And verily, with hardship, comes ease.

Holy Quran 94:6

If there was tremendous hope in the years leading up to the post-conviction appeal, the aftermath of the hearing brought a sense of depression bordering on desperation. A state prosecutor had testified that we had pressured our alibi witness, an absent witness at that, into making statements. What judge would take our word that a witness who refused to show up had written her more-than-decade-old affidavit in good faith?

It was one of the few times in over a decade that I heard a hint of despondency in Adnan’s voice. I think on some level we all knew that the chances of winning the appeal were slim to none, and the prospect of him living the remainder of his years in a supermax facility far from his family were high.

One night about a year after the hearing, in October of 2013, as we still awaited a decision from the court, I flipped through the new shows on Netflix. It was late, the dishes were done, my husband had already retired for the night, and my girls were peacefully conked out. But I couldn’t sleep.

I lay on my sofa, feeling restless, when a familiar name caught my eye as I ran through the titles: West of Memphis.

It was a new documentary, the most recent of four about a case that had long haunted me, and haunted much of the country. In 1994, three teenagers in West Memphis, Arkansas, were tried for the murders of three young boys a year prior. Damien Echols, Jessie Misskelley Jr., and Jason Baldwin were all convicted, with Echols receiving the death sentence. Misskelley was sentenced to life plus twenty years and Baldwin was sentenced to life imprisonment.

The crime was shocking, gruesome. On May 3, 1993, three eight-year-old boys disappeared. The three friends, Michael Moore, Steve Branch, and Christopher Byers, had last been seen riding their bikes in the neighborhood. But as darkness fell and their parents began to look for them, they were nowhere to be found. Three days later, after an extensive police search, their small bodies were discovered naked, mutilated, and bound in a nearby creek.

At the time, in the early 1990s, the country was gripped by the fear of occultism and satanism. There was no daytime talk show host who had not covered the topic, and across the nation law enforcement agencies were being trained in the rise of crimes that might be tied to occultist rituals, such as human and animal sacrifice. In the eyes of the local police, this terrible tragedy immediately had the hallmarks of ritual or cult murder.

The impetus for the focus on a satanic angle came from the confused statements of a local child during a May 6, 1993, interview. The boy had accompanied his mother, Vicki Hutcheson, to the police station, where she was going to be interviewed in connection with the case. The attention of the police turned from mother to son when he began offering information about the case, saying the victims had been killed by Spanish-speaking satanists, though he could not pick out Echols, Misskelley, or Baldwin from photographs.

Armed with the conviction that this crime was tied to satanism—much like in Adnan’s case where the police were convinced the crime was tied to his religion and culture—the police early on focused in on Echols, who was known to be involved in the occult, kept pentagram-inscripted artifacts, and was also familiar to law enforcement for previous petty crimes. The fact that Echols came from an impoverished family and was diagnosed with severe mental illness, including hallucinations and delusions, which led to months spent earlier in a psychiatric hospital, did not factor into the investigation or mitigate the results of a polygraph that indicated deception.

Misskelley, age sixteen at the time, was questioned exhaustively for nearly twelve hours, though less than two of those hours were actually videotaped by the police. In that time, he confessed to the murders and the involvement of Echols and Baldwin. He would later recant that confession, saying he was exhausted, threatened, and manipulated by the police, and also did not understand the entire interrogation, but the Arkansas Supreme Court would uphold the confession as voluntary, despite the fact that Misskelley had a demonstrated IQ of 72, only three points above the range of mild mental retardation.

From Oprah to Geraldo, the media was breathless and giddy, focused on how occultism led to this tragedy, terrifying the parents of kids who liked heavy metal music and wore smudged black eyeliner to match their brooding dispositions.

A precursor to the media circus that the O. J. Simpson murder trial would become later that year, the West Memphis Three trials were no less of a news frenzy.

But subsequent appeals gave enough time for the release of documentaries in 1996 and 2000, and the publication of the book Devil’s Knot in 2002. The publicity, which cast doubt on the convictions, spurred a national movement to exonerate the three young men.

Over the following decade the case would be publicly dismantled. Hutcheson recanted her testimony, citing police coercion that forced her to lie or face losing custody of her son; juror misconduct came to light; and most compelling, DNA testing on a hair found in the shoelace used to tie up little Stevie Branch’s feet came back negative for all three defendants. Instead, it matched Stevie’s stepfather, Terry Hobbs, whose whereabouts were unaccounted for in the hours the boys went missing.

The defense team strategically made the DNA findings public and laid the groundwork to move for a new trial. After the same trial judge refused to reopen the case, it moved to the Arkansas Supreme Court.

Finally, in November 2010 the Arkansas Supreme Court granted all three defendants new trials based on the DNA testing results and juror misconduct. But the State opted not to retry the case, and instead offered Alford pleas to Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley.

In August 2011 the three were released, having accepted the plea—a convoluted legal construction that requires them to accept guilt for the crime, but also maintain their innocence. Three young men lost eighteen years of their lives, but as far as the State is concerned, the case is closed. The investigation into the brutal murder of three little boys will not be reopened, and the culprit will remain free.

In 2012, the documentary West of Memphis was released, chronicling the eighteen-year-long battle of these three young men.

* * *

Over the years, as appeals came and went, every so often I’d float the idea to Adnan of taking the case to a journalist. I pointed out that numerous wrongful convictions were revisited and reopened when public scrutiny came to bear on the State. But time and time again, often after arguing, we made the calculation to wait until the post-conviction, when Asia could be presented along with a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel.

That night, when the documentary ended, I made an executive, unilateral decision. I was going to find a journalist to investigate the case. And I wasn’t going to ask anyone’s permission. Adnan’s resignation was increasing and I didn’t want him to make a decision to spare his family public scrutiny at the expense of an independent investigation of the murder.

