Main Points:

For thousands of years, many parents have had a “gut feeling” that their infants were crying from bad stomach pain. The three tummy-twisting problems that became the prime suspects of causing colic were intestinal “gas”; pooping problems; and “overactive” intestines.

Babies often gulp down air during their feedings. Here are tips to help your baby swallow less air and to burp up what does get in:

1. Don’t lay your baby flat during a feeding. (Imagine how hard it would be for you to drink lying down, without swallowing a lot of air.)

2. If your baby is a noisy eater, stop and burp him frequently during the meal.

3. Before burping your baby, sit him in your right hand, with your left hand cupped under his chin. Then bounce him up and down a few times. This gets the bubbles to float to the top of the stomach for easy burping. (Don’t worry, it won’t make him spit up.)

4. The best burping position: Sit down with your baby on your lap, with his chin resting comfortably in your cupped hand. (I never burp babies over my shoulder, because their spit-up goes right down my back.) Next, lean him forward so he’s doubled over a little. Give his back ten to twenty firm thumps. Babies’ stomachs are like glasses of soda, with little “bubblettes” stuck to the sides. So thump your baby like a drum to jiggle these free.

Let’s examine each individually and then I will explain why none of these nuisances is the real cause of colic.

Most infants have gas—often. I’m sure you’ve witnessed virtuoso performances of burping, tooting, and grunting several times a day. Many parents are convinced this intestinal grumbling causes their baby’s cries.

Parents who think colic is a gas problem have two powerful allies: grandmas and doctors. For generations, grandmothers have advised new moms to treat their baby’s colic by avoiding gassy foods, burping them well, and feeding them sips of tummy-soothing teas. For decades, doctors have suggested that mothers alter their diet or their child’s formula, or give burping drops (simethicone) to reduce a baby’s intestinal gas.

However, with all due respect to grandmothers and doctors, fussy newborns have no more gas in their intestines than calm babies. In 1954, Dr. Ronald Illingworth, England’s preeminent pediatrician, compared the stomach X rays of normal babies with colicky babies and found no difference in the amount of gas the calm and cranky babies had at their peaks of crying. In addition, repeated scientific experiments have shown that simethicone burping drops (Mylicon and Phazyme) are no more helpful for crying babies than plain water. It turns out that the gas in your baby’s intestine comes mostly from digested food, not from swallowed air.

Some parents worry that constipation is causing their baby’s colic. Babies struggling to poop can look like they’re in a wrestling match. However, constipation really means hard poop, and only a few, fussy, formula-fed babies suffer from that. Most infants who groan and twist usually pass soft or even runny stools.

If grunting babies aren’t constipated, why are they straining so hard?

1. To poop, an infant has to simultaneously tighten his stomach and relax his anus. This can be hard for a young baby to do. Many accidentally clench both at the same time and try to force their poop through a closed anus.

2. They’re lying flat on their backs. Just think of the trouble you’d have trying to poop in that position!

Black Tar to Scrambled Eggs: What Are Normal Baby Poops Like?

Few new parents are prepared for how weird baby poops are. For starters, there’s the almost extraterrestrial first poop—meconium. (Robin Williams described its tarry consistency as a cross between Velcro and toxic waste!) Within days, meconium’s green-black color changes to light green and then to bright, mustard yellow with a seedy texture. (The seeds are miniature milk curds.)

In breast-fed babies, poops then turn into runny scrambled eggs that squirt out four to twelve times a day. Over the next month or two, the poop gradually becomes thicker, like oatmeal, and may only come out once a day or less. (The longest period I’ve ever seen a healthy, breast-fed baby go without a stool has been twenty-one days. However, if your baby is skipping more than three days without a stool, call your pediatrician to make sure he’s okay.)

For bottle-fed babies, poop may be loose, claylike, or hard in the first weeks. The particular formula a baby drinks can affect this consistency. Some infants get constipated from cow’s milk formula, while others get stopped up by soy. A few are even sensitive to whether the formula is made from powder or concentrate.

Babies grunt and frown when they poop because they’re working so hard to overcome these two challenges, not because they’re in pain! (For more on infant constipation, see Chapter 14.)

“Overactive” Intestines—Crying, Cramps, and the Gastro-colic Reflex

Does your baby cry and double up shortly after you start a feeding? This twisting and grunting may look like indigestion, but it’s usually just an overreaction to a normal intestinal reflex called the “gastro-colic reflex” (literally, the stomach-colon reflex).

