6 Late Bronze Age Sardinia: Acephalous Cohesion

Abstract

The late second millennium BC on Sardinia is among the most dynamic and vital periods in the island’s history, when Nuragic society undergoes massive changes. Proto-urban centers surrounding veritable fortresses, vast regional cult spaces, sophisticated metallurgy, and a complex circulation of Cypriot and Aegean goods and technologies attest to expanded political groupings and economic intensification. This period marks the apex of Nuragic society, and at the same time foreshadows this culture’s fragmentation in the subsequent centuries. These precocious transformations, virtually unparalleled elsewhere in the central and western Mediterranean in this period, have typically been explained by either external pressures or internal ones: the former theories focus on the foreign demand for metals and influx of new goods, while the latter emphasize demographic growth or a shift in the Sardinian mindset from introversion to extroversion. Yet the picture that emerges from the material record is one that the standard internal/external binary applied to islands does little to explain: a bewildering blend of connectivity and isolation, cultural conservatism and social change, and the appropriation of new and recycled material forms. This chapter reexamines this perplexing period, drawing on the evidence of imports and the built environment to construct a picture of a still inward-turning society whose emergent elites were unsuccessful at overcoming a tradition of acephalous cohesion.

Introduction

Probably more than any other region in Italy, studies of Sardinia in the late second millennium BC emphasize overseas contacts, from finds of Baltic amber, metal objects of possible Cypriot and Iberian origin, and Mycenaean ceramics on the island (e.g., Lo Schiavo et al. 1985; Balmuth 1987; Tykot and Andrews 1992; Ridgway 2006). The picture of Sardinia in the Late and Final Bronze Ages as a cosmopolitan hub for visitors traveling east and west is in notable contrast to the preceding Early and Middle Bronze Ages on the island, when the virtual absence of imports and peculiar localized megalithism speak to an isolated and introspective culture. Through most of the second millennium BC, Sardinia was inhabited by an egalitarian society of farmer-pastoralists whose most remarkable gesture was to build for their dwellings massive conical dry-stone towers, the nuraghi (Figure 6.1). These constructions are generally understood to be the outcome of social competition in a closed insular environment, an ‘Easter Island’–type adaptive behavior (Patton 1996: 185).

Figure 6.1. Nuraghe Ruju (Filigosa; photograph by Peter van Dommelen).

By the Late Bronze Age (LBA, 1350–1100 BC: Lo Schiavo 2001: 131–33), not only does Sardinia seem involved in the pan-Mediterranean circulation of goods and peoples, but its population becomes increasingly stratified, and the stone towers, no longer simple farmsteads, are expanded in some cases to serve much larger communities, presumably under the direction of emerging elites. Webster (1996: 111–25) proposed a three-tiered settlement hierarchy, with estimates of 5000 or so single tower nuraghi, another 2000 or so multi-towered structures (labeled Class II nuraghi), and just 14 known Class III settlements, vast complexes with many connected towers and an additional circuit of fortification walls (Figure 6.2). While the distinctions in wealth suggested by the Class II settlements are in keeping with those observed in other areas of the central and western Mediterranean in the same period, the Class III settlements point to a level of social and political complexity with few parallels in the central and western Mediterranean. These two material phenomena, the emergence of a settlement hierarchy and the presence of imported objects, have drawn the attention of scholars studying the period (see most recently Russell 2010). What has proven difficult, however, is to connect the two phenomena (or rather two categories of phenomena) ‘on the ground,’ as the two are largely spatially distinct. The monumental Class III nuraghi are no more likely than other Nuragic settlements to yield finds of foreign objects, and the distributions of exotica do not cluster in the region where most Class III nuraghi are found (see Russell 2010: fig. 6.2). This article reexamines this perplexing period, using the evidence of several categories of imports to suggest first that the notion of an outward-looking island in the LBA has been overstated, and second that the emergent elites were unable to harness the new economic opportunities presented by foreign contacts.

Figure 6.2. Nuraghe Seruci (Gonnesa), a Class III nuraghe (photograph by Peter van Dommelen).

Nuragic Settlement and Society

The nuraghi, usually conical in form and several stories high when intact, are unevenly strewn around the island, with densities greatest in the hilly regions of the north-central zone. There are an estimated 7000 of them known. The earliest such towers emerge around 1800 BC, with construction peaking in the Middle Bronze Age, around 1500–1350 BC. The simple single tower nuraghi were residences, and their dispersed arrangement and loosely equivalent dimensions suggest an egalitarian society. The structures are varied enough in construction details that they seem to have been locally planned and built, probably involving the aid of neighbors (Trump 1991; cf. Lilliu 1988 and Webster 1996 for good overviews; and Usai 1995 for other possible explanations of the towers’ function).

