FINALLY, AFTER TWO YEARS OF HAGGLING AT Panmunjom and tens of thousands of American lives expended along the front, a cease-fire agreement was signed. The designated time for the cease-fire was July 27, 1953 at 10:00 P.M. This was the time for all hostilities to cease.

We watched the clock intently. Would they actually stop fighting? Would the long bloody war finally end? Would we go home at last? We had our doubts, and for good reason because of the number of times that some last minute disagreement caused a walkout from the negotiations.

The companies on the front were ordered to send out listening posts and to run reconnaissance patrols into the valley as usual. However, we were ordered not to carry “live” ammunition. At our company level, however, we modified the instructions slightly and directed the troops to carry a magazine in their weapon but not to carry a round in the chamber. We did not trust the situation enough to send an unarmed patrol into the valley. We were instructed that we could fire only if the enemy directly fired us upon. There was to be no firing of weapons after 10:00 P.M., accidental or otherwise.

Early in the evening, a few guys in advanced positions down the finger of the hill fired off a few rounds. I went down the trench to see if there was anything happening. They were just “letting off steam” and loudly expressing their opinions about the war. The Chinese also expressed their view of us and the war by throwing a few token 76 mm rounds from the closest hill. As the clock ticked off the remaining minutes of the war, another sergeant and I climbed on the ridge line and watched the valley floor for activity. We drew our pistols and fired a ceremonial round at the dark, ominous Chinese hill to finish off the war.

The ceasefire began at 10:00 P.M. as planned. There was no more firing from either side. I believe that we, Americans and Chinese alike, all finally had our fill of war. All along the line that night there was total silence. The night sky was semi-darkened—bathed in natural summer moonlight and an unnatural low light glow projected out from the search light unit about a half-mile down the line near our positions. This was the most incredible silence I’d heard in my life. Not a tracer was seen dotting the sky, not an exploding round was heard. We marveled as we walked around our positions, unconcerned as to whether Ole Joe was going to test our resolve in some way during the night. We were ordered to pull our half-on, half-off watch as always, but seemingly no one minded being awake that night. No one felt much like sleeping; the excitement was too much. The evening passed without incident, the war was really over.

A poem by Oscar Williams (1945) entitled One Morning the World Woke Up, written for an earlier war, expressed the situation well:

No trucks climbed into the grooves of an endless road,

No tanks were swaying drunken with death at the hilltop,

No bombs were planting the bushes of blood and mud,

And the aimless tides of unfortunates no longer flowed:

a break in the action at last...

All had come to a stop.

****

Our orders for the pullback the next day were to saddle up and take all weapons, supplies, or anything of military worth. Nothing of value was to be left. The plan for the evacuation involved withdrawal back to a line two kilometers to our rear where we would set up positions and hold them. This imaginary line would be established as a demilitarized zone that extended the length of the peninsula with no troops stationed or moving between the troop-free zone. All of the precious real estate that we had spent so long wrestling away from the Chinese and North Korean enemies, all of the concertina wire, all of the miles of our trench line and the network of mysterious Chinese caves would now become a part of the four kilometer demilitarized zone—the DMZ.

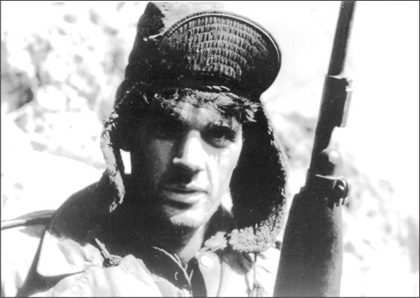

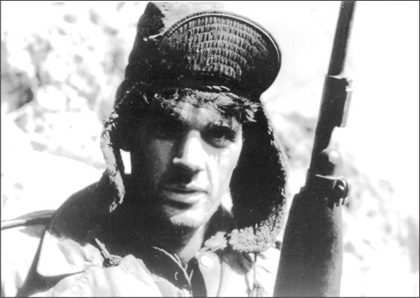

The author, SFC Jim Butcher, age 19. March 1953.

Dawn broke on the morning of July 28, 1953 much like it had the many mornings I spent in Korea. I awakened from a short, light nap and felt stiff and numb from sleeping on the hard commo wire bunk. As I looked around at the grimy faces of the others in the trench we were stunned by the silence of the morning. This day was indeed different—there were no shells, no machine gun fire, and no yells for “medic.” There was nothing but the stone silence—much like the sounds of a cemetery. All movement seemed to be in suspended animation as we walked around in disbelief.