This valuable reflex is the stomach’s way of telling the colon: “Time to get rid of the poop and make room for the new food that was just eaten!” If you’ve noticed that your baby poops during or after eating, this is why.

A baby’s digestive system is like a long conveyor belt. At one end, milk is loaded into the mouth five to eight times a day. It is quickly delivered to the stomach, and then is slowly carried through the intestines, where it is digested and absorbed. Whatever milk isn’t absorbed gets turned into poop and is temporarily stored in the colon.

When the next meal begins, the stomach telegraphs a message to the lower intestines, commanding them to squeeze. The squeezing pushes the poop out, making room for the next load of food. This message from the stomach to the colon is called the gastro-colic reflex.

Most infants are unaware when this reflex is happening. Others feel a mild spasm after a big feeding or if they’re frazzled at day’s end. But for a few babies, this squeezing of the intestine feels like a punch in the belly! These infants writhe as if in terrible pain.

As you might imagine, the gastro-colic reflex can be even more uncomfortable if your baby is constipated and his colon must strain to push out firm poop. However, most babies who cry from this reflex have soft, pasty poops. They cry because they are overly sensitive to this weird sensation.

It’s not what we don’t know that gets us into the most trouble, it’s what we know … that just ain’t so!

Josh Billings, Everybody’s Friend, 1874

Despite the fact that many people think gas causes colic, it and the other Tiny Tummy Troubles (TTT’s) don’t explain this terrible crying because:

Anti-Spasm Medicines: Soothing Crying Babies into a Stupor

From the 1950s to the 1980s, doctors armed parents with millions of prescriptions of anti-cramp medicine. Some doctors used Donnatal (a mix of anti-cramp medicine plus phenobarbitol) while others preferred Levisin (hyocyamine). Both are cramp-relieving and sedating, and both are still occasionally prescribed by doctors today.

However, of all the anti-spasm drugs recommended for colic, Bentyl was by far and away the most popular. In 1984, 74 million doses of it were sold in Britain alone. But Bentyl turned out to be the most dangerous of all the tummy drugs. In 1985, doctors were horrified to discover that a number of colicky babies being treated with it suffered convulsions, coma—even death.

In retrospect, it’s likely that anti-cramp medicines work not because of any tummy effect, but because they induce sedation as an incidental side effect.

The TTT’s also fail to explain five of the ten universal characteristics of colic and colicky babies:

Over the past thirty years, scientists have discovered several new problems that cause stomach pain in adults. I call these conditions “Big Tummy Troubles” because they are actual medical illnesses, not merely burps and hiccups.

As each new illness was reported, pediatricians carefully considered if it might occur in infants and explain the inconsolable crying that plagues so many of our babies. Two of these Big Tummy Troubles have been scrutinized as possible keys to the mystery of colic: food sensitivities and stomach acid reflux.

If you are breast-feeding, you may have been counseled to avoid foods that are too hot, too cold, too strong, too weak, as well as to steer clear of spices, dairy products, acidic fruit and “gassy” vegetables.

Likewise, mothers of colicky, bottle-fed babies are often advised to switch their child’s formula to remove an ingredient that may cause fussiness.

Over the years, experts have considered three ways a baby’s diet might trigger uncontrollable crying: indigestion, allergies, and caffeine-type stimulation.

Passing up garlic, onions, and beans seems reasonable to most people. These foods can make us gassy. But if gassy foods are hard on a baby’s tummy, why can breast-feeding moms in Mexico eat frijoles (beans) and those in Korea munch kim chee (garlic-pickled cabbage) without their babies ever letting out a peep?

Nevertheless, I do think it’s reasonable for the mother of an irritable baby to avoid “problem” foods (citrus, strawberries, tomatoes, beans, cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, peppers, onion, garlic) for a few days to see if her baby cries less. However, in my experience, only a handful of infants improve when these foods are eliminated. Studies even show that babies love tasting a smorgasbord of flavors. So don’t be surprised if your little one sucks on your breast more heartily after you’ve had a plate of lasagna loaded with garlic!

Allergies are part of our immune system, protecting us from unfamiliar proteins (like inhaled pollen or cat dander) that try to enter our bodies.

