The movie takes you through a world that is completely in the mind of the girl. The biggest challenge in terms of film language was being able to walk [into the fantasy world] from the reality of a historic time within the world of the military group where the girl lives. We had to create symbols and a process to allow the girl to be the thread that puts all this together for the audience. We had to do what we called bridges, going from one world to the other. Everything had to be created; we had to build sets. We decided the movie was full of risks and we had to do it in a very risky way. —GUILLERMO NAVARRO

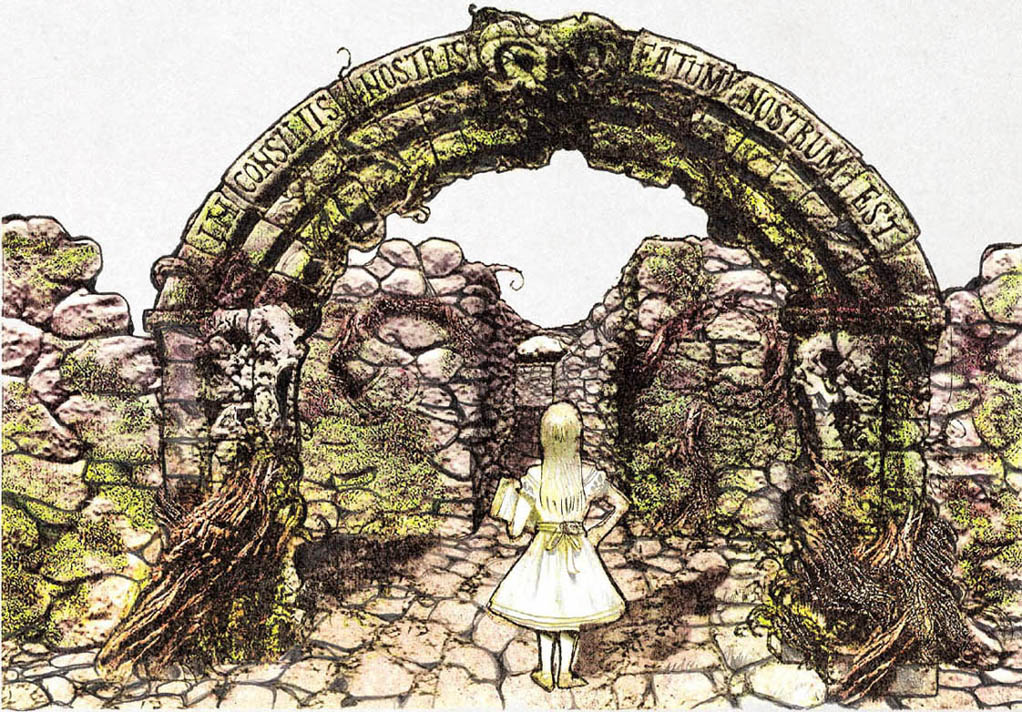

Concept art by Raúl Monge imagines Ofelia as Lewis Carroll’s Alice on the threshold of the labyrinth and its realms of wonders.

A LABYRINTH is a place and a state of mind, from patterns drawn upon cathedral floors to standing structures built by ancient cultures. With a labyrinth as the film’s central image, the production design team researched the types and looks of labyrinths, from their use in Celtic culture to the trim vegetative walls of elaborate garden mazes, before deciding on an ancient place of stone.

All the sets would develop from conceptual design to final builds, and del Toro began the process by personally selecting a team of conceptual artists, starting with Carlos Giménez. “A small group of us, we started designing even before Eugenio showed up so that he would land on a sort of concept track and be surrounded and supported by a really strong crew,” del Toro explains.

The art department was set up in Madrid, in a space surrounding del Toro’s own office. “It was beautiful because Guillermo’s office was in the middle of the art department,” Eugenio Caballero recalls. “So we had a lot of access to each other.”

In the five months prior to receiving the screenplay, Caballero’s research had delved deep into the tale’s fascistic atmosphere—along with studying the Franco era he had even visited the concentration camps at Birkenau and Auschwitz that bear witness to the Nazi’s machinery of genocide. Much like del Toro pours his ideas into his famous notebooks, Caballero creates production design books and had filled his Pan’s Labyrinth book with inspirational and reference imagery; included were period photographs of the Civil War, images of northern Spain, genocidal conflicts from the Balkans to Africa, and reproductions of the fantasy artwork of Arthur Rackham and other Victorian-era illustrators.

Labyrinth arch detail, concept art by Raúl Monge.