Upon leaving the bunker, the first thing that I did was climb up on the ridge line, outside the trench, and scan the Chinese hill in the distance with my binoculars. I was expecting to see the usual barren hills devoid of vegetation and human life. I was astounded by the sight of movement across the valley. Instead of the bleak, naked hills that we had grown so accustomed to observing for so many months, we witnessed an incredible sight across no-mans-land toward the Chinese lines. There, as far as the human eye could see, were long lines of Chinese soldiers stretching from their forward caves and trenches all the way back to their rear echelon areas in the distance.

Thousands upon thousands of Chinese soldiers formed this anthill of activity, standing a few feet apart, passing supplies and equipment backward in an endless assembly line, looking like robots. We watched this mechanical procession for a long time, marveling at the immense number of enemy soldiers that were visible. Had we known the extent of their forces a few days before, had we known the locations from which these men moved out large guns and small, we would have not been so complacent and comfortable of our own strengths and capabilities. It appeared to us that everyone in China was here moving equipment back away from the now demilitarized zone.

Our own movements toward the rear were less spectacular. We half carried, half tumbled our way off the hill, moving what weapons, ammunition, and personal items we had with us. At the bottom were waiting trucks, moved up as close to the MLR as topography would allow.

We left a lot of things on the hill. All of the refuse that had accumulated, all of the spent cartridges that we had not policed up, all of the discarded, worn-out clothing. An extra steel helmet, the old blankets with holes in them, empty ammunition tins, a leaky water can, the miles of communication wire, the commo wire bunks, and a calendar circled with the date July 28, 1953—all were left behind. Along with the intentionally discarded items of war that we no longer needed were also some things left by accident, such as one corporal’s harmonica, another’s picture of his girl friend. Everything that was not taken was doomed to remain as it was, left for decades. The trenches and all that remained were turned over to the rats—the new owners of those digs.

Some guys wrote notes that they left tied to bunker posts for posterity to find. Some of the notes were simple statements, such as “Johnny slept here!” Others were more blunt and aggressive in explaining what the sender thought about the enemy with such statements as “Chinks stink!” Others, trying to be more philosophical, wrote what they thought about the war or the Chinese, but almost always these homilies were punctuated with clear, Army-styled four letter words.

****

The new DMZ, the buffer zone between North Korea and South Korea, was a strip of earth 249 miles long and four kilometers wide. It has been officially off limits to forces from either side except a few on some official duties, usually in the corridor between Panmunjom and Seoul. Some intruders have made their way into the DMZ from time to time; otherwise, things are pretty much as we left them except what time and the ever-present rodents have done to them. The North Korean military maintains a strong military presence, over a million men, around the Panmunjom area and periodically engages in violations of the DMZ by sending troops into the buffer area. In 1996, for example, the North Korean Army sent more than 300 soldiers in groups of ten to twenty into the DMZ to conduct maneuvers. The United States and South Korean forces have also had infractions of the buffer zone with people “wandering” into the DMZ on occasion. In 1977 an American helicopter was shot down, killing three people. In 1995 an American aircraft was shot down in North Korean territory, killing one of the airmen on board.

Tensions have erupted along the buffer zone on numerous occasions. For example, North Korean solders killed two American officers with axes when they were trimming trees near Panmunjom.

The South Koreans, for protection, have built a two-and-a-half story concrete wall running nearly the entire width of the peninsula (except the DMZ at Panmunjom). The North Korean Army has dug large tunnels under the DMZ; tunnels that could be used to infiltrate or attack the South if they were so disposed. Four extremely large tunnels have been discovered thus far under the DMZ and it has been estimated that there are around twenty total.

In all likelihood, in the decades that have passed, the trench works have rotted away and collapsed. The hills that were once bald have likely been restored by nature as best as it can, with free ranging vegetation now covering the discarded shell fragments and bones that still lay littered about. Old Baldy probably even has a growth of brush covering the once barren slopes. The wounds to the hills have, in all likelihood, healed their scars of war far more efficiently than the people who fought on them. These scars still protrude from our consciousness—covered only by a superficial layer of civilization and more positive events that have come since the war.

About a week after the armistice agreement ended the fighting, our company was ordered to move farther back to an area a few miles north of Seoul, to Camp Casey, and the entire company except a guard detachment was moved out on trucks. I was left with three other men in charge of a “baggage detail” to guard the company supply and baggage until transportation could be sent back to pick us up in a couple of days. We were left with enough C-rations for the two-day period. Unfortunately, three days later, we were still waiting; with our food and water gone, no communications with the company, and no transportation. We had been deserted. We considered the various options and didn’t find many available. We had plenty of weapons and ammunition so we decided, like our forefathers of old, to hunt ourselves some dinner.