As a rule, if you have an allergic reaction you’ll sneeze, because the fight between your body and the allergens typically takes place in your nose. With infants, however, the battleground between their bodies’ immune system and the foreign protein is usually in the intestines. Your baby’s intestine is not yet fully developed. Her immature intestinal lining allows large, allergy-triggering molecules to enter her bloodstream like flies zooming through a torn screen door. Over the first year of life, your baby’s intestinal lining gradually becomes a much better barrier to these protein intruders.

For many years, doctors believed babies could be allergic to their own mother’s milk. In 1983, Swedish scientists proved this impossible. They demonstrated that babies whose colic improved when they were taken off their mother’s milk were sensitive not to their mom’s milk itself but to traces of cow’s milk that had floated across the lining of the mother’s intestines and snuck into her milk.

Please don’t be overly concerned about your diet troubling your child. As a rule, babies rarely develop allergies to the foods their moms eat. The two biggest exceptions to that rule, however, are cow’s milk, the proverbial eight-hundred-pound gorilla of baby allergies, and soy, coming in a not-too-distant second place (about ten percent of babies who are milk allergic are soy allergic as well).

I tell my patients it should come as no surprise that some babies develop an allergic reaction to cow’s milk. After all, this food is lovingly made by cows for their own babies, and it was never intended to feed our hungry tots.

Cow’s milk protein starts passing into your breast milk within minutes of drinking a glass. It reaches its peak level about eight to twelve hours later and it’s out of your milk in twenty-four to thirty-six hours. Fortunately, most babies have no problem tolerating this tiny bit of milk protein. However, sensitive babies begin reacting to it within two to thirty-six hours of consuming it.

Milk-allergic babies may suffer from a number of bothersome symptoms besides severe crying. I have cared for infants whose milk allergy gave them skin rashes, nose congestion, wheezing, vomiting, and watery stools. The intestines of some of my patients have gotten so irritated by allergies that they produced strings of bloody mucous that could be seen mixed in with their stools. Although blood in your baby’s diaper will raise your heart rate, it is usually no more ominous than finding blood in your mucous when you blow your nose. Be sure to contact your baby’s doctor, however, to discuss the problem.

Some babies are supersensitive. They jump when the phone rings and cry when they smell strong perfume. It should come as no surprise that some babies also get hyper from caffeine (coffee, tea, cola, or chocolate) or from stimulant medicines (diet pills, decongestants, and certain Chinese herbs) in their mom’s milk.

While many babies are unfazed when their mothers drink one or two cups of coffee, even that small amount of caffeine can rev a sensitive baby up into the “red zone.” The caffeine collects in a woman’s breast milk over four to six hours and can make a baby irritable within an hour of being eaten.

Pediatricians have also examined stomach acid reflux (also known as Gastro-Esophageal Reflux, or GER) as a possible colic cause. This condition—where acidic stomach juice squirts up toward the mouth, irritating everything it touches—is a proven cause of heartburn in adults.

Now, for most babies, a little reflux is nothing new. We just call it by a different name: “spit-up.” Since the muscle that keeps the stomach contents from moving “upstream” is weak in most babies, a bit of your baby’s last meal can easily sneak back out when she burps or grunts, especially if she was overfed or swallowed air.

Most newborns don’t spit up much, but some babies “urp” up prodigious amounts of their milk. Fortunately, most of these babies don’t suffer any ill effects from all this regurgitation. The greatest problem caused by their vomiting is often milk stains on your sofa and clothes.

On the other hand, infants with severe GER are plagued with copious amounts of vomiting, poor weight gain, and occasional burning pain. (In some babies, stomach acid travels just partially up the esophagus, causing heartburn without vomiting.)

When should you suspect reflux as the cause of your baby’s unhappiness? Look for these telltale signs:

Big Tummy Troubles Strike Out as the Major Cause of Colic

Food sensitivity and acid reflux can make some babies scream, but do the Big Tummy Troubles (BTT’s) explain most cases of colic or just a small number of ultrafussy babies?

