“Each thing we see hides something else we want to see.”

René Magritte

“The world is moving too fast,” lamented the successful middle-aged stock broker. He had worked hard to achieve his senior status and his corner office, but now he complained, “I just don’t feel I can keep up with all the changes that are happening.” He was having trouble sleeping and getting migraine headaches almost daily. Although they were annoying during the week, they became almost explosive on Saturday mornings, requiring him to stay in bed a good part of each weekend. He gained partial relief by drinking coffee, consuming almost six cups each day. Although his house was paid for, his pension fully funded, and his children’s college funds well stocked, he hadn’t taken a real vacation in over four years.

From a Western perspective, this man was having caffeine-withdrawal headaches, exacerbated by his irregular sleep-wake pattern. From the Ayurvedic point of view this poor man’s life was being ruled by movement without rhythm. The air element (Vayu) had become excessive and was carrying him away. He needed to come back down to earth (Prithivi), and recapture the steadiness, stability, and balance that had always been his character. He needed to remember what he was really made of and return to his true nature.

In every culture throughout history, human beings have speculated as to how the world began, and about the principles that continue to structure and govern it. Our fundamental human interest in the beginning is not just metaphysical. There has always been a sense that, by thinking about how things began, we can understand the powers that are still at work in our daily experience of the world. In ancient times these cosmic speculations were generally quite poetic and metaphorical. A Chinese creation myth, for instance, describes the universe as originating from a gigantic hen’s egg, while a Norse myth refers to a primordial cow emerging from a block of ice. Both these stories imply that animals are vehicles through which supreme powers express themselves, and this veneration of animals manifested itself elsewhere in art, religion, and even in early medicine. The Judeo-Christian tradition describes the beginnings of the universe in more abstract terms, with the disembodied voice of God commanding, “Let there be light.”

Anthropologists debate the extent to which the peoples of the past thought that their myths literally described the process of creation. In the case of the Scandinavian peoples and their story of the “ice cow,” for example, it’s clear that the myth was of primarily symbolic significance, and that its importance was in the psychological and perhaps subconscious connotations evoked by the narrative, not as a depiction of how the universe really began. But now, at the end of the twentieth century, there is no doubt that cosmologists believe the current scientific model of creation is intended to describe “what really happened.” According to the so-called big bang theory, the universe began when an entity of incomprehensible density exploded, generating the matter that makes up the galaxies and propelling it outward at unimaginable speeds. Over time, primordial matter cooled and condensed, resulting in galaxies, stars, and planets. Most cosmologists believe that the universe will continue to expand, doubling its known size over the next ten billion years. Will gravitational forces eventually overcome the expansion of the universe, leading to a contraction back to the center? This concept of an oscillating universe that expands and contracts over eons of time evokes the Vedic image of a breathing cosmos—the exhaling and inhaling of Brahma, the primordial creator. Modern cosmologists continue to debate the ultimate fate of our universe.

Despite some dissenters, the big bang theory is the prevailing explanation of the origin of the cosmos. But although it seems to describe fairly accurately the universe as we perceive it, the theory raises the question of what preceded the cosmic explosion? Where did the original entity come from? How long did it exist before exploding? What caused it suddenly to break apart?

Scientists respond to these inquiries in various ways. To the physicist Stephen Hawking, such questions are very understandable but scientifically naive. Asking what came before the big bang, he has said, is like asking what’s north of the North Pole.1 And yet, great scientists, including Albert Einstein, have not so readily dismissed these questions as they searched for a unified theory that would define the essential “stuff” out of which the universe arose.

