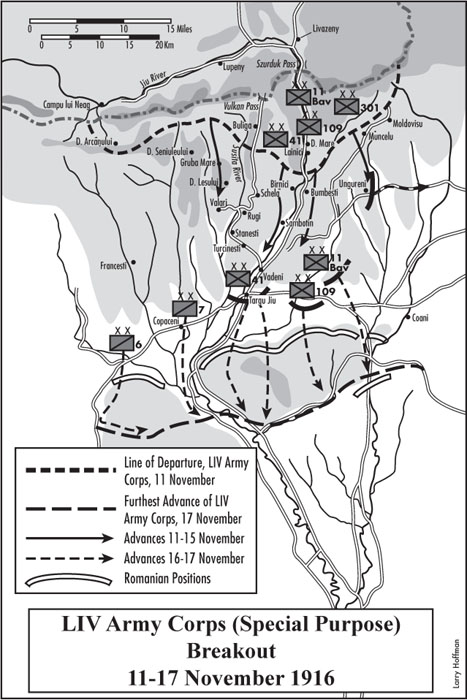

The soldiers of the 26th Prussian Infantry Regiment with their artillery started marching south toward Romania at 5 AM. The regiment belonged to the 109th Division. The division’s gunners had spent the freezing night bivouacked in the open, just to the east of the Lainici Monastery, the only spot in the Szurduk Pass wide enough to accommodate the horse park for the artillery. The infantry had slept bunched near the end of the pass. At 4 AM the night watch roused everyone, and they started south an hour later. The mounted artillerymen soon overtook the infantry. Confident in their preparation and objectives, the soldiers were singing marching songs as they trudged south. The practice proved infectious; once the following regiments and divisions got under way, they picked up the singing.1

A few miles to the east, separated by a ridge several hundred feet high, were the division’s other two regiments, the 376th and the 2nd Grenadier Guard Regiment. They had gotten under way at the same time. Their mission was to break from the mountains east of Bumbesti and fall on the flank and rear of the Romanian forces blocking the exit from the pass, while the 26th Regiment pushed through from the inside, catching the Romanian defenders in a crossfire. Along the roadway west of Lainici Monastery, the 152nd Regiment (known as the German Order Regiment, in honor of its Teutonic Knight forebears) of the 41st Infantry Division stood poised to punch through the Romanian lines west of Bumbesti. To keep the Romanians in the dark about the main thrust, a regiment from von Kneussl’s 11th Bavarian Division would descend from the snow-covered Vulkan Pass six miles to the west, marching on the village of Schela. The remainder of the Bavarian division was at the northern mouth of the Szurduk Pass, ready to enter once the operation began and the 41st and 109th divisions moved south, making room in the packed defile.2 West of the Vulkan Pass, the Württemberg Mountain Battalion would attack. The battalion had infiltrated to the edge of the Romanian lines, taking the enemy position at Gruba Mare on 7 November. The Romanians tried hard to retake the summit the next day, but Hungarian mountain artillery attached to the Württemberg battalion drove them off, the officer in charge muttering, “Mother Mary, please make this one a direct hit!” with every round fired at the charging Romanians.3

On the east side of the pass, the Germans staged a few attacks to draw the enemy’s attention. On the 10th, they took the Muncelu Massif,4 nine miles east of the defile and on the crest of the range above Stancesti, positioning them to block any enemy reinforcements coming from the Olt region. This was an extra precaution, because von Falkenhayn had ordered advances from Orsova, the Red Tower Pass, and the Campulung to begin simultaneously with Kühne’s, to tie up all the major Romanian formations.

By daybreak on the 11th, the combined artillery of the 109th and 41st Divisions and the 26th Infantry Regiment had reached the exit of the Szurduk Pass. The fog had dissipated around 7 AM, permitting the artillery to start firing at the Romanian fortifications, some of which had armored cupolas, opposite the pass. German 210mm howitzers shattered the cupolas.5 The 26th Regiment turned east and headed toward Stancesti, skirting the edge of the foothills. The 109th’s two other regiments, the 2nd Grenadiers and the 376th Infantry, descended from the crest of the ridge to link up with the 26th. On the opposite side of the Jiu River, the 41st Division had the mission of striking southwest toward Valari, driving the Romanians from the area between the edge of the mountains and the Jiu and freeing it for the passage of von Schmettow’s cavalry.

Attentive Romanian units from the 1st Division guarding the exit from the pass had noticed the German movements and activities the day before, but their reports did not elicit any response from their leaders, who were distracted by internecine squabbling.6 The Romanians let their guard down, and the appearance of masses of Germans took them completely by surprise.7 General headquarters immediately assigned General Dumitru Cocorascu to take over the 1st Division from its acting commander, Anastasiu, with orders to retake Valari and Schela. He was promised reinforcements as well.8 Romanian counterattacks were ineffectual, however, despite orders and exhortations to “fight to the last drop of blood in order to prevent the enemy from entering the Jiu Valley.”9 On the 12th, the Romanians still did not comprehend the size of the German operation. Vasilescu, commanding the 1st Army, thought that a strong counterattack from the 1st Division could restore the front.10

The German infantry had reached their objectives by the end of the first day. West of the Jiu, the 41st Division held the line of Lesulu-Schela-Birnici-Bumbesti along the foot of the mountains, and on the opposite side of the valley, the 109th had broken free, pushing east toward Stancesti. Berthelot’s chief of staff called the operation “a magnificent tour de force; a masterpiece of detailed preparation.”11

The secondary attacks elsewhere along the Transylvanian Front had likewise gone well for the Central Powers. Bolstered by the German 2nd Bicycle Brigade, Szivo, the Hungarian colonel, had moved from Mehadia down the Cerna River, capturing parts of Orsova. Krafft’s Alpine Corps kept up the pressure in the Olt Valley, turning back Romanian counterattacks at Mounts Sate and Furuntu and advancing down the Red Tower Pass. Below Brasov, von Morgen’s Ist Reserve Corps had taken Candesti.12

Von Falkenhayn spent 11 November at Petrosani, watching the troops head south into the defile. The movement of 60,000 soldiers accompanied by 30,000 horses through the twenty-mile cut captivated him. Particularly impressive, he thought, was the balancing act the group had to perform between the side of the highway with cliffs that rose almost straight up, and its opposite, where the racing Jiu River allowed no deviation. In many places, the ground was covered with rockslides. Expedient bridging crossed gaps where the road had fallen into the river.13 He was quite pleased.

The Romanians did not share the German view. Their 1st Division, responsible for defending the Jiu Valley, reported that its situation was critical. The enemy had reached the village of Shela, and his heavy artillery had destroyed the Romanian guns. Staff officers had a good idea of the Germans’ order of battle and likely objectives, prompting Cocorascu, the 1st Division’s commander, to ask if he could withdraw the detachment at Orsova to the interior. He pointed out that he had already authorized the evacuation of Targu Jiu and nearby towns.14 This latter step did not sit well with headquarters. Vasilescu sent a telegram asking Cocorascu who, if anyone, had authorized or approved the evacuation of locals, pointedly reminding him that the king’s orders called for holding the enemy in place with all available means for four to five days. Everyone was asked to make the supreme sacrifice.15

The next day, von Falkenhayn headed south down the pass. He set up a command post on top of a hill above Bumbesti to observe the units exit from the defile. The Romanians kept up a brisk artillery fire, aimed at the summit as well as at the mouth of the pass. The field gray columns emerged from the defile, wave after wave, then spread out and continued south or southeast. No one stopped, wavered, or hesitated, even though Romanian counterattacks pressed close to the mouth of the pass. “A single thought,” noted von Falkenhayn, “drove the entire mass of troops: out of the pass and at the enemy! … [We are] heading to a glorious victory.”16

Simultaneous with the drive through the Szurduk Pass, the Württembergers took the last major peak on the south edge of the mountains west of the Vulkan Pass – the Leselu. Their losses were negligible. They had a clear view of the Walachian plain, and they wasted no time sending patrols the next day into the villages in the foothills below them. The patrols returned laden with chickens, geese, bread, and brandy and bringing the good news that the enemy was nowhere to be seen. Taken by what seemed a virtual cornucopia, they called their service in Romania the “fat rooster campaign.”17

The staff in the Romanian general headquarters at Peris understood the importance of holding the Germans; if the enemy broke through the Transylvanian Alps, he would threaten all their defenses in Walachia. To block the Germans, they would have to commit the reserves that Berthelot had built for that purpose. The Frenchman had five divisions, but he estimated it would take eight days to move them where needed.18 That would take too long, and his only hope lay with the Russians. They had taken over the front in northern Moldavia from Prezan and had promised to send an additional four corps. They had also promised to start an offensive in that region on 13 November.19

