The Prophet said thrice,

“Should I inform you about the greatest of the great sins?”

They said, “Yes, O Allah’s Apostle!”

He said, “To join others in worship with Allah and to be undutiful to one’s parents.”

The Prophet then sat up after he had been reclining and said,

“And I warn you against giving false witness,

and he kept on saying that warning till we thought he would not stop.”

Sahih ul Bukhari, book 52, hadith 18

As Adnan waited in prison for the trial, my family and I did the only thing we knew how to do—we tried to keep his morale up. Adnan did the same thing with us, never once discussing details of the case or the tremendous stress he was under. We all acted like this was a temporary thing.

Adnan would tell funny stories of people he met on the inside, to distract us. He was terrified. But he never let any of us know. All around, it was a carefully orchestrated dance to avoid more pain than anyone could bear.

It wasn’t always easy for him to hide his feelings, though. Once in a while, the pain would jump off the pages of his letters. When he received his high school diploma in a ceremony at the prison, his sadness was clear in a letter he wrote to me:

6/21/1999

Dear Rabia,

Asalaamulaykum. How is everything w/ u and ur family? Fine, I hope. It hasn’t been hot the past week or so, and the temperature in here has been pretty nice. Sometimes it gets kinda chilly, but I’d rather have it be cooler than hotter. Hopefully, it’ll last 4 awhile.

I received my diploma on the 11th. It was kinda nice, it was during the function held for the end of the school year. It was nice, they called my name, and I went on stage and received it, + shook the hand of the school principal. A lot of people clapped + cheered, so it made memorable. It’s weird though, cause there were a lot of cameras flashing, and a lot were for the PR dept. they have in here. I was really happy that my parents were there though. I know it meant a lot to them for me to receive my diploma. I guess it’s a memorable event for every parent. Honestly though, it didn’t mean so much to me as it would’ve if all this stuff hadn’t happened. I mean, I really appreciate the trouble the teachers went to get my diploma, and I’m grateful that my parents were there, but to me it really was just a piece of paper. (actually, an italicized jacketed certificate). I guess while some people would look at it + say this is 12 years worth of work; I think that my mind is 12 years worth of work (actually 18). In the beginning, I used to think, man, they took my graduation day away from me. But now, it’s like, all those years are shown in my head, not on a piece of paper, and they can never be taken away from me. I’m really glad my parents were there, though.

You know what, I’ve developed a liking for crossword puzzles. Not w/clues, but the word searches. I don’t know if you could send me a book, but maybe if you just sent the pages, do you think u could find some for me? Not little kid ones, but sometimes u can find them in little kid magazines, or they probably sell crossword puzzle books. If you get the chance, do you think you could send me some. I don’t think they would fit in a small envelope. So maybe you could send them in a 8"x11" envelope. I think they’re called manilla envelopes. I go through them pretty fast, so as many as you could send I would really appreciate it. Not the kind w/ clues, though, cause it’s really frustrating if you can’t figure them out, and there is no answer key.

I hope your exams went well, and so is everything else. Take care, give Sunnah a hug for me.

—Adnan Sayed

As we all feigned ignorance about the enormity of the situation, Adnan and his defense team were busy trying to nail down the seminal questions: where was Adnan (and how could they prove it) from after school on January 13, 1999, until he went to the mosque for Ramadan prayers that night, and why would Jay implicate him in Hae’s murder?

Gutierrez’s files show that Adnan was grappling with these issues but initially seemed to have a decent grasp of exactly what happened during the day. Not all of his attorney visits are documented, but there are numerous notes in Gutierrez’s handwriting that show Adnan had discussed Asia.

One note reads in part: “Asia and boyfriend saw him in library 2:15-3:15. Went to library often. 3:30 practice started.”

The notes confirm that Adnan remembers seeing Asia and her boyfriend at the library and also reflect something else that becomes very important at trial: that track practice began at 3:30 p.m., as Coach Sye indicated to detectives and PI Davis earlier. So Adnan would have had to get dressed in time to be there by 3:30. This narrows the window of opportunity for the crime to have been committed by Adnan.

The notes are undated, but we know from prison visitor logs that Gutierrez met with Adnan on May 28, June 5, June 26, and July 10. The latest they could have been written was July 10, months before the defense or Adnan know anything about Jay’s timeline, who puts track practice later.

Asia comes up again in these notes, dated July 13, 1999, taken by Gutierrez’s law clerk during a visit with Adnan:

Adnan’s schedule for January 13, 1999, is clearly laid out, including the time he spent at Jay’s house. Most importantly, though, is the notation about Asia McClain: “saw him in the library @ 3:00, Asia boyfriend saw him too; Library may have cameras.”

Again, at this point neither Adnan nor Gutierrez know the State’s theory of the case—they have no idea what Jay has said about when Hae was killed. But they do know she disappeared sometime between school and when Adnan got the phone call from Officer Adcock around 6:00 p.m. that day. So independent of any knowledge of when Hae was killed, Adnan has already established a firm alibi for that exact time.

About a month later, on August 21, a law clerk takes more notes during a visit with Adnan that reiterate his recollection: “States he believes he attended track practice on that day because he remembers informing his coach that he had to lead prayers on Thursday.” He also recalls that when Hae’s brother called on the evening of January 13, he was with Jay in his car, recalling “reaching over Jay to get the cell phone from the glove compartment.”

He also provided a handwritten account of his recollection of the school day.

There is a marked difference in these notes and the ones from July—there is no mention of Asia. By this time, having given Gutierrez Asia’s letters and repeatedly asking her to speak with her, Adnan has given up on Asia. Gutierrez told him that she had checked with Asia, but Asia had her dates wrong; she hadn’t seen Adnan on January 13 after all.

Adnan was confused, he was sure it must have been that day because he also remembered the following two days of school being closed, the days right after Hae went missing. Asia’s letters had jogged his memory; he remembered teasing his friend Justin Adger, Asia’s ex-boyfriend, about seeing her with her new man. And he was certain this happened right before the big storm in January that shut everything down for a couple of days.

He could have called Asia himself. He didn’t, though, because Gutierrez had strictly warned him against talking to too many people, kids at the school in particular. It’s not clear why, but she may have worried about his calls and mail being monitored or that he could be accused of influencing potential witnesses.

There were two important time frames he had to account for: the hour or so between school and track practice, and the time between track practice and the night prayers at the mosque. He was sure that he was there the night of the 13th because he had to lead prayers the next day. Gutierrez had spoken to a few people in the community who also remembered that Adnan led prayers on January 14, including the president of the mosque, Maqbool Patel, and his son Saad Patel. It’s considered an honor for a young man to get to lead prayers for the first time, and it was a meaningful day for Adnan, his family, and others in the community.

Adnan didn’t think he had to worry about the evening anyway; everyone knew Hae went missing right after school. That was the most important time to account for, and he wasn’t able to do it. He had no alibi. It was in those days, as he spent time with other inmates who filled his head and heart with fear that beating such serious charges was nearly impossible, that he began thinking about the possibility of a plea deal. Asia was gone, he had no alibi, he had no idea what evidence the State had against him, or what was in Jay’s statement to the police. He had spent time with Jay during the morning when he dropped off the car, and after track practice when they grabbed some food and smoked some weed. If he had no way to prove that’s all they did, Jay could say whatever he wanted. It would be his word against Adnan’s.

After all, Jay had Adnan’s car that day. It was Stephanie’s birthday and Adnan let Jay borrow the car to make a mall run for a present. It wasn’t the only reason he gave him the car, though; Jay got him weed. He didn’t particularly like Jay and wasn’t friends with him, but he was, simply put, useful. He had to hang out with Jay every so often anyway, because of Stephanie, so he might as well get something out of it. Jay had connections none of Adnan’s other friends had, to get cheap pot. Jay also did a little dealing, and if Adnan let him borrow the car (and sometimes money), he might get a bit of a kickback, or at the very least, free weed.

Jay also had Adnan’s phone on the 13th.

Adnan couldn’t take the cell phone to school so he left it in the glove compartment on January 13th, and it was with Jay all day, just like his car was. Jay could have used his phone, and his car, in any way while he was at school; he might even have gotten to Hae that way, which explained why he was framing Adnan for the murder. Adnan had no idea where Hae went after she left school, but she had his cell phone number. What if she had called it and connected with Jay instead? What if she met up with him and he killed her?

