I think my closest relationship as a storyteller is with the fairy tale. Everything I do has a sort of a fairy-tale patina. To me, the horror genre is very closely related to fairy tales. My movies are also very autobiographical. I am able to understand the bad guys and good guys and all the characters. . . . When I was a child I was not very outgoing; I was basically mute. I would not talk to anyone, I would observe a lot. You see that type of child in my movies. —GUILLERMO DEL TORO

THE LITTLE BOY FEARFULLY AWAITED the church clock tower’s tolling of midnight, knowing that at the stroke of that hour he would see the hand of a mythical faun appear from behind its hiding place. The face would follow, then a goat’s leg—and he would start screaming.

That little boy was filmmaker Guillermo del Toro, in the grip of what he recalls as his childhood penchant for “lucid dreaming.” Did his apparition foreshadow the Faun of Pan’s Labyrinth, the film that has been called his masterpiece? “Well, I don’t know,” del Toro muses. “It was like a goat man and far more malevolent and demonic than the one in the movie. I would see it and always wake up screaming. There are all those images in Mexican iconography of the devil being sort of an upright goat, a goat man. I suppose it had more to do with that. I think a lot of the iconography in Mexico, of the Catholic religion, is very gory and sinister, with notions of sin and damnation and good and evil and sacrifice and suffering—all of that has stayed with me my whole life!”

Del Toro has retained childhood memories rich in nightmarish visions and wonder. That child within has been a voice in not only Pan’s Labyrinth but throughout his work—del Toro has said his movies are all really one long autobiographical movie. “As adults, we lose the child we were, you know?” reflects Mexican film producer Bertha Navarro, who has worked with del Toro since his career began. “But Guillermo has that child within himself, and that is what is amazing about him. I think that is a very powerful and unique way of seeing things.”

Del Toro is popularly known for his Hollywood blockbusters, including the Hellboy movies, but fans, friends, and fellow filmmakers have a special fondness for his three lower-budget Spanish language films—his directorial debut, Cronos (1993), The Devil’s Backbone (2001), and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006). Navarro, who produced all three, notes they are bound by unifying themes: “Guillermo has his personality in all his films, but these three films are closer to him in a cultural and historical way, and they all [feature] a child or children.”

The parallels between del Toro’s own childhood and the imaginary worlds of his films are clear. A completely mute girl witnesses her grandfather’s transformation into a vampire in Cronos, a clear reflection of his younger tongue-tied self. His childhood memories haunt the ghost story at the heart of The Devil’s Backbone—a corridor where an apparition of a boy is glimpsed is a re-creation of a corridor in his grandmother’s house. And in Pan’s Labyrinth, a young child encounters the monstrous stuff of young del Toro’s nightmares.

