In one of the rooms in Marienburg Castle, in Feldiora, Generals von Falkenhayn and Goldbach stood at a table, talking and occasionally pointing to a map on the table. Accompanying Goldbach, the commander of the Austrian 71st Division, was Major Rudolf Kiszling, his division’s general staff officer (chief of staff). In the distance, the sounds of battle echoed: artillery, machine-gun, and small-arms firing. The noise came from Brasov, a few miles to the south, where sporadic gunfire met the German units entering the city. Beyond the city, larger battles raged as the Austrians and Germans snaked into the mountains, hoping to cut off the fleeing Romanians before they got to the security of the fortified areas on their side of the border. In the likely event that von Falkenhayn’s exhausted soldiers could not rout the Romanians from their prepared positions, the 9th Army would have to launch a breakout campaign. Von Falkenhayn wanted to discuss this course of action with Goldbach. Before the war, the Austrian had served as chief of staff of the XII Army Corps, garrisoned in Sibiu. Because he knew the area well, the Austrian High Command had sent him back to Transylvania.1

Both Austrian and German High Commands thought in terms of a decisive battle after the mountain breakout that would lead to a Romanian capitulation. By definition, such a task meant cutting off the Romanian forces in Walachia so they could not retreat, facilitating their annihilation. From this perspective, the best crossing point was the Oitoz Pass to Ocna, where an invasion force could then march across Walachia to link up with von Mackensen’s army after it had crossed from Cernavoda on the Danube. This plan offered the possibility catching the most of the enemy’s armed forces. If one crossed from the west – for example, from the Szurduk Pass or the Red Tower Pass – fewer enemy forces were likely to be caught in the trap.

Von Falkenhayn wanted to sound out the Austrian general about the geography of the region’s mountains and passes. Several issues had to be considered in connection with a breakthrough. First was the potential for staging a large operation on the Transylvanian side of the mountains behind each possible crossing point; second, the width of the mountain girdle; third, the height and negotiability of the pass itself; and fourth, the potential for decisive results once clear of the mountains. Von Falkenhayn had apparently ruled out the eastern passes. The most significant deterrents to their use were the invaders’ vulnerability to counterattack from the Russians in the Bucovina and northern Moldavia once they exited the mountains and the fact that the exit routes from all the eastern passes led in the opposite direction from von Mackensen’s forces in the Dobrogea and Bulgaria.

More promising although not without drawbacks were the southern passes, from those near Brasov at the eastern apex of Siebenbürgen to the Vulkan Pass at the western end of the region. The passes (Bran, Predeal, Bratocea, and Buzau) emanating from Brasov all start from that city, a common point, but they branch away like fingers on a hand as the roads head into the mountains. Between the increasingly divergent highways and intervening ranges of mountains, the units traversing this region could not provide mutual assistance, and once they exited the mountains on the Romanian side, the advancing columns would be widely separated, allowing the defeat of each in detail. To date, the Romanians had not demonstrated much skill in moving units rapidly, but the future was unknown, and bad weather in the passes could halt some of the German-Austrian columns, providing an opportunity that the Romanians could seize. The other two areas where there were passes over the mountains to the south – namely, the Vulkan and Szurduk Passes near Petrosani and the Red Tower Pass south of Sibiu – were forty-five miles apart. Passage through them had the same potential for defeat of the separated forces.

With the eastern passes eliminated, the route south over the mountains from Brasov toward Bucharest and the Danube offered the greatest potential for crushing the Romanian Army. Both the Austrian and German High Commands, as well as the headquarters of Army Front Archduke Karl, favored this approach. Balanced against this was the fact that this route was the one the Romanians expected their enemies to take, and they had accordingly constructed formidable defenses in the passes south of Brasov before the war started. Every piece of intelligence that came to the 9th Army indicated that the Romanians expected to hold on until the exhaustion of the Austro-German forces, their lack of proper winter equipment and training, and the inexorably worsening weather would stop them in their tracks south of Brasov. All these factors encouraged von Falkenhayn to look elsewhere for a breakout. The two critical factors that seem to have tipped the decision in favor of the westernmost mountain passes were the rapidly closing time frame and the railway situation.2

The Austrian engineers had demolished the railroads in their retreat into central Transylvania, and although they were now working diligently to repair them, the closest railheads to the Red Tower Pass and Brasov were miles away at Sibiu and Sighisoara, respectively, undermining their potential as staging areas for an advance south.3 Restoration was going to take a while. This meant that for now, draft animals (of which there was a shortage) had to haul all equipment and supplies for a further six or seven days from the railheads just to reach the passes below Brasov. Reinforcements and newly arrived units with all their equipment and supplies would have to march that distance on foot. At the western end of the mountains near the Szurduk and Vulkan Passes, the working railroad coming from Hungary extended to Livadia, one day’s march from Petrosani. The Austrians expected to have the spur from Livadia to Petrosani reopened at any moment. From there it took another day to cross the Szurduk or Vulkan Passes into Romania, or a total of two days march at worst if the repairs were not effected. Snow would shut down the Vulkan Pass once winter arrived, but its effect on the nearby Szurduk Pass, at a much lower elevation, would be far less. With weather, equipment, and the logistical infrastructure constituting the key factors in von Falkenhayn’s calculations, the fact that his divisions could march the twenty miles through the Szurduk and Vulkan Passes in one night assumed major importance.

Goldbach and von Falkenhayn discussed all the passes and routes in great detail on the morning of 9 October. Based on his extensive firsthand knowledge, Goldbach recommended that von Falkenhayn make his breakout through the Szurduk-Vulkan Passes.4 Forgoing the potentially greater victory inherent in a breakout from the Brasov area, the German commander chose to settle for the more modest but also more certain results that crossing in the Szurduk Pass area seemed to promise.

On the 12th, he explained his rationale to Ludendorff, ruling out one by one all of the southern passes except the Szurduk. The Austrian 144th Infantry Brigade was already there with three mountain artillery batteries, and von Falkenhayn told Ludendorff that he wanted to divert the 11th Bavarian Infantry Division, coming from Russia, to the Szurduk Pass to conduct the breakthrough.5 He added that he planned keep pressure on the enemy all along the line of the Transylvanian Alps. He would not attempt crossing until the Alpine Corps had engaged the enemy forces in the Red Tower Pass, tying them up and preventing them from coming to the aid of their compatriots in the Szurduk Pass region.6 Von Hindenburg passed on a summary of von Falkenhayn’s intentions to Conrad the next day, saying he concurred.7

At this point a simple misunderstanding occurred that led to a kind of guerrilla warfare breaking out among the top headquarters, one that simmered for the rest of the campaign. The acrimony arose when the archduke’s headquarters, or at least von Seeckt, did not see the 9th Army memorandum to the OHL of 12 October in which von Falkenhayn stated his intent to cross the mountains in the Jiu Valley region, where the Szurduk Pass was located. Consequently, the guidance von Seeckt issued for planning the crossing remained unchanged from the substance of his conversations with the 9th Army staff on the 9th – namely, that the main thrust would emanate from the passes south of Brasov.8 When von Falkenhayn saw von Seeckt’s memorandum, he concluded that he had been deliberately ignored, and he angrily reiterated his intention of launching his main effort through the Szurduk Pass, identifying the units earmarked for the operation. Von Falkenhayn further insisted that he had to have all the heavy artillery for his plan to work.9 Before this memorandum arrived at either the archduke’s headquarters or Teschen, Conrad had likewise misinterpreted von Falkenhayn’s plans as spelled out in his memorandum of the 12th. The Austrian general told von Hindenburg he concurred with using the 11th Bavarian Division at both the Szurduk and Red Tower Passes, because an “offensive in both these locations will facilitate the attack that must occur near Brasov.” He thought the main thrust was still coming from Brasov to Bucharest.10 Von Hindenburg’s response was to agree, adding that “crossing the mountains south of Brasov must take place as soon as possible” and “this plan must not be changed, no matter what.”11 Neither the Austrian nor the German senior headquarters fully understood exactly what their chief subordinate in Transylvania planned.

