The burden of proof is on the proponent

and the oath is incumbent on the one who denies

Ahmed ibn al-Husayn al-Bayhaqi, Book of the Great Sunnah

After the police picked up Adnan, he was put in the back of a Baltimore City Police cruiser, driven to the police station, and his car was impounded and towed away. He recalls one of the officers in the car teasing him, telling him he was so pretty he was going to get fucked frequently where he was headed. He was talking smack and Adnan knew it, but he didn’t understand why the officer was being so mean to him. The female officer driving the car was polite though, telling him that he was being taken for questioning, a small kindness he still remembers.

He was taken into an interrogation room and cuffed to the wall, then read his rights. He agreed to answer the detectives’ questions without an attorney, thinking this would soon be over.

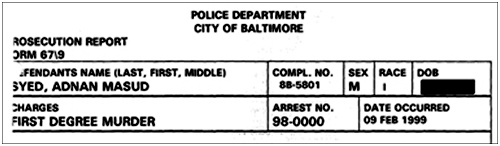

Prosecution report of charges of first degree murder against Adnan Syed

Detectives Ritz and MacGillivary tried a variety of tactics to get Adnan to talk, from showing empathy (“Hey, I know how you feel, my ex-wife makes me mad too”), to getting tough (“We know what you did and we’re going to prove it by finding your boots, process your car, finding your red gloves”). Then they told him that they knew he and Jay did it.

Adnan responded that he had no idea what they were talking about. Red gloves? He and Jay did it? He was completely baffled. As he sat there cuffed inside the homicide unit he was thinking about his school work. It was Sunday morning, and he had an annotated bibliography due the next day. How long was this all going to take, he wondered.

The detectives left the room after questioning him for a bit, then returned with the Metro Crime Stoppers flyer, sliding it across the table toward him. Adnan leaned forward, looking at it, then looked at them. He still didn’t understand what they were implying. They told him to look at the flyer, look at Hae, take some time, and then tell them what happened. They then left him to be alone with Hae’s picture.

After a bit they returned and placed a document on top of the flyer. It was the charging document, stating that Adnan Syed was arrested for the first-degree, premeditated murder of Hae Min Lee.

This was the point at which Adnan, thinking back to the years of Matlock he had watched, asked for a lawyer. What he didn’t know was that even before his interrogation was over, a lawyer was already at the police station, trying to stop the questioning and see his juvenile client.

Attorney Doug Colbert, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Law, had been retained within an hour of Adnan’s arrest. He was contacted by Bilal Ahmed, who had been called by Tanveer as soon as Adnan was taken away. For many years Colbert was the senior trial attorney in the Criminal Defense Division of the NYC Legal Aid Society and had spent much of his career writing and speaking on defendant rights. Before joining the Legal Aid Society, Colbert taught the criminal justice clinic at Hofstra Law, where one of his students was an eager and sharp young man by the name of Chris Flohr. Upon graduating, Flohr also joined the Legal Aid Society, where he litigated trials for every kind of felony. But Flohr eventually left New York and moved to Baltimore in 1998, and when Adnan was arrested he was the legal director of a program focusing on bail reform in Baltimore City. Colbert tapped him to help assist with Adnan’s case.

Adnan had waived his rights to an attorney at 7:55 a.m., but by 7:10 a.m. the police had already known Adnan was represented and had been advised to stop the interrogation. And yet they didn’t. They continued their questioning of a minor, preventing his attorney from being present, refusing to let Adnan’s parents see him, and also refusing, despite the attorney’s request, to record the interrogation.

Finally, after attempting all morning to gain access to his client, attorney Doug Colbert faxed a frustrated letter to Detective Marvin Sydnor at 1:34 p.m.

Dear Detective Sydnor,

I represent 17 year-old Mr. Adnan Syed, whom I understand you have had in police custody concerning a pending homicide investigation since approximately 6 a.m. this morning. I write to reiterate my numerous requests that I have made this morning to permit me to speak to my client immediately and that you cease any questioning in my absence. […]

Despite my repeated requests, Detective Sydnor refused to tell Mr. Syed that his attorneys were present and declined to cease questioning. I also asked Detective Sydnor to videotape the interview and questioning of Mr. Syed, but the Detective refused by saying that I ‘wouldn’t want to tell you how to defend someone in court.’ Finally I asked Detective Sydnor to permit Mr. Syed’s mother and father to see their son immediately. Detective Sydnor again declined my request. […]

We repeat our request to see our client, Mr. Syed, immediately upon receipt of this letter.

The letter and their repeated attempts failed. Having held Adnan for six hours of interrogation, the police did not record or videotape any of it and did not inform Adnan about his attorneys until it was over. Only a few lines of notes were produced, notes pertaining to the reading of Miranda rights and Adnan’s waiver of his right to having an attorney present during questioning.

According to Adnan, after he had asked for an attorney, he didn’t speak to the police again and the interview wrapped up. But one of the last things he remembers Ritz saying to him, after he asked when he could go home because he had school work to do, was, “Adnan, you’re not going home.”

* * *

After a long booking process Adnan was given one five-minute phone call. He spoke to Tanveer, telling him he had been charged with Hae’s murder, and then he asked for his mom.

Adnan:

Subsequent to my interrogation at the police station, I was transported to the Central Booking Intake Facility. I was fingerprinted, photographed, and also given a basic health screening. I was next brought before a court commissioner, who informed me that because I was charged with First-Degree murder, I would be placed on a “No-bail” status. He further explained that because of this status, I would immediately be remanded into the custody of the Baltimore City Detention Center until trial. I actually remember the exact words he spoke; he was reading them off a piece of paper. He ended up with, “until trial, or such time as the Court orders your release.”