In the midst of the mounting crisis on the Transylvanian frontier, Beliaev informed the king and his staff that the Russians could not begin their offensive until the 20th. Colonel Viktor Pétin observed sadly: “Never would a diversion have been more opportune!”20 Beliaev claimed that transportation was the problem. Bratianu was furious, noting that ten Russian corps were sitting on their hands at the Russian-Romanian border – a mere sixty-five miles from some of the fighting in the Carpathian Mountains. It would only take six days of marching at a leisurely pace to get there. Russian inactivity in the Dobrogea, he pointed out, had allowed von Mackensen to move many of his units back to Bulgaria.21 Beliaev refused to be baited. Romania was on her own for at least eight days.22

Von Falkenhayn’s strategy of placing pressure on the enemy at each potential crossing point now paid off. On the day of Kühne’s attack, cries for reinforcements poured into Peris from every direction. The 1st Army, responsible for defending the Jiu and Olt Valleys, felt the immediate pressure. Averescu cracked next. His 22nd Division reeled back toward Salatruc, prompting him to send an envoy, G. Dimandy, to the headquarters at Peris. Diamandy sought a division to replace the 22nd. The unit had now been in action for over two weeks, and its exhausted soldiers were close to the breaking point.23 Initially, Berthelot had turned a deaf ear to all the Romanian commanders and their demands for fresh units at the frontier.24 He did not want to commit his reserve too early, knowing that von Mackensen was gathering forces south of the Danube. The crisis at hand was one of the reasons why Berthelot had formed the reserve, however, and he would not be able to hoard it for long.

Bumbesti fell to the Germans on the 12th. The Romanians threw waves of infantry at the 109th Division all day from the southeast. The attacks were beaten back, but not without slowing the advance of the division as it moved east toward Stancesti. By nightfall, the 109th had taken Arseni, to the east of Bumbesti, and the 41st held a line running from Schela to Sambotin. The Württemberg Mountain Battalion was a few miles away on the Leselu Massif, awaiting orders to move into the Jiu Valley.25

Late that night, in pitch dark, the Württembergers descended from the massif. Their objective was the village of Valari, and they were in a tenuous position. Located beyond the extreme right flank of the LIV Army Corps, they had no friendly forces near them, and the line of communication to their base, on the opposite side of a snow-covered mountain range, extended thirty miles. In the morning, they watched a Romanian effort to envelop the right flank of Kühne’s corps unfold. The enemy thrust aimed at the 152nd Infantry Regiment26 a few miles to the east, but once the Romanians saw the Württembergers, they also became a target. The battle raged all day, and every soldier in the Württemberg Mountain Battalion and the 152nd Infantry recognized that this engagement would determine the success of the effort to break out of the mountains. The 152nd Regiment stormed the village of Schela and linked up with the Württembergers at Curpenel, just in time to see rows of field gray uniforms descending from the Vulkan Pass and heading toward them.

Von Kneussl’s Bavarians had arrived, and the Romanian attack faltered. By nightfall Valari was in German hands. The customary short entry in the 9th Army’s combat journal made note of the army’s progress against stubborn enemy resistance and the heroic defense of the Württembergers. The LIV Corps received orders to expand its bridgehead in Walachia by turning to the southeast, anticipating a crossing of the Olt River near Dragasani.27

The Germans expected to finish off the Romanian resistance on the 14th. They had fresh troops. The 301st Division and main body of the 11th Bavarian Division, following the 109th and 41st Divisions respectively, exited the pass on the 13th but had not yet been committed to any action. A fifth division, the 115th, was on the way to join the operation from a quiet sector of the Russian Front. Von Schmettow’s cavalry entered the Szurduk at 5:45 AM on the 14th. The moment they had long awaited was at hand: the breakout into the enemy rear. The troopers’ faces beamed with confidence; around the neck of each horse was a garland of hay, while hand grenades festooned the saddles. Their orders: advance south to Filiasi and interdict the rail lines in order to protect the right (south) flank of the LIV Corps.28

They made little progress. Below the pass, the Germans advanced only as far as Targu Jiu in horrible weather. Unrelenting rain turned the roads into rivers of cold mud, slowing everything. Kühne’s LIV Corps occupied a line from Targu Jiu northeast back toward Stanesti. At Orsova, Szivo’s Austrians had recaptured the town and driven the enemy east of the Cerna River, where they occupied substantial positions on high ground above the river. The Austrians made no further progress, however. On other fronts, things went better for the 9th Army. West of the Olt River, Goiginger’s 73rd Division had reached the heights above the Lotru River, and on the east side of the Olt, the Bavarians had carried Mt. Toaca. South of Brasov, both von Morgen’s and von Staabs’s corps crept forward.29

At his headquarters at Craiova, Vasilescu was in good spirits, reporting that all the formations in his army and the 14th Division (arriving near Curtea de Arges) were engaging the enemy. The overwhelming number of German formations in the Jiu region made that area his most threatened. To the west, the Cerna Detachment had but eight battalions (one a militia unit) holding along a front of twelve miles, and in light of potential threats, Vasilescu wanted to move back to more easily defended positions at Turnu Severin the next day. In the east, in the Olt Valley, his troops were blocking Krafft’s advances. All in all, Vasilescu felt that his men could hold for four or five days along his entire front. If the additional division promised by the general headquarters, the 17th, arrived on time, he thought he could launch a counterattack in the Jiu region.30

One reason for his positive mood came from the fact his forces had retreated to a formidable set of hills south of Targu Jiu,31 giving them the advantage of high ground. Vasilescu decided to make a stand on the heights,32 but he did not realize how badly outnumbered he was. He had just over one division (the 1st, with some elements of the 13th) while his opponents had five, and although he was expecting reinforcements from the 17th Division, these would not arrive until the 17th.33

Faced with Vasilescu’s willingness to fight, the Germans changed their plans. Von Falkenhayn had planned for the LIV Corps to turn east after reaching Targu Jiu, leaving the cavalry to head south to Filiasi,34 but Kühne and von Schmettow convinced him otherwise. Turning with the bloodied but unbowed Romanians on their flank in the heights south of Targu Jiu was too risky, and there was little to be gained. The roads were impassable. Kühne wanted to continue south to Filiasi before wheeling his corps toward Bucharest. That would require a frontal assault to push the Romanians from the heights above Targu Jiu. Kühne nonetheless felt the outlook was favorable because his forces outnumbered the enemy, and the single-track railroad running from Craiova to Barbatesti, the nearest railhead, would stymie Romanian efforts to rush in large numbers of reinforcements.35

Von Falkenhayn really had no choice but to go along with his corps commanders, even though he had wanted the cavalry to push south, screening Kühne’s infantry and advancing into the enemy’s rear areas. Von Schmettow’s riders did not have the strength to push aside the enemy by themselves.36

The decision to continue directly south surprised the OHL, which directed von Seeckt to see what was going on. He arrived at Targu Jiu on the 17th, and one look at how the awful weather had led to the rapid deterioration of the roads, especially those running to the east, convinced him that going south offered greater promise.37 He also believed that capturing the railroad running from Orsova to Craiova was essential for future operations. There was no arguing with his logic.38

Day-long storms on the 16th left a foot of snow in the valleys and more on the hills and mountains, obscuring observation and bringing everything to a standstill. The miserable weather did permit von Schmettow’s 6th Cavalry to disengage without the Romanians becoming aware of their movement around the west flank of their forces, and the Bavarian 11th Division advanced to the edge of Targu Carbunesti.39 The snow continued throughout the night, wreaking havoc with communications. On the 17th, the Germans pressed on despite the hardships. Their troops probed the Romanian lines and reported that the flanks appeared stronger than the center, so Kühne weighted his attack accordingly and struck there. The infantry of the 41st and 109th Divisions, along with some armored cars, drove back the Romanian 22nd Brigade from the center and center-right of their position, from Carbesti to Pesteana. Von Schmettow’s cavalry divisions, which had started around the enemy’s left flank in the storms, eventually turned it, sending the enemy in that area fleeing south. On the German left flank, the 11th Bavarian Division and the Württemberg Mountain Battalion remained in close combat with the Romanians all day. Pushed back by the Bavarians to their railhead at Barbatesti, where reinforcements from their 17th Division trickled in all day, the Romanians fought furiously. Nonetheless, with their center ruptured and their left flank turned, they had to retreat south and southeast the next day.40 The Germans claimed to have captured 71 officers, 3,400 soldiers, seven cannons, and seventeen wagons filled with ammunition. Their battle losses were close to 800, while the Romanians fared far worse, with 3,500 killed or wounded. Of greater importance, the Germans had opened the door to Walachia.41