In my experience, five to ten percent of very fussy infants cry due to food sensitivity from cow’s milk or soy, and one to three percent of them cry from the pain of acid reflux. That notwithstanding, Big Tummy Troubles (BTT’s) are not the cause of colic for the majority of fussy infants:

The BTT’s also fail to explain five of the ten universal characteristics of colic and colicky babies:

Any mother who has felt fear and anxiety surrounding the birth of her new baby might wonder if these disquieting feelings could affect her newborn. This was Trina’s concern.…

With her ruby lips and lush, black hair, Tatiana was exquisite. But her delicacy in form was balanced by a strong and feisty temperament. She reflected her parents’ passionate personalities, and Trina and Mirko could not have been more thrilled. However, as the weeks went by, they became more and more frustrated as Tatiana’s feistiness turned into prolonged periods of screaming.

Trina called one afternoon after her four-week-old daughter had been particularly cranky. She confided, “I’m a very sensitive and intuitive person. Is it possible that Tatiana is too? Is it possible she’s upset because of all the stress I’m under?”

It seems that the joy Trina and Mirko had felt after Tatiana’s birth was tempered by Trina’s painful recovery from a cesarean section and then the destruction of their possessions from a flood in the apartment above theirs, days after they brought Tatiana home.

“The nest we created for our baby collapsed like a house of cards and we had to move into our friend’s living room. When Tatiana developed colic at three weeks of age, I couldn’t help but think her screams stemmed from all the anxiety she felt from me during this terribly upsetting time.”

The birth of an infant brings with it such a wonderful but weighty responsibility that it’s a rare parent who doesn’t feel some anxiety and self-doubt. Many new mothers confide in me that they feel overwhelmed because:

Aye, aye, aaaaaye! Am I really ready for this?

Mothering a baby is a magnificent experience, but it’s neither automatic nor instinctive. Unless you’ve spent lots of time baby-sitting or helping with younger siblings, don’t be surprised if your new baby makes you feel you need six arms—like a Hindu deity. For most women, mothering their newborn is the toughest job they’ve ever had!

After talking to thousands of new mothers, I’ve made an “Aye, Aye, Aye” list of the top ten stresses that can undermine a new mom’s self-confidence—and make even a goddess start to crumble:

1. Intense fatigue

2. Inexperience

3. Isolation from loving family and friends

4. Insufficient isolation from intrusive family and friends

5. Inconsolable crying (the baby’s, that is)

6. Irritating arguments with your spouse

7. Instant loss of job income and gratification

8. Insecurity about your body

9. Instability of your hormones

10. Indelible barf stains on every piece of clothing you own

Of course, these problems pale when compared to the vivid joy and feeling of purpose your baby brings into your life. However, new mothers enter a vulnerable psychological space after giving birth, and fatigue and fear can even further distort your perceptions. You’re in the midst of one of life’s most intense experiences and, particularly if you have a colicky baby, waves of anxiety and depression may repeatedly wash over you during these initial months. (For more on postpartum depression, see Appendix B.)

Fortunately, the pressures you feel today will soon melt into a warm love that will probably be more powerful and profound than any other you have ever felt. In the meantime, please be tolerant of yourself, your husband, and, especially, your baby.

Colicky infants are born, not made.

Dr. Martin Stein, Encounters with Children

It’s common for mothers of irritable babies to feel jealous and self-critical when they see other moms with easy-to-calm infants. Those feelings can cast a shadow over a woman’s confidence and make her wonder if her anxiety causes her baby’s crying.

Fortunately, during the first few months of life babies aren’t able to tell when their mothers are distressed and worried. Remember, babies are just babies! They are not born with the ability to read their mother’s feelings as if they were messages written on her forehead in lipstick. These little prehistoric creatures even have trouble … burping. So don’t worry about your baby being affected by your anxiety.

Also, new parents sometimes mistakenly assume their newborns are nervous because their hands tremble, their chins quiver, and they startle at sudden sounds or movements. However, those reactions are normal signs of a newborn’s undeveloped nervous system and automatically disappear after about three months.

In my experience, however, there are a few ways a mother’s anxiety about her fussy infant could unintentionally nudge her baby into more crying:

However, when you carefully study the issue of maternal anxiety, it’s clear that it can’t be making a million of our babies cry for hours every day. The nervous-mommy theory fails to explain three colic characteristics:

Trina didn’t need to worry that her stress had invaded Tatiana’s tender psyche. In reality, the opposite is usually the case. Your baby’s wail can trigger red alert in your nervous system, making you feel tense and anxious!