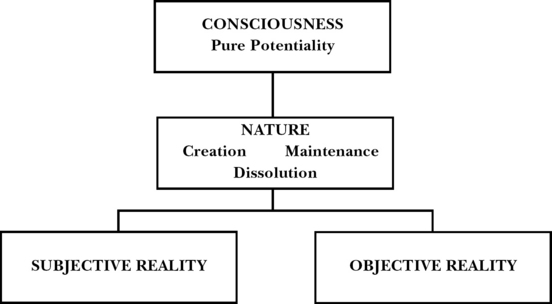

Ayurveda teaches that consciousness is, in effect, the unifying principle that physicists are seeking. Consciousness is the organizing essence of the universe that simultaneously transcends and creates the world we perceive. The essential “stuff” of the universe is actually “non-stuff.” But this essential non-stuff is not the same as emptiness, for within it is contained the potential for all that was, is, and will be. The seen world has its roots in the unseen field of pure potentiality—in consciousness. From this primal consciousness, the elements that make up the universe come into being. Western science has not yet named this unifying essence and might be reluctant to embrace the terms consciousness or pure potentiality. Yet, when we look at the original Ayurvedic term for this primordial state from which the universe arose, the Sanskrit word, avyakta, simply means “unmanifest.” Contained within the unmanifest is the impulse to create, known in Ayurveda as prakruti, or nature. In essence, Ayurveda simply describes the universe as arising from a field of potentiality that has an intrinsic nature to create.

Modern physics also describes the universe—consisting of time, space, and matter—as arising from a timeless, spaceless point. This is the culmination of a long tradition in Western thought. Pre-Socratic philosophers such as Heracleitus asserted the existence of a basic substance from which all things came and to which all things returned. Heracleitus called this primordial essence logos, which is the root word of logic and intelligence. The logos of Heracleitus can be understood as a cosmic governing and generating principle analogous to the primordial consciousness of Ayurveda, and here the Western and Eastern traditions begin to sound very much alike.

The Ayurvedic concept of creation describes not only the beginning of the universe, but also a continuing creative process that is occurring at every moment. Ayurveda teaches that the entire universe unfolds through the interaction of three vital principles, which in Sanskrit are known as the gunas. They are sattva, the creative principle; rajas, the principle of maintenance; and tamas, the principle of destruction. Everything that we perceive through our senses, from elementary particles to galaxies, is born, has a life span, and eventually dies. In this dynamic cycle, the gunas are the principles that are continuously expressing themselves.

According to Vedic philosophy, the three gunas interact to create both subjective and objective realities. In the subjective realm, the five sense organs, five motor organs, and the conscious mind are brought into being. On the objective side, the gunas give rise to five great elements, or mahabhutas, and five subtle elements, or tanmatras, the quanta of perceptual experience that feed our five sense organs. The five great elements are the codes of nature that compose the world of perceived forms.

The mahabhutas are not elements in the sense that Western science most often uses that word, meaning substances that cannot be chemically broken down into constituent parts. Water, for example, is a compound rather than an element. It combines atoms of the elements hydrogen and oxygen. The atomic nuclei of these most fundamental substances all contain the same number of protons. In the Western terminology, this atomic number is the identifying characteristic of an element, and science currently recognizes 109 of them. Textbooks often refer to them as the building blocks of the universe.

To suggest, as Ayurveda does, that the universe is composed of only five elements would seem to be an invitation to ridicule. But here the Ayurvedic viewpoint is actually much closer to the perspective of contemporary physics than to the conventional definition of elements presented in high-school science classes. Quantum physics teaches that the universe is governed by four basic forces: a strong nuclear force, which binds together the particles of atomic nuclei; a weak nuclear force, which controls the process of radioactive decay in heavy atoms such as uranium; an electromagnetic force, which maintains subatomic particles in their orbits around the nucleus; and the force of gravity, which governs the attraction between large objects. Similarly, the Ayurvedic elements are the principles that underlie creation rather than the building blocks that make it up. Though Ayurveda does identify these principles with substances, it would be a mistake to understand this too literally. Charles Steinmetz, the great mathematician and electrical engineer who worked closely with Thomas Edison, believed that electricity was not really a substance like water or wind, but an abstraction, an animating principle behind the “way things happen.” Though he probably never heard of Ayurveda, Steinmetz was really describing electricity as an element in Ayurvedic terms.