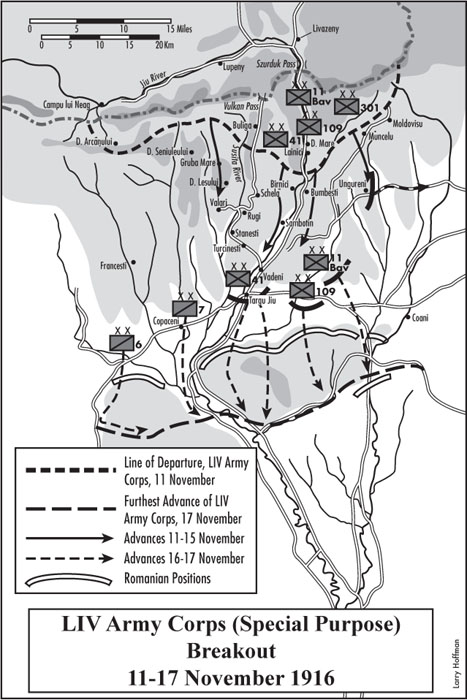

The defeat at Targu Jiu dictated that the Olt River would be the line of defense for Romania. For Vasilescu, that meant abandoning the region west of the Olt, and he ordered the detachments at Orsova and along the Danube42 to withdraw east toward Craiova and Caracal-Slatina, lest their lines of communication be severed. Berthelot begged Ferdinand, “in the name of the Entente,”43 to countermand the order, telling the Cerna Detachment to resist to the last man, destroying all the bridges and means of communications.

There was a purpose in what seemed otherwise to be a sentence of death or captivity for that formation. First, Berthelot planned to form a maneuver force from his reserve that would attack the Germans west of Slatina, in the region between the Jiu and Olt Rivers, and he needed time to assemble it. Consequently, he ordered the entire 1st Army, including the Orsova Detachment, to defend that area and fall back slowly, buying the needed time.44 Second, the east-west railroad across Romania connected at Orsova with another railroad coming from Timisoara, in Hungary. Berthelot knew that the Central Powers would find those railroads essential for supplying their forces south of the Transylvanian Alps.45 Leaving the detachment at Orsova would almost certainly ensure its destruction, but that move would also provide the opportunity to destroy the railroads and bridges in the area, lengthening the time it would take the Germans to put the railroad into operation. The king agreed, and the order to retreat was canceled. Szivo’s forces remained plugged up in Orsova for another week.46

The Romanian soldiers began their long trek from Targu Jiu toward the Olt Valley during the night of the 17th–18th, marching south and southeast and getting a jump on the Germans. The 1st Division withdrew along the Jiu River toward Filiasi and Craiova, while the battered 17th Division, a few miles to the east in the Amaradia Valley, followed a parallel course. Cocorascu of the 1st Division paid the price for failure. On the 18th, the Romanian general headquarters relieved him, putting General Gheorghe Spirescu of the 17th Division in charge of all operations along the Jiu. Anastasiu once again took over the division, leading the retreat south.47

At Craiova, the staff at the 1st Army had a reasonably good picture of their pursuers. Their only error was in thinking that the two German cavalry divisions were one. Vasilescu ordered his divisions into the area between Craiova and Caracal, which offered escape over the Olt River at three towns: Draganesti, Slatina, and Stonesti. The 1st Army abandoned its headquarters at Craiova and left for Slatina during the night of the 18–19th.48 The stress of what had been a calamitous week for Vasilescu began to show. In one of his periodic reports to the king, on the 20th, the general wrote that “the situation of the units and formations of the 1st Army in Oltenia [the western half of Walachia] is very worrisome … my assessment is that we have lost the power to fight back against the overwhelming strength of the enemy.”49

Von Schmettow’s cavalry and Kühne’s infantry went after the fleeing Romanians. Von Falkenhayn’s instructions to his corps commanders were plain and direct: pursue the enemy and weight the right flank of the advance as it neared Craiova.50 The two cavalry divisions initially rode west to the Motru Valley, then wheeled south toward Filiasu and Craiova. The 4th and 5th Bicycle Battalions came down the Jiu Valley, followed by the 41st Division. The 109th Division marched just to the east, along the Gilort River, and another six to twelve miles east of them came von Kneussl’s 11th Bavarian Division and the Württembergers. Traveling parallel to the south wall of the Transylvanian Alps was von Busse’s 301st Division and the 144th Austrian Mountain Brigade.51 Despite the weather – which alternated between rain, snow, ice, and fog – the Germans and Austrians made good progress, heading south into Walachia. They averaged about twenty-five miles per day, with everyone excited about being on the move.

The few accounts from the common soldiers all focused on the plentiful livestock, especially poultry. Albert Reich recalled that the “feathered game” was abundant, and the troops usually had a chicken for lunch and a goose in the evening. Pigs and piglets were snatched from the locals and disappeared quickly into the cooking pots of hungry German soldiers. The Württembergers thought they were in the promised land of milk and honey. The soldiers laughed at the few brave locals who protested, telling them to take it up with Bratianu.52

Forming the outside or western flank, and operating under the direct control of the 9th Army, von Schmettow’s cavalry had the greatest distances to cover. Portable radio units kept both the corps in touch with the 9th Army headquarters and the wide-ranging patrols in touch with the corps. Mobile artillery accompanied the troopers for firepower. To maintain momentum and speed, von Schmettow moved his 6th and 7th Cavalry Divisions – given the code names “Max” and “Moritz,” respectively – in a leap-frog manner. While one division rested, he would send the other forward until it ran into resistance or out of supplies. The resting division would then advance parallel to its stopped counterpart, bypassing the enemy and turning his flank, forcing him to retire. The technique worked, keeping the Romanian rear guard off balance. The two bicycle battalions occasionally accompanied “Max” and “Moritz,” but they usually functioned as the corps’s reserve, as did the section of armored cars. The mobility of the cyclists and cars allowed von Schmettow to deploy them rapidly to hot spots when extra help was needed.53

Once past the enemy’s flank at Targu Jiu, von Schmettow was in open country, performing long-range reconnaissance, flank security, and disruption. After months of stalemate, this was heady stuff. Nonetheless, as his troops raced southeast, von Schmettow kept nervously looking back over his shoulder, and he had one momentary scare. He had left one squadron behind as a safeguard, and that unit reported contact with three enemy battalions, a substantial force. Along with a battery of artillery, these battalions had come from the detachment at Cerna. A Romanian task force, led by Colonel Tautu, had left Turnu Severin on the 16th and marched to Baia de Arama, where the German cavalry discovered it.54 Von Schmettow paid little attention, but on the 18th, when Tautu’s force attacked his baggage trains, he halted his drive south and sent the 7th Cavalry Division to get rid of the troublesome intruders. The 7th Division engaged Tautu’s force at Rasci. The fight lasted until dark and resumed the next morning. Although the Romanians suffered heavy losses – over 500 of them were taken prisoner – a combination of fog, mountainous terrain, and a poorly executed flank attack by General Friedrich Studnitz’s (1863–1932) 5th Brigade allowed most of them to escape. They fled back toward Orsova, followed by three German cavalry squadrons under the command of Colonel Kurt von Rex (1863–1947).55

Von Schmettow’s divisions next rode southwest until they reached the Motru River, running west of and roughly parallel to the Jiu, which it joined a mile north of Filiasi. Once at the Motru, “Max” and “Moritz” turned south, riding hard and encountering negligible opposition. The two divisions passed west of Filiasi. “Max” was in the lead and entered Craiova at 8 AM on 21 November, joined there later in the day by Schmidt von Knobelsdorf’s fast-marching 41st Division. The cavalrymen had driven out a small detachment of Romanian rear guards, taking some 200 prisoners, but the bulk of the enemy’s force was long gone, having retreated east to safety across the Olt River. The Germans pursued but soon encountered stiff opposition.

That night scouts from Cuirassier Regiment No. 2 reported that the area east of Craiova to the Olt River appeared free of the enemy. Von Schmettow immediately ordered his two divisions to sweep the area south of the Craiova-Slatina railroad to the Danube River. “Max” led the way, and “Moritz” followed close behind, mopping up where the leading elements had bypassed enemy stragglers.56

The infantrymen of the LIV Corps pressed hard along the muddy and often frozen roads, staying right on the heels of their mounted comrades. Tramping alongside the soldiers were masses of refugees – either fleeing their homes or returning to them. Many walked barefoot in the mud, their few possessions wrapped in a bundle on their heads. Mothers with babies, children, and the elderly rode in wagons hauled by oxen or buffaloes. Herds of livestock accompanied them.57 The 41st and 109th Divisions marched along the Jiu River in that order, while the 301st followed the Olt River. The 11th Bavarian Division went between the two columns traveling alongside the rivers, generally following the track of the retreating Romanian 17th Division. Once it reached Craiova, the 109th Division continued in a southeast direction toward Caracal, while the 41st swung east and headed toward Slatina, on the Olt River. At the village of Tels, about halfway from Craiova to Slatina, the Bavarians joined the column. The 301st Division had turned east at Otetelisu and was advancing on Dragasani, the next town with a bridge north of Slatina.

