Effective incident response forms the criteria used to judge cybersecurity programs. Effective protection and detection measures do not matter if the response to an event falls short. Within days of an announcement, news articles criticizing an entity’s response can negatively influence public opinion. Sizable data breaches elicit scrutiny that can last for years. Target became a prime example of this when it suffered a breach in 2014, and Equifax reinforced this fact in 2017. Criticism for not communicating news of the breach and possessing all the answers nagged both entities early in the response process. Equifax’s subsequent missteps beyond communication issues caused the incident response process to appear ineffective. These perceptions survive long after breach recovery has occurred.

A comprehensive plan that covers every fundamental aspect of incident response, practiced regularly, seems sufficient, until an incident actually occurs. The plan and the skills practiced can be forgotten. Individuals can panic, freeze, and fail to make decisions; others become cowboys, expecting to save the day. The hard truth remains: perceived cybersecurity program success lives and dies with effective detection, containment, eradication, and recovery from security incidents. Initial reports and public scrutiny seem to center on how long it takes entities to disclose incidents.

Information security blogger Brian Krebs broke the news of the Target breach,1 causing the retailer to lose its ability to control and manage messaging of the event. Equifax experienced the same issues. These included accusations made against executives, victims directed to vulnerable web sites, and speculation that the same attackers breached Equifax months earlier, casting a long shadow over Equifax’s response to the breach.2,3

Why Does This Happen?

Incident response is the face of an entity’s cybersecurity program. This places a strong emphasis on the need for an effective response program.

Common Themes Found in Ineffective Incident Response Plans

Cause | Details |

|---|---|

Lack of Planning | The incident response plan and playbooks are inadequate, missing key processes and actions. |

Lack of Preparation | Effective incident response requires muscle memory. Continuously referring to the response plan, trying to find the correct steps in playbooks, and not knowing what steps are necessary because specific scenarios were not anticipated lead to failure. |

Lack of Leadership | The program requires effective leadership on the team and from management. Individuals who panic and lose their cool in the heat of battle do little to forge an effective response. |

Lack of Management Support | Response teams cannot second-guess themselves during an incident. If taking systems offline is the necessary action then senior management criticizing such actions because it possibly affected the business does not demonstrate strong backing by management. |

Incident response programs require prioritization within the overall cybersecurity program and management must view incident response as an important business function. This means doing more than writing an incident response plan and conducting a tabletop exercise once a year. Operating as a program means that incident response undergoes continuous review and improvement on a regular basis. The plan must be fluid, and each event, incident, and breach responded to is an opportunity for analysis of what went well and what opportunities for improvement exist. Frequent testing of the program and its processes yield beneficial feedback. A road map outlining the trajectory of the incident response program, from initial development to mature program backed by effective processes, drives annual projects and actions.

While laying the groundwork for the program the members of the team must prepare themselves. There is no substitute for practice. Reviewing your risk analysis, documenting other breaches, and referring to resources such as Mandiant’s Attack Life Cycle make it easy to generate practice scenarios. I am not talking about high-tech practice. The team picks a scenario and then walks through the process of analysis, triage, and response. At the end of each walkthrough, the team identifies what works and what does not and adds missing pieces in the response playbooks.