This entire process lasted several hours, as between each step there was a period of time which I spent waiting in various holding cells. Once the booking process was complete, I was permitted to make one phone call. I was directed to a chair that was adjacent to a desk with a phone on it, and informed that I had five minutes. I dialed the number for my home, and after a few rings, my older brother answered. Initially, I couldn’t respond to his “Hello? Hello?” because I had no idea what to say. Eventually, I said to him, “Tanveer, hey, it’s me.” I told him that I had been taken to the police station, and that they had charged me with Hae’s murder. I didn’t know at the time, but by then I believe there was news coverage, and my family was already aware. I explained to him that I was in the Booking Facility, and that I was being transferred to the City Detention Center. He asked how I was doing, and if I was alright? Hearing the worry and fear in his voice, I did my best to assure him that I was fine, and surely this whole thing must be a huge mistake, and that it would probably be straightened out soon.

By then, the officer informed me I had only one minute left. I asked my brother, “Is Mom there?” and he passed the phone to her. I heard her say, very softly, “Adnan…” and immediately I could tell that she had been crying. It was the first time throughout the whole ordeal that I felt my resolve begin to crack. I struggled to keep my voice steady, as I conveyed to her that I was alright, and that this would all end soon. I asked her how Yusuf was doing, and she told me that he had been very upset, but that he had gone to sleep. I only had a few seconds left, and I reassured her once again that I was well, and that she shouldn’t worry. I promised I would call home again as soon as I could. I was relieved to hear a measure of calmness in her voice as we said our good-byes.

I was next taken to a shower area, and strip-searched. There was a faucet which dispensed anti-bacterial soap, and I was instructed to wash my entire body with it. An officer stood there and watched to make sure I complied with that order. I was handed a green jumpsuit, and given a brown bag which contained breakfast. In it was an 8 oz. carton of milk, two boiled-eggs, four slices of bread, and an apple. After I was finished eating, I was handcuffed and escorted to the Detention Center, which was linked to the Booking Facility by a series of long corridors.

I was taken to the juvenile wing, and from that point on, it was just a matter of waiting. I would spend the next several months reading a lot of novels, playing basketball, and exercising. I learned a lot of table-top games, such as chess, Scrabble, various card games, etc. We’d have an opportunity to make phone calls once a day or so, during our recreation time. There was a television in the rec. hall area, and we could also take showers during that time. Sporadically, there were disturbances, fights, etc., and we would be placed on lock-down. We would be confined to our cells, and this could last a day, several days, or even weeks, depending on the nature of the disturbance. We were also allowed to submit requests to the law library. I would order legal materials, trying to understand the trial process. It was very difficult; I had no idea what to request as I had no clear understanding of what I was going through, legally.

* * *

Adnan tried to maintain a calm demeanor with his family. But when he called Bilal he wasn’t able to control his emotions.

At a grand jury proceeding on March 22, 1999, Bilal testified about the call saying Adnan was “hysterical,” and “he was crying a lot so—and it was hard for me to understand from his conversation was that he was—I mean, he was devastated. He’s like denying it. I didn’t do it.”

It’s not surprising that Adnan called Bilal and let his emotions loose. Bilal was his mentor.

Adnan now describes Bilal as a real-life Fagin from Oliver Twist: encouraging kids’ corruption while protecting his own reputation, feigning self-righteousness to cover misdeeds. Adnan and the other kids knew things about Bilal that the rest of us didn’t. But upon his arrest, Adnan knew Bilal was the guy who could help his family cope.

And he did. It was Bilal who recommended Colbert to the family the morning Adnan was arrested, and now he was organizing meetings at the mosque to raise money and get ready for the bail hearing, which was what the attorneys told him to do.

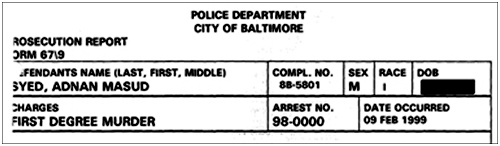

The first bail hearing was set for March 1, 1999, when Adnan appeared via video conference in the Baltimore City District Court. His attorneys requested that bail be set at $25,000, but it was denied thanks to an error on Adnan’s charging documents: his birth date.

Adnan’s birthday is May 21, 1981. But his arrest warrant, the document before the judge, incorrectly noted his date of birth as 1980. In fact, this mistake remains on his criminal record to this day.

In 1999 the death penalty still existed in the State of Maryland, but not for minor defendants. However, this judge, seeing the arrest warrant, incorrectly assumed Adnan was an adult and twice referred to the case as a capital case, thus not eligible for bail.

On March 16, Colbert and Flohr filed a Writ of Habeas Corpus with the circuit court, a legal mechanism by which to challenge the imprisonment of a defendant. A hearing on the writ was held shortly thereafter, on March 31.

In the week before the bail hearing, the community scrambled to both raise funds and collect character letters of support for Adnan from people with whom he had grown up, worshipped, and gone to school. About one hundred such letters were submitted to the court, and buses were arranged from the mosque to the court early on the day of the hearing. Nearly a hundred people filed into the courtroom and hallways outside the courthouse.

“I’d never seen anything like it,” says Doug Colbert. A number of community members, all doctors, offered their homes as bail collateral.

They expected Adnan, a kid with no record, well-loved and supported by a community spanning professionals, religious leaders, and peers, would be viewed by the judge favorably. And he might have, if prosecutor Vicki Wash hadn’t made an argument that left us all stunned.

Before a room full of Muslim citizens she said to the court, “Your Honor, the fact that the defendant has strong support from the community, that is what makes him unique in this case. He is unique because he has limitless resources; he has the resources of this entire community here. Investigation reveals that he can tag resources from Pakistan as well. It’s our position, Your Honor, that if you issue bail, then you are issuing him a passport under these circumstances to flee the country. [… T]here is a pattern in the United States of America where young Pakistani males have been jilted, have committed murder, and have fled to Pakistan, and we have been unable to extradite them back. […] We have information from our investigation that the defendant has an uncle in Pakistan, and he has indicated that he can make people disappear.”