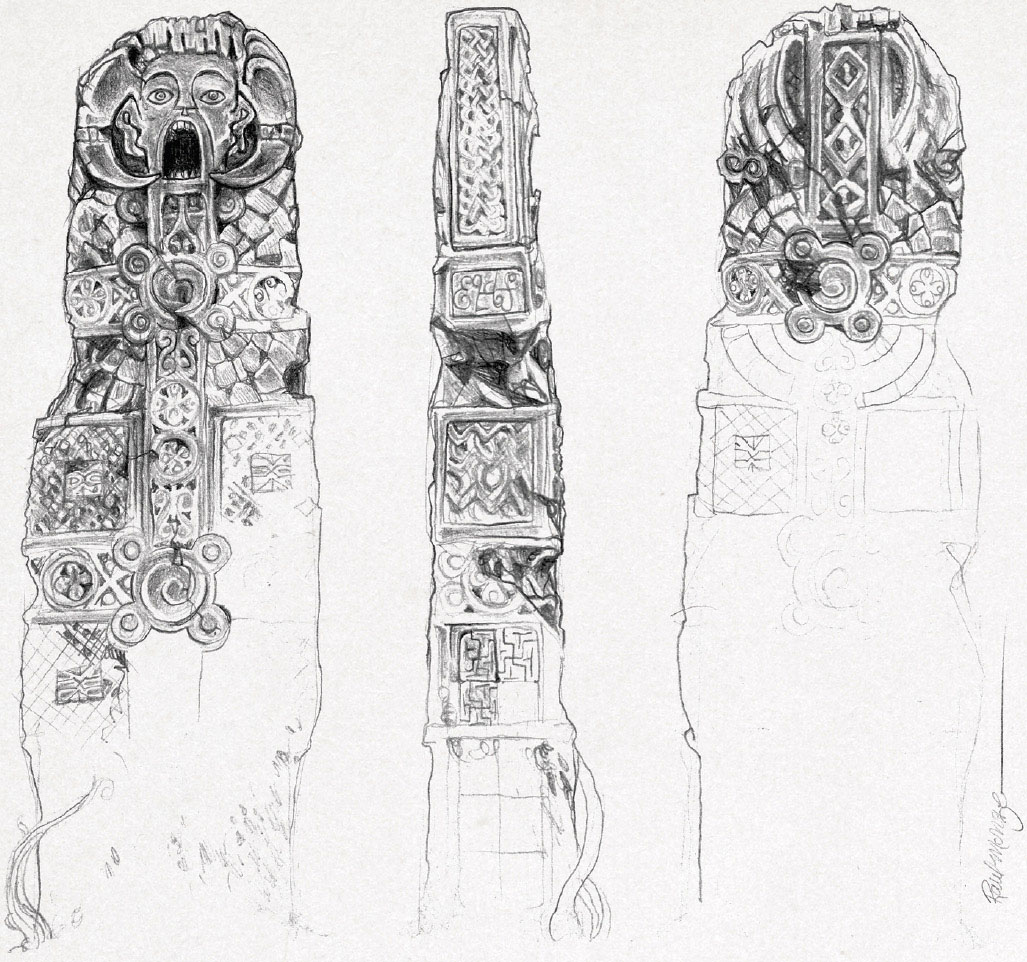

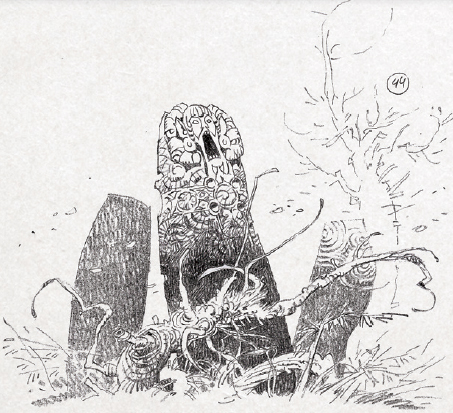

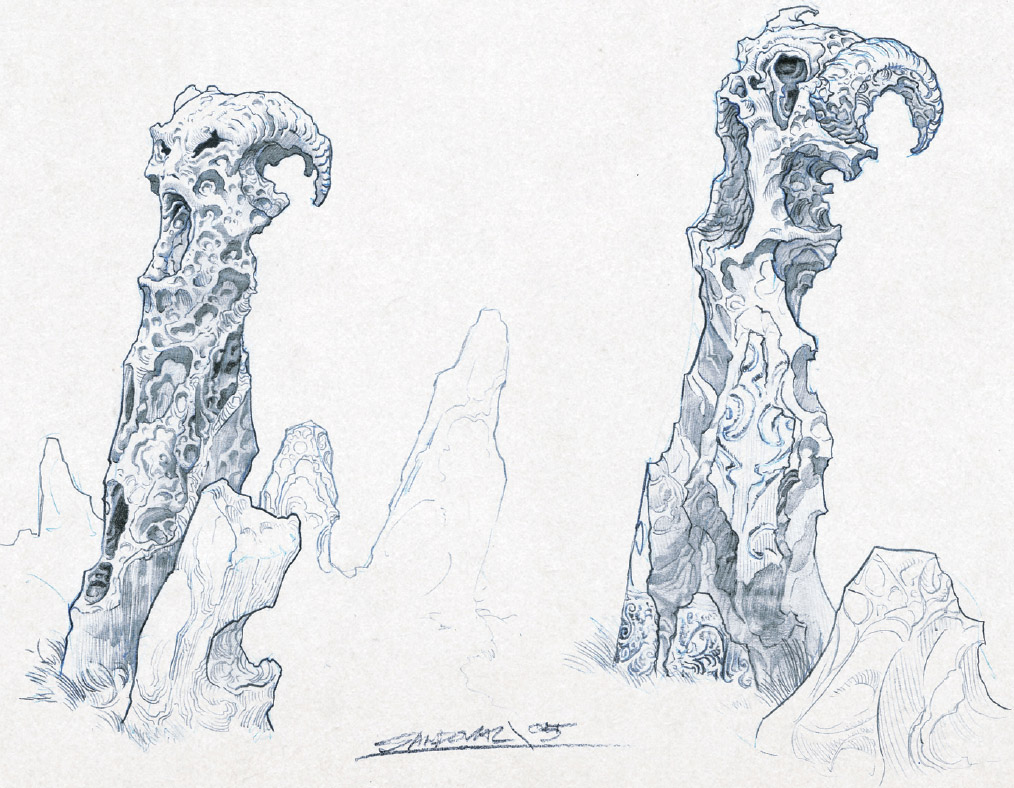

Conceptual art by Raúl Monge of the monument Ofelia discovers during the drive to the mill.

Final construction for the stone monuments.

Another interpretation of the monument, this time by Carlos Giménez.

Entryway into the labyrinth, final set piece.

Concept art by Raúl Monge for the stele at the bottom of the labyrinth, with carved imagery of the Faun and a girl holding an infant, foreshadows Ofelia’s protective role with her infant brother-to-be and her final task.

Steps leading to the bottom of the labyrinth and the symbolic stele, concept art by Raúl Monge.

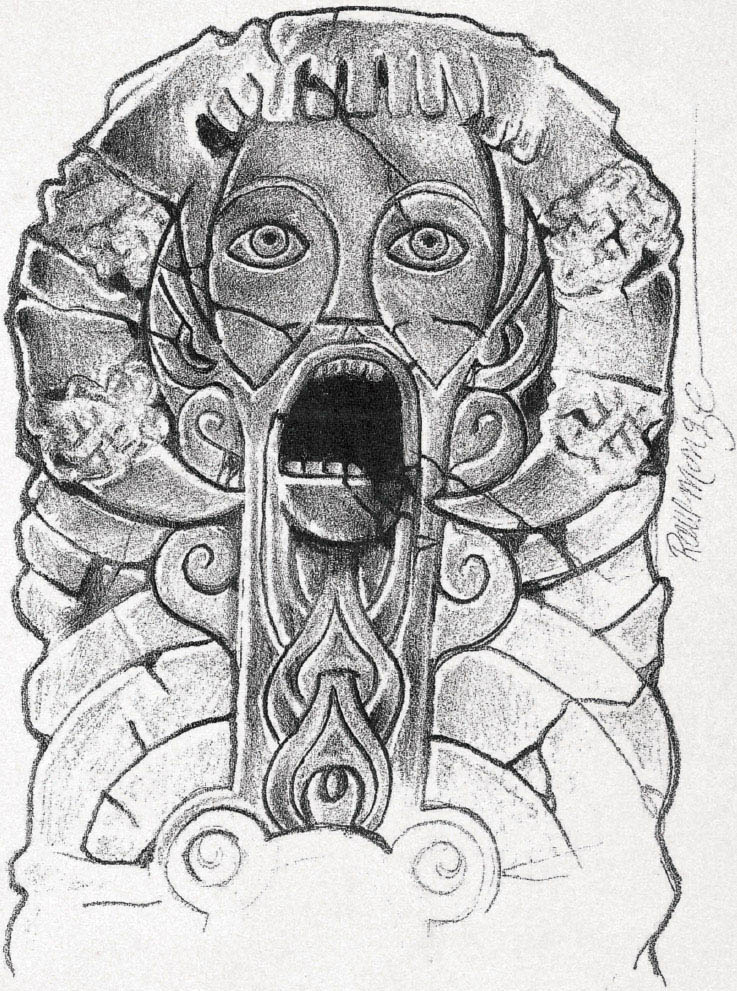

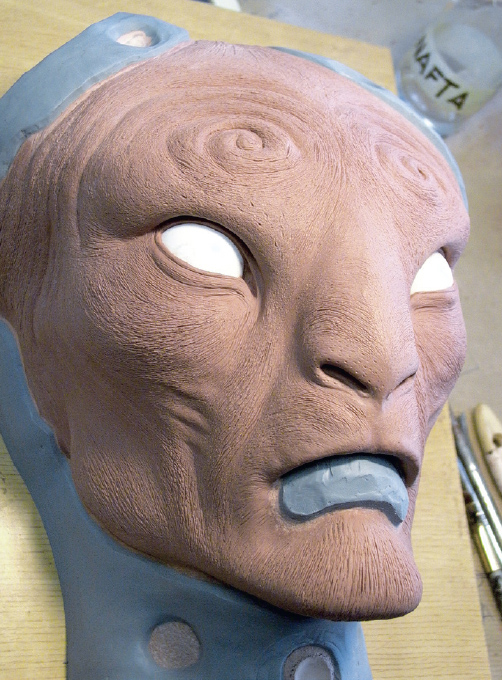

Stone monument face, concept art by Raúl Monge.

“When Guillermo came back with the script, I presented this book to him,” Caballero says. “It was, I think, the moment he felt we were aiming toward the same goal. [Doing reference books] was already my process for many films. The creative thing about making a film is the opportunity to speak in a new way. My books are a tool and a good reference, and reflect for me the feeling of the film. The [Pan’s Labyrinth] book itself was like an antique notebook numbered with ink stamps. The documents I saw from the Franco era, when they wanted to control everything, inspired me, and that style is reflected in the book. It was a beautiful and useful tool for exploring ideas with the director or a producer, director of photography, and all the people who work with you in the art department.”

