37 Cult Activities among Central and North Italian Protohistoric Communities

Abstract

One of the crucial points in any historical theory is the role of religion in society, which is generally seen from two fundamentally different points of view: the Marxist notion that ideology is completely dependent on socio-economic ‘structure’, and Émile Durkheim’s view that religion is the origin of every social institution. Marxist scholars such as Antonio Gramsci have subsequently focused on ideology in the creation of social structures, while others such as Marvin Harris have stressed the overwhelming role of economy in the creation of religious myths and taboos. Archaeology could provide the key for testing these views.

A good case study is that of cult activities between the Early Bronze and early Iron Ages (2300–700/500 BC) in central and northern Italy. From a primitive idea of religion whose typical expression is the use of caves as cult places (deeply embedded in the oldest prehistory), the communities of these regions shifted their beliefs towards an anthropomorphic religion, around the time that the funerary rite and model of ‘chiefdom-like’ society spread. When Early State social organisation came about around the end of the second and the beginning of the first millennium BC, civic religion with priests, temples and its paraphernalia stood out as a key transformation of society. In this chapter, I explore this complex social trajectory in order to try to detect the nodal points of the transformations of cult activities in the archaeological record of protohistoric central and northern Italy.

Introduction

What is the role of religion? The orthodox Marxist position is that religion (and ideology, as a whole) is a ‘superstructure’ and completely independent from economic and social structure. This idea was challenged by the French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1912), whose Les formes élementaires de la vie religieuse regards religion as, on the one hand, the main experience through which single individuals feel themselves part of a society and, on the other, the origin of any great institution.

‘Participation’ in the natural environment in one way or another as a key factor of religion in primitive societies is the leading concept that Lévy-Bruhl put forward in his work in the 1930s, suggesting a two-stage development from a ‘pre-religious phase’, without deities but with a rich mythology, to a ‘religious’ one, in which the venerated ancestors become gods, even if many characteristics of the previous phase survive (Carandini 2002). In the following years, the Marxist Antonio Gramsci compiled his notes in Fascist jails between 1929–1935, attempting a synthesis between the apparently incompatible points of view that ideology plays a crucial role in the creation of social structures (Gramsci 2007).

The same dialectic characterised the decades following WWII, from the theory espoused by Radcliffe-Brown (1952) that religion is a powerful tool of cohesion in primitive societies, to the structuralist idea that religion must be understood in a cognitive dimension (Bell 1997), and from the idea put forward by the French anthropologist Maurice Godelier (1977) that religion is only a fanciful reflection of the real world in people’s minds, to the ‘vulgar’ materialism of Marvin Harris (1977), who in his books emphasised the overwhelming role of the economy in the creation of religious myths and taboos.

In recent years, anthropological discussions have focused on concepts such as ‘performance’ and ‘agency’ and envisage rituals as creative strategies by which people shape their cultural and social environment. A key contribution is the typology of rituals elaborated by Catherine Bell, who also classified the main characteristics of ritual actions (formalism, traditionalism, invariance, rule-governance, sacral symbolism, performance; Bell 1992; 1997).

In prehistoric archaeology, the traditional idea is well expressed by the famous ‘Hawkes’ hierarchy’ of ‘an ascending scale of difficulty in interpreting archaeological data in terms of human activities ‘(Trigger 1989: 392) – which has ideology at the top.

A different opinion is held by Colin Renfrew (1985; 1994), whose ‘socio-archaeological’ approach proposed that cult activities may be recognised in the archaeological record on the basis of the unambiguous presence of two types of evidence: the persons who perform religious rituals, and the deities in honour of whom these rituals are performed. Richard Bradley (2003; 2005) has challenged this point of view by countering that ritual as ‘a social strategy of a distinctive kind’ (2005: 33–34) is not separate from other spheres of human activity, as is evident, for example, at protohistoric sanctuaries such as Acy-Romance, the structural characteristics of which fit perfectly in those of domestic architecture. He contended that ritual must be considered ‘one of the main processes that formed the archaeological record’ (Bradley 2005: 209).

Many theoretical contributions emphasise the dichotomy between ritual (action) and belief (religion), emphasising either the first concept in ‘behavioural’ studies or the second one in cognitive studies. In his synthesis of the ‘archaeology of religious ritual’, Lars Fogelin (2007) has recently proposed a sort of ‘exit strategy’ from entrenched opposition towards the study of symbols and the development of ethnoarcheological studies of ritual. In a recent seminar, Evangelos Kyriakidis (2007a; 2007b: 16) rightly stated that ‘ritual is a set of practice and that implies a relative constancy through time’ which is a characteristic that makes it recognisable in the archaeological record.

Renfrew (2007: 114) referred to the anthropologist Melford Spiro to define archaeology as ‘an institution consisting of culturally patterned interaction with culturally postulated superhuman beings’ and to draw attention to the ‘time dimensions’ of ritual (in the sense of the calendar, but also of the succeeding stages of human life). Renfrew also distinguishes religious ceremonies in state systems as characterised by a ‘civic’ dimension. In the conclusion to the seminar, Kyriakidis posed the crucial question of whether social structure conditions rituals or vice versa. The answer is halfway: ‘Ritual influences the beliefs of his participants, and precisely for this reason it is also a prime target for political manipulation’ (Kyriakidis 2007c: 301).