Accompanied by von Seeckt, the archduke went to Brasov on 15 October to discuss the breakout plans with the 9th Army commander, in light of the confusion that had arisen between the two headquarters. Von Falkenhayn admitted that the Romanian defenses in the mountains had brought the Central Powers to a halt, and he briefed the royal visitor on his plans for attacking from the west, stressing the importance that the condition of the railroads had in forming his strategy. Unfortunately, the archduke came away with the wrong impression. He thought that von Falkenhayn still planned to attack all along the frontier, and wherever a hole opened, he would take advantage of it. Von Falkenhayn was noncommittal on that point, only saying that he thought the decisive battle of the campaign would occur near Ploesti once the forces had crossed the mountains and emerged on the plains of Walachia. That seemed quite sensible to the Austrian heir, who left with the understanding that the 9th Army still planned on breaking through south of Brasov.12

After deciding where to stage his breakthrough, von Falkenhayn had sent his divisions into the mountains east and south of Brasov both to keep pressure on the enemy and, with luck, to break through the Romanian defenses. He ordered Cavalry Corps Schmettow, consisting of the Austrian 1st Cavalry and the 71st Infantry Divisions, to the Oitoz Pass. Both divisions, with the 71st in the van, pushed through the pass to Poiana Sarata (Sómezö) on the Romanian side of the border. Two days later, the Romanian 37th Brigade (15th Division) and 2nd Cavalry Division attacked the overextended Austrians. Taking charge of the situation, the energetic Romanian General Eremia Grigorescu of the 15th Division rallied his men with the slogan “the enemy will not pass here.” The Romanians captured the Runcul Mare heights above the pass, threatening Goldbach’s lines of communication. Heroic efforts by the 82nd Austrian (Szekeler) Infantry Regiment salvaged the situation on the 25th, but the advance in the Oitoz Pass had come to a halt. Worn out, the Austrians fell back to a better position, having come tantalizingly close to breaking into Moldavia.13

A glimmer of hope came from the Austrian 8th Mountain Brigade of von Morgen’s I Reserve Corps, which took the town of Rucar, south of the Bran Pass, on the 14th by turning the flank of the defenders. Marching hard through rugged, roadless terrain, the Austrians caught the inexperienced Romanian 12th and 22nd Divisions by surprise. The victory opened the Bran Pass, where the 76th Reserve Division had been struggling. But efforts to press on faltered at Dragoslavele. Although the 9th Army was now in Romania, a tantalizing eight miles from Campulung, von Morgen’s corps would make little further progress for a month. To the east, the XXXIX Reserve Corps was stalled in the Predeal region and reported it could see no way in which the enemy position in the pass would fall soon.14

The operation in the Red Tower Pass to fix the Romanians in place, allowing a breakthrough at the Jiu Valley, started on 16 October, when Alpine Corps began its advance south down the Red Tower Pass to Romania. Von Falkenhayn had reinforced Krafft with two Austrian mountain brigades, the 2nd and the 10th, so the latter attacked on a wide front. The mission was to get to Curtea de Arges as rapidly as possible.15 On each of his flanks Krafft placed one of the Austrian brigades, the 10th (under Colonel Karl Korzer) on the west or right flank, the 2nd (under Colonel Karl Panzenböck) on the eastern or left flank. Krafft weighted his attack on the east side of the pass. Initially, the Bavarian Guard Regiment was to come down the middle of the pass to Caineni, then slip southeast across the Olt and over the mountain heights toward Titesti, and then move farther southeast toward Salatrucu. Once on the east side of the pass, they would join the Jäger Brigade (under von Tutschek and the 2nd Austrian Mountain Brigade). These units had orders to cross the Fagaras Alps via Marmunta and Zanoaga to Salatrucu. From there, they would advance toward Curtea de Arges.16 The mountains were as high as 7,500 feet.

The forces on both flanks initially made excellent progress. The 2nd Brigade covered forty miles in the first thirty hours, reaching Mount Furuntu. Next to them, just to their west, the Bavarian Jägers stormed the Moscovul massif (7,500 feet high) in thick fog, taking it in hand-to-hand fighting.17 On the far west flank, the 10th Brigade crossed Mount Robu. The Bavarian Guard Regiment slowly came down the Red Tower Pass, conducting frontal assaults that inched forward in the face of strong enemy resistance. Snow began falling on the 18th, and a heavy blanket of it fell on the 20th, which brought everything to a halt. The temperature fell to five degrees, and in some of the passes, the depth of the snow reached 4 to 5 feet. On the west flank, the hard going exhausted the 10th Mountain Brigade, and the 2nd Jäger Regiment had to relieve them on the 20th, just four days into the operation.18 In the Moscovul Gap, through which ran the lines of communication for the 2nd Mountain Brigade and the Bavarian Jäger Regiment, three feet of snow covered the ground, making movement impossible for pack animals and supply trains. The Bavarian Jägers had to form columns of human bearers from their reserve companies, and local inhabitants were pressed into service in order to reach the Austrians. Nonetheless, ammunition and food could not get through, and Panzenböck, whose lead units had crossed the ridge line into Walachia, had to call a halt and pull back to Mount Fruntu and finally to Poiana Lunga.19

A note of anxiety appeared in the 9th Army headquarters, although staff officers tried to reassure themselves that setbacks were temporary:

With the early onset of winter weather with its raging snowstorms and freezing cold, doubts have arisen whether it is possible to force the mountain passes along the border. The majority of the units have no training in mountain warfare, and only a tiny and shrinking portion are equipped for it. The outfitting of units with mountain artillery and pack trains is entirely inadequate. The resistance of the enemy, who enjoys the advantage of being on the gentler slope of the mountains with good communications and in entrenched positions, grows daily owing to the rapid arrival of reinforcements.

On the other hand, locals tell us that the real winter has yet to begin, and with the great confusion in the units of the Romanian Army, one can conclude that the defensive capability of the Romanians is not really that high.

It would be premature at this time, therefore, to dismiss efforts to force the border passes as having no chance of success.20

After waiting out the worst of the weather, the Austro-German forces resumed their drive. Within the Red Tower Pass, the steep, cliff-like walls reduced the options of the attacking forces to one: frontal assaults. East and west of the pass, the Romanians had constructed fortifications in the mountains. On the east side, their positions on the Bumbesti-Mormonta-Zanoaga line turned out to be the key ones, and after Mormonta was taken on the 28th, Zanoaga fell to the Bavarian Guard Regiment, costing the Romanians over 700 casualties and prisoners. Above the Red Tower Pass, within the woods and mountains, an opportunity existed to envelop the Romanians or to bypass them and later hit them from the rear. Everything moved in slow motion in the cold and snow, and the freezing temperatures at the higher altitudes during the night often caused as many casualties as did the enemy. On top of everything, the Romanians fought hard and tenaciously. In front of one enemy position, the Germans counted 89 dead. At Perisani, hand-to-hand combat resulted in only two prisoners; the rest of the Romanians fought to the end.21 One of the battle groups of the 23rd Division, Detachment Mihailescu, reported losing 2,000 men between 24 and 29 October.22 Near Poiana Spinului, Romanian rifle fire on 7 November claimed the life of Prince Heinrich of Bavaria, the popular leader of the III Battalion of the Guard Regiment who was conducting a personal reconnaissance of the front line. His last words came in response to the reproach that he had gone too far forward, to which he said “Noblesse oblige. I do not mean that with respect to my family but rather my duty as an officer.”23

Two days later, the Guards took the Mount Cozia position on the east edge of the Red Tower Pass, but further progress south remained glacial. The Romanian 7th Division arrived in the region around 20 November and brought the Germans to a halt north of the Caineni-Salatrucu highway. Farther to the east, the Jäger Brigade retook Salatrucu on 12 November.24

On the western side of the Red Tower Pass matters were at a standstill. The men of the hapless 10th Brigade had returned to the Ververita Crest from which the bad weather of 20 October had driven them, but they had yet to recross it. The Austrian High Command sent one of its leading mountain warfare experts from the Italian Front, Major General Ludwig Goiginger (1863–1931), to take over operations from Korzer. Goiginger brought with him the headquarters (but no units) of the 73rd Division and assumed command over the west bank of the Olt Valley.25 The Austrian alpine warfare expert now had under him the 10th Mountain Brigade and General Friedrich Freiherr von Pechmann’s (1862–1919) 15th Infantry Brigade, which had two regiments. Pechmann’s brigade came from the 8th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Division, which had arrived from the Somme region.26 On the east side of the valley, Krafft added the 216th Division, a brand-new one from Germany, but progress remained slow. On 12 November, the Jägers and the Guards crossed the Caineni-Salatrucu highway.27 Unhappy with the pace of the advance, Krafft told his subordinate commanders on the 13th to speed things up, claiming that there were some signs the enemy was cracking. On both the 14th and 16th, over a thousand Romanians were taken prisoner, bringing the total from 31 October to 15 November to 80 officers and 7,000 soldiers captured, along with twelve cannons and twenty machine guns.28 Nonetheless, Group Krafft had a long way to go before it emerged from the mountains.