CREATING THE UNIVERSE

The Ayurvedic Model

The five great elements are space, air, fire, water, and earth—and here again distinctions between Western and Eastern traditions of natural philosophy begin to blur. Aristotle, for example, taught that the universe was composed of these same five elements and he as well as other Greek philosophers may have been influenced by ideas from India that had reached Greece. A similar theory of the elements was the basis of the medieval science of alchemy, and a variation of this was employed by the brilliant sixteenth-century physician Paracelsus. According to Ayurvedic teaching, the five elements underlie our experience of the material environment. They are the principles structuring the world that is reported by our senses.

Space in Ayurvedic terms is the emptiness in which unlimited potential resides. In this sense, space can be described as the outermost manifestation of the mind, which also encompasses infinite possibilities. Ayurveda teaches that space is the field of unlimited potential from which consciousness creates the material universe.

To understand this, it may be useful to refer to the French philosopher Henri Bergson’s definition of consciousness as choice.2 According to Bergson, people are more conscious than stones because human beings can experience various intentions, make selections among them, and act upon these choices. On the other hand, people are less conscious than God because our choices are not infinite. In Ayurvedic terms, space is the principle of unbounded choice-making potential—and it is literally everywhere, though our senses may deceive us on this point. For example, modern physics asserts that more than 99.99 percent of the material world is actually empty space, despite its apparent solidity. Even subatomic particles are only localized probabilities, and the vast emptiness between the electrons and nucleus of an atom is proportionately far greater than the distances between the planets of our solar system.

From a biological viewpoint, the element of space can be recognized in the membranes, pores, and receptor spaces of every cell in our bodies. If there is any obstruction to these areas, if passage through these spaces is somehow blocked, the cell will not survive. Even in the embryology of a human being, most major development consists of the creation of tubes to enclose and internalize space. As early as the third week of fetal life, cells on the surface of an embryo fold inward to create a groove that eventually forms the brain and nervous system.3 Similarly, primitive cells create tubes that develop into the heart and blood vessels, the gastrointestinal tract, and the respiratory system. This enclosing, but not obstructing, of emptiness, of space, is a characteristic and essential feature of life.

Air represents the principle of movement. Perhaps its presence is implicit in the element of space, for even as we envision a vast, empty expanse, we naturally imagine ourselves moving through it.

Movement is an essential feature of the universe, which is in a constant state of flux at every level. Vast galaxies are hurtling away from one another at unimaginable speeds, electrons are speeding around atomic nuclei, and, somewhere in between, people are driving along freeways in their automobiles. Even when material objects appear to be stationary, there is always activity at a subtler level. A piece of wood may appear to be stable, but the atoms that compose it are in continuous motion.

The human body perceives the element of movement through the sense of touch, through which tactile receptors register subtle fluctuations against the skin. At the microscopic level, this element expresses itself in the exchange of gases that is critical to each cell’s functioning; cellular respiration is a magnificently orchestrated chemical symphony in which oxygen is utilized to extract energy and carbon dioxide is eliminated as a waste product. Movement is also represented by the continuous motion of molecules within and between cells. At every instant, DNA is zipping and unzipping to reveal vital genetic codes, proteins are being transported from their manufacturing plants to important cellular construction sites, and chemical messengers are delivering constantly updated packets of information.

As consciousness increases in density and complexity, the Ayurvedic principle of fire comes into being. Once again, the existence of this element is implied by the existence of the previous one. Thus, fire is inherent in movement, for wherever there is motion there is friction, and friction in turn gives rise to heat and light.

Above all, fire is the transformational principle that changes states of matter from one form to another, and the addition or subtraction of fire reconfigures the atoms that compose a given substance. When fire is applied to a solid such as ice, for example, the solid becomes a liquid—and if fire is then applied to the liquid, it becomes a gas.