In del Toro’s story, the three tasks that Ofelia had to perform would take her into fantastical realms. To del Toro, it was important that there be a clear division between the worlds of reality and fantasy. There would be “eye protein” rules separating each, but they would also be connected—Caballero recalls that was del Toro’s first ground rule. “In a certain way, there was a mirror between both worlds and the question was always how to play with this idea in a cinematic and poetic way, without being too obvious,” Caballero notes. “The other things we knew were that the world of fantasy had to be warmer than the real world, that there was this big contrast between them. Those were the first two ideas.”

On location, construction on the labyrinth steps begins.

Sergio Sandoval’s take on the monument involves a ram’s head design that evokes the Faun.

“There was a lot of discussion of the script and the input of production design, pulling together the things that would deal with the parallel realities,” adds Guillermo Navarro. “In the beginning of the movie the girl discovers a little piece of the stone eye and puts it into that sculpture, the insect comes out, and she relates to it. You’re already in a fairy land, in a world where anything can happen.”

For set decorator Pilar Revuelta, a veteran of The Devil’s Backbone, her process on a movie begins with the script and understanding the story “organically.” From there she embarks on many meetings with the director and production designer to nail down the look of the world. “You talk about their total vision for the project, the textures and style,” Revuelta explains. “With Guillermo it’s easy, because he gives you a ton of information. Guillermo will have his little notebook, where he writes in red ink. At meetings he would draw elements of the story, things he already understood visually. What’s funny is he would write upside down so we could see from where we were sitting.

A grim Vidal (top), menacing Pale Man (middle), and a resplendent Ofelia in the underworld kingdom (bottom). Each image speaks to the film’s color palette—cold hues for the real world, warm colors for fantasy realms, and glorious gold and red for the mythical kingdom.

My contribution starts with photos and references that I show the production designer for things like furniture, things that will contribute to the style of the film. In Pan’s Labyrinth, for example, we did color swatches. The film has three major journeys, so we wanted three different hues.”

The first journey is Ofelia’s troubled reality, the world of Vidal’s garrisoned mill, so blues and other cold colors were dominant. The second journey is the fantasy realms, where warm colors rule (such as the glow from the chimney in the otherwise terrifying Pale Man’s lair). The culmination is a third, and final, journey—the vision of the underworld kingdom. “In the kingdom, reds and golds appear,” Revuelta says. “These are the things we discussed early on, so that the film felt whole and that the acting, set decoration, the lighting, and wardrobe all moved in the same direction.”

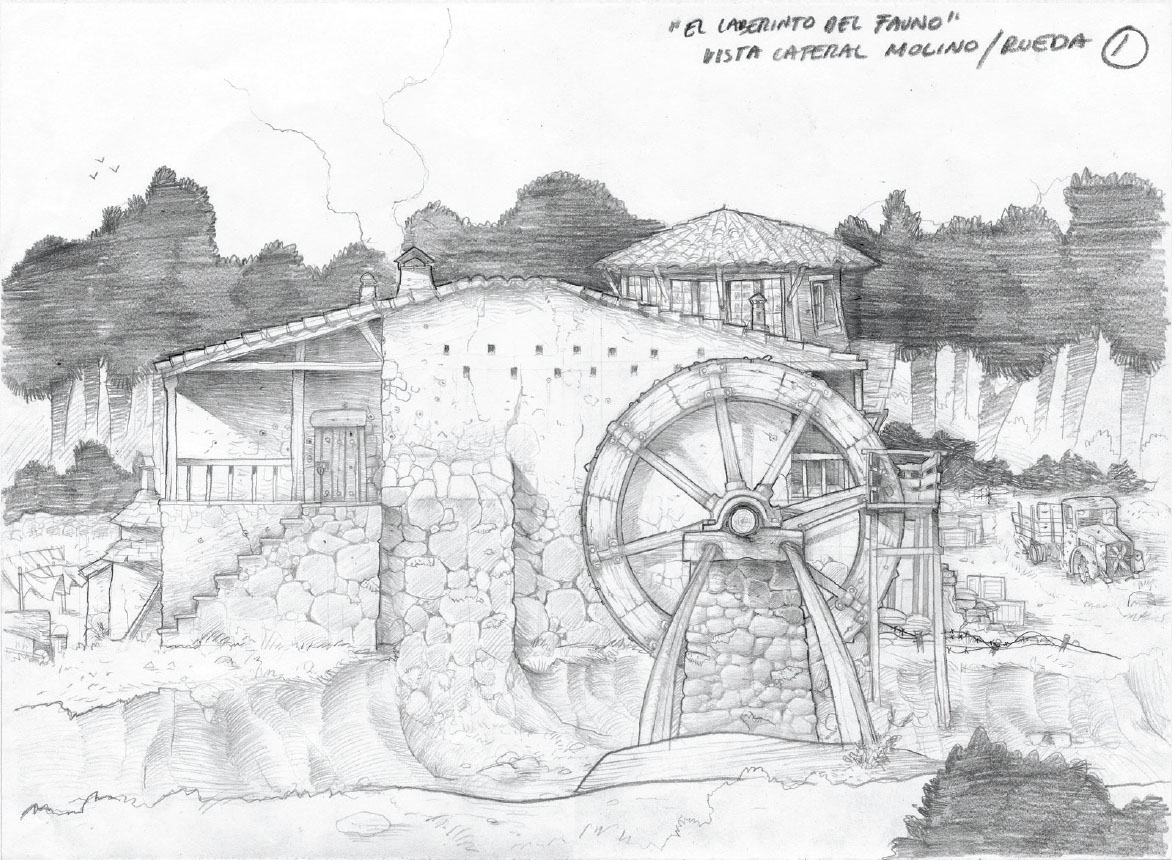

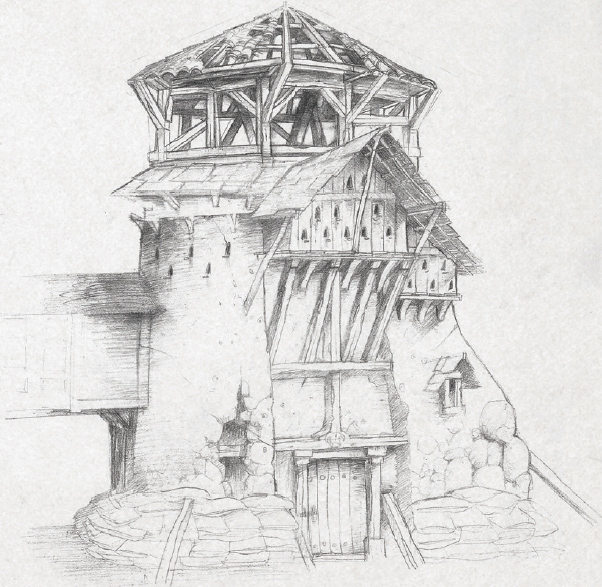

Concept sketch by Raúl Villares of the old mill where Vidal leads his military operations against the rebels.

The design and building of sets on location and the soundstage moved forward under physical guidelines that would give sharp contrast to the worlds. The real world had to look plain but also harsh, with straight lines and angles. The fantasy world was organic and curved, with ornate and detailed environments. But the parallel worlds, in Ofelia’s mind, would also affect and reflect each other.

A craftsman at work on the miniature set of the underworld kingdom.

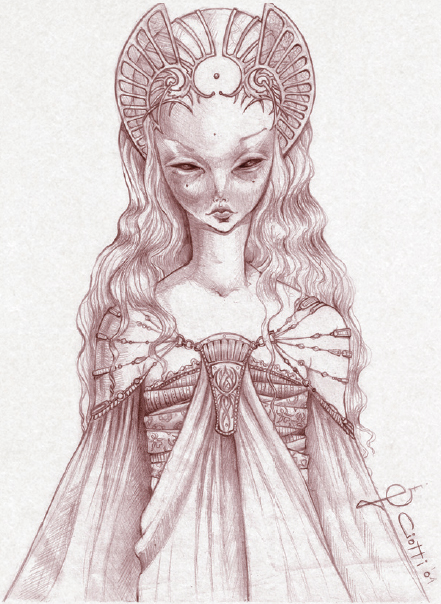

Conceptual art of Princess Moanna by Giorgina Ciotti.

