Know that if the whole world gathered together to help you,

they could not unless God had decreed so.

And if the whole world gather together to harm you,

they could not unless God had decreed so.

The pens have been lifted, and the pages have dried.

Prophet Muhammad, Sunan al Tirmidhi

The jurisdiction of the Baltimore County Police Department (BCPD) is a full 612 square miles, surrounding the City of Baltimore, and it has ten precincts. The Woodlawn Precinct 2 is on Windsor Mill Road.

Officer Scott Adcock wasn’t assigned to Woodlawn. He was assigned to the 3rd precinct, Garrison (now called Franklin), and he was out on routine patrol on the afternoon of January 13, 1999. Around 6:00 p.m. he was dispatched to a local home to respond to a call about a missing girl, Hae Min Lee.

When he arrived at Hae’s home, Officer Adcock met with her fifteen-year-old brother, Young Lee. The officer made note of Hae’s routine and her car model, and then asked for relevant telephone numbers. Adcock called the LensCrafters store in Owings Mills, where Hae was scheduled to work that evening, then called Aisha Pittman, Hae’s best friend. Hae’s mother had called Aisha earlier looking for Hae, and Aisha reached out to other classmates and friends—Becky Walker, Krista Meyers, and Adnan—to ask about Hae. No one had seen her.

The officer then attempted to get in touch with Hae’s new boyfriend, Don. Young had retrieved Hae’s diary from her bedroom (she knew her brother snuck peeks at it) to look for clues about her plans that evening and for Don’s number. Young dialed a number scribbled on her last entry from the night before. But Don didn’t pick up the phone, Adnan did.

Young initially assumed he had reached Don, and when he realized that he had actually called Adnan, handed the phone to the detective.

Adnan recalls the phone call, and that it was in the evening, after school. Aisha had already called him to tell him Hae’s family was looking for her and that she had spoken to a police officer. Officer Adcock asked Adnan if he had seen Hae and Adnan replied that he had seen her at school but not since. Adcock asked Adnan for his date of birth, address, and full name.

Adnan was high when he got the phone call. After breaking his Ramadan fast with a quick bite, he had lit up. He remembers feeling panicked at speaking to a police officer in this condition; he thought maybe the cop would want to meet him while he was high as a kite. But he didn’t. He had other calls to make. The call to Adnan was brief: there were three incoming calls to Adnan’s phone around six o’clock that night, two less than a minute long, and one lasting a bit over four minutes. Adcock’s call was one of them, but there is no way to verify which one because no one—not the police, prosecution, or defense—ever retrieved the incoming call numbers in his call records.

Adnan remembers another detail: when the phone rang, he reached over from the driver’s seat to get his cell phone from the car’s glove compartment. He wasn’t alone. He had to reach past his passenger, Jay Wilds.

* * *

It always seemed strange to me that the police would open a missing person’s investigation for an eighteen-year-old with a car, pager, job, and new boyfriend within hours of her disappearing. After all, Hae was technically an adult. In fact, as of 2005, numerous jurisdictions in Maryland did mandate a twenty-four-hour waiting period before accepting adult missing person’s reports. This was eventually changed through legislation that banned all such waiting periods throughout the state, a change unrelated to Hae’s case.

While such a waiting period may not have been the Baltimore County Police Department’s procedure in 1999, filing a missing person’s report within two hours—even before the police had spoken to Hae’s current boyfriend—seems highly unusual. But roughly seven months prior, another eighteen-year-old girl had disappeared from Woodlawn and been found killed.

Jada Denita Lambert disappeared one day on her way to work at a local mall. She was found when an anonymous call to 911 alerted the police that there was a young woman’s body in a shallow stream in Red Herring Park in the northeast part of Baltimore City. Jada was fully clothed but missing all of her personal property. An autopsy would later confirm she had been raped and strangled.

At the time that Hae disappeared, Jada’s murder was yet unsolved. On the one hand, fear of a serial killer may have prompted a quick response by authorities to Hae’s not showing up. On the other hand, Jada disappeared in Baltimore City. Her case was never with BCPD, so maybe the County Police never even knew about her.

Original missing person’s report

According to Adcock’s testimony, the rest of his evening was devoted to filing the necessary paperwork for the case and trying to connect with Don.