Unfortunately, the Korean War, with all of its noise and destructiveness, had long since scared away most of the game from these hills. The only prospects for our hunt we saw were a few very high flying birds. So we tested our marksmanship, initially with M-1 rifles. After a few shots, we recognized that this would not accomplish much so we brought out one of the BARs and tried automatic weapons fire. Success! We hit one and it fell to the earth. It was a bit mangled and not worth making into a meal. More time passed and still no trucks. We opened a few of the duffle bags to look for food and found only a couple of candy bars. Finally, one afternoon a ragged truck came by with two Korean Service Corps civilians who were out scrounging around the countryside for what ever they could find. They were very surprised to find us there and came over to inquire about us. We told them the situation and they agreed (for a price) to sell us some food and water and help us locate our unit. They returned a few hours later with cooked rice, kimchi, and some other unrecognizable items for our empty mess kits. We ate whatever they provided. They also brought some whiskey that they were happy, by then, to sell for some of the company blankets and equipment (shovels) that we were happy to barter. We rationalized purchasing the whiskey as having a need for further sustenance.

The remainder of our wait for the company to retrieve us was more pleasant and our hunt for animals became a bit more aggressive as we staggered around firing uselessly at anything we thought might be edible. Some might have thought that we had restarted the war had they been close enough to hear the sounds of our hunt. After five days our company retrieved us, with an appropriate apology. Before I had time to register a complaint to the CO (my rotation date was long overdue now) he cheerily told me that I was leaving the next day for Inchon then home. I could hardly believe those words. Going home, at last.

My return to the United States, originally scheduled by air transport, was changed because of congestion in the military transportation pipeline of rotation. I drew the short straw and was assigned to a troop ship that made me wait a few days for its arrival. When I finally boarded another Kaiser ship for the three-week return journey it seemed like a much longer voyage on the return because of the anticipation we were all experiencing.

In addition to the several hundred GIs in the rotation draft, our ship contained a contingent of about 200 released POWs who were kept completely segregated from the rest of the returning veterans. We were told that we were not to talk to them or to try to exchange any items with them. I was curious to learn about the treatment they had experienced at the hands of the North Koreans but had no opportunity to do so. There was some talk during the voyage about the POWs having thrown one of their group overboard because he had collaborated with the enemy but this could have been a rumor. There was always an abundance of rumors floating around the ship with so many idle soldiers sitting about.

As with the trip over on the troop ship, to pass away the time, I spent some profitable hours at playing poker, but much of my time on deck was spent just in reverie and anticipation of what the future might hold. This was not an unpleasant occupation and served to pass the time away. I wondered about what life would be like without having to face the ever-present danger of sudden death?

Finally, the troop ship passed beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, providing everyone with the most spectacular and memorable entry into the United States. The tug maneuvered our ship into the long concrete berth at Ft. Mason. Once the ship was secured and the customary wait time had dissipated, the long line of khaki figures, each with a similar, brown duffle bag, began its snail like pace in disembarkation. The facelessness of military transfer continued as we made our way onto the concrete pier. A five-piece military band struck up a military welcome; several civilians lined the wharf watching the column of troops in hopes of recognizing one of the uniformed figures proceeding down the gangway.

On the pier, at the bottom of the ship’s gangway, stood a crew of Red Cross volunteers handing out coffee and a donut to anyone who stretched out his hand as we formed into a somewhat ragtag formation. Soon, we were herded into a large hall and informed of the processing procedures and plans for moving us out, hopefully to our homes, in short order. We were provided a very welcome diversion from the troop ship food with a steak dinner and a bunk for the first night on friendly shores. The next day, and without fanfare or celebration, we were cast into the four winds—to our respective corners of America. There were no parades, no grand speeches about a job well done, no waving ladies dressed in attractive clothing. There was only the grateful understanding existing among ourselves that we had been the lucky ones. We were home again.

After my post-Korea leave I was reassigned back in the 82nd Airborne Division, this time to the 505th Airborne Infantry Regiment. My status was different, with my rank of sergeant first class I was given a job as a platoon sergeant in an airborne infantry company. I was not just a paratrooper who had to knuckle under to the spit and polish of garrison duty, but now I was someone who had to inflict it upon others.

