And say, “My Lord, lead me in through an entry of truth, and lead me out through an exit of truth, and grant me from You a supporting power.” And say, “The truth has come, and falsehood has withered away; for falsehood is bound to wither away.”

Holy Quran, 17:80–81

When I first got the e-mail I gasped slightly. Was this really … really, from the wife of comedian Chris Rock?

I got thousands of messages on my blog as I posted in response to Serial every week. Like Adnan, I couldn’t respond to everyone, but every so often a message would make me stop, force me to respond. It could be a message from someone offering to help with their expertise, or contribute to a fund for Adnan (which I had yet to even think about setting up), or sending a surprising, feel-good message thanking me for opening the world of Muslims to them in a way they hadn’t been exposed to before.

I was insanely excited when Jemima Goldstein, known as Jemima Khan to her legions of Pakistani fans, sent me a Twitter message. Jemima, the ex-wife of Pakistani cricket legend and current political leader Imran Khan, is the closest Pakistanis ever got to having their own princess. She’s adored by Pakistanis, even after divorcing Khan, having gained our admiration and trust for being an outspoken critic of the U.S. drone policy in Afghanistan-Pakistan as well as for her continued public concern for the people of the country. Jemima reached out to tell me she had listened to Serial and how impacted she was by Adnan’s story, especially given the fact that her own sons were teenaged Pakistani-British Muslim boys and Adnan reminded her of them.

I had already heard from Jemima when I got the message from Chris Rock’s wife. And yes, I initally thought it was the Chris Rock—it took a couple of days to realize it couldn’t be unless the comedian had a secret second wife stashed away in Australia. Still, I was really touched by her message, having gotten it on a particularly bad day when Internet trolls were doing a number on me.

I wrote back, and after a couple of weeks she made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. Dez’s Chris Rock was not only one of the most respected and well-known hackers in the world, he also ran one of the world’s premier cyber-security firms, Kustodian.

Would I like Kustodian, free of charge, to protect my blog?

Why, yes, Dez, yes. I would like Kustodian to do that.

Within a matter of weeks, they took over my site and began protecting it from literally thousands of attacks a week, something I could have never have managed on my own.

Shortly before I first heard from Dez, I got another note through my blog that made me pause. A literary agent wanted to speak to me. Lauren Abramo had been reading my blogs and following my other work too. She thought I should write a book.

After talking for a bit and realizing she was really, truly interested, I finally got excited.

“Can I send you what I’ve written, the start of a novel? I’ve got a few chapters down, it’s a story built on multiple stories from my life and the lives of people I’ve known—about a Pakistani girl who is married off by her family and ends up in the U.S. as an immigrant!”

Lauren grew silent, pausing cautiously as she tried to find the kindest way to break my heart.

“Well that sounds wonderful, Rabia, but I was thinking … perhaps you should write a book about Adnan’s case.”

It was my turn to pause.

I hadn’t ever considered writing about his case, and the very thought of it filled me with dread.

I was afraid that people would think I was trying to profit from the case. I had already heard that people were saying I was trying to ride the podcast’s coattails to fame, even though I hadn’t done any fund-raising and wasn’t even making money on my speaking engagements at this point. Later, because of the enormous demands on my time, I did begin asking for a small speaking honorarium, half of which I donated to Adnan’s legal fees.

I didn’t want to do it. It opened the door to the public considering me an opportunist, and maybe even Adnan and his family as well. But Lauren pointed out that if I didn’t a write a book someone else might.

I told her I’d think about it.

I also had to think hard about it for another reason: I didn’t know the case as well as she thought. I still had thousands of documents to review and would have to wait until Serial was over, until my project at New America was over, to really get through them. It could take at least a year to do that, and by then maybe interest in the case would be gone.

Little did I know that within the month, one of the sharpest minds I’ve ever encountered would enter the scene and save me.

On November 23, 2014, Susan Simpson, a lawyer I’d never heard of, put up a post on a blog I’d never heard of either, The View From LL2. I saw the link on Reddit and spent the next two hours carefully reading and re-reading the fifty-nine-page tome titled “Serial: A Comparison of Adnan’s Cell Phone Records and the Witness Statements Provided by Adnan, Jay, Jenn, and Cathy.”

I did a little quick Googling on Susan. Everything looked on the up-and-up—she was an associate attorney at a D.C. firm, the Volkov Law Group, and a law graduate of George Washington University. Her focus was on white-collar defense but she had a background in criminal appeals. Her previous few posts discussed maritime border laws and the Alien Tort Statute. It didn’t escape me that she had also made a suit of armor for her ridiculously fluffy kitten, Ragnarok. This, I realized, was a highly talented and multifaceted woman. And she loved her cat as much I cherished my feline Mr. Beans, who graced my social media regularly and had become familiar to my followers. I liked her.