The report prepared for that evening’s activities identifies Hae as “victim,” another thing that has always struck me as odd this early on in a case.

Back at headquarters that evening Officer Adcock enters Hae’s information from the missing person’s report into the NCIC, the National Crime Information Center, a massive FBI-run database.

But Adcock makes a mistake; he fails to enter Hae’s car information from his written report. These are vital details. After all, Hae disappeared along with her car.

Around 1:30 a.m. on the 14th, about ten hours after Hae disappeared, Officer Adcock is finally able to reach Don.

The report is extraordinarily short. It reads, “I spoke to victim Lee’s boyfriend Mr. Donald Robert Clinedinst III, DOB [redacted], M/W. Mr. Clinedinst advised that he does not know the whereabouts of Ms. Lee. Mr. Clinedinst advised that he talked to Ms. Lee last on 1/12/99. It should be noted that I spoke to Mr. Clinedinst on 1/14/99 at 0130 hours.”

An additional report taken by another officer notes that Don had not seen Hae since January 12th, a slight difference from Adcock’s report, which notes they hadn’t spoken since then. Still, there are no details as to Don’s whereabouts on that day, whether he and Hae had plans to meet, and neither report mentions that he spoke with Hae into the early morning hours of January 13th, though that may be what he meant when he said he spoke to her on the 12th. After the conversations the police do not go meet with him.

By 2:30 a.m. on the 14th, the parking lots of local hotels, motels, and high schools have been searched for Hae and her car, and the sheriff’s office of Harford County, the county where Don lives over thirty miles away, has also been alerted with requests to check the area for her vehicle. But no clue as to her whereabouts emerges.

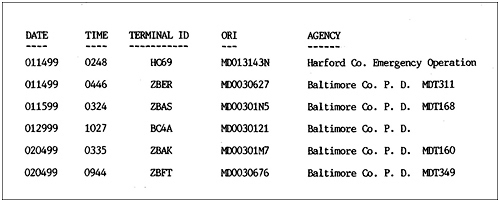

At 2:48 a.m. Hae’s car plates are run through the NCIC system, something that generally happens in two instances: a patrol officer runs the plates of a suspicious car he or she spots, or because the officer, having been alerted to keep a lookout for a car with these plates, uses the query as a method to “save” the plate numbers on their system. The query can be run two ways, through mobile terminals that are actually in the patrol cars themselves, or by calling into headquarters and having a dispatcher run the plates for you.

The 2:48 a.m. query was run through the Harford County Emergency Services dispatch in response to a “Be On the Look Out” (BOLO) alert from BCPD; a second query run through the NCIC system came from a Baltimore County terminal at 4:46 a.m. Over the following two weeks, Hae’s plates will be run through the NCIC system four more times, all from Baltimore County Police terminals.

The six times Hae’s license plates were run through the NCIC system

The first two times the plates are run, it seems certain that they were in response to the BOLO; but the last two queries run on her plates, both on February 4th, seem to indicate something else entirely. Not just to a layperson, but also to law enforcement officers who reviewed the data. The checks are done a number of weeks after the original BOLO was issued, which means they were probably not run in order to “save” the numbers. They are also done by two different mobile terminals, at 3:35 a.m. and 9:35 a.m. respectively, which raises the likelihood that two different police officers on consecutive patrols came across Hae’s vehicle and ran the plates.

If that is actually what happened, the tragedy of it is that these officers would have gotten no indication that this car was connected to an investigation. Those queries would have returned nothing. Adcock’s failure to enter Hae’s car information from the missing person’s report into the NCIC system means there was no alert connected to her tags.

It won’t be until February 10 that the database is revised to include the missing car information and actually link it to the missing person’s case, but then the VIN, the vehicle identification number, is entered incorrectly. On February 20th, the VIN is corrected. But her plates are never run again.

Quite an investigative failure by any measure.

In the early morning hours of January 14th, not long after Officer Adcock spoke with Don and shortly after Harford and Baltimore County Police had checked the area for Hae’s car, things got more complicated.

Shortly before sunrise, a storm hit Baltimore and brought the city to a halt for days.

* * *

Overnight, the region had frozen over. From Baltimore to Washington, D.C., trees were coming down left and right, covered in heavy, solid ice, and roads had become treacherous, deadly, with over an inch of frozen cover in some places.

