6

An Inland Voyage

On occasion, the Vital Spark left her familiar Clyde haunts for the sheltered waters of the Forth & Clyde Canal. Sometimes she was bound for the farther shores of the Firth of Forth to load barley for the distilleries back at Campbeltown. Sometimes she would pick up a cargo of timber from the seasoning basins at the port of Grangemouth. Sometimes her business was within the canal network itself, taking coals to the Carron foundries or uplifting pig-iron from Bonnybridge.

Whatever the reasons for her presence on the canal, Para Handy viewed such journeys with an unremitting and quite remorseless loathing.

The other members of the puffer’s crew looked on these inland voyages as a welcome relief from the more demanding environment of the open waters of the Firth, and the associated problems of wind and tide. To chug effortlessly through the countryside along a smooth ribbon of never-ruffled water was sheer paradise compared with the purgatory of battering round Ardnamurchan in the teeth of a howling headwind and a steely, rolling swell.

For the skipper, though, the canal was hell: for here, in every town and village through which the little vessel passed, he was at the mercy of the unfeeling urchins who watched the approach and greeted the passage of the puffer with undisguised derision.

At least on the river and in the firth the sarcastic cries of “Aquitania ahoy!” from boys fishing from piers or hanging over the stern of the crack paddlers shooting past the lumbering puffer could be ignored. The puffer would eventually be out of earshot of the piers, and the paddlers would much sooner be just a dot on the distant horizon as they sped away, carrying his tormentors with them.

On the canal the taunts were ever-present. The Vital Spark was easily outpaced by the ragamuffins of Avondale or Twechar, who assembled on the banks in droves as she approached and then ran alongside her with their merciless, mocking cries as she wheezed her way towards the next set of locks. Her looks and her speed were compared unfavourably with the elegance and pace of renowned passenger-vessels like the Faery Queen or the May Queen and Para Handy could only escape the verbal onslaught by retiring to the wheelhouse, tightly shutting door and windows however hot the weather, and feigning a lofty disdain that he certainly did not feel.

“Man, Dougie,” he would protest, as he watched the gang race ahead and line up at the parapet of the next bridge the puffer must pass under, “ye wud think their faithers and mithers wud bring them up wi’ some sense of the dignity o’ the sea! They’ve no more respect for the Vital Spark than if she wass a common coal scow or a cattle barge!”

Thus a fine May morning found the captain in a foul mood as the puffer approached Camelon on the Forth and Clyde Canal, their destination the Rosebank Distillery on the outskirts of Falkirk with a cargo of the best Fife barley. Her progress through the locks at Grangemouth had involved running the usual gauntlet of taunt and insult and the skipper’s patience was exhausted.

The Vital Spark nosed in to the quayside at the Rosebank basin where two horse-drawn drays stood waiting to start carting the sacks of grain to the adjacent distillery warehouse.

Para Handy, once the unloading had started to the accompaniment of the noisily hissing clatter of the puffer’s temperamental steam-winch, made tracks for the distillery office to report his arrival.

“You’re looking a bit out of sorts today, Peter”, commented the manager, who was well acquainted with the skipper and his crew over many years.

Para Handy explained the reasons for his ill-temper and, to his surprise, found he had a sympathetic ear.

“I know exactly what you mean,” said the manager. “We have just exactly the same problems with the little terrors. Thirty years I’ve been here, and 30 years of splendid service we’ve had from generations of our Clydesdales. But now these new-fangled motor wagons are all the rage, honest horses aren’t good enough for the kids of Camelon.

“ ‘Peep, peep! Oot o’ the way!’ or ‘Can ye no’ get them oot o’ first gear then, mister?’ are the least of the insults my men have to put up with when they’re out on the roads with the drays.”

“No respect, chust no respect at aal,” agreed Para Handy. “It’s a peety we couldna gi’e them a lesson they’d remember, a lesson to shut them up next time they felt like givin’ lip to their elders and betters.”

“Dreams, dreams, Peter,” said the manager and, reaching into a drawer of his desk, produced a square bottle of the colourless straight-from-the-still whisky and poured them both a generous dram.

Unloading the barley sacks took till late afternoon, and so the Vital Spark lay overnight at the Rosebank basin. As the crew were preparing for an early start the following morning Para Handy was surprised to see the distillery manager come running up. Behind him, two workmen were pushing along the towpath a strange-looking machine mounted on four small wheels.

“Could you do me a wee kindness, Peter? Could you put this fire engine off at our Maryhill bottling plant for me?”

Half-an-hour later the puffer cast off and headed towards Lock 16, junction with the Union Canal to Edinburgh, on her journey westwards to Glasgow and the Clyde.

Macphail the engineer was of course the only man aboard able to even begin to comprehend the workings of the machine which now perched on the hatch of the puffer’s empty hold. Leaving his engines to their own devices he prowled round the little contraption, cap in hand, scratching his balding pate.

“Two horse-power,” he read aloud the inscription on the brass plate riveted to the platform on which the device was mounted. “Two horse-power fire pump.”

“Whit does it dae, Dan?” queried Sunny Jim.

“Ah’ve read aboot them,” said the engineer. “It’s wan o’ they new-fangled petrol injins the same as they hae on caurs, but this wan’s for pumpin’ watter.” He gesticulated to the hoses coiled round drums on opposite sides of the frame. “It’s tae pit oot fires. Ye stick the end o’ wan o’ they hoses intae the watter, caw that haundle on the end tae get the injin sterted, and point the ither hose at the flames. The watter gets pumped up and the fire gaes oot.”

“Man, man,” said Para Handy in some surprise. “An infernal machine, my Chove! Whateffer will they think of next?” And he resumed his contemplation of the spring countryside as it slipped by at the rate of 4 knots.