In Italian archaeology, there has been little attention for theoretical matters, and pre- and protohistoric cult activities have consequently not received much consideration. Until recently, a generally accepted view has consistently opposed the ‘primitive rituals’ of the prehistoric periods to the well-structured religion ‘imported’ from the Aegean (Blake 2005). Studies, research and discoveries of the last 20 years have changed this and allow us to reconstruct the essentially indigenous evolution of this peculiar sphere of pre- and protohistoric Italian communities, without ignoring the essential question of an enduring dialectic between the different parts of the Mediterranean (see, e.g., Bettelli 1997; 2002: 146–64).

New types of enquiry explored in the last decade include a modern critical evaluation of ancient findings, often superficially classified in the sphere of ritual activities (Bianchin Citton and Malnati 2001). In the field of late protohistory more specifically, they are the analysis of mythology as the main type of ‘historical’ speculation in Archaic society (Carandini 2002) and the iconological and/or structural analysis of decorated bronze objects (Pacciarelli 2002; Zaghetto 2002; Cupitò 2003).

It is my intention in this chapter to scrutinise key aspects of cult activities in protohistoric central and northern Italy. I will do so by building on earlier work of my own (Guidi 1989–90; 1991–92; 1998; 2004; 2006; 2007–2008; 2009; 2010) and by others (Bergonzi 1989–90; Whitehouse 1992; 1995; Peroni 1996; Maggi 1996; Cocchi Genick 1996, 1999; Pacciarelli 1997; Domanico 2002; Rizzetto 2004; Bernabò Brea and Cremaschi 2009). Particular attention is given to the so-called Brandöpferplatzen, which are a type of large votive pyres well known north and south of the Alps, as these have been well studied in northeast Italy in recent years (Culti Alpi 1999; Niederwanger and Tecchiati 2000; Di Pillo and Tecchiati 2002; Zemmer-Planck 2002).

I have tried to distinguish the main characteristics of cult activities during four succeeding phases of development:

- Early Bronze Age (2300/2200–1700 BC);

- Middle Bronze Age (1700–1350/1300 BC);

- Late Bronze Age (1350/1300–950 BC), which is usually divided into the Recent Bronze Age (1350/1300–1250/1200 BC) and the Final Bronze Age (1250/1200–950 BC);

- Early Iron Age: this period begins around 950 BC and ends by 730/720 BC in Tyrrhenian central Italy, in the early sixth century BC in the Sabine region of central Italy, in the course of the sixth century BC in Adriatic central and northern Italy, and by the end of the sixth century in the Raetic area (roughly corresponding with Trentino-Alto Adige and surrounding mountainous districts).

As in other European countries, the new dendrochronological ‘revolution’ has had an impact on the absolute chronology in Italy as well (Pacciarelli 2000). I use the ‘high’ chronology, even if it is still not accepted by all (Bartoloni and Delpino 2005).

The Early Bronze Age: A Period of Transition

Only a few of the hundreds of Val Camonica rock carvings are dated to the beginning of the Early Bronze Age. In one of them (Cemmo 6), 34 anthropomorphic figures in parallel rows are depicted, hand in hand; one has a fringed short skirt and a sort of sun-crown, a motif deriving from the sun disks often depicted on Copper Age rock carvings (Casini et al. 1995). Another tradition that goes back to the Neolithic are votive offerings around thermal springs, presumably because of their therapeutic virtues. The most famous instance of the latter is the 8 m deep pit with wooden walls of Panighina di Bertinoro in Romagna. It was dug on the shores of a little stream, and many vases dated between the end of Neolithic and the beginning of Early Bronze Age were deposited, if not thrown, into it, along with ochre and/or various types of seeds (mostly nuts and cereals) and portions of sheep and cows (Morico 1997). Another site of this type is the Lago delle Colonnelle, a sulphurous spring near Tivoli (Rome), around which numerous sherds of Early to Late Bronze Age date were found (Mari and Sperandio 2006).

Many caves were used for burial, as in the Copper Age, but various types of votive offerings have been encountered in some of them, usually those with a water stream (Tomba dei Polacchi, near Bergamo), a natural airhole (Grotta dello Sventatoio, Sant’Angelo Romano, Latium) or a deep sinkhole (Pozzi della Pian, Umbria). These practices were subject to impressive growth in the Middle Bronze Age.

Alongside examples of dripping, i.e. vases collecting water from a stalagmite, or crevices in which vases were thrown, we have cases of vases deposited in holes. In the Grotta Sant’Angelo (Abruzzo), for instance, there is a pit (40×30 cm in diameter) surrounded by 12 smaller holes (15×20 cm) filled with carbonised wheat, suggesting a propitiatory rite. An impressive case is also the Grotta del Colle (Rapino, Abruzzo), where ritual depositions began in the Copper Age and continued until the Roman period (D’Ercole 1997b; D’Ercole et al. 1997).