That was the first time that the community got an inkling of what was really going on: the police went after Adnan because he was Muslim and Pakistani. If they, upstanding citizens, could be indicted by this prosecutor in one broad sweep, then it was clear that the core of the police’s theory hinged on Adnan’s religion and ethnicity. No one expected—least of all Adnan’s attorneys—to hear such an argument. But Wash didn’t make that argument up on the fly. She had prepared for it, having spoken with a legal advisor at the Department of Justice (DOJ) and, just a few days prior, having honed in on mosque members and a friend of Adnan’s to ask questions about Islam. Defense notes indicate that three days prior, “Detectives Ritz and MacGillivary along with Vicki Wash made a 7:30pm visit to the residence of a Hindu friend of Adnan’s and asked questions about Islam.”

Many points affirm that Adnan was targeted because of his religion and ethnicity. This is one of them. There is no other explanation for a prosecutor, who could easily argue against bail based on the heinous nature of the crime, based on premeditation, or based on witness statements, to research and prepare an argument connected with his ethnic background, which for them was basically interchangeable with his religious affiliation. This, of course, doesn’t even address the fact that Adnan isn’t, and never has been, a Pakistani citizen. He is an American citizen, born and raised in the United States.

The following day, bail was denied.

Wash’s arguments inflamed Adnan’s attorneys, who reached out to the DOJ legal counsel she had consulted, and wrote a letter of complaint to the State’s Attorney.

In arguing that Mr. Syed presents a risk of flight, Assistant State Attorney Vicki Wash relied upon improper and erroneous assertions concerning Mr. Syed’s nationality, ethnicity, ancestry, and religion. Ms. Wash also referred to the national origin and religion of Mr. Syed’s parents and made a similar references to the Baltimore community that supports Mr. Syed’s pretrial release. [… I]n my opinion, Ms. Wash’s presentation was wholly outside the boundaries of proper argument.

Colbert had also contacted the legal advisor from the State Department, Harry Marshall, whom Wash had cited in making the argument that there was a “pattern” of Pakistani men killing their partners and then fleeing the country. Marshall reached out to Wash to correct her, and she subsequently wrote a letter of apology to the judge, stating that there was no such pattern. In fact, there was exactly one case in Chicago in which a Pakistani man was charged with murder. The victim was known to the defendant and an element of “treachery/deceit” was involved. Even Wash’s apology was deeply insulting. In essence she explained to the judge that because, in a murder case in another state a Pakistani defendant had used treachery and deceit, she assumed Adnan would as well. This is textbook biased or bigoted behavior.

In any case, Wash’s correction and apology didn’t matter anymore. Adnan wasn’t getting bail, and no matter how many times the issue was raised in the future, it was denied. Ritz was right, Adnan wasn’t going home.

* * *

After the bail kerfuffle Colbert and Flohr realized that this case was going to require some major fire power, an aggressive attorney with much greater experience than they had. They advised Bilal Ahmed, who was acting as a liaison between the community, family, and attorneys, and then began searching for another attorney. One came to mind immediately, a legend in the criminal defense world—Cristina Gutierrez.

Gutierrez was already involved peripherally in the case. She had been hired to represent two witnesses from the community who were called to testify at the grand jury proceedings: my brother Saad Chaudry and Bilal Ahmed.

My parents were terrified, like many parents of Adnan’s friends. After hearing Wash’s arguments at the bail hearing, they were convinced the State was going to try to rope in as many of their young boys as possible.

“Don’t go, just don’t go,” my mother said when Saad’s subpoena came.

“He can’t do that, it’s against the law. He has to go, he has to have a lawyer, and then he’ll be just fine,” I said, trying to reassure both my parents and myself.

Both Saad and Bilal testified between March 22 and April 7 but did so only after Gutierrez had attempted to quash the State’s subpoena calling them—a routine move by defense counsel. When that didn’t fly, she advised them that while they would have to testify, they should, between every question, reaffirm their privileges and confer with Gutierrez before answering. It resulted in testimony that, though lacking in substance, was high in drama and difficult to follow. It wouldn’t be the last time Gutierrez left a jury with a bad taste in their mouth.

* * *

Bilal Ahmed and Saad were both asked whether Adnan had confided in them about the murder.

The prosecutor asked Bilal, “Did you ever have a conversation with Adnan Syed prior to January 13th about murdering Hay [sic] Min Lee, about his intentions to murder Hay Min Lee?”

Bilal answered, “No, I didn’t.”

Likewise, Saad was asked whether Adnan ever denied involvement in the crime, and Saad responded that Adnan indicated he had no idea who did it. The prosecutor challenged him, “So you’re saying that his response to your question of I have no idea who did this is the same as saying he denied any involvement in the crime?”

Saad, who recalled being confused, said, “Yes.”

Both not only maintained that Adnan had never indicated that he was in any way involved with Hae’s disappearance or murder, they also testified to how Adnan reacted to the news of her death and his arrest.

“He was crying and he informed me … that she had died … he was upset and crying,” testified Ahmed.

Ahmed’s testimony was much more substantive than Saad’s. He was questioned for days about his role at the mosque, his relationship as a mentor to Adnan, what Islam had to say about dating, sex, and marriage, and repeatedly, Adnan’s relationship with Hae and his involvement, if any, with the murder.

While Ahmed didn’t provide anything that could be used against Adnan, he did mention something very important: on the evening of January 13, 1999, he specifically recalled seeing Adnan at the mosque. In fact, he looked over Adnan’s notes to help him prepare to lead prayers the following day.

Suddenly, Ahmed posed a potential problem for the State—he could derail Jay’s story about where Adnan was the night Hae disappeared. The suspicion of the State extended to Adnan’s Muslim friends, though.