The multi-towered complexes emerge in the LBA, beginning around 1350 BC: of the estimated 7000 nuraghi, 2000 are complex. One or more towers were added to the original tower, with walls linking the towers together to form one large structure (Webster 1996: 112). A very small subset of these complex nuraghi have a further surrounding wall with additional towers enveloping the central structures: these are the Class III nuraghi (Webster 1996: 117). At least a few of the complex nuraghi, such as Nuraghe Arrubiu, were built from scratch, but most seem to have been expanded from single tower nuraghi over one or more phases of construction (Lo Schiavo and Sanges 1994: 69) (Figure 6.3). Nuraghe Su Nuraxi of Barumini, as interpreted by Lilliu (1955), constitutes the model of this multiphase construction process, against which the chronologies of other nuraghi are compared. Many nuraghi of all types had surrounding villages of huts by the LBA. Both the Class II and Class III nuraghi contribute to the picture of an increasingly complex society in a period of demographic growth. These changes in settlement are accompanied by an influx of new pottery and metal objects, and the appearance of regional-scale cult sites. Lo Schiavo (2001: 134) has labeled the agglomerations of nuraghi, ‘nuraghe-less villages,’ and other monuments as ‘nuclei,’ the members of which communally controlled the natural resources of the surrounding territory. These arrangements speak to a tribal society and a decentralized territorial system. However, in the southern portion of the island, the settlement pattern is different. With only one exception, the Class III settlements are located there, on lands with the agricultural potential to support larger populations than the uplands of the central and northern zones (Webster 1996: 131). The Class III settlements, by their size and given the labor entailed in their construction, suggest some sort of regional authority. Webster (1996: 131–32; fig. 52) has constructed Thiessen polygons for each of the Class III settlements and shown that they are at least 10 km apart, with hypothetical territories of 200 km or more, containing hundreds of smaller settlements and ritual sites. Webster (1996: 131) estimates the population of each of these polities to have been in the tens of thousands.

Figure 6.3. Nuraghe Arrubiu (Orroli; photograph by Peter van Dommelen).

That much is broadly accepted. Less understood are the sources of the wealth and social power evident in the Class III settlements. Giardino (1995) sees the concentration of these large settlements near the Iglesiente mining region in the southwest as purposeful, but the extensive traces of metalworking and finds of local copper bun ingots at Nuragic settlements of all sizes, not just at the Class III sites, make the claim that these Class III occupants controlled the metal industry hard to support. Rather, the LBA metalworking industry on the island was apparently decentralized, with myriad local production sites at various nuraghi and sanctuaries. Further support for the theory of an acephalous industry comes from the extreme variability in the elemental composition of the locally produced plano-convex ingots. This variability suggests a nonstandardized smelting process, with each site making its own decisions (Stech 1989: 41). Thus, even in this period when social stratification is evident, the residents of individual nuraghi seem to have maintained considerable autonomy in metallurgical production.

If the industry itself was not controlled by regional authorities, one might reasonably expect the control of imported raw materials to be a source of power. Local copper and lead were abundant, but copper may nevertheless have been imported, in the form of oxhide ingots discussed in the section Copper Oxhide Ingots below, and as yet there is no evidence that the few local cassiterite tin sources were exploited. Instead, it appears that tin was imported to the island and added to the local copper (Valera and Valera 2003). As for the possibility that copper was imported, none of the Class III settlements has yielded oxhide ingots or tin, although there are 32 known find spots on the island; it should be noted that only a few sites have yielded tin anyway (see Lo Schiavo 2003a). Nor can other imports have been the basis for the power of these settlements: Aegean sherds have been discovered at just 3 of the 14 Class III nuraghi. Put another way, the Class III nuraghi amount to 18% of the 16 find spots of Aegean sherds on the island (Russell 2010: 110; and see Vianello 2005 for a complete gazetteer of find spots of Aegean materials). While this percentage is far higher than the ratio of Class III nuraghi to nuraghi overall, when we consider the Class III towers as a portion of the couple hundred excavated nuraghi, the 18% becomes less remarkable. Likewise, amber is found at some Class III settlements but turns up in many other sites as well (Negroni Catacchio et al. 2006). To conclude, while it is in the Class III nuraghi that one would expect to find the highest numbers of the presumably valuable commodities of the day – imports and metals, this is not the case. As Webster (1996: 142) noted, it is not yet possible on present evidence to demonstrate any close relationship between settlement size, proximity to native ore sources, metallurgical production, and trade activity. Some coastal sites have rich ceramic imports and little metal (Antigori, Sa Domu ‘e S’Orku), while other sites have rich metallurgical output and few if any ceramic imports (Funtana), irrespective of size.

Webster proposed that the basis of wealth and power in Nuragic Sardinia cannot have been control of metals or exotica. Instead, he saw wealth derived from labor and livestock, drawing on the similarities in the layout of complex nuraghi to the southern African kraals and associated settlements with livestock-based economies (Webster 1996: 125–28). This theory has implications for more than just the Class III settlements: I would posit that some combination of farming and stock-raising constituted the basis of the Nuragic economy everywhere, and that the island was no more ‘extroverted’ in the LBA than it had ever been. When we look more closely at the distributions of the imports, this theory finds further support.