In biological systems, the fire principle expresses itself in the conversion of glucose, fats, and protein into energy. This conversion process occurs primarily in the mitochondria, the “energy factories” of the cell. The transformation of the chemical energy of food into the cells and tissues of a living being requires the orderly flow of intelligence through the chaotic field of all possibilities. This controlled production of heat and energy is a critical feature of living systems, which could not survive if the fire element were absent.

Water represents the principle of cohesion and attraction throughout creation. Just as adding water to a bowl of dry flour causes the particles to stick together to form dough, water holds the individual impulses of matter together. Water keeps planets circling around the sun and keeps electrons within the influence of an atomic nucleus. It is also the elemental expression of emotional bonding between people, and as such it underlies the experience of love. Everywhere in nature there is a never-ending contest between the attractive influence of the water element and the freedom-loving impulse toward movement, which is represented by wind. When the cohesive forces dominate, there is an illusion of solidity; when movement dominates, there is an illusion of change.

Life itself originated in the primordial soup of the ocean, and an important aspect of life’s evolution has been the development of efficient ways to internalize the sea. It should be no surprise, then, that human beings are primarily composed of water, which accounts for about 60 percent of our total body weight. In all living things, water is the essential cohesive liquid of the cell, and vital life-supporting functions occur within the cells’ cytoplasm fluid. Quite literally, water is the medium that holds life together.

The earth element represents the material form of creation. As the water element releases energy, atoms approach one another to form objects of mass composed of the earth element. Earth represents all aspects of the material world that are localized in time and space, and it is the most consolidated form of consciousness. As such, it creates the greatest illusion of boundaries. But even the most dense substances—lead, for example—are comprised of atoms, most of which are vast expanses of empty space.

In the human body, the element of earth is represented by the various specific cell components and organelles that maintain independent structure. This includes cell parts such as the nucleus, Golgi apparatus, ribosomes, mitochondria, liposomes, and endoplasmic reticulum. Given the same genetic code and the same blueprint of intelligence, it is a remarkable feature of life that each cell can express its unique talent. Each of these discrete structures has its own reality in time and space, and this reality is an expression of the mass and the structure of the earth element.

Ayurveda presents a fascinating way of describing our perception of the world. Just as we can organize the material universe into the five great elements, we can organize our internalization of the universe through the five subtle elements—sound, touch, sight, taste, and smell. These five subtle elements, or tanmatras, can be thought of as the impulses of experience that matter offers to the sense organs. The Vedic concept is that all matter, which in its essence is condensed consciousness, expresses itself through the subtle elements, which our five senses receive and convert into a mental representation.

The subtlest element is sound, known in Sanskrit as shabda. Sound is the first vibration that stirs from the field of silence. It is perceived to a greater or lesser degree by our organs of hearing, but we know that each living being can only perceive a limited slice of the entire vibratory symphony. The human ear can detect frequencies between fifteen hertz and twenty kilohertz. Dogs can detect vibrations up to fifty kilohertz and certain bats respond to frequencies well above one hundred kilohertz.4 Regardless of the acuity of our hearing organs, sound carries information over distances, small or vast.

The subtle element of touch is known in Sanskrit as sparsha. Our ability to perceive and recognize cutaneous sensations is a feature of the receptors embedded in our skin. We have many types of receptors that respond to a variety of stimuli, including pressure, movement, and temperature. Perception of touch is a function of both the receiving apparatus and our attention. At every moment we filter out billions of bits of information before they enter conscious awareness. For example, you may not be consciously aware of the socks on your feet until reading this sentence, but through the simple act of placing your attention on any part of your body you can activate the sensory impulse that carries tactile information from that region.