During medical school, I was taught colic was an intestinal problem. Soon thereafter, that theory was pushed aside by the concept of brain immaturity. As we discovered more about our babies’ nervous systems, we came to believe colic resulted from their immature brains getting overstimulated by all the new experiences babies encountered after birth. It’s no wonder this theory became popular because, let’s face it, babies are so … immature!

Babies have the coordination of drunken sailors and the quick wits of, well, newborns. But what exactly is immature in your baby’s brain, and how might that predispose him to uncontrollable crying?

Imagine you’re taking a very long trip but can only bring one suitcase with you. Now imagine that your suitcase is tiny. In a funny way, that’s the situation your baby was in as he was preparing for birth. He could only fit into his small brain the most basic abilities he would need to live outside the protection of your womb.

If you could have helped him pack, what abilities would you have considered important for him to be born with? Walking? Smiling? Saying “I love you, Mommy”?

Over millions of years, Mother Nature picked four indispensable survival tools to fit into our babies’ apple-size brains:

1. Life-support controls—the ability to maintain blood pressure, breathing, etc.

2. Reflexes—dozens of important automatic behaviors that help newborns sneeze, suck, swallow, cry, and more.

3. Limited control of muscles and senses—once babies can breathe and eat, these very limited abilities allow them to touch, taste, look around, and interact with the world.

4. State control—after babies start interacting with their families and their exciting new world, state control helps them turn their attention on (to watch and learn) and off (to recover and sleep).

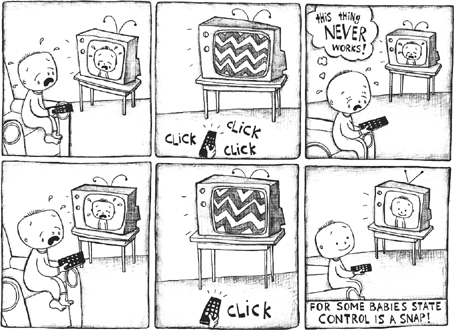

Of all of these abilities, state control is the most important in determining whether or not he gets colic.

When doctors talk about your baby’s state, we’re not discussing whether you live in Ohio or Florida. State describes your baby’s level of wakefulness or sleep—in other words, his state of alertness. States range from deep sleep to light sleep to fussiness to full-out screaming. Right in the middle is perhaps the most magical state of all: quiet alertness. It’s easy to tell when your baby is quietly alert: his eyes will be open and bright and his face peacefully relaxed as he surveys the sights around him.

Maintaining a state is one of the earliest jobs your baby’s brain must accomplish. His ability to stop his crying, keep awake, or stay asleep is called his “state control.” I like to think of state control as your baby’s TV remote, which allows him to “keep a channel on” when something is interesting, to “change channels” when he gets bored, and to shut the “TV” off if it starts upsetting him or it’s time to go to bed.

Many young infants have excellent state control. These “I can do it myself” babies focus intensely on something for a while then pull away whenever they want; they easily shift between sleeping, alertness, and crying. These self-calming babies are especially good at protecting themselves from getting overstimulated. When the world gets too chaotic, some stare into space, some rhythmically suck their lower lip, and others turn their heads as if to say, “You excite me sooo much, I just have to look away to catch my breath!”

You may also notice your baby settling himself by using an attention off-switch called “habituation.” It is one of your baby’s best tools for shielding himself from getting too much stimulation. Like a circuit breaker that cuts the electrical flow when the wires overload, habituation allows your baby to shut off his attention when his brain gets overloaded.

Habituation explains the extraordinary “sleep anywhere-anytime-despite-the-noise” ability that infants have. (It’s also the tool baby boys use to help them sleep despite the pain of circumcision.)

You’ll notice that your newborn follows a simple plan during his first few weeks of life: eating and sleeping! Then, as he acclimates to being out of your womb, he’ll spend increasing time in quiet alertness. Unfortunately, many young babies can’t handle the additional excitement that comes with this alertness. These babies are poor self-calmers with immature state control. They have trouble shutting off their alertness, so their circuits often overload. After a few weeks, as they begin to wake up to the world, their state control starts to get overwhelmed and fail.

These babies look exhausted but their eyes keep staring out, unable to close, as if held open by toothpicks. It’s as if their remote control malfunctioned, stranding them on a channel showing a loud, upsetting movie.

One exasperated mom told me her colicky three-month-old, Owen, cried for several hours every day. He clearly needed to sleep, but he wouldn’t close his eyes. She said, “I keep trying to get him off The Crying Channel and help him find the Sleep Station again.”

