“Whatever notion is firmly held concerning the body, that it becomes.”

Yoga Vasistha, Vedic sage

I am called to the emergency room of my hospital to see Thomas Atkins, a fifty-eight-year-old attorney complaining of trouble speaking and weakness in his right arm and leg for the past day. A self-described meat-and-potatoes man, Mr. Atkins has smoked a package of cigarettes daily since college.

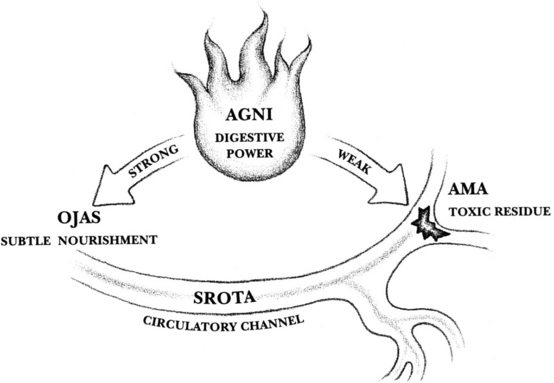

As a neurologist I see that Mr. Atkins has suffered a cerebrovascular “accident” (stroke) due to atherosclerotic blockage in his carotid artery. His high-cholesterol diet and smoking were contributing risk factors. From an Ayurvedic perspective, Mr. Atkins’s Majja dhatu (nerve tissue) was not receiving sufficient ojas (essential nourishment) due to the accumulation of ama (toxic residue) in his pranavaha srota (circulatory channel).

Both interpretations are valid and both lead to therapeutic interventions that are internally consistent, and more often than not, complementary.

You have probably heard your parents or grandparents say, “Nothing is more important than your health,” or “If you have your health, you have everything,” or “Good health is the most valuable thing in the world!” We often hear these exclamations from elderly people who are, unfortunately, no longer able to take good health for granted. If it’s a cliché to say that good health is life’s greatest blessing, as with most clichés there’s a certain truth here. Yet if we ask a number of people what good health really is, the answers will probably be less lyrical than we might expect from a description of the most wonderful thing in the world. “Good health means you feel good,” could probably summarize a majority of the responses—but most people would probably also add some version of the following sentence: “Good health means you ’re not sick.”

This definition of health as the absence of disease is in fact a basic concept of Western medicine. In an earlier chapter, we have discussed how even the most advanced medical facilities are unprepared to devote much time to apparently healthy individuals when there are so many obviously ill patients who need treatment. Yet if we devoted a bit more attention to people when they are symptom-free, they would be much more likely to stay that way. And this would make our entire system of health care more efficient, more affordable, less painful in every way.

In American medical schools, it’s almost a tradition for first-year students to begin their studies by dissecting a cadaver. This practice perfectly expresses the disease-directed orientation of Western medicine. Scrutinizing a dead person, after all, is no way to begin the study of health; rather, it once and for all shifts the focus toward the pathologies and “failures” of the human body, of which death is the ultimate expression. Though this is always left unspoken, the cadaver is actually presented as a kind of murder victim, done in by some as-yet-unidentified viral or oncological or cardiovascular perpetrator—and as any police officer can attest, there’s usually an accompanying sense on the part of investigators that the victim was at least in part to blame for what happened to him. Medical students are almost always irreverent with their cadavers at times, and obviously this is in large part a defensive response. Although every student wonders about the person who once lived in the body laid open in front of them, the purely physical orientation of the gross-anatomy process marginalizes these human concerns. Detachment, cynicism, and arrogance insidiously creep in, widening the gap between the all-knowing doctor and the poor, hapless patient. Perhaps such feelings are inevitable in a system that begins the study of life with a self-contradictory inspection of death. Though dissection of a human body does have clear value in the training of a doctor, it’s interesting to note that the ancient Greek physicians forbade dissection on the grounds that the practice showed disrespect for the human body.

Since its origins, Ayurveda has defined health not as the mere absence of illness, but as the dynamic and balanced integration between body, mind, and spirit. The original intention of Ayurvedic medicine, of course, was to free people from the burdens of ill health in order that they might better fulfill their spiritual potential. Nor was Ayurveda the only ancient tradition that saw a spiritual intention in the practice of medicine and the creation of health. In the fifth century B.C., the Greek physician Herophilus wrote, “When health is absent, wisdom cannot reveal itself, art cannot become manifest, and intelligence cannot be made use of.”

With its understanding of mind and body as a unified whole, Ayurveda teaches that good health is really a higher state of consciousness. Health, then, is much more than just “feeling well” or being free of symptoms. It is a dynamic interplay among the environment, the physical body, the mind, and the spirit—a state in which we open ourselves to entirely new categories of creativity and vitality, including the ability to influence life processes through the power of our own awareness.