The next subtle element is sight, or rupa in Sanskrit. Our ability to perceive electromagnetic radiation with our eyes is a remarkable and complex process. Fundamentally, the human visual system evolved in order to receive the energy of the sun. Although our visual capabilities are truly amazing, allowing us to see a light approximately 1/100,000,000th as strong as bright sunlight, we are still only able to register a small fraction of the visual information that is actually available. We receive visual energy in a relatively narrow band of the entire spectrum ranging from two hundred to seven hundred nanometers, or billionths of a meter.5

Human beings create the rainbow of the world from three basic colors perceived by our retina. Dogs and cats perceive a less brilliantly pigmented environment because they construct hues from only two colors. Some birds use up to five basic colors and may see a world much more brilliant than we could imagine. Insects and some birds and mammals seem capable of seeing ultraviolet light. And, the Australian silvereye bird appears to be capable of detecting magnetic fields through its visual system.6 Although we’d like to think that “seeing is believing,” we only see the narrow vibrations of light that our eyes can capture.

The subtle element of taste is known as rasa in Sanskrit. Taste operates through end organs on the surface of the tongue known as chemoreceptors, because they respond to subtle changes in the chemical environment. This is a critically important capability, because nature has coded information regarding nourishment or toxicity in the form of taste. Western science recognizes four fundamental tastes—sweet, sour, bitter, and salty—but Ayurveda adds two more, pungent and astringent. These last two create changes in the texture of the mucous membranes that provide the mind body physiology with important information on the nature of the substance being tasted.

The last subtle element is that of smell, or gandha. Smell is a primitive sense that allows us to sample the environment at a distance. In order for us to perceive a smell, an object has to release small particles of itself into the wind; moreover, the particles must be soluble in water or fat so they can dissolve in and penetrate the mucous lining of our olfactory receptors. Human beings are capable of perceiving thousands of distinctive odors and fragrances.7 Because of the close relationship between smells and memory, familiar odors often trigger highly emotional associations. The aroma of freshly baked bread, the fragrance of lilacs at dusk, or the scent of rose cologne on the skin of a high-school heartthrob register impressions deep in our memory banks and may trigger cascades of memory when we encounter the smell years after the initial olfactory sensation.

The Vedic sages derived their insights into the nature of reality without benefit of sophisticated scientific instruments. They simply looked inside themselves, and discovered the secrets of the universe within their own physical beings and their consciousness. Their understanding of the world in terms of five great elements is at once simple and profound. Though this perspective is of ancient origin, the concepts are relevant to our current understanding of reality, and can even illuminate our understanding of Western scientific principles. We can, for example, describe chemical reactions as the application of the fire principle, or energy, to systems composed of the earth element, or atoms. This increases the movement principle (the air element) of the atoms, causing a reorganization of bonds (the water element), which results in a new substance.

Similarly, in nuclear reactions a powerful acceleration of the movement principle (the air element) within a system overcomes strong intranuclear bonding (the water element), liberating tremendous amounts of energy (fire) as subatomic particles are released from their bondage.

The theory of the five elements can be applied to human social systems as well. The fast-paced lives we live in the West, which are expressions of the air principle, are disruptive to the social cohesion (water) that bonds members of families, communities, or other organizations that are expressions of the earth principle. The absence of a unifying social fabric results in chaotic releases of emotional energy (fire) that are the bases of the unprecedented levels of violence in our society today.

By beginning to think of the world in terms of space, air, fire, water, and earth, we can gain insight into how the field of pure unmanifest consciousness interacts with itself to create manifest reality. This process is nothing other than the miracle of creation.

Vedic science teaches that we create our own reality. Consciousness, the field of all possibilities, systematically consolidates itself into the material world. The same field of intelligence that structures the galaxies, planets, mountains, and atoms creates living beings. The same intelligence that organizes the solar system, the seasons, and even the migration of birds is the origin of the creative thoughts that arise in our minds. This understanding is eloquently expressed in a Vedic poem:

As is the individual, so is the universe.

As is the human body, so is the cosmic body.

As is the human mind, so is the cosmic mind.

As is the microcosm, so is the macrocosm.