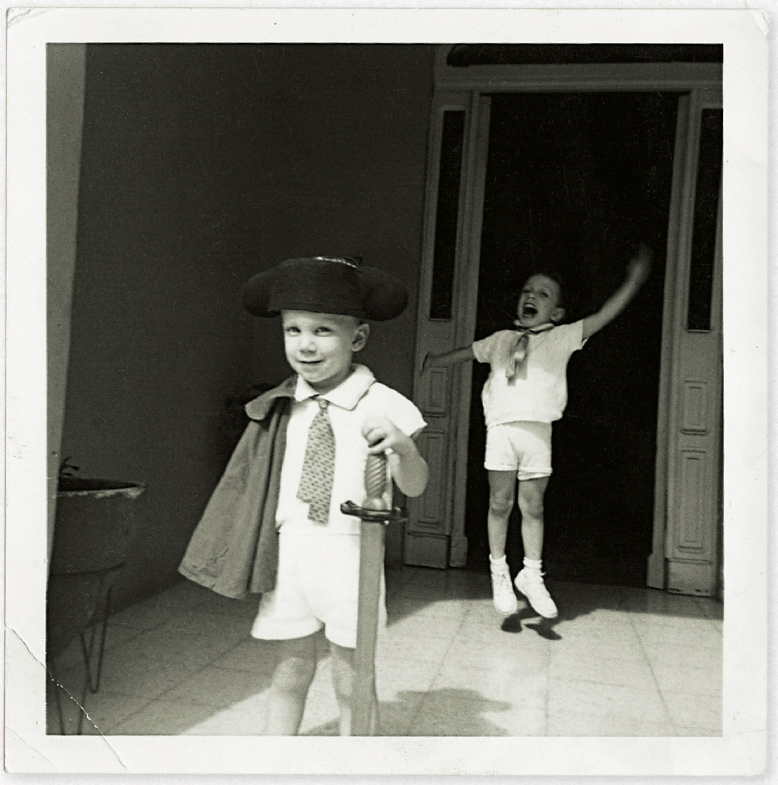

The young Guillermo del Toro (foreground) with his brother, Federico.

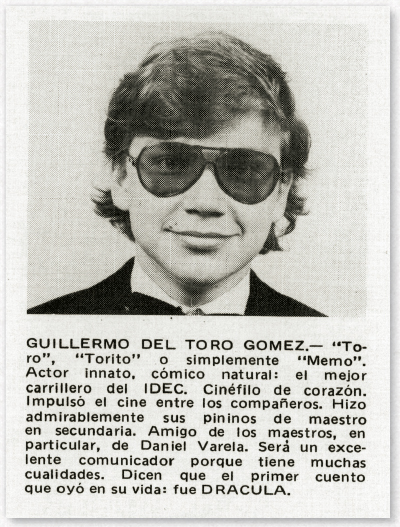

A clipping from del Toro’s 1982 school yearbook reads: GUILLERMO DEL TORO— “Toro,” “Torito,” or simply “Memo.” Innate actor and natural comic: the best prankster at IDEC. Cinephile at heart. Impelled his friends to visit the movie theater. Friend of teachers, in particular Daniel Varela. Will be an excellent communicator because he has so many great qualities. They say that the first story he heard in his life was Dracula.

“We are fascinated by horror—but I find that very healthy,” del Toro reflects, adding that embracing the “otherness” is the ultimate act of tolerance. “Being in love with the monstrous is about the desire to understand the Other, as opposed to destroying it. War is the ultimate act of intolerance; there are only live victims and dead victims.” That unique blend of heart and horror characterizes his work, from Blade II (2002), Hellboy (2004), and Hellboy II: The Golden Army (2008), to the sci-fi epic Pacific Rim (2013) and his Gothic romance, Crimson Peak (2015).

But it is The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth that are the most closely linked in theme and spirit—the writer/director himself has likened his reiteration of familiar motifs to an artist returning to paint the same tree again and again but creating each piece anew with fresh eyes. Del Toro’s long-time cinematographer, Guillermo Navarro, brother of producer Bertha Navarro, says that the seeds for Pan’s Labyrinth were indeed planted in the soil of The Devil’s Backbone. Both explore the monstrous and the supernatural; both are told against the backdrop of the ultimate horror of war; both were shot in Spain and co-financed by Spanish investors.

In Pan’s Labyrinth, the Faun has an air of menace, as seen in this 2015 image by William Stout.

The director and his stars command the red carpet at the premiere of Pan’s Labyrinth during the 59th International Cannes Film Festival, May 27, 2006.

Cannes photo courtesy of EdStock/istockphoto.com. Photo by Peter Kramer.

The Devil’s Backbone is set in 1939, the final year of the Spanish Civil War, in an orphanage on a sunburned plain far from the fighting. The institution is run by an older couple loyal to the Republican forces fighting the Fascists—and rumor has it they have a cache of gold to help finance the cause. A fixture of the grounds is the bomb that once dropped from the sky but never exploded—it marks the orphanage as a place of secrets. The legend of the gold beguiles the cruel young groundskeeper who has grown up within its walls, while a new orphan is drawn into the mystery of a phantom boy he sees in clear daylight his first day, an apparition holding the most sinister secret of all.