When your little baby is locked into screaming, please don’t despair. Much better state control will be coming to rescue you both in a few months. In the meantime, the second part of this book will teach you exactly how to soothe him when he’s having a meltdown.

Avoid overstimulation with toys, lights, and colors; this fatigues the baby’s senses.

Richard Lovell, Essays on Practical Education, 1789

Considering how exciting the world is, it’s a wonder that all babies don’t get overstimulated! Fortunately, most are great at shutting out the world when they need to. However, if your baby has poor state control, even a low activity level may push him into frantic crying. He may begin to sob because of a tiny upset, like a burp or loud noise, but then get so wound up—by his own yelling—that he’s soon raging out of control.

These babies cry because they get overstimulated and then stuck in “cry mode.” If we could translate their shrieks into English, we’d hear something like “Please … help me … the world is too big!”

Your baby is not crying to make you pick him up, but because you put him down in the first place.

Penelope Leach, Your Baby and Child

Our culture believes in the strange myth that a baby wants to be left in a quiet, dark room. But what is this stillness like for your new baby? Imagine you’ve been working in a noisy, hectic office for nine months. One morning you come to work and find yourself alone—no chatter, no ringing phones, no commotion. Soon, the stillness gets on your nerves. You begin pacing and muttering, until you lose it and scream, “Get me out of here!”

This scene is similar to the way babies experience the world when they come home from the hospital. Although our image of the perfect nursery is one where our little angel sleeps in serene quiet, to a newborn that feels a bit like being stuck in a closet.

As strange as it sounds, your baby doesn’t want—or need—peace and quiet. What he yearns for are the pulsating rhythms that constantly surrounded him in his womb world. In fact, the understimulation and stillness of our homes can drive a sensitive newborn every bit as nuts as chaotic overstimulation can.

Does understimulation mean babies cry because they’re bored? No. Unlike older children and adults, babies don’t find monotonous repetition boring. (That’s why your baby is happy drinking milk day after day.) Rather, they find the absence of monotonous repetition hard to tolerate. Their cries ask for a return to the constant, hypnotizing stimulation of the womb. Fussy babies often take three months before they become mature enough to cope with the world without this rhythmic reassurance.

Either understimulation or overstimulation can be terribly unsettling to young infants; however, even worse is to experience both at the same time. When an immature baby is subjected to chaos in the absence of calming, rhythmic sensations, it can drive him past his point of tolerance!

Brain immaturity is a large piece of the colic puzzle. But this theory can’t be the whole truth because it fails to explain two crucial colic clues:

A few years ago, I spoke at a Lamaze class. During the talk, a pregnant woman named Ronnie told the class about her plan to have an “easy” child. She said, “I have two friends with young children. Angela has twin two-year-olds who scream and fight like little savages, but Lateisha’s child is an angel. I don’t want to make the same mistakes Angela did; I want my baby to be like Lateisha’s little princess!”

Anyone who has been lucky enough to spend time around infants knows that some babies are as gentle as a merry-go-round while others are as wild as a roller coaster! What makes some children so volatile and challenging? Was Ronnie right? Is an error committed by their parents, or are some babies just natural-born screamers?

There’s an old story that as a boy handed his father a report card of all F’s, he lowered his head and asked quietly, “Father, do you think my trouble is my heredity … or my upbringing?”

For generations, people have debated what predicts a child’s temperament. Is it determined by his hereditary gifts (nature) or is personality gradually molded by one’s upbringing (nurture)?

A thousand years ago, baby experts believed temperament was transferred to babies in the milk they were fed. That’s why ancient experts warned parents never to give their baby milk from an animal or from a wet nurse with a weak mind, poor scruples, or a crazy family.

Today it is widely accepted that many personality traits are direct genetic hand-me-downs from our parents. For this reason, shy parents usually have shy children, and passionate parents tend to have babies who are little chili peppers.

Andrea was the spirited baby of Zoran, a former race-car driver, and Yelena, a mile-a-minute research psychiatrist. A real handful from the moment she was born, by two months of age Andrea shrieked her complaints almost twenty-four hours a day. As Zoran noted, “She’s as tough as nails, but what else would you expect? Two Dobermans just don’t give birth to a cocker spaniel!”