I rolled off of the sofa and took my place at the laptop on the dining room table. It was very late at night, but this couldn’t wait any longer. I had to move on my impulse immediately and find the right person for the job.

* * *

Imagine a gritty, worn-down crime reporter. A seasoned, cynical, smart-ass skeptic with a face full of worry lines and a trash bin full of liquor bottles. A journalist who cut his or her teeth on the streets of Baltimore, someone who knew all the snitches, the dirty cops, the tough judges. Who had sources and street cred. Who knew how to dig up skeletons buried deep and long ago. Most importantly, a local.

Such a reporter maybe only exists in John Grisham novels, but that’s who I had in mind. It was not remotely close to the one I found.

That night I began looking for a reporter who had actually covered the murder or Adnan’s trial in 1999. The very first person I came across was Sarah Koenig.

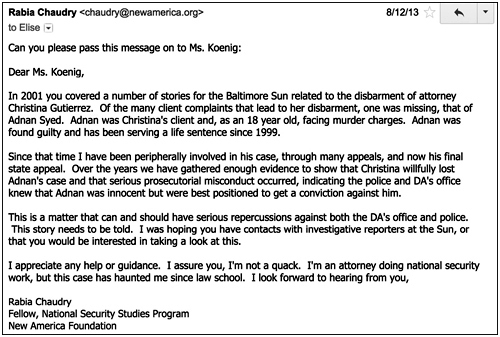

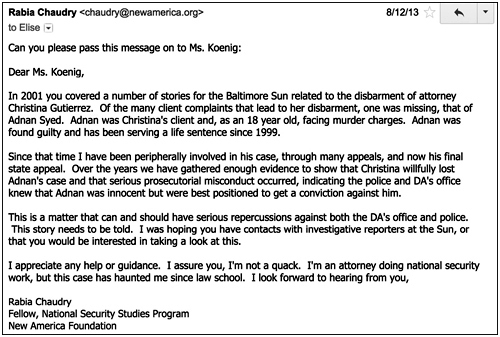

Her name wasn’t familiar, but she had written a piece for the Baltimore Sun in June of 2001 on the disbarment of Gutierrez in the face of overwhelming client complaints.

I thought about it for a second. It wasn’t the kind of coverage I was looking for, but if this woman recalled writing about a lawyer who had botched many cases, maybe she’d be interested in one of those cases.

So I crossed my fingers, said a little prayer, and began my Internet hunt, hoping Sarah was still at the Baltimore Sun. She was not.

She was now a producer at This American Life, a radio show that I was vaguely familiar with. I couldn’t remember if I had actually listened to any of their shows, but I knew they played on public radio.

At that point I really hesitated. A radio producer? And not even for local shows? But I went ahead and shot her an e-mail anyway, and within a day I heard back from her.

I was careful to write to Sarah from my New America Foundation e-mail account. After all, I wanted her to know I wasn’t some kook with a conspiracy theory.

After exchanging many e-mails and a couple of phone calls, we met about ten days later in Baltimore. I wanted to show her not just the documents I held but also the area surrounding the case, so we decided to meet at my little one-room space across the street from Woodlawn High. There was another reason to meet there—to possibly facilitate a meeting between Sarah and Adnan’s family.

That was the tricky part, though. I hadn’t asked Adnan, his attorney, or his family for permission to take the case to the media.

My plan was to forge ahead and ask for forgiveness afterward. I’d get their blessing once I knew Sarah was going to take the story. For now, I had to focus on making my case to Sarah, and I looped in Saad in order to do so.

* * *

Saad and I waited in my little office, where I mostly kept client files of cases I was closing out as I wrapped up my legal practice, visiting a few times a month to check mail and messages.

On my desk was a battered, water-damaged cardboard box. I had kept this box with me for the past fourteen years. In it were two sadly beat-up folders. One contained letters, dozens of letters Adnan had written over the years. The other contained a selection of documents from Adnan’s extensive case files that I thought showed something was deeply wrong with his conviction. I had pulled them years before from the rest of his files, which had been passed around to various appellate lawyers and now rested in the basement of his parents’ home.

The front doorbell played a jingle and then came a tentative “Hello, Rabia?”

I walked out of the room and into the main office reception area to greet Sarah, with Saad close behind me.

I had no idea that Sarah Koenig was a big deal, in a nationally known, award-winning-big-deal kind of way. And nothing about her unassuming appearance, or demeanor, would suggest it either. She was tall and lanky, looking every part the seasoned, pavement-pounding reporter in an informal green cotton blouse, loose woven pants, and a network of black bags slung across her shoulders. Without makeup, her wavy hair on the verge of rebellion, she looked like she was serious about her work without taking herself too seriously. She entered with a broad smile, cautiously friendly, but also slightly awkward as she fumbled with the microphone she held.

I invited her back into my room and we got settled in. She wanted us to start at the beginning. So we did.

I gave her a short summary of the case, of who Adnan was, of our belief in his innocence, and our disbelief in the State’s primary evidence, their dodgy eye witness. Saad chimed in about his friendship with Adnan, their girlfriends and dating habits, and what it was like to be the first-generation kid of immigrant parents. All the while Sarah asked questions and continued taping.

Then I began pulling out the documents, apologizing for their condition. Even some of the individual pages themselves were damaged from having been in the trunk of my car for years.

I showed her a copy of Alonzo Sellers’ polygraph tests, the police report taken from the man who said his daughter was told by Ernest Carter, Jay’s friend, that he had seen a body in the trunk of a car, a vast spreadsheet created to keep track of the details of Jay’s changing police statements, and most importantly, the letters and affidavit from Asia.