Despite all that Western medicine knows about being sick, there is little understanding of how people actually move from health to illness. To illuminate this gray area, Ayurveda begins with the premise that consciousness, rather than biochemistry, is the true source of disease. Specifically, there are two key aspects of awareness that are of supreme importance to health and illness: These are self-referral and object referral.

Object referral is a process of relinquishing the identity of one’s self to some object of reference, which may be an event, a person, or a thing. Once this has taken place—once the self has been exchanged for an external image—we begin to forget the true wholeness of our nature. By identifying ourselves with localized values of awareness, we begin the process that eventually gives rise to disease.

Every day we receive millions of messages from our environment urging us to identify with objects. We are told to buy a more luxurious car, drink a new beverage, own a bigger house, and get a better job, all with the promise that these choices will bring us love, success, and happiness. And we all know the temporary pleasure that these things bring to our lives. Yet most of us also know how material objects fail to provide any lasting sense of value or even importance. In fact, identification with an object that we treasure can actually lead to greater anxiety and discomfort. What if the new car gets dented in a parking lot? What if the diamond ring gets thrown out with the trash? What if my beautiful, sexy lover falls for someone else?

According to Ayurvedic teaching, identifying with anything in the world of name and form is a mistake. It means committing ourselves mentally and emotionally to something that has a beginning, middle, and end—and endings usually bring sorrow and suffering. As mind and body are two fully integrated features of life, any disease in the mind eventually is reflected as disease in the body. Object referral, therefore, is held to be the ultimate source of all illness.

This is a very important point. When remembrance of wholeness is lost, disease begins. Healing is simply the restoration of the memory of wholeness. While it is very useful to understand disease in terms of molecules, bacteria, and viruses, the ultimate cure at all levels of the mind body system depends on restoring the memory of wholeness. This restoration must take place physically, emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually. A fragmented approach cannot be successful or complete. Successful treatment of an illness requires a holistic understanding that includes all aspects of human nature.

In this next section, four key concepts of Ayurveda are introduced: agni, or digestive power; ojas, or subtle life nourishment; ama, or toxic residue; and srota, or circulatory channel. Whenever I present these concepts to Western audiences, I am asked whether they have any substantive objective basis or are best understood as abstract principles. My experience is that they serve best as cornerstones of a theoretical framework to understand health and illness. They are inferred rather than directly observed. I do not anticipate that we will be able to request an “ojas blood level” or perform an “ama biopsy” anytime soon, but these principles are key to improving well being nevertheless.

Ayurveda teaches that good health depends upon our body’s ability to metabolize material received from the environment. This includes not only tangible substances, such as foods and beverages, but also emotions such as anger or fear.

The metabolic power that accomplishes all this is called agni in Sanskrit. Linguistically, agni is the root of the English word ignite, and agni can be thought of as a kind of digestive fire: When it’s robust and powerful, it can take in and metabolize a wide range of materials and use them to advantage. But when agni is weak, even potentially nourishing substances can’t be properly utilized, and toxic by-products may accumulate. Similarly, when flames are roaring in a fireplace, even a damp log will burn down to a fine ash after providing heat and light. But if the fire is weak, the light will be limited, with an abundance of smoke—and if a log is just a little wet, it may put the fire out altogether, leaving a pile of charred remains.

Strong metabolic power allows us to metabolize all our life experiences fully. We can take whatever is nourishing and eliminate whatever is not. The ancient Ayurvedic texts even assert that when digestive power is robust, we can convert poison into nectar—but if digestion is weak, an opposite process will take place. We all know people who seem powerfully capable of processing everything that happens in their lives. They can eat anything, drink anything, and survive all sorts of harrowing personal trials. Of course, other individuals have highly delicate systems and have difficulty metabolizing even simple physical or emotional experiences.

Agni is also responsible for the healthy formation of tissues in the body. If the conversion power of agni is strong, we create healthy blood cells, muscle tissue, bones, and nerves. If agni’s transformative potency is impaired, we create tissues that are weak, fragile, and vulnerable to illness.

It’s easy to understand digestive power in terms of food, but it is important to realize that our minds and hearts are also continuously metabolizing energy and information. If this is the first time you’ve encountered the concept of agni, for example, your mental “digestion” is working right now to break down this new idea into basic components that can be assimilated intellectually. We also have emotional agnis. When these powers are strong, we are able to metabolize emotional experiences efficiently, extracting what is nourishing and eliminating any toxic feelings.