On 16 October, the same day the Germans started moving south in the Red Tower Pass, an event of equal import occurred fifty miles to the south, in Peris, the site of the Romanian army’s headquarters. Around noon, a special train coming from Russia pulled into the siding at the headquarters and discharged a few passengers. One stood out immediately. At 250 pounds, Major General Henri-Mathias Berthelot of the French Army was almost as wide as he was tall. Prime Minister Bratianu, who awaited him on the platform, greeted him in his native tongue and made a surprising offer. The Romanians proposed to make Berthelot chief of staff of their army. When Berthelot demurred, the prime minister took him to meet the king, who, after a few minutes of pleasantries, repeated Bratianu’s proposal. This time the French general said, “I prefer to be among you without any special title – [with] just a willingness to help.” Later that day, Berthelot traveled to Bucharest to rejoin the several hundred officers and men of the French military mission. And that evening he met Queen Marie in a private audience. The two instantly hit it off. The queen’s positive attitude and strength moved the French general; the king and the staff at the Peris headquarters had left the exact opposite impression, that their morale and spirit had collapsed.29

The traumatic loss of Turtucaia and the sound of enemy guns in Bucharest at the onset of the war had led Bratianu and former ministers Take Ionesco (1858–1922), and Nicolae Filipescu (1862–1916) to urge King Ferdinand to ask the French government to send an experienced leader to the Romanian High Command as a liaison officer.30 Bratianu wanted a confidant through whom he could influence operations. Before the war began, the prime minister had talked to the French government about sending a training team once mobilization began. Ostensibly the role of the group would have been to share France’s hard-won military expertise, but Bratianu had really wanted a French general to take the role of chief of staff of the army, a plan side-tracked by the press of events.

The unexpected setbacks in the Dobrogea had prompted Bratianu to renew his approach to the French, this time with some urgency; with a different ambassador, the process of selecting and sending the mission began. Meanwhile, the additional reversals in Transylvania had increased the pressure on the Romanian government. At the daily briefing on 14 October, the king told Iliescu that the opposition, primarily led by Ionescu and his party, had called for major changes at the head of the military. They wanted to see Averescu appointed commander in chief, but the king had bluntly refused that request. He did tell Iliescu, however, that public opinion might compel him to appoint Averescu chief of staff.31

Romania’s request for training assistance from the French had generated enormous concern in Petrograd. The exchange of military attachés was routine, but training missions, at least before the war, were usually viewed as vehicles of military imperialism. The Russians had not reacted well to the prewar penetration of Turkey by German, British, and French training missions,32 and the sudden appearance of the Allied Army of the Orient in Thessalonica in 1915 in what amounted to Russia’s backyard had come as an unpleasant surprise to the Russian government. The antics of Sarrail, the army’s openly republican commander, in supporting Greek Prime Minister Venizelos in what amounted to a revolution against his own king set the Russians on edge. They did not mind seeing the pro-German monarch Constantine pushed aside; what troubled them was that it was Venizelos who was pushing. His open lust for Constantinople formed an integral part of his irredentist notion of Megalia, or Greater Greece, which clashed with Russian aspirations in the Balkans. The Russians had no intentions of allowing the Greeks or anyone else to enter Constantinople, and they sent a division to Salonika to make that point.33 Between Sarrail’s support for Venizelos and the French willingness to send a mission to Romania, the Russians had to wonder if the Crimean coalition was being revived to strip them of the ultimate prize. The Russians had their treaty with the Entente, but France had already demonstrated an icy realpolitik during the negotiations that led to Romania’s joining the Allies, which revealed a willingness to view treaties as scraps of paper.34

From a military standpoint, sending a team from neighboring Russia once Romania had entered the war made far more sense than sending one from distant France. There was not even a direct connection from France, only a lengthy, hazardous, and tortuous journey via sea and rail through neutral nations and across European Russia. Moreover, the military accord that Romania had signed with the Allies called for the Russian and Romanian armies to fight side by side. Nonetheless, the impeccable logic that dictated that a military training mission was better suited to Russia could not shake the inborn Romanian credo that Russian assistance would become Russian domination.35

Generalissimo Joffre personally selected Berthelot to head the mission and brought him to Chantilly on 20 September to tell him of his appointment. The two knew each other well from Berthelot’s service as Joffre’s assistant chief of staff during the Marne Campaign. A mountain of a man, Berthelot radiated strength and remained calm in the worst situations. His immense size fooled people; his stamina was as legendary as his appetite. “The tendency was to be so overwhelmed by his bulk,” wrote Lieutenant Edward Spears, an English liaison to Joffre’s headquarters in 1914, “that his extremely clever quick eyes escaped notice at first.”36 From staff work he had gone on to command a division and then a corps, leading the XXXII Corps through the hardest fighting at Verdun. Joffre warned Berthelot that he could expect difficulties from the Russians, who would look at the French effort with disapproval. In turn, Berthelot was “to be suspicious of them.” As far as the Romanians went, Joffre urged delicacy and noted it would be “necessary first to win over their confidence and their hearts.”37

Berthelot and his team of 400 officers and 1,200 soldiers left France on 1 October, sailing to Norway and then traveling via train through Sweden to Russia. In St. Petersburg, he met with Boris Stürmer (1848–1917). The ineffective prime minister’s defeatist attitude shocked and disappointed the Frenchman. At Moghilev, the location of Russian field headquarters, Stavka, Berthelot met with both Alekseyev and Tsar Nicholas II. French General Pierre Janin (1862–1946), Joffre’s liaison at Stavka, played escort. Berthelot thought his audience with Alexseyev amounted to an interrogation. The Russian general wanted to know everything about the French mission, from its size to its plans. Berthelot said he had nothing to hide and shared those details with the Russian. Then Alexseyev spoke, briefing Berthelot about the extended borders of Romania and the difficulty the Romanians were having, adding that they could expect no help from the Russians. Alexseyev said he had already sent some divisions to help them against the Bulgarians, but the Romanians had performed poorly. “There is but one possible defense line,” said Alexseyev, pointing to a map: “the line of the Sereth [River]!” Stunned, Berthelot remonstrated that attacking with everything the Romanians had in both Transylvania and Bulgaria offered the best solution. Alexseyev did not reply. Instead, he introduced General Mikhail Beliaev (1863–1918), a former chief of the general staff, who, Alexseyev said, “was forming a mission for Romania that was analogous to mine.”38

That marked the end of the meeting, but as soon as they were alone, Berthelot grabbed Janin and demanded, “What kind of games are they playing?” Janin defended Alexseyev, claiming that he was an honest man and that there was no better choice than Beliaev. Later that evening Berthelot had a tête-à-tête with Tsar Nicholas, who said to “tell King Ferdinand that I stand behind him with my armies, all my armies, and that I will support him to my last man and my last kopeck.”39

Berthelot wasted no time getting to work after he had arrived in Romania. The day after his arrival, he appeared at King Ferdinand’s daily operational briefing at Peris. Berthelot had already dispatched several of his officers to the front, ordering them to get back to him that night with their impressions. After listening to his officers, Berthelot recognized that the Romanian forces were exhausted. They had lost the initiative, and their operations amounted to little more than reacting to German, Austrian, and Bulgarian probes. Strung out along the borders north and south, they could meet crises only by using their interior railroads to transfer forces here and there to prevent potential breakthroughs. Berthelot concluded that the Romanians needed some relief and had to form a separate reserve that could be committed at any decisive time without running the risk of denuding another part of the front. Using interior lines helped greatly, but that meant that to respond to a threat in one area, another had to be left unguarded, and if the transport system broke down, disaster would ensue. Berthelot decided that he had to get the Romanians to stop retreating; they had to halt in place and stop the enemy at all costs.40 Once they had stabilized the lines and formed a reserve, they could return to the attack.

The next day he told King Ferdinand what he planned to do over the next few weeks. He handed the king a memorandum calling for a small offensive in Transylvania in order to establish a secure area around Brasov and the upper Olt Valley. The next priority was to organize defense lines in the Dobrogea. Finally, the Romanians had to destroy the enemy’s bridging equipment on the Danube. Berthelot told the king he wanted to detail a team of French officers to each Romanian army: an artilleryman, an infantryman, and a machine-gun specialist. He asked if he could assign an officer to each staff section within the Romanian general headquarters at Peris, and he placed a few officers in the War Ministry at Bucharest. He made Colonel (later general) Charles-Ernst Vouillemin (1865–1954) the inspector of artillery, and Colonel Leon Steghens the inspector of heavy artillery. A week later, Berthelot added a French liaison officer to each Romanian army, so that officer could report directly to the king and the staff sections at Peris. The king was satisfied with the plan and agreed to the arrangements the next day.41