After doing my best to convince her that there was a real story here, a wrongful conviction, I broke the news—that I hadn’t yet told (or asked) Adnan about any of this.

But I told her I would, and in the meantime, to help her decide whether to proceed or not, that she should write to Adnan and ask him to add her to his visitor list.

My plan, however, was to get to him before she did. And to do that, I needed his mom on my side.

* * *

I was nervous; I knew this could go badly. Aunty Shamim might be really upset that I betrayed their trust and contacted a journalist without asking permission, and she could refuse to cooperate because she didn’t have the emotional wherewithal to deal with reopening old wounds so publicly.

Either way, I knew I had to be honest about it.

“Adnan never wanted me to go to the media because he thought it would really hurt you. He thinks the community has gone quiet about the issue and if it’s brought back up in the media it will be hard on you and Yusuf. That’s why he’s been hoping that the post-conviction appeal would give him relief and we could avoid the media altogether. But Aunty, the appeal is not going to work.”

Aunty looked confused.

“What do you mean, Adnan doesn’t want me to be hurt?”

I explained it all again and she started crying.

“I don’t care about anything, about the community or what people will say, the only thing that matters is getting him home. Yes, please, let’s do this. I want to talk to the reporter too.”

It took less than five minutes to get her permission. Now it was time to write to Adnan and tell him all about Sarah Koenig.

November 25, 2013

Dear Ms. Koenig,

I hope this finds you well. Thank you for finding the time to respond to my letter. I definitely understand that you must be very busy with your work, and I just want to express how grateful my family and I am for your efforts in trying to shed some new light on my case. Rabia always used to say that a fresh pair of eyes may uncover something that we have overlooked or discover something that may be crucial. And regardless of the outcome, just the fact that you have taken time to read through the voluminous paperwork involved really means the world to us. I don’t think we can thank you enough.

I received your letter on the 19th and I submitted your name (the same day) to be placed on my visiting list. I received the approval today […]

On another note, I really appreciate what you wrote in your letter about deciding to work on the story. I understand that until something that truly exonerates me is uncovered, no one other than me (and the person who really killed Hae) will ever know that I am innocent. And I’m grateful that you wrote that you trust me, and I place that in a very high regard. […]

I’ve been trying to recall any aspects of the case that could use some explanation. I’ve thought of a few things, and if it is alright with you, I wanted to take some time to explain who Jay Wilds was to me, and why I lent him my car that day.

In order to understand my relationship with Jay Wilds, I have to first explain my relationship with Stephanie McPherson (who was Jay’s girlfriend at the time). Stephanie and I met in 6th or 7th grade. We were really sweet on each other, and became good friends. By the end of 8th grade, we had officially became boyfriend and girlfriend. We would hug and kiss in school, write each other love notes etc. I would go to her house and play basketball, and we would make out and stuff in her basement. As you would imagine 2 8th-graders would. This was in 1995.

That summer, we didn’t really see much of each other. She went to some basketball camps, and me and some of my buddies had got some fake I.D.’s. So we started going to clubs, where I was meeting other girls. So we kinda lost touch, until the first day of 9th grade. We talked about our summer vacations, and it was cool. We just decided to be friends, and we were the best of friends up until the day I was arrested. We were kinda more than friends, like she would sit in my lap, and we world sorta make out (I’m talking about in class). We would talk on the phone a lot, and I would still go to her house sometimes. Anyway, in the 9th grade she started dating Jay. Now, I had known Jay in middle school. He was one grade ahead of me. I used to ride bikes and smoke marijuana with some of my friends, and Jay was like a mutual friend. So he wasn’t my friend per se, but he was friends with some of my friends. So that was the extent of our relationship up until he and Stephanie started dating (in the 9th grade—1996).

So, throughout high school, Stephanie and I grew closer. Once we got our driver’s licenses, we would go out together on like, double dates. Sometimes during the evening, usually Jay and I would go smoke some weed. I got to know him a little better, along with Stephanie talking about him to me over the phone.

[…] So now, fast forward to January 13, 1999. That is the day when Hae disappeared. That is also Stephanie’s birthday. About 10am in the morning, I left school that day to go to Jay’s house, to see if he had bought her a birthday present. He said no, so I told him he could drop me off at school and use my car to go to the mall and buy her one. I had already gave her a birthday present in class that morning. I left my cell phone in the car, cause back then you could get suspended from school if you had a beeper or a cell phone on you. So I finished the school day, went to the library after school, and then went to track practice. Afterwards Jay came and picked me up. By this time it was dark, so it had to be around 5:00pm.

Looking back, I always knew that Jay was jealous of my relationship with Stephanie. He would ask me things (when we were smoking weed) like, “Man, would you tell me if you were screwing Steph?” and “She talks to you on the phone more than me.” Particularly around that time period. Stephanie had told me she was gonna break up with Jay when she went off to college. Jay told me, and asked me if I knew about it. I told him that I did, and he wasn’t too happy about that. At our prom (in ’98) I was the prom king and Stephanie was the prom queen. We had a dance together in the middle of everyone, and had our pictures taken for the yearbook. I had bought two copies of the yearbook and gave one to Stephanie, and she told me Jay caught an attitude when she showed it to him.

Prior to my dating Hae, quite a few people in school thought Stephanie and I were involved. Some knew she was dating Jay and still would say that. We had a social studies class each day, and for the first five minutes of class (before the bell rung), she would sit in my lap and we’d be joking and laughing with our friends. We would hug and kiss each other, and in a more-than-friends type of way. This was in my senior year, up until I was arrested. If she didn’t have any money, I would buy her lunch and we’d sit together. Things like that.