Components of an incident response program developed those leading the response

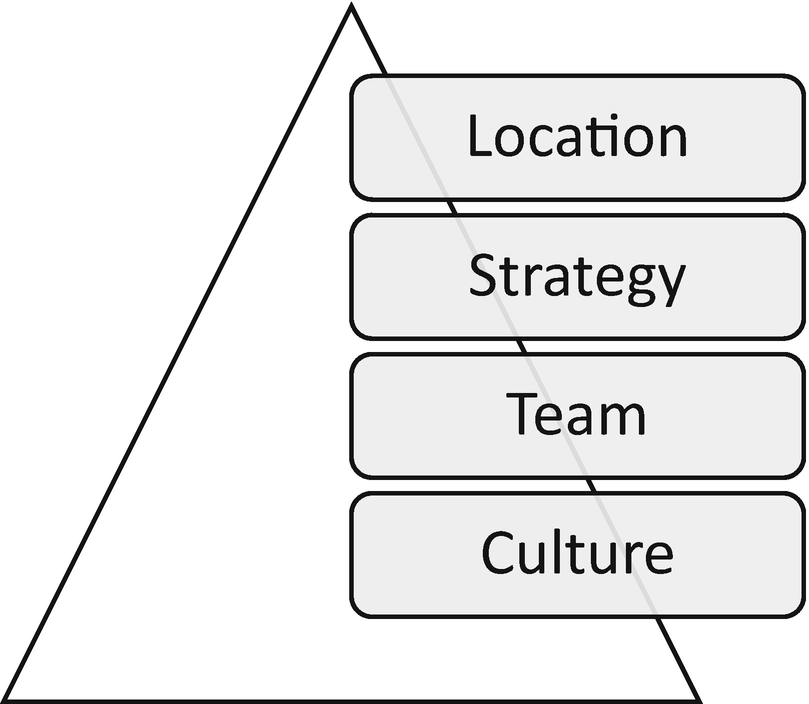

Leaders start by defining the culture of the organization they direct. This applies to the incident response program too. In Chapter 5, an in-depth review of culture and its importance to success illustrates how culturally defined behaviors are meant to lead the program toward success. Leaders begin by getting the right people on the team.4 Choosing the incident response team consists of more than selecting the smartest or most technically gifted individuals. Team members aligned with the goals, objectives, and cultural expectations prove more valuable than technically gifted individuals, if the latter do not buy into the program’s goals and objectives.5 Once culture and team requirements are established, the strategy to meet the program’s goal—to detect, contain, eradicate, recover, and assess lessons learned quickly, while minimizing damage to the entity—requires individuals with specific talents. If those talents do not exist internally, strategic partnerships must be established with external parties. This gap is not identifiable until the team is created. This strategic element is not defined until the team is identified. In Good to Great, Collins defines location as the need for businesses to know where they want to compete. This also applies to incident response. Will key incident response processes remain on-premise or off-premise? Will they be executed by a third party? Small and medium-size organizations often lack the resources to execute all elements of an incident response internally. Large organizations also rely heavily on outside professionals for vital incident response processes.