A totally new ritual practice is the votive deposition of bronzes in hoards. This has been recorded at Cazzago Brabbia in the north, where four bronze necklaces were deposited in the water, and in Latium at Grotta Morritana, where six bronze axes and a vase have been found in rock gorges on the slopes of a mountain.

The Middle Bronze Age: Caves, Water Depositions and a New Cult Site

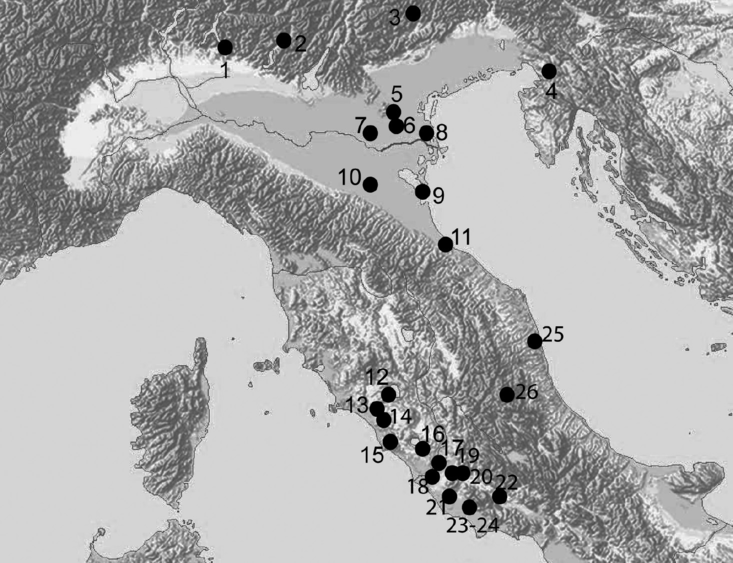

The ritual landscape of the Middle Bronze Age is unquestionably dominated by caves, especially in central Italy. The variability of the ways in which caves were used that have yielded burials or ritual evidence has led scholars to pursue two lines of explanation (Figure 37.1).

Figure 37.1. Distribution of Early Bronze Age and Middle Bronze Age sites mentioned in the text: 1. Cazzago Brabbia; 2. Imegna, Tomba dei Polacchi; 3. Valcamonica; 4. River Sile; 5. Noceto; 6. Casinalbo; 7. Redù; 8. Panighina di Bertinoro; 9. Cetona; 10. Titignano, Pozzi della Piana; 11. Ischia di Castro, Grotta Misa; 12. S. Angelo Romano, Grotta dello Sventatoio; 13. Lago delle Colonnelle; 14. Rocca Canterano, Grotta Morritana; 15. Cassino-L’Eremita; 16. Civitella del Tronto, Grotta di Sant’Angelo; 17. Rapino, Grotta del Colle (base map courtesy of the Ancient World Mapping Center).

Some have focused on a religious characterisation of cave occupation (Cocchi Genick 1996; 1999; 2002: 117–55; Grifoni Cremonesi 1996), while other scholars, including myself, prefer to distinguish between caves primarily destined for burial and those used as real ‘cult places’. A factual distinction may indeed be made, as the first type of cave is usually not as deep and smaller than the second one, which tends to be deeper and meandering, often crossed by watercourses (Bernabei and Grifoni Cremonesi 1995–96). In the second type of cave, the original entrance also tends to have been preserved, while burial caves are more often than not obstructed by stone collapses.

A common feature of many burial caves is an area set aside from the burials for offerings, usually pottery vessels. An exception is the complex of Monte Cetona in Tuscany, where various caves were used for ‘secondary’ depositions, some reserved above all to men, some to women and some to elite members.

The types of offerings deposited in caves derive from agriculture and animal husbandry and include both sheep/goat and cattle bones and carbonised cereal and legume seeds. In some caves, the seeds have been found in ritual hearths. The most famous case is Grotta Misa in Etruria, where at least four different sectors of wheat, flour, millet and broad bean carbonised seeds could easily be recognised in a circular hearth. In one case (Grotta dello Sventatoio, Monte S. Angelo, Latium), fragments of a sort of cake have been found that was made from a mixture of cereals, milk, honey and oil (Costantini and Costantini Biasini 2007: 790). In the same cave, three fragments of burnt infant skulls have also been found (Cocchi Genick 2002: 149).

As the few climate studies of the Bronze Age demonstrate clearly that the first half of the second millennium BC was a phase of considerable aridity (Angle 1996; Cerreti 2003: 11–12), this might explain the propitiatory agricultural rituals performed in the caves.

Another class of finds related to cult activities are weapons such as swords, spearheads and axes that were deposited in rivers and lakes or in the mountains. Sometimes they were left on the shores, but they were also deposited in the middle of rivers, as is demonstrated, for instance, by the hundreds of Middle and Late Bronze Age bronze weapons found by dredging in the River Sile, near Treviso). This practice is particularly well attested in north Italy and matches a tradition in central Europe.