My reason for mentioning all this to you, Mrs. Koenig, is that I think it’s pretty relevant. I shared all of this with Ms. Gutierrez, in much more detail. She told me she tried to arrange a meeting with Stephanie and a P.I. but Stephanie’s family (and she) refused to talk. So none of it was mentioned at trial. A few years after I was sentenced, a friend of mine named Krista Meyers (now Krista Remmers) struck up a conversation with Stephanie via e-mail, it was like an online chat, I think. She asked Stephanie why she turned on me and Stephanie’s reply was: He was my best friend, but I never heard from him after he was arrested, so all this stuff must be true.

Which brings me to my next point. When I was initially arrested, each lawyer I came into contact with stressed vehemently “Do not talk to anyone about your case.” They told me that my phone calls were being recorded, my letters were being screened, etc. And so I didn’t. Some people would write me asking me if I committed the crime, but I never wrote back. And over the years, I would come to find out that a lot of people took that as a sign of guilt. […] Now, don’t get me wrong. My family and Rabia’s family on one side, and the whole world on the other, and they are more than enough support for me … But I think a person may look and wonder how could so many people who knew me come to believe I could commit this crime. And I think my lack of denial/communication played a good-sized part in that.

Krista was someone who was really in my corner. She knew Hae and Stephanie, and was a really amazing friend, both before and after I was arrested. She visited me in Jessup several times, but as the years went by, we fell out of touch. Not in a bad way, but just as life goes on. I have no idea if she still believes I’m innocent or not, but I have a feeling that either way, she wouldn’t mind speaking with you. […]

Sorry for this to be so long. Other than at trial, I’ve never really talked to anyone about these things. I’ve certainly never talked to anyone in-depth about Hae and I. I did not know how it would go over with you. I tried to talk to Justin Brown about it and he immediately cut me off and said that none of that mattered at this stage. […] In my heart, I always wonder if things would’ve turned out differently if the jury had heard me speak about Hae and our relationship/friendship. But I guess that’s just wishful thinking … I will say this, I’m thankful you weren’t all “professional” about it like Justin was. Don’t get me wrong, he’s a really sincere lawyer and a really nice guy. But I really had to work up the nerve to talk to him about how I’m innocent, and I never would’ve harmed Hae. I’m about 3 sentences in when he cut me off, “Adnan, listen. I’m your lawyer. None of that stuff matters at this point. We’re working on your Post-conviction petition. That’s what matters.” So while I appreciated his candor, eventually one day I’m gonna tell him he was a real jerk about it …

I hope you have a good holiday. Take care.

Sincerely,

Adnan Syed

* * *

I was hugely relieved when Adnan agreed to hand the case over to a journalist. And it was an even bigger relief when Sarah, having connected with Adnan and others and reviewed enough documents to hook her, announced she was doing the story. In order to move forward, though, she needed the rest of the documents.

I met Sarah at Adnan’s parents’ house. His mom led us down into the small basement to a closet filled with the kinds of boxes that are synonymous with musty legal files. There must have been close to a dozen of them.

I hadn’t seen these files for almost thirteen years. I first helped the family retrieve them from a storage room where Cristina Gutierrez’s case files were being held for her clients to pick up after she died. I then took the files to my parent’s home and went through them. They had to be delivered to his appellate lawyers, though, and I didn’t have much time.

I spent a couple of weeks, speed-reading and pulling the documents that I wanted to copy for myself, the ones that would eventually make it into the box in my car. I then delivered the full set of files back to Adnan’s family and they passed them on to his lawyer. Over the years these boxes had made the rounds between the lawyers and his home, the last round being at Justin Brown’s office, who had returned them a couple of years prior. Adnan’s family had never gone through them.

Sarah started going through the files, and I stood by with a legal pad handy to note the ones she was going to take. After a while we both gave up and realized she needed too many to keep track. She took a few boxes that day, and then returned to get the rest.

During the first couple of months of her investigation, Sarah and I were in constant communication as I tried to get whatever she needed to her, and introduce her to the community and to people who knew Adnan, like his former attorney Chris Flohr.

* * *

Although it’s hard to know exactly what convinced her that this story would be worth her time, and that there was a potential injustice here, her talk with Chris may have been what cinched it. They met at a restaurant shortly after her initial meeting with Saad and me, and she got right down to business.

She asked Chris what the deal was, was this guy really innocent, because she wasn’t about to waste time on the case otherwise.

Chris reassured her that yes, this was a case that needed to be investigated and that he personally always felt Adnan was innocent. In fact, a few years prior Chris had sent Adnan a letter, his first communication with him since he had stopped representing him in 1999. For all these years he hadn’t stopped thinking about Adnan. He knew that the wrong person had been convicted of this crime. The letter he sent explained a new brain-mapping technology that could determine if a person’s mind had certain memories that could only be stored if they had indeed experienced an event. So if Adnan had nothing to do with Hae’s murder, this technology could prove his brain had no such memories stored.

Adnan had sent me the letter, and after doing some research I learned that the technology was so new, it wasn’t yet recognized by any jurisdiction as evidence. Plus, there was no way Justin would be interested in pursuing something that would distract from his PCR petition, especially something untested.

Adnan had written Chris back to thank him, but we never pursued his suggestion. Still, Adnan was deeply grateful that he still remembered him and made the effort to reach out to an old client.

It was early in 2014 when Sarah told me the great news that This American Life would be committing her and other staff full-time to this story and conducting a full investigation. But I still wondered if I had done the right thing.

The problem was that I didn’t know if an episode of This American Life was going to be able to make a dent in the case itself—it would go by like a blip, barely registering on the Baltimore legal system.

So my hope was not that her final product, the story itself, would prompt a public outcry or movement for Adnan’s exoneration. My hope instead was that once she had gone through the documents, understood the weakness of the evidence and conviction, and met Adnan, she would be a reporter on a quest to find the smoking gun that would prove Adnan was innocent. I wanted to use her investigative skills, and her skills at getting people to talk, to uncover evidence that could get us a new appeal. What her story looked like at the end didn’t concern me so much. It was the investigation that mattered.