By nightfall on the 21st, all of the divisions were east of the Jiu and closing in on the Olt. As von Falkenhayn noted, events had proved the old adage that masses of cavalry, even when forcefully led, did not move much faster than the infantry. The weather and road conditions had worn out the troops and animals, however, and von Falkenhayn allowed the soldiers a day of rest on the 22nd. He could not offer that luxury to von Schmettow’s corps, although the men and horses showed unmistakable signs of exhaustion. Von Falkenhayn knew that keeping pressure on the retreating Romanians increased the likelihood of mistakes by them, and thus opportunities for the Central Powers. He ordered von Schmettow’s riders east to the Olt.58

The German rest day gave the Romanians a breather to organize their forces on the west bank of the Olt. As they approached the Olt, Vasilescu assigned the 1st Cavalry Division59 to safeguard the baggage trains and the artillery heading for the bridges at Slatina and Stoenesti. The cavalry division commander, General N. Bottea, designated “corridors” leading to the bridges and placed his 1st Brigade at Slatina and his 2nd at Stoenesti. He told his 2nd Brigade commander to assign a squadron from the 9th Cavalry Regiment to guard the bridge. The squadron had a demolition team, but the bridge was not to be destroyed without specific orders. Anastasiu steered the remnants of the 1st Division toward the two corridors and safety on the 22nd.60

At Peris, the mood was glum. The German penetration into Walachia had forced the general staff to commit the general reserve in a piecemeal manner, vitiating its effectiveness. Instead of holding the enemy at the mountain barrier, where the reserve could spell units on that line, the general headquarters now faced the nightmarish task of defending what had become an enormous salient in Walachia. Von Falkenhayn was pressing from the north, and von Mackensen was certain to cross the Danube – the only questions were when and where. If either flank folded, the center could not hold. One by one, the formations that Berthelot had so painstakingly put together went in different directions. The 8th Division went to Pitesti. The 17th Division, sent to plug the gap at Targu Jiu, arrived in stages because of limited transportation and was consequently shattered without affecting the outcome. By 22 November, the 1st and 17th Divisions were referred to in orders as a combined unit. Together the two had a total of only 8,000 infantrymen. A day later that number had fallen to 6,500.61 The 1st Division was by far the worst for wear, having been on the front longer, but the merger of the two was a sure sign that neither could stand on its own. There were still three divisions remaining in the general reserve, but Berthelot now had to consider the possibility that he might need them to defend the capital.62

Berthelot proposed to Ferdinand on the 20th that the reserve should be committed along the Olt River to scatter the enemy forces as they emerged from the Jiu Valley. Berthelot wanted to hit Kühne on the west side of the Olt, opposite Slatina, before the Germans could cross the river. Berthelot insisted that his favorite, Prezan, should be in charge of this effort. The monarch agreed. But Beliaev made a stunning countersuggestion at the daily briefing on the 22nd. The Russian proposed retreating east of the capital to prepared positions, generally along the crest of the Carpathians from the Bucovina to Focsani, then running from there along the Sereth River to the Danube, a reiteration of what Alekseyev had suggested to the startled Berthelot at Moghilev. From a purely military perspective, the proposal made sense.

Berthelot opposed this strategy, which would surrender the wealth and resources of the country’s richest province and its capital to the Central Powers without a struggle. “A debacle without fighting,” as the French general called it, would certainly shatter the morale of the army and lead to a collapse.63 He defended his proposed commitment of his reserve, pointing out that the Germans had outrun their supplies and heavy artillery, and that if they attacked without waiting for those to catch up, the Romanian infantry would actually outnumber them. Berthelot said that if he could attack within four days, he could guarantee that he would keep control of the right bank of the Olt and would push the Germans as far back as Craiova.

Everyone looked at the monarch, knowing that the moment of decision was at hand. Ferdinand agreed with Berthelot.64

Prezan and his talented operations officer, Captain Ion Antonescu (1882–1946),65 arrived at Berthelot’s room at Peris at 5 PM on the same day, the 22nd, for instructions. Berthelot briefed the two on his concept for stopping Kühne, and in a melodramatic scene, Prezan pledged to “do all that is possible. God willing!”66 Accompanied by Pétin, Prezan and Antonescu left immediately for their new assignment, arriving the next morning at the 1st Army headquarters at Pitesti. There they discovered that the situation had changed completely: the Germans had crossed both the Olt and Danube Rivers.

In the zone between the Jiu and Olt Rivers, Kühne’s infantry and von Schmettow’s divisions resumed their advance on the 23rd. The 41st and 109th Divisions tried to converge on Slatina and its bridge, but the roads were so bad that the two divisions had to remain on the same road, one behind the other. The Bavarian 11th Division soon joined the column. The 41st led the way, and the Romanians put up a hard fight, bringing the Germans to a halt twelve miles west of the Olt. At Robanesti, in an episode that Kühne called “madness,” the 3rd Squadron of the 7th Romanian Cavalry Regiment actually charged the Bavarian infantry on horseback and was wiped out to the last man.67

The Germans had much better luck in the south. The 6th Cavalry Division rode toward Stoenesti and its bridge over the Olt, with orders to go beyond it to Caracal. At Stoenesti, they got a patrol across the bridge in midafternoon, after the Romanians failed to blow up the bridge.68

Hearing of that disaster, Anastasiu, the commander of the 1st Division, ordered the 2nd Cavalry Brigade commander to destroy the bridge before more Germans crossed.69 Anastasiu’s information was dated. Romanian engineers had already tried to blow up the bridge but hadfailed because of problems with fuses. The Germans captured the partially destroyed hundred-yard bridge. The two squadrons sent by Anastasiu tried to retake it, but the Germans held on,70 breaching the center of the Romanian defenses in Walachia.

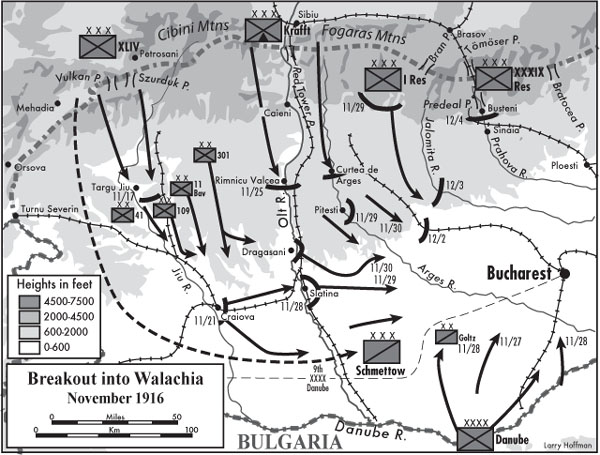

The German and Austrian High Commands had been planning to cross the river since July. Conrad had staged his army’s bridging equipment at the Belene Channel, which was protected by the monitor fleet. The operation could not begin until the enemy was driven from Transylvania and the Dobrogea. By November, the 9th Army’s success in Siebenbürgen and von Mackensen’s triumph in the Dobrogea made it clear that the OHL and AOK could look forward to a combined attack on Bucharest. Ludendorff asked von Mackensen about crossing the Danube. He responded that he could push over to the opposite side as early as 7 November, but he could not expand beyond a bridgehead until reinforcements arrived, scheduled for the middle of the month. From the north, von Falkenhayn indicated he planned to break out over the mountains and emerge into Walachia near Targu Jiu, but also not until the middle of the month.71

Armed with that information, von Mackensen stepped up his preparations. He had already placed General Robert Kosch, the LII Corps commander, in charge of the crossing operation. Kosch had considerable experience. Troops under his leadership had bridged the Dniester in Russia and the Danube at Belgrade. Around mid-September, Kosch’s staff had selected the crossing site at Sistov, precisely where the Russians had crossed in the war against Turkey in 1877–78. The Danube current was slower there, and the distance to the Romanian shore was less than at most points along the river. On the Bulgarian side, the riverbanks were much higher and dominated the flat Romanian shoreline. The Germans could position their artillery and ammunition without being observed, and the high banks would conceal their infantry. Railroads came from the interior of Bulgaria, allowing the movement of the heavy artillery and ammunition, and the nearby Belene Canal behind Persin Island was the base for the Austrian Danube Flotilla and its bridging materials. Von Mackensen’s engineers constructed a narrow-gauge horse-drawn railroad from the Belene Canal to Sistov to allow the movement of the bridging materials. In front of Zimnicea lay Bujorescu Island, separated from the Romanian mainland by a causeway. Between the island and the riverbank was the harbor of Zimnicea. If the Central Powers could secure that island, they would shorten considerably the distance they had to bridge.72

On the Romanian side, the defenders were overextended. The Danube Defense Group was under General Constantine Christescu (1866–1923), a former deputy chief of staff of the army. He was responsible for an enormous sector, running from the juncture of the Olt River with the Danube, near Turnu Magurele, to the city of Calarasi in the east. Christescu had two divisions, the 18th Infantry and the 2nd Cavalry. The 18th had divided the area into three zones: Turnu Magurele, Giurgiu, and Oltenita. The division commander, General Alexandru Referandaru (1866–?), had three additional brigades of cavalry, and he assigned one to each zone. The bulk of his infantry, however, consisted of reserves and militia called to duty after the Romanian mobilization. They had obsolete weapons. Only one regiment, the 20th, was an active duty one. The 2nd Cavalry Division near Bucharest constituted the reserve for the Danube Defense Group.73 The Romanians were stretched thin.