But why would Jay hurt Hae? Adnan had one theory, though even he didn’t really believe it.

Jay had been cheating on Stephanie. Jay had told him about another girl he was seeing, his “booty call,” while Stephanie was at school or basketball. He had one regular girl he would hook up with, but there were other random girls too. During an assembly in school about a year prior, Stephanie had told Adnan she was going to swing by Jay’s house, and he had talked her out of it. He knew Jay had one of his girls over, the girls he called “ghetto white girls.”

Adnan didn’t understand it, because Jay was crazy about Stephanie. He couldn’t imagine his life without her. Would he kill someone who threatened that prospect? That’s what Adnan worried about. Because he had made the mistake of telling Hae that Jay was sleeping around, and she was livid. She’d told him that she’d confront Jay about it, that Stephanie needed to know. But Adnan begged her not to. He knew it would wreck Stephanie’s heart. He figured that next year Stephanie and Jay would break up anyway, once she went away to college.

Adnan, said Hae, was thinking like a guy. It wasn’t fair to Stephanie, but Hae agreed not to say anything. She and Stephanie weren’t that close, and she realized that being the one to break such news could backfire—Jay could deny it and then Stephanie would hate her and Adnan.

But what if Hae changed her mind? What if she inadvertently connected with Jay using Adnan’s phone and just couldn’t hold it in?

This thought plagued Adnan.

That’s why, in Gutierrez’s undated notes from her visit with Adnan, it says at the top, in reference to Stephanie, “Jay—if anyone ever tried to get between her & I, I’d kill him.”

But of course, Adnan had no proof. The state refused to turn over Jay’s statements. All Adnan knew was that up until around 8:00 p.m., when he was at the mosque for prayers, he had no one to vouch for him. In a nutshell, things weren’t looking great for Adnan.

Still, said some of the jailhouse F. Lee Baileys, the State almost always offers a plea deal. Especially to someone like him, who had a clean record and was a juvenile. The State was going hard but if all they had was a witness and no other evidence, they probably also knew their case wasn’t rock solid.

So Adnan asked Gutierrez, as the trial date of October 14, 1999, approached, whether the prosecutor had offered a plea deal. She said, categorically, no. They had said nothing.

Well, then, could she approach them and ask if they’d consider it?

She said she would.

Adnan never told any of us that he did this—he knew that everyone, the family and community, would be in an uproar. None of us could fathom the idea that he would or should spend twenty, ten, or any years at all in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. But none of us were in his shoes. He knew that if he didn’t win at trial, he would spend the rest of his life in prison.

“A couple decades, man, and you’ll still get out young. You still got your life. That, or you die in here,” was the message he was getting from other inmates.

He waited anxiously for her answer, thinking the State would definitely make an offer. He’d figure out how to deal with the rest of us, how to explain it to his family and friends, later.

But he never had to because when Gutierrez came back to him she repeated what she said before. There was no offer on the table, the State said no.

If there was ever a time to worry, this was it. If the State wasn’t interested in a deal, it could only mean one thing: they had the evidence to put him away forever.

* * *

Baltimore City Police were indeed doing their best to gather evidence against Adnan. On March 9, 1999, the cops executed a search warrant on Adnan’s car.

Every loose item was retrieved from his car, including the trunk lining, to be tested for traces of blood, hair, or other DNA sources linking him to the crime. Samples of soil and leaves were also taken—presumably to match with soil and leaves from Leakin Park.

The police had already taken vacuum samples of soil from different parts of his car on the day they seized it, the same day they recovered Hae’s car. All items from Hae’s car were also collected and catalogued: a $10 checking withdrawal receipt dated 1/10/99, a credit card receipt from a gas station, a woman’s school ring with no stone in it, Almay hand lotion and Mystic perfume spray from her purse, a plastic hanger, a red Big Gulp cup, a red ink pen, a blue ink pen, banana flavored lip balm, a package of maxi-pads, three stuffed animals including a Tweety Bird, a pair of black socks, a “happy birthday” paper crown, a size 7 pin-striped miniskirt, Nike cleats, a card with pictures of currants, a paystub for Adnan Syed dated 11/13/98, a folded note made out to “Don,” a pack of index cards, six pictures of flowers, a thank-you card made out to the Lee family, a medium cotton T-shirt with short sleeves, a multi-county map with a pages 33 and 34 missing, a striped short-sleeved shirt with possible blood on it, a vehicle registration and insurance, a Baltimore Zoo map, a dried rose and baby’s breath in a wrapper, a mango drink, an empty apple drink box, black dress heels, an empty gift box, a hockey stick, a gold heart charm with attached $119.95 price tag, a University of Maryland admissions card, and her Eastpack blue book bag with miscellaneous items including a copy of Othello, a senior portrait order form, various photographs, and a high school agenda with Don’s name written all over the first page.

A hair sample taken from the front right floor between the seat and the door and seventeen vacuum samples were also taken from Hae’s car.

The prints found in Hae’s car were compared to Jay’s and Adnan’s, and while there wasn’t a single match for Jay, Adnan’s prints appeared three times in her car: a partial palm print on the rear cover of the map book, on an insurance card in her glove compartment, and on floral paper wrapped around the dried rose and baby’s breath.

Considering the fact that Adnan had been in Hae’s car dozens of times, his prints should have been everywhere. The fact that they were not seems to suggest the car had been wiped down for prints when it was dumped, but the person who wiped it down didn’t think to wipe down less obvious things—like paper.

Sixteen other prints found in the car were run through a database with no hits. Two of those appeared on the car’s rearview mirror. These prints were compared against Adnan’s, Jay’s, Hae’s, and a criminal database, with no luck, but prints were never taken from Don or Hae’s family members.

According to State disclosures, “about 40” hairs were recovered from Hae’s body and clothing. The majority were Hae’s but two were not. Those two also didn’t match Adnan’s. Three hairs recovered from Hae’s car weren’t tested at all.

The soil samples taken from Adnan’s and Hae’s cars, and Adnan’s home, clothing, and shoes, were all compared against soil samples from Leakin Park. Given Jay’s narrative, having trudged through Leakin Park in the dark, dug a grave, and gotten back in both cars with dirty shovels and shoes, some dirt or soil from the park should have been present in the cars or on Adnan’s clothing and shoes. But nothing matched. There was no soil from Leakin Park anywhere to be found.

A T-shirt found in Hae’s car, which turned out to be her brother’s, appeared to have a small amount of blood on it. Testing showed the blood matched Hae’s and no one else.

The clothing Hae was wearing was examined for spermatozoa, but the lab found nothing. And then there were the swabs taken from Hae’s body. The lab report indicates six of them were not analyzed, a very odd move considering that these items, listed in the lab report, consist of nearly every potential source of perp DNA from Hae’s body: the vaginal, anal, and oral swabs, pubic hair sample and combings. Similarly, a brandy bottle retrieved from the crime scene had skin cells on it that were never tested for DNA, and neither was a thin, white rope recovered from within inches of the body.

Fingernail clippings tested were returned with results that read “nothing of evidentiary value was detected.”

The lack of sperm is not as telling as it may seem, though. To be clear, examining clothing for semen is not the same as running a DNA analysis. According to the autopsy, along with Hae’s clothing, the oral, vaginal and anal swabs were tested for spermatozoa and returned negative results. But there are two glaring issues here: first, sperm is not the only source of DNA. The medical examiner was only looking for signs of rape or sexual activity by seeking sperm traces. Second, they were using a common phosphate enzyme test to check for the presence of sperm—a test that can only detect sperm within roughly a hundred hours of sexual activity; if Hae had been raped or otherwise had sexual activity on the day she disappeared, this particular test would be useless to determine it.

At the end of the day, other than the partial palm print on the map book, a book Adnan had used many times while in Hae’s car, the State found no physical evidence tying him to the crime scene or her body. Or, for that matter, tying Jay to any of it either. And for some reason, the State put a hold on the DNA testing.

