33 An Entangled Past: Island Interactions, Mortuary Practices and the Negotiation of Identities on Early Iron Age Cyprus

Abstract

This study is concerned with the Iron Age archaeology of Cyprus, from the end of the Late Bronze Age to the start of the Cypro-Archaic period, ca. 1200–700 BC. It treats thematic issues involving death, burial and identity, engaging certain theoretical perspectives with the large body of extant mortuary data, in order to explore the complexities of sociopolitical development on Cyprus during the Iron Age. Specifically, I consider how the material culture of mortuary practices was actively involved in the multiple social and spatial dynamics – maritime connections, migrations, colonial encounters and intra-island interactions – that occurred with the collapse of larger, regional palatial societies at the end of the Late Bronze Age, and the subsequent emergence of smaller, local hybridised polities involving native Cypriotes and incoming peoples from the Aegean and Levant during the Iron Age. Traditionally, Cyprus’s sociopolitical development during the Iron Age has been explained in terms of external stimuli, with particular focus on the Aegeans and the Phoenicians. This study, however, pays particular attention to the internal dynamics that helped transform the social and political trajectory of Cyprus during the Iron Age.

Introduction

The Cypro-Geometric period (CG; ca. 1100–700 BC) constitutes the formative years of the Cypriot Iron Age. As the transitional period between two distinct urban societies – the Late Bronze Age (LBA) and the Cypro-Archaic (CA) – the CG, or early Iron Age (EIA) (see Table 33.1), is central to understanding the long-term social and political development of the island. As Iacovou (2005b: 24) notes, ‘no time after the eleventh and the tenth centuries is more decisive for the island’s political development during the first millennium BC’. This chapter examines the sociopolitical trajectory of the island at that time, undertaking an analysis of the mortuary records of LBA Enkomi and EIA Salamis (Figure 33.1). I challenge the traditional argument that the island’s sociopolitical development was primarily the result of external intervention. Rather, I explore the notion that the eleventh century BC was a ‘time of intensive human movements in the eastern Mediterranean, when newcomers and natives on Cyprus transformed the island’s material and social practices’ (Voskos and Knapp 2008: 675).

Figure 33.1. Map of Cyprus, showing sites mentioned in text (Sarah Janes).

| Period | Periods | Years | Broad period classifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late Bronze Age | LBA | 1450–1100 BC | LBA |

| Proto-Geometric (traditional LC IIIB) | PG | 1100–1050 BC | EIA |

| Cypro-Geometric I | CG I | 1050–950 BC | |

| Cypro-Geometric II | CG II | 950–850 BC | |

| Cypro-Geometric III | CG III | 850–750 BC | |

| Cypro-Archaic | CA | 750–475 BC | MIA |

Until relatively recently, the EIA was largely overlooked due to a perceived lack of archaeological data for the period. This was because the data are almost entirely mortuary-based, and there was some reluctance to deal with complex burial remains. This issue was compounded by a long history of inconsistent excavation and recording techniques, and the varying quality of the resulting publications (fully discussed in Janes 2008: 29–31).

Furthermore, scholarship focused on the ethnicity of people who lived on the island at the start of the Iron Age and, consequently, there was a tendency to promote the notion of the ‘hellenisation’ of Cyprus, emphasising the role of Aegean peoples in the island’s sociopolitical developments. This assertion was largely based on the ascription of Greek ‘ethnicity’ to pottery, artefacts and innovations in the EIA archaeological record, many of which had Homeric associations in the eyes of the excavators (e.g. Mylonas 1948). Moreover, later fifth-century BC foundation legends were given the weight of historical fact (Iacovou 2005a: 126). When combined with the construction of what has been termed the ‘Hellenisation narrative’ of nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars (Leriou 2007), twentieth-century colonial archaeology (Given 1998) and nationalistic agendas (Knapp and Antoniadou 1998; Leriou 2007), people from the Aegean were assigned a pre-eminent role on the island during the EIA.

Over the last 30 years, however, research interests have shifted away from narratives based on the ‘ethnicity’ of individual artefacts and on later textual evidence to those focusing on processes of sociopolitical change (see, in particular, Rupp 1985; 1997; Iacovou and Michaelides 1999; Janes 2008). Moreover, with the creation of a database bringing coherence to the disparate records of the EIA mortuary landscape (Janes 2008), significant steps have been taken towards a more nuanced understanding of the long-term history of LBA–EIA Cyprus.

Mediterranean Upheavals: Thirteenth–Eleventh Centuries BC

Situated on major routes of commerce and interaction, Cyprus played a central role in trade, exchange and the movement of ideas, materials and traditions across the Mediterranean throughout antiquity. By the thirteenth century BC, a series of thriving, urban centres had emerged along the coast of Cyprus, and the island had become a key player in international trade, largely as a result of the island’s rich and desirable copper resources. Thus, when the major states of the LBA eastern Mediterranean – including the Mycenaean palatial systems and Levantine centres such as Ras Ibn Hani and Ugarit (Karageorghis 1987: 117; 1992: 81; Rupp 1987: 147) – suffered a severe social and economic collapse during the late thirteenth century BC, the island did not go unaffected (Iacovou 1998: 334–35). During the twelfth century BC, Cyprus entered a period of uncertainty and urban disruption, evidenced by the abandonment and destruction at many LBA sites. These disruptions, however, were neither long lasting nor severe, and there is significant evidence of sociopolitical continuity across this period (Snodgrass 1994). In particular, the sites of Palaepaphos and Kition exhibit evidence for continuous habitation across the LBA–EIA transition, and the construction of monumental sanctuaries at that time suggests the presence of prosperous strong and centralised authorities (Webb 1999: 292; Iacovou 2006b: 326).