German reconnaissance indicated that only a pair of Romanian battalions provided river guards at Zimnicea. Inland, there were three or four batteries and some cavalry. Few Romanian aircraft ever flew over Sistov and the proposed crossing site, and the ones that did were easily driven off by anti-aircraft fire, allowing preparations to proceed undisturbed and unnoticed. From all appearances, the Romanians did not expect anything to happen here.74

On the 13th, von Mackensen issued the order for the assault and crossing, scheduling it for the 23rd. The landing force would come from the 217th German Division and a division-size group of German and Bulgarian Landsturm units under the 33rd Cavalry Brigade commander, Brigadier General von der Goltz.75 The strength of these units did not match their titles. The 217th, a recently formed division now led by General Kurt von Gallwitz (1856–1942), had only two regiments. The division’s third regiment, the experienced 45th Infantry, which had fought with distinction in the Dobrogea campaign, was sent by the OHL to Thesssalonica to stem an advance by Sarrail’s forces.76 Von der Goltz’s “division” existed more as a name than as a division.77 The value of the veteran Bulgarian 1st Division was questionable due to its losses in the Dobrogea. Especially problematic to von Mackensen was the brand-new Turkish 26th Division. After inspecting it, he said: “It did not inspire confidence, either from external appearance nor what its training showed … reservations existed as to whether the soldiers know how to use their arms. Clothes and kit were a disaster. Worst was the shortage of officers.”78

Even less impressive was the corps artillery. An odd collection of German, Austrian, and Bulgarian artillery was placed under the command of Colonel Richard von Berendt. All told, von Berendt had command of sixty-four batteries, nineteen of which were heavy. Among them were four batteries of the famous Austrian and German monster mortars. The Austrian Bridging Group had considerable experience, having crossed the Danube and Save Rivers in the 1915 campaign.79

Von Mackensen told the OHL he would conduct the crossing on 23 November. He was sanguine about the outcome: the odds for this crossing were much better than those for the one at Belgrade the year before. He expected less resistance and had a lot of heavy artillery, although fog threatened its effectiveness. General Stefan Neresov, commander of the Bulgarian 3rd Army, had matters safely in hand at the far end of the Dobrogea. Finally, von Mackensen gave credit for the successful completion of preparations to his chief of staff, General Tappen, who produced surprise after surprise.80

At 7 AM on the 23rd, in thick fog, Austrian combat engineers piloting small craft landed a Jäger battalion from the 217th Division on the north bank of the Danube, just to the west of Bujorescu Island. A few rifle shots rang out. The boats returned to pick up their second load, the Austrian 2nd Jäger Border Guard Battalion. As the vessels approached Bujorescu Island, artillery fire began to land in the water, but it had little effect because the fog prevented the Romanians from seeing their targets. As the fog dissipated, more boats of all sizes and shapes, protected by the Austrian monitors, began to ply the waters. By midday, the combat units from the 217th and von der Goltz’s divisions were safely in Romania. The Romanian guards, two companies of militiamen, were badly outnumbered and fled north.81 By the end of the day, a total of seventeen battalions were across the river, and the landing area was secure. The Austrian engineers began assembling the bridge. After crossing with Tappen, von Mackensen telegraphed the kaiser to report: “Danube crossing Sistov-Zimnicea has succeeded.”82

Two hundred miles to the north, when he heard of von Mackensen’s triumph, von Falkenhayn recognized at once that the successful crossing had made it impossible for the Romanians to hold along the Olt River. That left only the question, he wrote, of whether the enemy could still assemble a force near Pitesti capable of stopping his operations.83

The next day, von Mackensen and Kosch watched the Austrians at work, while the Bulgarian infantry, fortified by martial music from their bands to overcome their fear of water, were ferried across the river. Late that night, the Austrians finished the bridge and opened it to traffic.84 Reports from the north side of the river flowed back, confirming both that the units advancing inland were making good progress and that the crossing had taken the Romanians by surprise. During the 25th, the artillery went across the bridge, followed by the Turkish 26th Division. Von Mackensen directed Kosch’s LII Corps (the 217th, 12th Bulgarian, and 26th Turkish Divisions) to advance to the northeast, keeping “its feet” in the Danube, while von der Goltz’s riders went due north toward Alexandria, hoping to meet their comrades from von Schmettow’s cavalry there. Von Mackensen advised the OHL of his progress. Von Hindenburg responded, naming him the commander of all forces within Romania and designating the formations that had crossed from Bulgaria the “Danube Army.”85

The Romanian defenders, spread out over sixty-five miles, could not respond to von Mackensen’s crossing. With the bulk of the 18th Division’s formations scattered along the river, the German landing had cut the division in two. The advancing Germans shouldered aside the third of the division west of Zimnicea, while to the north and east the fast-moving Bulgarians scattered the rest. The general headquarters at Peris ordered the 2nd Cavalry Division to assemble north of Zimnicea to delay the enemy advance, while the 21st Division was moved to block the Alexandria-Bucharest highway, a maneuver that would take until the 27th.86

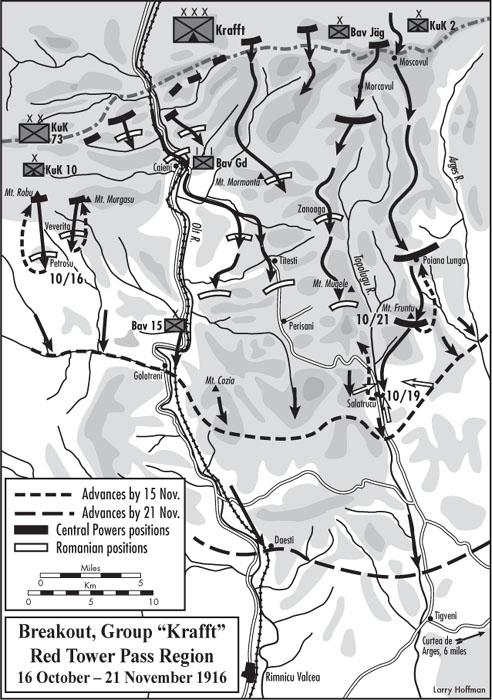

By the 24th, the Central Powers had penetrated the proposed Romanian defense line at two locations: from the west at Stoenesti, on the Olt River, and from the south on the Danube at Zimnicea. In the north, along the upper Olt Valley, the Romanian I Corps, with three divisions (the 13th, 14th, and 23rd), held a line east of the Olt and above Rimnicu Valcea and Curtea de Arges. Opposite them was Krafft’s corps.87 The 216th German Infantry Division led by Brigadier General Detlef Vett (1859–1927) joined Krafft’s formations (the Alpine Corps Division, the 73rd Austrian Division, and the 2nd and 10th Austrian Mountain Brigades) on 7 November.88 The Alpine Corps had started its latest drive to the south simultaneously with Kühne’s breakout, but the mountaineers found the going slow. The Romanians fought tenaciously, taking advantage of the positions they had constructed along the border before the war to slow the German progress. What troubled Krafft was his men’s tendency to rely on their artillery and feel pleased if they seized one enemy position per day, a tempo that in his mind meant they would never break through. In an admonition to the entire corps, the frustrated general pointed out that although the Romanian positions were challenging, they did not rise to the degree of difficulty presented by French fortifications that many of the soldiers had encountered on the Western Front. He urged his commanders to set more ambitious goals, relying less on long artillery bombardments and more on swift infantry assaults.89

The Germans and Austrians encountered nightmarish logistical problems in getting supplies to the front line. The horses that the artillery units had brought from home were not up to the task. They could not climb the grades, placing a greater burden on the supply columns, which had to rely on requisitioned local animals and drivers. Villages had to provide teams of animals with guides, but to avoid overburdening them, they were pressed into service for only two days and then released. Most of the drivers were women and old men, who could not tolerate the higher altitudes when the snow was heavy. The average load for each horse was 130 pounds, which meant an animal could only carry three to four rounds of 77mm artillery ammunition or four to five rounds of the lighter and smaller 75mm caliber. That was not much, since in close combat a good gun crew might get off ten rounds per minute. Transfer or relay stations helped, but veterinarians had to establish animal hospitals and aid stations on the main supply routes.90