During the police’s search of Adnan’s home, executed on March 20, they retrieved his clothing and shoes, the boots they believed he had worn while committing the crime. But they also turned his room upside-down looking for any other evidence of his plans to murder Hae. In doing so, they came across a psychology textbook on Adnan’s bookshelf crammed with cards and notes from Hae, and pictures of them together. It was his secret stash of relationship memorabilia. In that stash was a note from four months prior, the note written by Hae to Adnan right after she broke up with him because of the homecoming dance fiasco.

Back in November, the note had lingered in his binder, and he showed it to Hae’s best friend, Aisha Pittman, during health class one day when they were discussing pregnancy. On the back of Hae’s note they began writing notes back and forth to each other, messing around about whether Hae was pregnant. Aisha was friends with both of them, and there was no hiding anything from her.

The police didn’t care much about the banter. What caught their eye were the words written in Adnan’s handwriting across the top of his exchange with Aisha.

Note traded between Aisha Pittman and Adnan in November 1988, admitted to evidence at trial

* * *

An ambiguous line written on a four-month-old note and no forensic proof does not a conviction make, so the State was spending a considerable amount of time making sure their key evidence was not only solid, but solidly tied down. That evidence was their star witness, Jay.

Since his first recorded police interview on February 28, 1999, hours before Adnan’s arrest, Jay had given three more interviews on the record.

Jay’s second interview was at 6:00 p.m. on March 15, at the Baltimore City Homicide office, and this third interview happened three days later, on March 18, complete with a “ride-along” where the police took Jay out to recreate the events of January 13. The fourth interview was conducted on April 13, 1999, but no record of that interview exists anywhere in police or defense files. The only indication it even took place is a short memo noting it.

While the first interview already had internal inconsistencies, the second and third added layers and layers of confusion and contradiction.

In the second interview, Jay now said he knew how Adnan killed Hae, telling MacGillivary: “He tell me that ah, he’s going to do it in her car. Um, he said to me that he was going to ah, tell her his car was broken down and ah, ask for a ride. And that was, and that was it, that.”

The story of Adnan asking for a ride comes, notably, after the police have heard this from Krista Meyers on February 29, a couple of weeks earlier. Neither Jay nor Jenn knew, when questioned earlier, how Adnan got hold of Hae to kill her.

This time Jay also said that during a previously unmentioned store run with Jenn as he awaited Adnan’s call, he told her that Adnan was planning on killing Hae that day. Jenn had said no such thing, maintaining that she didn’t know any of this until that night when she picked up Jay. But then, the first time Jay had spoken to police, he had told them that he didn’t know of Adnan’s plans until the day it all went down. In the first interview Jay said he went to the Westview Mall to buy Stephanie’s gift; in the second he said he went to Security Mall, both located in the suburbs of the city.

Hundreds of small inconsistencies like this pepper Jay’s interviews, and a few big ones stand out, for example, where it was that Adnan showed him Hae’s body. In the first interview, the “trunk pop” to reveal Hae’s body happens on Edmonson Avenue. In the second interview it happens at Best Buy. By the third interview Adnan has killed Hae in Patapsco Park but he doesn’t show Jay the body. The trip to Patapsco Park also jumps around, at 2:15 p.m. in one interview, at 4:30 p.m. in another. In the first interview he is at Jenn’s home, which she confirmed, when Adnan’s “come and get me call” comes in. By the third interview he is driving home when the call comes.

In the first interview, only Adnan buries Hae. In the second, they both do. In the first interview, Jay disposes of his clothing in the trash cans at his own house; in the second he gets rid of them at the F&M store dumpster.

In the second interview Jay visits the apartment of a girl named Kristina Vinson three times on January 13; in his first interview he doesn’t visit her at all.

Whether and where Adnan smokes pot, where they get the pot, if and where they eat, who Jay visits during the day on the 13th, all of these details change with each interview, and sometimes within the same interview. Jay describes Adnan removing Hae’s items from her car and putting them in his car in two different locations in the second interview: at both the I-70 Park-n-Ride and at Edmonson Avenue.

One consistency between the first and second interviews, an important one given the way the State’s case is going to go, is that the call Adnan made to “come and get me” came to Jay around or after 3:30 p.m., and that he didn’t leave Jenn’s house until around 3:45 p.m.

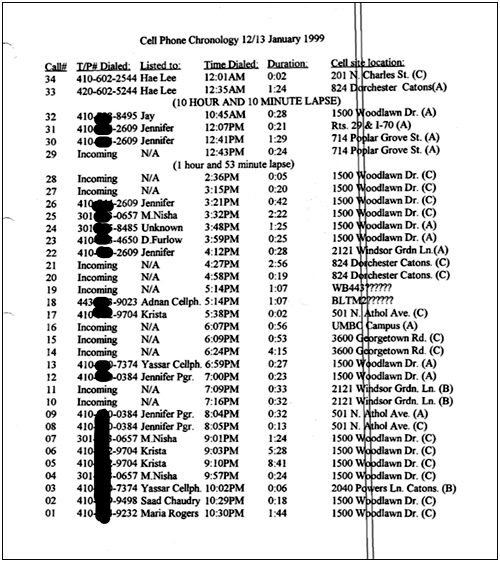

Another consistency is the constant referrals to cell phone calls, their timing, his location during the calls, and the content of the calls. The calls to Adnan’s cell phone, which Jay had all day, are unmovable. Their records are fixed and they must be dealt with; Jay’s statements have to work with and around them. And to the best of his ability, he seems to do that. Over and over he’s asked about different calls, and two undated documents titled “Jay’s Chronology” and “Cell Phone Chronology,” found together in police files with notes from his March 18 police meeting, seem to indicate that they worked with him to get his stories to match the record.

The cell phone records solve one of the State’s big problems—most of the varied, and changing, details of Jay’s statements are unverifiable. Jay’s testimony and corresponding cell phone records will become the basis of the State’s case at trial, in particular a 3:32 p.m. call to Nisha Tanna (the girl Adnan had met at the New Year’s Eve party) and the 7:09 and 7:16 p.m. incoming calls. But first they have to make sure they can get Jay to the trial.

Throughout his interviews Jay has, repeatedly, implicated himself as an accessory to a very serious crime. He knows he needs an attorney but can’t afford a private one, so he does the next best thing—he contacts the Baltimore public defender’s office asking for a lawyer. He hits a wall, though—he doesn’t qualify for a public defender because he hasn’t been charged. And he continues to be in that limbo, implicated but not charged, until September 7, 1999.

On that day, prosecutor Kevin Urick finally charged Jay as an accessory after the fact to first-degree murder. But Jay did not need to worry. The charges were not just filed nearly concurrently with a plea deal he was being offered, but also at the same time that he finally got an attorney, albeit in a highly irregular manner.

Attorney Anne Benaroya had recently entered private practice after seven years as an assistant public defender in Baltimore, Maryland. In September of 1999 she was working with a boutique criminal law practice and was occasionally asked by prosecutors to speak with indigent defendants. On that particular day she had a jury trial against Urick that ended sooner than expected. As they wrapped up Urick asked her to speak to a young man who needed an attorney. She was qualified to be a court-appointed pro-bono attorney, so she agreed.

Jay was being offered a plea deal, right then and there. Upon speaking with Jay she realized that he was already “loaded with prior statements to BPD,” in her words, and that the plea was a foregone conclusion. If he didn’t take the plea, Urick implied that the case could be tried in mostly white Baltimore County where a defendant like Jay wouldn’t fare so well. Benaroya realized that, having tangoed this long with BPD, Jay was actually lucky he was getting a deal at all. Urick didn’t have to offer him anything; he could just subpoena him based on his existing statements. Of course, an uncooperative witness can do plenty of damage at trial.

The plea was the bargaining chip used to make sure Jay testified as needed, with the threat of imprisonment hanging over his head, but to enter a plea Jay needed to have an attorney. Urick couldn’t parade him before a judge without legal representation. Lucky for Urick, and Jay, Benaroya had the heart of a public defender and couldn’t say no. But at that point Jay hadn’t been arraigned yet, so Benaroya asked the court to proceed with the arraignment in order to enter her appearance as his attorney as well as to enter his plea.

The parties then immediately entered a plea before the court, with Jay pleading guilty to one count of accessory after the fact to the murder of Hae Min Lee.

According to the plea, as long as Jay cooperated by continuing to “tell the truth,” the State would recommend a five-year sentence with all but two years suspended. However, when Jay is finally sentenced the following year, this is not the sentence he gets.