The National Weather Service reported, “After a half to three-quarter inch of ice accumulated on trees and wires, 40 mph winds was enough to bring many of them down. Trees fell on cars, houses, utility lines and roads. The Governor declared a state of Emergency in Harford, Baltimore, Carroll, Howard and Montgomery Counties. About a half a million customers were without power and 800 pedestrians were reported injured from falls on ice.”

Emergency rooms were packed with patients who had fallen or suffered a car accident, while newspapers reported hundreds of downed power lines and the struggle of emergency services to respond to storm-related injuries and calls. People were calling it the worst storm in years.

While Governor Parris Glendenning ordered a state of emergency in six Maryland counties, Baltimore was hit worse than southern areas in the storm’s path—temperatures dropped lower in the city than in other parts of the state, down to 18 degrees Fahrenheit, well below the freezing point.

This storm may have impacted the early investigation significantly. Not only were police resources stretched to meet emergency needs, but on January 14th and 15th, Thursday and Friday, school was closed. The following Monday was the Martin Luther King holiday, and school was also closed. This meant that Hae’s classmates and friends, who may have ordinarily been a bit more concerned about her not appearing at school for those three days, were essentially enjoying their time off because of the weather.

This, remember, was a time before every teenager had a cell phone. Most of their contact was either at school or over landlines, many of which were down because of the weather. The kids Adcock contacted on the evening of the 13th didn’t take much notice of Hae’s failure to show up at home or work that day because they knew that Hae was deeply in love with her new boyfriend and also had been having trouble at home; she could easily be weathering the actual and familial storm with him. And it also was common for the group of friends to get calls from parents, or other friends, searching for one of them. They figured Hae’s family was doing the same. So it wasn’t until they returned to school after the five-day break the following Tuesday that they realized Hae was still missing.

Still, many of them assumed Hae was with Don, and one of them, Debbie Warren, was so sure she was with him that she made it her business to find out. Debbie, also a Magnet Program student, set up a fake e-mail account to reach out to Don. She had met him once when she went to the movies with him, Hae, and Aisha. But for this covert operation, she wanted to fish for information about Hae without revealing her identity, believing “he was hiding her.”

After communicating a couple of times over e-mail she fessed up to her identity and they agreed to speak over the phone. That conversation, much to the surprise of police at a later interview, lasted seven hours. They spoke primarily about Hae, and over the course of those hours, her concern that Don had something to do with her disappearance diminished. He seemed genuinely upset and worried about Hae, mentioned that perhaps Adnan had something to do with her being missing, and by the time their conversation was over Debbie felt that she “knew him.” She crossed him off her suspect list.

It wasn’t until the first week after Hae’s disappearance that her friends and classmates began to worry in earnest about her. Aisha Pittman, her best friend, kept the Magnet Program kids apprised of the situation

According to students and friends of Adnan and Hae, some of whom would go on to become witnesses, there was nothing unusual in Adnan’s behavior after Hae’s disappearance. These were the last few months of senior year, and many of these top students had already completed the credits needed to graduate. Many were taking part-time classes, working elsewhere, or just not showing up as frequently.

After it became clear that Hae hadn’t just taken off for a few days, and when the media began reporting her disappearance, Adnan started to worry. He had no relationship with Hae’s family, they were opposed to their relationship after all, and couldn’t call her house. But Hae’s girlfriends were calling to check in with the family, and often in class there would be discussions during which Adnan was now becoming visibly upset and concerned. Aisha would also page Hae every so often, with no response.

At school the kids started to think that perhaps Hae, upset with her mother, had taken off for California to live with her stepfather. The California rumors further muddied the waters for Hae’s classmates and friends.

In the report of an interview with police on March 26th, 1999, Debbie is asked who started the California rumors. She responds, unsure, “Um, I don’t know that for sure, probably me and Ayesha [sic] cause we were the only ones who knew um, that she had family up there that she could possibly been living with, um, some people had asked and you know just about every day someone would ask us, and you know, where we thought she was.”

But a January 27th police interview makes it clear that Aisha wasn’t the root of the rumor.

The report reads, “Hae told Aisha that she had problems with her mom, but it was nothing that would make her leave. Hae talked about California, but she never talked about going there.”

