Guillermo del Toro is not a tourist, meaning he can’t turn off who he is. There’s no way to fake your way through his kind of authenticity, that kind of passion. He doesn’t study charts that say, “This is the type of movie that will make money,” or go, “Here’s a niche in the market I can fill.” There are plenty of people out there who are also passionate. Most people are either gifted writers, but they’re not visual. Or they’re very visual, but they’re not storytellers. Guillermo is all of those things rolled into one, which is very, very rare. He is equipped with the skills to be able to bring that passion to life. That’s what separates him. —THOMAS TULL

Guillermo del Toro under prosthetic pieces (applied by Lorenza Newton) and contact lenses. He sculpted and molded this makeup in forty-eight hours for the Hora Marcada TV episode “De Ogros,” co-written and directed by Alfonso Cuarón.

DIRECTOR ALFONSO CUARÓN recalls that the genesis of Pan’s Labyrinth went back to the late 1980s and his earliest working relationship with del Toro on a Mexican TV show called Hora Marcada—a science fiction/horror anthology series in the vein of The Twilight Zone. Del Toro had written a script for an episode, “De Ogros,” and brought it to his friend. “He said, ‘At this stage you’re better at directing than me, so why don’t you develop and direct it?’” Cuarón recalls. “So, that is Guillermo’s generosity. And ultimately that is what happened. And of all those shows we did back then, that is the one I remember most fondly. I can also tell you that story is the seed for what he ended up doing with Pan’s Labyrinth.”

“It was the story of a little girl who had an abusive father and she discovers there is an ogre living in the sewers of her city and she ends up escaping into this underworld, leaving her father behind,” del Toro explains. “She preferred the monster rather than the monstrosity of her father. So it’s very closely related to The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth and probably most of my work.”

Del Toro says the films he made prior to Pan’s Labyrinth prepared him, honed his skills, and gave him the experience to overcome adversity. The director’s course as an artist, and his resolve to not compromise his vision for Pan’s Labyrinth, was determined, ironically, by a production that was both a big break and his least-fulfilling professional experience. The critical success and attention for Cronos had won del Toro passage to Hollywood and his first big studio picture, Mimic, but he recalls the experience as “a losing proposition from the get-go.”

The eventual 1997 release stars Mira Sorvino, fresh off her Oscar for Best Supporting Actress in Mighty Aphrodite, as a scientist who accidentally alters the genetic code of cockroaches, causing them to transmute into six-foot creatures that mimic the humans around them. But trouble began on the first day of shooting in Toronto—a hospital set they were shooting in looked too otherworldly for the producers. Where del Toro was going for beauty and emotional resonance, the producers, del Toro recalls, asked “Are you making an art film out of a B-movie bug picture?” It was the first of many battles, with the final film being recut with added scenes shot by another director. (In sweet vindication, del Toro released his “director’s cut” of Mimic in 2011.)1

Del Toro shared his troubles making Mimic during a visit to James Cameron’s home, giving a blow-by-blow account while they stood in the kitchen. “He told me how they fired him in the middle of shooting and had another director come in,” Cameron recalls. “But the cast supported Guillermo and walked off, because who wouldn’t support Guillermo? When you’ve worked with him you know how passionate and singular his vision is. So the cast defied [the producers] and forced them to bring him back.”

Cameron adds a coda to del Toro’s Mimic travails. At a public event, he encountered one of the Mimic producers. The man strode up, offered his hand, and told Cameron he should come work at a company where they “honor and support” filmmakers. “He had his hand out and I hadn’t shaken it yet,” Cameron recounts. “I started to reach out to shake his hand, because that’s your reflex, but I held back. And I said, ‘Well, if your idea of honoring and supporting the filmmaker is to fire them halfway through their film and only hire them back when the cast protests and walks out, like you did with my good friend Guillermo del Toro, then that’s some shit you can keep, my friend.’ And he went berserk. His face just went red and his veins bulged and he transformed into this, like, salivating mad dog. He kind of came after me, and two of his guys had to grab him and pull him back. I was ready to [defend myself]. I bare him no malice, other than the fact that he fucked over one of my friends, and that goes back to the honor thing. Ultimately, I would kind of love to see that alternate universe where I’m in jail today for having taken him out. I told Guillermo about it, and he laughed for days.”