Susan also had done what I had not had the time to do—taken every phone call made from Adnan’s cell that day and compared the “pinged” tower locations to every version of Jay’s, Jenn’s, and Adnan’s stories. It was meticulous and thorough, and showed that the State’s story at trial wasn’t actually corroborated by the records.

Sarah had mentioned on Serial that the State only brought up four of the fourteen sites it had tested that day because the other ten didn’t match up to Jay’s story. The four that could be used to bolster Jay’s testimony were all calls after 6:00 p.m., the most important ones being two incoming calls at 7:09 and 7:16—otherwise known as the “Leakin Park Pings”—because they were routed through a tower located in the park.

On these calls, Dana Chivvis concludes in Episode 5, “Route Talk,” that there is little equivocation. She believes the cell phone must have been in the park at the time the calls came.

Susan Simpson writes in her first post on the case, “Of the 52 outgoing and incoming calls made to Adnan’s cell phone on January 12 and 13, 1999, exactly two calls were routed through L689B, which is the tower and antenna that covers the southwest portion of Leakin Park (and covers almost nothing that isn’t Leakin Park). In fact, only one other call was even routed through tower L689, despite the fact it is adjacent to the towers covering Woodlawn and Cathy’s house—and that’s the 4:12 p.m. call, when Jay would have been parking Hae’s car immediately next to Leakin Park, at the Park-n-Ride. This is very strong evidence that the reason the 7:09 and 7:16 p.m. calls were routed from the Leakin Park tower is that the cell phone was, in fact, in Leakin Park. The odds are too much against this being a mere coincidence—because over the course of 48 hours, only two calls are routed through L689B, and both occur precisely within the one-and-a-half hour window in which we know the killer was in Leakin Park burying Hae’s body. This is a sufficient basis from which to conclude that the killer had the phone while burying Hae.”

Dana says something similar on Serial: “The the amount of luck you would have to have to make up a story like that and then have the cell phone records corroborate the key points, I just don’t think that that’s possible.”

The Leakin Park calls were the bane of my advocacy for Adnan, the only thing I didn’t know how to rebut.

The thing I could easily rebut, the issue Sarah thought most damning for Adnan, was the call made from his phone at 3:32 p.m. to Nisha Tanna, the young woman he had begun talking to after breaking up with Hae. Who would be calling Nisha in the middle of the school day from Adnan’s cell phone but Adnan himself? Sarah asked. She figured that put Adnan with Jay at a time when Adnan said he wasn’t with him, and at a time around when Hae went missing.

The “Nisha Call” was easy—Jay said Adnan called her after killing Hae, then gave Jay the phone to briefly chat with her too. Nisha also testified that she did indeed speak to Jay just once while on a call with Adnan—but she stated with specificity that this chat took place when Adnan went to visit Jay at a video store he was working at. The “Nisha Call” couldn’t have have happened on January 13 though, because Jay didn’t begin working at the porn video shop until January 31.

Nisha’s number was saved on speed-dial on Adnan’s phone. It was likely called on January 13 by mistake—a butt-dial or otherwise mistaken attempt to make a call by Jay, because he still had the phone at the time and all calls before and after the “Nisha Call” were to Jay’s friends.

But the Leakin Park calls were different. According to Adnan, he was with Jay after school that evening. He had dropped Jay off at home at some point, and then headed to the mosque for evening prayers. Without a doubt, whether or not Jay was with him at 7:00 p.m., the phone definitely was. And if the phone was in Leakin Park when Adnan had it, we had a problem.

Susan’s next post was a few days later, where she examines Jay’s credibility and concisely articulates why he has none: because he himself admits it.

“But sometimes, it is very easy to make an assessment of a witness’s inherent credibility. And that is when a witness informs you that he has none. Jay is that witness. Jay told the police and the jury, again and again, that he was willing to lie in order to avoid criminal punishment. He was not shy about this fact. Ask Jay why he lies, and he’ll tell you: he lies because he didn’t want to get in trouble.”

Susan then challenges Sarah’s agreement with the State, that while there have been some “inconsistencies” in Jay’s story, the “spine” of his story has remained consistent.

“Wait, what?” Susan writes, “Jay tells a ‘consistent’ story? Jay has been ‘consistent’ on the main points? Koenig keeps using that word. I don’t think it means what she thinks it means.”

Susan spends a dozen pages listing the dozens of times Jay’s story has been inconsistent. As I’m reading this, I’m thinking, Who is this woman?

I had to reach out. On November 26, 2014, I e-mailed her.