They had a peaceful passage across the central heartland of the Forth and Clyde valley but the canal urchins appeared again as they approached Kirkintilloch.

“Would you look at that,” cried the exasperated skipper as a gang of young boys raced along the towpath beside them, pulling faces and catcalling, “a skelp behind the lug’s what they’re sair in need o’.” And he pulled up the sliding windows to shut himself into the cramped wheelhouse.

The door opened and Sunny Jim squeezed in.

“Captain,” he said, “I’ve got an idea…”

Five minutes later the puffer glided into the Townhead locks in Kirkintilloch. Sunny Jim jumped for the iron ladder let into the stone walls of the lock and climbed to the towpath. Pushing his way through the assembled crowd of young boys he helped the lock-keeper to swing the wooden gates shut at the stern of the boat. The lock-keeper opened the sluice in the gates above the puffer’s bow, and water started to pour into the lock to lift the little vessel up to the level of the next stretch of the canal.

Jim peered down onto the deck of the puffer 10 feet below him. There was surprising activity taking place on the hatchway.

The mate was uncoiling one of the water hoses on Para Handy’s “infernal machine” and Macphail was preparing to swing the iron starting-handle. The skipper himself, with a suspicious glint in his eye, was cradling the brass nozzle at the end of the second hose in his hands.

The puffer continued to rise up the surrounding lock walls as the water flooded in from the higher level. Rows of grinning faces to either side awaited her coming as the Kirkintilloch urchins prepared to subject the hapless Para Handy to another torrent of abuse.

Sunny Jim had a quick, whispered consultation with the keeper as the level of the water in the lock rose higher. That worthy quickly took shelter in his nearby hut, and Sunny Jim, with a last check of the levels, jumped six feet down onto the puffer’s deck and shouted: “Now!”

Macphail swung the starting-handle, the little petrol engine fired, the water pump got down to business, and in a matter of seconds a powerful jet of water shot from the brass nozzle in Para Handy’s grip.

With a whoop of triumph, he directed the jet to left and right, sweeping it across the ranks of his tormentors who, caught totally by surprise, were quickly drenched through before they hesitated, broke, and fled in disarray.

“Let that be a lesson to you,” called Para Handy with a grin of triumph. “Two horse-power and an auld man, that’s aal it takes to send you packing! Maybe next time ye’ll think twice before you give any lip to the men who run the horses and puffers on this canal, eh?”

And, turning the pump off as the lock gates ahead of him swung open and Macphail headed for the engine-room to put some way on the little vessel, he returned to the wheel-house and began to rehearse the very satisfying story he’d have for the manager of the Rosebank distillery next time they met.

FACTNOTE

Only two of Scotland’s canals — the Crinan and the Caledonian — remain fully navigable today, though some stretches of the Forth and Clyde, and Union, Canals have been restored and there are some pleasure sailing opportunities.

The Crinan and the Caledonian remain in use because they still fulfil the purpose for which they were built — to offer an alternative, for smaller vessels, to what would otherwise be a long and exposed sea-passage. Scotland’s other major canals had provided for the convenient transportation of raw materials in bulk, such as timber, steel or coal: and the speedy and more comfortable movement of passengers.

Since both these functions were, in the course of time, better catered for by the railways and the road networks, the canals became outmoded and eventually abandoned. Thus were lost the Forth and Clyde Canal from Grangemouth to Bowling: the Union Canal which (across beautiful countryside and over some quite spectacular aqueducts) linked the centre of Edinburgh to the Forth and Clyde Canal near Falkirk: the Monkland Canal from Glasgow to the coalfields of Lanarkshire: the Paisley Canal from Glasgow to Johnstone, all that was ever completed of an ambitious project to link Glasgow by canal to Ardrossan on the Ayrshire coast: and the less-well-known Aberdeenshire Canal which ran from the Granite City northwards to Inverurie.

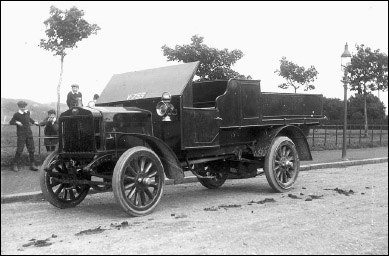

THE NEW HORSEPOWER — Here is the precursor of the juggernauts of today, an early brewer’s lorry with, perched on the fence, some of the urchins whose taunts on and off the Firth could make life such a misery for the beleaguered Para Handy. But it would be 50 years before the last horse-and-cart disappeared from the streets of Glasgow.

At the height of the canal ‘boom’ there were proposals for many other, smaller scale, projects throughout Scotland from the Solway in the south and as far north as the Moray Firth. Some of these, such as a two-mile cut to carry coal from the Ayrshire mines to Saltcoats harbour: a three-mile waterway, again to carry coals, across the Mull of Kintyre from the Machrihanish mines to Campbeltown: and a two-mile canal at Cupar in Fife, to convey limestone, were actually completed.

Two hugely ambitious projects came to nothing: but it is quite intriguing to speculate how the economic history of the country might have been altered if they had. One, first mooted at the beginning of the nineteenth century, proposed a cross-Scotland canal linking Dumbarton on the Clyde with Stonehaven, south of Aberdeen, by way of Stirling and Perth. The second, which was actively promoted for over 60 years and only finally buried for good in 1947, was for a canal linking the Firths of the Forth and the Clyde, a through route for ocean-going vessels, a huge waterway which would have been on the same scale as the Manchester Ship Canal in England. Several alternatives were considered: by far the most dramatic, not to say controversial proposal, would have taken the waterway from the head of Loch Long and through Loch Lomond to debouch into the Forth near the village of Fallin a mile or two east of Stirling.