Late Bronze Age Imports to Sardinia

On Sardinia in the LBA and Final Bronze Age (FBA, 1100–900 BC), foreign goods arriving on the coast penetrated far into the interior. Indeed, many of the imports, including the oldest known Mycenaean import to the island, an alabastron from Nuraghe Arrubiu (Orroli), are from inland sites, not coastal ones. A glance at the map demonstrates that the imports, far from accumulating at the coast and trickling in progressively thinner streams toward the interior, show no preference for coastal sites. The only exception to this is Nuraghe Antigori (Sarroch) in the south (Ferrarese Ceruti 1986). It is located on a hill overlooking a good natural harbor. As the structure is partly built into the hilltop and poorly preserved at the top, its original form is difficult to make out, but with five intact towers and other ancillary structures surrounded by stretches of wall, its categorization as a Class III settlement seems warranted (Lilliu 1988: 399–401). It has yielded the largest assemblage of Aegean-type pottery on the island, dating to LH IIIB and LH IIIC, with pieces provenanced to Crete, the northeast Peloponnese, and of local production (Jones and Day 1987). The island’s first piece of iron was found at Antigori, as well as the only Cypriot pottery there. Among all the sites on Sardinia, it thus comes closest to the picture of a node in the intensive maritime trading network of the end of the second millennium BC in the Mediterranean. For mainland Italy, Vagnetti has drawn a triple distinction between the internationally oriented coastal trading centers where Cypriot pottery is found, the inland settlements where it is not, and those that have yielded only isolated examples of Aegean-type sherds, more often than not locally made imitations (Vagnetti 2001: 88). In southern Italy, the coastal centers were at the top of the settlement hierarchy in terms of size, monumentality, and quantities of foreign and other luxury objects (Affuso and Lorusso 2006). How does this compare with Sardinia? This penetration of Sardinia’s interior could be read as evidence of the rootedness of the foreign imports. However, given the absence of powerful coastal settlements, it may mean quite the opposite: the goods moved to the interior precisely because the economy was not structured around them. The agricultural interior was the source of wealth. Regardless of the mechanisms of trade on LBA Sardinia, that is, whether the foreign traders moved the goods inland themselves, or there were middlemen, or locals responsible for the overland transport, goods must have moved toward demand. So the conclusion we must draw is that unlike southern Italy, wealth was not concentrated along the coast. This can only mean that foreign exchanges were of minor importance to the Sardinian economy.

Further, there is little overlap in the distributions of imports. Lo Schiavo attributes the distinct distributions of Mycenaean pottery and Cypriot metals – the former primarily in the south and the latter spread all over the island – to the actions of the foreign visitors: she suggests that the Cypriots became more integrated into Nuragic society, whereas the Mycenaeans merely used Sardinia as a stopping-off point, perhaps on the way to Iberia (Lo Schiavo 2004: 379). But from what we know of Bronze Age trade in the Mediterranean, which seems to have been primarily maritime with goods exchanged at coastal sites, it seems far more likely that the differing distributions inland are a function of local relations and local economies (see Manning and Hulin 2005: 280–82). Therefore, the disparities in distribution suggest, much like the disparities in metallurgical production, that the circulation of foreign goods proceeded in a localized and nonstandardized manner.

How are clusters of interactions visible from the archaeological record? It is generally very difficult to calculate the flows of local interactions in prehistory. We are largely restricted to exchanges of objects rather than of peoples or ideas, and exchanges over short distances are even harder to detect. Among the kinds of goods that would circulate locally, perishables such as foodstuffs are rarely retrieved archaeologically, and in the case of pottery, microregional differences in clay sources are unknown in most areas. Here is where the imports come in handy: they can be treated as evidence of localized interactions when they turn up at inland sites, not just as indices of foreign contacts.

In the LBA and FBA, imports reaching Sardinia may be grouped into several major categories: Aegean imports and imitations, Cypriot-style goods (both ceramics and metals), amber, and Iberian imports. For the purposes of this chapter, I will focus on the best provenanced and best dated of these materials, the Aegean-style pots, the copper oxhide ingots, and two amber bead types – the Tiryns and Allumiere beads. Linking the various categories of materials is a challenge. The bulk of the Aegean pots date to the thirteenth and early twelfth centuries BC, which is contemporary with the few Cypriot ceramics on the island, and both are concentrated in the south (Vagnetti 2001: 78–80; Jones et al. 2005: 541). The Cypriot-style metals, for which it is virtually impossible to confirm if they are imported or locally made, belong to the twelfth and eleventh centuries BC, with some objects dating to the tenth century BC (Lo Schiavo et al. 1985: 63). While some Cypriot-style oxhide ingots have been found in the south, they cluster more in the central zone. The Tiryns and Allumiere beads date to the twelfth century BC but do not overlap spatially with the other imports (Cultraro 2006: 1543–44). The Iberian metals belong to the eleventh and tenth centuries BC (Lo Schiavo 1999: 506; 2003b: 159). It seems that we have the remnants of at least four distinct sets of interactions, preventing any easy generalizations about the nature of extra-insular contacts. Instead, we can use the distributions of these different groups of goods to highlight local social interactions on Sardinia (Lo Schiavo 1999; 2003a and 2003b; Lo Schiavo et al. 1985).