“I think of the fantasy world as what happens below, because Ofelia enters by going down into the labyrinth, and she also goes down into a tree,” Revuelta says. “The fantasy world is made up of circles, spheres, and I think that conveys descent. Things in the fantasy world are fragile and they’ll break on you. But the fantasy world, at its core, is like a rough tracing of the world above. It’s just as dangerous and full of pain. But I think the fantastic world helps this little girl understand what’s happening around her in the real world. In the end, it’s the other side of the same coin.”

The iconography included shared elements between worlds. Keys figure prominently, for example—in the real world, a key locks away the storehouse of valuable food and medical supplies; in the fantasy world, a key is integral to two of Ofelia’s tasks. There would be echoes and funhouse mirror reflections between worlds, with Captain Vidal emerging as the scariest monster of all. As the story unfolded, both worlds would begin to bleed into each other, intertwine, and meld.

The location sets featuring the mill and its attendant structures, along with the nearby labyrinth, were originally planned for northern Spain. “Forests in the north of Spain tend to be more fantasy-like, the shapes of trees a bit curved and sculptural,” Caballero explains. “But we knew the forest belonged to the real world and one of our rules for the real world was that it had straight lines and angles. So we found this beautiful location, a pine forest, near Madrid. Pine trees are extremely straight, almost like spikes or jail bars. Even though that forest was not our first instinct, I think it was one of the most interesting decisions we made in terms of locations, because the forest is like a jail for this girl.”

The script, however, referred to trees heavy with green moss, which pine trees do not have. The art department’s solution was to create it. And so, during filming the “moss squad” would head into the forest to dress the trees with a mixture of sawdust and pigments—“breaking nature’s rules,” Caballero says.

They had to break a lot of nature’s rules in the forest—the location had dry and drought-like conditions. “We had the moss squad, but we also had to add a lot of ferns and plants, almost like set pieces in nature,” Guillermo Navarro notes.

When they learned about the arid conditions at the forested location—the dead grass was “completely golden crisp,” del Toro recalls—the production had to design a complex irrigation system in a half-square-mile radius around the mill. “We planted grass, we watered the ferns and planted new ferns, we started greening the trees with this biodegradable [moss],” he explains.

Study for underground kingdom mural by Sergio Sandoval.

Conceptual art of Princess Moanna by Giorgina Ciotti.

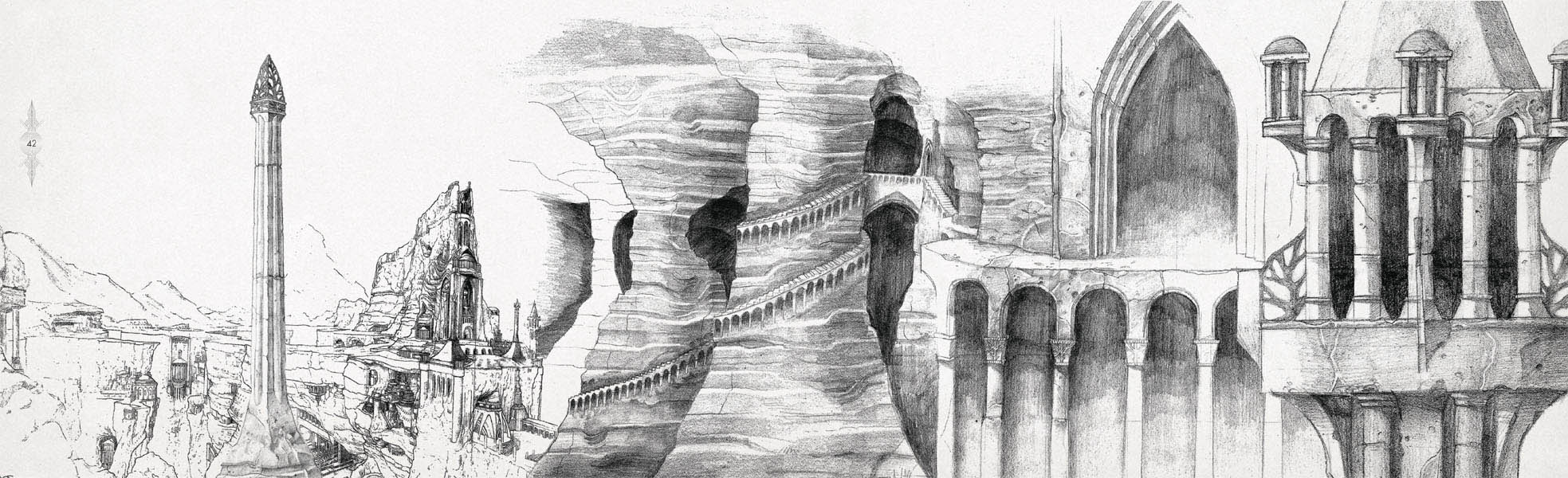

Conceptual art by Sergio Sandoval and Raúl Villares of the underworld kingdom that Princess Moanna leaves behind when she escapes to the surface world.

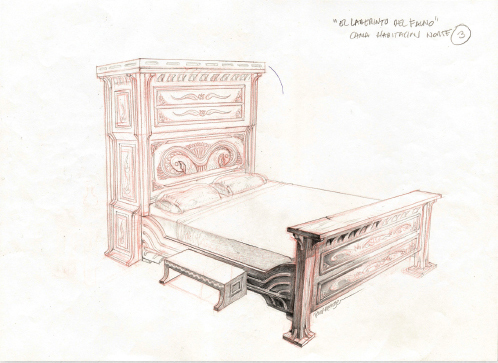

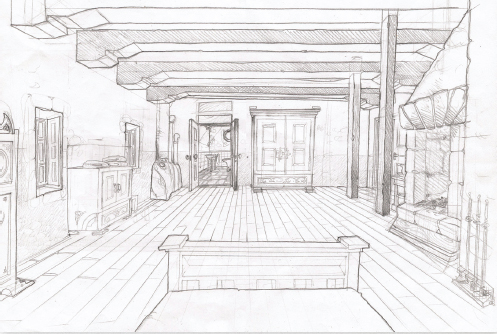

The mill bedroom where Carmen and Ofelia spend their first night, conceptual art by Raúl Monge. The design conveys the austere and oppressive atmosphere of Vidal’s command post.

Concept art for Carmen and Ofelia’s bedroom and bed by Raúl Monge.

Two months before filming began, the dry conditions resulted in a massive forest fire in Spain’s province of Guadalajara (spelled the same as del Toro’s hometown in Mexico) that presented the production with an unexpected problem. “Because of this huge forest fire, the [government agency that was in charge of the forests] dictated that no explosives, fires, matches, or any ignited things could be done in their forests for at least a few years—and we were a war movie!” del Toro laments. “So we were unable to fire blanks for the pistols or create explosions.” This meant the production had to find an ingenious solution for simulating the battles between Captain Vidal’s Fascists and the Republican guerrillas.

The sets evolved from conceptual designs to final blueprints and technical specs that would allow Moya Construction, a Spanish firm, to build the final sets for filming. The mill and other major location sets had always been planned by del Toro to be fully functioning, so that the camera could follow, without cut, the characters as they moved from indoors to outdoors. The mill and labyrinth were also planned to be close enough in proximity that Ofelia would be able to quickly and easily move between them. Fortunately, the chosen location near Madrid allowed for space between the two sets, while keeping both in sight of each other, visually aligning the portals into both worlds.

Conceptual art of labyrinth entry to the portal by Raúl Monge.

