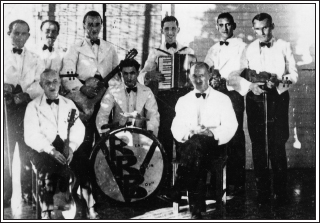

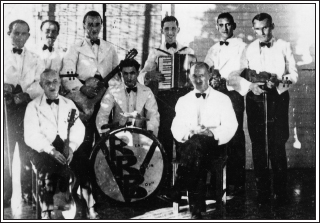

The Beau Bassin Boys, ca. 1941–45. Erich Weininger is the violinist on the far left. (Courtesy of the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, Israel.)

Butcher and amateur violinist Erich Weininger was twenty-five years old and living in Vienna on March 11, 1938, when Austrian chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg delivered an earth-shattering address over the radio. In a trembling voice, Schuschnigg announced that he would be resigning and handing over power to the Nazis. Schuschnigg’s efforts to suppress the rise of Austrian Nazism had failed, as had his attempts to establish peace with Hitler. With no foreign powers willing to come to Austria’s aid, Schuschnigg had no choice but to peacefully surrender to the Nazis in the hopes of avoiding a bloody German invasion. Schuschnigg bade farewell to his country with the words “God save Austria!”22

The radio followed Schuschnigg’s address with the theme from the slow movement of Haydn’s String Quartet in C Major, op. 76, no. 3. The melody is one that Haydn wrote in 1797 in honor of Holy Roman Emperor Francis II. In 1938, the tune served as the national anthems of both Austria and Germany. Austrians who were hoping to avoid being annexed by Nazi Germany would have instantly noted the irony of broadcasting a song they knew to begin with the words “Blessed be, without end, wonderful homeland.” Pro-German Nazis no doubt appreciated the manifestation of the song they knew as “Germany, Germany, above all.”

The German army marched into Austria later that night, but by that time the Nazi takeover was already complete. Immediately after the closing bars of Haydn’s anthem, Austrian Nazis took to the streets, shouting and waiving swastika flags. “One people, one Reich, one Führer,” they chanted. “Die, Jews!”23

The Nazi marauders commandeered Jewish-owned vehicles and businesses. They vandalized Jewish homes and shops. They grabbed Jews off the streets, pushed them onto their hands and knees on the sidewalks, and forced them to scrub away the slogans for Austrian independence that had been painted there just days earlier. “At last, the Jews are working,” the mob taunted. “We thank our Führer, who has created work for the Jews!”24

The anti-Semitic regulations that the Nazis had systematically implemented in Germany over the previous five years were extended into Austria virtually overnight. Jews could neither attend schools and universities nor practice any professions. They were forced to relinquish their businesses and property for compensation that was nominal at best. They were forbidden from eating at public restaurants, visiting public baths, entering public parks, and going to public theaters, and were regularly subjected to ridicule and intimidation. Over the next three months, seventy thousand Austrian Jews were arrested, principally in Vienna. Most were harassed and tortured for a few hours or days before being released.

The Nazis quickly began turning their attention from humiliating and terrorizing the Jews to expelling them from Austria. On April 1, all of the prominent Jewish leaders in Vienna were sent to the Dachau concentration camp. In May and June, an additional two thousand Jewish intellectuals who had been specifically targeted by the Nazis were arrested, beaten, and placed on three trains to Dachau. This included Erich Weininger, who arrived at the concentration camp on June 3, 1938.

Dachau

One of the first Nazi concentration camps, Dachau was established in March 1933, just weeks after Hitler came to power in Germany. The camp was constructed on the site of an abandoned World War I munitions factory ten miles northwest of Munich. Initially built to accommodate five thousand German inmates, its original detainees were political prisoners such as communists and social democrats. The ranks soon grew to incorporate other factions that the Nazis deemed undesirable, including homosexuals, Roma (Gypsies), and Jehovah’s Witnesses. When Erich arrived in Dachau, he was among the first non-Germans to be detained in a concentration camp. He was also among the first to be imprisoned simply for being Jewish.

Erich was arrested by the Austrian police at the end of May along with several hundred other Jews, including the famous psychologist Bruno Bettelheim and the composer and conductor Herbert Zipper. They were taken to a detention center in a converted school on Karajan Street—named after the personal physician of Emperor Franz Joseph I who was the father of the already famous conductor Herbert von Karajan. They expected to be released within a couple of hours or days, as many of them had been after previous arrests. But this time, they would not be allowed to return home.

After a few days, the Jews were loaded into police vans and taken to Vienna’s western train station. When the van doors flew open, they were greeted by SS guards who ordered them to run. The Nazis savagely struck the prisoners with fists, clubs, whips, rifle butts, and bayonets. They corralled them through the station and toward a train, dragging anyone who stumbled by the hair. Those who resisted were shot. Those who survived sustained serious injuries. Bettelheim was savagely beaten in the head and stabbed with a bayonet. Zipper suffered severe facial trauma and two broken ribs.

It took thirteen hours for the train to travel the three hundred miles to Munich. The trip was continually interrupted for sessions of torturous exercise and brutal beatings. The passengers were ordered to sit up straight with their hands on their laps. They were forced to stare straight into blinding lights that hung from the ceiling. Several faltered during the night and were beaten or shot to death. When the train arrived in Munich the next morning, the Jews were packed into cattle cars—150 in each car—for the final leg of the train ride to Dachau.

Upon their arrival in the concentration camp, the prisoners were stripped of their remaining possessions, shaved, and dressed in ill-fitting striped uniforms. Prisoner life was governed by very strict rules. Breaking them would result in severe punishment. “Everything in Dachau is prohibited,” the camp commandant announced. “Even life itself.”25 Although Dachau was technically an internment center and not a death camp, its prisoners were subjected to starvation, beatings, torture, and grueling forced labor. During the Holocaust, at least 31,591 of its 206,206 detainees died from malnutrition, exhaustion, disease, suicide, and murder at the hands of the SS guards.

Although the prisoners were closely watched most of the time, the guards often left them unsupervised on Sundays. Some took advantage of their free time to socialize with other captives or read newspapers. Others wrote to their families. They were allowed to send two short letters each month. Herbert Zipper did something quite extraordinary: he formed a clandestine orchestra.

Shortly after arriving in Dachau, Zipper had met several excellent musicians, including a number of outstanding string players. He had also heard that there were one or two violins and just as many guitars that had somehow been brought into the camp. These discoveries inspired Zipper to form a makeshift ensemble. Given the low number of instruments available in Dachau, it is very likely that Zipper’s orchestra included Erich, who had managed to bring his violin with him from Vienna. To complete the ensemble, Zipper convinced two instrument makers in the camp wood shop to secretly build instruments out of stolen wood. He even persuaded an SS guard to smuggle in some violin strings.