“Dear Susan, I’ve been reading your blog about Adnan’s case and wanted to reach out to thank you for your tremendous work. I was going to, at the end of Serial, plot out Adnan’s timeline as per my theory and understanding that day/evening, and you did it almost exactly as I was going to. I’m in the D.C. area too, perhaps we can get together sometime. I’d love a partner in crime on this. All the best, Rabia.”

Susan wrote back the next day.

“Hi Rabia! As I’m sure you’ve noticed from the several documents/sources I stole from you, I’m a fan of your blog. (Am also a fan of Mr. Beans.) And I would be more than down for getting together sometime—I gotta admit, the narrative framework of Serial has been really frustrating sometimes, because there’s just a complete absence of any legal perspective. I’d love to hear about the case from someone with a lawyer’s view.”

I was stoked and had already decided that I’d give her access to the files. I needed her eyes on them.

* * *

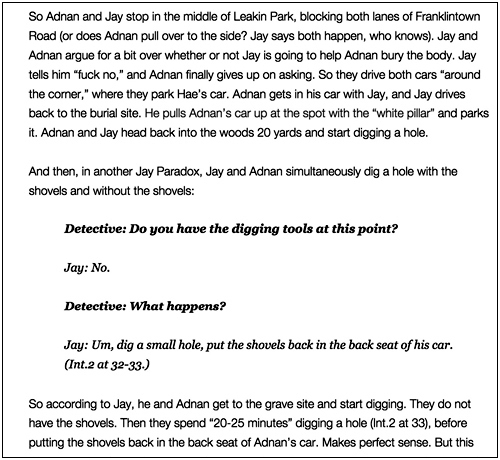

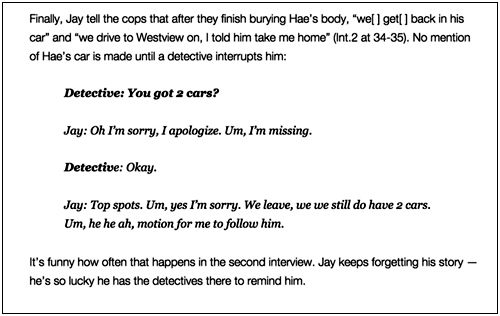

Susan’s next post, on November 29, titled “Serial: Plotting the Coordinates of Jay’s Dreams,” masterfully showed the impossibility of Jay’s statements like this:

From Simpson’s blog viewfromll2.com

And this:

Shortly after I made contact with Susan, I got a message from someone else I’d never heard of before, a man named Colin Miller.

On December 3, 2014, Colin wrote to me to share a blog he had written about the cell tower evidence in the case. Not having the trial transcript, Colin had questions about how things had transpired when the judge nearly excluded Abe Waranowitz as a cell phone expert. I took a look at the blog post he sent me and then did some background research on him.

Professor Colin Miller, I discovered, taught criminal law, criminal adjudication, and evidence at the University of South Carolina School of Law. But he wasn’t just an evidence professor, he was the evidence professor, writing and editing a blog called, aptly, The EvidenceProf blog.

By the time Colin reached out to me, he had already done eight posts on the case and Serial, beginning on November 21, 2014. This was an incredibly prolific blogging rate by any standard.

I began following him and Susan and eventually realized that I needed to give them both the full case files—they both had the drive, time, experience, and brain power I lacked to analyze what had happened. What Sarah wasn’t able to find, what I wasn’t able to find, maybe they could.

It couldn’t have come at a better time because Serial was wrapping up. Sarah had told me there would be twelve episodes and by my count, in early December, that meant the end was around the corner.

Here was the real test: How would Sarah conclude on his guilt or innocence? Where would a year of getting to know Adnan leave her?

Eleven episodes of Serial had carefully kept listeners on the fence about Adnan’s guilt or innocence; maybe, we hoped, she was saving her big reveal for the last episode. Maybe she would come out and say what she hadn’t so far, that she believed in Adnan’s innocence.

A couple of weeks before the last episode Sarah and I met in my parents’ basement, not far from Adnan’s home. She recorded our conversation for about an hour, asking how I felt knowing that she had found nothing to fully exonerate him. At that point I knew there would be no big surprise at the end of the podcast.

Fine, there was no hard-and-fast proof. But what about Sarah herself, what did she think? Surely her opinion would count for so much. Unlike her listeners, she had spent time with Adnan. I didn’t want to put her in a tough spot, but dammit, after all this time I wanted to know. So I finally just summoned up the courage and point-blank asked.

“In my heart,” she said, “I think he’s innocent.”

She had no proof, of course, but for me it was enough to hear those words from her lips. I felt a rush of relief, and after she left I told Yusuf, Saad, and Adnan what she said, reassuring them that the podcast would end in Adnan’s favor.

The morning of the final episode, December 18, 2014, was tense. I couldn’t wait to hear Sarah’s conclusion but also couldn’t wait for the podcast to be over so we could focus on the actual case and bringing Asia back into it. But first there was a big surprise in the episode—out of the shadows came a person no one expected to hear from: Don Clinedinst.