Aisha’s remarks are isolated, in an otherwise extremely brief report, and seem to indicate that she was asked specifically by the police about the possibility that Hae could have gone to California, meaning this was a theory they were exploring, perhaps because Don had mentioned something similar to the authorities in an earlier interview.

In a January 22nd interview with a detective, Don, independently and unprompted, stated that although Hae had no plans to go anywhere, she had mentioned living in California in the past and said she’d like to live there again one day.

Could it be that Debbie and Don’s seven-hour conversation took place before January 22nd, and in that conversation Debbie was the one who suggested Hae may have gone to California? Or was it the other way around? Was Don the original source of the rumor?

It’s doubtful that Debbie would go to such lengths to investigate whether Hae was with Don if she thought California was a possibility. And the first time any mention of Hae’s interest in California appears in any of the documents is Don’s January 22nd interview. It seems, then, that the root of the rumor that Hae might be in California was Don himself, and the rumor spread with the help of the police, who asked others about it, and Debbie, who began mentioning it at school after their marathon chat. It is entirely possible that Don offered this information because Hae had indeed mentioned it to him. But it seems unlikely to me that Hae, who was planning and had paid for a trip to France with her class, according to her French teacher, who was about to graduate from high school, who never mentioned it in her diary, and who was newly in love, would consider just taking off to California. But the idea that she might have left gave her friends, who were confused and worried about her disappearance, something to hold on to. The trail of this story, however, leads back to Don, and the police weren’t the only place he planted this seed.

Enter the intrepid investigatory services of the Enehey Group.

* * *

“The Enehey Group offers its clients services unparalleled in Investigative Research today. Combining a personal approach with the latest information gathering technology and techniques, we strive to provide our services while maintaining complete confidentiality at all times.”

An Enehey Group’s investigative report about Hae’s disappearance submitted to the Baltimore City Police begins with a list of a mind-bogglingly diverse array of services provided by the agency:

Business investigations, missing persons investigations, computer fraud investigations, industrial counterespionage, translations and interpreting, software design, market design, genealogical investigations, historical investigations, compiling psychological and behavioral profiles, consulting on educational issues for emotionally challenged and disadvantage youth, and Pro Bono cases for law enforcement

Notwithstanding consultants, in all meaningful respects for Adnan’s case, the Enehey Group seems to be comprised of exactly one person—Mandy Johnson.

Ms. Johnson’s portfolio has since expanded even further. She is now also a self-published novelist focusing on espionage, terrorism, and the Middle East.

In January 1999, Tae Su Kim, a Baltimore-area Korean-American business owner, brought in the Enehey Group (Johnson was apparently a family friend) to investigate his missing niece.

The five-page report on Hae begins with basic information. It notes that the missing person’s file is with the Baltimore County Police Department, assigned to one Detective Sgt. Joe O’Shea, who took over the case from Officer Adcock. Mandy Johnson, the report notes, has a good relationship with O’Shea; she is in contact with him daily, and she has been sharing her investigative findings with him.

The findings are limited, but interesting. Hae’s family has provided full access to Hae’s belongings, including her diary and computer. Hae’s room appears to have been searched, a routine investigatory procedure, since the report notes that Hae has “left behind her Korean passport and diary.”

Johnson tracks down Hae’s e-mail accounts and her AOL username, and indicates that she was known to spend time on Asian chat rooms.

While the report notes that Hae’s profile has last been checked on January 16, three days after Hae disappeared, it makes no mention of who may have checked the account or who knew of Hae’s Asian chat room activity. The interests and likes Hae lists in her online profile show that they’ve been entered after she began dating Don: “Looking in his blue gray eyes, fast cars like his Camaro, driving to BelAir, selling glasses and her beauty, spending as much time as possible in the lab. Occupation: Part-time sales, Full-time Girlfriend.”

Johnson notes that Hae ends her profile with, “I love you and miss you Donnie.”

Johnson was astute enough to profile Hae’s ex-boyfriend and interview her current boyfriend. But her assessment of Adnan relies on Hae’s diary and perhaps her talks with others, though that’s unclear. She never meets with or speaks to Adnan directly. How she comes to the conclusion that Adnan is “known to be possessive and domineering but not necessarily violent” isn’t explained, but it portends the role she will ultimately play in his fate.