A number of simple but effective steps can be taken to strengthen agni. For example, it is very important that meals are taken in an atmosphere free of distraction or hostility. You may be eating a delicious meal prepared by your beloved, but watching a violent television show at the same time will very likely negate any benefits to his system regardless of the quality of the food. When our awareness is settled, our agnis can focus their energy to create healthy tissues and create ojas, which, according to Ayurvedic teaching, is the true essence of life.

From a Western perspective, agni may be considered in terms of the millions of enzymes responsible for transforming biochemicals into more complex substances. We know that if a specific enzyme is faulty or produced in inadequate amounts due to an inherited or acquired process, illness may result. Someone with alcoholic pancreatitis will not be able to digest his food properly due to a lack of pancreatic enzymes. A child with an inherited muscular dystrophy will not develop normal muscles because he lacks the ability to create an essential protein. Both of these examples can be understood in terms of low metabolic power or weak agni.

This is such a subtle substance that it can actually be considered nonmaterial. Just as light can be a wave or a particle, ojas can be viewed as consciousness or matter, depending upon one’s perspective. It exists at the junction point between mind and body. Vedic tradition states that we are born with a few drops of ojas in our hearts, and that its quantity increases or decreases with each of our thoughts. If our thoughts are of love, compassion, and appreciation, we create more ojas, while resentment, anger, or fear depletes it. When our agnis are healthy, ojas is brought into being at each step of the tissue-forming process. When ojas is plentiful and circulating throughout our system, it provides and strengthens immunity, which in Ayurveda is known as bala, or “strength.” This empowers the mind body system to maintain equilibrium despite any challenges from the environment. So long as ojas permeates our physiology, we cannot be distracted from full awareness of life’s unity. Ojas reminds each cell and tissue in the body that its essential purpose is to support the unity of the whole. When we exhaust all our ojas, our life force is exhausted and we die.

HEALTH AND DISEASE

It is difficult to assign a physical basis to ojas as it vibrates in the boundary between mind and body. Some Vedic scholars have suggested that ojas perhaps represents the basic cholesterol molecule that is the chemical framework for many of our most important hormones, including cortisol, DHEA, estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. Although we have tended to demonize cholesterol in our obsession with coronary heart disease, it is a biochemical that is essential to our survival—in the right amount. Others have suggested that ojas represents some fundamental neuropeptide, such as serotonin or an endorphin. Although I understand efforts to better define what ojas “really” is, I suspect that by its very nature, it cannot be localized to a single chemical.

When our agnis are weak and our metabolic processes are inefficient, Ayurveda teaches that a substance called ama, rather than ojas, is created as a by-product of metabolism. Ama is the Sanskrit term for toxic residue. It pollutes our system and blocks the free flow of information and intelligence. When ama accumulates in the physiology, a sense of dullness, lack of energy, and poor immunity are evident. Individuals with plentiful ama tend to be susceptible to every bacteria and virus. This can foster frequent colds and flu, but eventually more serious illnesses develop. And one also senses that there is not an abundance of happiness in people whose physiologies are dominated by ama. Ama is literally the foundation of disease.

Unfortunately, ama accumulation is almost universal in contemporary Western society, where few of us have consistent access to pure air, pure water, or, for that matter, to people who are pure of heart. This may affect an individual at the level of conscious awareness, but from an Ayurvedic perspective it is clear that negative influences are being introduced into awareness at a subtler level, which will ultimately foster the production of ama. There is a strong argument to be made, for example, that high levels of violence in the media do in fact contribute to the dangerous levels of real violence in our society. In every area of our lives, the more we favor choices that foster peace and purity in our awareness and in our bodies, the healthier we will be.

As our scientific understanding of degenerative illness grows, the concept of ama seems more and more relevant. We now know that illnesses ranging from arthritis to Alzheimer’s disease are in large part the end result of cellular damage inflicted by free radicals. These highly reactive molecules, created through chemical reactions, damage normal cellular constituents. If our cells’ free-radical scavengers are overloaded, we find ourselves with metabolic end products that cannot be eliminated from our tissues, resulting in dysfunction and, ultimately, cell death. In Alzheimer’s disease, for example, a substance called amyloid is produced, which literally pollutes our brain cells, interfering with normal intellectual functions. Even the common “old-age spots” that many people develop on their hands are due to a chemical waste product, lipofuscin, which, once formed, cannot be eliminated. The recognition of the consequences of free-radical damage is very much in alignment with the Ayurvedic concept of ama.

Ayurveda understands the human body, and any other living organism, as fundamentally a network of channels through which biological intelligence flows. The srotas are an important Ayurvedic concept denoting channels of energy and information. When the channels are open and healthy, the life force is able to nourish the cells and tissues. But if the channels are blocked and the tissues are unable to receive nourishment, dysfunction and disease are the result.

