Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

The gangster picture continued to develop in the 1960s and 1970s, after the success of The Big Heat in the 1950s. The contrast between crime movies set in the city and those set in the country began to emerge. This distinction served to define the difference between urban criminals and rural criminals. When Robert Warshow stated in “The Gangster as Tragic Hero” that gangsters belonged to the city, one wondered what he would have made of Bonnie and Clyde, which clearly portrayed rural criminals. “Arthur Penn’s flamboyant, affecting, and ultimately tragic saga of a pair of Depression-era gangsters” set new standards for on-screen violence.1

At the time when Lang made You Only Live Once, his fictionalized version of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow (see chapter 8), Sylvia Sidney recalled that the “papers were full of them, with that famous picture of Bonnie with her foot on the running board of the car, holding a tommy gun and smoking a cigar.”2 Penn’s much more realistic and authentic film would bring Bonnie and Clyde back to the public’s attention.

When the movie premiered in August 1967, it was a resounding failure. “Warren Beatty came under fire for Bonnie and Clyde,” for which he was both producer and star, “because it was considered sensationalistic and was pilloried for glamorizing violence.”3 Beatty contended that the movie failed because Warner Bros. gave it a limited release due to the fact that Jack Warner had expressed great dissatisfaction with it.

Still, Jack Warner was on the verge of retirement as studio chief, so, at Beatty’s behest, Warner took the unprecedented step of relaunching the movie two months later with a fresh ad campaign. Beatty was convinced that although the picture had gotten some hostile reviews, it had been embraced by younger moviegoers who resonated with Bonnie and Clyde’s antiauthority, antiestablishment views. In fact, Penn’s movie had helped to identify a previously untapped market of young people who were fed up with the “beach party movies” that the studios had been feeding them in recent years, and who gravitated toward the youthful counterculture, of which Warner’s own Rebel without a Cause (1955) was a harbinger. Furthermore, the movie reaffirmed the image of the gangster as a “heroic loner,” an image that had flourished in the gangster pictures of the 1930s, starring James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson.4

The original screenplay for Bonnie and Clyde was the work of two neophyte scriptwriters, David Newman and Robert Benton. (Benton would later write and direct his own screenplays, e.g., Places in the Heart.) Beatty got Arthur Penn to direct the picture because he had already collaborated with Penn on a crime drama, Mickey One (1965). Penn asked for some changes in the screenplay. “We weren’t making a documentary,” he explained; “to some extent we did romanticize the main characters, but so, inevitably, does any storyteller.”5 The screenwriters went with the Barrow family’s image of Clyde as a charming young man who possessed little respect for the law and felt justified in pulling the trigger whenever he felt cornered. He idolized Jesse James and convinced himself and Bonnie that they were champions of the poor and downtrodden during the Depression. By the same token, “they were regarded as folk heroes by many people,” said Penn, even though they killed at least sixteen people, half of whom were law enforcement officers. Penn was dramatizing their legend, what he called the “mythic aspect of their lives.”6

The historical Clyde Barrow, by all accounts, was homosexual, but Penn prevailed on the scriptwriters to make him impotent, a problem that would not complicate Clyde’s relationship with Bonnie as much as homosexuality would. (In real life, they apparently had a young man with them that was bisexual and “serviced” both Bonnie and Clyde, or so it was rumored.) The young man, who is a member of their gang in the movie, is straight: C. W. Moss, as he is called in the script, is a combination of two young men who were members of the gang, which helped to simplify the plot. Their real names were William Daniel Jones and Henry Methvin (whose father eventually betrayed Bonnie and Clyde to the police).

Beatty originally wanted Shirley MacLaine, his sister, to play Bonnie, but he finally settled on Faye Dunaway, who was not a movie star when she took the part. But costume designer Theodora Van Runkle (The Godfather: Part II) catapulted her to fame by designing clothes for her that had the “retro” look of 1930s fashions, topped off by a rakish beret that became a fad with younger women.