Zipper’s fourteen-piece orchestra performed in a latrine building that was still under construction. Their repertoire consisted of well-known classical works as well as music that Zipper composed in his head each week during forced labor. He wrote out the pieces late at night, making sure to accommodate the odd instrumentation and the varied skill levels of the musicians, when he was supposed to be cleaning toilets. Zipper notated the music on strips of paper that fellow prisoners would tear from the margins of Nazi newspapers and painstakingly paste together.

There was only room in the unfinished latrine building for twenty to thirty people at a time, so the orchestra played in shifts of fifteen minutes to allow as many audience members as possible to rotate through the performances. The prisoners filed in quietly and remained in conspiratorial and awed silence throughout the brief concerts. In a tightly controlled concentration camp like Dachau, where such pursuits were strictly forbidden, the musicians and the audience members risked torture or even death for participating in these unsanctioned concerts.

In addition to providing a source of emotional comfort for the detainees, the music served as an inspirational reminder of the humanity that Dachau had taken from them. When they listened to the music, they were no longer weak, demoralized, and humiliated. They were dignified and strong, united in their spiritual resistance to Nazi persecution. If only for fifteen minutes a week, they were surrounded not by the ugliness of the concentration camp but by the beauty of music.

In 1938, the Nazis were still more concerned with expelling Jews than with killing them. Their solution to the “Jewish Question” continued to be coercing Jews into emigrating. They were even willing to release concentration camp prisoners who agreed to leave the country. Most of Dachau’s detainees, especially those who promised to surrender their property and move away, were released after several months. More than 1,200 others, including Weininger, Bettelheim, and Zipper, were packed into four cattle cars and transferred to the Buchenwald concentration camp on September 23, 1938, to make room in Dachau for an influx of Jews from the German annexation of the Sudetenland. A convoy of 1,100 Jews followed one day later.

Buchenwald

Established five miles north of Weimar in 1937, Buchenwald was one of the largest concentration camps on German soil. Like Dachau, Buchenwald was designed as an internment facility and not specifically a death camp, as Auschwitz would later become. But Buchenwald’s harsh conditions—far worse than those at Dachau—nevertheless claimed the lives of 43,045 of its 238,980 prisoners during the Holocaust. Many died of starvation, while others were literally worked to death under the Nazis’ brutal “Extermination Through Labor” policy. Still others succumbed to disease or were simply murdered by the SS guards.

Erich brought his violin to Buchenwald, but there was no possibility of participating in performances—even clandestine ones. Immediately upon arriving, the prisoners were told that gatherings of any kind were strictly forbidden. If any of them witnessed anyone breaking those rules, they were to report it immediately or risk being punished themselves. Such punishment typically involved being stretched out on a whipping post and beaten on the back twenty-five times with a whip or a club.

When Erich arrived in Buchenwald, there were about ten thousand prisoners, living in unbearable conditions. Unlike Dachau, which had been systematically clean and orderly, Buchenwald was filthy. There was no running water until January 1939, forcing the detainees to go for months without bathing or brushing their teeth. The appalling hygiene was exacerbated by the nonstop rain and the unpaved roads, which covered everything and everyone with slimy mud. The toilets were four large ditches, twenty-five feet long, twelve feet wide, and twelve feet deep. Since there was nothing to hold on to while they were relieving themselves, exhausted prisoners often fell or were thrown by SS guards into the foul trenches, where many of them died.

The situation in Buchenwald grew even worse on November 10, 1938, when the prisoner population was instantly doubled with the addition of ten thousand Jews who had been arrested on Kristallnacht. Five additional barracks had been built in the preceding weeks, but they were hardly enough. Each night, eight hundred detainees were locked in barracks built for four hundred. Many died of suffocation overnight. Others died of starvation from only receiving half of the already paltry food rations. Still others succumbed to typhus when an epidemic ran rampant through the cramped and unsanitary camp.

Throughout their incarceration in Buchenwald, the prisoners were subjected to various forms of torture. This included “sport” sessions in which the SS guards would force a few of them to exercise until they died of exhaustion. Sometimes the torture was inflicted on the entire camp at the same time, as when the guards would make the detainees stand at attention in the freezing cold. On December 14 and 15, 1938, the captives stood from 5 p.m. to noon the next day as punishment for two prisoners who had escaped. Several dozen of the flimsily clad detainees died of exposure while countless others, including Bettelheim, suffered frostbite as the temperature dropped to 5 degrees Fahrenheit overnight.

At this time, the Nazis were still promoting mass emigration as a comprehensive method of ridding Germany and Austria of their Jewish populations. In August 1938, Adolf Eichmann established the Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Vienna to expedite the expulsion process. Jews who were able to pay a hefty Reich Flight Tax and other fees were allowed to emigrate, but only after surrendering all of their wealth and possessions to the Nazis, and only if they agreed to leave the country as soon as possible. Even those in the concentration camps were released if third parties paid the fees and obtained the requisite paperwork on their behalves. The 9,370 Jews who were released from Buchenwald in the winter of 1938–39 included Zipper, who returned to Vienna on February 20, 1939, after his family secured the documents necessary to immigrate to Uruguay. Bettelheim was released on April 14, after obtaining a passport, visa, and ticket to the United States.

Zipper and Bettelheim were fortunate to secure their departures in early 1939. By that August, the Nazis were no longer issuing exit permits to male Jews between the ages of eighteen and forty-five. Within the next two years, they would put a stop to all Jewish emigration. The very last group of Viennese Jews who were allowed to leave Austria departed for Portugal in October 1941. By then, the Nazis had concluded that the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” was not the expulsion but the extermination of the millions of Jews who remained in Nazi-occupied Europe. One year later, the Nazis would order all Jewish prisoners remaining in Buchenwald to be transferred to Auschwitz.

The Jews who were able to emigrate prior to 1940 were assisted by numerous international relief organizations. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and England’s Council for German Jewry each provided funds for one hundred thousand or more Jews to leave Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia. The German Emergency Committee, established in London by Quakers, rescued another six thousand Jews.

Among those whom the German Emergency Committee freed from the concentration camps was Erich, whose sister-in-law was a Quaker who had emigrated from Vienna to London one year earlier. First, she was able to pressure the Nazis into releasing her husband—Erich’s brother Otto—and then she got them to free Erich. Thanks to the Quakers, Erich was released from Buchenwald and was allowed to return home to Vienna. From there he was able to leave Nazi-occupied Europe—becoming one of the last Jews to escape the Holocaust.