At the start of the eleventh century BC, following this period of population movement and social unrest, a new sociopolitical landscape began to emerge, and Cyprus embraced a social and material diversity that reflected the hybridity of the island’s EIA population (Knapp 2009: 231). The collapse of the Mediterranean states in the thirteenth century BC resulted in increased and diversified movements of groups and communities, travelling along new or established routes in a Mediterranean that found itself temporarily free from state rule (Iacovou 2006a: 33–34). The eleventh-century BC horizon on Cyprus reflects the complex meeting and mixing of people and cultures stimulated by the prevailing socio-economic conditions. By the time the Neo-Assyrian state emerged on the nearby mainland in the eighth century BC, the Mediterranean had been free from outside rule for four centuries, and it was within this ‘power vacuum’ (Iacovou 2002: 84) that the territorial polities of CA Cyprus became fully established (Iacovou 2002: 83–84; see also Stylianou 1989: 379–82).

Reconstructions of the island’s sociopolitical trajectory from the thirteenth to the eighth centuries BC have focused on external influences as the primary stimuli of (secondary) state-formation – in particular from Aegean peoples during the twelfth–eleventh centuries BC, and the Phoenicians during the ninth century BC (for summaries of the main arguments, see Leriou 2007; Knapp 2008: 281–97). As Knapp and van Dommelen (2010: 13) note, however, focusing on the impact of external forces ‘precludes any attempt to consider how enduring factors such as mobility, contact, conflict and co-presence influenced and underlay local people’s cultural and social practices’. It is not disputed that people from the Aegean and the Levantine coast were part of the multiple social and spatial dynamics of the EIA that helped to shape the sociopolitical trajectory of the island. Moreover, despite the tenuous nature of the evidence for a predominantly Greek influence on EIA culture, it is clear that by the Cypro-Classical period ‘certain elements of the Cypriot population chose to define themselves as Greek’ (Steel 2008: 156; see also Iacovou 1999). The Aegeans and the Phoenicians had been part of ongoing ‘conversations’ with the island since the LBA (Voskos and Knapp 2008: 661). Traditional interpretations, however, discuss the impact of these external forces in terms of ‘decisive episodes’ (Iacovou 2008: 244), erroneously categorising homogenous communities whose impact on the island was administered in short event horizons, whilst the situation was undoubtedly far more complex. As Vanschoonwinkel (2006: 103) notes, ‘Greek penetration [of Cyprus] was a lengthy and complex process’.

Recent scholarship has turned to the dynamics of sociopolitical interaction on Cyprus during the EIA, examining the extant data more thoroughly and providing more nuanced studies of the island’s development (Janes 2008; Blackwell 2010). This chapter is concerned with how the Archaic city-kingdoms emerged, how people and cultures engaged with each other on Cyprus within the dynamic and changing world of the eleventh century BC, and how they negotiated their roles within and beyond the island community.

Identity and Sociopolitical Change in the Mortuary Record

The ways in which people identify themselves within the world are increasingly better explored and documented (see, e.g., Jones 1997; Diaz-Andreu et al. 2005). As Knapp and van Dommelen (2010: 4) note, identity is ‘a transitory, even unstable relation of difference’, an elaborate, multifaceted and dynamic social construct. Projections of identity are manifest at times of social contact as groups and individuals, consciously or subconsciously, try to establish their relationship within some specific form of interaction. Identity is dynamic; it fluctuates in response to social or political stimuli and is constantly being redefined in an effort to maintain some distinction between ‘self’ and ‘other’ (Knapp 2001: 32–33, 38). Mortuary data represent the material remains of actions performed in a specific arena of social contact. In the context of LBA and EIA Cyprus, careful examination of identity within the mortuary record enables us to explore how different groups negotiated their identities in the light of multiple and diverse cultural contacts, and to gain insight into various social interactions.

After death, when a person is physically removed from their place within the community, there is often a heightened awareness of identity as roles and hierarchies are renegotiated (Keswani 2004: 1; see also Manning 1998: 40). Whilst mortuary behaviour is largely shaped by and reflects human responses to grief and bereavement (Cavanagh and Mee 1998; Tarlow 1999; various papers in Tarlow and Nilsson Stutz 2013), it also provides a means of controlling the threat death makes to the continuation of society (Manning 1998). Burials provide the living with an opportunity to enact, physically and symbolically, the renegotiation of personal and social identities, helping them to create or maintain social and political control through ‘display, self-promotion and the transference of rights and positions’ (Keswani 1989: 20; 2004: 1; Murphy 1998: 32, 36–38; Voutsaki 1998: 41). Periods of relative social and political stability are often reflected by patterns in mortuary behaviour and gradually shifting symbolic and material markers of identity (Janes 2008: 250). Sudden and dramatic changes may point to physical expressions of competition, display and hierarchy (Manning 1998: 40), indicating moments of instability as groups or individuals feel pressured to ‘mark themselves off’ from neighbours and/or rivals (Hodder 1982: 186–90).