Another member of the creative team was director of photography Burnett Guffey (From Here to Eternity). With a minimum of light, Guffey was adept at conjuring up a “naturalistic, gritty look, to complement hard-boiled stories of criminals.”7 When the front office at Warner Bros. complained loudly that some scenes in Bonnie and Clyde were too dark, Guffey was offended and walked off the picture for a week in protest, but he came back and finished the picture and went on to win an Academy Award for his cinematography in the film.

Guffey’s filming of the family reunion, when Bonnie and Clyde visit her mama and kinfolk, is masterful. Bonnie’s interchange with her mother recalls that of Baby Face Martin (Humphrey Bogart) and his mother (Marjorie Main) in Dead End (see chapter 4). Penn told Guffey that he wanted the family scene to have a soft-focused look, and Guffey obliged by putting a piece of window screen over the camera lens to achieve a gauzy, nostalgic effect.

“The editing of this movie,” writes Kael in her extended review of the film, “is the best editing in an American movie in a long time.”8 The editor, Dede Allen, combined a classical Hollywood editing style with more modern techniques, for instance, the jump cut, “giving the film a jagged, menacing quality.”9 There is, for example, the quick look of panic that Bonnie and Clyde exchange just before the Texas Rangers ambush them. Allen would continue to collaborate with Penn after the present movie.

A revised Motion Picture Production Code was promulgated by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), replacing the original code of 1930, on September 20, 1966. It was designed to “keep in harmony with the mores, culture, moral sense, and expectations of our society.”10 As a result, movies like Bonnie and Clyde could receive the seal of approval, which would have been unlikely under the previous code.

The opening credits feature actual family snapshots of Bonnie and Clyde taken before they met. This forecasts what the film proper will take up after the credits, with their first meeting: Looking through her bedroom window, Bonnie Parker spies a young man endeavoring to break into her mother’s automobile. She rushes down to the sidewalk and confronts one Clyde Barrow, who contends that her assumption that he was attempting to steal her mother’s Tin Lizzie was all a misunderstanding. He introduces himself as a former convict and proficient thief. He shows off his gun, which serves as a phallic symbol. She fondles his weapon and says, “I’ll bet you’re not man enough to use it,” thereby prefiguring the scene in which she will discover that he is impotent. Clyde demonstrates his abilities as a thief by holding up a nearby grocery store and stealing a getaway car for good measure. He then invites her to join him in a life of unpredictable adventure.

While engaging in target practice in the front yard of a ramshackle house, a farmer and his family drive up in a truck weighed down with all their worldly possessions; they want to take a last look at their farm, which has been repossessed by the bank. As a gesture of sympathy, Clyde puts a bullet in the bank’s foreclosure sign. As the farmer and his family are about to leave, Clyde suddenly boasts, “We rob banks!” Comments Leland Poague, “He hasn’t robbed one yet, but he’s committed to trying.”11

Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty as gangster lovers in Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Penn injects humor into the film at times to offset the violence. While Clyde is holding up a grocery store to get a supply of food, the manager attacks him with a meat cleaver. Clyde runs out the door, shouting at Bonnie, “Try to get something to eat and the sonofabitch comes at you with a meat cleaver! I didn’t want to hurt him!”

While getting gas at a run-down gas station, they recruit C. W. Moss (Michael J. Pollard), the attendant, to be their driver and mechanic. He is a graduate of a reform school and does not hesitate to join up with gangsters to continue his life of crime.

When the gang is escaping from a bank they just robbed, the bank manager recklessly jumps on the running board of their car. Clyde, caught off guard, fires his pistol at the man’s face, putting out his eye, thereby spraying the car window with blood. At that moment, we realize, Bonnie and Clyde are no longer “adventurers,” but full-fledged gangsters playing for keeps.

Clyde’s older brother Buck (Gene Hackman, in a terrific performance) and his flighty wife Blanche (Estelle Parsons) join the Barrow gang. Bonnie objects, but Clyde insists that they are family. The importance of family seems to mean as much to these impecunious hillbillies as it does to the Mafia. At any rate, the Barrow gang captures a Texas Ranger, Frank Hamer (Denver Pyle). Bonnie suggests that they make him pose for a photo with all of them, “looking as friendly as pie,” and then send the snapshot to the press. The taciturn Hamer appears to be deeply offended by being forced to pose with gangsters, and one surmises that he will not rest until he gets even with Bonnie and Clyde to salvage his professional standing as a law enforcement officer.