Bianchin Citton and Malnati (2001) have proposed that in some cases, the composition of these finds can reveal the selective collection of objects originally associated in hoards (e.g. weapons found together with sickles). An alternative interpretation is that these depositions represent a kind of ‘reparation’ towards the deities of the elite who offered the weapons in public ceremonies to ‘normalise’ and readjust increased social inequality (Dal Ri and Tecchiati 2002). A comparable ritual has been attested in Cassino (southern Latium), where vases were deposited under an isolated peak called L’Eremita.

There are also many cases of domestic cults, as small vases and clay miniature models of carts, animals or (rarely) human figures are found in the terramare settlements. The two decorated gold disks from the terramare of Redù and Casinalbo seem comparable with the disk mounted on the well-known Trundholm cart model and must thus be linked to some form of ritual activity (Bettelli 1997).

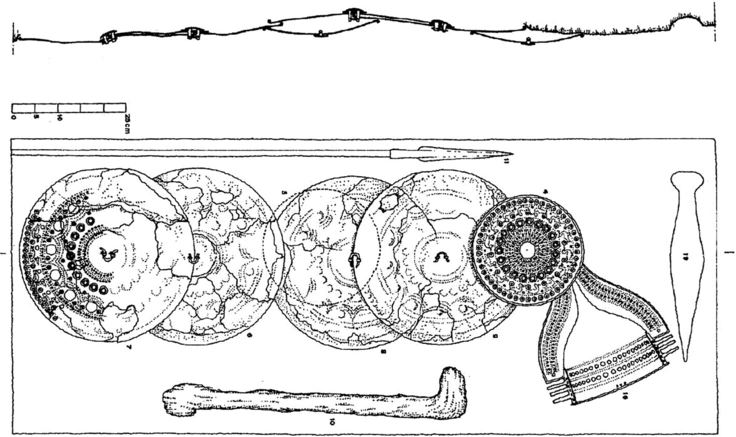

A recent remarkable discovery sheds new light on the religious beliefs of the terramare inhabitants, as a huge wooden basin was found just outside the Noceto terramare (Figure 37.2). It measures 11×6 m and is 3.50 m deep, and was originally filled with water (Bernabò Brea and Cremaschi 2009). More than 150 whole and fragmented vases were found on the bottom, together with miniature vases, figurines, cart models and many wooden objects. Most remarkable are the remains of at least four ploughs, deposited approximately at the four corners of the basin (Figure 37.3). The structure had not been built as a cult place but had first been used as a water tank, perhaps by a local elite member to protect against emergencies such as famine or bad harvests. It is perhaps no coincidence therefore that many of the objects subsequently deposited were associated with agriculture.

Figure 37.2. The Noceto wooden basin (photo Mauro Cremaschi).

Figure 37.3. One of the ploughs found inside the Noceto wooden basin (photo Mauro Cremaschi).

In general terms, the cult activities of the Early and Middle Bronze Age seem to recall the ‘pre-religious phase’ of Lévy-Bruhl, as the archaeological record has produced much evidence of rituals but none of a belief in superhuman beings.

The Late Bronze Age: Open-Air Cult Places

The almost complete disappearance of ritual activities in caves, which became absolute in the Final Bronze Age, is the most important characteristic of this period, in which chiefdom-like societies became widespread across the Italian peninsula. In some cases, social inequality became particularly marked, and overall the settlement pattern became noticeably more hierarchical with fewer but larger settlements, which would result in the first cities of the early Iron Age. Some examples of caves that continue to be used in this period (Figure 37.4) include:

- The already-mentioned Tomba dei Polacchi near Bergamo, where pottery has been found in hearths, as well as ash lenses and little holes filled with ochre and a bronze razor incised with a double axe (Poggiani Keller 2001; 2002).

- The Grotta delle Mosche (Fliegenhöhle) near S. Canziano in the Triestine Karst, which is a 50 m deep cave with votive offerings with strong male associations (1500 burnt, fragmented and twisted fragments of swords, helmets, spearheads, pins, including the oldest iron objects found in Italy; Bergonzi 1989–90; Gustin 2007).

- The Antro della Noce in the Monte Cetona caves complex, which has yielded three swords of Recent Bronze Age date, embedded in a small crevice.

- Two caves in the Gola del Sentino (Marche). One is the Grotta del Mezzogiorno, where a hearth with little holes filled with burnt seeds of wheat or broad bean was interpreted as a propitiatory rite for the sowing season. The other one is the Grotta del Prete, where two complete Late Bronze Age vases were found deposited in a Palaeolithic occupation level (Lucentini 1997).

- Grotta del Colle, which has yielded some sherds of the Recent Bronze Age (D’Ercole et al. 1997).