But my concern remained about This American Life, even as an investigative tool. In a weird way, being such a big, national outlet with no local ties could prove to be its Achilles heel when it came to this case. So I asked her if she would be willing to work with a local reporter. She didn’t respond immediately but a month or two later teamed up with Justin George of the Baltimore Sun to do some of the local work.

Before that, though, she had a breakthrough. But it was not early enough to save the appeal. The judge had made his ruling.

Sarah got the news before I did, but she didn’t share it with me even though we were communicating almost daily. I hadn’t heard from her in a couple of weeks and wondered what was going on. I dismissed it, thinking it was the holidays, but later she would tell me she didn’t want to talk to me until I found out.

The post-conviction appeal was denied on December 30, 2013. When Justin e-mailed me the news, I was devastated, even though I fully expected it.

My eyes stung with the heat of anger and tears as I read the judge’s opinion. The circuit court had dismissed both claims of ineffective assistance of counsel. The judge found that Gutierrez’s failure to ask the State for a plea deal for her seventeen-year-old client did not rise to the level of incompetence, and that there was no guarantee the State would have offered a plea or that Adnan would have taken one, despite the fact that he had taken and passed a polygraph stating he would have.

As far as the court was concerned, Gutierrez didn’t fumble the ball on Asia; rather she had “several reasonable strategic grounds” for not pursuing her as an alibi witness. Most interestingly, the court found that Asia’s letters “did not clearly show [her] potential to provide a reliable alibi.” That the court pointedly noted that Asia’s only statements were through her letters is an indication that her in-person testimony may have changed the judge’s mind.

But then there was the very strange assertion by the judge that Adnan himself contradicted Asia’s statements. He noted that Adnan testified he never left the school campus until after track practice, whereas Asia saw him in the public library. Except (1) Adnan never testified to any such thing and (2) even if he had, the library was for all intents and purposes on the school campus.

Reading the opinion made me feel like the judge heard very little of what actually happened in his courtroom. I was bitterly upset. Didn’t a man’s life mean enough for the court to at least get right what he had testified to?

But I knew much of this was about Urick’s testimony. Any judge who believed that a witness gave written statements under duress by the defendant or his family and friends would likely discount those statements completely. And any judge who heard this from the mouth of a prosecutor, under oath, would believe every word.

In the face of this denial, Justin did the only thing he could. He filed what’s called an Application for Leave to Appeal or an ALA. Essentially this application is an appeal to the higher court, the Court of Special Appeals of Maryland, requesting one more shot at the same post-conviction claims raised earlier. In Maryland, it is granted in only 1.2 percent of cases.

While he filed the ALA, he also notified Adnan that this would probably be the end of his representation. The Court of Special Appeals would summarily deny the ALA and it would be game over. There was nowhere else to take this case.

I dreaded the inevitable call from Adnan.

What do you say?

“I’m so sorry, the one chance you had after waiting for more than a decade is now gone. Sorry that it’s all over.”

I didn’t say anything, I just cried. Adnan’s response to my teary, mumbled, snotty outpouring was to reassure me, as always.

“It’s ok, it’s ok. It’s from Allah. He’s the only Judge that counts. We’ll appeal this. It’s not the end.”

That was the moment I knew it all came down to Sarah. Sarah had to deliver or Adnan would die in prison. The first glimmer of hope that she would came when I got a slightly dazed and dumbfounded call from her.

“Rabia. I spoke to Asia.”

* * *

After numerous attempts to get a hold of Asia—who seemed as unreachable and mythic as a unicorn—Sarah finally got the call she’d been waiting for in mid-January of 2014.

Asia was timid at first, unsure about what Sarah wanted, why this case was coming back to interrupt her life, why there wasn’t closure on it after all these years. Asia explained to Sarah why she didn’t respond to Adnan’s attorney’s repeated attempts to solicit her for the appeal. As far as she knew and was concerned, a court of law had found Adnan guilty of first-degree murder. She believed in the justice system and didn’t think such a conviction could stand without solid proof tying him to the murder. And now, all these years later, having never heard from Adnan after her letters in 1999, this murderer—or at least his lawyer—had found her home all the way across the country, where she lived with her children.

She freaked out, plain and simple, she told Sarah. And then she called the State’s Attorney’s office. How and why they connected her to Urick, a former and not current prosecutor, is unclear. Nonetheless, Urick assured her that Adnan had been convicted on irrefutable evidence and that he was now trying to game the system for a new trial.

The rub was this: Asia told Sarah that she still remembered seeing Adnan at the library after school, around 2:30 p.m., on January 13, 1999. She remembered their conversation, including his telling her that he and Hae had broken up but he still cared for her and wished her the best. She recalled her boyfriend and his friend coming to the library to pick her up, hours late to her chagrin, and her boyfriend’s irritation that she had been chatting with a good-looking guy when he arrived.

Asia remembered the storm that night that left her stranded at her boyfriend’s house, and that school was closed for the days following. She recalled the letters she wrote to Adnan after his arrest and that she’d concluded that there must be a reason he never responded.

Sarah called me, elated, but much to her surprise, news of her talk with Asia brought us little joy. My first reaction was tears. Not just tears of sorrow but of rage. Adnan knew, his family knew, I knew that Asia had never been pressured by anyone to write anything. I was glad that Sarah now knew that we didn’t make Asia say any of it, because she clearly still stood by it.