When Sarah was researching the case, she had reached out to Don, and he had refused to talk to her. Then, a week before the final episode was taped, having perhaps listened to the previous eleven episodes, he contacted her and agreed to talk but not to be recorded.

I had not, in all these years, given Don a second thought. The first time he crossed my radar as a possible suspect was when I heard Deirdre Wright of the Innocence Project mention him in Episode 7. Even then, though, I figured he was part of the “big picture” excuse Deirdre thought we’d need to get a court to allow us to retrieve whatever DNA evidence may exist, nothing having been tested against Don or anyone other than Adnan and Jay all those years ago.

In the blog post I wrote after the Innocence Project episode I didn’t even mention Don, but after the last episode, in which Don speaks to Sarah but refuses to have his voice recorded, I wrote a few paragraphs about him, mostly focused on entirely the wrong thing:

“Ok, I’ll just be up-front here. I don’t know what to do about Don. The note to him really weirded me out.”

I was referring to the note found in Hae’s car, the note addressed to Don in which she tells him to drive safe and that she has to run to go to a wrestling match at Randallstown High. The question I raised in my blog was when and why Hae would have written that note, because some of the language, “sorry I couldn’t stay,” suggested she had already seen him on the day she wrote it.

And the day she wrote it, by the State’s accounts and as accepted by Sarah, was January 13, 1999, the same day Hae was killed.

Others dismissed the language as being ambiguous, that perhaps Hae was in a hurry and didn’t express herself clearly. For most, the note indicated she intended to see Don that night. But that didn’t sit right with me; it just didn’t make sense.

Hearing Don’s words about how he knew he’d be a suspect immediately and began recounting his steps raised my eyebrows. On the one hand you had Adnan, who was so clueless that even as police kept interviewing him he didn’t give it a second thought, dismissing the idea as absurd.

And here you had Don, about whom Sarah said the following:

When Hae went missing, Don was one of the first people the cops called. He says he knew immediately he’d be a suspect. “I said, ‘well ok, they’re going to try to blame it on me because she was with me last night. I’m the new boyfriend, I’m obviously going to be one of the first suspects, me and Adnan.’” He said he immediately made sure he knew where he was. “When someone calls you up and tells you ‘have you seen this person? They went missing, they haven’t been seen since school,’ you automatically retrace everything you did that day.”

I found Don’s reaction deeply unsettling. In no universe, if my partner couldn’t be located, would I begin retracing my own steps. I’d be worried sick, focused on finding that person. But I had to acknowledge that this may not be true for everyone.

The police had definitely done a shoddy job during the investigation by not confirming through paperwork that Don was really working on January 13. Despite such a glaring investigatory breach, any questions about Don could be put to rest since LensCrafters had eventually turned over his timesheets to Gutierrez prior to trial. Don was definitely at work that day, and the police considered his alibi airtight.

After Don, Sarah spoke with a former co-worker of Jay’s, a man named Josh. Josh recalled Jay being terrified, paranoid about a van outside the porn shop. Josh figured Jay was scared that Hae’s killer was in the van, though Jay never mentioned that someone being Adnan.

Sarah asks Josh if Jay is scared of Adnan’s “people,” of Pakistani relatives, and Josh says, “Yeah, he definitely said it was somebody, the guy was Middle Eastern.”

Josh goes on to speak warmly about Jay, saying he feels sorry for him and that Jay wasn’t a thug, rather the opposite, and he seemed in way over his head.

Before her conclusion, Sarah asks for Dana’s take on the case. Calling her the “Mr. Spock” of the podcast, Sarah lets Dana lay out her thought process in detail, which boiled down to this: in order for everything to make sense, that Adnan just happened to lend Jay his car that day, and Jay happened to turn witness against him, and there happened to be a call to Nisha that afternoon, and Adnan happened not to have an alibi or even remember where he was—well, he’d have to be the unluckiest man ever. And no one is that unlucky.

Only after this buildup, and a brief interlude from Deirdre about a possible lead and where they were on seeking to test the forensic evidence for DNA, did Sarah get to her big ending.

To the disappointment of many, certainly all of us, Sarah wasn’t able to commit herself to Adnan’s innocence. She said she wouldn’t have convicted him because there was too much reasonable doubt, and that while most of the time she thought he was innocent, she still “nursed doubt.”

I can’t fault Sarah for reaching this conclusion, and neither does Adnan. Unlike myself, Saad, and Adnan’s family, Sarah has no reason to put her credibility and her professional reputation on the line for a cause she didn’t have full confidence in.

