12

A Spirited Performance

At once one of the most popular and the most frustrating tasks the puffer crews can be asked to perform is to carry cargos to or from the highly-reputed malt whisky distilleries dotted around Argyll and the Inner Hebrides.

Popular, because a puffer with its hold full of barley for the malting loft, or of oak staves for the cooperage, is a welcome visitor with a badly-needed cargo: and skipper and crew are traditionally treated to a generous dram or two of clear spirit straight from the stills, and with a proof content which make the commercial blends seem like spring water by comparison.

Frustrating, because sometimes puffers are contracted to carry a load of whisky in cask from the remote distilleries to the bottling and blending plants in the upper reaches of the Clyde or in Glasgow itself. The agony of sailing atop a cargo ample enough to guarantee a lifetime of high-jinks, but guarded by Customs Seals and (sometimes) by Customs Officers in person and thus as unattainable as if it had been on the far side of the moon, is a frustration adequate to torture Tantalus himself.

The Vital Spark and her crew were in just that situation one fine summer’s evening as the vessel lay moored alongside the private jetty of one of Islay’s most respected distilleries.

On her arrival that afternoon in ballast the resident Customs Officers had boarded the puffer and all but stripped her from stem to stern.

“What on earth are they daein’?” spluttered an aggrieved Sunny Jim as he was summarily aroused from his comfortable cat-nap in the fo’c’sle and unceremoniously bundled on deck.

“Chust checkin’ on us, Jum,” said the skipper, “to see if we’ve a place somewhere handy for hidin’ a barrel or two. I’m bleck affronted they should even think it of us. The Vital Spark hass something of a reputation in the coastal trade…”

“You can say that again!” boomed a sonorous voice from the echoing depths of the engine-room. “And some reputation it is, tae.”

“Pay no heed to Macphail, Jum,” said the skipper, raising his voice to ensure that that worthy would miss nothing of what he was about to say. “He’s chust embarrassed because wan o’ the Officers found his secret store of novelles under that loose deckboard in the fo’c’sle and called all his colleagues down to have a good laugh at them.”

The engine-room did not respond to that sally.

“And have any puffer crews ever managed to steal something from a cargo of whisky?” asked Sunny Jim.

“I don’t care for your language, Jum,” said the captain. “Not steal, for sure and it wass neffer for selling that any spurits wass taken, but chust for drinking. Liberate would be a better word for it.

“Myself, I don’t think there iss the same imagination in the puffer crews nooadays ass there wass when I wass a young man your age. Not the same spurit of adventure, you micht say. The modern sailors iss timid, chust timid. They’re feared o’ bein’ caught, for a stert: and they’re feared o’ the Customs — not that I exactly blame them for that. Put a man intae a uniform nooadays and he behaves like an enemy sodger, all aggravation and aggression. Time wass when the Customs offeecials would use their mental agility tae ootfox the crews: today they chust come on board like this efternoon and kick the boat to pieces whether they’ve ony reason to or no’. There iss no subtlety left in what aye used to be a chenuine battle of wuts, when whicheffer side won, the ither respected them for it and swore to get even next time roond.

“I mind servin’ ass an apprentice wi’ a skipper caaled Forbes who had his ain boat: a sailin’ gabbert it wass, and him and the mate and me wass the only crew on board her. Wan time we loaded wi’ whusky in casks at Campbeltown and the Customs men came on board and pit their seals all round the hatch covers.

“You’ll understand that these were inspected when we docked at the blenders in Gleska, and if the seals wass tampered wi’ in any way, then it wass the high jump for aal the crew.

“We were hardly oot the harbour when Forbes grabbed me by the lug and pulled me to the fore end of the cargo hatch. Wan o’ the planks in the hatch side-coaming wass a false plank — it had no tongue and groove to it, so it could chust slide oot leavin’ a wee square hole into the cargo hold.