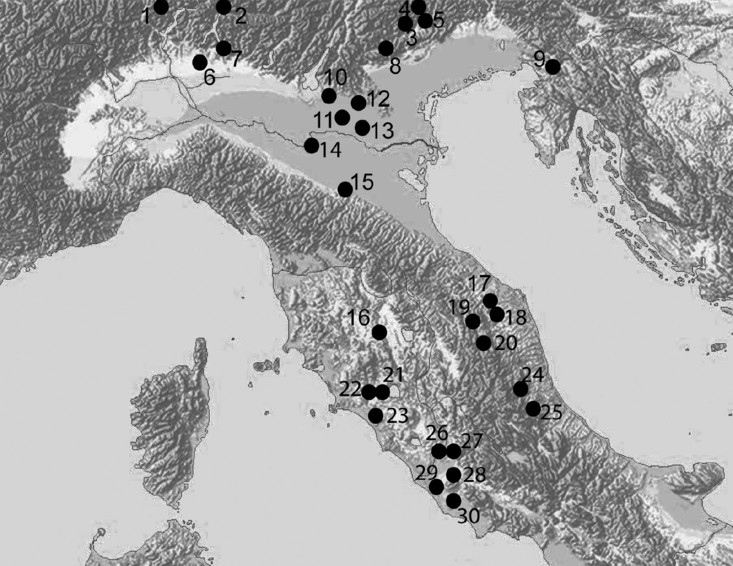

Figure 37.4. Distribution of Late Bronze Age sites mentioned in the text: 1. Formazza; 2. Passo dello Spluga; 3. San Maurizio Bagni di Zolfo; 4. Seeberg; 5. Mittelstillersee; 6. Malpensa; 7. Imegna, Tomba dei Polacchi; 8. Pergine Valsugana; 9. S. Canziano, Grotta delle Mosche; 10. Custoza; 11. Nogara, Pila del Brancon; 12. Desmontà; 13. Corte Lazise; 14. S. Rosa di Poviglio; 15. Borgo Panigale; 16. Cetona, Antro della Noce; 17. Monte Croce Guardia; 18. Gole del Sentino; 19. Gualdo Tadino; 20. Monte Primo; 21. Lago di Mezzano; 22. Sorgenti della Nova; 23. Banditella; 24. Rapino, Grotta Del Colle; 25. Risorgiva di Stiffe; 26. Roma; 27. Lago delle Colonnelle; 28. Pratica di Mare (Lavinium); 29. Nemi; 30. Campoverde, Laghetto del Monsignore (base map courtesy of the Ancient World Mapping Center).

The Late Bronze Age is characterised by a widespread appearance of cremation burials. The new ritual, which basically involves the destruction of the body, has a logical counterpart in the belief in some sort of survival of the deceased. An increased orientation towards the skies might well be related too. Another evident manifestation of this ideology is the miniaturisation of objects such as pottery, furniture, huts and bronze weapons, which is a particular feature of Final Bronze Age burials in the central Tyrrhenian area. As ‘chtonic’ or underground rituals were abandoned, open-air cult activities became the norm around this time. More or less in line with a recent classification proposed by Rizzetto (2004), four main types of cults may be distinguished:

Figure 37.5. Final Bronze Age shin guards from the Desmontà graveyard (from Salzani 1993).

Votive Offerings in Water Courses, Lakes and Springs

This is the most widespread type of ritual activity attested in the archaeological record of the Late Bronze Age, involving above all weapons such as swords, daggers, spearheads and axes (Bernabei and Grifoni Cremonesi 1995–96). A small number of knives and pins could be the remains of graves, while some other bronze objects such as sickles, especially when associated with weapons, could be the dispersed remains of hoards. Of an unmistakably ritual nature are remarkable finds such as swords firmly embedded in river bottoms, including 6.50 m deep in one case, in lake basins such as Mezzano in Etruria (Figure 37.6), and the 3000 bronze rings found near a sulphurous spring at San Maurizio Bagni di Zolfo, near Bozen (Bolzano).

Figure 37.6. Final Bronze Age swords ritually deposited in the Mezzano lake (Valentano, VT; from Baffetti et al. 1993).

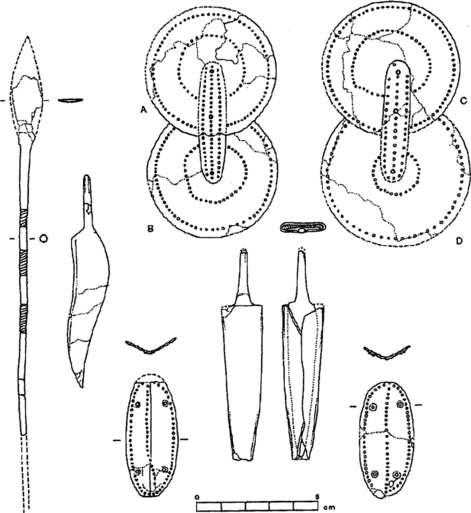

The ritual importance of water is also evident from the complex of walls and altars around the Mittelstillersee, a lake in the Renon area north of Bozen (Bolzano: D’Ercole 1997a; Bettelli 1997; Di Pillo and Tecchiati 2002; Domanico 2002). A significant find is the hoard from Pila del Brancon near Nogara (Verona), where a hoard of bent and broken metal objects was intentionally exposed to fire on the bank of a little stream. The hoard included swords, daggers, an axe, 51 spearheads and 73 bronze sheet fragments of protective gear such as cuirasses, helms and shin guards. This hoard has been interpreted as booty taken from defeated enemies that was dedicated to the gods (Rizzetto 2004). A similar explanation has been suggested for other European hoards of the same period (Randsborg 1995).