Engaging with the vast corpus of EIA Cypriot mortuary data, I turn now to examine how external and internal connections were entangled, how the dynamics of these entanglements were reflected in negotiations of identity manifest in mortuary behaviour, and how the material culture of mortuary practices was actively involved in the sociopolitical development of the island.

The Mortuary Landscape of Cyprus’s East Coast

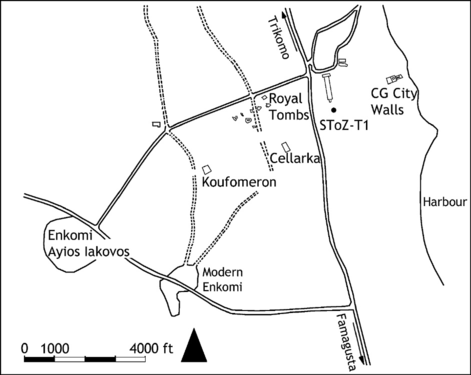

Three sites form the focus of emphasis in this chapter: Enkomi, Salamis and Palaepaphos. Around 180 tombs and ‘mortuary features’ have been excavated at Enkomi by various expeditions since the start of the twentieth century. These data vary in quality and, unfortunately, the stratigraphy and chronology often lack coherence (Ionas 1984; Keswani 2004: table 3.2). Here, I focus on the burial area of Ayios Iakovos inside the walls of the LBA city of Enkomi (Figure 33.2); the majority of the data used stem from Keswani’s (2004) extensive study of LBA mortuary behaviour on Cyprus.

Figure 33.2. Plan showing burial areas at Enkomi and Salamis (after Karageorghis 1978: 2) (Sarah Janes).

At Salamis, there are eight known excavated burial areas dating from CG I to the Roman period. The excavated tombs at Salamis have been relatively well recorded, particularly the Royal Tombs, Cellarka and Koufomeron (Janes 2008: ch. 6). This study focuses on the CG I burial just outside the city walls and the early burials at the Royal Tombs dating to CG III/CA I (Table 33.2 and Figure 33.2).

| LBA | LC IIIB/PG | CG I | CG II | CG III | CA I | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1200–1100 | 1100–1050 | 1050–950 | 950–850 | 850–700 | 700–600 | |

| Salamis Temple of Zeus | 1 | |||||

| Salamis Royal Tombs | 5 | 9 | ||||

| Salamis Cellarka | 5 | |||||

| Palaepaphos Eliomylia | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Palaepaphos Skales | 3 | 33 | 23 | 32 | 11 | |

| Palaepaphos Plakes | 13 | 8 | 12 | 3 | ||

| Palaepaphos Kato Alonia | 1 |

There are 23 burial areas across Palaepaphos, only 13 of which have been recorded in sufficient detail to form part of any analysis. Despite the fragmentary nature of all the data from Palaepaphos, they provide clear insights into mortuary practices from the LBA to the CA. Here, I focus on the LBA intramural burial areas, the CG–CA burials at Palaepaphos Skales and Plakes, and the CA burials of Palaepaphos Kato Alonia and Eliomylia (Table 33.2 and see Figure 33.5 below) (Janes 2008: ch. 4).

Figure 33.5. Map of the Palaepaphos area, detailing the spatial distribution of Cypro-Geometric and Cypro-Archaic sites discussed in the text (after Bezzola 2004: map 1) (Sarah Janes).

Changing Identities and Sociopolitical Development on the East Coast of Cyprus

Site Overview and Timeline

Enkomi was an established, and perhaps the dominant, economic and political force on the island during much of the LBA. Discussions concerning the exact role Enkomi played on the island at that time are manifold (summarised in Knapp 2008: 336–37; 2013: 433–37). For the present analysis, it is important to note that the town was extensively involved in international trade throughout the LBA, with distinct evidence for increasing interactions throughout the eastern Mediterranean (Steel 2004a: 155; Crewe 2007).

At the start of the eleventh century BC, there was a deliberate shift in settlement from Enkomi to Salamis, approximately 3 km to the northwest. The main impetus for this shift was most likely the silting up of Enkomi’s harbour, combined with the draw of the large natural harbour at Salamis to the north and the potential for the continuing exploitation of existing trade links (Lagarce 1993: 91). This settlement shift was a relatively gradual process, indicated by continued activity in the Sanctuary of the Ingot God at Enkomi for several years after Salamis had been founded, and by the presence of eleventh-century BC pottery across the Bronze Age site (Iacovou 1998: 810; 2005a: 131; see also Karageorghis 1969: 22).

Until the seventh century AD, Salamis was the pre-eminent town on the east coast of Cyprus (Iacovou 2005b: 25). Limited soundings and pottery scatters indicate a high level of urban organisation from the eleventh century BC onwards, including a defensive wall, roads, houses, a sanctuary and burials (Iacovou 2005b: 26; see also Yon 1980: 18; 1999: 17). There is also evidence for urban features, including organised religion in the form of worship to a male deity (Iacovou 2005b: 26; see also Yon 1993: 144, fig. 4); local craft specialisation in pottery and other artefacts, including bronze and iron items and Levantine and Aegean style jewellery (Yon 1971; 1999: 19); and trade in the form of imported metals and foreign pottery types (Iacovou 2005b: 26). The continued presence of competitive elite descent groups at CG I and CG II Salamis suggests that the settlement was not a fully formed state at this time (Iacovou 2005b: 34).