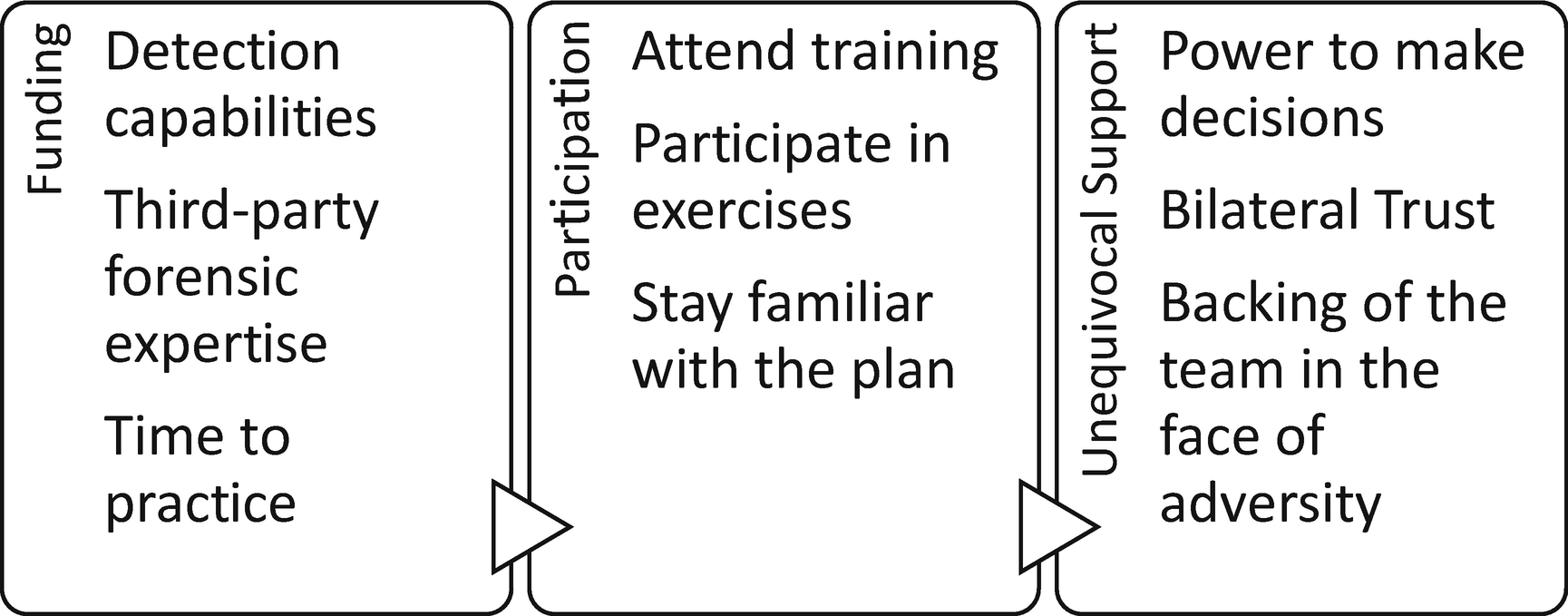

The incident response program’s requirements, from left to right, are dependent on the factors in the preceding box

Technical first responders must rehearse responses to varying incident types and make improvements to playbooks.

Leaders must rehearse scenarios and evaluate decision making.

The executive team must rehearse how it takes in information, evaluates the scenario, and makes decisions.