There are thirteen major srotas through which the primary biological processes express themselves. Three of these roughly correspond to the respiratory tract, the digestive tract, and the circulatory system, which are responsible for bringing various forms of nourishment into the physiology. There are also seven channels dedicated to transporting the “essences” of the tissues; that is, the full range of energy and information that must come together in order to create a particular tissue category. For example, a “muscle-forming channel” accomplishes the delivery of amino acids to form the primary muscle proteins, together with iron to supply the myoglobin, a complex protein that binds oxygen. Clearly, a tissue-carrying srota can be a very abstract and technical concept. Rather than thinking of these tissue channels as anatomic structures, it may be useful to conceive of them simply as the orderly flow of biological intelligence.

The three remaining srotas carry sweat, feces, and urine out of the body, and any blockage in these channels will of course result in serious illness. Women have two additional srota channels for transporting menstrual flow and breast milk.

On a purely physiological level, Western medicine recognizes that blocks in circulation lead to illness. Urologists spend a good part of their working day relieving obstructions in the urinary tract, either due to swollen prostate glands or stones in the urethras. An ear, nose, and throat doctor understands the problems caused by swollen sinuses, which block the passages that drain mucus from the head and ears. Cardiologists are constantly seeking to identify and remove obstructions in heart vessels. The expansion of this idea to include all conduits for energy and information throughout the mind and body is a relatively small leap.

In considering these circulatory channels, the essential point is quite clear: Health requires the unobstructed flow of energy and intelligence. Any blockage of this flow results in disease.

If a patient approaches a Western physician with a vague sense that something’s wrong, the doctor may order blood tests, an EKG, or an X ray. All of these will probably be normal, and the patient will be told there’s nothing wrong after all. But there is something wrong, of course, if the patient isn’t feeling well.

Western medicine has difficulty addressing the initial stages of illness, before the appearance of manifest symptoms. In contrast, Ayurveda teaches that a disease is already in its later stages by the time it reveals itself at the level of the physical body. Illness first appears not as a sign or symptom, but as an awareness. Similarly, when disease begins to regress, the first changes occur in consciousness. The patient often knows he or she is getting better before the doctor can detect any changes in objective studies. When a patient with pneumococcal pneumonia receives antibiotics, he or she will improve days before there are any changes in the chest X ray, prompting the rule, “Treat the patient, not the X ray.”

Ayurveda recognizes six stages of disease, each of which may continue for some time. The patient’s intuitive awareness of each stage, however, always precedes any measurable or observable change. As you read through the descriptions below, notice how the first three stages of disease occur in the unmanifest field of the physiology, while only the final three stages occur at the material level.

• First Stage—accumulation. As a result of less-than-ideal choices, imbalance begins to accumulate somewhere in the body. The cause of the imbalance can be traced to some toxicity, which may be in the physical environment, in a food, or even in a relationship.

• Second Stage—aggravation. If the accumulation of toxicity progresses, the toxified dosha begins to distort normal functioning in a subtle manner.

• Third Stage—dissemination. At this stage, the imbalance is no longer contained. The patient experiences vague systemic symptoms, such as fatigue or generalized discomfort.

• Fourth Stage—localization. Eventually the toxic imbalance localizes in an area of the physiology where some weakness exists, perhaps due to an old trauma or some inherited tendency.

• Fifth Stage—manifestation. If the process is allowed to progress still further, an obvious dysfunction is revealed, perhaps as a flare-up of single-joint arthritis, an episode of angina, or the early stages of an infection.

• Sixth Stage—disruption. Finally, if efforts to reverse the disease process are not instituted, the stage of disruption is reached, with the arrival of a full-blown illness.

How can we use this portrayal of the progression of illness to understand and treat disease? A young man raised on cheeseburgers and ice cream ignores the occasional indigestion and bloating that he feels after a big meal. According to Ayurveda, he is accumulating toxicity due to poor food choices, which will lead to aggravation— more cholesterol than he can fully metabolize or eliminate. Over the next ten years, he moves to the next step, the dissemination, as land-marked by an elevated serum cholesterol.

Years later, he progresses into the localization phase, in which cholesterol is gradually deposited into his coronary arteries. By his mid-fifties, he shows manifest evidence of illness when he complains to his doctor of occasional chest pains when he mows the lawn. If the process continues, he is suddenly struck with the crushing chest pain of a life-threatening heart attack.

No one would argue that the seeds of illness were planted years before the full-blown expression of the disease. Ayurveda’s major focus is on identifying the origins of illness in the choices we make and taking steps to prevent the inevitable progression that leads to sickness and suffering.