On the 20th, Berthelot went to Buzau to visit Averescu’s headquarters. The 2nd Army was being pushed hard in the passes south of Brasov. Averescu’s reports had hinted at calamity unless he received more divisions, and Berthelot wanted to see matters firsthand. The two generals met in a rail car at Buzau, and Berthelot took an instant dislike to the Romanian. He thought that Averescu complained incessantly, insisting that he had not been given the necessary resources to conduct an offensive. Berthelot listened, but afterward informed Iliescu of his unpleasant impression. Berthelot said that it seemed that nothing would ever suit Averescu. Iliescu was no fan of Averescu and was all too happy to agree. Berthelot then briefed Bratianu, who was very upset over the bad news from various sites on the front, but who focused his ire on Sarrail for his failure to draw off any divisions from von Mackensen’s army operating in the Dobrogea.42 In fact, despite the dismal military situation, Bratianu intervened only once on his own in military matters: when Turtucaia fell, and he demanded more security for the capital. However, he insisted on knowing the contents of the daily communiqué ahead of everyone else. The queen likewise never openly intervened, but she liked to know what was going on, and she often came by the operations section and insisted on being given detailed information.43

Berthelot next approached Joffre, asking him to intercede with the tsar for reinforcements for the Dobrogea and Moldavia so the Romanian army of the north could take a breather. From the 23rd on, Berthelot participated in the monarch’s daily operations briefings at 11:30 PM, and, as he wrote his sister, began to act as a shadow chief of staff.44

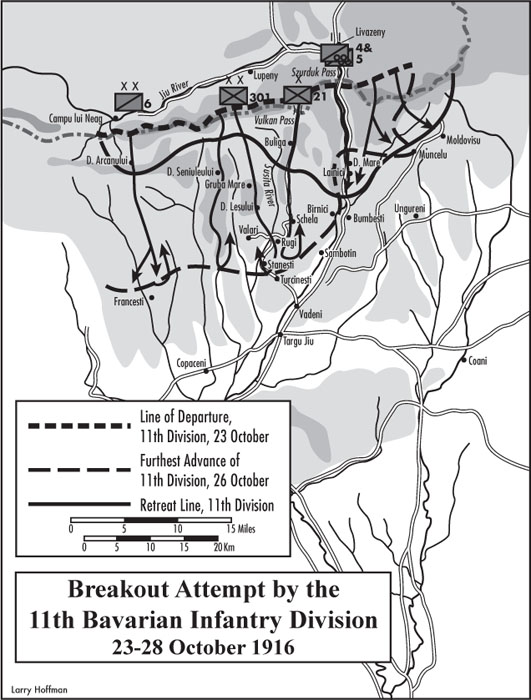

While Austro-German forces kept the Romanians engaged at the Oitoz, Brasov, and Red Tower Pass regions, von Falkenhayn decided to force the Vulkan and Szurduk Passes with the 11th Bavarian Division, coming from the Stochod region in Russia. The railroads ran to Livadia, but the 9th Army, concerned about keeping the operation secret, elected to have the unit unload at Deva, twenty-five miles farther north.45 Von Falkenhayn told Major Wilhelm von Leeb (1876–1956), the division’s general staff officer, that the unit would be spearheading an assault over the Vulkan Pass. The 11th Bavarian Division, known as the “Flying Division” because it had participated in all the major campaigns of the war, had taken severe losses at Verdun in the first half of 1916. In mid-July, the division had 5,400 soldiers instead of its usual 9,000. It is not known how many of the losses had been made good by the time the unit moved to Romania.46

The 11th began to arrive on 14 October. Its commander, Major General Paul Ritter von Kneussl (1862–1928), arrived at Deva at 2 AM on the 15th, where a warning order from the 9th Army awaited him. Von Falkenhayn had outlined the impending attack in the Jiu Valley, telling the Bavarian general what additional forces he had besides his own division. Von Kneussl was to stage a breakout over the mountains through either of the Vulkan-Szurduk Passes, creating an opening in the Romanian defense lines that would permit the 6th and 7th Cavalry Divisions to cross the mountains and swing east, pushing the enemy from Walachia.47 Von Falkenhayn wanted to know von Kneussl’s plans as soon as possible.48 The Bavarian general and his chief, von Leeb, brought up to date on the region by von Busse, whose 301st Division headquarters had remained in Petrosani, pored over the maps. They concluded that a frontal assault down the Szurduk Pass by itself had scant chance of success, and the terrain to its east ruled out an advance there. Von Kneussl told the 9th Army that his units would advance in two columns: one marching over the Vulkan Pass and a second advancing between the Vulkan and Szurduk Passes. The division would not complete its arrival until the 18th, so von Kneusel set the date of the start of the crossing for the early morning hours of 23 October.49

Despite the lateness of the season and the difficulty in keeping the operation a secret from the enemy, the risk was acceptable to von Falkenhayn. Von Kneussl modified his plan after he saw the terrain. He added a third column under von Busse, whose mission was to draw off enemy forces by taking Arcanului Mountain on the far western flank, then pushing east toward the Vulkan Pass. The division’s 21st Brigade formed the center column and was responsible for forcing both passes. The regiments of the 21st Brigade with artillery were to cross the Vulkan Pass, while the two bicycle battalions had the task of sweeping the Szurduk Pass. A third column, led by Austrian Colonel Stavinsky and largely consisting of the 144th Austrian Infantry Brigade, had orders to advance along the crest and east side of the Szurduk Pass.50 Von Kneussl informed the 9th Army that although the mission was tactically difficult, his unit could accomplish it in light of the estimated enemy opposition – six regiments. He added a cautionary note: “Heavy snowfall could make this plan unworkable.”51

Unfortunately for von Kneussl, his operation was jeopardized when von Falkenhayn diverted one of the division’s three regiments, Reserve Infantry Regiment 13, to reinforce the Alpine Corps, leaving only two infantry regiments, the cyclists, and the Austrian brigade. Although von Kneussl shared von Falkenhayn’s view that the Austrian infantry (the coal miners) were not suitable for an offensive operation, the paucity of infantry troubled him.52 The weakness of the infantry force in the Jiu region also bothered Archduke Karl, who told Conrad that in spite of this problem, a coup de main was their best hope for breaking through the mountains until further German reinforcements arrived.53 Von Kneussl thought about dismounting some of the cavalry regiments in order to assist the infantry, but he rejected that idea in light of the purpose of the assault, which was to conduct a breakthrough so the cavalry could cross the mountains and fan out in Walachia. Von Falkenhayn had made it clear that the cavalry was not to get bogged down in clearing the passes.54 With that restriction, the best von Kneussl could do was to shuffle his units around a bit and have the cavalry cross the mountains behind von Busse’s diversionary thrust to the west of the passes. Von Kneussl had ruled out the Vulkan Pass road for the cavalry because his own division’s artillery and combat trains would be using it, and the traffic would likely block the pass for some time. Von Busse’s line of advance offered the shortest and fastest route into Walachia. Few enemy were expected to be in the area. Once across the border at the mountain crest, there were new Romanian roads leading to Francesti. The major disadvantage to crossing the trackless mountain region was that it involved enormous difficulties in moving the supply wagons and artillery. On the evening of the 21st, a 6th Cavalry Division operations officer reported the results of his reconnaissance to von Kneussl. “Difficult,” he said, “but feasible within the time we have.” The officer also stated that 250 pairs of oxen and several winches would greatly facilitate matters, and that some engineering work was needed in a few spots on the climb to Arcanului.55

Ideally, von Falkenhayn wanted all his units to begin their attacks on the same day, to prevent the Romanians from shifting forces from one region to another. That did not happen because it took time for von Kneussl to organize his division after its arrival from Russia. The Alpine Corps began its advance on the 16th, while von Morgen had continued his drive against the Romanians defending Campulung following his capture of Rucar on the 14th.56 Despite von Staabs’s lack of enthusiasm, his forces resumed the offensive and captured the Tömöser Pass on the 24th.57 The only unit that failed to advance was the Orsova force under Hungarian Colonel Alexander Ritter Szivo de Bunya (1868–1945).