A peculiar type of evidence comes from two sites in the central Tyrrhenian area. One is the Banditella spring near Vulci, where an open-air cult site existed from at least the Recent Bronze Age. Bone items, glass beads and miniature vases were the first offerings of a large votive deposit that continued to be added to until well into the Archaic period (Figure 37.7). South of Rome, hundreds of miniature vases were deposited on the shores of the small lake del Monsignore near Satricum between the end of Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age.

Figure 37.7. Final Bronze Age and early Iron Age miniature vases found in the Banditella votive deposition near Vulci (Montalto di Castro, VT; from D’Ercole and Trucco 1995).

Because both Vulci and Satricum were to develop into proto-urban centres, the ritual sites demonstrate how these sites were already perceived as focal places of the settlement system.

Domestic Cults

In Emilia and in Etruria, miniature figurines have been reported from domestic contexts, as at the S. Rosa di Poviglio terramare, where 26 miniature horses were found (Bettelli 1997; Miari 2000). It is the extensively excavated Final Bronze Age settlement of Sorgenti della Nova, however, that has yielded the best evidence. At least two types of domestic cult have been attested:

- skull fragments intentionally turned upside down and deposited in a stone circle;

- hundreds of pig remains in an artificial cave of very young individuals, in many cases foetuses. A large number of pregnant sows and piglets had been slaughtered, which points to a ritual that Classical authors associated with the cult of Demeter (De Grossi Mazzorin and Minniti 2009: 44–45).

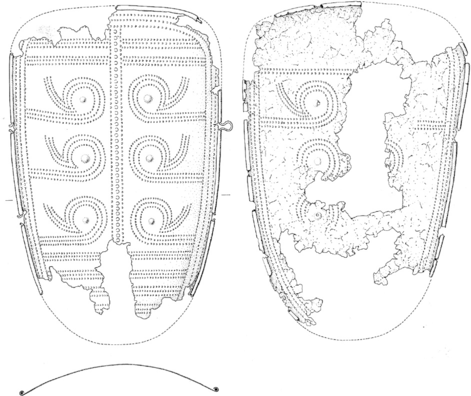

Further south in Latium, there are many archaeological finds that demonstrate a rapid development towards structured cult activities at the end of the Final Bronze Age. The most important one is surely the open-air cult site at Nemi, even if the prehistoric remains only consist of pottery and some wall fragments enclosed in a terrace of the later Diana sanctuary (Bruni 2009). Equally significant are the discoveries in Rome and surroundings at, for example, Pratica di Mare, ancient Lavinium, where male cremation burials with miniature weapons have been found (De Santis 2009; De Santis et al. 2010) (Figure 37.8). They include ritual double shields called ancilia that were later still used by the Roman priests of the Salii fraternity (Colonna 1991). These burials thus demonstrate how the end of the Bronze Age saw a small number of warriors combine the roles of military and religious chief among the communities of Latium.

Figure 37.8. Pratica di Mare, Final Bronze Age grave 21 with miniature double shields (from Colonna 1991).

A final point concerns divine images in the archaeological record of this period. There is undoubtedly an increase in anthropomorphic figurines in many settlements, and it has been argued that many pottery handles may be seen as a schematic representation of people (Damiani 2006; 2010). The most intriguing evidence is offered by statuettes in warrior cremation burials in Latium by the end of the Final Bronze Age and the beginning of the early Iron Age. While they may be seen as an image of the deceased (De Santis 2009), it has also been suggested that they could represent the Archaic goddess Ops Consiva (Torelli 1997).

Overall, the evidence for this period clearly indicates the emergence of true religious beliefs and deities perceived as superhuman beings, which required the intercession of a small group of ritual specialists in order to honour the gods and to seek contact with them. A further key feature of the period that continued to characterise the early Iron Age as well is the wide distribution of symbols associated with the sky (Fogelin 2007; Renfrew 2007).

The Early Iron Age: The Emergence of Civic Cults

The early Iron Age is characterised by the emergence of the first proto-urban centres, whose main characteristics are a radical change in size and a concomitant increase in functions fulfilled by these places (Guidi 2006; 2007–2008; 2010) (Figure 37.9).

Figure 37.9. Distribution of early Iron Age sites mentioned in the text: 1. Imegna, Toba dei Polacchi; 2. Breno; 3. Lagole di Cadore; 4. S. Canziano, Grotta delle Mosche; 5. Montegrotto Terme, S. Pietro Montagnon; 6. Este; 7. Lovara di Villabartolomea; 8. Adria; 9. Spina; 10. Bologna; 11. Verucchio; 12. Bisenzio; 13. Banditella; 14. Tarquinia; 15. Cerveteri; 16. Veii; 17. Roma; 18. Pratica di Mare (Lavinium); 19. Lanuvio (Lanuvium); 20. Velletri (Velitrae); 21. Ardea; 22. Caracupa; 23. Satricum; 24. Campoverde, Laghetto del Monsignore; 25. Cupramarittima; 26. Rapino, Grotta Del Colle (base map courtesy of the Ancient World Mapping Center).