Erich’s father Karl, conversely, decided not to leave. He was reluctant to undertake the arduous process of emigrating, especially since he was among the many German and Austrian Jews who were convinced that the Nazis would not be in power for very long. His decision would prove to be fatal. One day, Karl wore an overcoat on top of the jacket onto which he had sewn his Star of David. In the cold Vienna winter, he had briefly forgotten that Jews were required to visibly display the yellow badge at all times. A close family friend who had often dined at the Weiningers’ home informed on the elderly Weininger to the Nazis. Karl was arrested, taken to a police station, and pistol-whipped to death.

Bratislava

By the end of 1939, half of the 525,000 Jews who had been living in Germany before the Nazis took over had left the country. Half of Austria’s 200,000 Jews had also fled. Some went to North America, South America, Eastern Europe, or Asia. Others, like the musicians who formed the Palestine Orchestra, had immigrated to the Holy Land.

By that time, however, there were fewer and fewer places left to go. The countries that had been accepting Jews since 1933 had become overwhelmed with refugees. Some began instituting strict quotas. Others closed their borders altogether. Even Palestine ceased to be an option for most Jews after Great Britain responded to ongoing Arab unrest by issuing the White Paper of 1939, which greatly reduced the numbers of Jews who could immigrate there. Such limits placed severe restrictions on Jewish immigration just at the time when European Jews needed asylum the most.

There may be no story that encapsulates the frustrating impracticalities of the emigration process better than the saga of the MS St. Louis. The ocean liner left Hamburg on May 13, 1939, with 937 immigrants bound for Cuba, where most planned to stay only until their American visas came through. The majority of the passengers were German Jews, including Günther Goldschmidt’s father Alex and uncle Helmut. Many of them had been imprisoned alongside Erich in Dachau and Buchenwald. When the St. Louis arrived in Havana, its passengers learned that the Cuban landing permits for which they had paid inflated fees had been revoked. Cuba was closing its doors to immigrants. By this time, one of the original passengers had died of congestive heart failure, leaving 936. Of those, 28 passengers who had paid five-hundred-dollar bonds were allowed to disembark, while the remaining 908 passengers were denied entry.

In the hopes of protecting his passengers, the German captain rerouted the St. Louis to Florida, only to be turned away by the U.S. Coast Guard. The United States had already filled its quota of German immigrants for the year, and refused to accept any more. The captain reluctantly set sail back to Europe, docking the St. Louis in Belgium instead of returning to Nazi Germany. Great Britain welcomed 287 refugees. One Hungarian businessman returned home. The remaining 620 passengers found refuge in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Being outside of Nazi Germany brought a reprieve from danger, but only briefly. As Germany occupied more and more of Europe, the 620 refugees on the continent found themselves in danger once more. By the end of the Holocaust, 254 of them would be dead, including Alex and Helmut Goldschmidt.

Erich and the other Jews in Germany and Austria were well aware of the difficulties with emigrating. With few options at their disposal, thousands of them decided to immigrate to Palestine illegally. Many of them had been fully assimilated into European culture and would have never otherwise considered moving to Palestine. Even some of the staunchest Zionists were reluctant to risk breaking the law in such tenuous times, especially if doing so would weaken the relationship between Jews and Great Britain. But they could not find any alternatives. There was simply nowhere else to go.

A number of Jews sought assistance from the Zionist organization Hechalutz (Pioneer), which prepared young Jews for immigration to Palestine. Erich was one of many hopeful colonists who lived on training farms sponsored by Hechalutz. These camps offered instruction in agriculture and other trades to give future settlers the skills they would need to successfully integrate themselves into the Jewish community of Palestine.

When the Hechalutz office in Vienna was unable to secure passage to Palestine, Erich and many others turned to Jewish financier Berthold Storfer, who had been named director of the Committee for the Transportation of Jews Overseas by Adolf Eichmann himself. For the Nazis, facilitating illegal immigration killed two birds with one stone: it would rid Europe of more Jews while also irritating the British government, which was struggling to maintain peace between the Arabs and the Jews who were already in Palestine. Viennese Jews would begin lining up at Storfer’s office before midnight, hoping that the next day would bring the paperwork that would enable them to emigrate. Since some certificates expired quickly, the Jews would have to return every two months until their transports could be arranged.

While they waited for Storfer to orchestrate their emigration, the Jews continued to be terrorized. Nazi hooligans would grab them off the streets—sometimes while they stood in line in front of Storfer’s office—and force them to wash their cars, polish their boots, or scrub the pavement to the delight of jeering onlookers. The Jews could not even feel safe in their own homes. The Gestapo could knock on the door at any minute. “They came at night, hauled us out of bed, beat me, the wife, and the children, broke up the furniture, and threw the pieces out the window,” recalled one victim.26 Others were taken into “protective custody,” which meant torture and sometimes death.

After several months of anxious anticipation, the first group of Austrian and German Jews aided by Storfer’s committee left Vienna on December 15, 1939. The plan was to take the train to Bratislava, the capital of the newly formed Slovak Republic. After staying in Bratislava for a few days, the Jews would be transported down the Danube by the Nazi-owned Danube Steamboat Company, naturally in exchange for exorbitant fares. Once they reached the Black Sea, the Jews would board the Greek steamship Astrea, which Storfer had chartered to sail to Palestine.

Nothing went according to plan.

The Jews arrived in Bratislava at midnight. They were met by members of the Hlinka Guard, which served as the internal security force for the pro-Nazi Slovak government. They were taken to the Slobodárni, a cheap hotel near the train station that was already filled with Czech Jews who had arrived a few days earlier. Some of the new arrivals staked their claim to floor space in overcrowded hallways and lounges as the remainder of the Jews from Vienna began to arrive. Others were taken just outside of town to the Patrónka, a hodgepodge of derelict huts and barracks that had once been a bullet factory and was now the home to 190 Czechs.

The German and Austrian Jews in the Slobodárni and Patrónka quickly learned from their Czech counterparts that the Danube had frozen over, leaving no possibility of sailing to the Black Sea. Any hopes of finding another method to continue their trip were dashed several days later, when they learned that the Astrea had sunk during a storm. For at least the foreseeable future, the Jews would have no choice but to remain in Bratislava in conditions that could hardly be considered ideal. Their Slovak transit visas were only valid for limited periods of time, forcing them to continually renew their paperwork by bribing corrupt officials. Until they could find a way to leave, the sojourners would be confined to the Slobodárni and the Patrónka by the Hlinka Guard. To add insult to injury, the Jews were forced to pay for the substandard lodgings in which they were being detained.