Let’s take a closer look at temperament and see why, even though it may contribute to colic, it’s not the main cause.

People are wrong when they think that quiet babies are good and fussy babies are bad. The truth is that some gracious and softhearted babies fuss a lot because they can’t handle the turbulence of the world around them.

Renée, mother of Marie-Claire, Esmé, and Didier

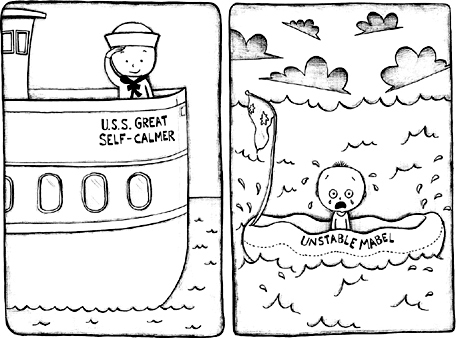

Your baby is like a boat and her temperament the sea she sails on. If her boat is stable (a good self-calming ability), and the sea is smooth (she has a calm temperament), she will sail through infancy. However, if the boat is unstable (a poor self-calming ability), or the sea is rocky (she has a challenging temperament), she’s in danger of getting tossed about. Once children get older and their self-calming ability becomes stable, the turbulence of their passions is no longer such an overpowering experience. But for young babies, a very intense temperament may be more than they can handle.

Luckily, most babies are mild-tempered and easy to calm, like sweet little lambs. But challenging babies are more like a mix of skittish cat and bucking bronco. These excessively sensitive and/or intense babies engage in a daily struggle to keep their balance during their first months of life.

Mild and mellow from the first moments of life, rather than scream at birth, an easy baby might shyly fuss, as if to say, “Please Mummy, it’s a teensy bit too bright in here!”

Sabrina was one such undemanding baby:

Sabrina’s dark lashes framed eyes the color of the sky. She was extremely alert, watching the world with the peaceful gaze of an old Zen master. Sabrina slept beautifully and hardly ever cried. Even when she was hungry, she rarely made a noise louder than a whimper to get her parents’ attention.

Easy-tempered babies have terrific state control and are great self-calmers. They are easygoing little “surfer dudes” who have no trouble taking all the craziness of the world in stride.

However, babies who are very sensitive or intense—or, Heaven help you, both—and who have poor self-calming skills may not be able to keep from screaming as the world’s strange mixture of action and stillness toss them around like boats in a storm.

Lizzy and her twin sister Jennifer were like two peas in a pod, both super-sensitive to noise and sudden movements. When unhappy, their faces flushed and cries flew out of their mouths with deafening force.

However, while Jenny was usually able to quiet her own crying, Lizzy’s screams pulled her like a team of wild horses. Once she got rolling, she had no ability to rein herself in!

Lizzy’s mother, Cheryl, tried to regain control of her frenzied daughter with pacifiers, wrapping, and constant holding, but nothing helped. “For the first three months, I walked around every day not knowing when the ‘train wreck’ would occur.”

Babies like Lizzy are tough. During the first few months of life, their personalities can be too big for them to handle. That’s why parents often dub these babies with funny names to remind themselves not to take life too seriously. For example, Amanda’s parents nicknamed her “Demanda,” Natalie Rose’s parents called her “Fussy Gassy Gussy,” and Lachlan’s parents referred to him as “General Fuss-ter.”

Two types of temperament can be particularly challenging for new parents: sensitive and intense.

Of course, we all know that some people are much more sensitive than others. One person can sleep with the TV on while another is annoyed by any little sound. Some newborns also show signs of being extra sensitive, such as jumping when the telephone rings, grimacing at the taste of lanolin on your nipple, or turning her head to the smell of your breast.

Sensitive babies are wide-eyed and super-alert; their reactions to the world are as transparent and pure as crystal. But like crystal, sensitive infants are often fragile and require extra care. They are so open to everything around them they can easily become overloaded. That’s why these babies have such a hard time settling themselves when they’re left to cry it out. In other words, they can go bonkers from being bonkers!

If your newborn has a sensitive temperament, she may occasionally look away from you during her feeding or playtime. This is called “gaze aversion.” Gaze aversion occurs when you get a little too close to your baby’s eyes. Imagine a ten-foot face suddenly coming right in front of your nose. You, too, might need to look away or pull back a bit and check it out from a more comfortable distance! Don’t mistake this for a sign that she doesn’t like you or want to look at you. Just move back a foot or two and allow her to have slightly more space between her eyes and your face.