Constructed at San Rafael in the Guadarrama Mountains, both sets, particularly the eerie labyrinth, made an impression on the crew. “It was strange at the labyrinth, especially being by yourself,” says CafeFX’s Everett Burrell. “It was impossible to get lost because it wasn’t that elaborate. But it was weird. There is one wall they didn’t put up for a while so you could have easy access to it, but once they sealed it up you had to go through it to get to the center.”

The labyrinth represented the threshold into the fantastical realm and a portal for Ofelia’s potential return to the underworld kingdom. The location set included the old rock walls and steps circling down, with a soundstage set in Madrid continuing the steps down to the open area featuring a centerpiece sculpted stone pillar with carved rings radiating outward.

Labyrinth portal set under construction.

“We had to flatten the area at the location where the labyrinth was going to be, which also needed to be supervised by the [Spanish government’s] forest department, because we couldn’t cut any trees,” del Toro adds. “As a result, there are trees coming out of the walls of the labyrinth. But I thought that was good, it gave the labyrinth a better look, and we started repeating that element in the more [soundstage] set-oriented areas of the labyrinth. And then we needed to do the core of the labyrinth, and that needed to be excavated because you needed to see Ofelia going down into the pit. The logistics of this construction were multiple and complex, so it was really challenging for the production designer, Eugenio. The good news is that Eugenio landed in the hands of Moya Construction, which in my opinion is the best set construction company in Spain and one of the best in the world. Moya was supporting but also very demanding of Eugenio. And I think Eugenio really rose to the occasion and got beautiful sets in return.”

Interior soundstage spaces included Ofelia’s bedroom and bathroom, the Captain’s quarters, the mill’s kitchen and dining room, the Pale Man’s lair, and the throne room of the fairy-tale kingdom. It was a fairly short preproduction period, Caballero recalls, and a rush to build and film. “We had a lot of sets in a short period of time and a limited amount of soundstage space to build in,” he says.

Artwork of the labyrinth steps leading down to the portal and stele by Raúl Monge and Raúl Villares.

Vidal’s quarters, conceptual art by Raúl Monge. The Captain’s sanctum was designed to be utilitarian and reflect the orderly logic of military culture.

William Stout art depicting an early idea for the mill’s design.

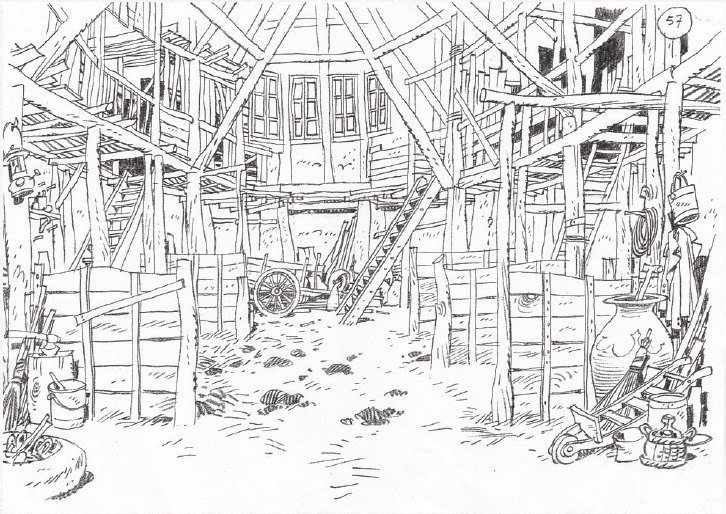

Concept art of a barn at the mill by Raúl Monge.

“We simply had no money, so we needed to maximize the stages and be smart about it because sometimes the sets changed over very quickly,” del Toro adds.

CafeFX digitally extended a number of key sets, with greenscreen incorporated into the practical labyrinth core to provide the illusion of a stairway circling to the bottom portal, while the underworld throne room was realized with a few set pieces (notably the floor and the base of three thrones) on a largely greenscreen stage. Otherwise, Pan’s Labyrinth was mainly a built and tactile world, both in terms of its real and fantasy realms. “The big stone house and labyrinth, among other locations, were built from scratch, so shooting in them made it definitely easier to understand the mood and slip into its world,” Ivana Baquero says. “The level of accuracy and detail on all the sets made it great to work in them. The sets, creatures, and every single element were carefully crafted works of art!”

“You would arrive to the set and be entranced,” says Sergi López. “Everything was there to help you. Say you’re playing Vidal and all you have to do is shave. But you see the set and everything is in your favor—you’re not alone. I come from the theater, where there can be empty spaces and you have to imagine. But it was easy to draw inspiration from the places Guillermo put us. They gave the impression you were a character in a dream.”

The production design and sets were created in tandem with the costume department headed by the award-winning Spanish costume designer Lala Huete. Del Toro hails her as “one of the unsung heroes of the movie,” not only because of the incredibly detailed period wardrobe Huete’s department created, but the circumstances under which she worked. “She had a huge loss in her family and she never, ever brought it up as a pretext to not deliver,” del Toro says.

Del Toro and López discuss a shot on the set of Vidal’s private quarters.

Vidal’s quarters, conceptual art by Raúl Monge. The Captain’s sanctum was designed to be utilitarian and reflect the orderly logic of military culture.

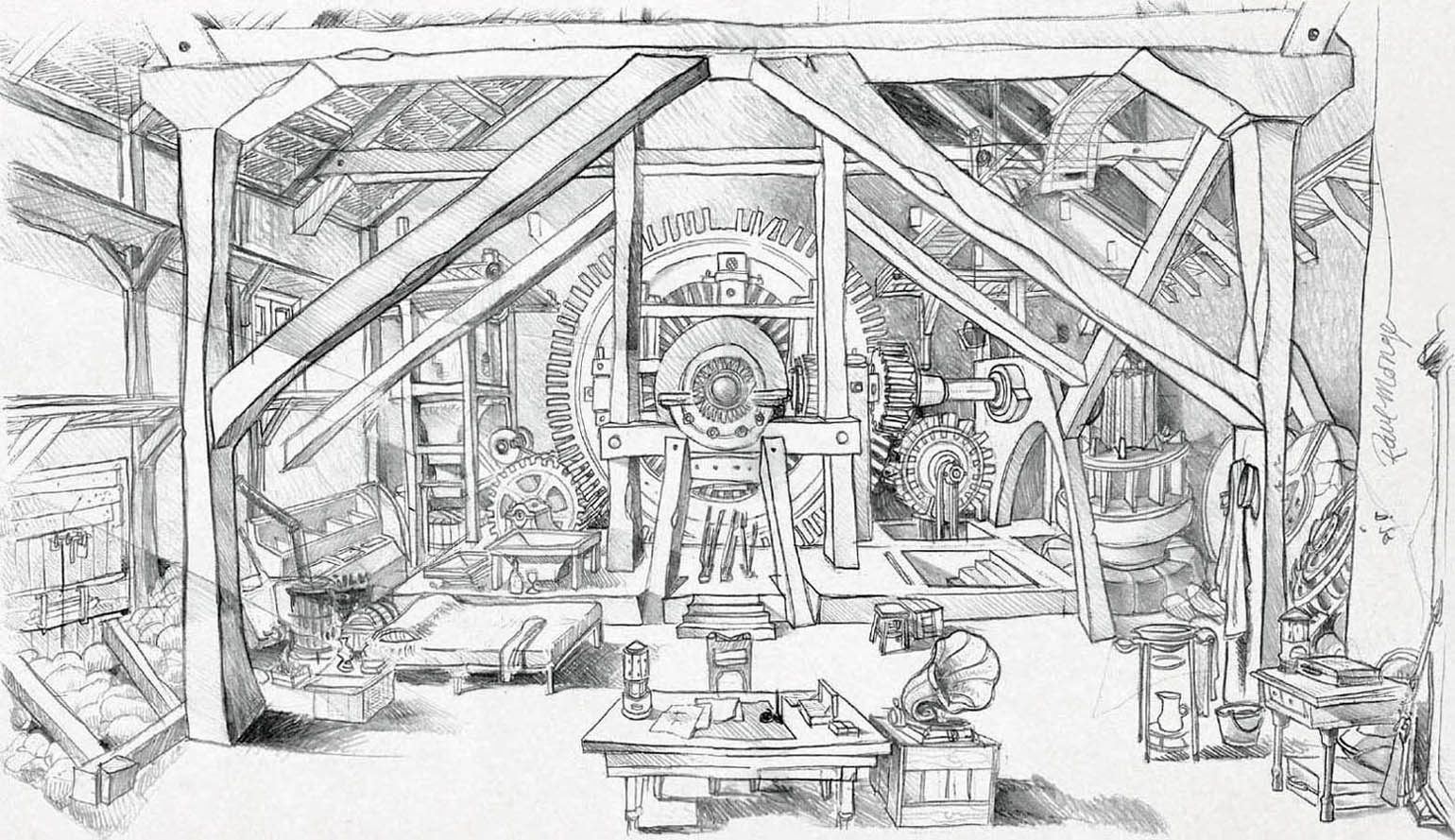

Conceptual overview of the mill by Raùl Villares.