Even Archduke Karl had given up the idea of crossing the mountains south of Brasov or east into Moldavia. Anticipating a Russian offensive near the juncture of the 1st and 7th Armies, the AOK had directed the movement of the 8th Bavarian Reserve Division from the Oitoz Pass to the area near the Tulghes Pass, effectively shutting down any hopes for crossing the mountains near Ocna. Karl told Conrad that under these circumstances, “our only hope is to exploit the successes from Transylvania and the offensive of 11th Bavarian Division at Hateg.” And Karl was not sanguine about the effort in the Jiu Valley, expressing fear that one division did not have the strength to do the job.58

Meanwhile, the Romanians had adjusted their defenses. After the reverses at Sibiu and in the passes south of Brasov, the Romanian general headquarters decided to restructure its defenses. Up to mid-October, the Romanian forces had generally tried to defend each mountain pass throughout its length, and the Germans had twice outflanked the Romanians: at the Red Tower Pass in September and at Rucar in the Bran Pass in October. The general headquarters now decided to block the exit of each pass with a medium-size force, usually a brigade, instead of a division, holding the remainder in reserve for a counterattack. Most of the reserve brigades of the 1st and 11th Divisions were moved south to Filiasi, in the Jiu Valley, where they could rapidly be moved to block any enemy penetration emanating from either Orsova or Petrosani. The remaining battalions went to Pitesti, where they were merged into a reconstituted division, the 2nd, forming part of the reserve force that Berthelot had formed.59

Having exerted pressure all along the Transylvanian Front now paid off for von Falkenhayn. In response to von Morgen’s I Corps advance in the Bran Pass area, Averescu had called for reinforcements, which the Romanian headquarters took from the 1st Army, ordering Culcer to send six battalions and some artillery from his area to Campulung. Although Culcer reluctantly complied, he did not take the units equally from both the Jiu and Olt regions, as Iliescu had suggested. Instead, he took all six from the 11th Division reserve in the Jiu Valley. This left him with only three detachments, each with three battalions, at the exits of the Vulkan and Szurduk Passes. All of these units came under the command of Colonel Ioan Anastasiu, commander of the 22nd Brigade.60

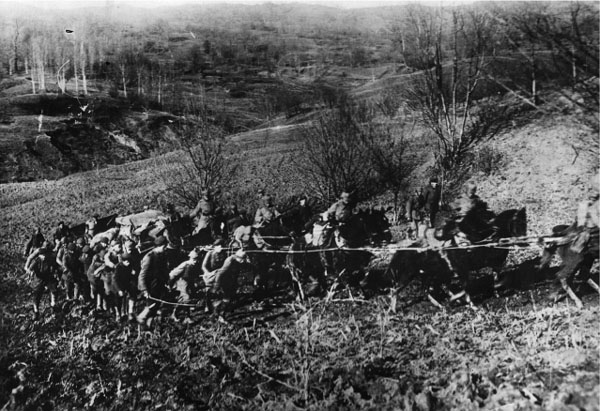

Von Kneussl knew of Krafft’s progress to his east, which was tying up the Romanian I Army Corps. To keep the energetic General Dragalina – whose 1st Division besieged the Austrians at Orsova – similarly occupied, von Kneussl asked Szivo to launch an attack.61 Szivo did not, but the Bavarians began their advance over the mountains on the 23rd as planned.62 The Germans were to have started at first light,63 in an effort to gain surprise, but thick fog, which rendered the artillery useless, delayed the operation until 11:30 AM in some places. The fog persisted, slowing the advance. The cyclists, heading down the Szurduk Pass, made the least progress. The narrow defile with its vertical walls ruled out any type of attack except a frontal assault, for which the Germans had neither the manpower nor the will. The column came to a halt soon after crossing the Romanian border. Colonel Schulz’s 21st Brigade in the center (in the Vulkan Pass) had a hard time as well, the terrain being the greatest obstacle. The road over the pass was little more than a path, presenting enormous difficulties to the movement of men and materiel. To get the artillery over the crest of the Vulkan Pass required teams of oxen assisted by scores of soldiers manning massive winches, making it clear that this route was not suitable for any manner of sustained logistical support.

When the German and Austrian battalions appeared in the morning mist and fog, Anastasiu advised his superiors that he needed at least five battalions of infantry reinforcements immediately. The staff at 1st Army sent the request to the Romanian headquarters, and later that night Culcer sent a gloomy assessment to the king, advising him that the 1st Army was being attacked along its entire front – from the Cerna Valley north of Orsova to the Olt River. He reported that his forces would have to retreat on the Jiu Front because of the enemy’s superiority. He stated that his 11th Division had only sixteen battalions to defend a front twenty miles long. He also indicated that his ammunition stockpiles were almost exhausted.64 In response, the king told Culcer the next day that there could be no retreat, but Culcer had already lost control of the situation and requested that his forces be allowed to pull back in some locations. This action horrified Berthelot, who called for Culcer’s relief. Ferdinand agreed, appointing the aggressive Dragalina as commander on the 24th.65 Tragically, Dragalina was mortally wounded the next day while conducting a reconnaissance in the Szurduk Pass. The High Command named General Nicholae Petala, I Corps commander, to succeed him.66

Farther west, von Busse’s team of Germans and Austrians had made the greatest gains. One of his two groups made steady progress, reaching Dobrita by the 25th. His eastern column passed over the Grube Mare massif and through Lesului to Stanesti. At this point, von Kneussl decided that he had to open the Szurduk Pass. He had Schulz’s 21st Brigade attack from the west, while von Busse’s group received orders to attack from the southwest, toward Sambotin and Bumbesti. He kept prodding the two cyclist battalions inside the Szurduk Pass to move faster.67

At the same time, the 6th Cavalry Division had moved from Petrosani along the Jiu rominesc to Campu lui Neag, where the horses and riders turned into the mountains toward Arcanului Mountain and began climbing into the clouds. Von Kneussl’s greatest worry now was the possibility of enemy reinforcements coming from Orsova, so he requested aerial reconnaissance.68 His fears proved justified. Petala had begun the shuffling of troops from the I Corps in the Olt region to the Jiu Valley. Szivo’s forces at Orsova had not engaged the enemy as ordered, and Dragalina, before he was wounded, had taken advantage of the Austrian inaction to order battalions from his former division, the 1st, to the Jiu Valley. The movement of troops from the Red Tower Pass and Orsova gave the Romanian 1st Army a local superiority against the Central Powers in the Jiu Valley, and Petala planned to strike.69

That evening von Falkenhayn at the 9th Army called to see how the operation had developed and inquired about the possibility of sending the 7th Cavalry Division behind the 6th. Von Kneussl explained that the Vulkan Pass had proven unsuitable for transporting supplies, necessitating a change in plans. He had to redirect his units to the Szurduk Pass, adding that without heavy artillery, clearing it of the enemy would be a slow and laborious process. As for deploying the 7th Cavalry, von Kneussl felt that was not warranted until the Szurduk Pass was open. The road over the Vulkan Mountains could not carry the traffic necessary for supplying the cavalry. The staff at the 9th Army agreed, but reiterated that the main purpose of the operation was to get the cavalry into Walachia as rapidly as possible. Once the cavalry divisions were over the mountains, they could envelop the enemy and open the passes. Von Falkenhayn stressed that at this time, opening the Szurduk Pass to gain a supply route was not essential; the cavalry could live off the countryside. Getting the cavalry over the mountains was the mission.70

On the 26th, the weather was cold but clear. The 3rd Cavalry Brigade had reached the outskirts of Francesti, while the 8th had started to enter the mountains at Arcanului. The 5th Brigade waited its turn in Campu lui Neag. Burdened by too much baggage, the cavalry staggered over the mountains at what seemed a lackadaisical pace to von Kneussl, and in the afternoon he urged them to speed things up. Francesti was the last obstacle, and they needed to get there as soon as possible. He pointed out that the entire operation was aimed at securing them a fast passage, and if his own infantry could leave their field kitchens behind and subsist on iron rations – the equivalent of today’s “meal’s ready to eat,” he expected the same from the cavalry.71

During the night of 26–27 October, the weather took a severe turn for the worse. At lower altitudes, a dense fog covered everything. Rain streamed down, erasing the forest paths used by the infantry and cavalry. Supply columns got lost and wandered in circles. At higher altitudes, the temperature plummeted, and over three feet of snow fell. The pack animals carrying supplies over the crest of the mountains could not get through the deep snow and collapsed from exhaustion. At 10 AM, large numbers of Romanians attacked von Busse’s column from the south and east, along a line from the villages of Sambotin and Birnici. In the afternoon, further strong enemy attacks began against the Bavarians along the southern edge, near Dobrita and Stanesti. Romanian prisoners revealed that their regiment had come from Turnu Severin and had the mission of driving the Germans back to Petrosani. Petala had promised a prize of 1,000 lei and a decoration to anyone capturing an enemy artillery piece.72 The extra incentive, about the equivalent of a year’s pay for a worker, paid off. The Romanians broke through the German lines in several places, capturing two guns and driving the infantry back into the mountains. The 5th Cyclist Battalion remained in control of most of the Szurduk Pass after von Falkenhayn directed that it be held at all costs. To the west, the Romanians drove the German 6th Cavalry Division scurrying back into the foothills around 2 PM. Overturned equipment in the mountains blocked the pathway, and the German cavalry could not mass troops for a counterattack.73