The Slobodárni was an ugly five-story building that the city had built as a boardinghouse for single men. It was never designed to hold hundreds of refugees. In one overcrowded lounge, 120 men shared sixty soiled and worn-out mattresses. There were only two toilets and one sink, and no place to wash clothes or dishes. The several hundred occupants of the Slobodárni were taken outside twice a day, when they were allowed to slowly amble around a small courtyard for fifteen minutes.

Life in the Patrónka was even worse. The 190 Czechs, 200 Austrians, and 400 Germans detained there slept on wooden bunks covered in straw. The roof of the abandoned factory often leaked, soaking the straw beds. The windows were either broken or missing altogether, giving the tiny iron stoves in each hall no chance to protect the building from the freezing winter. Sanitation was also a problem. There was only one water tap, and the toilets were outdoors.

By the spring, the conditions had improved somewhat. The Hlinka Guard relaxed their oversight, and the Jews were allowed to venture into Bratislava, where they went shopping, read newspapers, made friends, and even found work. Some took walks in the nearby hills and woods, picking flowers. Others stayed inside, playing cards and chess or engaging in classes, discussion groups, and debates. One refugee later recalled a number of recitals in which Dr. Hans Neumann and another gentleman played the piano and violin. It is possible that the unnamed violinist was Erich.

Over the summer, the situation worsened yet again. As the Slovak Republic was increasingly consumed by Nazism, the Hlinka Guard reinstituted stricter security measures. The Slovak authorities grew frustrated that the Jews who had been issued temporary transit visas remained in their borders, and threatened to send them back. On June 17, 1940—the day that France announced that it would surrender—the Jews were ordered to pack their bags for deportation to Germany, where they would surely have been sent to concentration camps. The expulsion was averted with more bribes, but the need to leave Bratislava was becoming increasingly urgent.

Down the Danube and to the Mediterranean Sea

Back in Vienna, Storfer had been working hard to get the Jews out of Europe. He had secured a large amount of funds from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee to pay for the trip. He had also contracted the same company that had owned the Astrea to charter larger ships for the growing numbers of Jewish refugees gathering not only in Bratislava, but also in Berlin, Vienna, Danzig, Prague, and Brno. The Greek shipping company had started looking for new vessels as well as for a neutral country that would allow them to sail under its maritime flag. But delays in the funding and difficulties with securing passage to the Black Sea threatened to cancel the voyage yet again.

It was not until the afternoon of August 28, 1940, that the Jews finally began boarding the ships that would take them to the Black Sea. The Nazi vessels were already traveling down the Danube to pick up ethnic Germans from Russian-occupied Bessarabia and bring them back to the fatherland, so why not make some money off Jews along the way? A group of around two hundred refugees from the Patrónka joined five hundred from Danzig aboard the Helios, a pleasure ship that was designed to hold three hundred passengers. The Helios was later packed even further with the addition of three hundred Jews from the Slobodárni. Its sister ship the Uranus, which was also built for three hundred, was just as overcrowded, with four hundred refugees from Berlin and six hundred from the Slobodárni and the Patrónka. The Helios and the Uranus were joined a week later by two tour boats from Vienna, both built for only 100–150 passengers: the Melk, carrying 220 Jews from Brno and six hundred from Prague, and the Schönbrunn, carrying eight hundred Viennese refugees.

On the morning of September 4, the four Danube Steamboat Company boats left Bratislava, flying swastika flags and overloaded with more than 3,600 Jews. As the convoy departed, the Jews joined together to sing “Hatikvah.”

On their slow and cramped voyage down the Danube, the Jews were constantly reminded of how precarious their situation was. On September 6, they passed several hundred Jewish refugees from Danzig and Austria who were stranded on the banks of the Danube in Yugoslavia. Unable to secure further passage to the Black Sea, the Jews were later imprisoned and ultimately massacred after the Nazis invaded Yugoslavia. On the very next day, the Helios, Melk, Schönbrunn, and Uranus encountered the Pentcho, a paddle-wheel steamship that had left Bratislava four months earlier with six hundred Jews. The Pentcho had been detained for seven weeks in Yugoslavia after being deemed unseaworthy, and was now quarantined in neutral waters between Romania and Bulgaria for lacking proper paperwork. After several other delays, the Pentcho would make it to the Black Sea before wrecking in the Greek islands. Its haggard and emaciated passengers would be interned in Italy, but would immigrate to Palestine after being liberated by the Allies. The Helios, Melk, Schönbrunn, and Uranus were also delayed for three days in Bulgaria. They were released only so the Nazi ships could continue on their official missions to Bessarabia.

On September 12, the transport reached the Romanian port of Tulcea, where the Jews discovered three decrepit tramp steamers undergoing renovations. On the next morning, the refugees were surprised to find that the ramshackle freighters would be their transport to Palestine. The listing ships now bore Panamanian flags and the newly painted names Atlantic, Pacific, and Milos. “It was like naming a Pekinese ‘Nero’ or a Chihuahua ‘Caesar,’” one refugee later explained. “Except that these ships had never been thoroughbreds.”27

The 820 passengers from the Melk boarded the Milos and the one thousand Jews from the Uranus boarded the Pacific on September 14. The largest and oldest of the ships, the Atlantic, had been retrofitted to accommodate 1,200 passengers, but ended up quartering all 1,800 refugees from the Helios and Schönbrunn. It was on this cramped behemoth that Erich would continue his odyssey.

Erich and the other passengers were shocked to find that the Atlantic was even more crowded than the Helios and Schönbrunn had been. There were five toilets inside the ship to serve 1,800 refugees, but they would not even flush unless one brought a bucket of seawater. Most of the passengers ended up using the six makeshift lavatories on the deck, which had been so hastily constructed that they hung over the side of the ship. Since the Panamanian flag was painted on the roof of those lavatories, making a visit there became known as taking “a trip to Panama.”28

The tiny cabins and cramped bunks that had been constructed in the Atlantic’s holds were packed far beyond capacity, forcing many passengers to carve out whatever space they could in the hallways, decks, stairs, and the insufficient lifeboats. Even with these measures, the Jews had to take turns standing to ensure that others had enough space to sleep. They had to improvise makeshift kitchens in various corners of the ship. The quarrels that naturally ensued in such cramped quarters were policed by the Haganah (Defense), a band of refugees from Prague who took their name from the paramilitary organization that protected the Jews in Palestine.