“Originally, my idea was just to do Devil’s Backbone,” del Toro explains. “But the more I learned about the Civil War, the more I found it was almost like an onion—the more layers you peel, the more you cry. It was tragedy upon tragedy. The Republican side and the Fascist side both committed enormous atrocities and both had enormous losses. It was really hard for me to articulate that only in one movie, but I felt very proud of Devil’s Backbone.”

When del Toro was working on Cronos, ideas for the film that became Pan’s Labyrinth were already gestating and taking form through drawings and story ideas recorded in the notebooks integral to his creative process (the film’s brutal interrogation scene was imagined all the way back in 1993). Prior to its worldwide release in November of 2001, The Devil’s Backbone began its theatrical release in Spain on April 20, followed by film festivals screenings that included the Telluride Film Festival on September 2. On September 11—the day that terrorist attacks on US soil led to the destruction of New York’s World Trade Center—the film opened at the Toronto International Film Festival. In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, del Toro felt compelled to continue exploring the themes begun in The Devil’s Backbone, imagining the follow-up as the second part of a thematic trilogy. “When 9/11 happened, I felt a lot of emotion about innocence and war,” he recalls. “Pan’s Labyrinth is not an allegory of 9/11. It’s just my response to my emotions.”

There was symmetry to the release of Pan’s Labyrinth in 2006, five years after The Devil’s Backbone—the stories themselves are set five years apart. In the second film in del Toro’s imagined trilogy, it is 1944 and General Francisco Franco’s Fascist government is in control of neutral Spain. An innocent girl named Ofelia, who always has her nose buried in a book and a mind full of wonder, is confronted with harsh reality at a mill in a forested region that has been commandeered in the government’s ongoing war against Republican holdouts. Ofelia and her pregnant mother, Carmen, are introduced being driven in an elegant Rolls Royce to join Carmen’s new husband, Captain Vidal, the officer in charge of exterminating the local guerrillas. During a stop, Ofelia wanders away and finds a curious object on the ground—the right eye of a stone figure partially concealed by forest growth. She pops it back in place and a winged stick bug crawls out of the statue’s gaping mouth. On that first day at the old mill, the stick bug reappears and she follows it to an ancient labyrinth nearby. That night, the stick bug again visits Ofelia, transforms into a fairy, and leads her deep into the labyrinth. There she meets an old Faun who welcomes her as the lost Princess Moanna—the daughter of the king of the underworld! But before she can reclaim her place in the kingdom, she must prove herself. The Faun gives her the Book of Crossroads that will, in turn, instruct her on three tasks she must successfully complete before the full moon.

El Laberinto del Fauno, the film’s original Spanish title, was pure del Toro: an unlikely blend of genres—fairy tale, horror story, and wartime period piece, with an innocent girl at its center. The film—helmed by Mexican filmmakers, co-financed with Spanish investors, and made in Spain—was a low-budget production. In fact, Pan’s entire budget—del Toro places it at $19 million dollars—roughly amounted to the visual effects costs alone for his previous studio film, Hellboy.

The film’s postproduction was a whirlwind rush to make its scheduled premiere at the Cannes Film Festival 2006. What no one expected was the standing ovation at the end of the screening that went on, and on, and on. . . .

“I can tell you, officially, that the director of the Cannes Film Festival said the ovation clocked at twenty-four minutes and is perhaps the longest ovation ever at Cannes,” del Toro reports. “It was, and is, the happiest day of my professional life.”

“We finished just in time for Cannes; we were stressing to get it there,” producer Bertha Navarro recalls. “Cannes is not easy, but the response of the audience was incredible. It was then that I knew the film would work.”

Cannes began an astounding ride of international box-office success that included Pan’s Labyrinth becoming the highest-grossing Spanish language film ever in the United States. Critical acclaim included Film of the Year accolades, and award ceremonies honoring all aspects of the film from the Goya in Spain, to the Ariel in Mexico, and the Academy Awards in Hollywood. The film’s unlikely triumph was a testament to del Toro’s vision and relentless drive, as well as the filmmaking culture of Mexico that made up in ingenuity and collaborative spirit what it once lacked in technical resources.