Aegean Objects

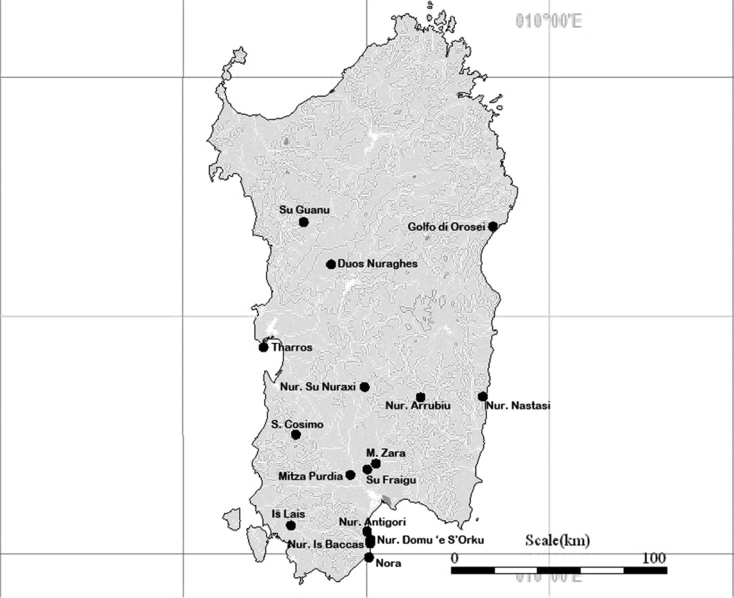

Aegean imports consist primarily of Mycenaean pottery. Mycenaean-style pots are known from 16 sites on the island (at last count, Lo Schiavo 2003b: fig. 2), totaling fewer than 100 sherds, both imported and locally produced (Figure 6.4). Of these, more than 50 sherds come from the site of Nuraghe Antigori alone. The above-mentioned alabastron that is the earliest imported Mycenaean vessel dates to the thirteenth century BC (LH IIIA2; Lo Schiavo and Sanges 1994: 68–70). The rest of the Aegean sherds date to LH IIIB and LH IIIC (Jones et al. 2005: 541). Open forms make up 61% of the finds, with bowls and cups prevailing (Vianello 2005: 45; table 8). Archaeometric analyses have determined that the Mycenaean wares on Sardinia are about evenly split between imports and local products (Jones et al. 2005: 540; see also Jones and Day 1987). Among the imports, just under two-thirds are from the Peloponnese, the rest from Crete (Jones et al. 2005: pl. CXXa). As for the local imitations, the quantities of sherds at Antigori make it likely that production took place there (Jones et al. 2005: pl. CXXIIb). In addition to the 16 find spots of pottery, at a site near Decimoputzu, an ivory figurine of a miniature warrior head with boar’s tusk helmet was almost certainly carved in the Aegean. The head, of hippopotamus tooth, dates to LH IIIA2–B, based on comparanda (Lo Schiavo 2003b: 157). The Mycenaean imports do not indicate what the Mycenaeans were after. Although the Mycenaean find spots on Sardinia cluster in the southern part of the island, their distribution does not seem linked to the copper sources in any obvious way (contra Ridgway 2006: 301–302; see also Russell 2010: fig. 6.2). Nor is there any overlap between sites showing evidence of extensive metalworking or with many metal finds, and ones with Aegean sherds (Webster 1996: 142).

Figure 6.4. Map of Sardinia showing find spots of Aegean pottery (prepared by Emma Blake).

As for their impact, the Mycenaean pots on Sardinia cannot be linked directly to the emergence of an elite on the island. First, the numbers are fairly low. Second, Mycenaean pots are found at nuraghi of all classes, not just the complex ones. The alabastron from Nuraghe Arrubiu was found just beneath the foundations of the nuraghe, presumably as part of a foundation offering. The nuraghe, covering 3000 sq m and with its five surrounding towers, is one of the biggest on the island (Lo Schiavo and Sanges 1994). Someone already had the means to build such a massive monument when the pot was deposited: the moment of construction and the placement of the pot is a culmination of a process of change, not the beginning, and the Mycenaean pot cannot be understood as a catalyst.

What the Aegean sherds’ distribution does suggest is a network of interactions linking a large swathe of the southern part of the island known as the Campidano Plain, including sites of all sizes, but not extending much beyond it. Presumably the pots arrived at Antigori or were made there, and then moved inland, but only so far. With a couple exceptions, the cutoff seems to be at the transition to the upland regions, suggesting not the boundaries of a polity but rather a regional grouping perhaps derived from similar economies and topography.

Copper Oxhide Ingots

The copper oxhide ingots undoubtedly constitute the most famous of the island’s imports, if that is indeed what they are. These objects have been found at 32 sites on Sardinia (Figure 6.5) (Jones 2007: 429). While oxhide ingots were made over several centuries in different places, the Sardinian examples, all very late in the production sequence (twelfth and eleventh centuries BC), have been posited by some scholars to be of Cypriot origin. The proposed ore sources for the ingots from 1250 BC on are the northwest foothills of the Troodos mountains, based on a lead isotope signature that is consistent with the copper deposits there (Gale and Stos-Gale 1999). While this provenance has found acceptance among a few scholars (e.g., Lo Schiavo 2006: 1321; and see Kassianidou 2001 for a nuanced evaluation of the evidence), many others are not convinced, given the widely recognized problems with lead isotope analysis for copper sourcing (e.g., Budd et al. 1995; Knapp 2000: 36–47). Among those who favor a Cypriot origin for the ingots, Lo Schiavo (2003b: 161) suggests that the oxhide ingots may have constituted ‘anchorage dues,’ as the Cypriots stopped off on their way to Iberia, although the absence of any confirmed contemporary Cypriot import in Iberia makes this explanation highly contentious. Perhaps the issue is not so significant after all: Gale and Stos-Gale (1987: 162) have calculated that the number of imported ingots to Sardinia may amount to no more than one shipload. This hardly constitutes an ongoing supply that warrants explaining. Even if they were not imported from Cyprus but were either made locally or imported from elsewhere, the form itself is evidence of Sardinia’s participation in the Mediterranean-wide metals trade, and so is a testament to foreign contacts.