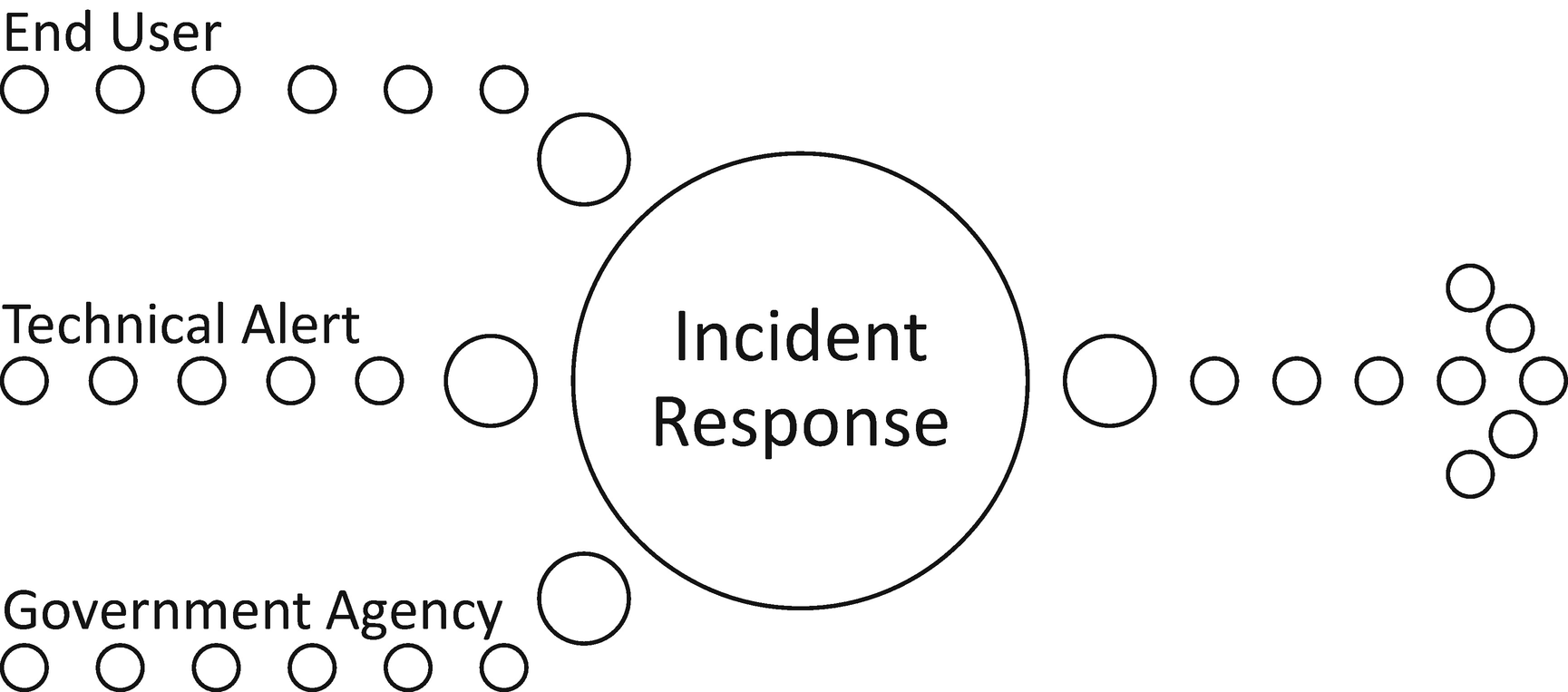

Three common ways events and incidents may be detected

End-user reporting, monitoring tools, and government agencies are common sources of alerts. It is not unusual for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to uncover evidence of a potential breach when investigating other intrusions. No matter the source of the alert, team members must be able to triage the situation and know automatically the next step in the process. These actions must be intentional, purposeful, and skillful.6 There is no room for ad hoc behavior that does not follow the plan. This applies to executives as well. The executive team must attend all training, participate in training exercises, and keep abreast of the plan.