For his part, Clyde is chagrined when the papers print spurious accounts of the Barrow gang reportedly carrying out robberies in Illinois, Indiana, and New Mexico—states they have never been to.

During their next bank robbery, Clyde asks a customer, “Is that your money or the bank’s?” He replies that it is his; Clyde responds, “You keep it then.” This brief encounter shows how Bonnie and Clyde encourage their public image as Robin Hoods who rob the rich to give to the poor. Obviously they rob the rich, but they seldom give any of what they steal to the poor. They scoop up their take from a bank robbery and pile into their getaway car, which is a Tin Lizzie. Then they take off down a dusty country road to the tune of Flatt and Scruggs’s exuberant banjo plunking, which makes the policemen, who are in hot pursuit in their jalopy, seem like Keystone Kops.

Bonnie insists that she visit her mama one last time, so the gang arranges for a family picnic with the Parkers. Clyde reassures Bonnie’s mother that he and Bonnie intend to give up their lawless ways “when hard times is over.” Mrs. Parker throws cold water on Clyde’s fancies by saying, “You’d best keep runnin’, Clyde Barrow; and you know it.”

In one of the Barrow gang’s last skirmishes with the law, Buck is slain when half of his head is blown away, while Blanche is wounded and captured, and consigned to the local prison hospital. Bonnie composes a doggerel ballad, which she reads to Clyde before mailing it to the newspapers. Its conclusion actually foretells their end:

Someday they’ll go down together,

They’ll bury them side by side.

To a few it’ll be grief,

To the law a relief;

But it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.

Clyde murmurs when he hears the ballad, “You have made me somebody they’re gonna remember.” The pair begins to make love, and succeed, as Clyde’s impotence has evaporated. Their mutual relationship is the only thing they have left to cling to in life.

Meanwhile, C. W. Moss’s father cuts a deal with Texas Ranger Hamer, whereby he will betray Bonnie and Clyde to the law, in exchange for amnesty for his son. Hamer sets up an ambush on a rural road near Arcadia, Louisiana, on May 23, 1934. Thus writes Peter Biskind in his 2010 obituary of Arthur Penn, “The violent, shocking, and justly celebrated fusillade of gunfire that ends the saga of the outlaw couple, sending them into a slow motion dance of death, was all Penn. It was a visual tour de force executed with four cameras running at different speeds.”12 The ballet of bullets, which seems to go on for an eternity, actually lasts only thirty-five seconds, but it sweeps Bonnie and Clyde into the everlasting realm of legend.

Bonnie and Clyde garnered a passel of mixed reviews when it premiered in the summer of 1967. Bosley Crowther, who maligns the picture as a cheap piece of filmmaking in the New York Times, was, in due course, kicked upstairs by the Times for being out of touch with contemporary tastes. Newsweek critic Joseph Morgenstern vilified the movie in his original review, which he recanted in a follow-up notice. Time magazine’s Jay Cocks excoriated the movie in his review, which he then had to withdraw when the picture became the subject of a Time cover story. The article calls the film a “cultural phenomenon,” whose chief characters America’s alienated younger generation could identify with. To top the critical about-face that marked the picture’s opening, Pauline Kael’s lengthy New Yorker defense of the film came along in October, when the movie was relaunched.

But perhaps the biggest surprise among the picture’s defenders was the endorsement from the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures (NCOMP), formerly the Catholic Legion of Decency, a name the organization shed in 1965, because it smacked of vigilantism. In February 1968, NCOMP held its annual prize-giving ceremony in New York City. NCOMP accorded Bonnie and Clyde its citation as the most highly recommended motion picture of 1967. I attended the ceremony, as did the picture’s producer, Warren Beatty, and its director, Arthur Penn. Penn told me that he was delighted that NCOMP recognized that Bonnie and Clyde was designed to be a thought-provoking work of art and not just a lurid gangster flick.