The Alpine Corps’s rate of advance remained sluggish, but each day netted a substantial number of enemy soldiers and equipment. During the first two weeks of November, Krafft’s units captured 80 officers and 7,000 soldiers, along with twelve artillery pieces and twenty machine guns. As the Romanian losses mounted, reinforcements were required, and the 14th Division arrived opposite the Alpine Corps on 10 November. Their problems in the south prevented the Romanians from dispatching more troops to the north, which forced them to merge the 13th and 23rd Divisions. On the 20th, the Bavarians reached the villages of Calimanesti and Salatrucu,91 leading to far more optimistic entries in the 9th Army’s daily situation reports. On the 25th, Krafft stated that the enemy resistance in front of his corps was broken. His divisions were on the Curtea de Arges-Pitesti highway, marching toward the latter city.92 Von Falkenhayn noted his satisfaction in the army’s combat journal. He was confident the middle section (under von Morgen) of his forces still in the mountains would soon join Krafft’s corps, and he ordered Krafft to take Pitesti, which would force the Romanians blocking von Morgen at Campulung to withdraw.93

Von Staabs’s and von Morgen’s corps had faced Aversecu’s 2nd Army in the passes leading south from Brasov since mid-October. Opposite von Staabs were the Romanian 10th and 16th Divisions at the Predeal Pass, the 4th at the Bratocea, the 3rd at the Tatarhavas, and the 6th at the Buzau. Von Staabs’s corps made no progress, but it did keep four enemy divisions tied up. In front of von Morgen, the Romanian 12th and 22nd Divisions had initially kept the Germans and Austrians blocked in the Bran Pass, but the 8th Austrian Mountain Brigade had turned the enemy flank, allowing von Morgen’s units to enter the Campulung basin, where a tenacious Romanian defense kept them from closing on Dragoslavele.

On 12 and 13 November, the 28th Regiment of the 12th Bavarian Division (von Morgen’s I Corps), accompanied by some Austrian mountain artillery and infantry, marched for miles into the trackless mountains to turn the Romanian flank west of Albesti, taking the enemy by surprise. Recognizing that a breakthrough at Campulung would threaten the entire front, the Romanian general headquarters promised to send Averescu reinforcements it could ill afford – namely, the 21st Division, which was then unavailable for the 1st Army’s efforts to staunch Kühne’s penetration far to the west.94

The Germans, however, could not hold on to their gains. Ferocious snow storms made it impossible to get supplies to the units, which meant Albesti had to be abandoned. The Romanian general staff countermanded their orders, and the 21st Division remained near Bucharest. Undaunted, von Morgen kept up the pressure, taking Zanoaga on the 20th.95

The Romanian effort to hold off the Germans north of Bucharest collapsed in the last week of November. Krafft’s Alpine Corps broke free of the mountains on the 25th, beginning an advance on Pitesti. Von Morgen suggested that the Alpine Corps could do more to drive off the enemy in front of him by attacking Campulung instead of Pitesti. The 9th Army agreed and ordered Krafft to send some of his forces in that direction. The Romanians had already decided to withdraw. When von Morgen determined that the Romanians had abandoned their positions and headed south, he immediately followed. The OHL directed his corps to advance on Pitesti.96 The Central Powers had ruptured the northern flank of the Romanian defenses.

Von Falkenhayn kept up the pressure and the speed of his drive. Both were important. Closing in from several directions hindered or even prevented the enemy from shifting reserves, and the rapid advances kept the enemy off balance. By the time the Romanians determined where Kühne’s or von Schmettow’s columns were and designed a plan of action, their plans had been overtaken, since the Germans had moved another dozen miles forward. An example of the Romanian disorientation came when the French Count de Kerkhoven, departing in an airplane from Bucharest at 2 PM on the 24th, landed at the garrison field in Caracal. The count was flying to the 1st Army. Authorities in Bucharest had assured him the Germans were no farther than Craiova, fifty miles to the west, but the count found himself surrounded and captured by German horsemen.97

While his two army corps in the north breached the Romanian defenses, von Falkenhayn expanded the bridgehead at Stoensti. Von Schmettow’s lead division, the 6th, was at Mihaesti, halfway from Stoenesti to Rosiori de Vede. Von Falkenhayn wanted the LIV Corps to clear the area between Slatina and Stoenesti, with the 41st crossing the Olt in the former city and the 109th crossing in the latter. The two divisions would come together again on the east side of the Olt, attacking in the direction of Beuca and Ungheni. The execrable condition of the highways west of the Olt forced modifications to that plan. The 41st, 109th, and 11th Bavarian Divisions ended up following one another to Slatina, driving off Romanian counterattacks. To the north, the 301st Division had a highway to itself and marched into Butari, headed for the Olt crossing at Dragasani. Looking to the west and south, von Falkenhayn ordered Szivo to run down the Romanian Orsova detachment, while von Rex’s cavalry and the bicycle brigade were to advance to Craiova along the highway, securing the railroad that ran alongside it.98

Although von Schmettow’s cavalry had crossed the Olt, neither of Kühne’s lead divisions, the 41st and the 301st, had crossed the river by the 25th. The 41st had arrived opposite Slatina, only to discover that the Romanians had demolished the bridge. In addition, the river had overrun its banks. The bridging trains had not arrived but were expected that night. Aerial reconnaissance revealed that the Romanians planned to make a stand there, leading von Falkenhayn to direct Kühne to send the 109th and, if necessary, the 11th Bavarian Divisions over the bridge at Stoenesti. Von Schmettow’s cavalry had already crossed there, and he reported that the enemy was poorly disorganized east of the river. He urged crossing the Olt as rapidly as possible to exploit the enemy’s confusion. Kühne, whose two northernmost divisions faced a contested crossing at Slatina, favored a more cautious approach. Von Falkenhayn knew that a speedy tempo would paralyze his opponents, and he directed the bulk of von Schmettow’s two divisions north, along the east side of the Olt, to pressure the Romanians from the rear. Once the rest of the LIV Corps had crossed the Olt, von Schmettow could head southeast.99

A Romanian cavalry division blocked von Schmettow’s troopers from reaching Slatina. Meanwhile, the 41st Division had seized the railroad bridge, but fierce resistance kept the division on the west side of the Olt. The 11th Bavarian Division and the Württembergers had followed on the heels of the 41st, and when that division could not get across the Olt, Kühne ordered the Bavarians to try north of Slatina. He anticipated that he would save more time with this operation than having them march to the secure crossing at Stoenesti. That proved false, and the bulk of the division eventually had to march south to Stonesti, losing a day.100 The 301st ran into similar resistance at Draganesti. Only at Stonesti did any of the LIV Corps’s units get across the Olt on the 25th. After a discouraging day, however, aerial reconnaissance reported that the Romanians were burning supplies at Slatina, a sure sign that they intended to retreat. The Germans discovered the next morning that the Romanians had abandoned Slatina, and the 41st crossed that day.101 Also on the 26th, a squadron from the 6th Cavalry Division made contact at Rosiori de Veda with some of von Mackensen’s cavalry patrols.102

The Romanians faced three columns rapidly converging on the capital, leaving them with only one course of action to save Bucharest. They had to crush the German forces one at a time before they could unite and bring their overwhelming numbers to bear.