During the CG period, internal and external connections developed and changed in response to continued upheavals across the Mediterranean, not least of which was the struggle for power in the east and the rise of the Assyrian state. Salamis’s geographical position on the east coast helped to promote Cyprus’s key role in international relations during the Iron Age, just as Enkomi’s had done during the LBA. Interpretations of Cyprus’s role in the Near Eastern sphere have, again, focused on the impact of external peoples on the island, neglecting intra-island dynamics. It is generally believed that the Phoenicians founded a trading post at Kition during the ninth century BC. This foundation was likely in response to Neo-Hittite and Aramaean princes taking control in the Levant during the ninth–eighth centuries BC, curbing Assyrian domination, blocking Phoenician access to the east and forcing their westward expansion (Bikai 1989: 205–207). It has been suggested that this ‘colonisation’ stimulated the creation of Cypriot elite-controlled trading ventures, and that the Archaic-period city kingdoms were formed ‘under the pressure of economic contacts and exploitation from an existing state’ (Rupp 1987: 154–55; 1998: 217). Once again, much of the evidence centres on the perceived ‘ethnicity’ of certain aspects of the material data – in this case, the presence of certain ‘temples’ dedicated at Kition to the Semitic deities Astarte and Melqart (Coldstream 1985: 51–53; see also Karageorghis 1982: 123).

Debate has also centred on the nature of the Assyrian relationship with Cyprus at the start of the Archaic period (see Knapp 2008: 341–47). The use of Near Eastern iconography and burial practices in mortuary contexts at Salamis from CG III has previously been used to support the suggestion of Assyrian domination over the island. Accordingly, the mortuary practices of the Cypriot ruling class are seen to emulate and imitate their Assyrian monarchs and other powerful neighbours (Reyes 1994: 63). The impact on the island of the power struggles to the east is far more complex than these interpretations suggest. The symbols, artefacts and practices employed in eighth-century BC burials at Salamis were adopted and adapted by the Salaminian ruling line to create a new hybridised ideology that suited their own needs, borrowing from a vast array of materials and practices available to them from the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean and beyond.

A Period of Change: The LBA–EIA Transition

The end of the LBA at Enkomi (LC IIC/LC IIIA) was a time when the site enjoyed its ‘greatest archaeological visibility’, yet there is still no consensus about its sociopolitical organisation (Crewe 2007: 11). Evidence from the mortuary record suggests that competition for control was based around elite group and kinship ties, what Keswani (2004: 85) terms a ‘heterarchical pattern of local hegemony’.

Throughout the LBA, a discrete section of the community was buried in built chamber tombs within the city walls (Ayios Iakovos; Figure 33.3), whilst the majority of people appear to have been buried extramurally under a ridge to the north of the city (Crewe 2004: 31). The intramural tombs were often placed under buildings and in courtyards, sometimes in boundary places such as doorways or passages. They were reused several times over many generations and there is evidence for restricted access or what Fisher (2009: 189–90; this volume) terms ‘private-exclusive’ rituals. Some of the built tombs appear to have been deliberately destroyed, sealed and emptied (in Dikaios’s Areas I and III), whilst contemporary tombs in the area remained in use (Crewe 2004: 33–38).

Figure 33.3. Late Bronze Age intramural built tomb at Enkomi (photo by Sarah Janes).

These built tombs were those of the elite, kinship groups who used mortuary behaviour as one method of negotiating their position within the social and political hierarchies of Enkomi. Through the manipulation of mortuary behaviour, they emphasised the power and legitimacy of their ancestral lines and created and maintained interfamilial competition (Crewe 2004: 37–38; Keswani 2004: 158–59; Fisher 2007: 288). Different aspects of mortuary behaviour played different roles in these ongoing negotiations. For example, the use of intramural, built tombs and private-exclusive rituals served to emphasise social differentiation between the elite and the rest of the community. Restricted access rituals also sent a clear message to other elite groups, depending upon whether or not they were included in the observances. The deliberate positioning of built tombs inside the walls, under houses and in liminal positions helped to establish power inequalities, playing out the complex negotiation of social boundaries (Fisher 2007: 289) through the use of physical ones (Keswani 2004: 87). The multiple reuse of tombs would have helped to establish a group’s legitimacy within the wider community through their ancestral links, and the destruction of other elite tombs would have sent strong messages about each group’s control and supremacy at any given time.

During the final phase of the LBA (Late Cypriot IIIA), there was a significant addition to the burial traditions of Enkomi – intramural shallow pit or shaft graves (e.g. tombs 13, 15 and 16; see Schaeffer 1936). Whilst a small number of elite built tombs continued to be constructed and some original tombs were reused, this new tomb type became increasingly popular (Keswani 2004: 97). The quantity of shaft tombs was relatively low – only 28 burials in all (Keswani 2004: 97) – indicating that this was not a new form of burial for the majority of the population. Significantly, unlike the chamber tombs, the shaft tombs contained only one to three burials, perhaps indicating a move away from the promotion of ancestral or kinship lines towards smaller group identities. It is significant that despite these seminal differences, some of the LBA shaft tombs contained a range and character of goods similar to those deposited in the built tombs. Major changes to traditional mortuary practices, such as the use of new architectural styles, can be a decisive statement about the identity of the people being buried, the people burying them and their perceived or desired positions within the community. Contemporary use of different tomb types within a single burial area may reflect group differentiation (see, e.g., Georganas 2002), and the spatial arrangement of tombs may signify the tolerance or otherwise between different groups (Cavanagh and Mee 1998: 108; Voutsaki 1998: 42–43).