* * *

With Jay’s testimony secure, the State now has to deal with Gutierrez and her barrage of discovery requests. While the State ostensibly has an “open file” policy that would allow defense counsel to have full access to prosecution files, Gutierrez was forced to file demand after demand to get information about the charges.

As of September 1999 the only information given to the defense is what was contained in the indictments and warrants from months ago:

On 09 February 1999, at approximately 2pm., the Baltimore City Police Department responded to the 4400 block N. Franklintown Road, for a body that had been discovered by a passerby. Members of the Armed Services Medical Examiners Office responded and disinterred the remains. A post mortem examination [ruled the] manner of death a homicide. Subsequently, the victim was identified as Hae Min Lee … On 27 February 1999, your Affiant along with Detective William F. Ritz had the occasion to interview a witness to this offense at the offices of homicide. This witness indicated that on 13 January 1999, the witness, met Adnan Syed at Edmondson and Franklintown Road in Syed’s auto. Syed, who was driving the victim’s auto, opened the victim’s trunk and showed the witness the victim’s body, which had been strangled. This witness, then follows Syed in Syed’s auto, Syed driving the victim’s auto, to Leakin Park, where Syed buries the victim in a shallow grave. Subsequently, this witness then follows Syed, who is still driving the victim’s auto, to a location where Syed parks the victim’s automobile. Syed then gets into his car and drives the witness to a location in Baltimore county where the digging tools are discarded in a dumpster.

Gutierrez had been attempting since May to compel full discovery on the details of the case, including repeated filings for the autopsy report and Jay’s statements. At one point she contacted the medical examiner’s office herself to get the autopsy report only to be told that they’d been instructed by the prosecution not to provide it to her.

Although Gutierrez already knew the identity of the State’s witness because the police had told Adnan who it was during his interrogation, the State filed a motion with the court to bar discovery of the witness’s ID. In response to Gutierrez’s request in June for “[a] copy of any statements made by Jay Wilds as an unindicted co-conspirator or codefendant,” the prosecution replied that “[t]here is no unindicted co-conspirator or co-defendant.” Technically, the State was right—they hadn’t yet charged Jay.

It is not until about a month before the trial is scheduled, on September 3, that the State discloses it has Adnan’s cell records and intends to introduce them at trial as business records.

On the same day that Jay pleads guilty to accessory after the fact, Gutierrez files a motion to compel further discovery with the court, asserting that the defense hadn’t been given enough information to raise an alibi defense.

Moreover, the State has identified, only upon inquest by this Court, that Ms. Lee was murdered sometime in the afternoon of January 13, 1999, but the State has contended it cannot establish the time of death with any further precision. Jay Wilds, according to the State, met Adnan Syed directly after the murder at a prearranged time and location and was present and assisted in the burial of Ms. Lee’s body in Leakin Park. While the State has “paraphrased” Mr. Wilds’ statements for various purposes, the State has not “paraphrased” or revealed any information regarding the actual time(s) Mr. Wilds alleges this activity occurred.

Gutierrez has no idea at this point that Jay will testify that the burial took place long after school was out, because the indictment reads as if the burial happened right after Hae was killed.

On September 24 the State discloses that it will introduce a witness from AT&T wireless, implying the witness will be a “documents representative”—someone who can authenticate the records, but not someone who will testify to the calls in a substantive way. They follow this up on October 8 with a disclosure that the State will call an AT&T expert witness at trial, someone prosecutor Kathleen Murphy and a Baltimore detective took a ride with that day to test cell tower locations. Jay joined them. The cell expert, whose name they disclose the following day, is Abe Waranowitz, a radio frequency (“RF”) engineer with AT&T.

They also disclose a summary of Waranowitz’s oral report. The summary is not accompanied by any written results but is Murphy’s account of the expert’s oral reportings to her. The ambiguity results in a frantic letter by Gutierrez two days later to AT&T attempting to get the information alluded to in the State’s disclosure, namely maps with cell tower sites. This is the first the defense has heard the State will be offering any evidence related to cell tower site locations, and the trial is scheduled for three days later, on October 14.

A motion by Gutierrez to “continue,” that is, delay the trial, is granted by the judge on October 14, and at that point she still doesn’t have a single statement made by Jay, any statements by Jenn, or cell tower location information or maps.

But the day before the new trial date of December 8, Waranowitz faxes Gutierrez a list of the relevant cell tower sites, two maps he prepared, and a spreadsheet of cell tower frequencies, all of which still add up to less than meaningless documentation, given that Gutierrez has no idea what the significance of any of it is.

And just like that, with barely anything to go on, Adnan and his defense team go to trial.

* * *

The first-degree murder trial of the State v. Adnan Syed began on December 8, 1999, in the Baltimore City Circuit Court with the Honorable Judge Williams Quarles presiding.

I wasn’t there. It was a weekday, of course, a Wednesday, and my law school semester was fast coming to a close. Final exams were around the corner.

I spoke to Adnan frequently in the weeks leading up to the trial. He was nervous but trusted Gutierrez. I had yet to meet her, but I had heard all about her and done my share of Internet sleuthing. She had an incredible reputation and, according to Adnan, had offered him a lot of attention and kindness in the past eight months. He could sense that she felt protective of him and it reassured him. She told him, repeatedly, that the State had nothing. The forensic disclosures they had made so far indicated that neither the blood on the T-shirt found in Hae’s car, or the hairs they tested, matched Adnan. They had nothing but Jay.

It wasn’t until the first day of trial, when evidentiary and preliminary motions took place, that the State finally turned over Jay’s police statements from February 28 and March 15, after repeated motions by Gutierrez. Nothing about his March 18 or April 13 meetings was disclosed. The State still didn’t turn over Jenn’s statements, or those of any other witnesses, and challenged Gutierrez’s request for Jay’s statements by arguing (1) there was nothing exculpatory in them and (2) he was a witness and not a co-defendant.

Cell tower location information faxed to Gutierrez.

Gutierrez understood—probably after sitting through the grand jury examination of Bilal, and hearing from Saad and others that the police were asking about religion—that Islam and Adnan’s ethnicity were the foundation of the State’s argument toward motive. And she wanted the court to be aware and take into consideration any jury bias that could taint the proceedings as a result.

Prior to voire dire, in which the jury was selected, Gutierrez says to the judge that “there have been particularly in print, but also in TV and radio media nonstop for the last eight weeks or so since the coup in Pakistan, news events regarding that coup and the political implications for peace in that area and others and specifically related to this country.” Judge Quarles asks her if she is “going for … basically, Arab, Islamic bias?” She says yes.

The judge assures her that he will attempt to elicit any such bias from the jury pool and then asks this follow-up, “I understand the importance of Islam in the case, does her [Hae’s] Catholicism or lack thereof play any part in the case?”

Even before opening arguments, the court is already aware that Adnan’s religion plays a role in this case, though it’s not clear how this information is known, since charging documents have no such information. Either the judge has in hand the bail hearing transcript, or the grand jury testimony, or has simply heard it through the legal grapevine. Regardless, it is now publicly known that this is not a run-of-the-mill dating violence case.

Jury selection begins on the 8th and runs into the next day, when both the State and defense also give their opening statements. This is the first time Gutierrez and Adnan get to hear exactly what the State will be alleging in the particulars of the crime. The State lays out its case:

[Jay] gets a page to meet the Defendant at Best Buy. He meets the Defendant there. The Defendant has Hae Min Lee’s car and says look I did it, pops the trunk, there’s the body of Hae Lee. At that point Jay Wilds is totally shocked and stays in a state of shock. […] You’re going to see another exhibit which is a map of cell sites and how they correspond to the City, and you’re going to see. […] That both of those calls were made from the [Leakin] Park cell site. And you’re going to hear how the body was buried and recovered from [Leakin] Park.