We couldn’t understand why Urick testified that Asia had told him she’d been pressured to offer her documents. Did Asia tell him that? Sarah didn’t ask Asia about it either—she didn’t want to scare her off. Sarah wanted to let her talk, give it time, and then circle back about that. She didn’t know then that she would not get to speak to Asia again for a very long time.

It didn’t really matter now. The timing of this conversation, of Asia’s affirmation to Sarah of what we knew was the truth, was the final blow, the deepest cut. If it had happened a month earlier, perhaps it could have altered the course of the appeal. But now, having lost the PCR just weeks earlier, it was too late.

* * *

Sarah continued her investigation and was now routinely speaking with Adnan a few times a week. She also met with him numerous times.

I felt a certain amount of stress over their meetings and conversations, maybe from overthinking things.

I had no idea, and no way to ask without seeming ridiculous, whether Sarah personally knew any Muslims. After what happened at the bail hearing and trial, I worried: would she be able to approach our community with total objectivity? Like any human being, she might process it all through her own biases, biases that could be primed after 9/11. And while Sarah could get to know Adnan’s family, Saad, and me on a human level because we could communicate with her freely and hang out with her in our homes, her access to Adnan would be controlled.

It would be through timed, awkward phone calls, or meetings across a table, divided by a half-pane of glass, surrounded by guards, bound to the stiff seats, psychologically restrained if not physically. She would see a large, hulking, built-out man with a long beard, skullcap, rolled-up prison-issue jeans, and DOC-printed sweatshirt; a man severely limited in his ability to show her who he fully was as a human being, looking instead like the archetypical prison Muslim.

She would not see the lanky kid who had been locked up in 1999, and her investigation would always be through this filter. Such concerns may seem overly sensitive, but having spent the last decade working on fighting negative perceptions of Muslims and the bigoted policies those perceptions end up producing, my fear was real. It is the fear any Muslim who visibly looks Muslim has—that we are immediately judged by others based on our appearance.

And then there was Adnan, who had never spoken to a journalist before. Who never had to answer questions about his innocence because those of us in touch with him never asked him. We knew he was innocent.

With a journalist, however, it needed to be said. Everything needed to be said. I wondered what it would be like for him to open up for the first time, to be challenged, to tell his story to a stranger, many parts of which he never told the rest of us. Remember that rule about looking the other way, not prying? It was simply not culturally acceptable even between us, between Adnan and his family or me, for him to share the intimate details of his relationship with Hae, his feelings about her disappearance and death, and to a certain extent even his private life as an inmate.

Every so often I’d ask Adnan how it was going with Sarah. What was their relationship like? Did she like him? Did he feel comfortable? His response would always be, “Alhamdulillah, everything is fine.”

I would try to reassure him—and myself—that she was on “our side,” that she wouldn’t put this much time and effort into this story if she didn’t think he was innocent. I wouldn’t know until later that her discussions with Adnan showed that she wasn’t ever fully convinced of his innocence.

Guilt or innocence aside, fairly early on I realized that we weren’t actually on the “same side.” I had misunderstood our relationship, and I had no one to blame but myself. Call me naïve, but one day I finally got it.

Sarah contacted me in May to tell me she’d be in the area and asked if she could swing by. With her would be one of her colleagues; they planned on doing the ride between the school and Best Buy to see if they could complete it within twenty-one minutes—the time between when school let out at 2:15 p.m. and the “come and get me call” from Adnan to Jay, according to the State.

I was excited. This exercise would debunk one of the most ridiculous aspects of the State’s narrative: that in this short span of time, while accounting for being able to get out of a school lot crowded with buses and student cars, Adnan could somehow get into Hae’s car, get her down the road to Best Buy, strangle her, move her to the trunk in the light of day in a public parking lot, then trot around the lot to make a call from a pay phone at 2:36 p.m. And I would be there when Sarah tried it and saw that it just couldn’t work.

The line got drawn right then and there, though. In the nicest way possible Sarah said she couldn’t take me along. She didn’t explicitly say why, she was kind about it, but that’s when I realized, oh wait, we aren’t actually friends. She had a job to do, and my presence could impede it.

Sarah never told me the results of her experimental drive, and I didn’t ask. I was too preoccupied because on that same day she came to show me a document she’d found in the police files. It was a document I’d never seen before, one that left my head pounding, my stomach twisted in knots.

It was a cultural research memo, and the name of the person and agency who wrote it was blacked out. I had no idea it existed, but it helped explain much of why the investigation in Hae’s murder focused on Adnan.

Adnan:

At the end of September 2013, I received a brief letter from my attorney. He informed me that he had been contacted by a journalist named Sarah Koenig. She asked him several questions about my case, and they spoke at length. He explained to me that she was interested in investigating the case, and maybe doing a story. He advised me that I could speak with her if I wanted, and he saw no harm in it. He ended his letter by stating his understanding that she would not expend the time and resources to do a story unless she felt I was innocent. I received a letter from Ms. Koenig a day or so later. I did not know at the time, but she mentioned Rabia had reached out to her, and explained everything about the case to her. I was surprised, as Rabia had never mentioned her to me. I guess she figured I would probably say no, like I always had.

Ms. Koenig’s letter was very simple and straightforward: she was considering doing an investigation into my case, and potentially doing a story. But there was no mention of her only doing a story if she thought I was innocent. So I was very confused, and really at a loss for how to proceed. I mean, her letter was very self-explanatory, but contrast it with my attorney’s. She stated she wanted to review the case, but my attorney indicated she would not do anything unless she thought I was innocent … Two entirely different things. At least to me, anyway. I had no idea what to do. On the one hand, I had always been opposed to Rabia’s suggestions of going to the media. I had been telling her no for years. And beyond making Rabia mad, I realized how hurtful it was to her. To want to help me any way she could, and I always refused. I guess she finally just went ahead and did it.