Throughout your baby’s normal waking cycles, he’s bound to experience tiny flashes of frustration, annoyance, and discomfort. Calm babies handle these with hardly a fuss, but intense babies handle these intensely. It’s as if the “sparks” of everyday distress fall onto the “dynamite” of their volatile temperament, and “Kapow!” they explode. When babies lose control like that, they may get so carried away that they can’t stop screaming even when they’re given exactly what they want.

This intense crying was what Jackie experienced when she tried to feed her hungry—and passionate—baby. Two-month-old Jeffrey often began his feedings like this:

“He would let out a shriek that sounded like, ‘Feed me or I’m gonna die!’ I would leap off the sofa, take out my breast, and insert it into his cavernous mouth. However, rather than gratefully taking it, he would often shake his head from side to side and wail around my dripping boob as if he were blind and didn’t even know it was there. At times I worried that he thought my breast was a hand trying to silence him rather than my loving attempt to come to his rescue.

“Fortunately, I had already figured out that Jeffrey couldn’t stop himself from reacting that way. So, despite his protests, I kept offering him my breast until he realized what I was trying to do. Eventually, he would latch on and start suckling. And then, lo and behold, he’d eat as if I hadn’t fed him for months.”

Jackie was smart. She realized Jeffrey wasn’t intentionally ignoring her gift of food; he was just a little bitty baby trying to deal with his great big personality. Like a rookie cowboy on a rodeo bull, he was trying so hard to hold on that he didn’t notice she was right there next to him, ready to help.

As babies grow up, they don’t get less intense or sensitive, but they do develop other skills to help themselves control their temperaments and better cope with the world. By three months they begin to smile, coo, roll, grab, and chew. And shortly thereafter they add the extraordinarily effective self-calming techniques of laughter, mouthing objects, and moving about.

What’s Your Baby’s Temperament?

Even on the first days of your baby’s life, you can get glimpses of his budding temperament. The answers to these questions may help you determine if your child’s temperament is more placid or passionate:

1. Do bright lights, wet diapers, or cold air make your baby lightly whimper or full-out scream?

2. When you lay him down on his back, do his arms usually rest serenely at his sides or flail about?

3. Does he startle easily at loud noises and sudden movements?

4. When he’s hungry, does he slowly get fussier and fussier or does he accelerate immediately into strong wailing?

5. When he’s eating, is he like a little wine taster (calmly taking sips) or an all-you-can-eater (slurping the milk down with speedy precision)?

6. Once he works himself into a vigorous cry, how hard is it for you to get his attention? How long does it take to get him to settle back down?

These hints can’t perfectly predict your child’s lifelong temperament, but they can help you begin the exciting journey of getting to know and respect his uniqueness.

With time infants develop enough control over their immature bodies to allow them to direct the same zest that used to spill out into their shrieks into giggles and belly laughs. Passionate infants often turn into kids who are the biggest laughers and most talkative members of the family. (“Hey, Mom, look! Look! It’s incredible!”) And sensitive infants often grow into compassionate and perceptive children. (“No, Mom, it’s not purple. It’s lavender.”)

So if you have a challenging baby, don’t lose heart. These kids often become the sweetest and most enthusiastic children on the block!

Is a baby’s temperament the key factor that pushes him into inconsolable crying? No. This reasonable theory fails because it doesn’t explain three of the universal colic clues:

Goodness of Fit—What happens when two cocker spaniels give birth to a Doberman?

Since temperament is largely an inherited trait, a baby’s personality almost always reflects his parents’. However, just as brown-eyed parents may wind up with a blue-eyed child, mellow parents may unexpectedly give birth to a T. rex baby who makes them run for the hills!

Parents sometimes have difficulty handling a baby whose temperament differs dramatically from their own. They may hold their sensitive baby too roughly or their intense baby too gently. These parents need to learn their baby’s unique temperament and nurture him exactly the way that suits him the best.

So if one million U.S. babies aren’t crying because of gas, acid reflux, maternal anxiety, brain immaturity, or inborn fussiness, what is the true cause of colic? As you will see in the next chapter, the only theory that fully explains the mystery of colic is … the missing fourth trimester.