![]()

As a boy, Guillermo del Toro was always attracted to the macabre, and he found a fount of inspiration in popular culture. One of his earliest discoveries was Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, published by Forrest Ackerman. At age seven, he bought his first book, an Ackerman-edited anthology, Best Horror Stories. Del Toro was a voracious and eclectic reader, from medical books to horror comics to literature, particularly the darker realms explored by the likes of Baudelaire, Poe, and Lovecraft. He was fascinated by art and studied painters like Goya, Manet, and Picasso, along with comic book greats such as Kirby, Wrightson, and Toth. He began drawing—special obsessions included the Creature from the Black Lagoon, Frankenstein’s monster, and Lon Chaney’s ghoulish Phantom of the Opera—as well as sculpting. “My brother and I would do full human figures with clay and Plasticine—liver, intestines, the heart—fill them with ketchup, and throw them from the roof,” del Toro recalls. “So I was an artistic, but very morbid kid.”1

In the 1980s, del Toro began his career with short horror films. Makeup effects are essential to that genre but were lacking in the Mexican films of del Toro’s youth. “If you watched a Mexican horror movie from the fifties or sixties, it actually looks like a Universal monster movie in the thirties and forties, so they were very antiquated, most of the time,” del Toro says. “But they were a big influence on me in other ways. They were not afraid of mixing genres, such as a cowboy movie with a horror movie. I probably inherited the license to do that stream-of-consciousness approach to genre from Mexican cinema, the freedom where I can mix a Civil War movie with a fairy tale, you know?”

Del Toro began creating makeup for his own movies, and his friends’ films, as well. When writing the screenplay for Cronos, he realized his vampire protagonist required makeup that no one in Mexico, including himself, was technically sophisticated enough to make. The indomitable spirit and drive that would characterize his emerging career asserted itself—del Toro decided to organize his own makeup company, Necropia, and advance his abilities by studying under the master, Dick Smith, an Oscar-winning makeup artist of legendary proportions whose work includes The Exorcist, Little Big Man, The Godfather, and Taxi Driver. Del Toro wrote to Smith, who accepted him as a student.

“Guillermo went to New York and studied under Dick Smith,” Bertha Navarro says. She pauses and smiles at the wonderful audacity of it all. “Incredible.”

“It was not in a formal classroom; it was more a course of training you had to implement yourself, and that gave me a lot of discipline,” del Toro recalls, noting that J. J. Abrams was one of his fellow “classmates.” “To me, [Dick Smith] became a fatherly figure. I think that without Dick Smith I wouldn’t be a filmmaker because he was instrumental in making the tools available to me that I needed to create Cronos.”

As in his films, synchronous and synergistic connections determined the course of del Toro’s own story. He knew cinematographer Guillermo Navarro, who was working on Cabeza de Vaca—the eventual 1991 release by director Nicolás Echevarría—about the Spanish conquistador who made an epic journey across what is today the American Southwest. Navarro’s sister, Bertha, was executive producer, and the cinematographer knew she was looking for a makeup artist to create the look of the indigenous peoples. He introduced her to del Toro, who was hired—his makeup on Cabeza de Vaca became part of his thesis work for Dick Smith.

After completing Cabeza de Vaca, del Toro asked Bertha Navarro if she would read his Cronos screenplay. “I was impressed by the quality of the writing, the story—everything,” she says. “I thought, ‘Wow! This guy is so young, but so mature.’ I didn’t expect such quality from a young guy from Guadalajara. I said to him, ‘Yes! I would love to do it.’”

Guillermo Navarro also signed on as director of photography for Cronos, the beginning of a long collaboration that would include Pan’s Labyrinth. Cronos was an auspicious beginning, a highlight being its screening at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Mercedes-Benz Award.

But making Cronos wasn’t easy, Bertha Navarro recalls: “In Mexico everybody said, ‘We can’t do fantasy-horror or genre films.’ So we had trouble getting the financing. I was told that I was crazy, this young guy nobody knows [who] wanted Federico Luppi, a great Argentinian actor, [to star] and then he wants Ron Perlman, and here you are bringing all this together—you are mad! It took me maybe a year to get the financing. Also, at this time there was this change of technology, where . . . music and sound [became digital]. We didn’t have the structure yet [in Mexico], so we came to Los Angeles to do postproduction, so that was more expensive. But Guillermo did a beautiful job and it was a great film.”