But from my attorney’s letter, I have to prove to Ms. Koenig that I am innocent. Which I cannot do. So now I am heading back to a place I never wanted to revisit. And that is to be in the untenable position of having to prove to someone that I did not do something, that I did not do, and no one proved that I did it anyway.

To be honest, I did not really expect Ms. Koenig to do much. I figured she would just read the files and do a brief story or whatever. And that would be it. I thought I might have to answer a list of questions. I had no idea what my participation would entail, and I was not really looking forward to speaking with her.

But when I spoke to Rabia about it, she explained that this was what we had been waiting for. She told me that she had been working on this for a while, and that we were at a point where we had nothing to lose. The thing I remember the most is how Rabia constantly said, “we,” as if she were in here with me. She has always said that, and it is something that has stuck with me throughout all these years. As I listened to Rabia, I realized I had no choice but to do it. Even if that meant having to go through all that stuff all over again.

Rabia mentioned that maybe this was God’s Help that I had been waiting for. And I had not really thought about it that way. I was just thinking about the negatives this experience would have in store for me. Initially, I was hoping that maybe Ms. Koenig would find something that would prove my innocence. But I had been disappointed so many times before, that I did not really have high expectations. More importantly, I did not know how to respond to her. What to say in a reply letter? Maybe she was a crime reporter who had seen it all, and believed everyone says they’re innocent. Also, I have no piece of evidence which proved my innocence. Maybe some things that make the State’s case look weak, but nothing else. So what do I do? The only thing I have ever been able to hang onto and no one can disprove is that I never had any animosity towards Hae, and that I cared about her deeply. That was all I had. So I prayed about it, and that was what I wrote to her about. And that was the point where my past emotional insecurities returned.

Was she going to think I was trying to manipulate her by lying about Hae, and how I felt about her? Maybe Ms. Koenig would believe that I selected this topic in order to tug at her heart strings. Or maybe it was because our friendship was the only thing incontrovertible at trial. The State had never been able to even offer any evidence to contradict that. I do not know, it was just that everything came back, about how nobody believed me. Maybe she would be the same, and I was not eager about opening up to someone who was going to think I was just trying to manipulate her. So now I am kind of paralyzed with uncertainty. If I do not write her, I am letting Rabia down. But if I do write her, I am risking going back to that place. I did not really know what to do. So I prayed for guidance, and the next day I just wrote the letter and put it in the mail. I did not know what Ms. Koenig’s reaction would be; but if nothing else, I have honored the obligation I had to Rabia. And if she were to think I was trying to manipulate her, well, there was nothing I could do about that.

So now it was out of my hands. I was done, and I just had to wait and see what happened. Secretly, I hoped she would not reply, and that would be the end of it. But then she wrote me back, and requested that I call her. I was fairly nervous at that point, as I really did not know what type of person she was. Maybe she would not give me a fair chance. I had no idea if she was a genuine person. More importantly, now I had to figure out how to deal with her.

See, in prison, I have learned that you cannot be yourself with everybody, because it may come back to hurt you. You cannot be generous with everyone, because some people will take advantage of you. You cannot be friendly with everybody, because it may cause you to lose respect in the sight of others. You cannot take the high road in all confrontations because some people will see it as an invitation to harm you. You have to approach every interaction with correct perspective. If you are in a cell with somebody, you may not be able to share your property with him (food, hygiene, etc.) because he may take advantage of it. If you are working with someone, you cannot joke around with him because it may cause problems when you are trying to be serious. If someone disrespects you, you cannot always walk away because it may be taken as a sign of weakness. Knowing the correct perspective has nothing to do with getting anything in return; rather, it is about protecting yourself when dealing with people who have the potential to harm you. And it is not just in prison, but in the outside world, too. And what I have learned is that whatever perspective you decide on, it is important to be consistent. To change the course once you set on it can have a bad effect.

So when I met Ms. Koenig, I had to decide what perspective was the correct one to take with her. Essentially, how to protect myself. Do I try to explain everything in my case that I think is wrong? Because that makes sense. The problem with that was it opens the door for me to be accused of manipulating or misleading her. And I do not want to experience that again. On the other hand, I could just remain quiet and simply answer her questions, and hope and pray she would come to find out those things for herself. I mean, everything is in the case; it is in the interviews and the transcripts. There’s nothing I know that is not already in there. And I have always felt confident that if someone unbiased took a look, they would find the same troubling discrepancies. But I would be taking a risk that maybe she might miss these things. So I did not know how to protect myself with her. I prayed about it, and I decided to choose the latter approach. That I would just be as honest with her as possible in answering her questions, and hope she would see the things that I felt were not right, on her own.

I also decided that I did not want to do anything that could even remotely seem like I was trying to befriend or curry favor with her. Initially, I never addressed her by her first name, even though she asked me to on several occasions. I only called her at the times she instructed me to. I only wrote her when she would send me a letter. Other than a perfunctory “How are you?” I never inquired about her personally. And whenever she asked me how I was, I would always reply with, “I’m fine, thank you.” That way I was not being personal with her. I did not want her to ever be able to accuse me of trying to ingratiate myself with her, or manipulate her. And I really tried to stick to that.

But she consistently tried to establish a rapport with me each time I called. She would always ask how I was doing, and inquire more. She would share little random things with me about her day, work, maybe what she ate for lunch. I realized that this was probably her interview style. That maybe the easiest way to get someone to open up would be to establish a familiarity. Which in turn would make a person more comfortable with opening up. She was a very kind person and seemed very compassionate. But it became very stressful, because I had every intent to be as honest with her as possible. There was no need for any strategy on her part; I just wanted to answer her questions and be done with it. And perhaps it is unfair to call it a strategy, as that may infer a negative connotation. Like I said, she is a very kind person, and I mistook her kindness to be something else. It caused me a great deal of anxiety, as I felt that I was not being true to my principles regarding how I treat people.