Kühne had the largest force, and he stood just east of the Olt. To the north, Krafft’s and von Morgen’s corps had emerged from the mountains. The smallest enemy column, von Mackensen’s, was southwest of the capital. Berthelot, directing operations for the Romanians, had no choice but to attack von Mackensen first. The Danube Army was also the closest to the capital, posing an imminent threat. The drawback to this plan was that most of the forces that Berthelot had assembled for the defense of the capital were to the west and northwest.103

Bucharest was the brains and heart of the kingdom. Berthelot knew he had to mount a defense: to abandon the city without a contest would signal the defeat of the nation. Bucharest’s forts were obsolete and had long been stripped of their guns. The battle would have to take place outside of the city, and the only geographic barrier of any sort was the Arges River, which ran northwest to southeast twelve miles west of Bucharest.104

An advantage to concentrating defense forces near Bucharest was the proximity to the Russian Army of the Danube, which Berthelot expected would come to his aid. But transportation problems bedeviled the Russians. The railroads were overwhelmed, burdened with the task of evacuating both Bucharest and Walachia, as well as moving Romanian units. Romanian paranoia led them to believe that Russian train commanders took too long to load and unload,105 an attitude that infected Berthelot as well. More unsettling was the growing conviction in the Romanian headquarters that the Russians were using the crisis to set themselves up to profit from Romania’s misfortunes. Immediately after Beliaev held the first meeting for the officers of his military mission, on 25 November, one of the attendees whispered to Berthelot that the Russian general had told his audience that “we have not come here to fight a war,” prompting the Frenchman to scribble “then why [did you come]?” in his journal.106 Suspicions grew when Beliaev told the king and the Romanian staff on the 26th that when he had asked Stavka to send the Russian VIII Army Corps and the 40th Division, Alekseyev replied, “Not one man; not one cannon!”107

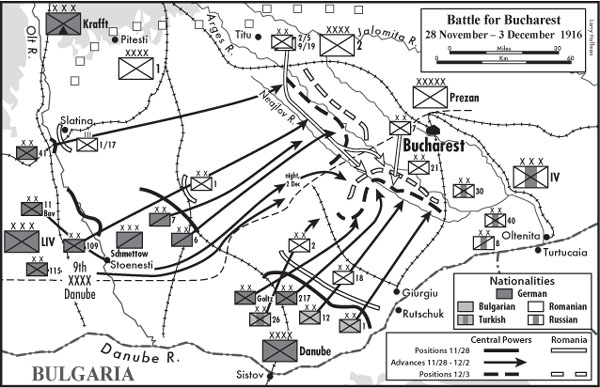

On 25 November the Romanian general headquarters placed Prezan in charge of defending the capital and gave him control over all Romanian forces except for Averescu’s 2nd Army and what was left of the North Army, now under General Constantin Christescu. On the evening of the 26th, Prezan went to Peris and disclosed his plan to Berthelot. He intended to defeat the enemy forces one by one, starting with von Mackensen’s army – then advancing on the capital from the southwest – while blocking the Austro-German drive of von Falkenhayn from the north and west.

Kühne’s LIV Corps and von Mackensen’s Danube Army presented the immediate threat to the capital. Von Mackensen was far out in front because of the sluggishness of the LIV Corps in getting across the Olt.108 His left or northern flank, however, would be exposed until Kühne arrived to make contact, giving Prezan his only chance at success. He had to prepare quickly and strike very hard.109

Prezan issued his orders the next day. To stop the enemy advance on Bucharest, he said, “I intend to take the offensive.” The 2nd Army would continue to protect the passes leading south from Brasov. He directed the 1st Army, led by General Dumitru Stratilescu,110 to form a giant screen from east of Curtea de Arges southwest to the Olt River, then south to Slatina, to stop the enemy advance toward Pitesti and Costesti. Success rested on preventing the forces of Kühne and Krafft from converging on the capital. The 1st Army, Prezan stressed, could fall back under pressure, but it had to remain in contact with the left flank of the 2nd Army.

He assigned the Danube Defense Group (the 21st, 18th, and 7th Divisions) under General Ivancovescu responsibility for halting von Mackensen’s columns west of the Arges River. These divisions formed the “anvil.” The 9/19th and the 2/5 Divisions, his “hammer,” were to disengage from their blocking positions along the Olt and march along the Neajlov River toward the capital, attacking the exposed left flank of von Mackensen’s Danube Army. These two divisions, hastily formed from the four former shattered divisions of the same designation, were in poor shape.111 Prezan kept the 10th Division, being reconstituted between Ploesti and Titu, and the 1st and 2nd Cavalry Divisions as a reserve.112

On the 29th, Berthelot outlined to the king the array of forces that Prezan was assembling for the defense of the capital. Beliaev next reported that Stavka had agreed to send the IV Corps, now in the Dobrogea,113 to help in the defense of Bucharest. On top of that, Stavka would send three more corps and three cavalry divisions. The briefing ended on a sour note when Beliaev repeated his suggestion to retreat to the line of the Sereth River.114

Prezan’s plan began to break down as soon as it started. The Austro-German forces were simply moving too fast, and von Falkenhayn had no intention of slackening the pace. With every step forward, his formations would force the Romanians into a narrowing space that simultaneously lessened his own front. The OHL, convinced that the bulk of the Romanian divisions were still in the mountains, told von Falkenhayn on the 28th to swing the LIV Corps to the northeast, which would bring it into the rear of the Romanian forces facing von Morgen and von Staabs. This move required Kühne’s divisions to fan out.115 The modest change in direction did not then seem important because the LIV Corps had not made contact with the enemy since crossing the Olt. Von Falkenhayn planned to send von Schmettow’s cavalry into the Arges Valley across the front of the LIV Corps, hiding the corps while discovering information about the enemy. Von Falkenhayn was unhappy with his intelligence. He bemoaned the incomplete picture he had concerning the movements of the Romanians.116

In the south, what little resistance von Mackensen’s Danube Army ran into after the river crossing was easily swept aside. On the 27th, a Bulgarian force crossed the Danube from Rutschuk and took the city of Giurgiu. Right behind them came General Josef Gaugl (1859–1920) and his Austrian engineers, who began setting up a second pontoon bridge capable of bearing heavy traffic. Capturing the city and its port eased von Mackensen’s logistical situation immensely. The Central Powers now had complete control of the Danube, “the most effective traffic route of the Romanian war zone,” right up to Giurgiu, south of Bucharest. Two railroads ran from Giurgiu into the interior: one to Craiova, the other to Bucharest.117

Inland, the advance elements of the 217th Division ran into strong enemy forces near the village of Prunaru. Only with the arrival of heavy artillery around noon on the 28th were the Romanians driven back. The division captured 700 soldiers and twenty guns, then halted. A few battalions moved to Naipu, where they came across more Romanians. Von der Goltz’s cavalry division tried to provide a screen between the 217th Division and the 9th Army, but that proved impossible as Kühne’s corps moved northeast, opening the gap between the two armies.118

Von Falkenhayn felt that Bucharest would soon be his. The Romanians’ only hope for holding the capital, he believed, depended on getting reinforcements from the Russians, and he was almost certain time had run out for that. The question was whether the Romanians would risk battle before being forced to give up the capital. He still hoped to envelop their army, but he could not yet determine from which direction that would be possible – from the south, with the 11th Bavarian and 109th Divisions advancing toward Bucharest, or from the mountain side of the capital, the objective of the remainder of the LIV Corps.119

Von Mackensen was convinced that the Romanians would stand on the Arges River and that the Russians would be there as well. His men had already run into Cossack patrols. Accordingly, he told the OHL on the 29th that he had ordered his heavy artillery with some of the Austrian monster mortars, the “Skinny Emmas,” to cross the Danube at Giurgiu and move toward Bucharest.120 Worried that his and von Falkenhayn’s armies were drifting apart in the face of an enemy threat, he asked the OHL for the 115th and 11th Bavarian Divisions.

The OHL turned down him down the next day. Like von Falkenhayn, the OHL regarded the enemy center of gravity as somewhere north of Bucharest. Angered, von Mackensen sent a private telegram to von Hindenburg, asking for a public sign of confidence in his leadership. Von Hindenburg replied that von Mackensen certainly enjoyed his support and offered him a German division.121

On the 30th, von Falkenhayn received reports from his cavalry that the Romanians were marching across the front toward the left flank of von Mackensen’s Danube Army. Although these Romanian units later proved to be Prezan’s “hammer,” the 2/5 and 9/19th Divisions, the 9th Army commander was not alarmed. He thought that the 26th Turkish Division and von der Goltz’s cavalrymen would provide adequate flank protection for von Mackensen.122 That conviction grew the next morning, when the headquarters received some critical intelligence. In the early hours of 1 December, one of Krafft’s units had captured two Romanian staff officers from the 8th Division, carrying copies of the plans for the defense of the capital.123 As pleased as he was to receive this intelligence, only much later, as the day wore on, did von Falkenhayn began to appreciate the growing danger to von Mackensen.