After Serial ended, Sarah assured Adnan that she would continue to follow the case. While it wasn’t an endorsement of his innocence, it was good enough for us.

* * *

Sometime in the middle of December 2014, right around the last episode of Serial, I was asked by a friend how to donate to Adnan’s legal fund.

“What legal fund?” I asked.

“Um, you didn’t set up a fund? Wait, you let all of Serial go by and didn’t do any fund-raising? Doesn’t he need money to help with legal fees!?”

Indeed. Yes he does. Except I hadn’t had a chance to even think about it.

There wasn’t any money, there was no fund. Adnan’s parents had paid out of their modest means for years, all throughout the appellate process, and it had taken almost five years to raise the money for the original post-conviction. After the PCR was denied in 2014, although Justin had been ready to finally step away from the case after representing Adnan for five years, he was now fully in again. Serial and the return of Asia meant he would continue to push Adnan’s appeal whether or not he got paid, he told Adnan.

But it wasn’t just about Justin’s legal fees. It would be incredibly generous if he waived them, but it would not be fair considering the tremendous amount of work he had to put in. It was also about other expenses we anticipated, such as hiring a private investigator in the hopes of uncovering new evidence.

I knew we had to raise money, I just didn’t have the mental and actual bandwidth to deal with it.

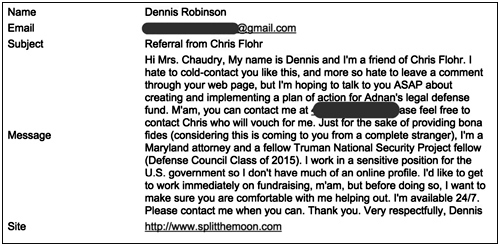

Then I received this e-mail from Dennis Robinson:

Chris and I had been discussing how to go about the fund-raising, and at some point he must have realized I needed help.

I connected with Dennis as soon as possible.

“You take care of speaking up for Adnan,” he told me. “I’ll take care of everything behind the scenes. I’ll be your assistant, set up the fund-raising, manage the communications, whatever you need.”

I cried for a couple of days, tears of happy thanks. Before I knew it, Adnan’s crowd-sourced fund-raising site was up on LaunchGood.com, which went out of its way to get the account set up and promoted within a matter of days. And the donations began pouring in.

Between Dez, Dennis, Susan, and Colin, it was as if angels had been sent to lift all the burdens I wasn’t capable of carrying. The podcast was over, but the quest continued. I had to figure out how to keep public interest in the case, had to figure out how to put pressure on the State and courts to help with the appeal, and had to figure out what actually happened to Hae.

Fighting Adnan’s case in court based on Gutierrez’s failures, coupled with Asia’s allegations, seemed possible now. But without returning to the original evidence, and getting the people at the heart of the matter to talk, getting to the truth of what happened to Hae would be much, much harder.

Some people, friends from school, tried to talk to Jay and get him to come clean. But he was angry at the attention, at his life and family being disrupted. He was married with kids now, living in California, far away from it all. He told some people that strangers had located his home and driven past it, taking pictures, posting his address on Reddit, and he was (justifiably) pissed off.

But at the end of December the universe sent us a big, fat gift. Jay talked.

I was in Canada, visiting my in-laws, relieved that Serial was over and I could take a break. Sometime in the afternoon of December 29, 2014, I got a text from Saad.

“Jay did an interview! He said he lied, it’s so effed up, read it Rabia!!!”

Within a matter of minutes the interview, written by Natasha Vargas-Cooper for The Intercept, was tweeted, texted, and e-mailed to me a dozen times. I pulled myself away from my mother-in-law and locked myself in a room so I could read it in peace—except I couldn’t, not in peace anyway.

Every paragraph made me livid. From when he first met Adnan, to his ridiculous story of being a serious drug dealer, to admitting that he and Adnan were never friends, to completely changing the narrative of the crime, I was shocked at the ease with which he lied and transformed his story.

I couldn’t get through it without tweeting my immediate reactions. I screenshot nearly every paragraph and tweeted them with exasperated comments like “#PerjuryAbounds!”

Every part of Jay’s story had changed. Now he didn’t know if Hae had been killed in the Best Buy parking lot, and he also never saw Hae’s car there; he just picked Adnan up there after the deed had been done and didn’t know where her car was. The entire ride sequence when they supposedly drove around looking for a place to leave Hae’s car, the Park-n-Ride—poof, it was now gone.

Jay says after picking Adnan up, they went to Krista Vinson’s house, referred to as “Cathy” in the interview since she was called “not-her-real-name-Cathy” in Serial, where, surprise, Jenn is present. He says it’s between 3:00 and 4:00 p.m.; they hang out, smoke weed, and Adnan drops him home at 6:00 p.m. Track practice is gone. And gone is Leakin Park in the 7:00 p.m hour.