The drive and determination it took to finish Cronos was an early indicator that del Toro, and the team of collaborators he was drawing into his creative orbit, had the capacity to make the most audacious dreams come true. Del Toro was part of a breakthrough generation of Mexican filmmakers, which includes his friends and fellow directors Alejandro Gonzáles Iñárritu and Alfonso Cuarón. Pan’s Labyrinth broke the “curse” that had prevented previous Mexican films from winning multiple Oscars by netting three of them. Less than a decade later, Iñárritu’s 2014 film Birdman won Academy Awards for best picture, director, and original screenplay, with his Mexican director of photography, Emmanuel Lubezki, winning for cinematography. The director’s follow-up, The Revenant, won three Oscars at the 2016 ceremony (best actor for Leonardo DiCaprio, best director for Iñárritu, and best cinematography for Lubezki) making Iñárritu only the third director to ever be so honored two years running, while Lubezki was the first to win the cinematography category three years in a row, the first being for Alfonso Cuarón’s 2013 release Gravity. Cuarón himself won Oscars for Gravity for directing and editing, the latter shared with Mark Sanger.

The young Guillermo del Toro at the top of the Empire State Building, New York City, where del Toro met Oscar-winning makeup legend Dick Smith, was a pivotal stop on his journey to becoming a filmmaker.

“With Guillermo we discuss everything we work on, absolutely everything,” Cuarón explains. “Guillermo and Alejandro are the main [collaborators] at every step of my game, from the first draft of a screenplay. It is not different with any project. And when I received my Oscar I thanked Guillermo and Alejandro.”

Del Toro’s network of filmdom friends who mutually share works-in-progress includes director James Cameron, whose filmography includes two of the most successful movies ever, Titanic and Avatar. Cameron observes that del Toro has a personal code of honor and a strong sense of morality that allows him to look “horror and the dark things square in the eye. There’s too much shifting sand underneath most people in Hollywood, and I never wanted to comport myself that way. I’ve always believed my word is my bond, and he and I bonded over that.

“One of the things that struck me, early on, with Guillermo was that he came out of a culture of young filmmakers in Mexico where everybody supported one another,” Cameron adds. “He always said that when somebody was finishing a film it was like a baby being born. You’re going through labor and everybody gathers to support, from offering advice to getting into the cutting room, and I got infected by that vision. Generally, it’s like wolves in competition, but Guillermo gave me a very different perspective of this kind of supportive network among filmmakers. I have always made myself available to him when he’s requested that I look at cuts and give comments. A couple of times when I’ve been finishing a film he’s taken it as a kind of moral duty to come and camp out with me. It’s pretty amazing, such a high-caliber filmmaker freely offering that.”

As part of del Toro’s collaborative circle, Cameron was among those with a front-row seat as Pan’s Labyrinth emerged, first as a tale del Toro told, then as a screenplay, and on to early cuts and pre-theatrical-release screenings. “There was something about the filmmaking in Pan’s Labyrinth that represented a maturity or confidence,” Cameron reflects. “That movie just felt different to me from Guillermo’s other work—it felt like something he had been building toward.”

Producer Thomas Tull, founder and CEO of the production company Legendary, who was inspired to collaborate with del Toro after seeing one of those pre-release screenings of Pan’s Labyrinth, explains that his privileged position has allowed him to peek behind the curtain at the creative process of many great filmmakers. He has pored over del Toro’s famous notebooks and uses the phrase “mad genius” to describe the filmmaker himself.

“I’ve said to him, ‘The line between insanity and genius is often very thin,’” Tull recalls. “When you look at Guillermo’s notebooks, you start to connect the dots a little bit on how he thinks. It’s not just little drawings or ideas. It’s a peek into the logic jumps he makes, the way he plots. You realize that an idea he’s developing might be as extraordinary as what he has in his head—sometimes it’s even more so.”