Strategy vs. Tactics

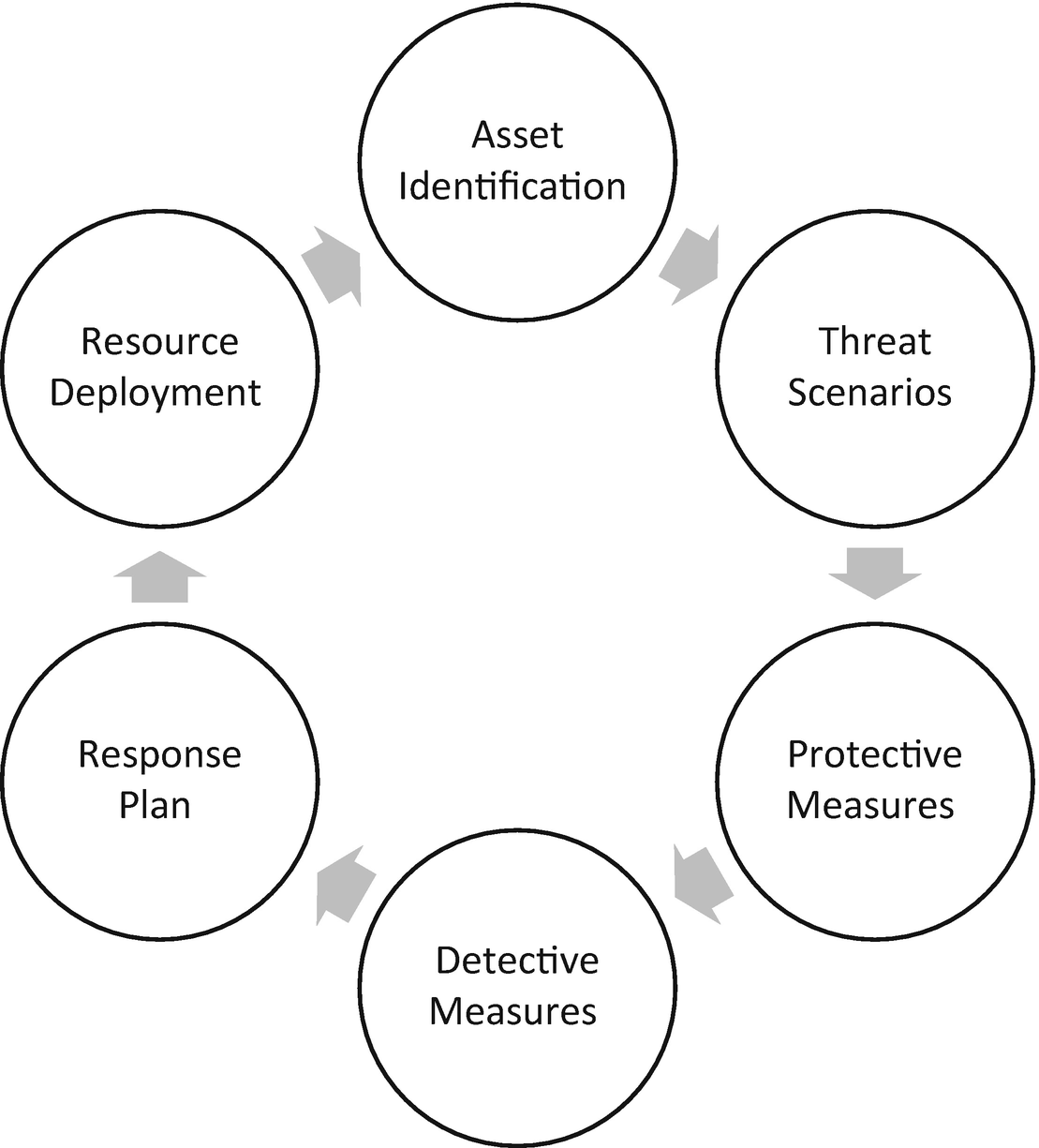

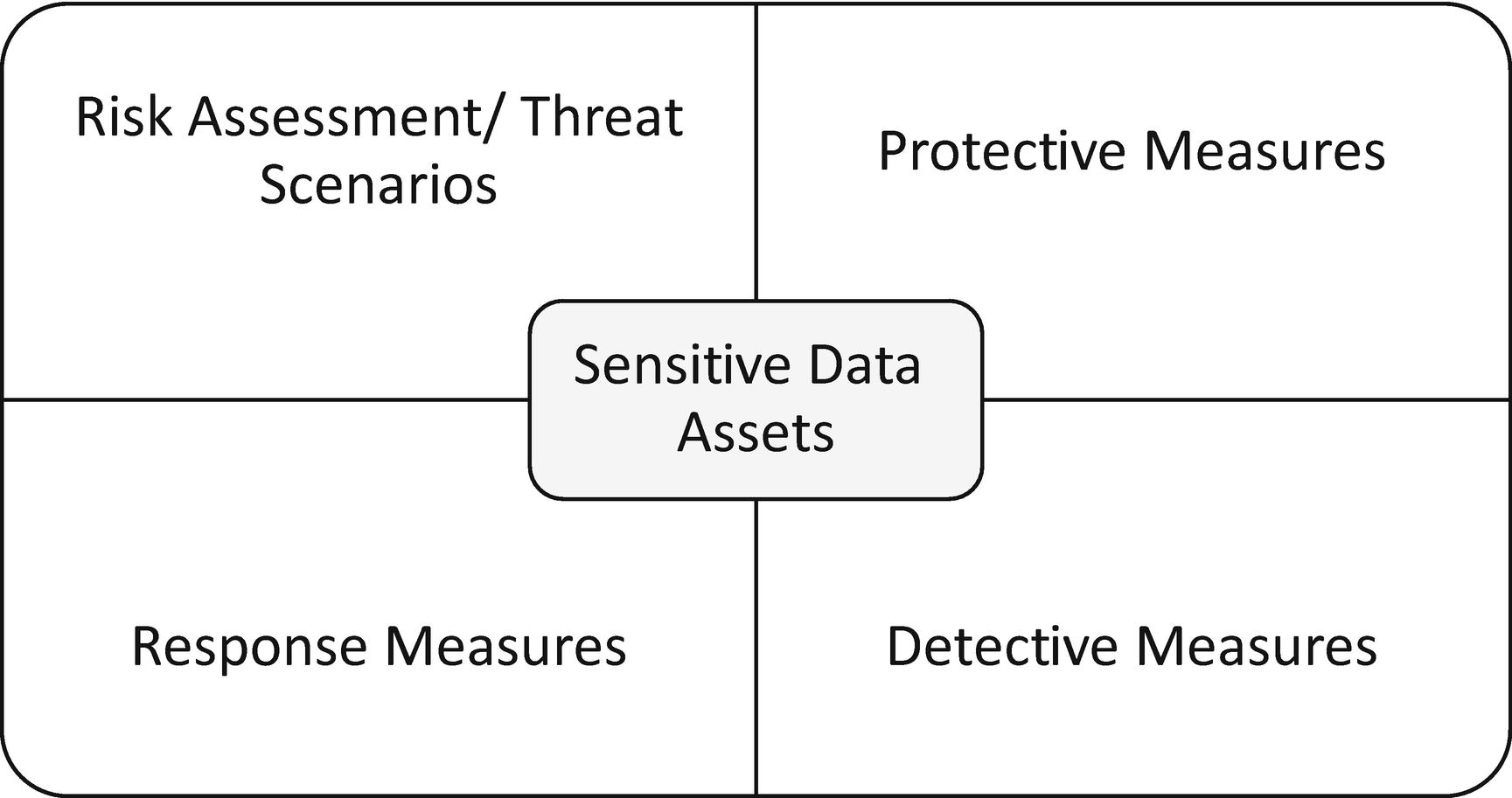

Cyclical approach to building a strategic response plan

Continuous analysis and review take place through practice exercises and reviewing actual events. New threats or intelligence about an attacker’s processes, tactics, and techniques (PPTs) and indicators of compromise (IOCs) push the team to analyze this data in terms of affected assets. The team must understand if the protective, detective , and response capabilities are adequate. If not, alternative or compensating processes must fill the void.

The incident response program deploys sensitive assets, drawing the program’s attention and resources toward what matters most to the organization

Tactics, which come in the form of playbooks , runbooks, or checklists, outline the specific actions expected for a type of event or incident. Playbooks for ransomware, malware, unauthorized access, data theft, and several other scenarios designate specific actions required to meet program objectives.

Changing the Culture

To achieve the goal of building an effective incident response program, changes in how senior management, information technology, and cybersecurity personnel think about incident response may be necessary. Annual testing and remediation as an approach to response preparation is considered sufficient. This approach is used by most entities today. Auditors and regulators also accept this approach when assessing entities. Cybersecurity auditors consider this sufficient and rarely challenge auditees on this notion.

Senior management must embrace incident response as a program vital to organization objectives and support it with the necessary resources and commitment. Too often, the C-Suite does not consider cyber/information security as anything more than a cost function or necessary evil. Despite increased accountability and scrutiny in the face of breaches and breach response, little seems to change.

To combat these challenges, effective organizational change management is necessary.

Note

If responding to an incident drives public perception of the entity and its ability to act responsibly, shouldn’t executives invest the time necessary to make the incident response program successful?

Several models and approaches exist to aid the drive of organizational change and achieve buy-in from the internal stakeholders with the influence necessary to make the program successful. These models are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3.

Summary

Leadership

Preparation

Execution

Leadership is the number-one need and driver of successful incident response. Leaders must ensure that the right people are part of the response team, create a culture focused on the necessary behaviors leading to success, and keep calm in the face of a storm. Leaders cannot lose control of emotions, allow team members to act outside of their role on the team and deviate from the incident response plan.

There must be consistent practice, ranging from full-blown tabletop exercises to smaller scenarios using specific playbooks. The goal is to develop muscle memory, helping team members to get comfortable with their roles and instilling confidence in their ability to respond appropriately.

Migration from traditional approaches to incident response, which centers on annual tabletop exercises, requires change in how the organization thinks about incident response and preparation. Effectively changing behaviors toward incident response across all members of the entity is the most important success factor for incident response.