It gets more interesting. Jay says after dropping him off at home, Adnan returned with Hae’s car to his grandmother’s house and called Jay on the landline (there is no such call in the call records). Adnan then popped the trunk on the side of the road, showing him Hae’s body. According to Jay, “she looked kinda purple, blue, her legs were tucked behind her, she had stockings on, none of her clothes were removed, nothing like that. She didn’t look beat up.”

This, despite the fact that when Hae was disinterred, her bra and shirt were pulled up, exposing her breasts, and her skirt was pulled above her buttocks.

Standing at the open trunk, Adnan asks Jay to just help him “dig the hole.” Jay agrees after Adnan threatens to turn him in for dealing weed, as if it is a much more serious crime than accessory after the fact to murder. Then Adnan drives off with car and body.

But the night is not over. Adnan returns a few hours later, close to midnight, in his own car. This time he’s back to make Jay keep that promise, but first he needs tools to dig the hole. Jay grabs some gardening tools and they go to the park, where Adnan presumably pulls over by the side of the two-lane road as it begins to rain (there was no rain on the night of January 13, 1999). Jays says: “We dig for about forty minutes and we dig and dig,” until Jay finally says “fuck it” and is done digging.

They have their hole, but no body. The body is apparently still in the trunk of Hae’s car, which according to Jay is up around the bend on a small hill, “parked in a strange neighborhood”—strange, despite the fact that it’s the same neighborhood where one of his grandmothers lives.

They drive around the corner, up the hill, where Adnan gets into Hae’s car and tells Jay to move his car “halfway back down the hill” so that after burying Hae, Adnan doesn’t have to walk too far to get to his car. Why he would have to walk to get to his car is unclear, since he would have Hae’s car.

Nonetheless, according to Jay, Adnan drives off with Hae’s car but then returns after thirty to forty-five minutes on foot to his own car, where Jay waits for him. He says Adnan is wearing gloves, panting, saying Hae was heavy. Gone now is the entire portion of Jay’s police statements and testimony in which he is sitting on a log while Adnan digs. In this new version, Jay never sees Hae in the grave at all, despite having described her position in some detail sixteen years earlier.

There is still the problem of leaving Hae’s car somewhere, but apparently Jay must first drive Adnan back down the hill to get it. Jay says he then follows Adnan around (presumably Adnan is in Hae’s car and Jay is in Adnan’s car) for a “few minutes” and dumps the car behind some row houses.

Jay goes on to say that it took intense pressure for the police to get him to cooperate, and it was only after getting assurances that he wouldn’t be prosecuted for “procurement” of weed that he agreed to talk.

The next day, December 30, the second part of the interview was published. Again, my hackles and ire were raised sky-high, especially when Jay mentioned the grand jury hearing and testimony of a “spiritual advisor” whose name starts with a “B.” Bilal. He had to be talking about Bilal.

According to The Incercept article, “He spoke with the police during the investigation. But when he was called to the grand jury, he pled the fifth [the fifth amendment, that is, against self incrimination through testimony]. So that whatever he knew about Adnan, he knew that if he said it in court he could also be in trouble.”

The editors of the piece inserted this note: “The Intercept confirmed with two sources that ‘Mr. B.’ did plead the fifth during the grand jury testimony.” This is odd and not at all accurate. Bilal and Saad, thanks to the counsel and direction of Gutierrez, filed motions to quash the State’s subpoena calling them to testify, wherein they said they would “plead the fifth” if called. The motions didn’t fly and both of them testified; in other words, they did not plead the fifth.

So not only was Jay wrong about this but the editors of the piece somehow confirmed the incorrect information as accurate, leaving people to believe Bilal hadn’t testified. I was also struck by how Jay knew anything about who had testified at the grand jury—the proceedings were sealed, and there is no public access to the records. Someone from the State had to have told him, either sixteen years ago, or now.

I was a bit perplexed by all of this, and also by Jay’s antagonism toward Sarah in the piece. He believed she had damaged his reputation. But overall I was thrilled with the interview, because Jay had basically undone the entire State’s narrative, including his own testimony at trial. The interview was so damaging that Colin Miller was even quoted in a piece on Vox.com: “I said before that the prosecution’s case was dead. With this interview, Jay has now burned the corpse.”

I didn’t know the reporter or her angle, but I had tremendous respect for The Intercept, which was known for its exhaustive investigative reporting. I thought it was pushing the envelope to publish the exchange between Jay and Sarah, which they did in full, but the exchanges weren’t damaging to Sarah; if anything, they undermined Jay’s allegations.