Anthony Schillaci, an NCOMP consulter, wrote of Bonnie and Clyde, “The banality of their evil, compounded of boredom and meaningless lives . . . and the social disorder of the Depression, makes Bonnie and Clyde tragic folk heroes with whom we can identify.”13 Bonnie and Clyde won Oscars for Estelle Parsons and Burnett Guffey. It also solidified Arthur Penn’s reputation as a major film director. As Jack Shadoian puts it, “Bonnie and Clyde is one of the most important and popular films of the 1960s.”14

Bonnie and Clyde was released at a time when a string of pseudohistorical biographies of gangsters was coming out of Hollywood, from Joseph Newman’s King of the Roaring Twenties: The Story of Arnold Rothstein (1961) to Robert Benton’s Billy Bathgate (1991), with Dustin Hoffman as Dutch Schultz. Al Capone had surfaced in several gangster films, from a fictionalized version of him in Little Caesar and Key Largo to Richard Wilson’s more factual biopic, Al Capone (1959), with Rod Steiger as “Scarface” Al Capone (Capone earned the nickname when he was slashed on the face during a knife fight as a kid). The best picture in which Capone figured was Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables.

The Untouchables (1987)

Alphonse Capone was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1899—not in Italy, as some other Mafia mobsters were.15 He moved to Chicago after a misspent youth as a petty crook. He eventually became the undisputed head of the Chicago Syndicate after he had seven members of his gang, dressed as cops, eliminate several rival mobsters in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929. He was convicted of tax evasion in October 1932, and sentenced to a prison term at Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay. He was released in January 1939, because he was suffering from a case of advanced syphilis that afflicted his brain, as well as other organs.

The TV series The Untouchables (1957–1963) stars Robert Stack as Eliot Ness, the federal agent who was charged with bringing down Capone. The series was derived from Ness’s biography, which was written by journalist Oscar Fraley, with Ness’s cooperation. The series went well beyond the Ness biography to present fictional material needed to fill out six seasons. Thus, in some of the episodes, Ness tangles with the likes of “Legs” Diamond, a gangster he never clashed with in real life. Still, the narration is delivered by newspaper columnist Walter Winchell, whose machine-gun delivery makes the episodes seem like the Gospel truth, when some of them are not.

Capone is dispatched to Alcatraz early in the first season. Hence, Frank Nitti (Bruce Gordon) is Ness’s adversary in most of the episodes, since Nitti took over the management of Capone’s criminal activities when Capone went to prison. (Nitti is killed by Ness during the course of the 1987 movie The Untouchables, which also mixes some fiction with fact.)

The two-hour pilot of The Untouchables was released as a feature film in 1962, entitled The Scarface Mob, with Neville Brand as Capone. Because of the popularity of the TV series, to which Paramount owned the rights, the studio decided to make a feature film with the same title as the TV series in 1987. Producer Art Linson commissioned Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright and screenwriter David Mamet, who wrote the script for the Paul Newman vehicle The Verdict (1982). Mamet fashioned the screenplay of The Untouchables as the story of a federal agent who comes to town and meets a policeman, Jimmy Malone. The veteran cop teaches him some tricks about police work, specifically how to get Capone.

Brian De Palma, the film’s director, was known for his ingenious thrillers, one example being Dressed to Kill (1980), and The Untouchables is a superior crime movie. Kevin Costner’s career-making performance as dedicated lawman Eliot Ness is buttressed by Sean Connery’s portrayal of Jimmy Malone, one of Chicago’s honest Irish cops. Robert De Niro gained thirty pounds to enact the role of Al Capone. Although De Niro is only in a few scenes, he dominates every one of them by his menacing demeanor. “The well-dressed sociopath’s capacity for murderous bloodshed is always there.”16

The picture ends with the customary statement that the characters are “purely fictitious,” and not based on real people, living or dead. That is a curious statement about a film in which, for a start, Eliot Ness, Al Capone, and Frank Nitti appear with their real names. Moreover, accountant Oscar Wallace is based on Frank Wilson, the real-life accountant who provided the documentation that enabled Ness to convict Capone of tax evasion.