There are many potential explanations for the appearance of these new burial practices at LC IIIA Enkomi. Possibly they belonged to people from other areas of the island who settled at Enkomi, drawn to the town by its increasing prosperity but lacking kinship associations that might be reflected in their burial practices (Keswani 2004: 97–98; Crewe 2007: 25). If this were the case, the similarities in tomb goods to those of the built tombs, and the placement of the new burial type within the city walls, may indicate that the newcomers adopted some aspects of established burial practices into their own traditions to help position themselves within the existing social hierarchy.

Alternatively, burials at Enkomi may have taken on a new or reduced role in sociopolitical negotiations at the end of the LBA/start of the EIA. Funerary ritual is by no means representative of all social practices at any given time (Barrett 1988: 30; Keswani 1989: 27; Cohen 2005: 1). At LBA Enkomi, other settings, including the emergent court and temple institutions, were becoming important arenas for social interaction (Keswani 2004: 143–44). Similarities in burial goods in both tomb types, and the apparent lack of competition over elite-only intramural burial space, suggest that the same elements of society were represented in these new tombs. The tomb architecture of existing elite burials may have become less labour intensive, catering to smaller family groups, as kinship ties began to be promoted in different arenas of social interaction.

The EIA at Salamis

Towards the end of the LBA, a new, ‘entrepreneurial’ society began to emerge along Cyprus’s east coast. New and renewed internal and external connections led to an increase in competition between elite groups for trade links, profitable connections and local resources, such as the metal sources at Tamassos (Iacovou 2002: 79; Steel 2004a: 170), or perhaps those near Palaepaphos (Iacovou 2012). The power of elite groups began to change as the geographical, social and political landscapes shifted; this is reflected in new, hybridised burial practices at CG I Salamis. There are limited burial contexts for the early occupation at Salamis in CG I – only tomb SToZ-T1 has been fully excavated and recorded (Yon 1971) (see Figure 33.4) – yet the extant remains for this period provide crucial insights into the sociopolitical landscape.

Figure 33.4. Plan of tomb SToZ-T1 under a Roman building, illustrating how the early tombs were built over by the expanding city (after Yon 1971: pl. 4) (Sarah Janes).

SToZ-TI contains a single interment accompanied by 30 items of precious metal, including jewellery, toilet items, decorative ornaments and a golden scarab. Bronze and iron weapons and a plethora of seals and amulets in various materials also contributed to the conspicuous wealth of this tomb (Yon 1971). This tomb illustrates well the diverse influences to be seen at Salamis in the eleventh century BC – from the Aegean, the Levant and Egypt. The deposition of more than 70 cups in the burial suggests that a large group of individuals was involved in the funeral itself, likely in the context of drinking rituals. This is further attested by an amphoroid krater and a vase support. The presence of cooking wares in the burial assemblage may indicate the preparation of food for feasting activities either at the tomb or in another setting nearby.

The tomb assemblage of SToZ-T1 was of a similar character to the burial goods in both the built tombs and in the shallow pit graves from LBA burials at Enkomi Ayios Iakovos (Keswani 2004: 124–29; Janes 2008: 307–308), indicating some level of continuity between the population buried at Enkomi and those interred at CG Salamis. This tomb most likely represents the move of a distinct elite kinship group from one town to the other (Janes 2008: 307). Whilst the character of the assemblages was similar, however, the goods were significantly richer and the mortuary rituals more inclusive at Salamis. Furthermore, this burial was extramural (placed just outside the city walls) in a new tomb construction – the chamber and dromos tomb (with an entrance or literally ‘road’ into the tomb). The similarities and differences between this tomb and the LBA Enkomi burials were undoubtedly intentional, carefully chosen to promote different aspects of identity as elites adapted to the new spirit of entrepreneurial competition.

The new tomb type and extramural burial areas were an island-wide phenomenon in the CG period. Their significance, whilst largely elusive, appears to have varied between regions (Janes 2008: 326); at Salamis, the burying group used these new developments to their own advantage. Burial outside the town would have necessitated the movement of the body, perhaps involving a procession, affording the opportunity to showcase the burial assemblage. Hereditary links to the LBA town were deliberately referenced in the choice of burial goods deposited in the CG I tomb in an attempt to legitimise their new, sociopolitical position.

Death rituals afford people the chance to contest offices and materialise ideologies whether they are the ruling or non-ruling group (Cohen 2005: 19). Rituals involving the consumption of food and drink can be particularly powerful (Hamilakis 1998; 1999; this volume; Steel 2002: 110; 2004b: 281); eating and drinking involve ‘emotions, pleasures and feelings’ (Hamilakis 1999: 39) and act as powerful mnemonic devices (Hamilakis 1998: 122, 128; 1999: 40; this volume). The inclusion of more members of the community in mortuary observances indicates that mortuary practices played a significant role in elite power politics as competition for local resources and overseas trade links intensified; these new practices would have helped to establish a new frame of reference on which the social history of the community could be built.