After Cronos, del Toro made his first Hollywood film—a breakthrough, baptism of fire, and crossroads experience rolled into one—embarked on that first filmmaking sojourn to Spain for The Devil’s Backbone, and returned to the United States in triumph to direct two big Hollywood studio productions. All the while, the elements of Pan’s Labyrinth were growing, coalescing, and transmuting until coming to full bloom in the summer of 2005 in Spain, when filming began at location sets and soundstage spaces.

The Pan’s Labyrinth theatrical release poster features the fig tree that is the setting for the first test for the young heroine, Ofelia, who must prove she is the mythical lost princess of the kingdom of the underworld.

Looking back over the ten years since the release of Pan’s Labyrinth, Bertha Navarro recalls the mix of young talent and time-tested collaborators who somehow accomplished the most audacious filmmaking feat of all—creating a masterpiece. “Pan’s Labyrinth was a very creative moment,” Navarro reflects. “Also, it was beautiful to work again with my brother; I did all three [Spanish-language] films with him. It was like creating a team. You work together and even without talking you understand each other. Pan’s Labyrinth was very hard to do. But, fortunately, you forget the hard times; you keep only the good part.”

Ultimately, del Toro feels that making a movie is about controlling the chaos that always conspires against one’s creative dreams. It might be a set that wasn’t measured properly and is found to not be ready for filming; environmental conditions that conspire against the best-laid plans; an actor who must leave for a prior commitment with a key scene still to shoot. Whatever the challenge, it is up to the director to adjust and find a way to keep a production moving forward. This is true of any ambitious production, but Pan’s Labyrinth would particularly test del Toro’s ambitions and the mettle of his team.

“I want to tell you that Pan’s Labyrinth was the worst experience of any movie I have done,” says David Martí, the co-partner with Montse Ribé of Barcelona-based DDT Efectos Especiales, the special effects studio that created memorable creatures for the film, including the Faun and the sinister Pale Man. “Very good movie; very bad experience. We went bankrupt. I cried three times. I got into an argument with Guillermo, the only one in my career for the now eleven years that I’ve known him. If I have to do another Pan’s Labyrinth I will die! I will get a heart attack or something.” But DDT retains lessons learned from the creative struggles. Martí adds: “We have a saying: ‘We always have the ghost of Pan’s Labyrinth behind us.’”

The ghost of Pan’s Labyrinth remains with the Mexican, Spanish, and American members of the production. Del Toro himself has not forgotten the struggles of making El Laberinto del Fauno. “I am not able to forget the problems,” del Toro admits with a pained laugh. “The two hardest shoots I’ve had at almost every level were Mimic and Pan’s Labyrinth.”

Mimic, del Toro’s first Hollywood movie, released in 1997, was a hardball lesson in studio politics and an early turning point. But of the two examples, Pan’s Labyrinth remains del Toro’s toughest production. He not only directed but also wrote the story and screenplay and was “down in the trenches,” as he puts it, as a producer. “I was in a state of constant anxiety because almost anything that could go wrong, went wrong,” del Toro recalls. “I was sleeping three hours a night and losing three pounds a week. I was dealing with very [mundane] stuff like getting immigration permits and passports for the technicians coming to Spain from Mexico, and dealing with a [tight] budget with the line producer. At the same time, I was dealing with huge creative challenges—I hired a [relatively inexperienced] production designer, I was pushing [DDT], a very small makeup effects company, to the limit, I was dealing with the overages of visual effects and how to make the movie fit the very narrow budget we had for the ambition we had. And most of the crew thought we were making a strange, silly movie. We had huge pressures.”

Del Toro also had to face “the enmity” of an outside group of Spanish movie producers who were looking for any pretext for shutting it down, not to mention drought and fire conditions at the main location that resulted in restrictions imposed by the Spanish government agency charged with managing the country’s forests. Throughout the adversity, del Toro relentlessly pushed his crew, as he admits: “I remained perpetually unsatisfied and hungry. No matter what we did, I wanted more.”