Pointing up Patrizia von Brandenstein’s production design in his review of the movie, Roger Ebert writes, “There’s a shot of the canyon of La Salle Street, all decked out with 1920s cars and extras, that’s sensational. And a lot of nice touches like Capone’s hotel headquarters.”17 The exterior of the Lexington Hotel, where Capone lives, was actually the façade of a venerable building at Roosevelt University in downtown Chicago. First-class cinematographer Stephen Burum, who photographed Francis Ford Coppola’s Rumble Fish (1983) in black-and-white, wanted to film The Untouchables in black-and-white as well, but the studio would not hear of it.

De Palma chose Ennio Morricone to compose the background score. Morricone’s reputation had been built on scoring such “spaghetti westerns” as A Fistful of Dollars (1964) in his native Italy. The indefatigable Morricone tried out several possible themes for the opening credits of The Untouchables, with pulsating rhythms, before he was satisfied. His imaginative background music matches the violence, emotions, and dark humor of the film.

De Palma’s picture begins with a printed prologue: “1930. Prohibition had transformed Chicago into a city at war. Rival gangs competed for control of the city’s illegal alcohol. . . . It is the time of gangsters like Al Capone.” In the first scene, we see Capone holding court in his hotel suite while he dishes out clichés to reporters: “You will get farther with a kind word and a gun than with a kind word alone.” He continues, “People are gonna drink. In making liquor available to the public, I am respecting the will of the people.”