The accidents that occurred during the crossing of the mountains, along with the heavy snow, severed the supply lines, and by the next day (the 28th), shortages had reached the crisis stage everywhere: there was no food, fodder, or ammunition. It took several days to get the bulk of the units back to safety, or at least to a location where food could reach them. The exhausted animals could barely move in the snow. After several of them collapsed, 6th Cavalry Division commander, General Georg Saenger (1858–1934), ordered his men to retreat. They abandoned five cannons after spiking them, and another three slipped over cliffs. The cavalry returned to Arcanuli on the 31st.74 The 4th Cyclist Battalion, which had gone along the east side of the crest above the Szurduk Pass, was lost for two days in snowstorms, stumbling back on the 30th in such poor shape that it had to be sent to Petrosani for recuperation and reconstitution. The one company from the Württemberg Mountain Battalion that participated in the operation had a hard time. Their clothes froze to their bodies. Water to cool their machine guns also froze.75

Von Falkenhayn’s headquarters staff recognized immediately that the Romanian counterattack marked the end of von Kneussl’s operation, and von Falkenhayn told him to hold on to his lines of communication in the Szurduk Pass at all costs; other losses could be recovered later. With the enemy penetrating between the understrength and isolated Austrian and German columns, they could not assist each other, much less force open a gap for the cavalry. For a week after the Romanian counterattack, stragglers wandered back to the German lines. Shaken returnees talked about the wild fury of the Romanians, along with the privations they had endured while they were lost.76 The losses were steep. The Central Powers reported casualties of 53 officers and 3,157 soldiers.77 On the south side of the Carpathians, Petala told King Ferdinand, “in general, the situation of the 1st Army is much improved on account of the action undertaken near Targu Jiu” on the 27th.78

Von Falkenhayn had no regrets about the failure of von Kneussl’s shoestring operation, but at higher headquarters the setback to the 11th Bavarian Division reopened the question of which location offered the best prospects of a breakthrough into Romania. The OHL had found two more divisions for Transylvania, the 41st and the 109th. Ludendorff, Conrad, and Archduke Karl all thought that with the extra manpower, the main effort could be switched to the area south of Brasov. Von Falkenhayn admitted that one could make a case for that area, but he was adamant that with winter coming on, the Szurduk Pass remained the best approach. In addition to his previous rationale, focused on the railway situation and the length of the pass, he now cited the fact that von Kneussl’s men had established that there were roads on either side of the passes that permitted the movement of infantry. He also insisted that the Bavarian probe had provided a good estimate of the enemy strength. The Germans, he pointed out, still held the pass all the way to its south exit, and they also held the crest of the Vulkan Pass. The Romanians’ success in rolling back von Kneussl’s division would lead them to believe the Central Powers would abandon their plan to breakthrough in this area.79 If the Germans tried again in the same area, surprise would be on their side. Bolstering his argument was the fact that the progress of his forces elsewhere offered little hope for any immediate success: the Alpine Corps had advanced farther south than either the I or XXXIX Reserve Corps, but even Krafft was making dismally slow headway, and he had a long way to go before reaching the Walachian plain. As for von Schmettow’s corps in the Oitoz Pass, von Falkenhayn had always regarded it as an eccentric approach that only complicated logistical issues.80

The archduke and his headquarters held the opposite view, favoring action in the Oitoz Pass. Unfortunately, despite the energetic efforts of von Schmettow and Goldbach, operations there had stalled. Von Falkenhayn advised Archduke Karl that if he wanted von Schmettow and Goldbach to break into the Ocna Valley on the Moldavian side of the Carpathians, they needed an additional infantry division fully outfitted and trained for mountain warfare.81 Neither the Germans nor the Austrians could provide such a unit. On 22 October, the archduke’s headquarters informed von Falkenhayn that he would be getting the 8th Bavarian Reserve Division, along with the LIV General Command (Special Purpose), led by Major General Viktor Kühne (1857–1945). The Bavarian division had no special winter warfare training. The archduke planned to send the Bavarians and Kühne’s headquarters to join the Austrian 71st Infantry and 1st Cavalry Divisions. Von Falkenhayn welcomed the arrival of the LIV Corps. He did not think it was needed in the Oitoz region, but he did not complain, because it allowed him to shift von Schmettow and his staff to the Szurduk region, where he used them as a cavalry corps headquarters, controlling the 6th and 7th Cavalry Divisions.82

When von Schmettow arrived at Petrosani, he found his cavalry commanders, Saenger (6th) and Albert von Mutius (1862–1937; 7th), in an uproar. Von Falkenhayn’s latest directives envisioned the cavalry crossing over the mountains between Arcanuli and the Vulkan Pass and then living off the land in Walachia. The two generals balked when they saw those orders; they did not want to go back over the same route that had already cost them six artillery pieces, and they talked von Schmettow into going to Brasov to persuade von Falkenhayn to change his mind.83 It did not take much effort, for the 9th Army commander had meanwhile persuaded the OHL of the validity of his arguments for resuming the breakthrough in the area of the Vulkan and Szurduk Passes, and he had convinced Ludendorff to send both of the newly available divisions to Hateg. The addition of these two divisions gave the 9th Army adequate infantry to force the Szurduk Pass.84 Ludendorff’s tepid support for the venture nonetheless led him to overrule Archduke Karl, whose headquarters now wanted to send one of the divisions to Sibiu and the other to Brasov.85 Having lost that battle, Karl realized he did not need a corps headquarters in the Oitoz Pass region, and he released Kühne and his staff to von Falkenhayn on the 29th. The latter immediately moved the LIV Corps to Petrosani and assigned Kühne responsibility for breaching the Szurduk Pass, while von Schmettow was to exploit the situation in the enemy’s rear following the breakout. Arz’s 1st Army took over the Oitoz Pass region, allowing the 9th Army to concentrate on the mountain crossing and exploitation. Arz placed General Hermann Freiherr von Stein (1859–1928), commander of the newly arrived 8th Bavarian Division, in charge of the forces in the pass.86

Kühne arrived in Petrosani on the 29th and took over the forces in the area two days later. Von Falkenhayn gave him the two infantry divisions that the OHL had just sent to Transylvania, the 41st and 109th. He told Kühne his job was to open the way through the mountains for von Schmettow’s cavalry corps to move onto the Romanian plain. Kühne was then to turn his corps to the southeast along the foot of the Transylvanian Alps. Von Schmettow’s cavalry would provide a screen south of the LIV Corps. Both corps would move east toward Bucharest, being joined by the remaining German forces (under Krafft, von Morgen, and von Staabs) emerging from the mountains and by von Mackensen’s army coming from the south, pushing the Romanians from Walachia. The operation was to start on 5 November.87

Von Falkenhayn notified his other corps commanders about the breakout, ascertaining to what extent they could launch offensives to keep the Romanians’ hands tied. Von Morgen argued that without a fresh division, he could not break into the Campulung Basin. Von Staabs echoed von Morgen, saying that he too could use some help, while the 89th Division commander, von Lüttwitz, added that he needed at least three weeks before he could launch an offensive. Von Falkenhayn gave von Morgen some squadrons from the 3rd Cavalry Division and ordered him to push on, engaging as many of the enemy as possible. The 9th Army got some extra assistance the next day, when Archduke Karl’s headquarters agreed to let it have the 2nd Bicycle Brigade for a thrust at Orsova. And much to von Falkenhayn’s surprise, Ludendorff told him he had found an extra infantry division, the 216th, which would start arriving on 4 November. Von Falkenhayn decided to send it to the Krafft Group. The more Romanians that were tied up in the Red Tower Pass, the fewer would be available to assist their comrades to the west in the Jiu Valley once Kühne began his operation.88

On 1 November, von Falkenhayn arrived in Petrosani to meet with Kühne, von Kneussl, von Schmettow, and von Busse. He made a personal reconnaissance of the Szurduk Pass region, which led him to move the starting day back to the 7th, and finally to the 11th. Preparing the roads for heavy traffic, especially in the Vulkan Pass, and fixing bridges caused the delay. The slope at the Vulkan Pass varied from 15 to 25 percent in places, and it took a team of twelve horses to move each artillery piece and supply wagon up and over the crest. Ice and snow worsened matters. Field cable cars and other devices were hastily constructed, including winch stations to assist the teams of animals and men. In addition, von Falkenhayn discovered that the 6th Cavalry Division was in no shape for immediate action after its harrowing retreat back over the Vulkan Mountains. As von Schmettow’s operations officer pointed out, “almost every third man was shod on one leg with a riding boot and on the other with a laced shoe.” Finally, von Falkenhayn sat down with everyone and spelled out his concept of how things should unfold, telling Kühne to advance both in and alongside the passes with mountain units, if possible, at the head of each of his columns during the attack.89

In fact, the 9th Army had just assigned the Württemberg Mountain Battalion to the LIV Corps. Formed in late 1915, the Württemberg battalion was the only unit in the German army other than Krafft’s Alpine Corps that was equipped and trained for combat in mountain terrain. The battalion had arrived at the end of October from the Vosges Mountains in Alsace with a strength of 1,800 men, and one of its companies had immediately ascended the heights to relieve one of von Kneussl’s shattered units. The initial destination was the market square in Petrosani. It was only fifteen miles distant, noted one officer,

but the enemy had destroyed the bridges. It took us 18 hours, and every soldier will long remember it. The road was loose mud, and the few bridges were gone. The wagons and cars could not make it. Every now and then we came across a dead horse blocking the road. Enemy wagons lay on the side of the road…. When we got there, at 3:45 AM, we had been at it [all day] … with full pack[s], and we jumped into whatever quarters we could find.90

The next day saw the Württembergers heading into the Vulkan Mountains, east of the pass. That night they began patrols into Romania, probing the enemy defenses.