Mill set under construction.

Mill concept art by Carlos Giménez.

Mill concept art with water wheel by Raúl Villares.

Mill concept art by Carlos Giménez.

For innocent Ofelia, the harsh reality of her stepfather’s mill is its own living nightmare.

Lala Huete and her department meticulously fabricated and tailored virtually all the period costumes. In del Toro’s production philosophy, “If you have bad wardrobe, you have a bad movie; if you have bad production design, you have bad wardrobe. For me, wardrobe and production design are a single department.”

The costume design subtly blended into the world of the film, right down to the color of the early Franco-era military police uniforms. “Their uniform is historically accurate except it is not the correct color of blue—Lala and I very carefully varied the shade of blue in the pantone scale until we found one that was in harmony with the color palette of the movie,” del Toro explains. (In addition to the military police, Vidal’s forces included the civil guards, who wore green uniforms.)

Some of the costumes evoked the story’s fairy-tale roots—a green-and-white dress that Ofelia wears on her first task evokes the dress shown in the classic illustrations of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, while in a magical final scene Ofelia is wearing red shoes that recall the ruby slippers Dorothy wore in Oz. A green nightgown that Ofelia wears when she enters the lair of the sinister Pale Man was an “iconic piece of wardrobe” for the director.

“I wanted the wardrobe to tell you things about the characters,” del Toro adds. “The shiny shoes that Ofelia’s mother buys her are precious little things that tell you how the mother views the child. The Captain had to have incredibly tight boots and gloves, sort of like he is being held together, and Lala tailored that uniform to perfection. Mercedes has this beautiful woolen shawl on her shoulders that is period accurate but also gives the motherly warmth she feels toward Ofelia, whereas the mother is kept in colder tones—one of the tricks was I wanted Mercedes to look more like the mother of Ofelia than Carmen does, and the wardrobe supports that.”

Before filming, there were the usual rehearsals and personal preparations for the actors. As leader of the military forces, López was coached on thinking and acting like a soldier, from how to ride a horse to making a proper military salute (not too high, not too low, “right at the button on the hat,” the actor notes). López’s character would be self-absorbed and self-conscious about his appearance; always well groomed and impeccably turned out in uniform.

Vidal and his command and household staff await the arrival of the captain’s pregnant wife, their costumes meticulously designed by Lala Huete.

Ofelia, wearing her “Alice”-style dress, prepares to face her first fantastical task.

Del Toro drew a stark contrast between the maternal influences on Ofelia: Carmen wants her child to abandon fairytale dreams and grow up; Mercedes is protective and provides unconditional love.

“We rehearsed off-camera quite a lot with Guillermo, as he wanted to make sure everything worked and made sense,” Baquero adds. “He was very meticulous and specific in every scene with what he needed and wanted us to do, so rehearsals were vital in the process. And working with such first-class cast members was a very positive experience for me. They were all extremely sweet and generous with me. Even after all these years, I still keep in touch with a couple of them.”

Del Toro had specific insights as to how each actor could bring their respective characters to life. For Mercedes, he wanted Maribel Verdú to keep her character’s physical motions to a minimum, to not gesticulate with her hands. “I don’t move my hands unless, of course, I’m cooking, or I need to kill Sergi,” she says with a laugh, referencing their character’s dramatic confrontation later in the story. “Otherwise my hands are at my waist. Everything Guillermo asked of us was concrete. For example, Mercedes always stands very straight and when she talks to you, she doesn’t lean in. Everybody does that—when you talk to someone you lean in, to give them importance. But she refuses to bend.”

Before filming, del Toro had a special assignment for film composer Javier Navarrete involving Verdú’s character. Although traditionally composers write and record music in concert with the imagery of the final film, del Toro wanted a lullaby for Mercedes to hum to Ofelia during a key scene in the shoot. “And, quite naturally, most of the score came from that song, that lullaby,” Navarrete notes. “This melody became the main theme of the movie.”

“The only easy time I ever had on Pan’s Labyrinth was with the music; it was one of the easiest scores I ever had,” del Toro recalls. “When we found the lullaby I found the movie’s heart. I had the lullaby with me on my Walkman or iPod and I would listen to it during the shoot and be moved to tears. I would truly be charged! It was sort of an amulet that kept me going.”

Navarrete, who had first worked with del Toro on The Devil’s Backbone, felt there was a huge contrast in their working relationship on this new film, a spirit of confidence in themselves and each other. “I quite liked the first movie, but it was more, ‘Let’s see what happens,’” he muses. “His briefing for Pan’s Labyrinth was very clear. He wanted a melodic score that everybody could understand. He said, ‘Don’t write for your friends. Write for the taxi driver, the man of the street, for everyone. And please make a melodic score.’ He was very clear about this.”

The composer characterized the music for the Faun as not melodic but atmospheric, with “harmonic progressions” linked to that mystical character. “Captain Vidal doesn’t have a melody, although there’s like a military drum, little touches here and there to illustrate the action,” Navarrete explains. “But the girl has a melody, a theme, as do the guerrillas in the forest who represent a kind of light in a dark story. They represent hope in the real-life world.”

The Faun himself (often called “Pan” by the production, although it is not the Pan of mythology), was one of DDT’s major challenges. But as with DDT’s other work on the film, including a giant toad residing in a dead fig tree and the child-eating Pale Man, del Toro wanted his special effects department to avoid the typical movie monster look. “Let’s put it this way, if an American company did Pan or the Pale Man they wouldn’t look like superheroes, but they would be more beautiful than they are in the movie,” David Martí muses. “Pan would have more muscles, that kind of thing. It’s a more European look for the monsters. They couldn’t look slimy and disgusting, but they had to be iconic and scary.”