Emergence of a City-Kingdom: Creation of an Ideology, Hybridised Burial Practices

In CG III, competition for control over the island’s resources and profitable trade links reached a climax. The wealth and power of Salamis became firmly established in the hands of a small number of individuals within a new ruling lineage (Janes 2008: 309). This moment reflects the decisive move away from kinship power politics into a centralised institution of rule, and can be considered the moment that the city-kingdom of Salamis was fully established. At this time, a new monumental burial area, which held the so-called Royal Tombs, was established on the flat plateau to the west of the town. All aspects of these tombs and the rituals associated with them were designed to legitimise the pre-eminence of the dominant ruling power. The burials played a central role in the materialisation of a new ideology, every aspect designed to promote messages to locals, foreigners and people from across the island. Of these messages, the most significant are the explicit statements of power and control aimed at other elite groups within and beyond the town, and at Salamis’s powerful neighbours: this new city-kingdom was a serious international player in the ever-intensifying trading spheres of the eastern Mediterranean.

The Royal Tombs were stone-built monumental chamber and dromos constructions. Each tomb had a large dromos leading to a relatively small chamber in front of which many of the tombs had a deliberately elevated ritual area, e.g. SRT-T47. Intensive looting at the site affected many of the tomb chambers, and as a result, most data for the Royal Tombs come from dromos assemblages (Karageorghis 1969: 50). Evidence for ritual activities around the tombs is extensive, from the size of the dromos – which likely provided a viewing platform at the funeral – to the goods deposited within it. Each dromos contained an overwhelming quantity of artefacts including wooden furniture, metal items including giant cauldrons and obeloi (iron spits), and a large number of pottery vessels. The most prolific artefacts were bowls, deposited in the hundreds in each dromos. The dromos of SRT-T79, for example, contained 150 bowls and dishes of different sizes, some containing chicken bones, fish bones or eggshells (Karageorghis 1969: 97). Jugs, jars and amphorae also featured heavily, along with other pottery vessels often deposited in large quantities, e.g. 46 basins in the CG III dromos context of SRT-T79. All the dromoi of these earliest Royal Tombs contained evidence of horse sacrifices, including skeletons and horse and chariot trappings.

The distance of the burial area from the town would have necessitated a long funerary procession; this was a strategic step towards the creation of a powerful new funerary ideology. Mortuary processions provide an arena for overt conspicuous display and can create a highly charged environment. The wealth of goods in the dromoi and the array of chamber goods recovered from the tombs suggest that the adornment of the body and the quantity and quality of artefacts would have allowed pre-eminent members of Salaminian society to assert their power, wealth and influence through extraordinary visual and audible displays. Furthermore, the procession may well have involved a large proportion of the Salaminian population, as well as visitors and emissaries from other parts of the island and from overseas. The capacity of the funeral to motivate such a large group of people attests to the power and influence of the ruling line (Huntington and Metcalf 1979: 139; Keswani 2004: 9).

Monumental stone tombs of this size had not been seen on the island previously. Their size as well as their permanence and strategic position on the landscape ensured that they were highly visible to local inhabitants, to visitors from across the island who would pass through or by the tombs to enter the town, and to foreigners who would have seen the magnificent monuments on the horizon as they approached the harbour. The position and design of the tombs ensured that they, and the ideology associated with them, would have been communicated across both distance and time (for discussion of similar burials at Ur, see Cohen 2005: 14).

With small chambers, large dromoi and elevated platforms, the tombs were designed to accommodate a host of mortuary practices and to provide a viewing platform from which these could be observed (Rupp 1988: 122). The vessels found in the dromoi indicate that there was a large element of personal participation in the funerals, probably involving the consumption of food and drink, the offering of gifts and theatrical, emotive displays including the stoning of animals that had been part of the funeral procession (Janes 2008: 258–74, 314–17). Large-scale feasting and drinking in a mortuary context is a powerful instrument for the construction of social identities and for establishing community cohesion by creating bonds of friendship or obligation (Steel 2004b: 281; Blake 2005: 107). Such rituals can also be used to emphasise social differentiation by associating particular ritual actions with the group or individual providing the feast (Fisher 2007: 266–67). Through the use of communal feasting and drinking, the Salaminian ruling line would have imbued the tombs with power and wealth, creating the impression of communality whilst also marking boundaries. Social hierarchies would have been re-emphasised through the uneven distribution of food or the consumption of different foodstuffs (Blake 2005: 106–107), at the same time creating debts of duty or obligation through their generosity and the provision of ‘embodied pleasure’ (Blake 2005: 107; see also Hamilakis 1999: 40; Steel 2004b: 283).

The practices, vessels, materials, iconography and other artefacts in the dromoi of these tombs demonstrate the extremely diverse range of influences the Salaminian ruling line adopted into their burial repertoire. Wooden furniture inlaid with ivory reflects Assyrian, Syrian and Phoenician influences. Bronze bowls, ivories and terracotta candelabra are all part of the Assyrian repertoire, as seen at Nimrud (Mallowan 1978; Reyes 1994: 63). Horse sacrifices imitate rituals from elite Assyrian burials and also have precedence in tombs at Marathon, Nauplia and Argos in Greece, Osmankayasi and Gordion in Anatolia, and elsewhere (Karageorghis 1965; 1967: 17). Jewellery, such as diadems and mouthpieces, and their iconography, including lions and sphinxes, show notable Near Eastern inspiration. Scarabs, seals and amulets represent a distinct Egyptian influence, and, finally, Aegean pottery and burial practices were included in the Salaminian burial repertoire, including cremation and offering pyres (Janes 2008: ch. 6). All of these elements were adopted and adapted to help represent the ruling lineage at Salamis as they wished to be perceived. The wealth deposited in the Royal Tombs emphasised that the Salaminian rulers had as much disposable wealth as did their powerful neighbours (Karageorghis 1969: 14) at a time when ‘state-controlled markets’ (Iacovou 2005b: 27; 2006b: 317–18; see also Rupp 1988: 111) emerged in the Near East. These burials were ‘an assertion of … pride, dignity and equality’ (Karageorghis 1969: 14–16; Rupp 1988: 112), particularly in relation to other polities operating in the same trading spheres at this time.