“ ‘In ye go, Peter,’ says Forbes. ‘This iss whit we employed ye for: ye’re the only wan o’ us small enough to get in through there. Tak’ this wi’ ye’ — and he handed me a piece of rubber tubing — ‘and when ye’ve prised the bung frae the top o’ wan o’ the whusky casks, siphon the spurits and pass us oot the end o this tube so we can start filling oor ain barrel up here.’

“I telt him I couldn’t do that, it would be the jyle for me if I did, for sure.

“ ‘It’ll be the jyle for you if ye don’t,’ says he. ‘For ye’re an apprentice disobeyin’ the command of a superior officer on a shup at sea an’ I’ll hae ye up tae the docks polis in Gleska so fast your feet’ll nae touch the ground.’

“And would you believe, Jim, I wass that feared of him I went and did it, though for weeks efter I didna sleep properly for fear the polis were comin’ to get me.

“There was another gabbart, the Amelia Ann, that wass namely among the longshoremen for the quantity of whusky her skipper could liberate on a trup from Islay to Gleska: the Customs men was fair demented for, no matter hoo mony ropes and wax seals they put on the hatchway, there were aye two or three barrels less in Gleska than the manifest showed: but the wax seals wass neffer broken and the ropes wass always whole. The skipper of the Amelia Ann swore blind that there wass a Customs Officer at the loading berth in Islay who simply couldn’t coont, and they’d no way of disproving it for the seals wass aye intact and they could neffer find ony trace of spurits on the boat.

“What none o’ the authorities knew wass that the skipper had a brither that worked at the forge where the brass master seals for the Customs wass made, and the man chust cast wan extra set for his brither. And ass for the disappearing barrels, well, he simply hung them ower the side from what looked chust like an ordinary fender rope, and hauled them back in again when the inspectors had given up and gone home in disgust.

“Of them aal, though, there wass nobody could touch my old friend Hurricane Jeck for sheer agility when it came to liberating a drop of good British spurits.

“I mind fine wance when him and me wass crewin’ on a puffer caaled the Mingulay that belonged tae a Brodick man. Thanks to Jeck she had the duvvle’s own reputation at the distilleries and wi’ the Customs men, and they always swore they’d catch us sooner or later and really put us through the girrs when we came into a distillery pier.

“Wan time we came into a jetty in Islay late one evening ready to load up a cargo of the very best malt spurits in cask the following mornin’.

“Well, they thocht they had the better of Jeck this time. The distillery had already waggoned the casks down to the pier, and they’d put an eight foot high wire and metal-framed fence not chust at the landward end, but right roond the other three sides of it: and they’d two security guards inside it, sittin’ on top of the stacks of casks.

“ ‘Let’s see ye get somethin’ oot o’ that, MacLachlan,’ said the heid Customs man wi’ a smug grin. Jeck said nothin’, but chust shook his head sadly.

“At two o’clock in the mornin’, when the tide was fully out and the Mingulay was dwarfed by the jetty now rising high above her hull, Jeck shook me awake.

“ ‘Come on Peter, let’s get oor share o’ the spurits!’

“ ‘You’re no’ canny, Jeck,’ says I. ‘We’ll get nothin’ here. The spurits iss all fenced in and the guards iss still awake for I can hear them talking.’

“ ‘So much the better,’ says he: ‘the more noise they make, the easier for us.’

“And would you believe it, he produced an empty barrel and a big brace-and-bit. We climbed over the puffer’s bulwarks onto the horizontal trusses on the framework of the jetty and worked the barrel till it wass under wan o’ the gaps between the planks that made up the surface of the pier, right at the very middle of it. Then Jeck used the gap to drill a hole into the base o’ wan o’ the whusky casks from below, and ass the spurits poured oot he caught them in the barrel we’d brought with us.

“It wass much harder to get the full barrel back on board the boat — but we managed it efter a bit o’ a struggle.

“Next morning we loaded the cargo on board in netting slings, the Customs men roped and sealed the hatches tight, and it wass long efter we’d unloaded in Gleska before the empty cask wass discovered. By that time it wass too late to blame anyone, and the Customs people finally decided it must have been liberated by someone at the blenders. They never jaloused that it would have been possible for Jeck and me to do what we did.”