Figure 6.5. Map of Sardinia showing find spots of copper oxhide ingots (prepared by Emma Blake).

At only two Sardinian sites have the ingots been found intact, and both were inland sites. Serra Ilixi (Nuragus), more than 40 km from the coast, yielded five intact oxhide ingots. Sant’Antioco di Bisarcio, 30 km from the coast, had two intact ones (Lo Schiavo 2006: 1329). More than 95 others, from the remaining 30 sites, were found in fragmentary form. For the most part, the ingot fragments turn up in hoards at nuraghi, villages, and cult sites, although in the case of the early discoveries, the term ‘hoard’ was applied very loosely indeed, so those contexts are questionable (Lo Schiavo 2003b: 158). Kassianidou (2001: 105) notes the ingots’ association with metallurgical tools at probable workshop contexts as proof of their practical use, but the lead isotopic signatures of the ingots are not consistent with those of any finished bronze artifacts on the island. Those bronze objects that have been analyzed have lead isotope signatures indicating that they were made of Sardinian copper (Gale and Stos Gale 1987: 154–55). This could mean that, on Sardinia, the oxhide ingots were not considered convertible material in a standardized form to be melted down to make other products (Muhly 1996). A more likely explanation is that local lead, added to the copper along with the tin in the alloying process, disguised the isotopic signature of the small original traces of lead in the ingots (Begemann et al. 2001: 74; Kassianidou 2001: 106–107). Even if some ingots were melted down and used though, there were clearly portions of many that remained out of circulation. This has led some scholars to suggest a symbolic or religious significance for them. Lo Schiavo (2003a: 121), for example, suggests that the Abini ‘hoard’ may in fact have been troves of votive offerings from a sanctuary that was overlooked in the looting entailed in its discovery. The Nuraghe Albucciu hoard, whose composition does not resemble either a trader’s hoard or a founder’s hoard, was also likely a votive hoard (Begemann et al. 2001: 62–65). Furthermore, the ingot fragments’ presence at sanctuaries and their preservation in later early Iron Age (EIA) contexts may indicate ritual significance. Perhaps the two functions were not mutually exclusive: there is some evidence that foundries were attached to sanctuaries, as the finds from the sanctuaries of S’Arcu ‘e is Forros (Villagrande Strisaili) and Sant’Anastasia (Sardara) suggest (Ugas and Usai 1987; Lo Schiavo 2003a: 124). From that perspective, perhaps the high numbers of oxhide ingot fragments on Sardinia are evidence not of relatively large quantities reaching the island, but rather of relatively large quantities that were not melted down. This added significance may explain the ingots’ surprising presence in later contexts. They were preserved in hoards and cult sites on the island for centuries after they were made and presumably reached there.

The other metals of Cypriot type on Sardinia also date to the twelfth and eleventh centuries BC. In the absence of any provenancing other than stylistic, that they are imports cannot be confirmed, so we can at best observe that the objects are Cypriot in style. Whether imported or locally made, their contemporaneity with the ingots suggests a period of intensified contacts with Cypriots in the twelfth and eleventh centuries BC (Lo Schiavo et al. 1985: 63). Unfortunately, the finished metals are mostly from unprovenanced contexts. These objects include weapons such as daggers, accessories and furnishings such as mirrors and stands, and, particularly intriguingly, the complete complement of smithing tools – hammers, tongs, and shovels (Lo Schiavo 2003b: 159). These tools, together with the Sardinian adoption of Cypriot metalworking techniques such as casting molds, suggest influences of a very different nature than the Mycenaean materials or earlier Cypriot pots bear witness to, and the differential distributions bear this out. Lo Schiavo (2001: 141) suggests that Cypriot metalworkers may have stayed on the island seasonally, leaving behind the products of their knowledge but no material traces of a permanent presence. Without supporting evidence, this theory is necessarily highly speculative. Whatever the nature of the Cypriot influence, the Sardinian smiths branched off on their own to produce a vibrant repertoire of objects (Lo Schiavo 2003b: 159). Matthäus (2001) argues that the Cypriot-style objects are indeed imports and that these continued to reach the island as late as the tenth and ninth centuries BC, although by then reduced to prestige goods rather than utilitarian tools, as EIA Cypriot pieces from the Sant’Anastasia well temple indicate (Ridgway 2006). Without further metal provenancing studies, the discussion remains conjectural, beyond observing that clearly Cyprus and Sardinia had contacts for a time, intensifying in the twelfth and eleventh centuries BC.