In Petrosani, after talking with von Kneussl, von Schmettow, and von Busse, Kühne knew he could not use the Vulkan Pass. The roads there and in the mountains were too steep and inadequate for the heavy artillery and the logistical support required for a force of four infantry and two cavalry divisions. Only the highway in the Szurduk Pass had the capacity for moving his artillery and supplies, and although von Kneussl’s troops held the pass, the Romanians sat in excellent entrenchments opposite its exit to the south, blocking egress. Worse, the Szurduk Pass highway itself was something of an Achilles’ heel. In the defile on one side of the road, cliffs rose vertically for hundreds of feet, and on the other side the Jiu River raced southward in a mad and uncontrollable torrent. The road generally consisted of a single lane. In only one or two places along the twenty-mile length of the defile were there areas wide enough to establish vital ammunition dumps, horse and mule remount stations, control points, and the like.91

Over the next two to three days, the LIV Corps moved its heavy artillery to the exit of the pass in the south and emplaced the guns where they could be used to pummel the Romanians during the breakout. Some of the leading infantry would advance along the paths and small roads along the heights above the defile, and more units were assigned to march down the pass. A few of the battalions of General Heinrich Schmidt von Knobelsdorf’s (1859–1943) 41st Division would go along the crest of the west side of the pass, while the rest of the division would march in the pass. To the west of the 41st Division was the Württemberg Mountain Battalion. The 109th Division, led by General Horst Edler von Oetinger (1857–1928), would march along the ridge above the east side of the pass. Behind the 41st Division came the Bavarian 11th, although several of its battalions had orders to cross the Vulkan Pass in a feint to throw off the Romanians. Von Busse’s 301st Division was marching behind the 109th Division. When the infantry had broken through, von Schmettow’s cavalry would follow and enter Walachia.92 The density of the traffic demanded thorough regulation. March tables accounted for every minute of every hour, to accomplish the staging and movement of all the artillery and unit equipment. Regulation points manned by officers and military police abounded. Standing orders called for any vehicle that broke down to be pushed immediately into the Jiu River.93

Von Falkenhayn kept the 9th Army headquarters in Brasov as part of a deception plan to keep the Romanians unaware of the impending offensive to the west. He made sure his presence in Brasov received lots of attention. He conducted inspections, had parades and reviews with the two corps to the south, visited hospitals, awarded decorations and promotions, and had highly visible meetings with local officials.94

He also quarreled ceaselessly with higher headquarters. Archduke Karl and von Seeckt had not entirely given up the notion of driving south from Brasov. Karl brought the idea up again when there were some logistical issues connected with supplying the two newly arrived infantry divisions, the 41st and the 109th.95 Von Falkenhayn fought with the Army Front headquarters over the assignment of both the Bavarian 8th Reserve and 10th Divisions. He wanted them for the breakout; von Seeckt wanted them to shore up Arz’s faltering 1st Army, which faced a large Russian build-up. Von Seeckt won that fight. Angrily, von Falkenhayn protested to the OHL on 30 October, but to no avail.96

Disputes arose over petty things, mainly from the archduke’s insistence that the 9th Army get under way immediately. Von Falkenhayn demurred, owing to the necessity of conducting road and bridge improvements.97 Von Seeckt and Archduke Karl contended that von Falkenhayn had gotten lost in details and was unreasonable, and his practice of communicating directly with the OHL set off both leaders at the Army Front. As von Seeckt had once told his wife, “Falkenhayn is not an easily handled subordinate” and “I would not want to be the chief [of staff] under Falkenhayn.”98

The crowning touch came when the 9th Army commander advised the archduke’s headquarters on 3 November that the Szurduk Pass attack could not come until the 7th at the earliest. Von Seeckt responded by demanding reports on every step taken to date, which von Falkenhayn described as “a really unbelievable directive from Archduke Karl that demands undignified and irrational things from me.” Von Falkenhayn’s angry retort forced Karl to visit the LIV Corps headquarters the next day to put out the fire – without von Seeckt accompanying him.99 Von Falkenhayn lost his temper over the myriad reports the archduke’s headquarters had demanded, and he was overheard shouting, “What is your Imperial Highness thinking about? Who do you think is in front of you? I am an experienced Prussian general!” The archduke refused to back down and replied: “The order still stands.”100 The archduke discovered that the breakout offensive was now scheduled to start on the 11th at earliest. Von Falkenhayn’s generals justified their decision to postpone things because of the poor quality of the roads, an assessment with which the archduke agreed. He had noted as he arrived that the road from Hateg to Petrosani was clogged with trucks and unit combat trains. Kühne then outlined his plan of attack. The archduke noted that he thought that the weak point was the massing of artillery near the exit from the Szurduk Pass, which was so narrow that most of the guns could not be brought to bear on the enemy. Kühne, an artilleryman, explained that he had no choice. His soldiers could not drag the heavy guns up to the heights on the crest of the pass. Were he trying the breakout against the French, Kühne thought it would not work, but he had confidence that the inexperienced Romanians would wilt in the fire from the few guns he could bring to bear. Karl grudgingly agreed, but later that day he told Conrad that he feared that once the force was out of the hills, it would not have the strength to resist Romanian counterattacks. They needed von Mackensen to save the day, he wrote.101

Archduke Karl and von Falkenhayn were not the only high-ranking visitors in the region. Twenty-five miles to the south, on the 9th, Berthelot looked north from Bumbesti at the exit of the Vulkan Pass. He was making a staff visit, probably responding to a report by the 1st Army a few days earlier, in which the army staff stated that the Austro-German forces were trying to enter Romania through the Jiu or Olt Valleys. The report was not alarming and indicated that morale was better in the Jiu region, but it warned that should the full weight of the enemy’s 41st Division be committed, additional help would be necessary.102 Accompanying Berthelot were General Paraschiv Vasilescu, 1st Army commander; Anastasiu, 11th Division acting commander; and Lieutenant Colonel Mihail Obogeanu, commander of the 41st Infantry Regiment.103 The soldiers of the 41st had repulsed von Kneussl’s Bavarians ten days earlier, but to Berthelot, Obogeanu’s four battalions seemed inadequate. Vasilescu could not have been of much help; he was seeing the battlefield for the first time himself. Formerly the I Corps commander in the Olt Valley region, where he had relieved the mortally wounded General David Praporgescu on 13 October, he had just taken command of the 1st Army from Petala, who had run himself into the ground. When his French liaison officer, Major Theodore Caput (1873–1961), told Petala he appeared tired, he promptly requested sick leave.104 Vasilescu became the fourth general to command the 1st Army in less than two weeks.

Unfortunately, Berthelot’s concerns about the situation at the Vulkan Pass got lost because of the 9th Army’s divisionary attacks and his animosity toward Averescu. On returning to Peris, Berthelot found that the Romanian staff had its hands full responding to ferocious combat all along the line of the Alps, from the Red Tower Pass to Buzau. Krafft’s Group threatened Poiana Spinuli and Mount Cozia. Hard fighting raged south of Brasov, both near Campulung and at the Predeal Pass, where the worn-out 10th Division had to be relieved by the 21st Division. The process was just beginning.105 Averescu’s continuous pleas for additional units disgusted his French counterpart, who let his animosity toward the Romanian general divert his focus from the crisis emerging on the northwest frontier. “He’s insatiable,” spewed Berthelot. “Narrow-minded, thin-skinned, undisciplined, the epitome of a political general.” Later that night in Bucharest, he told the prime minister that “the man is a danger to Romania.” Bratianu admitted to sharing the same opinion.106

At the opposite end of the country – in Moldavia, where Prezan’s 4th Army and the Russian 9th Army joined – there were some signs that the long promised and hoped-for Russian attack, which would certainly relieve some of the pressure building on the Romanian units holding in the southern passes, might actually take place.107 Nonetheless, Berthelot, not thinking that the Germans would repeat an advance where they had just suffered a repulse, focused on building a substantial reserve to handle the inevitable Central Powers’ assault from Transylvania,108 and – not a little blinded by his dislike of Averescu – momentarily lost sight of the storm building to the northwest.