It is important to note, however, that it was not just foreign elements that were adopted into the hybridised burial practices of the Royal Tombs. It is evident that many practices employed by the CG III Salaminian ruling line had their origins in Cypriot practices – in particular, those observed in the LBA burials at Enkomi, such as drinking rituals. These rituals had already been adapted to suit the ideological needs of the CG town and were adapted further at the end of CG III to create a new frame of social reference with the ruling lineage at the centre; the rituals had developed in scale, in audience and in the messages they were intended to convey. By the end of the EIA, power inequalities between leading elites, as seen at Enkomi and during the early years at Salamis, had become power and wealth inequality between the ruling line and the rest of the community; in this development, the creation of a new burial ideology had played a central role.

Regionalism and Cross-Island Hybridisation

I have demonstrated the complex interactions underway at Salamis at the start of the IA, exploring how the emergence of a city-kingdom was strongly influenced by the prevailing sociopolitical environment. Central to this is the awareness that sociopolitical development across the island was a direct result of unique connections between local, other island and non-island communities.

Unlike the turbulent mortuary record of Enkomi and Salamis, that of Palaepaphos illustrates a gradually shifting sociopolitical trajectory across the EIA. New architectural features were introduced, and there is evidence for the hybridisation of local and foreign materials and practices, as well as a shift from intra- to extramural burial areas. Yet the mortuary record reflects 350 years of gently fluctuating sociopolitical development (Janes 2008: 157). To explore this idea further, I consider the city-kingdom of Palaepaphos on the southwest coast, which emerged in response to different internal and external pressures.

Palaepaphos: The LBA–EIA Transition

Palaepaphos is one of only two towns on Cyprus with evidence for continued occupation across the LBA–EIA transition. Data for the LBA at Palaepaphos are fragmentary – around 53 tombs have been excavated and recorded, but a large quantity of this material was found in pits and dumps, the result of looting activities, intentional removal of items from their original contexts and other indeterminable disturbances (Catling 1968: 165; Janes 2008: ch. 4). Nonetheless it is possible to characterise LBA mortuary behaviour generally. The evidence for elite group competition at Palaepaphos in the LBA is similar to that of LBA Enkomi: tombs were placed within the settlement, some under domestic areas and some under workshops. Keswani (2004: 88) suggests that this was a response to interfamilial competition and a tactic employed to validate claims on workshop space. As at Enkomi, the Palaepaphian tombs were used to emphasise hereditary rights. In particular, they reflected inherited rights to the land (Manning 1993: 48) and emphasised the role of groups in the agricultural prosperity of the community – e.g. depositing ground stone tools and other functional items. The burial assemblages also point to rising specialisation, increasing overseas contacts and growing urban prosperity, demonstrated through the deposition of restricted items such as precious metals, e.g. gold and silver (tomb PPEv-T8), unusual goods such as the hippo and elephant ivories (tomb PPE-T119, and particularly the burials at Teratsoudhia; Karageorghis 1985: 909–11). Together, the range and quantity of items in these LBA burials formed a ‘distinct complement of status symbolism’ (Keswani 2004: 85). These symbols were carefully chosen to reflect the past, present and future in a form that enabled groups to engage in the complex social competition of the time (Manning 1998: 40).

During the CG period, burial areas at Palaepaphos became extramural (Figure 33.5). Palaepaphos Skales, Plakes, Xerolimni and Lakkos tou Skarnou are located at a considerable distance to the north, east, southeast and southwest of the main part of the site, reflecting a significant shift in the social landscape (Janes 2008: 146; see also Maier and Wartburg 1985: 152). The prominent positioning of the burial areas in boundary positions – inland as well as towards the sea – suggests that the Palaepaphian community was equally, if not more, concerned with intra-island tensions and a perceived threat from other islanders as they were with incomers from beyond the island. These boundary burial areas asserted a new, collective identity. In the EIA, therefore, distinct kinship and family groups came together in these collective burial areas; the requirement for a community bond transcended the importance of LBA interfamilial competition. This move resulted in the loss of an important means of social interaction and renegotiation of sociopolitical positions, weakening the power bases of the elite groups. By CG II, the community burying their dead in the collective burial areas were demonstrating ‘social and cultural proximity’ (Iacovou 2005a: 131) based upon family associations. This decrease in social differentiation paved the way for the emergence of a pre-eminent ruling group at the start of the CA period.

Palaepaphos: The Cypro-Archaic Period

At the start of the CA period in Palaepaphos, as at Salamis, we see the decisive shift to the city-kingdom. Unlike Salamis, however, Palaepaphos did not have a single lineage burial area or ‘royal’ necropolis (Iacovou 2005b: 34). Instead, burials were placed in old LBA funerary areas such as Eliomylia and new ones such as Kato Alonia.