Lo Schiavo (1999: 508) finds the thorough distribution of the ingot fragments surprising, noting ‘The capillary nature of the penetration and diffusion of finds seems inconsistent with what we know about the structure of Nuragic society in the Final Bronze Age’ (my translation). Yet in light of the theory that wealth in Sardinia was derived from labor and livestock, not metals and trade, we would expect objects of value to penetrate the interior. The ingots are found in a wide zigzagging band from the northwest zone to the east central zone and the south (Figure 6.5), and their distribution, by whatever means, demonstrates the magnetism of interior sites. In their circulation, presumably some were melted down and others resignified as noncirculating inalienable objects. The ingots’ initial dispersal may have helped to reinforce regional networks across distances. Chapman’s (2000) study of the social significance of the dispersal of fragmented objects in the Neolithic and Copper Age Balkans resonates here. Chapman argued that this fragmentation was deliberate, and that it was part of a strategy of creating enchained social relationships between peoples in a collectively oriented society (see Braun and Plog 1982 and Talalay 1987 for earlier discussions). Drawing on Chapman’s model, if the ingots’ inalienability had to do with a perceived sacredness, it was one whose power was shared, not restricted, and may have served to promote connections between people. The ingots are also thought to have been sacred in Cyprus, but in a different way. There, the ingots came to be associated with the exclusive control of the metallurgical industry as practiced by the elites, embodied in the figurine of the so-called ‘Ingot God’ from Enkomi (Knapp 1986). In the Sardinian case, the ingots seem to have operated in quite the opposite manner, passing fluidly through nonelite hands.

Amber Imports

Amber beads are found in the hundreds at Nuragic sanctuaries and in tombs on Sardinia (Negroni Catacchio et al. 2006: fig. 6). While the material is indisputably imported, whether the beads arrived as finished products or were worked locally is a matter of debate. Lo Schiavo (2003b: 157) asserts that in some cases the beads were produced locally from imported amber, and in other cases the beads themselves were imported. Negroni Catacchio et al. (2006: 1461) see the distinction as chronological, suggesting that prior to the Iron Age, amber circulated as finished objects rather than as unworked material to be processed at many sites. The matter is not helped by the difficulties in dating most of the beads with any accuracy. Limiting the study to the Tiryns and Allumiere beads helps to focus the discussion, although the low numbers of these particular types underrepresent the actual quantities of amber on the island. The Tiryns beads are subcylindrical with a ridge around the central part. The Allumiere beads are cylindrical with grooves encircling them. Their shapes can range from squat to narrow (Negroni Catacchio et al. 2006: 1460). The lack of formal standardization suggests multiple production centers, but again it is unclear if any were in fact made on Sardinia. The two bead types are often found together (Negroni Catacchio et al. 2006: 1460). The contexts of the finds for the Tiryns and Allumiere beads in Greece strongly point to a date of LH IIIC, with the earliest examples dating to the early part of this period and the latest to Final LH IIIC, with their production and circulation ceasing in the sub-Mycenaean period (Cultraro 2006: 1543–44). In the west, Sardinia has among the highest concentrations of the Tiryns and Allumiere beads (Negroni Catacchio et al. 2006: 1460). It is still debated where the beads were produced. As no Tiryns and Allumiere beads are found near the Baltic, it seems unlikely that they were worked and distributed from there. With Greece at the center of the distribution map of these objects, it seems likely that they were made there and then fanned out to the west and east (Negroni Catacchio et al. 2006: 1461–63).

Regardless of their place of origin, what is of interest here is how they functioned on Sardinia. Nine of the 13 find spots on the island are in the interior (Figure 6.6). While this preference for the interior mirrors the distribution of the ingots, the mechanisms for the beads’ arrival on the island seem to have been quite different from those of the other imports discussed already. The beads show no preference for the south coast and were probably not reaching the island via Nuraghe Antigori. Nor do the find spots map easily onto those of the Cypriot-style ingots: although the beads cluster in the northwest and east central parts of the island along with the ingots, the two imports have only two shared find spots. The density of similar beads in west central and northern Italy suggests that the amber reached Sardinia from its Baltic source by way of the Tyrrhenian from the Italian peninsula, rather than directly from Greece or Cyprus (see Negroni Catacchio et al. 2006: fig. 8 for possible routes).

Figure 6.6. Map of Sardinia showing find spots of Tiryns and Allumiere amber beads (prepared by Emma Blake).

Discussion: External Contacts and Internal Cleavages

These imports thus demonstrate spatial and temporal clustering. Spatially, some of these clusters map understandably onto traversable lowlands such as the fertile Campidano Plain linking Cagliari and Oristano. Others, such as the cluster of ingots in the high altitude Gennargentu Mountains, can hardly be ascribed to ease of mobility (although see Riva 1997: 79 on the facility of interaction in mountainous regions). Reconstructing the mechanisms by which these goods reached Sardinia is a challenge. First, there were the Mycenaean imports to the south of the island, with the Cypriot pots likely arriving with those. Not only are the Cypriot pots found at Nuraghe Antigori, the site with the most Mycenaean material, but in at least one case, a Mycenaean import to the island has its closest parallel in Cyprus: a rhyton from Antigori, dating to LH IIIBI, has a twin from Enkomi (Lo Schiavo et al. 1985). The Sicilian site of Thapsos shows a similar combination of Cypriot and Aegean pottery from this period. Whether the traders who brought these goods were Mycenaeans or Cypriots remains open to debate. These visits must have been followed by a separate phase of Cypriot influence in the twelfth and eleventh centuries BC, the circumstances of which are less clear because of the problems of securely identifying the provenance of the objects in question. Roughly contemporary with this second wave of Cypriot influence, but apparently unrelated to it, amber imports were reaching the east coast of the island from the Italian mainland, as they may have done for centuries. Finally, Sardinia participated in multilateral interactions in the eleventh and tenth centuries BC with the Atlantic, mainland Europe, and the East, although the mechanisms for these remain unclear.