Del Toro with friend and fellow filmmaker James Cameron at the Los Angeles premiere of Hellboy in 2004.

Image of Guillermo del Toro and James Cameron courtesy of Featureflash Photo Agency/Shutterstock.com.

The worst of Mimic came when del Toro got news that his father had been kidnapped and was being held for ransom in Mexico. The problems of making a film instantly paled. Del Toro recalled his reaction to the crisis in Christlike terms—after all, he was thirty-three years old: “The perfect age to be crucified!” he told a reporter. “Having gone through that experience, I can attest, in a non-masochistic way, that pain is a great teacher.”2

Cameron came to the rescue and provided his friend with the fees to pay a negotiator from the UK to handle the first part of the kidnapping. The del Toro family would ultimately pay the actual ransom. After some seventy-two days, the unhurt and healthy Federico del Toro was freed. Although the senior del Toro opted to stay in Mexico, his son decided to move his family—wife, Lorenza Newton, and daughter, Mariana (a second daughter, Marisa, would be born after The Devil’s Backbone was shot)—out of his native land and to the US, settling in Austin, Texas, first, before moving to Ventura County, near Los Angeles.

A bright spot in that traumatic period was that on Mimic del Toro met Doug Jones for the first time. The future Faun of Pan’s Labyrinth never planned a career playing fantastical creatures requiring elaborate makeup and costumes, but his rare physical talents seemingly made it inevitable. “When you arrive in Hollywood and you’re six feet, three inches, weighing 140 pounds, with a background in mime—and my one party trick is I can put my legs behind my head—well, that makes you rather appealing to the people who make creature things,” Jones explains. “I’m on the Rolodexes of all the creature shops who need a tall, skinny guy to fit [makeup or costume characters].”

Jones was on Mimic for three days’ work performing as one of the cockroach-like creatures, but he didn’t meet the director until the second day, when they sat across from each other at lunch. Del Toro gave him a contemplative stare and asked, “So, tell me everything you’ve been in before.” Jones listed his credits, and del Toro was familiar with each one and had insightful comments, particular regarding the creature and makeup effects. “I was so taken with this man, how affable and kind he was—and what a squealing fanboy!” Jones says. “It was like the conversations I’ve had with fans at conventions. That’s when I knew this one was different—this one was a keeper.”

In 1998, a year after the release of Mimic, del Toro and a team of Mexican filmmakers that included Bertha Navarro formed a production company with a two-fisted name, Tequila Gang. In a Variety article it was reported that Tequila Gang was already a presence at the Toronto Film Festival, negotiating projects that included del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone, a projected seven-million-dollar production to be shot in Spain.3

Rather than crushing del Toro’s spirit, Mimic had clearly strengthened his resolve to fight for his creative visions and partner with like-minded artists to make sure his work would not be interfered with in the future. “What it did was convince me that from that moment on the only thing I would defend was the right to do things as I see them,” he explains. “I have, since Mimic, not made a single movie where I felt I was creatively compromised. I may screw up. I am not infallible. But as I’ve said repeatedly, ‘Success is fucking up on your own terms.’ And in that regard I think I’m successful!”

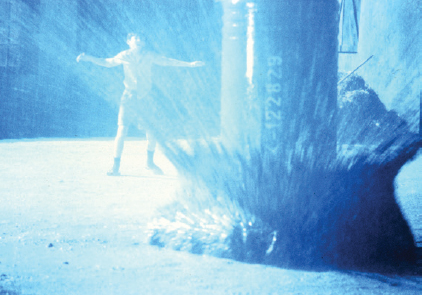

The ghost boy, Santi (Junio Valverde), in The Devil's Backbone. Pan's Labyrinth would be the second in a projected thematic trilogy set during the era of the Spanish Civil War.