“What I don’t understand,” said Sunny Jim, “is where you got the empty barrel from — and where you hid it on board?”

Para Handy grinned. “Well, Jum, let’s say that we didn’t drink any tea on the way hame from Islay, long trup though it was. We had chust used the Mingulay’s own water-barrel for the chob!”

“Happy days and high-jinks,” said Jim a little despondently. “I wish we could enjoy some o’ that sort of spree these days, but with these foxy Customs men that’s jist a daydream.”

Para Handy stood up from where he’d been sitting, hunched on the corner of the cargo hatch.

He looked round to ensure no unwanted ears were within eavesdropping range.

“What were you planning for supper the night, Jum?” he asked.

“Salt herring, I thocht,” said Sunny Jim.

The captain grimaced.

“No, Jum, for peety’s sake no. Naethin’ salty, whatever you do. Naethin’ to provoke a thirst. And, a word of advice — don’t be tempted to drink ony of oor ain watter.” He nodded towards the wooden waterbreaker lashed to the mast.

Sunny Jim stared in disbelief. “You don’t mean…?”

Para Handy laid a forefinger against the side of his nose. “But how on earth…?” Sunny Jim began.

“Wheesht, Jum,” said the skipper anxiously. “Wheesht. That’s for me to know: and for them neffer to find oot!” And he turned and waved to the three Customs men standing in animated conversation on the quayside.

FACTNOTE

Many puffers called upon to transport whisky really did regard the operation as something of a challenge to their ingenuity and all of the subterfuges described in this tale were actually employed at one time or another by different crews!

There are about 100 whisky distilleries in Scotland today, a far cry from earlier days before rationalisation, take-over and the economies of scale saw mergers and buy-outs which decimated the numbers of individual enterprises. In Para Handy’s time there were more than 20 distilleries in Campbeltown alone!

The majority of whisky is used for blending, with whiskies from a variety of other distilleries, to create the best-known proprietary brands. The blender’s art is the most highly prized of skills, and the secret of the blending processes jealously guarded.

Only a minority of distilleries produce a whisky which will be bottled and marketed as a ‘single’: that is, unblended with the product of other manufacturers. Almost without exception those whiskies which are branded and sold as singles are malt whiskies, distilled from malted barley in copper pot stills, rather than grain whiskies which are the chief ingredient of the blends, made from maize and unmalted barley in a continuous distillation process.

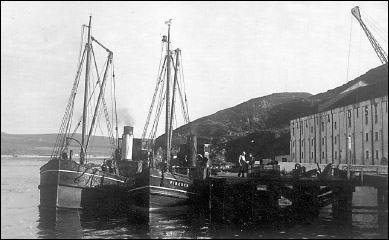

THE AGONY AND THE ECSTASY — Two puffers waiting at the Caol Ila Distillery pier, Islay, for the most frustrating cargo in the world — casks of malt whisky straight from the bond. Though this photograph dates from the 1940s, the agony of proximity to such temptation (and the ecstasy of the generous dram which was the crew’s expected bonus from the manager) were the same then as they had been 40 years previously.

The character and quality of the familiar commercial blends is generally dictated partly by the quantity, but above all by the quality, of the malt whiskies which they contain.

As a rule of thumb, grain whisky is bland but malt whiskies are full-flavoured: most important of all, each malt has its own unique character which the experiment of centuries has proved impossible to duplicate. On Speyside, the major centre of malt whisky production, adjacent distilleries drawing their water from the same river and buying their barley from the same grower will produce totally different whiskies. And nobody knows why.

Some of the finest singles would have been as familiar to Para Handy as they are to the whisky connoisseurs of today — like the world-renowned Islay malts, product of that fertile island lying west of the Kintyre peninsula. They are among the very greatest, the most distinctive (and, for many English or overseas visitors anxious to sample them in public house or off-licence, among the most unpronounceable) names in whisky lore and legend.

Lagavulin. Laphroaig. Bruichladdich. Bunnahabhain.

Names to conjure with!