Having obtained all my rank under combat conditions, I was not fully up to speed on what was required of non-coms in garrison duty, so I was a bit awkward as to procedures. Moreover, I was young to be a platoon sergeant in the 82nd, only twenty years old, while most of the other non-commissioned officers were old timers who had been well schooled in the ins-and-outs of dress parades and general inspections. I was helped along a bit by a couple of squad leaders who had been in combat units and seemed to recognize and sympathize with my lack of facility with barracks routine. Needless to say, I felt somewhat of a misfit with the day-to-day routines of barracks life. I only felt at home during the occasional times when the unit went into the field, especially when it came to actually running simulated combat field problems.

When I first showed up at my new company, the first sergeant assumed that I would return to jump status now that I was back in the 82nd Airborne. I had not made that assumption at first but with nine months left on my enlistment, and considerable official harassment, I agreed to jump again (after he implied that not to do so would indicate that I was chicken). Sergeants have only a few limited ways to motivate their troops and some form of intimidation was usually successful!

So, it was once again jump time—but this time I did not have the opportunity for any training or even a brief refresher course. I was pretty rusty not having jumped in over a year and a half. Moreover, there was new equipment to get used to—a different plane (C-119) and a new type of chute (T-10).

The top sergeant, a very experienced jumper, appeared to want to “test out” my mettle so he decided that he would jump with me that day. All went as expected except that the sergeant (to see if I had the guts to follow) did not wait for the green light (the usual signal that the aircraft was over the drop zone). Instead, he jumped on the red light trying to jibe me into doing the same.

Not to be outdone by the top sergeant, I did likewise, all the while thinking that I was nuts leaping into the air over I knew not where. When our chutes opened, we found ourselves drifting down over the forest—tall North Carolina pine trees staring up at us some distance away from the drop zone. The sergeant, grinning widely as he descended, knew what he was doing and was steering his chute adeptly toward the sandy drop zone—he made the strip of soft sand handily. I, not so adept, landed in a tall tree. I was now back in the challenge of the airborne infantry!

As I settled into the routine, I came once again to enjoy some parts of the military duty. The Company Commander thought it would be desirable for me to increase my usefulness to the company and sent me off for a week-long training course called Heavy Drop School. This course taught NCOs how to rig heavy equipment such as jeeps, three-quarter-ton trucks, artillery pieces, and so forth for dropping from planes. This was an interesting experience and when the course was finished we had to make a practice jump along with some of the equipment that we rigged. I was on a team that rigged a three-quarter-ton truck for dropping. Fortunately, the rigging worked and did not crash to the earth embarrassing the riggers.

****

Toward the middle of 1954, my initial enlistment in the Army began to draw to a close and I was at a major crossroads in my life. As long as I could remember, I had wanted to be a career soldier. Now, I was in a position that these goals were being realized but I needed to decide what to do next. I considered several options.

For a time, I was tempted to re-enlist into a new unit that was just being formed called the Green Berets, an elite group that was being built around a corps of airborne troops, but I thought that this organization was going to be heavy into the training and dress rehearsal aspects of life, and might simply be more of the same only worse in terms of garrison duty.

For a while I also considered joining another Army (France)—one that was enmeshed in another Asian war—Vietnam. The French were about to be kicked out of their colony in Indochina and were holed up at a place called Dien Bien Phu. Another Korean vet and I discussed the possibility of joining them, and learned that the Foreign Legion was seeking enlistments to fight in South East Asia. My friend and I spent a lot of time at the NCO club at Ft. Bragg during my final months, planning a new adventure. We looked into the possibility of going to France and joining in their fight. We even went so far as contacting the French embassy for information. The French were interested in the possibility of having some combat-tested recruits. However, they could not assure that we would get any rank based on our prior service. Not wishing to start another military career in a strange Army as lowly privates, we scrapped the idea.

Another possibility that I considered was to re-enlist in the American Army with the goal of going into training to fly helicopters. The Army was beginning to expand in the area of air cavalry, and this duty had an inherent appeal to me given the interest in aviation that I had since I was young. But there was no assurance that I would get such an assignment if I did re-enlist for six years. When I talked with the recruiter on base about the likelihood of getting assigned to helicopter school, he indicated that there was about a 50/50 chance. Then I inquired as to where I might be assigned if helicopter training was not available to me. The recruiter said in a very serious and quite enthusiastic voice, “You could always come back and be a platoon sergeant in the 82nd Airborne!” But in the end, I recognized that the fire in my belly for things military had diminished somewhat, and I decided to accept my discharge when my enlistment expired in May 1954.

So, at the age twenty, for better or worse, I left the home that I had found in the Army for an uncertain future as a civilian.