This explains why, shortly thereafter, on April 13, 1999, the Baltimore City Police subpoenaed Bilal’s phone records. They were looking for some way to shut this guy down.

Not all the grand jury testimony was made available to the defense. Other than the detectives, the only witness for the State, at least the only one disclosed, was Jennifer Pusateri. Jay Wilds was not called.

On April 14, 1999, Adnan was indicted for the murder of Hae Min Lee.

Adnan:

We had visits once a week, and that’s what I looked forward to the most. Only two adults were allowed, so my mother would always come accompanied by either my father or older brother. The visiting room contained a u-shaped table, with clear plexiglass separating the inmates from the visitors. It was a non-contact visit, and we had to speak through a mesh grill. In the beginning of our first visit, my parents seemed very tense and upset. As we talked, however, they began to calm down. I told them about the things I had eaten, and about something funny I had read.

As I saw their change in demeanor, I felt relieved. The thing that worried me the most was thinking about how hard this was on my family. How they must have been hurting, and the helplessness they were feeling. I came to understand that they were very concerned about my well-being; scared that perhaps I was experiencing some emotional and/or physical harm. I made a decision at that point, determining that no matter what happened regarding my case, I would do my best to remain positive when it came to my family. I would exercise and stay in good shape, so they would see me healthy when they would visit. And during every phone conversation, I would always try to have something positive to talk about. I realized that if I could not affect anything else, I would try to ensure that my parents had no reason to worry about my physical and mental health, because they would always see me in a good state of mind.

It would require a good deal of effort, though. Some days were harder than others. During one attorney visit, my lawyer handed me an envelope, telling me it had arrived at my parent’s home the previous day. It was an acceptance letter from one of the colleges I had applied to. There was also my 18th birthday, which occurred about two and half months after my arrest. There was our high school commencement day, where I was scheduled to have graduated. And at the end of that summer, there was what would have been the first day of college. Every few weeks, it seemed that a moment would come where I would realize I had planned to be somewhere else.

There was one day in particular. Several weeks after I was arrested, there was the Eid festival. It would normally be a time of joy & celebration in our household, but now it was a moment of incredible sadness. It was particularly difficult for Yusuf, as we would always make it especially fun for him, with presents, candy, cake, etc … I worried a great deal about how all of this was affecting him, as he was so young. My parents would refrain from telling me, but I constantly questioned my older brother about how Yusuf was doing. Finally, one day Tanveer broke down during a phone conversation and admitted to me that Yusuf was no longer attending school. He was being bullied by his classmates to the point where he would come home crying, begging not to be sent back to school the next day … To learn of what my little brother was experiencing brought about an immeasurable amount of sadness. It made the hardships of what I was experiencing pale in comparison, and there was a great deal of frustration as I felt helpless to do anything about it.

* * *

As Adnan waited in jail, his family and mosque friends would often visit him, but he hadn’t heard much from his classmates. He had no idea why or what was going on but thought it best, at the advice of counsel, not to initiate contact; for all he knew, that might make people uncomfortable. In addition, he could only make collect calls, expensive calls, and he didn’t want to burden or pressure people to take them. But he did hear from one student, someone he wasn’t even close friends with.

Asia McClain.

Asia was a beautiful girl who used to date one of Adnan’s friends, Justin Adger. Adnan knew her casually through Justin, but she wasn’t part of the Magnet Program so they weren’t close. Plus, she and Justin had broken up and she was dating someone else now, someone who didn’t go to Woodlawn.

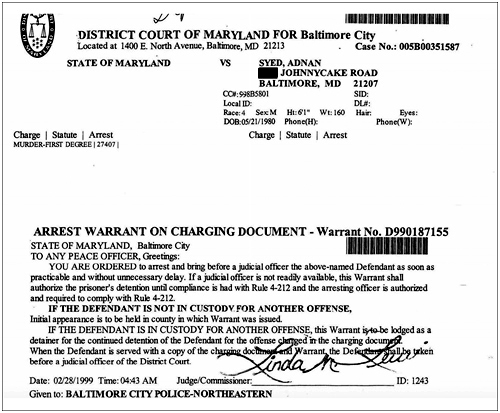

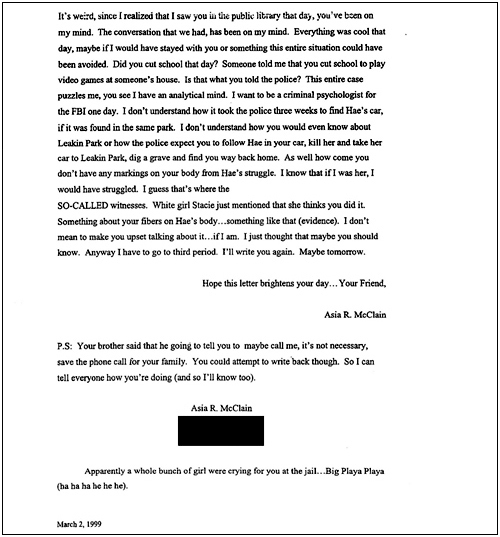

Sometime in the first few weeks of being locked up Adnan received two letters from Asia, back-to-back. The letters are dated March 1 and March 2, right after his arrest, but there is no record of when he actually received them. It might have taken up to a month or more, according to Flohr, for Adnan to receive them since he was moved a few times.

Asia’s first letter describes visiting Adnan’s family on the night he was arrested, and details her recollection of seeing Adnan on the afternoon that Hae disappeared.

The second letter reiterates her having seen him and discusses some of the school gossip about Adnan.

Asia’s letters jogged Adnan’s memory. Until then he had simply recalled that Jay had his car that day and he had hung out at school until track practice at 3:30 p.m. But now he remembered seeing Asia, and the conversation they had had, and later teasing Justin about seeing her new boyfriend with her.