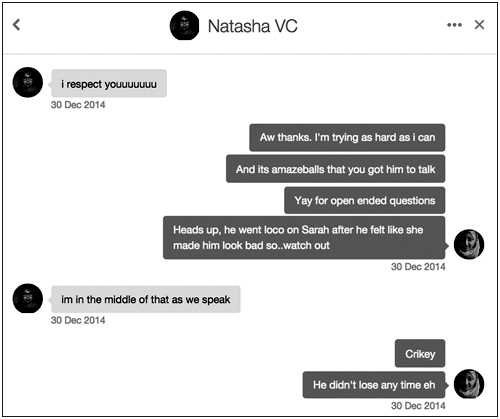

After the second part of Jay’s interview, I got a message from Vargas-Cooper, who I like to refer to as “NVC,” through Twitter.

Apparently Jay was already having a similar reaction to NVC as he did to Sarah. I wished NVC would tell me more about how he was acting, but I didn’t ask. We exchanged a few pleasantries, but then she gave me, in retrospect, a warning when she said, “It’s going to get gnarly in the coming week, regardless of what I think, just know I think you’re an ass kicker.”

I had little reason to think that NVC was going to completely flip the script with what was to come: an interview with Kevin Urick.

Part one of the Urick interview was published on January 7, 2015. But it wasn’t just an interview with him. It began as an opinion piece, with NVC making it clear that she had no respect for Sarah and the work of Serial. I realized with a slow sense of dread why all of Sarah’s e-mails to Jay had been published.

In the prelude to the interview NVC writes:

“Serial” portrayed the case as a combination of overzealous prosecution and incompetent defense counsel. This viewpoint infused the entire podcast. While Koenig never proclaimed Syed to be innocent, she insisted the evidence didn’t support his conviction. “It’s not enough, to me, to send anyone to prison for life,” she said in the closing of the last episode.

When a jury of 12 people comes back with a guilty verdict in two hours, you’d think that rejecting their decision would require fresh evidence. Yet the show did not produce new evidence, and mostly repeated prior claims, such as an unconfirmed alibi, charges of incompetence against Adnan’s deceased lawyer, and allegations that information derived from cellphone records is unreliable.

None of these charges has survived scrutiny. That was the conclusion of a circuit court judge, who dismissed a defense motion that claimed such issues compromised the fairness of the trial. Nevertheless, the ‘Serial’ series largely mirrored the defense petition.

NVC goes on for a few more paragraphs attempting to prove Sarah’s bias by showing she made little effort to contact Urick for the series—a charge I knew was wrong because Sarah had told me how hard and how repeatedly she had tried to get Urick—as well as detectives Ritz and MacGillivary—to talk.

NVC goes further, stating with finality, “The justice system in America frequently doesn’t work. This is not one of those cases.”

I was gobsmacked, but not alone. Almost immediately I got a message from a source at The Intercept. It read: “I am so disgusted by the story today … it is a horrid malpractice justice wise and journalistically. Just awful pro-prosecution garbage. The story was awful.”

NVC and The Intercept were getting hit left and right in social media over her embarrassingly strong defense of the State and her obvious dislike (professional jealousy maybe?) of Sarah and her listeners, who in an earlier interview with The Observer NVC called “delightful white liberals who are creaming over This American Life.”

Not much was surprising in Urick’s interview; the prosecutor stood by his conviction.

Urick alleged that Gutierrez had initially submitted a witness list of eighty people to verify that Adnan was at the mosque on the night of the 13th, but “when the defense found out that the cellphone records showed that Adnan was nowhere near the mosque, it killed that alibi and those witnesses were never called to testify at the trial.” NVC fails to note that this statement is unsubstantiated.

Urick weds himself even more closely to the cell phone records, which may later come to haunt him, when he is quoted in the article as saying, “Jay’s testimony by itself, would that have been proof beyond a reasonable doubt? Probably not. Cellphone evidence by itself? Probably not,” but when put together “they corroborate and feed off each other—it’s a very strong evidentiary case.” He also says that “once you understood the cellphone records—that killed any alibi defense that Syed had. I think when you take that in conjunction with Jay’s testimony, it became a very strong case.”

I was squirming as I read this. How did NVC fail to ask Urick about Jay’s new, improved, and completely changed timeline?

When NVC asks about Asia’s potential as an alibi witness, Urick gives the same answer as before: Asia was being pressured by Adnan’s family.

Urick doesn’t know yet, no one in the public knows yet, that Asia heard him say all this on Serial and is ready to rebut under oath. He doesn’t know that she is now working with Justin Brown to get a new statement in court.

A couple of days after the Urick interview, I had a dream. I was sitting in a room, not sure where, but around the corner was the bathroom. I saw that the light was on in the bathroom and heard a noise. I went to explore and found a young boy, maybe around ten years old, in a tub full of water. The boy had been left there, forgotten. It was Adnan.