After three weeks of frustrating bureaucratic delays, which were eventually resolved through more bribes, the Atlantic raised anchor at 10:45 a.m. on October 7 and started to follow the Pacific toward the Black Sea. The beginning of the journey was hardly auspicious. Lacking a radio and navigation instruments, the Atlantic traveled about two hundred yards before running aground on the muddy shore. The captain ordered the passengers to the back of the boat in an attempt to shift its weight from the front. After an hour of grinding its engines, the Atlantic freed itself of the mud, only to break down. The crew restarted the engines before once again running the Atlantic aground, damaging the rudder in the process. The Atlantic was slowly towed to the Black Sea port of Sulina for repairs, a process that delayed its departure for two days. The Pacific and the Milos sailed ahead.

The Atlantic finally got under way on October 9. As with everything else on the journey, the trip to Palestine took much longer than anyone could ever have anticipated. Rightfully worried that the Atlantic could be attacked by the German or Italian navy during its voyage through the Mediterranean Sea, the Greek captain would moor the Atlantic in various island coves during the day and sail only at night. When they were at sea, the captain would run the engines at full throttle to waste coal. The more often he could stop to refuel, the more often he could increase his profit margin by overcharging the desperate refugees.

The Atlantic anchored in Crete to refuel on October 16. Then another crisis presented itself: the captain would not continue the voyage.

From the beginning of the trip, the Jews had experienced problems with the captain and his crew. In addition to the initial troubles with running aground, the captain had continually extorted money from the refugees for the food, water, and coal for which they had already paid exorbitantly before their departure. Throughout the trip, the captain had acted erratically and had repeatedly tried to abandon ship. After the Greco-Italian War broke out on October 28, the Greek captain simply refused to sail into Italian waters.

The Jewish refugees would not allow the captain to delay them any further. They took command of the helm and the engine room and set sail on November 8, having wasted three weeks in Crete. They quickly discovered yet another setback: the captain and his crew had thrown much of the coal that had been purchased in Crete into the sea overnight. Lacking the fuel to make it to Palestine, the refugees had no choice but to point the Atlantic eastward toward British-occupied Cyprus, despite fears that they would be arrested as illegal immigrants.

After realizing that the Atlantic did not even have enough coal to make it to Cyprus, the Jews stripped the vessel of any wooden objects that could be burned for fuel. They removed planks, railings, partitions, bunks, floorboards, doors, and paneling. They tore down all but one of the masts and sawed them into pieces. They dismantled tables and even broke apart an old piano. When they were done, there was no wood left on the ship’s bow.

By this time, the passengers were just as emaciated as the boat. Since they had boarded the Atlantic two months earlier, the refugees’ food had been limited to a watery soup at noon and tea twice a day. They would sometimes receive a small ration of vegetables, cheese, and bread for dinner, but often had to make do with moldy biscuits. Many were already malnourished and weakened from the earlier legs of the journey, and lacked the strength to continue living. The cramped conditions and poor sanitation also led to outbreaks of diarrhea, dysentery, and typhus. Death became a part of daily life aboard the Atlantic.

On November 12, a stripped and powerless Atlantic drifted into the waters surrounding Cyprus. The immobile boat was intercepted by a British motor launch and towed to the port of Limassol, where it would stay until Great Britain could figure out what to do with its passengers. The British found themselves between a rock and a hard place. They were alarmed by the poor health of the refugees, who were suffering from exposure, exhaustion, and starvation, but could not allow them to disembark, because Cyprus lacked the infrastructure to care for them. At the same time, the British could not deport the Jews, because they had yet to break any laws. The British ultimately decided to escort the Atlantic toward Haifa. The refugees had no way of knowing that they were being taken to Palestine only so they could be arrested as illegal immigrants once they arrived.

Ten days after the Atlantic arrived in Cyprian waters, a British captain and an armed military guard boarded it to sail it to Palestine. The British were shocked by the condition of the overcrowded vessel, which was listing so much that forty portholes on one side were submerged underwater. To make matters even worse, there were only enough lifeboats for one hundred people, and about a third of the 1,800 passengers did not have life vests. The British loaded the Atlantic with food, coal, and other supplies—albeit at exorbitant prices that required many of the refugees to sacrifice the little jewelry that had survived the earlier extortions. The Atlantic got under way at five the next morning, escorted by a convoy of British warships and minesweepers.

On the next morning, November 24, 1940, the Jewish refugees finally set their eyes on the Promised Land. Almost a full year had passed since the first group of Jews aided by Storfer’s committee had left Vienna. As the sunrise illuminated the bay of Haifa, the historic mountain range known collectively as Mount Carmel became visible in the background. “From the Atlantic’s ghostly deck, green Mount Carmel was like a glimpse of heaven,” one passenger later recalled.29

The refugees shouted with joy. Just as when they had left Bratislava almost three months earlier, they joined together to tearfully sing “Hatikvah.” This time, their joyful songs were accompanied by harmonicas and violins, perhaps including Erich Weininger’s Violin.

The British anchored the Atlantic just outside the port of Haifa. The Atlantic was reunited with the Pacific and Milos, which had both arrived at the beginning of the month. Near the two empty ships was a large ocean liner named the Patria. Around noon, two British officers boarded the Atlantic and announced that all of the passengers would join their counterparts from the Pacific and Milos on the Patria. Later, civil servants boarded the Atlantic to question the passengers, search and seize their belongings, and give them forms to complete. The refugees naturally asked why they were not being allowed to come ashore. Were they being quarantined? Was the sequestration just a temporary measure until they could be accommodated on land? From the noncommittal answers they received, the Jews finally began to suspect that they would not be allowed to disembark in Haifa.

Palestine

The presence of the Pacific, Milos, and now the Atlantic in Palestinian waters presented a considerable problem for Great Britain. The rise of anti-Semitism in Germany and Austria had led to a dramatic increase in Jewish immigration to Palestine, which in turn had instigated a violent three-year Arab revolt. To placate the Palestinian Arabs and their allies in the region, Great Britain in the White Paper of 1939 had drastically cut the number of Jews who could immigrate to Palestine in any given year. But these quotas had not provided the deterrence they had hoped for. Hundreds of Jewish refugees had continued to land in Palestine every month.

Great Britain had decided to put an end to illegal immigration once and for all. Beginning in January 1940, the naval Contraband Control Service had started to seize all ships carrying illegal immigrants before they reached Palestine. The captain, crew, and passengers of such vessels were brought to Palestine and placed in internment camps, but were ultimately released within a matter of months. The aggressive tactics seemed to have worked: by August 1940, the Mediterranean Sea was free of refugee ships.