These letters were vital. Adnan thought about contacting Asia but then decided it would be better if his attorney did so—he didn’t want to do anything that could be misconstrued, like talking to an important witness.

At that point they were still trying to choose an attorney.

Cristina Gutierrez came highly recommended by both Colbert and Flohr. After asking around, and then being represented by her at the grand jury, Bilal Ahmed agreed—Gutierrez would be an effective, aggressive, take-no-prisoners advocate.

Gutierrez went to visit Adnan in prison on April 16, and on April 18 she was hired by his parents for the legal fee of $50,000.

* * *

Having overcome a relatively minor 1971 shoplifting conviction that created major issues in her admission to the bar, Cristina Gutierrez was licensed to practice law on October 26, 1982, three years after graduating from law school. By this time she was already a well-known Baltimore activist. In 1973 she had traveled to Cuba and joined the Venceremos Brigade, a group of young American activists who challenged U.S. policy toward Cuba by showing solidarity with Cuban laborers. Her fighting spirit clearly spilled over into her legal work.

A Baltimore Sun article notes that she was considered one of the best attorneys in her office, trying more cases than anyone else and rarely taking a plea for clients. A colleague called her the most tenacious lawyer he’d ever seen and said, “You push her, you better be ready to kill.”

After leaving the Public Defender’s office in 1986, she joined forces with a nationally known criminal defense attorney, Billy Murphy. Together they commandeered the most feared and aggressive criminal defense firm in Baltimore.

Gutierrez litigated fiercely for her clients, getting acquittals in numerous high-profile cases, including a 1991 murder case in which the client had made incriminating remarks to the police. Her tenacity led to a victory before the Supreme Court in a 1990 landmark case, in which she became the first Hispanic American woman of record to argue a case before the highest court in the land. Her victory in this case, Maryland v. Craig, is still cited in evidence textbooks as setting the precedent for a defendant’s right to confront the witnesses against him.

In January 1995 she parted ways with Murphy in a move that left the Baltimore legal community a bit stunned.

A January 17, 1995 Baltimore Sun piece reported that “Flamboyant criminal defense lawyers William H. ‘Billy’ Murphy Jr. and M. Cristina Gutierrez have parted ways after years of sharing controversy and high-profile clients. The long-rumored professional split became official yesterday, when receptionists began answering the phone ‘Murphy and Associates’ at the partners’ Calvert Street office, and Ms. Gutierrez completed the task of moving into the downtown firm of Redmond, Burgin & Cruz, where she will have a limited affiliation. Ms. Gutierrez, a divorced mother of two, called the breakup ‘amicable’ and said that she was hoping to better control her workload and spend more time with her family.”

The split was anything but planned, however, and Gutierrez later admits this to the court in an appeal case for her client John Merzbacher. Explaining why she failed to convey a plea deal to him, Gutierrez states “On January 15, without planning whatsoever, I was forced to move my law office, literally overnight. And that created a great burden on me. Also in January I was in the middle of hearings in front of Judge Ferris, an administrative law judge in Anne Arundel County in the case against Laurie Cook. Those hearings took well over 200 hours and had been started about the second week of December.”

Looking back now, Murphy recalls that shortly after the split Gutierrez’s personality began to change “dramatically.”

“She became really hostile towards people she had known for years,” says Murphy. She alienated colleagues and friends over the next few years, losing many of her allies. Many of them were aware that these changes were probably due to her failing health.

“She was going through evidently very, very serious mental decline as a result of her numerous other illnesses. She was on dialysis, she had kidney problems, I think she had problems with diabetes, so these things evidently changed her mental state to such a degree that her ability to attend to her practice sharply declined … this was not the Cristina of old,” Murphy said in an interview with journalist and attorney Seema Iyer.

In 1999, by the time she was hired to defend Adnan, the effects of her multiple illnesses had long impaired her work in ways that in many cases would not be discovered for a few more years. Unaware of this, the community placed Adnan’s life in her hands.

* * *

In the next two months, both the police and defense conducted a flurry of interviews.

The day after the arrest, and the day of the first bail hearing, my brother Saad and Krista Meyers, both friends of Adnan’s, were interviewed by the BCPD. According to Saad, he was harassed and threatened by the detectives to tell them what he knew about the crime, or face being charged too. Saad wasn’t intimidated, he says; he was on the verge of telling them to “get the fuck out of here.”

Krista was interviewed about Adnan and Hae’s relationship but little was gleaned by the police that could be used against Adnan, except for one thing: “Krista Myers stated that on 13 January 1999, 1st period Photography Adnan had a conversation with Hae Min Lee. Adnan was requesting a ride home from Lee.”

This wasn’t the first time in the investigation that the police heard that Adnan had asked for a ride. In Officer Adcock’s very first interview with Adnan, the day Hae disappeared, Adnan told him he was supposed to get a ride from her but she got tired of waiting and left. But when Adnan was questioned by the police at home in front of his father, he said no, he did not ask for a ride at all.

The ride issue cropped up yet again, though, when the police interviewed Becky Walker, a friend and classmate of both Hae and Adnan. Becky was interviewed by the State’s Attorney and detectives in April, when she also recalls that she had heard, but not witnessed, that Adnan had asked Hae for a ride after school to his car, but then at the end of the day she told him she wouldn’t be able to take him.

Police notes from Becky’s April 9, 1999, interview state, “Heard about it at lunch. Hae said she could—there would be no problem. At end of school—I saw them. She said ‘Oh no, I can’t take you, I have something else to do.’ She didn’t say what else.”

The problem was that Adnan completely denied the ride. But then, if a ride was part of his plan to kill Hae, it would be utterly nonsensical of him to ask for it repeatedly in front of others.