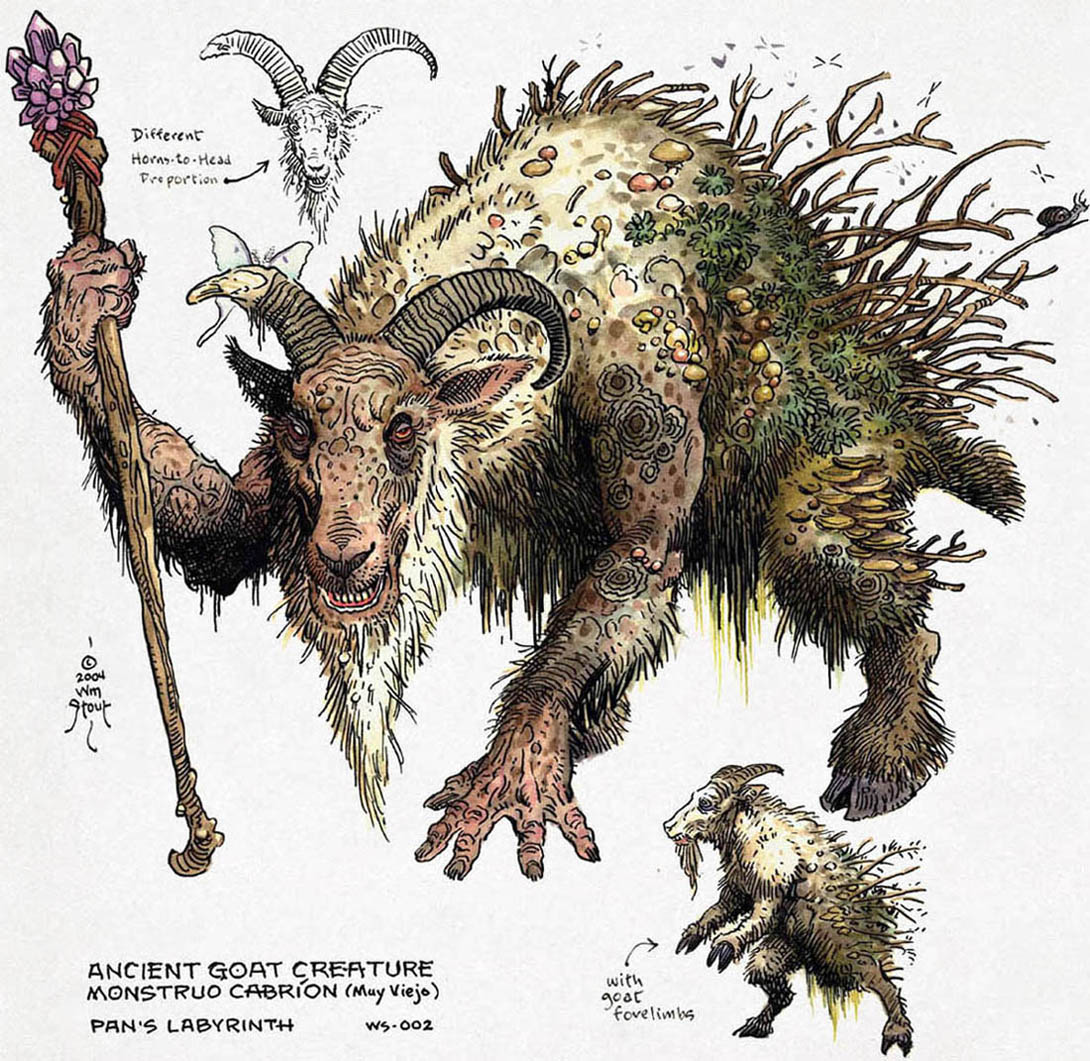

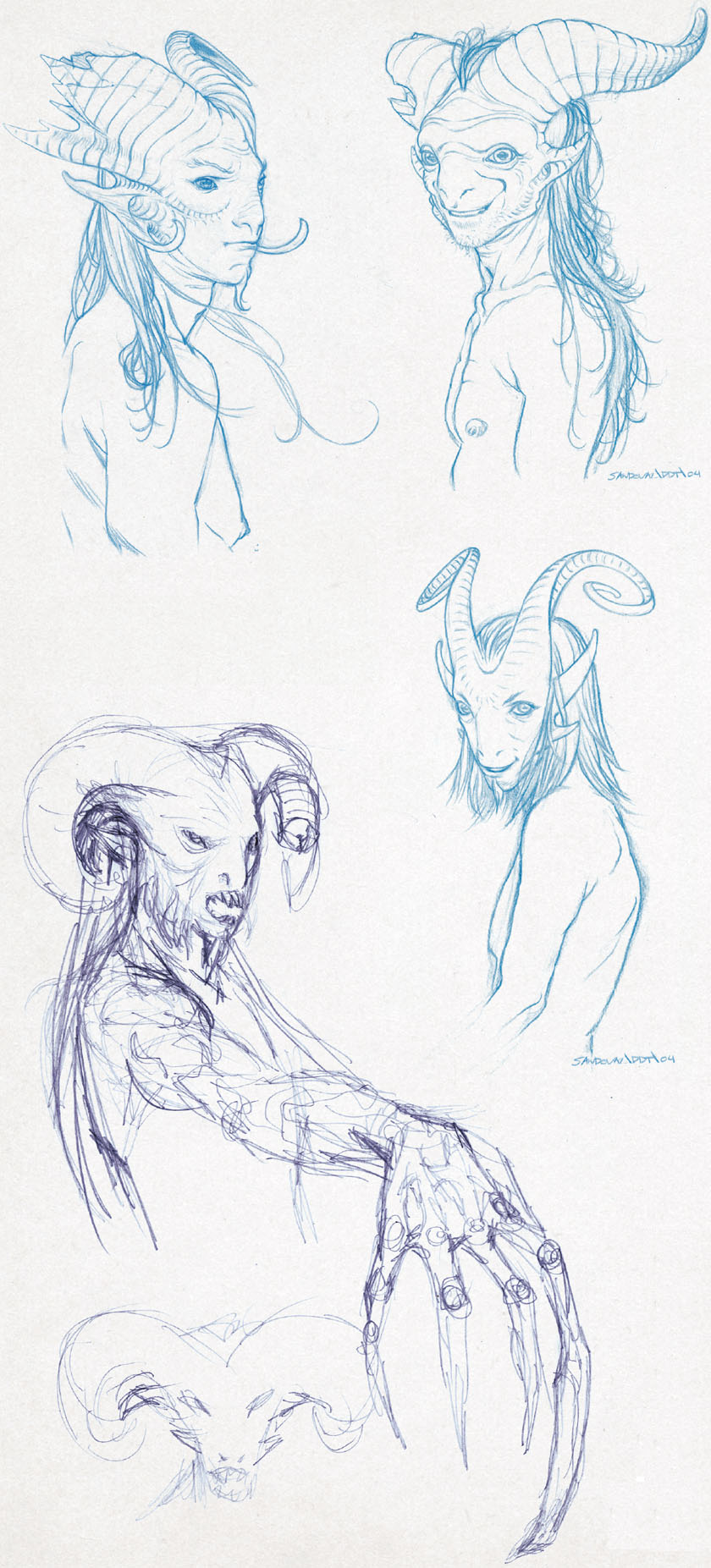

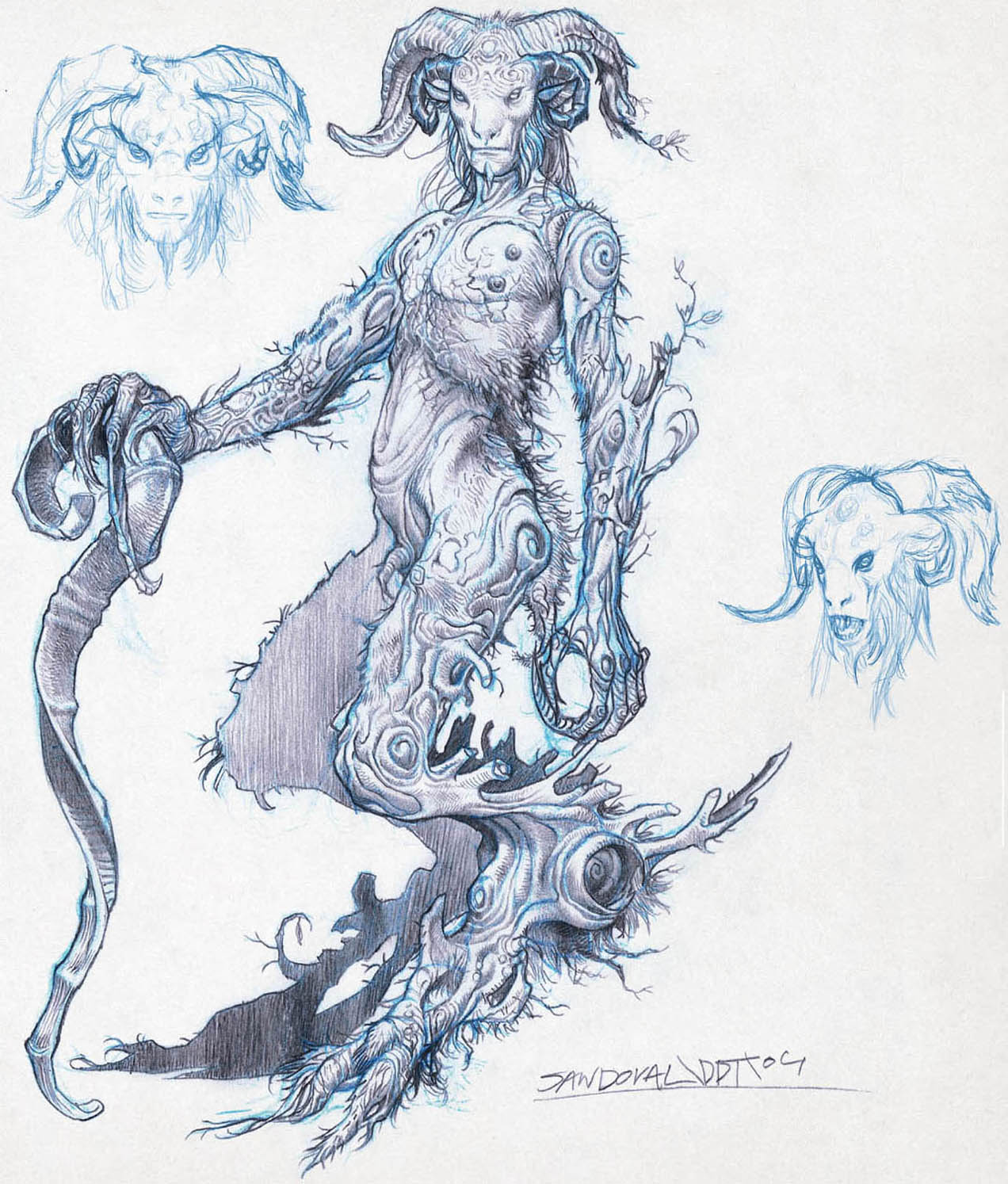

Martí recalls the first Faun design they saw was a “cute” image of a fat old goat man by legendary American artist William Stout. Another early idea imagined the Faun as a much younger character. The next version of the script described an adult with goat legs, and conceptual artist Sergio Sandoval provided several illustrations that brought this idea to life. “Guillermo was very obsessed with the idea that this guy has to come from the woods and we had to give him an animal look,” Martí recalls. “We started making a design where the legs had roots, and he loved that idea. He said, ‘Let’s put tree stuff on the whole body.’ And that is how we created Pan.”

Early William Stout “ancient goat creature” design.

The process of creating the Faun began with life casting—creating a physical three-dimensional copy of parts of a living person by applying liquid material and casting it. Lifecasts allow creature effects artists to style and create character pieces modeled to an actor’s body—the Faun’s head, for example, was sculpted over a life-cast taken of Doug Jones’s own head. But because Jones wasn’t going to be available until April 2005, DDT began with earlier lifecast pieces taken of the actor for Hellboy. “We started with some [lifecast] pieces that our good friend from Spectral Motion, Mike Elizalde [creature/makeup effects supervisor on Hellboy], sent us,” David Martí explains. “Later, when we had Doug, we molded him completely—even his teeth. We did it in two halves, the legs, and then the torso and arms. But the process is always hard and we prepared everything [so it could be applied] as fast as possible.”

Faun maquette by DDT that shows the whole body adorned with tree bark textures.

Faun concepts by Sergio Sandoval, including a key design that imagined the Faun’s legs as tree roots.

Doug Jones undergoes the difficult lifecasting process under the expert care of DDT’s technicians.

The complex costume included prosthetic pieces for the Faun’s legs, and, as a test, DDT prepared a rough goat leg shape out of foam to see if that worked on the actor. Jones distinguishes between a creature costume, designed specifically for an actor to wear, and makeup, which is the application of prosthetic pieces, skin coloring, and other enhancements—the Faun was “the combo platter,” he says.

The ram’s horns were heavy with battery packs and servos that allowed DDT to remotely puppeteer facial features and other details. The face was a mask with a mouth section that would move naturally when Jones spoke his dialogue, although Faun dentures covered his own teeth. There was a body suit that went on in multiple pieces, including an independent torso piece that came down and underneath his pectorals and allowed freedom of movement. The legs were separate pieces hooked to a belt; the Faun’s long hand and fingers were gloves. The bottom half included “zigzagging” shaped goat leg pieces attached to the actor’s own legs, which were wrapped in greenscreen-like material for the sake of the visual effects department. “This design had never been done before, and I conceived it to save money on VFX,” says del Toro. “If you watch carefully, in some shots you can see Doug’s real legs in the shadows on the floor—we ran out of money for VFX!”