The treatment of Don, whom Mandy interviewed, is entirely benign. Calling him mature and articulate, she spends no time on his background or ethnicity, as she had with Adnan, or even the kind of relationship he had with Hae. Instead, the short write-up of Johnson’s interview with Don focuses on his knowledge of where Hae may have gone. Again California comes up, and this time he also mentions a friend of Hae’s, which doesn’t appear anywhere else in the record, saying she might be at this friend’s home. When asked how Hae might travel to California, Don says that she might park at the “satellite parking facility” of the local airport, BWI, and fly from there. Either that, or drive all the way to California.

We don’t have a precise date for this report, or for when Johnson spoke to Don, but we can deduce that it was after Detective O’Shea spoke to him on January 25th and before the first week of February, since the report notes that Johnson will notify long-distance truck drivers at the Port of Baltimore in the first week of February so missing person posters can be posted at rest stops in the area. The detectives will also meet with the family during the first week of February, and then the media will be alerted.

Other undertakings that the report indicates are completed or planned: various police jurisdictions have been alerted, airline reservations checked, Asian chat lines to be randomly monitored, Hae’s diary to be analyzed, and Korean community members and religious organizations notified.

I have to note here the oddity of an independent investigator, who is not even a licensed private investigator or a former law enforcement officer, becoming so deeply involved in a law enforcement matter. Still, it does seem for all intents and purposes that Johnson was working as a representative for the family to coordinate many aspects of the missing person’s investigation. In fact, she may have been doing more than the police themselves in some regard. All very commendable—with one significant exception.

A memo written months later indicates that this involvement may have ultimately derailed the investigation, something we won’t discover until fifteen years later.

* * *

On January 22, about a week after Hae disappeared, Detective O’Shea gives Don a call. The report taken of this conversation, which is not written up until February 11, is much more extensive than the report taken by Officer Adcock a week prior.

This time, Don tells the police that Hae had spent the evening of the 12th with him. Don’s parents are divorced and he lives with his father, which is where Hae must have been visiting him. Hae returned to her home late at night and had spoken with him on the phone until about 3:00 a.m. He says Hae was scheduled to work on the 13th from six to ten o’clock p.m. and that she was going to call him afterward, apparently to meet up. This is the first time Don’s own whereabouts on the 13th are mentioned. He says that he was “lent out,” that he filled in for someone else at a store he doesn’t usually work at, the Hunt Valley LensCrafters.

He tells O’Shea that he worked there from about 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. and arrived home around seven o’clock, at which point his father told him to call the Owings Mills store. When Don called, he was told that Hae had not shown up for work. His colleagues must have told him the police were looking for Hae, and yet Adcock wasn’t able to get in touch with Don until 1:30 a.m. that night. Don didn’t attempt to call Hae’s family, or page Hae, or reach out to the police himself.

The police never actually visit the Hunt Valley store, or ask for Don’s timesheets or pay stubs to verify that he was working there on that day. Instead, they verify Don’s whereabouts from the manager at the Owings Mills store, a woman named Cathy Michel, who met with O’Shea on February 1st. The report from that day is short, but precise.

So precise, in fact, that it seems Michel must have been reading off of Don’s timecard from January 13 because she cites the exact times he arrived and left work. That is the extent of the police verification of Don’s alibi. After a February 4th meeting, they never call or visit him again.

It is not until months later that anyone attempts to actually get a copy of Don’s employment records for that day, but the document produced by LensCrafters turns out to raise more questions than it answers.

* * *

Over the next few days O’Shea attempts to get a handle on what Hae’s plans and activities were for the afternoon she disappeared. He first interviews Adnan on January 25th. Adnan tells him that he last saw Hae on the 13th at school, during school hours, after which he went to track. Adnan tells him he didn’t see Hae leave school, that school was closed for the next two days, and he had no idea where she was. Adnan explains that while they had been in a relationship they had kept it private because of their families, and that they had broken up but remained good friends. The detective has a few calls with Adnan and schedules a meeting with him, a meeting that was to take place without the presence of his parents because Adnan felt uncomfortable discussing the relationship in front of them. The meeting is set for February 10th, but never takes place because of an unexpected development.