The sporadic influx of exotica must have been greeted with considerable enthusiasm by the Nuragic peoples, but only the Cypriot contacts of the twelfth and eleventh centuries BC can be said to have had a lasting impact – in this case on Sardinian metalworking technology. The Sardinians absorbed metallurgical methods and forms from the Cypriots in a process Lo Schiavo (2003b: 161) has called ‘cultural osmosis.’ But one piece of evidence suggests the Sardinians and Cypriots operated in distinct object worlds: the treatment of the oxhide ingots points to a radically different valorization of these goods, one that was due not to supply but to a cultural framework that granted certain objects an amuletic quality. Further evidence, though indirect, may come from the miniature pilgrim’s flasks: these seem to be local copies of Cypriot or North Syrian four-handled round or ovoid vessels dating to the twelfth to tenth centuries BC. No originals have turned up on the island, but the form is distinctive enough to make the identification plausible. The miniature bronze flasks have been found exclusively in Nuragic sanctuaries in FBA and EIA contexts and, interestingly, in EIA graves in Etruria (Lo Schiavo 2003b: 154–55). Lo Schiavo interprets the miniatures as evidence of the special reverence in which the full-size vessels were held, possibly due to their contents, now unknown. I would suggest further that these fetishized objects become uniquely Nuragic in their miniature forms. As I have argued elsewhere (Blake 1997), LBA and FBA Sardinia elites were not above manipulating symbols for their own ends, as in the case of the miniature multi-towered nuraghi. But the Cypriot elite’s interleaving of divinity and commodity, evident in their treatment of the oxhide ingots, is absent here. These distinct approaches to materiality may not have hindered interactions, but they must have mitigated their impact.

As for the Mycenaean materials, as we have seen, there is even less of a case to be made for influence. Webster argues for endogenous factors behind Sardinia’s social changes in the LBA: higher population densities led to increased social and economic insecurity, opening a space for some individuals to gain a foothold over the rest of the population. Nuraghe Antigori’s production of Aegean-style wares and elsewhere the adoption of metallurgical techniques seem to mark the limit of the borrowing from the Aegean. As Lo Schiavo (2003b: 161) argues, when discussing Sardinia’s cultural elements, ‘none of these bears any similarity to either the Atlantic or the Aegean and Cypriot worlds.’ As for the involvement with peninsular Italy suggested by the amber imports, it is not until the EIA that the Nuragic objects in tombs in northern Etruria speak to close connections. Despite the evidence of extra-insular contacts, then, the Sardinians for one experienced little cultural change from them. Instead, we see new relationships with the material world emerging that point to internal social cleavages.

Sardinian goods leave the island in fairly limited quantities, although there is an intriguing corollary between Nuragic ceramic exports and oxhide ingot find sites, at Cannatello, Lipari, and Kommos. In the thirteenth century BC, Nuragic gray-ware pottery reached the site of Cannatello on the south coast of Sicily and the site of Kommos on Crete (De Miro 1999 for Cannatello; Watrous et al. 1998 for Kommos). At Kommos, the Nuragic pots were found spread across multiple structures in the settlement, in contexts of LM IIIA2 and LM IIIB date, leading scholars to conclude that the pots’ presence was not the result of a unique episode. At Cannatello, too, an oxhide ingot was found (Lo Schiavo 2003b: 153). In the FBA (1150–900 BC), Nuragic sherds turned up in several find spots on the Lipari acropolis, and Lo Schiavo (2006: 1328) suggests that they span a wider period than previously thought, pointing to multiple episodes of importation. There too, oxhide ingot fragments have been found, in the massive Lipari hoard that dates to the LBA or early FBA (Bernabò Brea and Cavalier 1980). Finally, at the end of the FBA and in the EIA, a particular class of Nuragic pot, the askoid jug, turns up at sites, particularly Phoenician ones, beyond the island (including Khaniale Tekke in Crete; Carthage; Carambolo in Iberia; Mozia on Sicily: Vagnetti 1989; Køllund 1998; Torres Ortiz 2004; Lo Schiavo 2005). These jugs have also been found in tombs at Vetulonia in west central Italy, though most may have been locally produced (Lo Schiavo 2003b: 154). Lo Schiavo suggests that the jugs may have had some religious function, as they are found in cult contexts on Sardinia and in tombs in Etruria, rather than forming part of domestic assemblages. Given the Iron Age date of these jugs, it would be ill-advised to group them with the earlier Sardinian finds, but they nevertheless illustrate yet another instance of Sardinian exports.

Overall, the quantities of Nuragic exports are small, and this is not a function of mere geography: the distribution of Sardinian obsidian in the Neolithic (Tykot 2004) shows consistent patterning in both source and destination, and points to an evolving and complex network involving, for example, targeted access to obsidian from particular sources at Monte Arci for groups living as far away as southern France. The two phenomena are difficult to compare given the vastly different time spans (3000 years of Neolithic obsidian exportation compared to 400–500 years for the LBA and FBA exports) and different circumstances. Nevertheless, we can gather that interactions with the mainland had occurred in earlier periods. While we may assume that some Nuragic exports go unnoticed because scholars working in other areas of the Mediterranean do not recognize them, if the quantities were significant enough, it seems unlikely that they would remain entirely overlooked. In the LBA and FBA then, far from being outward-looking, Sardinia’s residents for the most part must have purposefully refrained from establishing social relationships further afield, their attention focused inward as they invested old habits with new meanings.