It is a short, methodical, precise opening. Gutierrez, however, opens with a long, rambling (and sometimes inaccurate) lecture on Pakistanis and Islam:

[Adnan] happens to have been born of Pakistani extraction. His parents are American citizens by choice. For those of you—you may or may not know some of the history of Pakistan, which is a country that was formed in the Arab world in the tip of the land mass called Asia. (Indiscernible) is in the northwest corner of what was once India. […] And Pakistan was formed because, within India, hundreds of years of settlements from Hindus and Moslems could not get along and subsequently Pakistan broke off. [… A]t some point, many Pakistanis—the bulk of whom were Moslem—many of them came to this country to seek peace and economic opportunity. […] They brought with them their religion. […] And they brought their customs and way of life.[…] And they formed communities as Moslems and as Pakistanis. […] On the rest of the world, Islam is a major religious force for people in many different countries—Arabic, Asian—but all over the world Moslems live. It is a monophystic (phonetically) meaning they believe in a single god and they believe in a way of life. […] They operate on a different calendar year. […] which doesn’t recognize—other than as a dividing point—the birth of Christ that one the basis of most Christian calendars. And in the Islamic calendar, which runs approximately 12 months—but on a different system—there is one month that the Islamic calendar use as a sacred month of renewal and discipline, and a call to the faithful Islamic to come together and do certain things to remind them of the discipline of their faith […] in addition to the house of worship where the faithful of Islam gather—and particularly during Ramadan—five times a day to pray according to the book of their religion—the [Koran]—to pray and open their souls and their hearts to the discipline of the words of Mohammed. […] The hope of the mosque in building the school is to prevent the impact on their children in what they view as the outside world, and every year they add a grade so that there is a fundamental Islamic school system where they can keep their children away from the evilness of a world that they interact with but they know does violence (inaudible). That is a world that Adnan Syed came from. And that friction certainly caused him friction. Now Adnan—and you will learn this from everyone—his friends, from the teacher, from the friends of Hae Lee herself. Adnan was a young man who was liked by everyone. He was a leader. He was a scholar. He was an athlete. […] And he viewed himself […] as a strict, fundamental Moslem, as a good Moslem.

In many ways, spending so much time speaking about Islam and Pakistan, Gutierrez has not only confused a jury that probably had little knowledge and is now getting all sorts of conflated, unconnected facts thrown at them, but she is also confirming the role of Islam in the case and “otherizing” Adnan far better than even the State can do. Not to mention that much of her opening is unrelated and irrelevant to the crime itself and has little discernible organization. Her best bet was to open with the facts of January 13, 1999, tell the jury her witnesses will show Adnan was at school when the State says Hae was killed, and emphasize that the State’s case is based on bias and bigotry. Instead, she inadvertently legitimizes their theory.

Gutierrez goes on for fourteen transcribed pages before the judge asks her how long she’ll be. She responds that she needs another fifteen, twenty minutes. Half an hour later, it takes a five-minute warning by Quarles to finally shut her down.

The next day, the State begins to put on its witnesses, starting with Hae’s brother, Young Lee.

Lee testifies to the events of January 13, including the phone calls he made, Adnan’s and his sister’s relationship, and the T-shirt with bloodstains found in Hae’s car. Lee states that the shirt is a rag she kept to clean up around the car. Using Lee’s testimony as a foundation, the State enters Adnan’s phone records, a prom picture of Hae, and her diary into evidence and ends their examination. Gutierrez does a short cross-examination in which she asks about Lee’s knowledge of Hae’s new boyfriend, Don, and ends by asking if Hae hid her relationship with Adnan from her parents. Lee responds, “She did.”

The State’s next witness is Nisha Tanna, whom Adnan had met nearly a year prior at a New Year’s Eve party on December 31, 1998. Nisha was asked specifically about a call placed to her phone from Adnan’s cell on January 13. The call was made at 3:32 p.m. and lasted two minutes and twenty-two seconds. But before showing her the call records, Urick asks her about the one time she ever spoke to Jay Wilds.

Nisha testifies, in response to whether she was sure she spoke to Jay on January 13, “It’s a little hard to recall but I remember Jay invited [Adnan] over to a video store that he worked at and he basically, well Adnan walked in with the cell phone and then he said, like he told me to speak with Jay and I was like okay, because Jay wanted to say hi, so I said hi to Jay and that’s all I really recall.”

On cross Gutierrez has Nisha reaffirm that she isn’t sure what date she spoke to Jay and that it happened at a video store.

Nisha’s testimony adds one more piece of the narrative puzzle of the State’s case—by using that cell phone call, they are going to corroborate that Adnan and Jay were together that afternoon.

The rest of this first day of testimony includes Officer Scott Adcock, who testifies about his investigation the day Hae went missing, and then Sergeant Kevin Forrester, who testifies to the condition of the windshield wiper/selector switch in Hae’s car when it was found. Forrester had taken a video of the car on March 16, 1999, to show that the windshield wiper was hanging limp from the steering column. He also testifies to where the car was found, pointing it out on a map for Urick.

Gutierrez has exactly one question for the sergeant: “Detective Sergeant, the person who directed you to where the car was found was Jay Wilds?” Forrester responds yes.

Salvatore Bianca, a criminalist in the trace labs unit of the Baltimore City Police, testifies next. Bianca had tested the T-shirt found in the car and under Urick’s direct examination, admits that it is possible that it is not just blood but also mucous staining the shirt. He testifies that the blood on the shirt comes from Hae and no one else and that two fibers found on her body did not come from her clothing.

On cross Gutierrez elicits from Bianca that there was no semen found on any of the samples he took, and also that the comparisons done of the blood stains were limited to two suspects: Adnan and Jay. As Gutierrez tries to establish that testing was unduly delayed, Urick responds that the defense was on notice of the samples and could have requested testing themselves but didn’t. This doesn’t sit well with Gutierrez, who mutters her disapproval out of the judge’s hearing range.

Prosecutor Kathleen Murphy hears it though, and raises an objection: “Judge, I’m going to object to defense counsel calling my co-counsel an asshole at the trial table that she did just a moment ago.”

The last witness called that day is Romano Thomas, assistant supervisor of the Mobile Crime Lab Unit of the BPD. Thomas had been part of the team that responded to both the burial site and the location where the car was recovered, and he testifies as to how evidence was collected from both crime scenes. In particular Thomas testifies about how the fingerprints and palm print were collected from the floral paper, insurance card, and map book. He also testifies about the note found in Hae’s car, in her handwriting and addressed to Don that he reads for the jury, “Hey cutie sorry I can’t stay I have to go to a wrestling match at Randallstown High, but I promise to page you as soon as I get home. K? Till then take care and drive safely. Always, Hae. PS, the interview went well and I promise to tape it so you can see me as many and as often as you want.”

Gutierrez has no questions on cross and the day’s proceedings end. The next day further testimony is presented about the fingerprints by Sharon Talmadge from the latent print unit of the BPD. Talmadge essentially affirms Thomas’s testimony but adds one very important fact: that sixteen of the fingerprints taken from Hae’s car returned negative results. They didn’t match Hae, Jay, or Adnan, or anyone in their database.

Gutierrez, on cross, makes the point that Talmadge was only given two suspect prints from which to compare the recovered prints, and wasn’t even provided the prints of Alonzo Sellers, the neighborhood streaker. Showing the myopic focus of the investigation is her goal.

“Did there come a time when the fingerprints and the palm prints of a person by the name of Alonzo Sellers were submitted to you?”

“No, they were not.”

“And did you, Ms. Talmadge, put any restrictions on the police department as to how many names—of how many suspects they could submit evidence against which you were to compare any evidence that you could recover?”

“No.”

“If they had submitted to you a list of ten names would you have conducted the very same thorough analysis that you did as you’ve described to us today?”

“Yes.”

“If they had submitted twenty names, would you have done the same thing?”

“Yes.”

Day three of the trial opens with testimony by Emmanuel Obot, a crime lab technician with BPD, who was present during the search of Adnan’s home. Obot identifies a picture of the book pulled from Adnan’s room that held the cards, letters, and pictures of and from Hae, including the note with the “I’m going to kill” line written across the top. Gutierrez makes an attempt to imply on cross that the book, out of an entire bookshelf, was specifically pointed out by Ritz to investigate, trying to raise suspicion about the fortunate coincidence of this discovery.

Detective O’Shea next takes the stand and testifies, most significantly, about the ride that Adnan was supposed to have gotten from Hae after school but then denied when later interviewed. Gutierrez does a solid cross-examination then, raising the facts that Hae was seen by someone other than Adnan at school at 3:00 p.m., that Adnan was likely at track practice, and that Adnan himself had asked to meet with O’Shea to answer questions willingly.