O’Shea then interviews both Aisha and Debbie over the next couple of days, January 27th and 28th, trying to determine Hae’s last known movements. Aisha reports she last saw Hae on the 13th at 2:15, when school was dismissed, and that she was in good spirits. Debbie says she last saw Hae at around 3:00 p.m., near the gym, and that Hae told her she was going to see Don at the mall. But neither Aisha nor Debbie actually saw her leave the school.

It isn’t until February 1st that a flurry of activity seems to indicate that foul play is suspected and the police are looking at possible suspects.

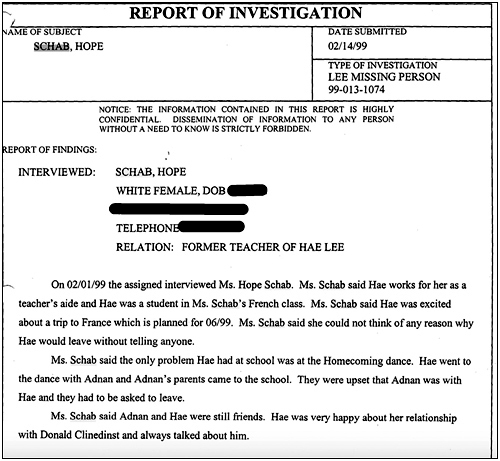

O’Shea takes a trip to Woodlawn High to meet and interview a number of people, including the French teacher, Hope Schab, track coach Gerald Russell, and athletic trainer and teacher Inez Butler. His questions for Schab are about Adnan and Hae’s relationship. Schab mentions that the only trouble she knew of between Adnan and Hae happened at the homecoming dance, but that they were still friends. Russell is asked whether Adnan attended track practice on the 13th and he’s unsure—he doesn’t take attendance and recalls that it was Ramadan, and during Ramadan athletes are required to attend practice but don’t have to run.

Butler’s statement seems to contradict what others have said. According to her, she last spoke to Hae on the 13th and Hae was upset, having problems at home, and wanted to contact her father in California. Butler also recounts that Hae told her she would not be at the wrestling match that evening, the first time a wrestling match is mentioned.

The wrestling match becomes more of a focus, and part of the case narrative, with a later discovery of a note Hae has written. But ultimately it will turn out that, like so many other witnesses, Butler is not remembering the right day.

February 1 is the same day O’Shea checks in with Cathy Michel at LensCrafters in Owings Mill and she confirms Don’s alibi, and then the detective calls Adnan again. This time, however, he raises a question that he had not asked previously.

Did Adnan ask Hae for a ride after school that day? According to Adcock’s report on the 13th Adnan told the officer that he was going to be getting a ride from her, but he ran late and she got tired of waiting and must have left. Adnan denies telling Adcock this, saying he had his own car and didn’t need a ride that day. It is odd that O’Shea didn’t bring this issue up with Adnan previously. This raises the question of whether that prior report did in fact contain that information initially, or it was added later. There is also the possibility that Adnan, who sometimes got a ride with Hae to the far side of the school for track practice, didn’t really consider that “a ride.” It could be simple miscommunication. Perhaps he assumed the police meant an off-campus ride, which he normally didn’t ask for because he usually had his car and because he knew Hae had to pick up her cousin. Did he forget that he asked for a ride? Then there is the possibility that Adnan did ask for a ride, but later, worried about the implication, he lied to the police about it.

The thing was this: Adnan did have his own car, but he didn’t have it with him during much of the day on January 13. He had loaned it to Jay Wilds, his friend Stephanie’s boyfriend and his go-to guy for weed, and hadn’t gotten it back until after track practice. Whether or not he had asked Hae for a ride after school, while the car was with Jay, this issue will come back to haunt Adnan.

On their February 1, 1999, school visit, the police didn’t just question some of the staff; they deputized one in particular to find out intimate details about Adnan and Hae’s relationship.