It was natural that after the debacle of Mimic the writer/director wanted a break from the Hollywood system. James Cameron reflects, “I’ve gotten to know Cirque du Soleil quite well and how that culture works. They make their money chasing ideas that are so surreal, dreamlike, and whimsical that they sometimes can’t be quantified on paper. So they look for the most creative people and trust and support them. That’s the culture that Hollywood should have but doesn’t. You throw a guy like Guillermo del Toro into that culture and he’s bashing his head against the walls and sometimes he gets so tired and bloody that he goes off to make what he calls his ‘little Spanish-language films.’ The second time he did that he came back with The Devil’s Backbone. All of his films are amazing, but that one is a jewel.”

Originally, del Toro envisioned his ghost story set against the backdrop of the Mexican Revolution but later realized it would be clearer if the setting were the Spanish Civil War. “The Mexican Revolution started with an uprising, and then a coup, and was a war between factions, with constant betrayals and changes of power,” Alfonso Cuarón explains. “There was less ambiguity with the Spanish Civil War. In Spain it was pretty much a very unified right wing fighting a very fragmented left. And both The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth are set in the final part of the war, in which the fortune goes with Franco and the right wing. And you can see the monsters that start to come out of that, all those ghosts that Spain has been unable to hide.”

The Devil’s Backbone would become a kind of training ground for Pan’s Labyrinth, providing a number of filmmaking lessons, not least of all those learned from plotting its stunning cinematography. Guillermo Navarro describes his work with del Toro on Cronos as “a beginning,” but on The Devil’s Backbone they established a true creative partnership—together they would develop del Toro’s philosophy of storytelling without words. Del Toro talks about “visual rhymes,” imagery that echoes throughout a story, and even from movie-to-movie; he distinguishes flashy eye candy visuals from what he calls “eye protein,” in which visual elements—their color palette, even shapes and textures—help tell the story. With this philosophy in mind, the camerawork that del Toro and Navarro developed on The Devil’s Backbone formed the visual language they would bring to the labyrinth.

The ghost boy, Santi (Junio Valverde), in The Devil's Backbone. Pan's Labyrinth would be the second in a projected thematic trilogy set during the era of the Spanish Civil War.

“I think one of the things that makes it hard for actors to work on a movie set with me is that I want them to be dancing with the camera,” del Toro says. “They need to move in a certain way, very precise, and the camera is going to always be moving, as I say, ‘like a curious child, always looking for a better angle, like trying to look over your shoulder to see what you’re doing.’ Guillermo Navarro always finds a way to service those moves quickly.”

“It’s not that Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth are specifically connected in terms of things like color, it’s not that,” Navarro elaborates. “The connection, in all the work I’ve done with del Toro, is that the film language is a visual narrative. The way the scenes are shot and blocked, they become elaborate ballets of the camera, which is a very technically complicated thing to do.”

To achieve that balletic effect, the major cinematographic tools included a Steadicam and a small crane they discovered in Spain that would become part of Navarro’s arsenal in Pan’s Labyrinth and beyond. “On Devil’s Backbone we had this extraordinary crane operator named Carlos Miguel, a genius, who was part of the design of this crane,” Navarro says. “Now they actually manufacture it, but at one point this was built in someone’s garage. This little crane allowed us to move the camera in a very solid but elaborate way and only needed one person to operate it, which reduces the problems with the typical crane where more people have to be involved in the motion. Although we were all speaking Spanish on set, we used English for film terms, like ‘push in.’ The way Carlos pronounced it sounded like ‘puchi,’ so that’s what we called it. The Puchi crane.”

