific geologies encounter and mix with material practices of the everyday, with cultures of worldly living. Communities that define themselves through a certain sense of belonging to a particular place exist by virtue of their specific social attachments, situated memory practices and local histories. The politics of space, spatiality and monumentality are juxtaposed with stories written and recounted about landscapes, and places are thus always already imagined and politically negotiated. Contrary to the modernist dissection of landscape into its discrete components of the natural, the cultural or the imagined, I argue for an understanding of landscape that is only possible at the intersection of all these. In the processes of place-making, that is, in the processes of making places as culturally significant locales (like Maalouf’s Ain el-Qabou,) what is important is the blending of the micro-geology of place with the cultures of place that are woven around it, and the stories told about it.

From the Late Bronze Age to the end of the Iron Age on the Anatolian peninsula, the practices of making commemorative rock reliefs and inscriptions, constructing open-air shrines and sanctuaries, and carving out rock-cut tombs have been an ever-evolving place-making technology that inscribed and re-articulated places. Contrary to the widespread scholarly understanding of Hittite rock-cut monuments as solely commemorative, and of Phrygian monuments as reflective only of ritual, I have tried to emphasise the coexistence of commemorative, cultic, funerary and political functions and meanings of rock-cut monuments over the long term. Thus, it may be suggested that the carving of a rock relief is in itself an innovative, transformative and especially performative act that in a way appropriates existing practices and significations associated with the locale. Through monumentalisation, it artfully clarifies and articulates the richness of the place while incorporating it into new networks of state discourse, preparing the ground for new meanings, practices, stories and negotiations.

Acknowledgements

I thank the editors of this volume for their continuous encouragement and patience.

1 See the Black Obelisk inscription belonging to the time of Shalmaneser III (Grayson 1996: 65). Similar events are depicted for the scenes usually identified as taking place at the Source of the Tigris (King 1915: relief panel 10; see Schachner 2007 on the Balawat Gates representations).