Hope Schab, the twenty-seven-year-old French teacher, was not much older than her students. She considered Hae, who worked as a student assistant in her French class, to be a friend. So when the police asked Schab to question students about things like where Adnan and Hae would meet for sex, she didn’t hesitate. She made a list of questions, and word eventually got back to Adnan that his sex life was the subject of Schab’s queries. But he didn’t just hear it, he saw the actual list of questions in Debbie’s school planner when be borrowed it, and, according to Debbie, he returned the planner without the list, insinuating that he took them. Adnan doesn’t remember this incident, but he thinks it could be possible because he would have been shocked to have seen it, though on the other hand he doesn’t give much stock to Debbie’s statements

At this point Adnan had been twice contacted by the police, the night that Hae disappeared by Officer Adcock, and then on February 1st by Detective O’Shea. The sudden whispers about him at school were unsettling; he was already deeply concerned by Hae’s disappearance, and now a teacher was digging around about his sex life. The last thing he needed was word to get back to his parents, who had no idea that he and Hae had been sexually involved. Not even his Muslim friends knew that, at least no one other than his best friend, my brother, Saad. But now a teacher, of all people, was asking his friends, including those who went to the same mosque and whose mothers knew his mother, about where he’d been having sex with Hae.

Community gossip moved at lightning speed. The prospect of his mother finding out that he’d been having sex was terrifying, as it would be to any level-headed seventeen-year-old Pakistani kid.

According to Schab, Adnan approached her and asked her, rather politely, to stop prying into his sex life. He told her he “would appreciate it” if she stopped asking questions around the school because it could potentially cause problems with his parents. He had no idea that the police had asked her to ask those questions, but assumed that she was playing sleuth herself.

It’s both interesting and telling that the official police report doesn’t mention the role Schab was asked to play. But both Schab and Debbie Warren will testify to this less than a year later.

On February 2nd the police contact authorities in Hayward, California, and ask them to visit Hae’s mother’s ex-boyfriend or fiancé (reports are conflicting about the relationship) who Butler was presumably referring to as Hae’s father. They check in with him, and do a sweep of the area for her car, but find nothing.

On February 3rd, the detective checks to see if Adnan is listed in MILES, the Maryland Interagency Law Enforcement System, an online database. His records are clear. O’Shea does not check on anyone else.

On February 4th, the Baltimore Sun puts out a request for information on Hae:

Hae Min Lee, who lived with family members was last seen about 3 p.m. January 13[th] at Woodlawn Senior High School, where she was a student. After school she was supposed to pick up her 6-year-old niece and go to work, police said, but she did not do either.

It’s fair to assume the newspaper was given this information by the police, so at that point their theory was certainly that (1) Hae was at school until 3:00 p.m. and (2) she had plans to work that night, not attend a wrestling match.

Once the police take the case public, they begin actively organizing searches for Hae and her car. On February 6th, police search the areas around Woodlawn High with dogs, and follow the banks of the western part of Dead Run Stream into Leakin Park.

Two days later, on February 8th, Adnan calls Detective O’Shea, which we know from his cell phone records, but there are no notes of that conversation anywhere. It is possible the phone call was regarding their meeting scheduled for the 10th. Also on the 8th, nearly a month after Hae’s disappearance, O’Shea retrieves Hae’s computer from her family, and the Computer Crimes Unit issues a subpoena to America Online for records connected to Hae’s e-mail accounts.

Clearly the police are now looking for communications from or to Hae leading up to January 13th. But this line of inquiry will come to a screeching halt, and frustratingly be completely forgotten, because on February 9, 1999, the body of a young woman is discovered in Leakin Park.

Adnan:

After January 13, the next two days were snow days, and then it was the weekend. We talked about it in school that first week, and there was a general assumption Hae was either staying with her boyfriend, or perhaps she went to California. She had spent her sophomore year in California, and we all knew that her father and other family members/friends lived there. As far as her missing school; well, that really was not an issue for most of us who were in the Magnet Program. We had accumulated enough credits to graduate by the beginning of our senior year. Some of us would take half-days, or even skip the whole day together. We may have had jobs or internships to attend, or we may have just gone somewhere and hung out.

Going into the second week was when we all became more concerned because no one had heard from her. We all knew that Hae’s mother had called the police on the first day. And the officer had contacted several of us. Any notion that something was really wrong was belied by the knowledge that Hae was someone who always had it together, and surely she was all right. I remember thinking, “Man, Hae’s gonna be in so much trouble with her Mom when she gets home.”

By the third week, that worry had turned to fear. No one knew what to think. Krista and Aisha would call Hae’s house every day and speak to her family, to see if there was any news. The rest of us would talk to Krista and Aisha to find out if there was anything they had learned. But there was never anything for them to pass on to us.