The State then calls witnesses connected to Woodlawn High—the principal Lynette Woodley, nurse Sharon Watts, athletic trainer Inez Butler, and students Krista Meyers and Debbie Warren.

Woodley testifies to events on the night of the homecoming dance when Adnan’s parents showed up at school. She states that she saw his parents talking to Hae and intervened, telling her to return to the dance, and that she later asked her if she really wanted to be involved in a relationship where it was creating family problems.

Watts gives more testimony that raises questions about Adnan and the context of his relationship with Hae. She recounts the day it was announced in school that Hae had been found murdered.

“He appeared shocked. His eyes were big. He was mute. He wasn’t talking. He wasn’t crying. He was just absolutely stone still … As soon as I touched Adnan and started to walk him into the health suite the look changed. The eyes weren’t so big. His posture wasn’t so erect. He walked easily. He didn’t need any leading … And just with that alone, his supposedly catatonic appearance changed … My opinion was that this was a very contrived emotion—very, very rehearsed—very insincere.”

Gutierrez doesn’t do much to counter this assessment other than draw Watts to testify that she hadn’t seen Adnan and Hae together other than once, and that she had no experience with Adnan—she had never examined him before. On redirect, Urick asks one question: “What is a pathological liar?” Guterriez objects, and the court sustains the objection.

Krista Meyers and Debbie Warren primarily testify about Adnan and Hae’s relationship, the impact of the family pressure on it, how they both took their eventual breakup, and how Adnan reacted at the news of Hae’s death. Urick has Krista identify the writing on the “I’m going to kill” note as Adnan’s without actually reading it out loud in order to enter it into evidence—he’s going to “publish” it with another witness. Urick also asks her about the conversation she had with Adnan the morning of the 13th and she responds, “I recall him mentioning … that Hae was supposed to pick him—pick up his car that afternoon from school because he didn’t have it for whatever reason. Either because it was in the shop or his brother had it, I’m not sure which.”

Gutierrez does nothing to address this potential ride but has Krista testify about the fact that Hae and Adnan were still close after breaking up, still friends, and that likewise Adnan and Stephanie McPherson were also very close friends.

Having established Debbie as a friend of Hae’s who knew about the problems of their relationship, Urick has Debbie read a series of passages from Hae’s diary in which she discusses her concerns about Adnan’s religion, doubts about their future, and about falling for someone new, Don. Debbie is also asked to read for the jury the exchange between Adnan and Aisha Pittman on the back of Hae’s note to him, and she concludes her testimony in dramatic fashion by reading the words “I’m going to kill.” Gutierrez continuously objects to all of it, from the diary passages to the note, and her objections are continuously overruled.

On cross, Gutierrez gets to the most important point she needs to elicit from Debbie, that she told detectives she saw Adnan in school by the guidance counselor’s office around 2:45 p.m. on January 13.

Gutierrez reads from Debbie’s police statement: “‘And I’m positive just about then I saw Adnan that day before he went to practice. I spoke to him and a couple other kids. And then that was very short—that wasn’t a long period of time that we did that.’ And then probably about 2:45 you left. Do you remember telling them (police) that?”

“Yes.”

One last important witness takes the stand on this day: Donald Clinedinst.

Don testifies to having seen Adnan before he and Hae began dating because Adnan would occasionally swing by the store, and after they began dating, he saw him one more time. Hae had a small accident in the snow and called Adnan to take a look at her car, an incident Hae writes about in her diary. A discrepancy here, though, is that she indicates this happened in December, before she and Don began dating, and he testifies it happened after they began dating, which would have to have been in January.

Urick offers Don’s employment records into evidence through his testimony, helping to establish that he was at work until 6:00 p.m. on the day Hae disappeared.

Gutierrez asks Don to describe Adnan and his relationship with Hae after they broke up—that they were still friends, and there was no hostility.

The next day, Tuesday, December 14, the State calls more witnesses to testify about the forensics, including the medical examiner, Dr. Margarita Korrell, who testifies about the autopsy and manner of death. She offers evidence that led her to conclude Hae was strangled in a homicide: eye hemorrhaging and a broken hyoid bone. She also testifies about the condition of the body and how it conforms to the theory that Hae was killed on January 13, 1999. The State then brings up evidence that shows Hae was not just strangled, but that she was hit viciously beforehand, asking the doctor to refer to the portion of her report that refers to bruises on Hae’s head.

Dr. Korrell explains, “These are bruises that are in the right occipital and right temporalis muscle … (T)hey are under the skin, subfilial is on the surface of the bone and into the muscle of the right temple. And they only occur when the heart is still pumping.”

Gutierrez is able, on cross, to get the pathologist to admit that there is no way to pinpoint the time of death. She also gets her to admit that there was no sign of external bleeding on the body. Lastly, under cross Korrell testifies that there was no sign of semen in any of the swabs taken from Hae’s body.

Next on the stand is Melissa Stangroom, a forensic chemist with the Maryland State Police Crime Lab. Stangroom was in charge of the DNA testing on the bloodstained shirt. Her conclusion after testing was that while Adnan and Jay could be ruled out as the source of the blood, Hae could not. This allowed for the possibility of other suspects. Gutierrez pounced on this, asking Stangroom about how many samples she was asked to compare the blood to—only three, making a point to show how narrow the State’s investigation was.

The prosecution also calls Woodlawn French teacher Hope Schab, who quickly establishes herself as someone deeply suspicious of Adnan’s behavior. She testifies about a time when Adnan was waiting for Hae in her classroom and Hae called the room phone, pretending to be a teacher, and asked Schab not to tell him where she was because they had a fight. She also testifies that she has been coordinating questioning with teachers and students, and indeed was even investigating Adnan herself, because Detective O’Shea had asked her to. She was asking around about his sex life, and Adnan asked her to put a stop to it, saying, “Are you asking questions about me, because, you know, my parents don’t know everything that goes on in my life, and I would appreciate it if you would, you know, not ask questions about me.”

The State then calls Yaser Ali, Adnan’s friend of many years who also attended his mosque. Yaser’s number shows up twice on Adnan’s cell phone on January 13, but Urick also wants him to testify about the do’s and don’ts of being a Muslim. Gutierrez isn’t having it, objecting that this teenager is no expert on Islam, and the judge calls them both to the bench to make their points.

Urick argues that Yaser’s testimony regarding the requirements of Islam are important because, “This defendant was leading a double life. He was leading one life that his parents’ religion wanted him to lead. He was leading a hidden or illicit life that caused him to lie to many people to create different personas, different fronts for different people.”

Gutierrez renews her objection, saying that nothing Urick was exploring with this witness had any relevance to the day the murder was committed.

The judge sides with Gutierrez, stating, “I have some difficultly in exploring any witness’s religious beliefs sort of generally … I think we raise needless due process considerations if you’re going to do generally an exploration of his adherence to his religious beliefs,” and telling Urick that he will have made his point if he gets to whether Adnan and Hae’s relationship was frowned upon in Islam.

Having been duly guided, Urick returns to examine Yaser further about what Islam has to say about dating and premarital sex.

Gutierrez is successful on cross in getting Yaser to testify that this “double-life” angle Urick is getting at actually applies to all the young Muslim men at the mosque who are dating. She ends with a long line of questioning on Ramadan, the involvement of Muslims at the mosque in this month, and the honor of leading prayers.

The last witness to testify before the State’s key witness is a young woman named Kristina (Christina in trial documents) Vinson.

Adnan does not really know Vinson except as a friend of Jay and Jenn. But her testimony is about to place him with Jay in her house at a crucial time on January 13, right before he is supposed to have buried Hae around 7:00 p.m. It’s the first time he’s going to hear this part of the State’s case, and he’s perplexed because while he remembers once having swung by her apartment with Jay, he is almost certain it wasn’t on that night. But he could be wrong—after breaking his fast that night he had gotten high and, in all honesty, what happened after smoking pot wasn’t exactly clear for him.

Vinson, however, recalls January 13 as the night that Jay showed up with someone she had never met before at her apartment between 5:30 and 6:00 p.m. while she was home with her boyfriend, Jeff Johnson. She had been at a conference all day and had gotten home shortly before they arrived.