Following the September 11 attacks and del Toro’s decision to continue the themes of The Devil’s Backbone in a trilogy of films, it became clear that the next film in the sequence, Pan’s Labyrinth, would be a mirror image of its predecessor. In both stories, an innocent child is driven to a foreboding new home (the orphanage in The Devil’s Backbone; the mill in Pan’s Labyrinth), the supernatural manifests itself the first day in daylight and nighttime, and reality and fantasy intertwine. There is also evolution between the two films’ villains as Jacinto (played by Eduardo Noriega), the adult orphan in Devil’s Backbone, represents a crude “proto-fascist,” as del Toro calls him, while Captain Vidal is a full-fledged one.

Del Toro would make his story a conscious melding of fantasy and reality. “I thought of how some people feel that fantasy is an escape from reality, a notion that I find condescending and incredibly irritating,” he says. “Fantasy is a language that allows us to explain, interpret, and reappropriate reality. It is not an escape and I’m very vehement about that.” Although he had strong feelings about the core themes of the film, he recalls his initial writing stage as a freewheeling period in which he simply let his imagination roam: “I go through a bunch of permutations where I write crazy stuff I can’t afford and then I go back to my original notes.”

With fairy-tale lore as a touchstone, del Toro recalled classics stories of princesses who are frustrated by the constraints imposed upon them by their rigid fathers and each night escape into a fairy-tale kingdom where they dance until dawn, returning exhausted and with their shoes worn out. That led to the idea of a woman who escapes her Fascist husband by entering a fairy-tale world where she meets a beautiful Faun who, it is revealed, seeks to offer her baby as a sacrifice that will make the dying plants in a labyrinth bloom again. But that idea took another turn as the Dickensian tradition of an orphaned child, an Oliver Twist or Nicholas Nickleby, tugged at del Toro’s imagination. But the idea of a boy clashing with his father was not the story he wanted to tell.

Cinematographer Guillermo Navarro. Although Navarro served as DP on del Toro’s Cronos debut, their creative bond was truly forged on The Devil’s Backbone.

A The Devil’s Backbone–themed page from del Toro’s personal notebooks imagines the bomb that hits the orphanage grounds but miraculously doesn’t detonate.

The bomb hit as realized in the final film.

“I knew from the beginning that I wanted it to be a masculine/feminine conflict, because fascism is masculine, and I very much wanted it to be about the strength of a woman against the brute force of a man,” del Toro explains. “I understood, through my daughters, there would be great beauty in making it a story of this quintessential girl in the rite-of-passage moment in which she is told to grow up and behave like a lady, to stop thinking of childish things, to leave the toys and fairy tales behind. I understood the character of my daughters, who are very strong in fighting for who they are in the real world against the silliness that we give them as parents. They have a better idea of where they want to go, in many ways, than the adults around them.”

Through this process, del Toro came up with the narrative structure that helped unlock the story: “One of the constant things in fairy-tale lore, no matter where—Japanese, Javanese, Chinese, Indonesian, European, American—is that the rule of threes seems engrained in the storytelling, you know? It’s three bears, three brothers, three wishes, three doors, three tasks. So I decided that I would construct the story in threes. There are the three tasks Ofelia faces, the three women who represent three possible futures [Ofelia, Carmen, and Mercedes, Vidal’s housekeeper]. There are three main bad guys, the two lieutenants and the Captain. The movie is full of the rule of threes.”

Even before a screenplay was finished, he had the full story in his head. As del Toro laid the groundwork for the production, he consulted with one of his valued peers. “Over lunch he told me the whole story, beginning to end,” James Cameron recalls. “It was like a fairy tale, and just by the way he told it, it was clear how magical and wondrous it would be. I eventually read the script and we had a more detailed discussion.”

As the second of del Toro’s filmmaking forays in Spain, Pan’s Labyrinth was again to be a communion of two cultures whose relationship was very old and very complex. “Spain has a strong influence in Mexico, definitely, but we mark the difference, you know?” says Bertha Navarro. “We are not Spanish—we are Mexican! And there is this hate/love thing. The conquest of Mexico by Spain was severe. They destroyed everything. And we did incur the racism toward the indigenous people. So that culture is lying underneath, and also within yourself.”