“[CafeFX] could wipe away from the knee down and what remained was the prosthetic piece that went from the knee back, and then diagonally came underneath my green foot and a tree stumpy type of foot underneath mine, this thing built around a metal stilt,” Jones explains. “It wasn’t like a circus stilt. I was going clunk, clunk, clunk—a flat piece of metal hoof. It was more stable than it sounds, but it made me seven feet tall.”

The final Faun make-up as seen in an on-set still.

Because of the tail and goat leg configuration, during breaks Jones had to lean on a specially designed bicycle seat and T-bar setup.

“Guillermo loves practical effects and he wanted to create the Faun, Pale Man, and a giant toad and have us enhance them to feel more alive and believable,” explains Jeff Barnes. “He specifically wanted to get the performance for Pan and the Pale Man out of Doug Jones, so we did CG enhancements for that. We did subtle things to help sell the reality of all the creatures.”

It was late in preproduction that a new iteration of the script imagined the Faun as aging backward, becoming younger the closer Ofelia gets to completing her tasks and fulfilling her destiny. “I pushed [DDT] on creating three or four different stages of the Faun,” del Toro explains. “Most people don’t notice it in the movie, but it’s noticeable to me. As the movie progresses, and the Faun becomes younger and more beautiful, he also becomes less trustworthy and sinister. I thought that reversal was important at a storytelling level. The first time he appears, he’s like a bumbling old fool, he is shaking and looks almost like a jester. As he becomes younger he’s now eating raw meat and feeding it to the fairies and is a little more ambiguous. And then he looks beautiful, even as everything is going to shit around him, so he seems to be receiving nourishment from the conflict.”

Doug Jones takes a bow. The performer’s green wrapped legs would be digitally removed to provide the illusion of inhuman goat legs.

Because of the tail and goat leg configuration, during breaks Jones had to lean on a specially designed bicycle seat and T-bar setup.

“We didn’t have to do anything new; we just had to change colors or remove pieces on the suits,” Martí recalls of the aging effects. “We had two different paints on the suits. The chest, for instance, was covered with darker tree bark pieces on top. If you removed it you could see more of a light, or cream, color. In the beginning, when he is oldest, he is darker, he has white hair, the left horn is broken, and his eyes have cataracts. By the end, we had more flesh color on the face, the white hair is gone, the horns are complete, and the eyes are shiny.”

Martí’s favorite memory of the movie was the first time Doug Jones was completely made up as the Faun. The three-month shoot had already begun that summer, and they were roughly a month in when Jones showed up, as scheduled, for the duration. That first makeup session took six hours (the complex application quickly got down to four hours), and it was night when they finished. The crew was shooting at the labyrinth location and the Faun team waited until a break before making their entrance.

“When the Faun appeared, everybody got quiet,” Martí recalls. “That had never happened to us before. Usually, everybody goes, ‘Wow!’ And then Guillermo came out of the maze and he hugged Doug very hard and everybody started applauding. Even Montse and I could not stop looking at him. It was like we were hypnotized. After all the effort, the sculptor’s molds and foam latex and stuff you have done, it was like a real creature. That was magic.”

Using the lifecast of Doug Jones, the DDT team begin work on constructing the Faun costume.