She says that Adnan was out of it, high as a kite, didn’t say a word, just came in and slumped over on some pillows on the floor. She tried to make small talk with Jay, whom she knew through Jenn, and he told her that they were coming from a video store and were waiting to be picked up. The conversation got confused, she said, so she dropped it. At some point, Adnan apparently popped up and asked, “How do you get rid of a high?” and she told him he had to wait it out.

She describes a call to Adnan’s cell phone then, and his responses along the lines of “What am I going to do? They’re going to come talk to me,” shortly after which he jumped up and just walked out of her apartment. Jay, she says, is a bit taken aback, but then gets up and follows him, leaving behind his hat and cigarettes.

Jay returned later that night, she testifies, this time with Jenn, around 9:30 or 10:00, and they were “acting really funny, really strange.” But no amount of questioning got her any answers about what was going on, so she dropped it.

An important part of Vinson’s testimony is how she helps the State create a visual timeline of events for the jury. A large, blown-up map in the courtroom becomes the guide and, along with Adnan’s cell records, helps the State pinpoint which call corresponds to Vinson’s story, and which cell tower site on the map corresponds to her house. Everything fits.

On cross, Gutierrez points out that Vinson first became aware of the crime when she took her good friend Jenn Pusateri to the police station on March 9, 1999. On that same day she had also given statements to the police, which differed a bit from her testimony. Gutierrez asks her about the discrepancy, noting that Vinson had earlier told detectives that Jay and Adnan had arrived at her home between 5:15 and 6:00 p.m. and stayed 35 to 45 minutes. She begins to question her about the description she gave the police about Adnan being Indian or mixed-race, but misses something crucial—that in her police interview she describes Adnan as five feet seven. Adnan, however, was around six feet tall at the time of his arrest. She does point out that Jay never introduced Adnan to her, implying that she may not know if it was Adnan or not—though at this point Vinson has already identified Adnan in the courtroom.

After an exhaustive, repetitive cross, going over Vinson’s testimony and all manner of collateral subjects like Vinson’s favorite television show, Judge Quarles finally says, “In an effort to finish this millennium, Ms. Gutierrez, can we get back to the points at issue in this case?”

* * *

Jay Wilds is sworn in on the afternoon of December 14, the fifth day of the trial. Urick wants to get one thing out of the way immediately, the plea agreement. He asks Jay, in his own words, to describe it. And Jay does, in a single sentence: “The plea was just that, basically a sentence cap that I can only be sentenced to the maximum—sentencing for my part as long as I told the truth and nothing but the truth.”

Urick quickly gets Jay to the night of January 12, when Adnan first got his cell phone and, according to the State’s theory, called Jay to set up Hae’s murder.

But instead of telling the jury what the State said he would, in response to Urick’s question regarding what Adnan told him when he called him on the night of the 12th, Jay responds, “He just asked me would I like to join him. He asked me—asked me what I’d been doing. The next day was my girlfriend’s birthday, the 13th. Her birthday follows mine. I told him I was going to the mall and shop and he told me he’d give me a lift.”

He goes on to testify that they later went to the mall, where Adnan called Hae “that bitch” and said he was going to kill her, but that Jay “didn’t take in the text of the conversation for what it was.” He says Adnan then said, “If I let you hold my car, can you pick me up later?”

This is in contradiction to his previous police statements where he stated that Adnan called him the night before to request his help in the crime, having planned this all out before, premeditated.

Jay says he has Adnan’s car until Adnan calls him to come to Best Buy, where he shows him Hae in the trunk of her car. He describes not being able to see her face, because she’s facedown, but knowing it was her anyway. He says she’s not wearing shoes, and he notes that she is “kind of blue.”

How Jay manages to see her skin color when she is fully clothed, wearing pantyhose, and lying facedown is a question I wish Gutierrez had asked, but she didn’t.

Jay describes leaving the car at the I-70 Park-n-Ride and then going to pick up weed at his friend Patrick’s house. Gone from the story is Patapsco Park. He says he then leaves Adnan at school for track practice and goes to Vinson’s house, a visit she never described in her testimony. After a bit he goes back to pick up Adnan and then again returns to Vinson’s home. He describes a series of calls to Adnan’s phone that Vinson, again, never testified to.

He says Adnan received a call from Hae’s parents, then another call, again, maybe from her family, then a third call from a police officer.

With more such inconsistencies, Jay continues his narration of their trek to Leakin Park where he helped dig a grave and bury Hae. During the digging, he says, a call came in to Adnan’s phone. He answered and said, “he’s busy,” and hung up.

He describes a complicated dance of the cars where he and Adnan go back and forth, up and down a hilly road that intersects Franklintown Road. First they both park at the top of the hill. Then Adnan takes Hae’s car with her body down by the burial site as Jay waits in Adnan’s car at the top of the road. A while later, he says, Adnan returns with her empty car and orders Jay to come back to the burial site, where Hae is lying facedown, to help him cover her up.

Jay moves through the timeline, describing ditching Hae’s car in a parking lot between a bunch of houses, and then Adnan dumping some of her things in a dumpster, and finally Jenn picking him up in front of the Westview Mall, or his house—he can’t recall anymore.

Urick then calls his attention to the cell records, pointing to different incoming and outgoing calls, trying to match Jay’s recollection with Jenn’s and Nisha’s.

Knowing his prior statements have all kinds of contradictions, Urick attempts to stave off Gutierrez by broaching the subject head-on. He asks Jay why he changed his story about where Adnan popped the trunk and showed him the body from Edmonson Avenue to Best Buy.

Jay responds, “Really there was no reason. I just felt more comfortable if the cops had returned me to a place I feel comfortable in.”

While the answer is a bit cryptic, it seems to be suggesting that Jay changed his statement because initially the police had told him to make the trunk pop at Edmonson. Urick, of course, doesn’t follow that up for any clarification.

Urick then asks why Jay didn’t mention meeting up with Jenn or saying anything to her in his first statement when he did in his second statement.

Jay states, “I didn’t want her to have to be questioned by the police.”

He seems to be forgetting that according to the State’s official version of events, the police only came to him after Jenn had already given them a detailed statement, with a lawyer present, regarding her involvement.

Nonetheless, Jay manages a number of convoluted responses as to why he followed Adnan’s orders (scared he would be turned in for dealing weed and because Adnan threatened Stephanie) and the State finally rests.

Instead of beginning her cross-examination, Gutierrez asks for an overnight recess to review Jay’s statements and taped interviews. In doing so she loses a valuable opportunity to immediately press Jay on these responses.

On December 15, the last day of the trial, Gutierrez cross-examines Jay.

One of her first punches misses completely when she asks if, on January 13, Jay was already working at the porn video shop and he responds in the affirmative. That’s completely untrue, however, and Gutierrez has the interview of Jay’s employer Sis noting that he didn’t start working there until the very end of the month. But she moves on, missing the chance to show that the call Nisha Tanna remembers in all likelihood didn’t happen until a few weeks after Hae disappeared.

She spends a considerable amount of time painting a picture of the social order at Woodlawn, and how Jay wasn’t part of the group of gifted and talented students that his girlfriend, Adnan, and Hae were part of—the Magnet Program. She then spends as much time drawing out the fact that Jay was, for much of the past few years, a drug dealer, pointing out that while Stephanie is now at college, Jay isn’t. Gutierrez’s strategy seems to be to show Jay’s character and his motive for wanting to frame Adnan—out of jealousy for the kind of lives Magnet School kids were going to lead versus the kind of life Jay had.

She notes that Jay is always borrowing other people’s cars, getting him to admit that he borrowed cars from his friends Laura Strata, Jenn Pusateri, and Chris Baskerville as well as his girlfriend Stephanie.

Gutierrez’s cross is long, and exhausting. She repeatedly goes over many of the same things, Jay’s drug dealing specifically, until the judge can’t take it anymore and says, “Ms. Gutierrez, I’m trying to get this finished again by Christmas. You’ve used an hour. Perhaps we can be more pointed in the cross-examination. It might be helpful to all of us.”

Gutierrez continues unfazed, though. She jumps from when Jay met with detectives, to how many people he dealt drugs to, to how and when he learned Hae’s body was found. Every so often Jay would say something incredibly odd, for example, when Gutierrez asked if he knew that Hae’s body had been discovered inside Leakin Park when he was interviewed by police on February 28.