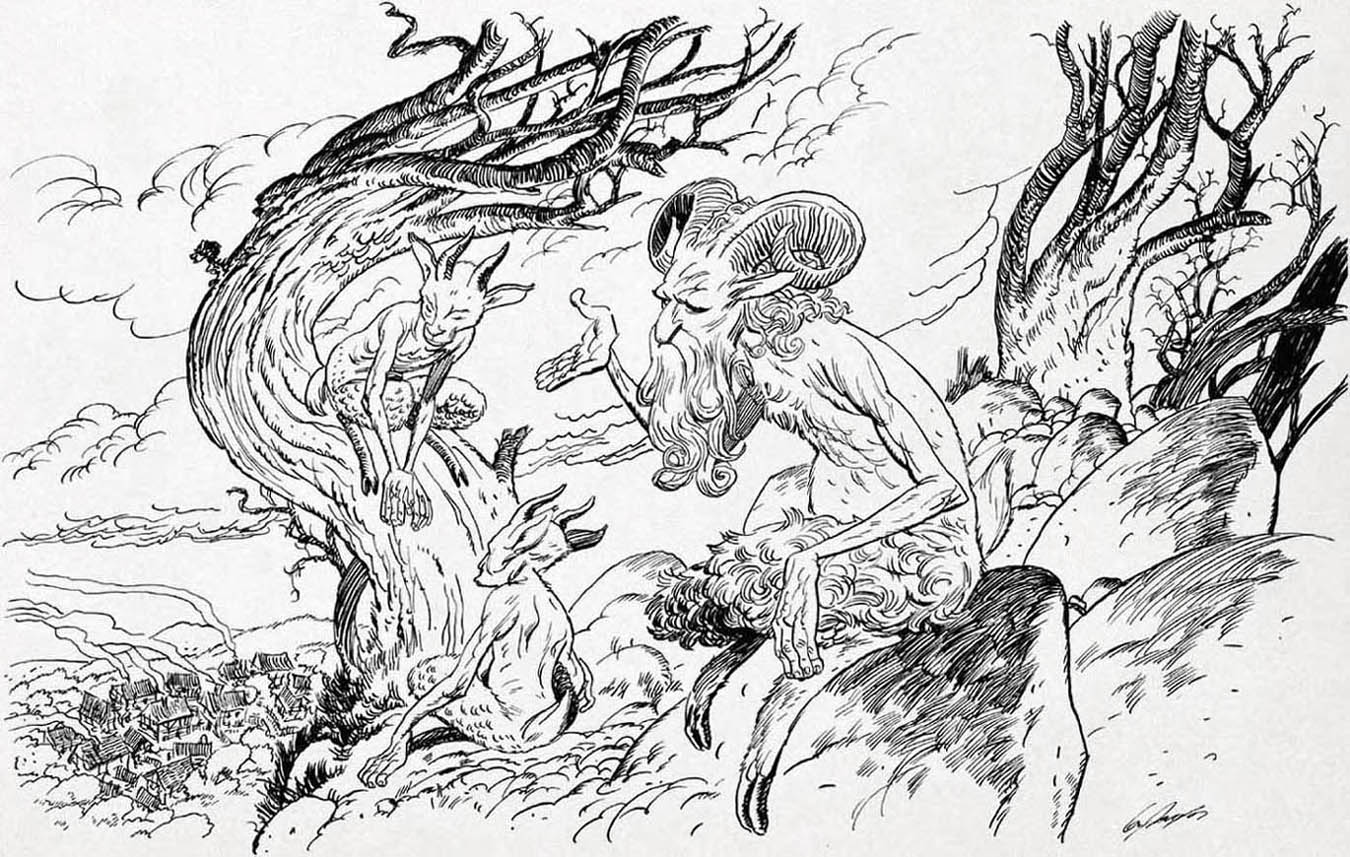

Fairy-tale themed artwork created by Guy Davis for the Pan’s Labyrinth DVD release.