He sat there, shivering and just looking at me, unable to move without the permission of a grownup, waiting for someone to come get him. I grabbed a towel, pulled him out, and wrapped him up.

It was the third time I had dreamed about Adnan. It left me a bit shaken but hopeful. I felt like the dream was a sign that Adnan was no longer forgotten, that he was close to being rescued. The possibility of getting him home was closer than ever. And I felt that between Asia and the Innocence Project, 2015 was going to be a very bad year for the State of Maryland.

* * *

Deirdre Enright at the Innocence Project was drafting a motion to request that the court order the case forensic evidence be submitted for DNA testing. The first time I spoke to Adnan about it, in late January of 2015, he sounded excited but weary.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“I’ve been waiting for an opportunity like this forever, but now I don’t know what to do. Deirdre wants to push forward with the motion. Justin is saying not to do it. Who do I listen to?”

I had no idea that Justin and Deirdre disagreed, but any time more than one attorney is on a case there is always the possibility of egos, agendas, and strategies clashing.

My communications with Deirdre were limited; I knew she had her own investigatory team and was pursuing leads independently, and I didn’t want to interfere. But Adnan was asking for my advice, so I had to figure out what was going on.

* * *

I gave Justin a call to sort things out, and he made his case: On January 20, 2015, Justin had filed a new affidavit by Asia as an addition to the existing request to the Court of Special Appeals. The affidavit affirmed everything she had stated in her letters and earlier affidavit, explained what happened when she contacted Urick, stated that she wasn’t pressured to make any of her statements, and asserted that if given the chance again, she would come to court to testify to all these things in person. On the same day, TheBlaze, Glenn Beck’s Web site, published an exclusive on the new development, including both the new affidavit and an interview with Asia and her attorney.

The interview, affidavit, and new filing filled the airwaves, hitting the public (and we hoped the State) like a ton of bricks. The overwhelming coverage was a good sign; it meant that it would be hard for the court to ignore. The State opposed the filing a week later, asking the court to strike the new affidavit, but then Justin responded to the State’s motion. We all knew it was a long shot, but Justin believed Asia’s statement was strong grounds to reopen the PCR proceedings, hoping the court would be as incensed as the rest of us with Urick’s behavior. Colin worked with Justin to get the legal research and language of the filing together.

Given these developments, Justin believed it was worth waiting to see what the court did before moving ahead with the DNA.

He explained that if the PCR didn’t fly, then we still had the forensic stuff, the possible DNA to test. The truth is, he said, we don’t even know if anything still exists in the police locker; all that physical evidence could be gone. Or, if it’s there, it might not yield anything. In fact, it was likely we wouldn’t get anything out of it. So if we moved forward with the DNA and it gave us nothing, the State would have an advantage and less incentive to negotiate. But if we held off on the DNA and focused on winning the PCR appeal, the DNA kind of hung like a sword over the State’s head and also gave us one more bite at the apple if we lost.

Deirdre was adamantly against this strategy. Her plan was to get the DNA tested, show that it either matched someone else or didn’t match Adnan, and file a writ of actual innocence immediately. She believed the PCR didn’t have a chance. And she said so publicly, which undermined Justin and left us a bit disconcerted. Tensions ran high as we waited for the court to rule on whether we could appeal the PCR denial, and there was little communication between the attorneys. Deirdre was already speaking to state officials about filing the motion, and it seemed like she was going to go ahead whether or not Justin agreed. She just needed Adnan to say yes.

I called Deirdre and tried to explain Justin’s perspective. He wasn’t saying we should ditch the DNA petition altogether; he was just being his usual extremely cautious self and asking that we wait to see how the PCR appeal went. Along with Justin’s strategy it was fair to say that Adnan, his family, Saad, and I all had slight misgivings, a touch of fear about the DNA testing. It wasn’t unheard of that DNA could be tainted or tampered with, and I didn’t trust the Baltimore City Police or the State’s Attorney’s office for a hot second.

Deirdre stood by her conviction that the PCR appeal was doomed and that we were wasting an incredible opportunity by not focusing on the DNA immediately.

I wrote to Justin to let him know she wasn’t on board with waiting the PCR appeal out.

Justin said it was up to Adnan.

Adnan was nearly in tears. He knew if he told Deirdre to put a hold on the DNA, she would likely back out of the case altogether and he would lose the Innocence Project.

I told Adnan that if I was in his position, I’d let his lead counsel make all the legal decisions, period.

It was a good thing too, because on February 6, 2015, two days after talking to Deirdre and three days after Justin’s response to the State, the Maryland Court of Special Appeals granted our application. We could appeal the denial of Adnan’s post-conviction petition.

Justin’s gamble paid off. Asia’s new statement hadn’t been thrown out; we were back in the game. The appeal was full steam ahead now.