The notes from the same April 9 interview say that Becky also said that “defendant always in victim’s car. Almost every day he would go to back (parking lot) and she would drive him around front so he could go to track practice.”

Earlier, on March 26, Debbie had said to the police, “Um he would either be in the car after school when she went to bring the car around the front and go with her to bring the car around front. Sometimes he would go and he wouldn’t come back um, that’s only when er, after school at that time he would be in the car with her.”

Whether or not he asked for a ride, at the end of the day, if Becky is to be believed, Hae told him no. And Aisha also told Krista Meyers that later in the day Hae had told Adnan that something came up, and she couldn’t give him the ride anyway.

If a ride was part of Adnan’s premeditated plan to murder Hae, Jay Wilds and Jenn Pusateri certainly didn’t know about it during their initial interviews. Jay point-blank told the police “no” when asked if Adnan mentioned how he got in Hae’s car, and Jenn likewise said in her February 27 interview that Jay “didn’t know where her car was or how Adnar [sic] got to Best Buy or how um he got into Hae’s car, if he did it in Hae’s car or whether he did it in Hae’s car.”

Between the time Adnan was arrested and April 29, detectives conducted nearly fifty interviews with Adnan’s friends and teachers at Woodlawn, friends outside of school (mosque friends and Nisha Tanna), and friends of Jay Wilds. They visited the school repeatedly, and assured the students and staff that they had the right guy, that there was solid evidence against Adnan.

From Becky Walker’s journal after Adnan was arrested

Asia mentions this in her second letter when she recalls Hope Schab interrupting a student conversation to say, “Don’t you think the police have considered everything, they wouldn’t just lock him up unless they had ‘REAL’ evidence.”

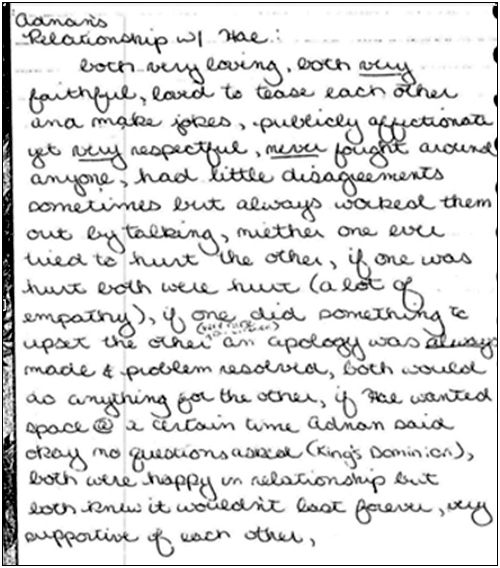

The substance of nearly all the police interviews was to establish what kind of relationship Adnan and Hae had, what challenges with family and religion they faced, how he reacted when they broke up, and how he reacted when she was found dead.

It was a hunt for any behavior that was suspicious, any inkling that would confirm their foregone conclusion: that he was an obsessed, heartbroken, angry young Muslim man who couldn’t take the end of the romance lightly, who thought he had some Islamic duty to kill Hae, and whose community would accept his behavior.

Woodlawn friends and teachers weren’t able to offer much more than banalities, many of them in fact affirming that Adnan and Hae had a good relationship, that there was never any violence between them, that even after breaking up they were friends. But they did all report that their relationship suffered because of family and his faith.

Debbie Warren was the only one who reported that Adnan was possessive, but initially her suspicion was clearly on Don, as evidenced by her belief that he had perhaps “hidden” Hae and her surreptitious e-mail message to him that led to their seven-hour phone call.

Debbie had reached out to Don before Hae’s body was found. It’s worth noting that in the interviews Don gave to Baltimore County Police and the investigator Mandy Johnson, he doesn’t mention the possibility of Adnan’s involvement in Hae’s disappearance. It may have been that early on he didn’t realize that she had truly disappeared, assuming she had gone to California, but later, when it became clear that something was very wrong he began to think Adnan was involved and told Debbie so. The seven-hour phone conversation is a little harder to explain—especially in light of an undated police note that reads: “None of Hae girlfriends like new boyfr. New boyfriend assaulted Debbie.”

The only new boyfriend Hae had was Don. But nowhere else in any of the files is this assault by Don explained.

* * *

Because the police didn’t begin interviewing most of Hae’s classmates and teachers until long after she disappeared, and after Adnan’s arrest, the statements they give end up conflicting on a few points, one major one in particular—when Hae actually left school.

Becky recalls seeing Hae leaving school immediately after dismissal, around 2:20 p.m., when she tells Adnan she can’t give him a ride. But about a month earlier, Debbie told Detective O’Shea she saw Hae leaving close to 3:00 p.m., saying she was going to see Don at the mall, though Debbie didn’t actually see her leave school.

Inez Butler, the school athletic trainer, backs up Becky’s recollection in a police interview when she says Hae pulled up to her concession stand in the bus loop to grab Andy Capp Hot Fries and apple juice. According to Butler in a March 23 interview, this happened around 2:30 p.m. the day Hae disappeared.

The police only get two statements about where Adnan was around the end of and after school that day. The first is from Debbie, who recalls seeing him at the guidance counselor’s office picking up a letter of recommendation around 2:45 p.m., dressed and ready for track practice. The second is from Coach Michael Sye, Adnan’s track coach, who says in his March 23 police interview, “Ms. Graham lets them go from study hall, they change, come to track. I usually arrive around 3:30. From what I remember he was there on time, left on time.”

The police weren’t able to get information that would tie Adnan to the crime from anyone at Woodlawn, but they did think there was another set of people who might be able to tie Adnan to the crime.

Of Adnan’s Muslim friends who were questioned (including Nisha because they couldn’t distinguish between Muslim and Hindu), all were asked if he had told them anything about the murder—but none of his non-Muslim school friends were asked that.