This development took place first in Etruria at the turn of the millennium, which coincided with the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age. Latium, south of the Tiber, northeast Italy, and other regions such as Campania, Bologna and Verucchio soon followed suit, probably as outposts of the Etruscan centres. Other cities emerged in central and northern Italy between the eighth and sixth centuries BC. Radical change also occurred in the social structure that heralded what we can label the incipient early state.

A second step is the definitive transformation of these centres into true cities, which archaeological evidence situates in the second half of the eighth century in the central Tyrrhenian area, in the early seventh century BC in Emilia-Romagna and around the turn of the seventh to sixth century BC in the rest of northern Italy, which signals the emergence of a mature early state.

If signs of growing complexity of ritual activities can be detected in the ‘proto-urban’ stage, it is only during this phase that we can recognise organised religion with priests and civic cult sanctuaries (Renfrew 2007). Even in areas where cities never emerged, the evidence shows that cult sites were normally related to settlements. A widely accepted view is that protohistoric cult sites in Etruria and in Latium had been open-air sanctuaries before the monumental stone temples of the seventh century BC were first built. Many votive deposits in Latium, including Rome, are, however, associated with temples and contained early Iron Age items such as miniature vases, while in many cases such as Satricum, Lanuvium and Velitrae (Velletri), protohistoric huts have been brought to light (Guidi 1980; Ghini and Infarinato 2009: 313–15). An excellent example is found at Satricum, where the protohistoric hut was clearly centrally situated under the temple and hut-shaped clay temple models have been found. A similar situation has been brought to light at Ardea, while in Rome the first hut-shaped temple of Vesta has been reconstructed on the forum with a date in the second half of the eighth century BC (Carandini 2007) (Figure 37.10).

Figure 37.10. Reconstruction of the early Iron Age temple of Vesta, Rome (drawing Riccardo Merlo; from Carandini 2007).

In Etruria, a similar situation has been demonstrated in Tarquinia, where the following building sequence has been reconstructed (Bonghi Jovino 2007–2008):

At Cerveteri, recent fieldwork in a sacred area of the Archaic period has yielded several large huts that have been interpreted in ritual terms, while a large oval hut has been found under the Archaic sanctuary of Portonaccio in Veii (Ambrosini and Colonna 2010).

In short, the second half of the eighth century BC saw the emergence of the first ‘civic’ sanctuaries in many Etruscan and Latial proto-urban centres. At the same time, a careful examination of grave goods and the fragmented written evidence on Archaic Latin religion have identified interesting male and female burials that point to a progressive separation of leadership and ritual functions and the consequent emergence of specialised cult activities. Key find contexts include:

Figure 37.11. Early Iron Age grave of Veii, Casale del Fosso 1036, with normal size double shields (from Colonna 1991).

A first case in point is a remarkably grave of an 18-year-old woman in Ardea, which was found under the temple of Colle della Noce in association with protohistoric huts, perhaps hut-temples. A second one is an equally rich grave of a young woman in Caracupa, which was found under the polygonal walls of the hilltop settlement near an Archaic votive deposit. Several of the ceramic vessels from the latter have been decorated with schematic men and women. Taking into account the literary tradition that only Vestal virgins or priestesses of Vesta were entitled to burial within the pomerium or settlement areas of Rome and Alba, I propose that these burials are those of Vestal virgins and thus represent the transition to the urban phase and presumably the emergence of state religion.

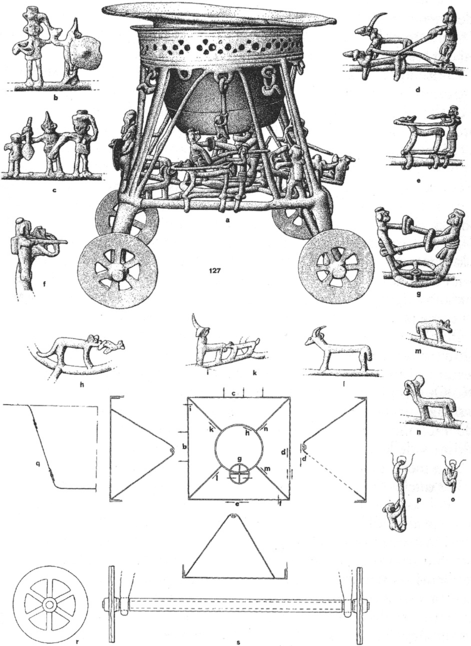

More important still is the opportunity to recognise both the survival of many Late Bronze Age symbols (Peroni 1994; 1996; Damiani 2006) and the presence of deities and mythological tales in pottery decoration and decorated bronze objects that are well known from Etruscan and Latin Archaic religion (Pacciarelli 2002; Delpino 2007; Brocato 2008). The famous cult wagon from a rich eighth-century female burial in Bisenzio shows, for instance, among its crowd of bronze figurines a divine couple who may perhaps be identified as Mars and Ops Consiva (Figure 37.12).