I had spent all these years trying to be personable towards others. But to be in a position where I am constantly speaking with someone who is kind enough to share all these things with me, and I cannot reciprocate that kindness? Because I am afraid of being accused of trying to manipulate her; I cannot ask how she is doing, or about her day. And it really hit me hard one day when she asked me why I would always reply, “I’m fine, thank you” whenever she inquired about my well-being. I felt I was being terribly rude to her, and ungrateful. It seemed as if it did not matter to me that she cared enough to ask how I was. One time, she shared with me that she had recently experienced the loss of a family member. It was heartbreaking to hear the grief in her voice, but I was afraid to express my sympathies to her because I did not want to appear as if I had an ulterior motive. I could not change my approach; my life in prison had taught me to be consistent. I mean, it was a horrible feeling. Can you imagine what it is like to be afraid to show compassion to someone out of fear that you would not be believed? Especially when that someone has been nothing but compassionate with you? She had exhibited a great deal of kindness to me, and I was afraid to treat her the same. I was so ashamed of myself at that time.

I just tried to be as honest with her as possible and I prayed that she would come to learn those things about my case. And she did. She even learned some things that I did not know. There was nothing huge, no smoking-gun. But they are things that I believe strengthen my claims of innocence. Facts and evidence that should exist if I had truly committed this crime; they were not there. And there were facts and evidence that further discredited the State’s case and theory. And I was grateful for that. Because it was all in the transcripts, interviews & tapes. I did not need to point her towards anything. Like I said, I have always believed that a person could find these things out for themselves. She arrived at all her conclusions on her own. It had nothing to do with me. And no one could ever accuse me of manipulating her into any of that.

At least, I thought so up until the day when I asked her about what made her decide to do the story. She had been pretty clear with me that she could not say I was innocent. To the contrary, the tone and content of most of her questions led me to believe she felt that I was lying about many things. But the words from my attorney’s letter always stayed in my mind; that she would not do the story unless she thought I was innocent. So I figured she decided to do the story because of Hae, or because the case appeared to be very wrong. But she responded that it was because of me, and that it seemed like I was a good person. And that it was difficult to reconcile the person she had spent so many hours interviewing with the person who committed this heinous crime.

To hear this was very frustrating, because it took me right back to square one. Instead of me being accused of manipulating her through the case, now I am going to be accused of being manipulative in my personal interactions with her. Which I tried to limit anyway, and I never intended to have and specifically sat out trying to avoid. And I got pretty upset when she said that. And I realize this all may sound incredibly ridiculous. Or even make me sound crazy. And maybe I am crazy. But it was so frustrating, because no matter what I do, or how many safeguards I install, I can never protect myself from being accused of manipulating someone. No matter how hard I try, or how careful I am. Also, because I’m just tired of hearing people say similar things to me. That they do not know why I am in prison, because I am such a nice guy. Guards say it, other prisoners say it. Granted, they do not know the details of my case, but still. I just wish someone would say its because of the faulty evidence, and not because of me. And I realize it makes me sound like an idiot to say that, because I should be grateful for anyone to feel that they do not believe I could commit such a heinous crime.

So now I am stressed out and just waiting for this whole interview process to be over. The very thing I have worked on all these years (just trying to be a good person) and the very thing I’ve always tried to avoid (being accused of manipulative behavior) have now had a cosmic collision. I am now going to be accused of demonstrating good behavior to manipulate Ms. Koenig. No matter what I do, it is as if I can never escape this. By then, I am just waiting for her to tell me we are done, and I can finally tell you I did my best. And at that point, it didn’t matter to me how her story portrayed me. Guilty or innocent; I would just be glad to be done with the whole thing.

Can you imagine what it’s like to never be able to be intuitive about the most important thing in your life? I could never just talk about my case with Ms. Koenig. I had to always analyze and evaluate every response I gave her, because I felt she had a general disposition to believe I was never telling the truth. It took me a long time to rid that of myself in my personal life. Prison really helped that. But I can never get rid of it when it comes to talking about my case. I am always overthinking, analyzing what I say and how it sounds. And all this thinking is not for personal gain. It is to protect myself from being hurt. Not from being accused of Hae’s murder, but from being accused of being manipulative. And I know it seems crazy, but I cannot control how I feel. And it is so frustrating to know that what you’re feeling is crazy but there is nothing you can do about it.

Ms. Koenig had no way of knowing, but she set the tone for me to experience this with one of the first questions she ever asked me. She stated that she had watched the video of my first trial, and she saw me sitting at the defense table during a break in proceedings. I was reading a small book, and she asked me what it was. I told her it was a Quran my dad had sent me. She next asked if I was reading it to make the Judge think I was religious? That triggered something in me, a hopeless feeling that I would never be able to convince her I was innocent.

I will always be grateful for the compassionate manner she demonstrated towards me. As I mentioned before, she never articulated to me her belief that I was innocent. To the contrary, I always felt she believed I had some involvement in Hae’s murder. But she was always very kind to me, and I guess that caused me to respect and appreciate her even more, as a person …

It is not that I do not care if people believe I am innocent or not. It is just that I cannot let it affect me. When I was younger, it caused me a great deal of emotional distress to feel that everyone believed I committed this crime. Eventually, I realized I could not continue to be miserable anymore, as it was beginning to crush my spirit. I had to learn that it was destructive to allow other people’s opinions to have an influence over me. It took a long while, but I was finally able to reach a point where I was not concerned with people’s opinions of my innocence or guilt. I realized the emphasis must be placed on fighting my case in the proper arena. And I am grateful that God allowed me to develop that insight, because it has helped sustain me till today.