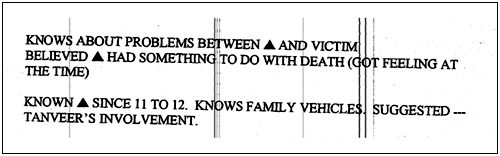

Of particular interest to the police was Yaser Ali, the same person thought to have been referenced in the February 12, 1999 anonymous tip. Yaser, an old family and childhood friend of Adnan’s, had grown apart from him in the last couple of years. He knew Adnan was dating but was disappointed by the fact that he was having sex. Though he didn’t attend Woodlawn High, Yaser knew Hae, had met her at a party. He also knew Jay, whom he saw at a party in late January, but Yaser also had gone to school with him for a couple of years in the past.

The interview notes, taken on April 8, seem to suggest Yaser had already spoken to Detective MacGillivary once before, though no record exists. He also mentioned that he had been contacted by Andrew Davis, a private investigator working for Adnan’s attorney.

A couple of things Yaser said put holes in the cops’ case: first, that Adnan had been looking for a cell phone for months, contradicting the idea that he had gotten it specifically for the murder, and second, he denied everything attributed to him in the anonymous call.

Though he didn’t have any knowledge of the crime, the police were able to get this information from him:

Inexplicably, in the same notes is a handwritten section that says: “Tanveer—older brother, student @ Towson State, pretty straight guy.”

How Yaser would both state that Tanveer is a “straight guy” and at the same time imply he had some involvement with Hae’s death is hard to reconcile. It didn’t seem that the police took it seriously, though, since there’s no evidence that they investigated Tanveer at all.

The police struck out with Yaser, but they tried hard to find someone in the Muslim community that Adnan may have confessed to or confided in. The implication is striking: Muslims were the kind of people who would quietly accept and cover for the murder of a young girl—much as Wash was implying at the bail hearing.

The suspicion of the Muslim community was so deep that after local Pakistani activist Alfreda Gill visited the school with Adnan’s father to collect Adnan’s school work to deliver to him in jail, a school official took down her license plate number and immediately informed the police of this suspicious character. That one act of kindness on Gill’s part earned her the prize of having her phone records subpoenaed by the police on March 24, 1999, five days after the visit. In fact, the list of people who had their phone records subpoenaed is exclusively Muslim: Gill, Bilal Ahmed, Adnan, and my brother Saad. Jay Wilds’ and Jenn Pusateri’s phone records are not subpoenaed, and neither are the records of the people Jay called on Adnan’s phone on January 13: Phil Mendez and Patrick Furlow.

Even the kinds of questions posed by jurors in the grand jury to Saad and Bilal Ahmed indicate that they were well aware of the State’s theory of the case—that this was a religiously sanctioned murder. Not having the full transcript of these confidential proceedings, we can only imagine what the opening statement by Wash must have been like to produce questions with such suspicious and disturbing pretexts.

Among them:

“In the Islamic community, suppose a young adult goes to an adult that he respects, a mentor, and confesses the same thing, that he has committed a terrible crime … is there a particular course of action that is dictated by the Islamic faith for that mentor? Would he be required to notify the civilian authorities?”

“I have one more question. You stated before in your community you have no punishment for dating per se. Is there in the Koran a punishment for dating or marrying outside of the Islamic faith?”

Ahmed was also asked about his immigration status and command of English and why he hired an attorney. Clearly, the jury was suspicious of him as someone who might be keeping a confession by Adnan secret.

The line of questioning about Islamic punishments for dating and sex are still confounding to me. Is it the State’s theory that these punishments are meant for the person who a Muslim is dating, which seems the implication, given the allegation that the community would hide or support Adnan’s killing of Hae? Or that Adnan risked some terrible religious punishment for dating Hae, and when he was dumped he was angry that he risked it all for nothing? Regardless, it wasn’t just Adnan being indicted at this grand jury proceeding, it wasn’t just him being investigated and prosecuted. His faith, his ethnicity, even his community—they were all on trial.

It would be up to Gutierrez to defend us all.

* * *

Gutierrez met with the community group that had formed at the mosque to help organize Adnan’s defense twice that summer as she prepared for the trial. Each time, in response to the many questions about the likelihood of success, she emphasized one thing: it was the State’s burden to prove Adnan did it. And from what she knew there was little evidence to support the charges. As long as she was able to poke enough holes in the case, she’d win. It was about reasonable doubt, after all.

Saad spent almost an entire week with Gutierrez when she was representing him and Bilal for the grand jury proceedings, and he would repeatedly press her on how to go about Adnan’s defense.

“I would tell her, hey Adnan was seeing other girls, you need to call them, and are you going to get the DNA tested, and he was definitely at the mosque that night so you gotta find others who saw him, and what about video cameras, maybe he was on video somewhere like at the school or mosque,” Saad said, exasperated.

Gutierrez listened but her response was the same: it’s not our burden to prove anything. Stop worrying.

Before she was hired, Colbert and Flohr had already begun doing what attorneys should—building a defense for their client.

Defense Private Investigator Andrew Davis first entered the scene on March 4, 1999. He met with Flohr and Adnan a few days after Adnan’s arrest. The first order of business in this case was obvious: establish where Adnan was after school on the day Hae disappeared. There are no notes of Davis’s interview with Adnan, but the very same day he went to meet Coach Sye, an indication that Adnan must have told him he was at track practice that day. Unfortunately, there is no definitive confirmation by Sye that he was definitely at track on the 13th, but he did say that Adnan was at track the majority of the time. He medaled in track, and would have gotten a varsity letter if he hadn’t been arrested, according to Sye.

Most importantly, the notes say “3:30–4:30-5:00,” indicating that track began at 3:30 and ended between 4:30 and 5:00 p.m.