These changes are embodied in the nuraghi themselves. The massive Nuragic complexes of the LBA exude an unambiguous sense of power and militarism. The wall separating them from the surrounding huts is clear evidence of the sharp distinction between those who occupied the nuraghi and the rest. These nuraghi must have been appropriated by the new elites as a sign of power over others and over a territory, thus detaching them from the majority of the nuraghi, whose social significance was quite different. This bifurcation of the buildings’ significance, when it had formerly been axiomatic, marks a radical shift. The nuraghe had come to serve two purposes: the complex nuraghi were symbols of power, while the single tower nuraghi continued to underpin an island-wide cultural identity. These new appropriations came at a price: the tension between these two claims to the nuraghi appears to have led to anxiety over their authenticity.

‘Authenticity,’ a slippery quality to define thoroughly, becomes of great importance only when it appears to be vanishing. Cultural and social disruptions, resulting in problematized identities, will lead to competing claims to authenticity, of both objects and people. When it comes to objects, the distinction between authentic and fake may be easy to grasp, but how may an authentic object or place become inauthentic? What had formerly been authentic may cease to be when it no longer possesses ‘original or inherent authority,’ to draw from the Oxford English Dictionary definition of authentic. Once something is recognized as an object whose meaning is alterable, it can be said to have lost its authenticity. The nuraghi in the LBA and FBA came to be appropriated by new elites as a symbol of power, and from then on there were two competing claims to these towers. This cleavage in the meaning of the nuraghi is evident by the EIA when the proliferation of models of the towers, in bronze and stone, speak to a new concern with recycling this image in varied ways (Blake 1997).

Conclusions

As we have seen, the notion of the LBA as a period of ‘extroversion’ on Sardinia may be overstated. But perhaps the earlier introversion of the EBA and MBA needs rethinking as well. The unusual megalithism is not unique to Sardinia: other islands in the central and western Mediterranean have similar buildings, most notably Corsica, Mallorca, Menorca, and Pantelleria (Camps 1990; Fernández-Miranda 1997; Tusa 1997). Each island’s buildings are different enough to show local inflections, but it seems very likely that their respective builders knew of the other’s constructions. In the case of Corsica and Sardinia, this is not surprising, as the two islands are separated by just 12 km of water, and their cultures had long been intertwined. However, that the residents of Menorca and the residents of Sardinia, some 385 km apart, were in contact requires more explaining. Likewise, Pantelleria is extremely isolated, and yet her sesi are not unlike a poorly built nuraghe. Thus, even the monument building need not speak to a period of isolation in any clear way. The island’s exposure to extrainsular contacts can thus be fit into a context of ongoing if sporadic interactions with other regions of the central and western Mediterranean, most visible in the insular monuments and the distribution of obsidian.

What the new waves of foreign contacts in the LBA and FBA allow us to do is see clearly the weaknesses of the Nuragic elites of that period. The fact that the inhabitants of the largest nuraghi, clearly with many people at their command, seem to have made no attempt to control the metals industry or the access to exotica may be a clue to the ultimate ‘balkanization’ of Nuragic society in the Iron Age and the abandonment of the nuraghi in favor of new dwellings. In the Bronze Age, Sardinia seemed to be on a trajectory toward a state-level polity, but the Iron Age saw no such coalescence into a supra-regional political unit. While there is evidence of wealthy Iron Age elites, perhaps a veritable aristocracy, from such sites as Monte Prama with its magnificent statues, these elites are no longer centered at the nuraghi, and there are no signs of a coherent political framework of territorial control on a large scale (see Perra 2009 for a reinterpretation of Nuragic political structure over time, and see Tronchetti and van Dommelen 2005 for a study of Monte Prama and its Iron Age cultural context). The Phoenician colonists to the island cannot be blamed for this, as van Dommelen (1998: 107–109) makes clear, because the eighth century BC did not see any hardships inflicted on the Sardinians from outside. Instead, it was the case that the Nuragic political authorities of the LBA and FBA had not sufficiently harnessed the economic opportunities offered by the foreign contacts, focusing on a traditional resource base of land and livestock. While they were at pains to appropriate material symbols of status and power, in particular the nuraghi themselves, the abandonment of the nuraghi in the subsequent period suggests that they were not successful. In the first millennium BC, trade and metals were sources of power, and while a new class of Sardinian elites benefited from interactions with the Phoenician colonists, the ‘old guard’ presumably did not. Cultural uniformity was not protection enough against outside threats: political and economic centralization were necessary, and these were missing. The island’s peoples could never achieve an island-wide state-level polity on livestock alone, despite their foreign contacts. While there is an appeal to the acephalous cultural cohesion characterizing Sardinia in the second millennium BC, it could not withstand the pressures of the first power to try to control it, Carthage, and although elements of the Nuragic culture lingered for many centuries, it would never enjoy the same level of political, cultural, or economic autonomy again.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Bernard Knapp and Peter van Dommelen for their editorial support and patience, and to Robert Schon for his comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this chapter. All errors are the sole responsibility of the author.