On the 10th, von Falkenhayn gave the order for a general attack to commence the next morning along the entire front of the southern Transylvanian Alps, from Orsova to Buzau.109 The infantry divisions started moving into the Szurduk Pass on the 10th. Von Schmettow’s two cavalry divisions remained behind in Petrosani, waiting for the signal to move out. Infantry columns, artillery, caissons, supply wagons, and field medical units began moving. The staging resembled the mariner’s old adage about “a place for everything and everything in its place.” With almost four divisions, every square inch of space in the Szurduk Pass was accounted for, and woe to the officer or noncommissioned officer whose men or equipment went to the wrong destination. East and west of the passes, the fighting had already started. In the west, the Württembergers had left their camp on the border, near Prislop, had taken the Grube Mare massif, and stood ready to move south.110 The 22d Bavarian Infantry Regiment (11th Bavarian Division) had ascended the Vulkan Pass and halted in Buliga, poised to advance on the 11th.111 On the east side of the Szurduk Pass, an Austro-German task force under Colonel Eduard Stavinksy had overrun Muncelul.

On the night of the 10th, the sky was clear and a moon appeared, but there was a dense fog in the valley. For the troops on the heights staring down into the ravines and basins, it seemed as if they were gazing at the surface of a lake, with the moonlight reflecting off the thick fog, giving every valley and ravine the appearance of a body of water. At the top of the Szurduk Pass, the divisions had moved into place and lined up: Schmidt von Knobelsdorf’s 41st Division, von Busse’s 301st, and von Kneussl’s 11th Bavarians. Von Oetinger’s 109th was already at the end of the pass. Sixty thousand men with some thirty thousand horses had jockeyed into place. The advance would begin at 5 AM the next day with the 109th stepping off, followed by the 41st at 8 AM, the 301st at 10 AM and the Bavarians at noon. The artillery was to open fire as soon as it could identify targets.112 Von Falkenhayn had notified Kühne that he would be there early to watch the start of the operation. The stakes were immense. If the assault did not succeed, there would probably not be time for another before freezing weather shut down operations, leaving the Central Powers manning an extra 750 miles of front in the most remote and backward corner of their hinterland. Von Falkenhayn’s future also rested on the outcome. His superiors had wanted him to advance from the Brasov region, but he had insisted on the Jiu Valley, twice overcoming their objections and advice. He was calm; those around him were not. The first breakthrough attempt had not succeeded; a second failure would not be tolerated. The hushed tones and whispers from his subordinates about a “second Verdun” never seemed to reach him.113

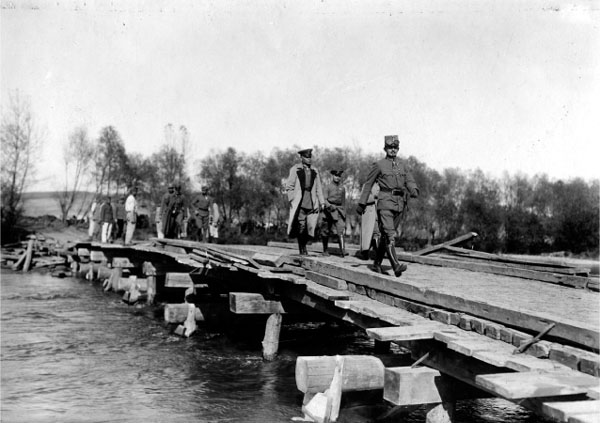

Archduke Karl, General Erich von Falkenhayn, and Colonel Hans Hesse. The archduke (with goggles) is next to the car, talking to von Falkenhayn; Hesse is behind them, with his hands on his sword. (ÖStA, Ru. 07–1737)

General Hermann von Staabs (BArch, 146–2012-0036)

General Viktor Kühne (BArch, 183–2012-0416–500)

General Count Eberhard von Schmettow (BArch, 146–2012-0037)

General Konrad Krafft von Dellmensingen (BArch, 183-R11612)

Major General Kurt von Morgen reviewing troops in snowstorm at Focsani (ÖStA, Ru. 08–2375)

(Facing) General Gerhard Tappen (center) and Field Marshal August von Mackensen (right, with field marshal’s baton in his right hand) observing Austrian Pioneer Troops assembling the bridge crossing the Danube at Sistov. (BKA, Stg. 9352)

Lieutenant General Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf in foreground at the map table. The identity of the officer in the background is not known. (BArch, 183-R32730)

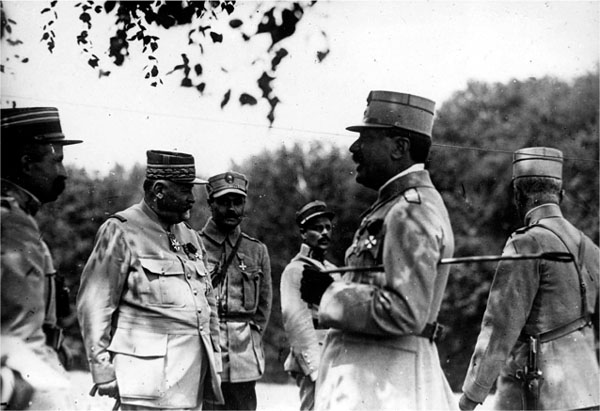

Austrian 1st Army commander Lieutenant General Artur Arz Strauss von Straussenburg (in staff car facing photographer) and General Anton Goldbach, commander of the 71st Austrian Infantry Troop Division (standing next to the car) (ÖStA, Ru. 06–1049)

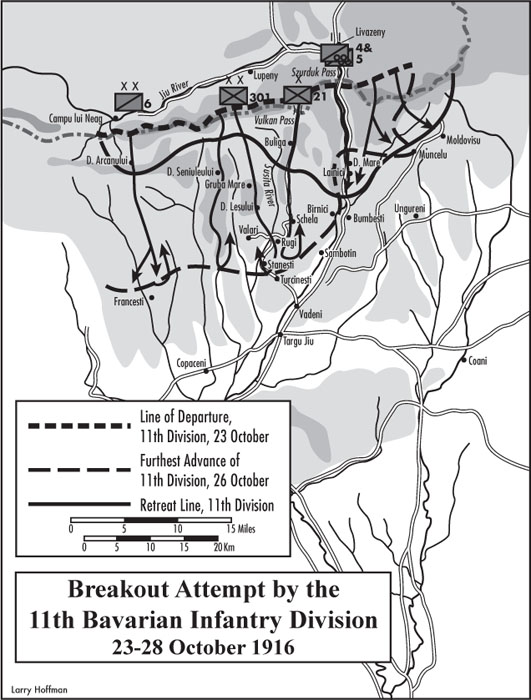

(Facing) Archduke Karl and his chief of staff, General Hans von Seeckt, crossing the Olt River. Karl leads the way and von Seeckt, in an open overcoat, follows. (ÖStA, Ru. 07–1732)

Archduke Karl (left, in overcoat) and General Kühne (center, hand on sword) at Petrosani. General Paul Ritter von Kneussl of the 11th Bavarian Division stands at the entrance to the building, holding a map. (ÖStA, Ru. 07–1770)

King Ferdinand (seated) with Generals Alexandru Averescu (leaning over the king) and Artur Vaitoianu (with his hands behind his back) (RNMM, 1734E)

Major General Henri-Mathias Berthelot, chief of the French Military Mission (RNMM, 2701E)

General Constantin Prezan (RNMM, 35971)

General Alexandru Averescu (RNMM, 36503)

General Vasile Zottu (RNMM, 1300 7568)

Brigadier General Dumitru Iliescu (Herbert Wrigley Wilson and John Alexander Hammerton, The Great War: The Standard History of the All-Europe Conflict [London: Amalgated, 1917], 7:519)

General Milhail Aslan (RNMM, 1300 7596)

General Ion Culcer (getting into staff car) (RNMM, 60640)

General Ion Popovici (RNMM, 19598)

General Grighore Crainiceanu (RNMM, 1300 6840)

Queen Marie and General Berthelot at a hospital (RNMM, 2692E)

(Facing) Generals Eremia Grigorescu (with the riding crop) and Berthelot (RNMM, 3099E)

German soldiers struggling on impassable roads (BKA, Stg. 9143)

German Artillery bogged down (BKA, Stg. 9128)

(Facing) Moving a German artillery piece to a hilltop (BArch, 183–529505)

The Red Tower, Red Tower Pass (BKA, Stg. 9440)

The Szurduk Pass (BKA, Stg. 15460)

Austrian armored train (ÖStA, Ru. 06–1083)

Austrian 305mm mortar (“Skinny Emma”) in action (Imperial War Museum, London, Q023947)

Romanian artillery in action (Romanian National Library, Bucharest)

Mobilized Romanian artillery battery (Romanian National Library, Bucharest)