* * *

About a week later, on March 10, Davis interviews Jay’s boss, a woman only ever identified as “Sis,” who tells him that Jay was hired around January 24 and was supposed to begin training the very next day. But he didn’t show up from the 25th through the 27th of the month. His first actual training day ended up being January 31. Sis told Davis that Jay would usually get rides to work, not having his own car, and gave him a rundown of his working hours through February and March.

Sis noted that the police had come by several times to speak with Jay and she eventually asked him if it was in connection with the “girl found in the park.” He said yes. He told her that he knew who killed Hae, stating that “no one thinks he did it but he did kill her.”

That same day Davis also interviewed one of Adnan’s closest friends and fellow Magnet Program student, Stephanie McPherson. Stephanie was so close to Adnan that it may have been a point of discomfort for her boyfriend, Jay Wilds.

Stephanie was another overachiever—smart, driven, athletic, and headed for a bright academic future. Her boyfriend, on the other hand, was not who her parents had in mind for her. Jay was in many ways from the wrong side of the tracks. Stephanie came from a solid middle-class home and had parents who demanded excellence from, and for, their daughter. The future they envisioned for her didn’t have someone like Jay in it, and he was painfully aware of that. But Stephanie loved him and they dated throughout high school.

Adnan and Stephanie had been classmates and friends since middle school and had an ongoing flirtation that never got further than that. Adnan considered Stephanie to be one of his closest friends, but things changed a bit when he began dating Hae—Stephanie didn’t completely approve.

Still, they continued to hang out, darlings of the other students who had named them junior prom king and queen the prior spring.

Now, however, a wall had come down. Stephanie had not reached out to Adnan or his family since his arrest, though other students like Asia had visited his home. According to other students, she went on emotional lockdown, refusing to talk to anyone about anything related to the case.

She did, however, speak to PI Davis twice. The first time was at her home in the presence of her parents. In this interview Stephanie notes that Adnan “is one of my best friends.” She had known him since grade school, but she had only met Hae during their freshman year in high school. She had found Adnan and Hae’s relationship “odd” because she found Hae to be shallow, but also odd because of Adnan’s religious beliefs. She said that in November or December of 1998 Hae became strange because she had a new boyfriend and that Adnan “was said to be upset because he didn’t see it coming.” She said while Adnan wanted to meet Don to size him up, he was happy that they had broken up because now he didn’t feel guilty talking to other girls and hanging out with his friends. She remembered when Adnan got his cell phone and said they spoke nearly every night on the phone.

On the day that Hae went missing Stephanie recalled getting a birthday gift from Adnan, a stuffed reindeer, and that Hae was very quiet at lunch. Nothing else unusual happened that day, and she left school at around 2:15 p.m., arriving home at 2:55 and then returning for a basketball game around 3:30 or 3:45 p.m.

The day Hae’s body was found, on February 9, she said she spoke to Adnan on the phone and then he came over to her house along with a number of other friends. Hae’s brother called them and confirmed that Hae had been found, and Adnan immediately said they should call the detective because he didn’t believe it. As Adnan was crying, they attempted to contact O’Shea and ended up leaving him a message.

Stephanie told Davis that there was no talk in school at all about Adnan being involved in Hae’s death until he was arrested, but that her boyfriend Jay told her he had personal knowledge of Adnan’s culpability and that he’d also told her that Adnan had threatened Stephanie as well. Stephanie also stated that she “did not believe that Adnan would ever threaten her but she believed her boyfriend of many years, Jay, was an honest person.”

Stephanie doesn’t report anything unusual in this interview, other than the threat Jay says Adnan made toward her, and one other thing—that while she spoke to Jay late on the night of January 13, she didn’t actually see him that day. This contradicts both Jay and Jenn, who say they went to Stephanie’s house that night so Jay could wish her a happy birthday. As for the threat, it seems clearly false to me: Stephanie knew nothing of Adnan’s connection to the murder or his alleged threat until after he was arrested, meaning until after Adnan couldn’t reach or harm her anyway. If the threat were real, why would Jay allow Stephanie to hang out with Adnan and speak to this alleged murderer on the phone every single night? The threat Jay brings up after Adnan’s arrest seemed to be a mechanism to keep them from communicating ever again.

The very next day, on March 11, 1999, a memorial service was held at Woodlawn High School for Hae. Adnan had a hand in organizing the event (it was his responsibility to purchase a tree to plant in Hae’s name as well as draft a speech to give) but he missed it because of his arrest.

The memorial was held in the school gymnasium, and Davis showed up to try and get some interviews with students. The only one he was able to connect with was Stephanie, whom he had just spoken to the night before. This time she added a detail she hadn’t mentioned before: between 4:15 and 5:30 p.m. on January 13, she had called Adnan on his cell while waiting for her basketball game to start, and Jay was with him at the time.

The night before the memorial, when Davis had been interviewing Stephanie, Jay showed up at the house, knowing Adnan’s PI was going to be there. Her parents had turned him away but he was told to return later. Undoubtedly their conversation was about Adnan and Jay’s involvement in the case, and the importance of Jay being placed with Adnan that late afternoon. Maybe Stephanie thought she would be helping her boyfriend with this additional detail, or maybe Jay asked her to say it. But not only does Jay never mention such a phone call in any of his statements, past or future, according to Coach Sye, Adnan was most likely at track practice at that time.

This invites the conclusion that Stephanie is willing to do what it takes to protect Jay from the defense investigation, but she isn’t willing to lie to the police for him. If she had, she certainly would have been a prosecution witness as someone who could corroborate Jay’s story. But Stephanie—the only person in the story who is so close to both of these young men—never again makes an appearance in the case after her interviews with Davis and the police.

Stephanie may have had her boyfriend’s back but Adnan, one of her best friends, is on his own now. He’s the only one who can prove where he was after school on January 13, 1999.