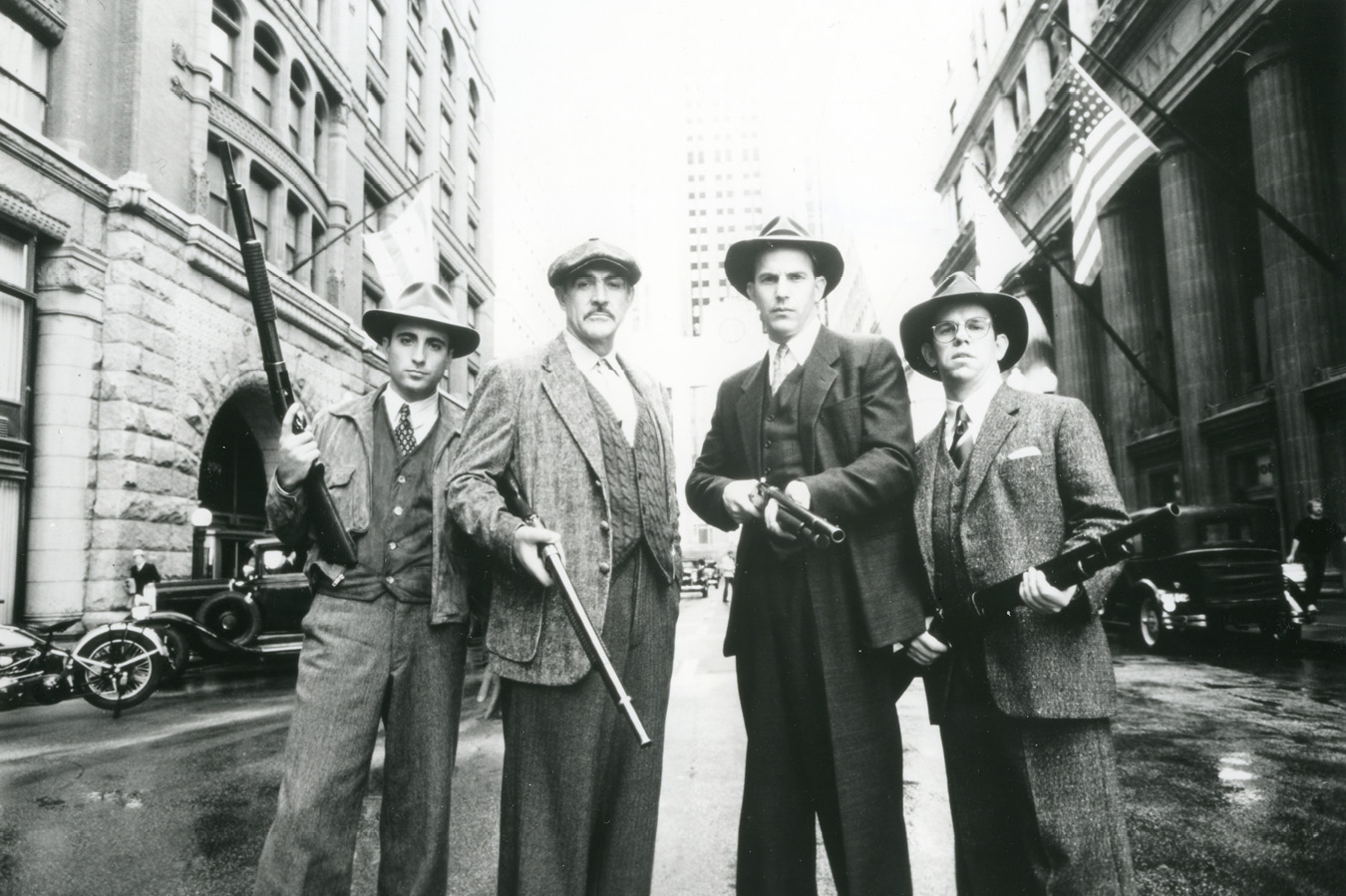

Soon thereafter, we see Eliot Ness of the Treasury Department being introduced to the local press and vowing to enforce Prohibition as the “law of the land.” Kevin Costner said that he saw Ness not as a “flashy guy,” but as a “stable guy” who is determined to catch Capone. Ness recruits three men for his task force: Jimmy Malone (Sean Connery), an Irish cop with many years of experience on the force; George Stone (Andy Garcia), an Italian American anxious to improve the image of Chicago Italians, which has been sullied by Capone and his Mafia mob; and Oscar Wallace (Charles Martin Smith), an accountant who repeatedly reminds Ness that he can nail Capone for tax evasion because Capone has not paid his taxes since 1926.

Malone surreptitiously meets with Ness in a church (Connery’s suggestion for the script) so that the Chicago cops on Capone’s payroll are unable to eavesdrop on their conversation. Malone’s advice to Ness: “He pulls a knife, you pull a gun. He sends one of yours to the hospital, you send one of his to the morgue. That’s the Chicago way, and that’s the way we’ll get Capone!” The “Chicago way” seems to be to fight fire with fire.

After Ness executes a successful brewery raid on a Capone warehouse, Capone has a dinner meeting with his top gang members. “De Palma’s visual panache is never more striking than in the banquet scene, when De Niro’s Capone caps a dinner speech with a few fatal swings of a baseball bat,” aimed at one of Capone’s henchmen, who did not short-circuit Ness’s raid on Capone’s brewery.18 Capone comments to those present that the guy was not a team player. By contrast, Ness’s three comrades are nothing if not team players.

Andy Garcia, Sean Connery, Kevin Costner, and Charles Martin Smith in Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987).

Later, Alderman John O’Shea (Del Close) attempts to bribe Ness with an envelope filled with money to lay off the Capone gang. Ness refuses the payoff by throwing the envelope in O’Shea’s face. O’Shea declares, “You fellows think you are untouchable, but everybody can be gotten to.” Shortly afterward, Frank Nitti (Billy Drago), Capone’s enforcer, threatens Ness’s family. Earlier, during a confrontation in the lobby of Capone’s hotel, Capone had shouted at Ness, “Fuck you and fuck your family!” So Ness sends his wife, his little girl, and his infant son away for safekeeping. Family is a key concept in the movie: aside from his wife and children, Ness has another family, his comrades in the Untouchables.

Ness gets wind of a cargo of whiskey being shipped from Canada to Chicago. He alerts the Canadian Mounties and heads with his team to the Canadian border. Ness and his men bide their time in a cabin near the border. Ness shoots one of Capone’s gang dead on the porch of the cabin in the opening exchange of gunfire. Inside the cabin, Malone endeavors to get another of Capone’s mobsters, who does not know that the first man is dead, to spill what he knows about Capone’s rackets, but the second mobster refuses. Malone goes out on the porch, grabs the corpse, props it up against a wall, and says he is going to shoot the guy if he doesn’t talk. Malone then puts a gun in the corpse’s mouth and pulls the trigger. Inside the cabin the other mobster decides to talk. Malone’s quick, brutal action demonstrates that he is aware that “law enforcement is beginning to resemble gang warfare.”19