The British authorities were therefore alarmed on September 17, 1940, when they received a telegram from their embassy in Bucharest, Romania, informing them that the Atlantic, Pacific, and Milos were preparing to leave the port of Tulcea with several thousand illegal immigrants. The British realized that their threats to impound the ships offered little deterrent. Immigrants would simply arrive on derelict vessels such as the Atlantic, Pacific, and Milos that were practically worthless. The warnings that refugees would be detained were also not working. The Jews were willing to risk being interned for a few months because they knew they would eventually be released into Palestine. Great Britain decided to send a strong message by immediately deporting all illegal immigrants elsewhere and making it known that they would never be permitted to return to Palestine.

To prevent the newest refugees from even setting foot in Palestine, it was decided that they would be transferred directly to the Patria. The 15,000-ton ocean liner was originally designed to carry 805 passengers, including a crew of 130. It was now being reclassified as a troop transport, which would allow it to hold 1,800 people without increasing the number of lifeboats.

When the Pacific arrived in Palestinian waters on November 1, it was intercepted by a naval patrol and escorted toward Haifa, where the 962 refugees who had survived the voyage were transferred to the Patria. The Milos received the same treatment two days later, at which time its 709 refugees were taken to the Patria. It was decided that when the Atlantic arrived, eight hundred of its passengers would be assigned to the Patria—bringing its total contingent to a whopping 2,500. The remaining one thousand Jews aboard the Atlantic would be transferred to another vessel, the Verbena.

But where would the refugees be taken? Jamaica, Africa, Cyprus, Australia, and even Great Britain were considered as possible internment locations for the illegal immigrants. All were ultimately rejected on logistical or political grounds. The British finally decided to take the 1,700 Jews from the Pacific and Milos to their colony on Mauritius, an island in the Indian Ocean five hundred miles east of Madagascar. The 1,800 refugees from the Atlantic would continue on to Trinidad.

On the morning of November 25, 1940, one day after the Atlantic arrived in Palestinian waters, the British authorities began to transfer its passengers to the Patria. They started with women and children. By 9 a.m., 134 refugees had been transferred and another transport was just shoving off. Erich was on that dinghy and was heading toward the Patria.

Suddenly, there was a violent explosion. Erich watched in horror as an intense flame shot out the side of the Patria. The enormous ship capsized immediately. It sank within fifteen minutes.

The explosion was caused by a bomb that had been planted by Haganah agents from Palestine who had secretly boarded after learning of the British plan to deport the Jewish refugees. They knew that the forced expatriation of 3,500 immigrants would discourage other imperiled Jews from leaving Nazi-occupied Europe. They were determined to not let his happen. The Haganah snuck a bomb into the engine room in the hopes of disabling the Patria. If the ship was immobilized, they hypothesized, the British would have no choice but to allow its passengers to disembark in Palestine.

But the Haganah underestimated the bomb’s power and overestimated the integrity of the Patria’s hull. Instead of merely damaging the engine, the explosion tore a large hole in the side of the ship. The majority of the passengers found safety by clinging to the wreckage until they could be rescued, or by swimming to the long jetty that protected Haifa’s harbor. But more than two hundred refugees died, along with fifty crew members and policemen. Some were trapped in their cabins. Some got stuck in the narrow portholes when they tried to escape. Others fell off the deck and were sucked underwater by the downdraft of the rapidly sinking ship.

The survivors of the Patria disaster were taken to the Atlit detainee camp, which Great Britain had established just a few years earlier to incarcerate illegal immigrants. Located twelve miles south of Haifa, Atlit was surrounded by barbed-wire fences and watchtowers. More barbed wire divided the camp into several sections that separated the survivors of the Patria from the former passengers of the Atlantic. The refugees were given blankets and cramped shelter inside the camp’s hundred Nissen huts.

The British authorities now had an even bigger problem on their hands: what should they do with the 3,300 refugees who were now on Palestinian land? After several days of internal debates, Great Britain yielded to pressure from Jewish groups in Palestine and the United States and announced a compromise. Those who had been on board the Patria when it sank would be granted amnesty, released from Atlit, and allowed to stay in Palestine. The former passengers of the Atlantic, however, would be sent to Mauritius as quickly as possible.

On December 8, the British instructed the refugees from the Atlantic to deliver their packed bags by midnight and be prepared to wake at five the next morning for transport. Although the Jews were not told where they were going, they suspected that they were being expelled from Palestine. The Jewish auxiliary police who helped guard Atlit encouraged the refugees to resist, assuring them that they had the support of the entire Jewish community in Palestine. The refugees devised a plan of nonviolent protest in which they would leave their bags unpacked, lock themselves in their huts, sleep naked, and refuse to leave their beds in the morning.

Midnight came and went without any luggage appearing at the depot. The commandant announced that any missing luggage would be left behind. This, too, failed to produce any response.

The silence, combined with Jewish work strikes throughout Palestine protesting the impending deportations, convinced the British authorities that the refugees would not leave Atlit quietly. Overnight, police wagons and armored cars rolled into the camp. Armed British soldiers surrounded the barbed-wire perimeter and posted machine guns in the camp’s corners. They replaced the Jewish auxiliary police with a special squad of Palestinian police officers who were known for their brutality. Finally, they entered the camp, fortified with clubs and metal helmets.

The order to wake for departure was given at 5 a.m. Nobody moved. The police waited fifteen minutes, and then started advancing from hut to hut. They broke open doors, overturned cots, and ripped blankets off the naked refugees. As soon as they moved on to the next hut, the protesters went back to bed.

An hour later, the police made a second round. This time they bludgeoned whoever refused to rise. Those who offered the most resistance were dragged outside and beaten unconscious. They were wrapped in blankets, dragged on the ground, and tossed into the backs of the trucks that had arrived throughout the night. Others were carried to cars and buses on stretchers with bleeding wounds and broken bones. Confusion reigned as the unarmed refugees tried to fight back, shouting, cursing, and crying in protest. Some courageous young men continued the protest by running around the camp naked. They were chased down and beaten until they collapsed into pools of their own blood. “Look at the bloody Jews!” the policemen taunted.30 The abuse that the Jews were enduring in Palestine was not very different from the cruel treatment they had thought they had left behind in Europe.