In central Adriatic Italy, the evidence for rituals in the early Iron Age is much poorer. In Abruzzi, Grotta del Colle saw votive offerings from the seventh century until the Roman period after an earlier period of abandonment. This cave and the first sanctuaries of the eighth century BC probably marked the boundaries between the different peoples known from ancient sources and epigraphic evidence (D’Ercole et al. 2003; D’Ercole and Martellone 2005).

In the Picene region of the modern Marche region, at least one votive deposition with hundreds of miniature vases is on record as dating to the end of the eighth century BC. It was located between the settlement and cemetery of Cupramarittima. These and other cemeteries of this period include pits with remains of sacrifices that offer other evidence of ritual activities. Another typical religious manifestation is the deposition of bronze statuettes that began in the early seventh century (Baldelli 1997; 1999; Naso 2000).

Apart from a 4 m deep pit that has yielded many beautiful bronzes of eighth-century date and later, and a ritual deposition of three shields from a central location in the Verucchio settlement (von Eles et al. 1997), the best evidence for a gradually increasing prominence of cult activities comes from northeastern Italy. It has been argued that a series of miniature vases and bronzes of early Iron Age date in this region testifies to a phase of cult activities preceding the first real votive depositions of San Pietro Montagnon, Este and Lagole (Capuis 2002). The presence of ‘civic’ sanctuaries situated around the largest settlements has now been demonstrated for Este between the end of the seventh and the beginning of the sixth century BC, which was also the final phase of urban evolution. These and other sanctuaries in the Veneto region are characterised by votive deposits of bronze figurines that represent warriors or deities (Pascucci 1992). It has been suggested that the Este sanctuaries and minor votive deposits of pottery and/or bronzes in Padova demarcate a border between the city and surrounding countryside (Gamba et al. 2008), while other sanctuaries, such as San Pietro Montagnon and Lagole, were strategically located in a ‘buffer’ zone on the borders of the Veneto territory (Capuis 2002).

Generally speaking, the early Iron Age in northern Italy saw continuity, even if on a smaller scale, of many Bronze Age ritual manifestations such as cave cults, with the votive offerings in the Grotta delle Mosche and the dripping in a vase at Tomba dei Polacchi, sun cults, Brandöpferplatzen and the votive offerings in water courses, basins and springs. Worth noting is the gradually stronger association between cult sites and settlements in the Raetic area (Poggiani Keller 2001; 2002; Gleirscher 2002; Niederwanger 2002).

Of the deities of this period, Reitia is well known from the Este Venetic inscriptions, and it has been suggested that she was already worshipped in this period (Gleirscher 2002). At Breno, in Val Camonica, a Roman sanctuary dedicated to Minerva has also yielded evidence of an Iron Age late sixth-century open-air cult place with an altar and burnt votive offerings. The bronzes include a small pendant representing a praying woman ‘emerging’ from a sun boat with bird-shaped tips, who presumably represents a local deity, possibly Reitia (Rossi 2010) (Figure 37.13).

Figure 37.13. Early Iron Age bronze pendant from Breno, Val Camonica (from Rossi 2010).

A final discovery worth mentioning is the swan egg found in the seventh-century cremation burial of a baby girl in Villabartolomea (Verona). Similar eggs have also been found in eighth-century burials in Bologna and Este. The swan is a powerful symbol as an aquatic bird that in ancient myths carried Apollo’s sun chariot, as well as being a symbol of rebirth, possibly in connection with Orphic rituals that were brought to northeastern Italy by Greek traders in the ports of Adria and Spina (Malnati and Salzani 2004).

Alongside the eventual emergence of structured religious activities, a collection of myths may be traced from this period, which underlines that most material and immaterial traits of Italian Archaic societies have deep roots in the early Iron Age. It is therefore no coincidence that the best evidence of religious activity may be found in elite burials, where rich grave goods include decorated objects such as the splendid bronze buckets of the northeastern Situlenkunst and abundant evidence of ceremonial drinking that attests to a lifestyle in which feasting played a crucial role (Renfrew 2007).

Concluding Remarks

In the evolution of cult activities in protohistoric central and northern Italy, three successive phases may be distinguished. This first is dominated by the ritual use of caves, which goes back to the Early and the Middle Bronze Age; it was characterised by a kind of ‘chtonic’ religion with an emphasis on propitiatory rites. The second is defined by widespread votive offerings in water courses, lakes and springs, as well as dedications on mountains and to the sun, with an evident interest in the skies; there is correlation between incineration and symbols such as the sun disk, sun chariot and anthropomorphic motifs between the Middle and the Late Bronze Age. The third is characterised by the emergence of the first proto-urban centres and ‘civic’ cults, i.e. a structured set of rituals with sanctuaries, deities and mythology that was managed and organised by full-time specialists between the end of the Bronze Age and the early Iron Age.

A further demonstration of the existence of real ‘sacred’ places are the caves and the Brandöpferplatzen that were reused in the Archaic and Roman periods, in some cases such as Grotta del Colle even until recent years. In conclusion, the evidence presented in this chapter demonstrates how, in each phase, rituals were not so much a pale reflection of socio-economic structure but, on the contrary, one of the driving forces of Italian protohistoric social evolution.