In reprisal, Capone orders Nitti to murder two of Ness’s team. (In reality, Ness had ten men on his team, and one was killed by a Capone mobster; in the film, Eliot Ness has four men, and two of them are killed.) In the movie, Nitti shoots Wallace while disguised as a policeman (thus recalling the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre) in an elevator. Nitti also shoots Malone through a window in his apartment with a double-barreled shotgun. Ness finds the fatally wounded Malone just before he expires. An Irish Catholic, Malone bestows on Ness his medal of St. Jude, patron of lost causes. Ness will subsequently pass the medal on to George Stone, an Italian Catholic.

Capone, in due time, is put on trial for tax evasion; Ness learns that Capone’s bookkeeper, Walter Payne (Jack Kehoe), is taking the midnight train to Miami to avoid testifying about Capone’s finances. Ness takes Stone along with him to Union Station to intercept Payne so that he will have to appear in open court at the Capone trial. In the script, the railway station sequence, in which Ness and Stone track down Payne, involves a train wreck, but that proved to be too expensive. So De Palma dreamed up an alternate version of the Union Station sequence that is not in the shooting script. Part of it was suggested by Sergei Eisenstein’s classic Russian silent film Potemkin (1925).

In the sequence in Eisenstein’s Potemkin, which is called “The Odessa Steps,” Russian soldiers massacre peaceful demonstrators on the outdoor staircase near the city of Odessa. During the course of the slaughter, the mother of an infant is killed, and the baby carriage rolls down the steps, with no one to protect the baby.20 Similarly, in The Untouchables, Ness and Stone open fire on the gangsters who are guarding Walter Payne. When the shooting starts, a mother loses her hold on her baby carriage. “De Palma uses the station’s enormous staircase to recreate the drama of a baby carriage tumbling down the stairs while caught in a cross fire.” The director employs slow motion intermittently throughout the sequence to make the gun battle more riveting. “Ennio Morricone had the idea of using a child’s music box to provide the background music for the baby carriage slipping down the steps,” De Palma recalls.21 Neither the baby nor its mother stops a bullet in De Palma’s film.

After the shootout, Ness and Stone arrest Payne, who swears he will testify in court about the covert payoffs to Capone in his ledger, for which Capone never paid taxes. After Capone’s trial has concluded, Ness shouts at him in the courtroom, “Never stop fighting until the fight is over”—a motto he lives by. Ness follows Nitti to the roof of the courthouse to arrest him. Nitti sneers at Ness that Capone’s henchmen will see to it that the murder charges against him for killing Malone and Wallace will not stick. Ness goes berserk at the thought of Nitti walking away from the slayings of Ness’s comrades. He gets even with Nitti by hurling Nitti’s body “from the building, and it is pulverized as it crashes through the roof of a car.”22

In throwing Nitti off the roof, Ness is taking the law into his own hands. This implies how a law enforcement officer risks being tainted with the corruption of the gangsters he is pursuing. In actual fact, Ness did not kill Nitti, who shot himself in 1943, after being indicted for extortion and mail fraud.23 Asked why the scene of Nitti’s death is in the film, De Palma replied that he wished to show that the “gory deaths of Malone and Wallace motivate Ness to do things he never thought he could do. Also, Nitti being pushed off the roof allows the audience to savor a really bad guy being killed.”

Just before the final fadeout, a cub reporter buttonholes Ness on the street and inquires what he will do when Prohibition is repealed. He answers laconically, “I think I’ll have a drink.” The cognoscenti would know that Ness became an alcoholic after he moved to Cleveland later on, and an investigator for the Cleveland police force. He was involved in a hit-and-run accident while under the influence of liquor and forced to retire.24 But most people who see the film would not know of Ness’s inglorious end. Little wonder that he met Oscar Fraley, who would write his biography, in a bar.

As the viewer watches Eliot Ness stride down La Salle Street at film’s end, Ness is having his moment of fame. The Untouchables was also Brian De Palma’s moment of fame. The movie received accolades from critics and was a triumph at the box office. Although De Palma made some more good films, he never again made another film as good as The Untouchables.