Of all the injustices the Jews had suffered, this was the worst. For those who, like Erich, had suffered in Dachau and Buchenwald only to endure captivity in Bratislava before making the arduous trek to the Promised Land, the thought of being deported was too much to bear. Everyone was crying. “At least let me die here,” pleaded one elderly refugee.31

As Erich was being corralled toward the military transport, British soldiers repeatedly tried to steal his violin. Every time a soldier got close, Erich threw the instrument over a separation fence to detainees in the neighboring yard. Whenever a British soldier on the other side would try to seize the violin, it was thrown back to Erich. The British never got the instrument. Erich eventually disappeared into one of the trucks with the violin that had accompanied him from Vienna to Dachau, Buchenwald, Bratislava, and Atlit.

The Jews were taken back to Haifa, where they were put aboard two Dutch steamers that Great Britain had requisitioned to carry them to Mauritius.

Palestine to Mauritius

The Johan de Witt and Nieuw Zeeland left Haifa on December 9, 1940, with Erich and 1,600 other Jewish refugees on board. Escorted by two British warships that zigzagged along while sweeping for mines, they sailed toward Port Said, Egypt. The Jews had still not been told where they were going, and had no way of seeing for themselves. The portholes were shut, and although the holds’ hatches had been removed to compensate for the closed windows, the refugees were not allowed on deck. Their only clue that they were even under way was the drone of the engines.

The Dutch steamers were former luxury liners that had been converted into troop carriers. Both had several hundred cabins. These were left mostly empty except for a few that were occupied by elderly refugees, women with children, and Palestinian police officers. While the open dormitories in which the majority of the Jews traveled would have hardly qualified as luxurious, they represented a significant upgrade from the accommodations aboard the Atlantic. The Jews had hammocks for sleeping, shelves for storing their belongings, and even benches and tables where they could sit and eat.

By the third day of the voyage, the Johan de Witt and Nieuw Zeeland had passed through the Suez Canal and had reached the Red Sea. The refugees were finally allowed on deck, but only for limited times. Eventually, as the temperatures in the hold grew stifling, the Jews were permitted to not only sleep on the deck but also use the ships’ swimming pools. The portholes and the hatches were left open during the day, but were closed at night for blackouts.

The ships arrived in Port Louis, Mauritius, on December 26, 1940, after two and a half weeks at sea. The Jews were immediately struck by the island’s tropical beauty. “Mauritius, rising in the distance out of the calm Indian Ocean, appeared more and more enchanting the closer we approached,” one refugee later recalled. “The island, surrounded by lagoons of a blue I had never seen before, was fringed with thick green vegetation and tall, exotic coconut palms behind which rose hazy, purplish hills. Here was something new, something totally different from anything I’d ever known, so exciting I felt my pulse race; my eyes welled up with tears.”32

The Jews were taken by bus to the town of Beau Bassin. Along the way, they continued to be struck by the beauty of the island and the friendly welcome they received from its residents, who threw flowers as they passed by. The reception was more befitting to war heroes returning from battle than to destitute refugees.

It was therefore quite a shock when the buses reached their destination. “There we had the biggest surprise of our entire voyage, which had contained quite a few during the past four months,” one refugee recorded in his diary. “The bus stopped in front of a small one-story building. We crossed a porch and entered a large yard where we saw two enormous cellblocks, each 90 to 100 meters long, with barred windows—A PRISON!”33 This prison was to be their home for the next four and a half years.

Mauritius

The island of Mauritius was first visited by Arab sailors in the Middle Ages, but was rediscovered by Portuguese en route to India in 1507. It was later settled by the Dutch, who named the island after Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange, and used as a naval base. It was the Dutch who discovered the now-extinct dodo bird on Mauritius. France took control of the island in the early eighteenth century, but lost it to England in the Napoleonic Wars. Great Britain had ruled the island and its valuable sugarcane fields ever since.

Five miles south of the Mauritian capital of Port Louis is the Beau Bassin Prison. A maximum-security compound that dates back to the nineteenth century, the prison was once the home to thieves and murderers. The British had planned to intern fascist political prisoners there during World War II. Instead, the prison grounds became home to 1,600 Jewish refugees.

By the time the Jews arrived at the Beau Bassin Prison, many were suffering from a variety of physical and mental illnesses, ranging from malnutrition, dysentery, and diarrhea to psychological exhaustion and depression from their yearlong ordeal. Initially, the most critical of these maladies was the typhoid fever that had gone untreated throughout their flight from Europe. As soon as the typhoid epidemic came under control, an outbreak of malaria took its place. Lacking adequate medical facilities and medication, twenty-eight refugees died within the first five weeks.

The males were confined to the Beau Bassin Prison. The men from Prague and Danzig moved into Block A, while Erich and the other men from Vienna occupied Block B. In each block, endless rows of heavy doors led to inhospitable cells. Each cell was approximately twelve feet long and nine feet wide and contained only a hammock, a shelf, and a barred window. There was no electricity. The men were, however, free to wander around the cell blocks. The door locks had been removed. The men were even able to enjoy a large prison yard that included trees, grass, and flower beds.

On the other side of the fifteen-foot stone wall that surrounded the prison was a hastily constructed camp for the women and children. The camp was enclosed by a barbed-wire fence. When the refugees first arrived, the construction was still ongoing. The camp eventually included thirty wooden huts with corrugated iron roofs. Each hut could hold twenty-five to thirty women and children.

The refugees quickly fell into a predictable daily routine. They would rise at 7 a.m. to drink their morning tea and receive their daily ration of bread, margarine, and sugar. Lunch took place between 12:30 and 1 p.m., and often consisted of fresh meat, corned beef, or canned salmon, along with unfamiliar local ingredients such as sweet potatoes, dried beans, and breadfruit. At 7 p.m., the refugees would eat soup and jam for dinner. Between their meals, the Jews under the age of thirty-five would do light chores such as cooking, cleaning, gardening, and maintenance. It was not long before craftsmen opened workshops that provided their fellow refugees with essential items such as clothes, shoes, and custom-made furniture for their barracks. Eventually, the detainees even earned small allowances for their chores and wares, many of which were sold in Mauritius and abroad.

In their free time, the refugees engaged in a wide variety of educational, cultural, and social activities. They founded a school, where the children were taught English, German, Hebrew, religion, geography, history, mathematics, science, music, and art. The adults organized similar classes for themselves, and also studied Jewish history and Zionism. They read the local newspapers, as well as books and magazines that they received from the Mauritian police department and Jewish communities in Palestine and South Africa. They held literary and poetry competitions, as well as tournaments for cards and chess. For a while, they even published a daily newsletter, Camp News. Artists organized exhibitions, and playwrights and actors staged theatrical performances, puppet shows, children’s plays, and musical revues. There were also dances, cabaret evenings, and Hanukkah parties. Such events helped to provide comfort and raise the morale of the detainees throughout their prolonged internment.