At a deeper level we could ask the question, why do we choose behaviors that are not good for us? Why do we eat foods that may not be good for us, ingest substances that are potentially harmful, or partake in behaviors that are risky? In an earlier chapter, we mentioned the concept of pragyaparadh—the “mistake of the intellect,” the mind’s temptation to create divisions where none exist. According to Ayurveda, forgetting the unified essence of life is a fundamental error from which all human suffering derives. Conversely, reestablishing connection with wholeness results in the melting away of all disease. Object referral is the single phrase with which Ayurveda accounts for the onset of the disease process—and the cure for all illness is expressed as self-referral. Object referral means that we seek fulfillment in things outside ourselves. Whether it is the promise of some intense sensory gratification, working late into the night to make more money, or using drugs to gain peer approval, the sacrifice of our self for our self-image is the seed of all suffering.

All Ayurvedic interventions are ultimately intended to transform object referral into self-referral, and to restore the memory of wholeness. We will always seek gratification in the world around us and we all deserve to have a good job, a safe home, and nourishing relationships. Ayurveda simply says that by themselves, our possessions and positions will not bring us true and lasting happiness. Therefore, for true health, we must seek to discover that aspect of ourselves that is universal. Then we remember that we are not physical beings having occasional spiritual experiences. Ultimately, we are spiritual beings having occasional physical experiences.

Ayurveda is also a very practical science, however, and it recognizes that potential causes of imbalance can exist at the physical level. Blatant abuse of the senses is one example: If you regularly attend heavy-metal concerts, for example, you will probably experience ringing in your ears or even permanent hearing loss. Seasonal changes are also a significant cause of illness, because each season has specific effects on the doshas that must be counterbalanced in order to maintain health. Many people, for example, suffer from frequent colds and congestion during rainy seasons. This is because Kapha has become dominant in the environment; even if a high proportion of Kapha is not usually present in your system, a very moist environment can foster Kapha accumulation, which underlies congestion and coughs. Similarly, sitting on the beach all day in the middle of the summer can create excessive Pitta in the system, which manifests itself as sunburn. Awareness of environmental influences on our mind body physiology is an important premise of Ayurveda, and minor modifications in our daily activity based upon the season are considered to be very important.

Ayurveda also recognizes that sometimes infectious organisms do invade our bodies. Though they were written thousands of years before the invention of the microscope, the ancient Ayurvedic texts describe entities that seem to resemble bacteria and viruses. There are also detailed descriptions of many parasites and the means for treating them. Parasites are usually discussed as the result of unwholesome contact with the senses, such as through improper food preparation. The Ayurvedic emphasis, however, always remains on the immune competence of the host rather than on the power of any invading germ. The soil, one might say, is always more important than the bug.

Illness is the loss of the memory of wholeness, and health is the restoration of this memory. We lose the memory of wholeness when we identify with objects in our environment. When we become dependent upon people, circumstances, positions, or material possessions for our sense of security and well being, we run the substantial risk of losing the comfort when the external sources of satisfaction are unavailable. The only true and lasting source of peace is spirit. When we identify our essential nature with the field of pure potentiality, we are no longer vulnerable to suffering with every challenge we face in everyday life.

The goal of Ayurveda is always to raise the level of health throughout the course of life. Even if a person displays no specific illness, the state of well-being can still be enhanced. If a disease has manifested itself, the imbalance can be eliminated and wholeness restored. Of course, it is always easier and more effective to treat an illness at the earliest possible stage. If we can achieve balance before there is an abnormality on a laboratory test or X ray, we can avoid suffering and reduce the cost of health care as well. Thus, an Ayurvedic approach places premium value on identifying imbalances at early stages rather than waiting for more serious manifestations. We’ve seen how this concept has not been easily accepted by Western medical science. To suggest that chronic stress with its attendant imbalances in digestion, elimination, and sleep patterns can, over time, lead to serious and life-threatening illness is only now becoming part of the prevailing disease paradigm. A growing body of data, however, is concluding that most of the major causes of suffering and illness are the result of lifestyle choices and interpretations.

We in Western society are unique, in that so many of the illnesses plaguing us are the results of life-harming choices made by large segments of our culture. Technology has provided us with the luxury—or the liability—to ignore substantially nature’s rhythms of sleeping, waking, and nourishing ourselves. As many of us have lost connection with the natural forces in our environment, we have simultaneously lost our connection to the natural healing forces within us. Mind body medicine describes how disease has resulted from this loss—and, perhaps more importantly, it also offers ways for us to reestablish our connection to nature in both our inner and outer environments.