The extramural CG burial area at Palaepaphos remained in use throughout the CA period; the need to convey a strong community identity to other islanders and outsiders endured. The people using the burial areas clearly posed no threat to the emerging ruling line; the remnants of the LBA competitive elite groups had been assimilated into a new collective identity between CG II and the CA period, becoming part of the ‘securely established, culturally homogeneous and … prosperous communities’ (Iacovou 2005a: 12). This was in contrast to the situation at Salamis where a physical and ideological break was instigated by the ruling lineage in the CA period. To the new rulers at Salamis, the old CG tombs represented a continued threat from powerful elite groups, and so they enforced a physical move of burial areas from the CG area outside the city walls to Cellarka and Koufomeron. The old CG burial areas were built over as the city expanded, thereby removing all links to the social and political organisation of the preceding period and creating a new framework of sociopolitical reference (Janes 2008: 317). The tomb assemblages at Cellarka in the CA and CC periods contained restricted pottery vessels and goods, reflecting a further enforced change in mortuary behaviour, and limiting the opportunities for sociopolitical negotiations of the old elite families (Janes 2008: 317–20).

At Palaepaphos, several distinctive burials can be identified as those who held positions of centralised power during the CA period (see Table 33.3). Three of these come from Eliomylia, and all were impressive, energy intensive burials. For example, the façade of tomb PPE-T125 had been carved, the stomion (entrance to the tomb) carefully dry-walled shut, the fill of the dromos sieved and sorted before being used, and the whole filled with extremely rich burial goods (Hadjisavvas 2001: 89–90). The positioning of these tombs within the LBA burial grounds harkened back to LBA ancestral roots. Similarly, the assemblages made reference to inherited land rights and agricultural prosperity, alluding to the resources on which the ruling line now based their power and pre-eminence in society. This was achieved through the deposition of heirloom objects such as ground stone tools, a practice seen in the LBA but one that had largely fallen out of the funerary repertoire at the start of the CG period.

| Tomb | Date | Dromos | Chamber |

|---|---|---|---|

| KA-T1/1962 | CAI (first burial) | Horse burial Sheep burial | • Pottery: jugs, bowls, amphorae, including one Ionian bowl, one Cycladic bowl • Weapons: including a bronze shield fragment, iron dagger, bronze strainer, two iron fire-dogs, two bronze horse frontals, iron horse bit • Jewellery: including three bronze fibulae, bronze bracelet, faience bead, blue paste scarab, thin sheet of gold |

| PPE-T125 | CAI | • Many silver items • Jewellery: including rock crystal beads • Household goods: including ground stone tools, bronze vessels, including a bowl, kylix, and tray; the bowl had inscription in the old Paphian syllabary, a piece of slag | |

| PPE-T8/PPE-T7 Goods combined because the tomb assemblages are jumbled together | CA | Teeth and bones suggesting a horse burial in PPE-T8 | • Bronze household goods: strainer, cauldron, bowl • Weapons: iron sword, iron knife, bronze knife, bronze helmet • Five iron horse bits, two iron rings |

The CA burials also absorbed elements of CG mortuary practices, particularly from the burials at Plakes (tombs PPPl-T146, PPPl-T142) which contained, among other things, obeloi, weapons, exotic gold jewellery, cremation burials and sheep sacrifices (Raptou 2000) (Table 33.3). There were also some ‘heirloom’ artefacts found in the Plakes tombs, including a figurine head and a trident, emphasising continuity with the LBA (Janes 2008: 113). The similarities between the burial assemblages at Plakes, Eliomylia and Kato Alonia are so striking that it may have been the CG II elite group buried at Plakes that managed to gain control of the major resources of the town in CG II/CG III, rising to pre-eminence in the CA period.

Furthermore, the tombs at Palaepaphos almost certainly reflect a detailed knowledge of the Royal Tombs at Salamis and their elaborate mortuary rituals. Many aspects had been adopted and adapted into the mortuary practices of the Palaepaphian ruling line to suit their own ideological needs, albeit on a significantly smaller scale. For example, the CA tombs at Palaepaphos were monumental, chamber and dromos constructions. There was community participation at the burials, and animals were buried in the dromoi. Despite the pomp and circumstance, however, the most significant element of Palaepaphian mortuary display in the CA period was the re-emphasis of the ruling line’s continuity with their LBA ancestors, legitimising their claims to power. The Salaminian ruling line, by contrast, deliberately destroyed any lingering connections to LBA and CG elite group competition.

Conclusion

The original intentions and meaning behind many aspects of funerary behaviour are difficult to ascertain. The symbolism and significance of specific mortuary practices remain largely elusive to modern scholars, existing as we do far beyond the spatial and temporal boundaries of the community within which these symbols were originally understood (Hall 1997; Parker Pearson 1999: 33). The erroneous assumption that only a small part of the funerary experience is identifiable in the record, and that mortuary data alone, without other contextual evidence, are insufficient for an analysis of social and political change, has been challenged. Close examination of the EIA mortuary record has revealed a vibrant period of dynamic social and political change. Mortuary practices at all sites on Cyprus were the product of their own unique entangled connections and social, political and economic situations. Shifting identities in the mortuary record of the EIA can truly highlight how people, materials and ideas came together and were transformed on the island of Cyprus, and how material culture played an active role in the renegotiation of island identities.