Not surprisingly, music played a major role in this vibrant cultural community. In February 1941, the residents of Mauritius donated pianos, violins, accordions, and other instruments to the refugees. Erich, of course, still had the violin that he had brought from Vienna. The musicians in the camp entertained themselves and their fellow detainees by transcribing Beethoven piano sonatas and performing them as string quartets. They repaid the generosity of their Mauritian benefactors by forming an orchestra that accompanied an amateur performance of Puccini’s opera La Bohème in nearby Rose Hill that July. Twelve hundred detainees attended one of the performances. It was the first time many of them left the confines of the Beau Bassin Prison.

Erich and other refugee musicians regularly performed in the Beau Bassin Boys, a jazz orchestra formed by pianist and fellow detainee Fritz “Papa” Haas. In their first year in Mauritius, the Beau Bassin Boys provided the music for an English-language revue that consisted of songs, folk dances, and satirical poems about camp life. The vaudeville show was a big hit among those in attendance, which included the British commander of the camp and his wife, as well as members of the press. The Beau Bassin Boys were so popular in the prison camp that Papa Haas is often the first name that survivors recall when discussing their lives in Mauritius.

The popularity of the Beau Bassin Boys extended well beyond the prison walls. Their performances were broadcast over the radio and they were even allowed to leave the prison several times a week for performances. Dressed in matching white shirts and black pants, black bow ties with red cummerbunds, and white dinner jackets, the Beau Bassin Boys played at dances, weddings, and other official and festive events throughout Mauritius, including parties hosted by the island’s governor. These performances gave the musicians their only moments of freedom. The frequent invitations to play elsewhere on the island provided precious opportunities to leave the Beau Bassin Prison.

When they first arrived in Mauritius, the Jews were not allowed to pass through the heavily guarded iron gate that separated the men from the women and children. These restrictions were gradually relaxed. Within the first year, married women were permitted to bring their children to visit their husbands during limited hours. Then all refugees were given the opportunity to intermingle for four hours a day in the recreation grounds that surrounded the prison. By the time the detainees finally left Mauritius in 1945, they were able to move freely between the men’s prison and the women’s camp.

Once the refugees were no longer separated by gender, old relationships were rekindled and new ones began. The September 13, 1942, issue of Camp News teasingly reported that Erich had “succumbed to family life” by marrying Ruth Rosenthal,34 whose family had left Danzig with financial assistance from relatives in the United States. The Beau Bassin Boys provided the music for Erich’s wedding, which was one of thirty marriages that took place in the prison courtyard by the end of 1942. One year later, Erich’s son Ze’ev became one of sixty Jewish children who were born in Mauritius.

Although Beau Bassin was nothing like a Nazi concentration camp, life within the prison was still dreary. Throughout their lengthy internment, the refugees yearned for freedom. They resented being sequestered behind prison walls, under the watchful eyes of a hundred members of the prison administration, staff, and guards. They felt oppressed by the limited opportunities to leave the camp. Worst of all was their frustration over having been stripped of their civil rights and incarcerated for an indefinite period of time with no opportunities to defend themselves or appeal their confinement through any legal system.

The refugees also continued to suffer from malaria. At some points during their detention, as many as 40 to 50 percent of them had the disease. While malaria was not the primary cause of many deaths, its chronic high fevers did fatally weaken the elderly and those with heart conditions. Lacking adequate medical care to deal with malaria and other illnesses such as malnutrition, dysentery, and cardiovascular diseases, 127 Jewish refugees died in Mauritius. This included Erich’s father-in-law, who died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-five.

It was not until January 1945—four years after the refugees had been brought to Mauritius—that the British government finally changed its mind about their immigration to Palestine. Bowing at last to international pressure, Great Britain decided to include the Mauritian detainees in the 10,300 emigrants who would be admitted into Palestine that year.

Given the difficulties of traveling during the war—several ships had been torpedoed near Mauritius—the British could not pledge that the relocation would be swift. In the end, eight months would transpire between when the British decided to send the refugees back to Palestine and when they were actually able to fulfill that promise. One plan was to give the Jews passage aboard a convoy of warships that would be passing through Mauritius in May. This was abandoned when a polio epidemic broke out on the island. The refugees were quarantined and their departure was canceled.

They would not get under way until August 11, 1945. By this time, World War II had ended and the Jews had learned of the horrible genocide that had claimed the lives of countless relatives and friends they had left behind in Europe. Out of the 1,581 Jewish refugees who had been on board the Atlantic, 1,307 were still living on Mauritius in 1945. In addition to those who had died, several dozen emigrants had left to fight in the war. The remaining refugees joined several hundred British soldiers who were returning from India aboard the RMS Franconia.

Israel

On August 26, 1945, almost six years after leaving Vienna for Palestine, the refugees returned to Haifa. This time they would bypass Atlit and proceed directly to their predetermined housing arrangements. Some would stay with family members who were already in Palestine or would settle into one of the collective agricultural communities. About four hundred of them would move into houses that had been built for them in Haifa, Tel Aviv, and the northern coastal city of Nahariya. A few dozen who had opted to return to Europe were taken to a transit camp south of Gaza.

Erich was among the immigrants who settled in Nahariya. He renewed his career as a butcher, but still continued to play the violin that had accompanied him on his astonishing odyssey from Vienna to Dachau and Buchenwald, from Bratislava to Palestine and then Mauritius, and finally back to Palestine. He would often invite a pianist and a drummer he had met in Nahariya over to his home for intimate evenings of playing traditional Austrian folk music and waltzes.

Erich returned to Austria a few times for brief visits. He gave serious consideration to murdering the former friend who had informed on his father, but was talked out of it. “Don’t do it,” Erich’s friends pleaded with him. “They’ll throw you in jail for the rest of your life. You’ve already spent enough time in prison.”35

Erich died in 1988, at the age of seventy-six. His violin was passed down to his son Ze’ev, who lived in Germany, and his daughter Tova, who still lived in Israel. It stayed with Tova until 2012, when she started considering selling it. Her son took the violin to Tel Aviv to see how much the instrument was worth. He quickly learned that there was only one person who could appraise it: Amnon Weinstein. The violin was damaged from being played outside in Mauritius’s tropical heat and had little monetary value, but Amnon immediately recognized the instrument’s historical significance. He agreed to restore the violin for free. All he asked in return was permission to maintain Erich Weininger’s Violin as one of the Violins of Hope.