Responding to the OHL’s directive of 28 November to engage the Romanians in the mountains, the LIV Corps had advanced northeast rather than east after crossing the Olt, widening the gap between the two German armies. The Romanian orders revealed that their maneuver group planned to enter this space and attack the left flank of the Danube Army, while the Russian IV Corps coming from the Dobrogea would keep the right flank busy. Von Falkenhayn conceded that the plan was good, except that the Romanians seemed totally unaware of the fact that the LIV Corps was moving across the region between the two armies where they planned to attack von Mackensen.124

The Romanians were aware that Kühne had four divisions in Walachia. What they did not know – and their ignorance was a testament to von Schmettow’s work – was exactly where the German infantry was. It was much closer to von Mackensen than Prezan realized.125

Von Falkenhayn saw an opportunity to turn the tables. If Kühne continued northeast, his divisions would soon be marching between the Romanian 1st Army and Prezan’s maneuver group, cutting the lines of communication to both at one thrust. Von Falkenhayn ordered Kühne to split his corps, sending the 301st and 41st Divisions to the northeast behind the Romanian 1st Division to help the Alpine Corps. He directed the 11th Bavarian and 109th Divisions to march southeast and fall on the rear of the enemy’s divisions, which had begun to engage von Mackensen.126

Closest to the Danube Army was von Kneussl’s 11th Bavarian Division, bivouacked on the west side of the proposed railroad between Rosiori-de-Vede Bucharest (the boundary between the two armies), some twelve miles distant. Without any sense of urgency, von Kneussl called for his division to get under way the next morning (2 December) at 7:30 AM, marching in two columns to the relief of von Mackensen.127

Von Mackensen knew the Romanians had made contact with his divisions, and initially he did not seem too concerned In fact, he said that he did not need the 109th Division, so Kühne redirected it north to follow the 41st Division.128 As reports came in, revealing where his and the enemy units were, the field marshal realized that the enemy had managed to separate the 217th Division from von der Goltz’s. Prezan’s maneuver group had successfully marched fifty miles in two days, fending off von Schmettow’s cavalry,129 driving von der Goltz’s division back southwest to Naipu, and exposing the left flank of the Danube Army. Von Gallwitz, marching his 217th Division toward Mihailesti on the Arges, thought von der Goltz’s riders still protected his flank, with Major Hugo Pflügel’s Jäger battalion between them and his infantry regiments. Von Gallwitz was unaware how close the Romanians were.130

All day long, rumors about masses of enemy soldiers swirled through the columns of the 217th along with the fog. The unit reached Milhailesti just before dusk and quickly established a perimeter. Von Gallwitz knew that von der Goltz had engaged the enemy, but he did not know that the cavalryman had pulled back. Von Gallwitz thus did not realize how isolated he was, although he was painfully aware that his artillery was short of ammunition and his men were tired. Pflügel’s Jägers were in worse shape after several hard engagements.131 At nightfall, the Romanians attacked, taking the Germans by surprise. Colonel Walter Vogel, commander of the 18th Landwehr Brigade, was summoned to a call from division headquarters, but all he could hear were the garbled words, “Romanians … here,” and then the line went dead.

The Romanian attack drove the 217th back from Milhailesti, pushing it southwest six miles to Stalpu, on the Nealjov River. The Jäger Battalion rescued the retreating Germans, holding off an enemy assault just as the division’s artillery crossed the Neajlov. At dawn, Pflügel could account for only 380 men from a complement that had been close to 700. Vogel’s Landwehr had marched last, with the colonel’s staff forming the rear guard, arriving long after midnight. The Romanians claimed to have captured twenty-six cannons and 1,500 soldiers.132 Good leadership had provided a momentary reprieve for the Germans, but the situation was precarious. The division was cut off and the army’s flank exposed.

When von Mackensen and his staff found out that the enemy had separated the 217th Division from the rest of their army, they acted immediately, contacting Kühne’s headquarters, whose staff informed the 11th Division at 3:30 AM on 2 December that the situation was critical. Von Kneussl woke his right column and told its commander to move out immediately through Radulesti to Lecta Veche, the presumed location of the Romanians. At 4 AM, Kühne ordered the entire division to get going. On von Kneussl’s heels came the Württemberg Mountain Battalion. No one, however, could tell them where to expect the enemy.

Von Kneussl solved the problem by marching to the sound of the guns. By 10 AM he heard enough small-arms and artillery fire to steer the division in the fog southeast to Clejani and Mereni, giving directions “to engage the enemy with all means at once and to throw him back. The weight is on the right flank.”133 The Württembergers also attacked, although their chronicle says their artillery did most of the “talking.”134 By afternoon the fighting had died down and the Bavarians had moved into both villages, but they had not seen the 217th Division. They discovered from interrogations that they had engaged the Romanian 9/19th Division. Tired and hungry, the prisoners told their captors that their division had unloaded at Pitesti after coming from the Dobrogea and then had to march back to Bucharest.135

Sensing that matters were slipping out of control, Berthelot frantically tried to speed up the Russian deployment of the IV Corps to the Danube Defense Group. Berthelot and Prezan had given up on Beliaev. Instead, they turned to General Sakharov, commander of the Russian Danube Army in the Dobrogea. For several days they had tried to make him understand how critical it was to get his troops to the front. Units of the 40th Division had arrived at the Budesti rail station southeast of the capital on the 29th, but the division commander, General Rasvoi, refused entreaties to move to the Arges.136 Berthelot persuaded Sakharov to come to Peris, where the king and Bratianu added their pleas. Sakharov was convinced and issued orders to move the 20th Division to Bucharest, and he managed to pry the VIII Corps from Moldavia, where it was stationed as the reserve for Lieutenant General Platon Alekseevich Letchiski’s 9th Army.137 Rasvoi marched his division to the front later in the afternoon, but it did not become decisively engaged, and he retired the next day.138 General Eris Khan Alieff’s IV Corps did not arrive from the northern Dobrogea until after the battle, having had to march on foot the entire way.

The Bavarians resumed their advance at daylight on the 3rd. Marching east in two columns, they hoped to come across the beleaguered 217th Division near the village of Stalpu. Fighting began around 10 AM at Bulbucata, a village next to Stalpu on the Neajlov River, where the 217th was surrounded. The division’s three regiments had an effective strength of 850, 500, and 300 men. All morning the 2/5th Romanian Division had attacked, driving the flanks of the division’s perimeter closer. The end looked near.

The Romanians made a wild charge at noon. Suddenly, in their rear ranks white clouds of shrapnel appeared. Von Kneussl’s division had arrived. Surprised, the Romanians panicked and fled. Their commander, General Alexandru Socec (1859–1928), allegedly mounted his horse and did not stop until he was in Bucharest.139 Many other troops ran into the village of Epuresti. The Bavarian infantry followed them, while artillery fired on the village. Two long columns emerged with white flags. The sight unnerved the 9/19 Division, whose men joined in the gallop to Bucharest. The Bavarians followed, and by 11 AM they had taken the villages of Bulbucata and Facau. The division, with its Württemberg reinforcements, drove the Romanians east toward Mihailesti, where two pontoon bridges crossed the Arges River.

The region between the Neajlov and Arges Rivers, five to seven miles wide, forms a plateau with little cover. Von Kneussl’s artillery punished the terrified Romanians as they retreated across what became a zone of deadly fire. What the cannon shells missed, the rifle and machine-gun bullets found. Few Romanians survived the terrible journey. The pursuing Bavarians entered Milhailesti around 4 PM and captured what was left of the two pontoon bridges. One could be used by foot soldiers; the other was destroyed.140

The Germans, Bulgarians, and Turks spent the next day mopping up, clearing the villages along the west bank of the Arges. The 11th Division rounded up 59 officers (including 4 regiment commanders) and 1,705 soldiers. Kosch informed von Kneussl that afternoon that his division would remain in place while the heavy artillery set up to reduce the forts guarding Bucharest.141 Both German armies reported substantial captures of men and materiel: the 9th Army took 19,000 prisoners; the Danube Army’s tally was reported as 5,000 prisoners and thirty guns.142 The extent of the Romanian defeat revealed itself over the next few days as another 51,000 prisoners, 85 artillery pieces, and 115 machine guns were rounded up. Most of these came from their 1st Army in the north, whose flight to avoid having its line of retreat blocked by the 41st Division was so precipitate and through such inhospitable terrain that the casualties were very high.143

The German 9th Army continued its drive to cut off the retreat of the Romanian 1st Army. The 41st Division had crossed the Arges below Titu on the 2nd, and on the 3rd it took Odobesti, blocking Romanians fleeing from Krafft’s corps coming south along both sides of the Arges. Von Morgen’s men had reached Ungureni without much of a struggle, but the terrible condition of the roads dictated that his corps had to march in one column, slowing its advance. The next day saw the 109th and 7th Cavalry Divisions cross the Arges at Malu Sparta, while the 41st occupied the city of Titu, further blocking the retreat of the Romanian units fleeing from the Alpine Corps. The 12th Bavarian Division entered Targoviste.144

Von Falkenhayn was satisfied. Along the length of the Arges River, from the mountains to the Danube, the two German armies had faced and beaten almost the entire Romanian army. The enemy, he wrote, had overlooked Kühne’s corps, allowing its divisions to divide and turn the internal flanks of each enemy force – the 1st Army and Prezan’s maneuver force – leading to the defeat of both. As von Schmettow recognized, “the speed of our advance had been enormous … artillery and reinforcements could hardly keep up … nevertheless, the word was always ‘forward and destroy the enemy.’”145

In honor of the victory, the kaiser ordered the ringing of church bells in all Germany on 4 December.146 Von Mackensen ordered the 9th Army to pass between Bucharest and the edge of the mountains while he told the soldiers of the Danube Army what they already knew: “The battle cry is Bucharest!”147