Jay answers, “That’s where it turned out to be, yes.”

Jay’s cross-examination goes on for another few hours before Gutierrez finally rests and the State starts to redirect. They are just getting started when an astonishing exchange takes place. Urick attempts to present State’s Exhibit 31, cell phone records for January 12–14, to the jury. Judge Quarles asks Gutierrez if she has seen the records and she says no.

Urick counters, saying she has seen it and that it was entered into evidence by stipulation, meaning by the consent of both parties.

Gutierrez again says she has not seen the exhibit Urick is referring to, even when the judge also reminds her she agreed to the exhibit being entered into evidence.

The judge then calls both attorneys to the bench to figure out what is going on. Gutierrez had stipulated to Exhibit 31, meaning she did not challenge its admission. She absolutely knew about the records, yet here she was telling the court that she hadn’t seen them.

Judge Quarles admonishes her, saying, “Ms. Gutierrez, if you are going to stand there and lie to the jury about something you agreed to come in, I’m not going to permit you to do that.”

Gutierrez gets belligerent.

It is impossible to understand how an attorney with decades of criminal defense experience (1) stipulated to the admission of documents she had not looked at and (2) could tell a judge with a straight face that she stipulated to admitting documents without looking at them because she “did not care.”

Gutierrez explains to the court that the documents “didn’t concern me on any other date,” getting louder as the judge asks her twice to “please be quiet.”

She responds, “It’s very hard to be quiet when a court is accusing me of lying.”

The white noise machine is on the entire time to prevent the court from hearing this exchange, but it didn’t work all that well.

Jay’s redirect continues as Urick asks him about the significance of Best Buy to Adnan and Hae’s relationship—Jay responds that according to Adnan, they had sex there. Urick then tries to establish the importance of the map book in Hae’s car, which had a page torn from it, the page that happened to include Leakin Park. He asks Jay if he knows, as Adnan is driving Hae’s car and he is following, how Adnan is navigating. Jay says no.

Gutierrez gets a chance at recross and takes Jay back to this issue, asking Jay about following Adnan all around the city before finally making it to Leakin Park. Jay agrees that this is indeed what happened. Gutierrez lands her point that the long, uncertain route Adnan took there must show he hadn’t decided on the location beforehand.

Jay is finally released from the stand, even though Urick wants to re-redirect, but is cut off by the judge.

Dr. William Rodriguez of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology is next called to testify about examining the burial site.

He describes the location and condition of Hae’s body as follows:

We observed initially that the body was placed in a position near a very large log or tree that had been downed. It was in very close proximity to this and that the body was partially covered with dirt. It was very shallow. However there were three components of the body that were partially exposed; that being some portions of the hair, a portion of the hip, and a foot and knee area. And in examining those, it was obvious that these had been exposed as a result of post-mortem animal activity; that is, animals coming to feed or that are attracted to the remains, and through their activity, they basically had teased out the hair from underneath the ground and also had uncovered dirt and removed it from areas that covered portions of the body.

He describes small scratch marks and mud prints of small animals that had uncovered portions of the body. This would seem to contradict the autopsy report that shows no evidence of animal activity on her body, which is also a bit of a mystery, given that in most such circumstances, soft fleshy parts of a body so exposed (such as the ears, fingers, nose) are often quickly nibbled on by foraging animals.

Rodriguez then explains how the body was disinterred, carefully, using small trowels and brushes, and discovering two fluorescent fibers—one orange, on top of the body, and another bright blue, underneath the body.

Urick asks whether the condition of Hae’s body was consistent with her having been killed on January 13, 1999. Rodriguez says yes.

On cross, Rodriguez is asked by Gutierrez about the condition of the park itself and the ease or difficulty of reaching the burial site, agreeing with her when she says the terrain is hard to get through to take a body and that there was no path, other than the ones the officers ended up creating, leading from the road to the body.

Gutierrez is attempting here to show the unlikelihood of Sellers traipsing back to the burial site to take a leak, and she’s done a good job.

As she’s wrapping up her cross, she notices a juror is trying to say something to the judge and calls the clerk’s attention to it. Rodriguez finishes his testimony and they take a short break.

Once court reconvenes, Gutierrez tells the judge that she has just been told that their exchange, in which she was called a liar by the judge, was heard over the white noise machine by colleagues Chris Flohr and Doug Colbert as well as others. She moves for a mistrial based on the fact that the court has attacked the credibility of Adnan’s attorney.

Judge Quarles already knows what happened, because the juror who was trying to get his attention sent him a note, reading, “In view of the fact that you’ve determined that Ms. Gutierrez is a liar, will she be removed? Will we start over?”

The judge immediately grants Gutierrez’s motion for a mistrial, and Adnan’s trial for first-degree murder ends on the sixth day.

* * *

Doug Colbert was still deeply invested in the case even though he no longer represented Adnan. On the afternoon of December 15, after the heated exchange between Gutierrez and the judge, he had to leave. But he returned as soon as he could, only to find the proceedings had abruptly ended.

Colbert later submitted an affidavit to assist with yet another attempt to grant Adnan bail as he awaited a new trial, now scheduled for January 21, 2000. In it he states that as the jury filed out he spoke to most of them and they advised that had the trial resumed, they would have acquitted Adnan based on the State’s case so far. Colbert notes Adnan’s stellar record and inexperience with the criminal justice system and that his life could be “needlessly destroyed by wrongful incarceration or conviction.” He cites the hardship Adnan is experiencing while incarcerated and requests the court grant Adnan’s bail as he awaits trial.

But like the past three applications, this too was denied.

Adnan would remain incarcerated pending another trial, which, thankfully, would begin soon.

Though denied bail, at least the defense, Adnan, and his family now knew this: despite many rambling moments by Gutierrez, and not yet having even put on the defense case, jurors were still likely to acquit. Maybe all this time Gutierrez had been right—it was the State’s job to prove their case, and they couldn’t. The evidence they presented would not pass the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard.

But Adnan was still worried, and considering a plea deal. He knew the State hadn’t yet presented its full case when the mistrial was called, and he saw how effective they were in using the only real evidence in the case, the cell phone records, in corroborating Jay’s timeline. He worried about whether another jury would find Nisha’s testimony about the cell phone call damning, and if the State would return with an even stronger presentation. After all, it wasn’t just the defense that got a preview at the first trial, the State also got to do a trial run with Jay Wilds.

Adnan sat through Jay’s testimony mostly stunned. None of it was true, but he had to sit there and listen to the lies, conscious of the eyes and attention of the courtroom of people behind him. He pretended to scribble on a legal pad, trying to hide his mortification.

Now he’d have to do it all over again.

Adnan asked Gutierrez again to ask the State if they were offering a plea, and again she returned with a negative.

So he waited, trusting Gutierrez would be even better prepared for the next go.

The second trial was presided over by the Honorable Wanda Heard of the Baltimore Circuit Court. It began in earnest with opening statements on January 27, 2000.

This time Urick had learned his lesson. The jurors had told him his witness wasn’t credible. Urick was going to turn Jay’s lack of credibility on its head.

His opening struck an entirely new tone, but he didn’t forget to set up Adnan as the slighted young Muslim man.

“This relationship caused problems. The defendant is of Pakistani background, he’s a Muslim. In Islamic culture, people do not date before marriage and they definitely do not have premarital sex. Their family is a very structured event. They’re not supposed to date. They’re only supposed to marry and engage in activities after they marry. So he was breaking the cultural expectation of his family and religion to date Ms. Lee.”

He goes on to read passages from her diary that drive home the message that religion was the issue here, focusing on an entry Hae wrote when Adnan had accompanied his father to the Islamic conference in Dallas.

Then he went into the whole explanation of the purpose of the trip to Dallas. He told me that his religion means life to him and he hates it when he sees someone purposely going against it. He tried to remain a faithful Muslim all his life, but he fell in love with me which is a great sin. But he told me that there is no way he’ll ever leave me because he can’t imagine life without me. Then he said one day he would have to choose between me and his religion. […] He said that I shouldn’t feel like I’m pulling him away from his religion but hello, that’s exactly what I’m doing. I don’t know how we’ll live through all this. But this is bad.

But Urick still has to account for Jay, the star witness that the first jury didn’t believe.